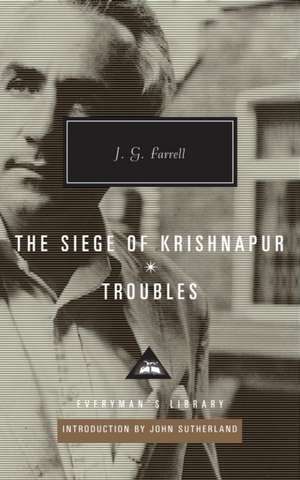

The Siege of Krishnapur, Troubles: The Golden Compass, the Subtle Knife, the Amber Spyglass: Everyman's Library

Autor J. G. Farrell Introducere de John Sutherlanden Limba Engleză Hardback – 29 feb 2012

Inspired by historical events, The Siege of Krishnapur is the mesmerizing tale of a British outpost, under siege during the Indian Mutiny of 1857, whose residents find their smug assumptions of moral and military superiority and their rigid class barriers under fire—literally and figuratively. The hero of Troubles, having survived the battles of World War I, makes his way to Ireland in 1919, in search of his once-wealthy fiancée. What he finds is her family's enormous seaside hotel in a spectacular state of decline, overgrown and overrun by herds of cats and pigs and the few remaining guests. From this strange perch, moving from room to room as the hotel falls down around him, he witnesses the distant tottering of the Empire in the East and the rise of the violent "Troubles" in Ireland.

Din seria Everyman's Library

-

Preț: 177.11 lei

Preț: 177.11 lei -

Preț: 203.04 lei

Preț: 203.04 lei -

Preț: 159.64 lei

Preț: 159.64 lei -

Preț: 145.38 lei

Preț: 145.38 lei -

Preț: 209.00 lei

Preț: 209.00 lei -

Preț: 105.05 lei

Preț: 105.05 lei -

Preț: 170.03 lei

Preț: 170.03 lei -

Preț: 249.64 lei

Preț: 249.64 lei - 12%

Preț: 115.88 lei

Preț: 115.88 lei - 13%

Preț: 113.25 lei

Preț: 113.25 lei -

Preț: 191.59 lei

Preț: 191.59 lei -

Preț: 217.58 lei

Preț: 217.58 lei -

Preț: 142.91 lei

Preț: 142.91 lei -

Preț: 145.58 lei

Preț: 145.58 lei -

Preț: 120.46 lei

Preț: 120.46 lei -

Preț: 196.43 lei

Preț: 196.43 lei -

Preț: 140.04 lei

Preț: 140.04 lei -

Preț: 200.60 lei

Preț: 200.60 lei -

Preț: 95.27 lei

Preț: 95.27 lei -

Preț: 200.85 lei

Preț: 200.85 lei -

Preț: 124.77 lei

Preț: 124.77 lei

Preț: 187.62 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 281

Preț estimativ în valută:

35.90€ • 37.48$ • 29.71£

35.90€ • 37.48$ • 29.71£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307957849

ISBN-10: 0307957845

Pagini: 728

Dimensiuni: 134 x 206 x 39 mm

Greutate: 0.74 kg

Editura: Everyman's Library

Seria Everyman's Library

ISBN-10: 0307957845

Pagini: 728

Dimensiuni: 134 x 206 x 39 mm

Greutate: 0.74 kg

Editura: Everyman's Library

Seria Everyman's Library

Notă biografică

J. G. FARRELL (1935-1979) was an Anglo-Irish novelist who grew up in England and Ireland. At the age of forty-four he was hit by a wave while fishing on the Irish coast and was washed out to sea.

JOHN SUTHERLAND is the author of seventeen books on literature and language, a regular columnist for The Guardian, and an emeritus professor at University College, London.

Introduction by John Sutherland

JOHN SUTHERLAND is the author of seventeen books on literature and language, a regular columnist for The Guardian, and an emeritus professor at University College, London.

Introduction by John Sutherland

Extras

From the Introduction

Late in his career, in conversation with his friend Paul Barker, Farrell confided that ‘the really interesting thing that’s happened during my lifetime has been the decline of the British Empire’. The choice of epithet is tellingly unfeeling. He did not lament or rejoice in that decline. Why not? Because when things break down you see more clearly how they work. That ‘interested’ him. Unlike most other imperial powers, Britain had given up its colonial possessions without too much bloody struggle and, to be honest, something resembling relief. But for every empire in its terminal phase there is always one colonial possession which cannot, under any circumstances, be let go of. In France, as Farrell had witnessed in the 1960s, it was Algérie Française ߝ that chunk of North Africa bizarrely designated an outlying region of ‘metropolitan France’. In England it was ‘John Bull’s Other Island’. Albion could no more part with the six counties than it could carve off Cornwall and give it to Jersey.

As the 1960s ended Farrell was mature enough to handle such big themes. He was thirty-five years old, nel mezzo del cammin, in Dante’s description. He was impatient to do something worthy of his new sense of what his fiction should be. ‘When I look in the mirror,’ he wrote in a notebook, ‘I notice that I’m growing old and still haven’t done anything good. I remind myself of the main character in Chekhov’s masterly ‘‘A Dull Story’’.’ Propelled by amphetamines and a dynamic new agent, he wrote Troubles. Whatever else, it would not be a dull story.

Novelists, like generals, need luck. Farrell’s chronicle of the aftermath of the 1916 Irish uprising, came out in 1970, a few months after Ulster had exploded once more into flames. Few novels have been more timely. The more so since, as Farrell always insisted, Troubles was as much about the present as the past. The novel was generally applauded for its topicality but caused much perplexity as to its tone. British soldiers and British citizens were dying. Why, it was asked, was Mr Farrell not entirely serious about this surely serious issue. The oddly comic approach ߝ a cross between Evelyn Waugh and P. G. Wodehouse as one critic neatly put it ߝ is very much an acquired taste. British readers had not yet acquired it and would not fully do so until the Irish flames died down a bit.

Troubles is set in 1919ߝ21. The hero of the novel, so to call him, is an English ex-Major (still addressed by that now honorary title) who, if not a military hero, did his duty in the trenches. What the Great War was all about he was never quite sure. Shell-shock has, in the medical description of the time, rendered him ‘neurasthenic’ ߝ chronically passive. Farrell had been impressed, a couple of years before, by reading The Man Without Qualities. Musil’s use of his passive hero, Ulrich, as a reflecting surface rather than an agent had struck him as a technique to copy.

As the novel opens Major Brendan Archer has come to Kilnalough, on the south-eastern coast of Ireland, to claim his bride. He has not rushed to do so. Months-long medical treatment for a post-war nervous breakdown has been required. Nor is he is entirely sure that he is actually engaged to Angela Spencer. There was a brief encounter, on leave in 1916, in Brighton. Did he propose? Did she accept? He has no distinct memory ߝ although her letters to him during his time in the trenches make it clear that she regards him as her fiancé.

Angela, once a belle, now an invalid (dying, although Archer does not know it), lives in a hotel, the Majestic, owned and managed by her father Edward ߝ a fanatic Unionist, and ‘ex-India’. The Majestic is majestic no longer. The statue of Queen Victoria on horseback at its entrance is stained green (ominous colour) by time and fungus. During the climactic siege by the Sinn Feiners it will be violated by gelignite ߝ incompetently, alas, leaving the monarch still mounted but obscenely skirtless. The hotel’s fabric is in a condition of advanced decomposition. Its only residents are a crew of genteel old ladies no longer capable of paying their bills but with nowhere else to go. A comic moment of the hotel’s inexorable crumble conveys the distinctive tang of Farrell’s narrative:

One unseasonably warm day the giant m of majestic detached itself from the façade of the building and fell four storeys to demolish a small table at which a very old and very deaf lady, an early arrival for Christmas, had decided to take tea in the mild sunshine that was almost like summer. She had looked away for a moment, she explained to Edward in a very loud voice (almost shouting, in fact), trying to remember where the floral clock had been in the old days. She had maybe closed her eyes for a moment or two. When she turned back to her tea, it had gone! Smashed to pieces by this strange, seagull-shaped piece of cast iron (she luckily had not recognized it or divined where it had come from). [pp. 545ߝ6]

It would be a dull reader who did not pick up the primary allegory. It glows radioactively. Colonial Ireland itself is in terminal decay. But the allegory is spiced by Farrell’s idiosyncratic sense of the absolute absurdity of things ߝ even things which the mass of us find rather serious. One can’t help feeling sometimes he is laughing at us.

After Angela’s surprising death, Archer falls in love with a local Catholic woman much smarter than he and disinclined to do more than toy, cat-and-mouse style, with her bumbling English admirer. Spencer, meanwhile, goes certifiably mad. The civil unrest heats up to the point of rebellion. There is the de rigueur siege, but so disintegrated is the Majestic that it collapses and burns down of its own structural weakness leaving, among the ashes, a wilderness of 250 indestructible toilet pans and wash-basins.

Troubles received polite but grudging reviews. A scathing denunciation in the New Statesman, which took deep offence at his pas sérieux tone, caused Farrell some serious irritation. It was a hard novel to get hold of in the, once again, troubled early 1970s. Could one decently smile at Farrell’s Irish comedy with bombs going off in London or some poor child being blown to smithereens on the Falls Road?

It took years ߝ forty, to be precise ߝ before Troubles could be read as it should. In 2010 the Booker committee, convened to nominate the best novel of the Prize’s ‘lost year’, 1970 gave the award to Troubles. It would have been piquant for Farrell (dead thirty years) to have seen the New Statesman join, belatedly, in the chorus of acclaim, instructing its readers to take Troubles on holiday with them as their beach book.

Late in his career, in conversation with his friend Paul Barker, Farrell confided that ‘the really interesting thing that’s happened during my lifetime has been the decline of the British Empire’. The choice of epithet is tellingly unfeeling. He did not lament or rejoice in that decline. Why not? Because when things break down you see more clearly how they work. That ‘interested’ him. Unlike most other imperial powers, Britain had given up its colonial possessions without too much bloody struggle and, to be honest, something resembling relief. But for every empire in its terminal phase there is always one colonial possession which cannot, under any circumstances, be let go of. In France, as Farrell had witnessed in the 1960s, it was Algérie Française ߝ that chunk of North Africa bizarrely designated an outlying region of ‘metropolitan France’. In England it was ‘John Bull’s Other Island’. Albion could no more part with the six counties than it could carve off Cornwall and give it to Jersey.

As the 1960s ended Farrell was mature enough to handle such big themes. He was thirty-five years old, nel mezzo del cammin, in Dante’s description. He was impatient to do something worthy of his new sense of what his fiction should be. ‘When I look in the mirror,’ he wrote in a notebook, ‘I notice that I’m growing old and still haven’t done anything good. I remind myself of the main character in Chekhov’s masterly ‘‘A Dull Story’’.’ Propelled by amphetamines and a dynamic new agent, he wrote Troubles. Whatever else, it would not be a dull story.

Novelists, like generals, need luck. Farrell’s chronicle of the aftermath of the 1916 Irish uprising, came out in 1970, a few months after Ulster had exploded once more into flames. Few novels have been more timely. The more so since, as Farrell always insisted, Troubles was as much about the present as the past. The novel was generally applauded for its topicality but caused much perplexity as to its tone. British soldiers and British citizens were dying. Why, it was asked, was Mr Farrell not entirely serious about this surely serious issue. The oddly comic approach ߝ a cross between Evelyn Waugh and P. G. Wodehouse as one critic neatly put it ߝ is very much an acquired taste. British readers had not yet acquired it and would not fully do so until the Irish flames died down a bit.

Troubles is set in 1919ߝ21. The hero of the novel, so to call him, is an English ex-Major (still addressed by that now honorary title) who, if not a military hero, did his duty in the trenches. What the Great War was all about he was never quite sure. Shell-shock has, in the medical description of the time, rendered him ‘neurasthenic’ ߝ chronically passive. Farrell had been impressed, a couple of years before, by reading The Man Without Qualities. Musil’s use of his passive hero, Ulrich, as a reflecting surface rather than an agent had struck him as a technique to copy.

As the novel opens Major Brendan Archer has come to Kilnalough, on the south-eastern coast of Ireland, to claim his bride. He has not rushed to do so. Months-long medical treatment for a post-war nervous breakdown has been required. Nor is he is entirely sure that he is actually engaged to Angela Spencer. There was a brief encounter, on leave in 1916, in Brighton. Did he propose? Did she accept? He has no distinct memory ߝ although her letters to him during his time in the trenches make it clear that she regards him as her fiancé.

Angela, once a belle, now an invalid (dying, although Archer does not know it), lives in a hotel, the Majestic, owned and managed by her father Edward ߝ a fanatic Unionist, and ‘ex-India’. The Majestic is majestic no longer. The statue of Queen Victoria on horseback at its entrance is stained green (ominous colour) by time and fungus. During the climactic siege by the Sinn Feiners it will be violated by gelignite ߝ incompetently, alas, leaving the monarch still mounted but obscenely skirtless. The hotel’s fabric is in a condition of advanced decomposition. Its only residents are a crew of genteel old ladies no longer capable of paying their bills but with nowhere else to go. A comic moment of the hotel’s inexorable crumble conveys the distinctive tang of Farrell’s narrative:

One unseasonably warm day the giant m of majestic detached itself from the façade of the building and fell four storeys to demolish a small table at which a very old and very deaf lady, an early arrival for Christmas, had decided to take tea in the mild sunshine that was almost like summer. She had looked away for a moment, she explained to Edward in a very loud voice (almost shouting, in fact), trying to remember where the floral clock had been in the old days. She had maybe closed her eyes for a moment or two. When she turned back to her tea, it had gone! Smashed to pieces by this strange, seagull-shaped piece of cast iron (she luckily had not recognized it or divined where it had come from). [pp. 545ߝ6]

It would be a dull reader who did not pick up the primary allegory. It glows radioactively. Colonial Ireland itself is in terminal decay. But the allegory is spiced by Farrell’s idiosyncratic sense of the absolute absurdity of things ߝ even things which the mass of us find rather serious. One can’t help feeling sometimes he is laughing at us.

After Angela’s surprising death, Archer falls in love with a local Catholic woman much smarter than he and disinclined to do more than toy, cat-and-mouse style, with her bumbling English admirer. Spencer, meanwhile, goes certifiably mad. The civil unrest heats up to the point of rebellion. There is the de rigueur siege, but so disintegrated is the Majestic that it collapses and burns down of its own structural weakness leaving, among the ashes, a wilderness of 250 indestructible toilet pans and wash-basins.

Troubles received polite but grudging reviews. A scathing denunciation in the New Statesman, which took deep offence at his pas sérieux tone, caused Farrell some serious irritation. It was a hard novel to get hold of in the, once again, troubled early 1970s. Could one decently smile at Farrell’s Irish comedy with bombs going off in London or some poor child being blown to smithereens on the Falls Road?

It took years ߝ forty, to be precise ߝ before Troubles could be read as it should. In 2010 the Booker committee, convened to nominate the best novel of the Prize’s ‘lost year’, 1970 gave the award to Troubles. It would have been piquant for Farrell (dead thirty years) to have seen the New Statesman join, belatedly, in the chorus of acclaim, instructing its readers to take Troubles on holiday with them as their beach book.