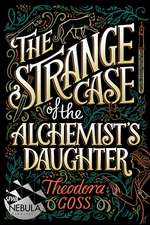

The Sinister Mystery of the Mesmerizing Girl: The Extraordinary Adventures of the Athena Club, cartea 3

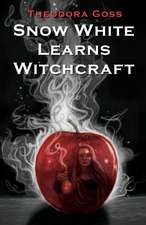

Autor Theodora Gossen Limba Engleză Paperback – 23 iul 2020

Life’s always an adventure for the Athena Club...especially when one of their own has been kidnapped! After their thrilling European escapades rescuing Lucina van Helsing, Mary Jekyll, and her friends return home to discover that their friend and kitchen maid Alice has vanished—and so has their friend and employer Sherlock Holmes!

As they race to find Alice and bring her home safely, they discover that Alice and Sherlock’s kidnapping are only one small part of a plot that threatens Queen Victoria, and the very future of the British Empire. Can Mary, Diana, Beatrice, Catherine, and Justine save their friends—and the Empire?

In the final volume of the trilogy that Publishers Weekly called “a tour de force of reclaiming the narrative, executed with impressive wit and insight” in a starred review, the women of the Athena Club will embrace their monstrous pasts to create their own destinies.

Preț: 53.73 lei

Preț vechi: 65.12 lei

-17% Nou

Puncte Express: 81

Preț estimativ în valută:

10.28€ • 10.73$ • 8.51£

10.28€ • 10.73$ • 8.51£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 21 martie-02 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781534427884

ISBN-10: 1534427880

Pagini: 464

Ilustrații: f-c cvr

Dimensiuni: 140 x 210 x 36 mm

Greutate: 0.36 kg

Editura: S&S/Saga Press

Colecția S&S/Saga Press

Seria The Extraordinary Adventures of the Athena Club

ISBN-10: 1534427880

Pagini: 464

Ilustrații: f-c cvr

Dimensiuni: 140 x 210 x 36 mm

Greutate: 0.36 kg

Editura: S&S/Saga Press

Colecția S&S/Saga Press

Seria The Extraordinary Adventures of the Athena Club

Notă biografică

Theodora Goss is the World Fantasy Award–winning author of many publications, including the short story collection In the Forest of Forgetting; Interfictions, a short story anthology coedited with Delia Sherman; Voices from Fairyland, a poetry anthology with critical essays and a selection of her own poems; The Thorn and the Blossom, a novella in a two-sided accordion format; and the poetry collection Songs for Ophelia; and the novels, The Strange Case of the Alchemist’s Daughter, European Travel for the Monstrous Gentlewoman, and The Sinister Mystery of the Mesmerizing Girl. She has been a finalist for the Nebula, Locus, Crawford, Seiun, and Mythopoeic Awards, as well as on the Tiptree Award Honor List, and her work has been translated into eleven languages. She teaches literature and writing at Boston University and in the Stonecoast MFA Program. Visit her at TheodoraGoss.com.

Extras

Chapter I: The Temple of IsisCHAPTER I

Princess Ayesha stared down into the lotus pool. The orange fish had hidden itself under one of the floating leaves. The lotus flower rose up, yellow and conical, perfectly still in the hot summer afternoon. A dragonfly landed on it, spreading its iridescent wings. The orange fish was also iridescent, and the water shimmered in the sunlight. It was as though everything here shimmered, nothing was stable, nothing ordinary—like a mirage. Would it all disappear? Would she be left sitting on desert sand? That, she had been told by her nurse, was what happened to travelers who ventured out beyond the verdure on either side of the river, beyond the date palm orchards and barley fields.

“Come, child,” said Queen Merope. “The High Priestess is ready to see us.”

She looked up at the queen. Her mother was the most beautiful woman she had ever seen—tall, with the long neck of an ibis, and slender hands just beginning to lose the suppleness of youth. Her skin was a burnished brown—she had come from Heliopolis, and was said to be descended from the ancient kings who had ruled Egypt, long before Alexander marched across the world and installed his general, Ptolemy, as its ruler. Ayesha took after her much darker father, who came of an even older lineage. She shaded her face with one hand—the sun was just over her mother’s shoulder. She opened her mouth to ask a question.

Her mother looked down at her, eyes rimmed with kohl—it was usually impossible to guess what Queen Merope was thinking. The black wig she wore over her shaved head had small bells sewn to the end of each braided strand, and they chimed softly as she moved. “Yes,” she said. “You do have to stay here. No, there is absolutely no use in arguing.” The queen held out her hand.

Ayesha shut her mouth, took the hand held out to her, and stood up. She was not quite as tall as her mother, but soon would be. Perhaps, after all, it was for the best? If she was not accepted into the temple, her father would arrange a marriage for her. Did she want to be married? Judging by her brothers, from her mother and her father’s other wives, boys were in general a great bore. They were always boasting, or going out to hunt, or getting drunk on honey wine. So perhaps it would be best after all to serve the Goddess here at Philae? Already she liked the temple, with its massive stone walls painted in bright colors and its great stone lions that looked as though they might be friendly, however fierce. And she liked this garden, with its still pools filled with lotus flowers, the small fountains, the tamarind trees.

The priestesses were a little too solemn—none of them seemed to smile, unlike the courtiers and servants of her father’s court. The one that had come to fetch them, for example—standing several steps behind her mother. She did not look Egyptian—Assyrian, perhaps? Priestesses came from all over the world to serve at Philae. She stood very still in her white linen robe, with a cloth wound around her head—the priestesses did not wear wigs. No kohl around her eyes, no carmine on her lips, no gold rings in her ears. Being a priestess was a serious business, evidently. Would Ayesha be as solemn when she was a priestess of Isis?

Queen Merope tugged sharply at her hand, and she followed her mother through the sunlit garden, into the cool, shadowed temple complex.

“You must be on your very best behavior,” said the Queen in a low voice. “Remember that the High Priestess was once queen of all Egypt. When the old King died and his son ascended the throne—his son by his first wife—she was sent here to serve the Goddess.”

“Did they not want her in Alexandria anymore?” asked Ayesha.

The Queen gave her a swift, shrewd glance. “It is a great honor to serve Isis,” she said, but her lips curved upward, as though she did not want to smile but could not help herself. My daughter is a clever one, she seemed to be thinking. “Anyway, it’s best to get out of the way when the sons and daughters of kings quarrel. We are done with that now, I hope, and Egypt is prosperous again—it is bad to have instability on our northern border. Although the Romans—well, this is no place to talk politics. You must show such honor to the High Priestess as you would show to your father’s mother. Do you understand?”

“Yes, Mother,” said Ayesha, listening with only half her attention. She always respected Nana Amakishakhete, didn’t she? It was Netekamani, her youngest brother, who was so disrespectful, pulling on Nana’s robe, asking for sesame seed cakes. The temple of Isis was almost as large as her father’s palace. She had been told that it was inhabited only by the priestesses—worshipers were allowed in on feast days, but not ordinary days, and the inner sanctum could be entered by the priestesses alone. What was it like? Soon, she would find out.

They passed through a series of bare stone halls, the slap of their sandals echoing back at them. At the entrance to the audience chamber, the priestess who had led them opened a set of painted cypress-wood doors that were twice as tall as she was. The audience chamber was large and shadowed. Sunlight shone in through tall, narrow windows, but did not reach the central dais. To either side of that dais stood priestesses in white linen robes, perfectly still and silent. On the dais itself was a stone chair, as plain as the throne of Egypt on the head of Isis in the carvings on the temple walls. On it sat a woman almost as old as Nana Amakishakhete. She had long white hair that she wore in a single braid down one shoulder. Ayesha could not help staring at it—everyone she knew, even her mother, had short curly hair, although it was generally shaved off. Servants replaced it with colorful head cloths, the fashionable people at court with elaborate wigs, in which gold and glass beads were intertwined. This woman was lighter than even Ayesha’s mother—it was clear that she came from the north, where Egyptian blood had mixed with Greek. But she did not look quite Alexandrian—Ayesha had seen envoys from that city and wondered at their strange, pale skin, which reminded her of the slugs that ate gourd leaves in the kitchen gardens. Sitting in her lap was the largest cat Ayesha had ever seen, pure black, which stared at her with unblinking yellow eyes.

The priestess who had led them bowed before the dais, and then moved to one side.

“Thank you, Heduana,” said the High Priestess, nodding at the priestess who had led them. “Come forward, child.”

Ayesha felt a hand on her right shoulder blade. Her mother propelled her forward until they were standing the correct ceremonial distance away from the dais, then bowed. Had Ayesha ever seen Queen Merope bow? She could not recall. She was almost too awed by the large, silent room and the small, wrinkled woman up on the stone chair to remember what she was supposed to do, but feeling once again the pressure of her mother’s hand, she knelt and bowed her head down to the floor until her forehead lay on the stone.

“You do the temple honor, bringing your daughter yourself, Queen of Meroë,” said the High Priestess. She had a foreign accent—not Greek, but close to it.

“You do Meroë honor allowing my daughter to come, Priestess of the Goddess with a Thousand Names, Bringer of Light and Abundance, Who Produces the Fruit of the Land,” said Merope. “She is not worthy, but if she should find favor in your eyes, I pray that you will accept her into the temple, to serve the Queen of Heaven.”

“Stand, child,” said the High Priestess. Ayesha lifted her head up from the stone floor. She was allowed to stand now, right? She looked up sideways at her mother, who gave her an almost imperceptible nod. She stood, awkwardly because she was feeling light-headed. For a moment the temple seemed to shimmer around her, as though it too were a mirage. Stop that, she told herself. After all, she was a princess of Meroë. She would not allow herself to be intimidated by this situation or any other.

The High Priestess stood, put the black cat on the stone chair behind her, and descended from her dais. The cat meowed in protest, but then sat like a statue of Bast with its tail curled around its legs. When the High Priestess reached out her left hand, Ayesha almost drew back in surprise and consternation. On that hand the High Priestess had seven fingers! But she had been trained well, by both her mother and Nana Amakishakhete. She did not flinch as the High Priestess lifted her chin, so that her eyes, which had been cast down in a sign of respect, looked directly into the dark eyes of the High Priestess, who considered her with as little emotion as though she were a rather interesting insect.

“Do you truly wish to serve the great Isis, with your heart and mind and spirit? Will you pledge yourself to her, leaving your father and mother, your sisters and brother, your house and your lands, giving up the ordinary life of a woman, to become one of our sisterhood, from now until the hour of your death?”

“Yes, High Priestess,” she answered as steadily as she could.

“My name is Tera, and here in this temple, my order is the word of the Goddess. You must obey me as you would her. That is the first of many things you will learn here.” The High Priestess withdrew her hand—Ayesha could feel a tingling in her chin where the High Priestess had rested her seven fingers. She turned to Queen Merope and said, “I accept your daughter into the temple as a novice. She shall go with Heduana to the dormitory where the novices sleep and learn the rituals of our order. If she serves the Goddess well for a year, she shall become a priestess at the Festival of the Inundation. You may bid her farewell. She is a daughter of Isis now, and the priestesses are her family. The tributes you have brought, which I understand are in a wagon outside the temples gates, may be brought in.”

Queen Merope bowed once again to the High Priestess, then turned to Ayesha. “Serve the Goddess well, my daughter,” she said.

Ayesha wished she could embrace her mother. She would have liked, once again, to inhale her mother’s scent—the fragrant oils in her wig, combined with the warm, human smell of her skin. But it would not be dignified in front of all these people.

Queen Merope leaned down and kissed her on the forehead, then turned and walked back out of the room, leaving her daughter behind. Ayesha watched her depart with trepidation. Did she truly want this new life? Was she ready to be a priestess of Isis? She did not know.

MARY: Why in the world are you starting with Ayesha? This is supposed to be a book about us.

CATHERINE: Our readers won’t understand what happens later if I don’t tell them about Ayesha—how she became a priestess and her time at the temple. Anyway, Egypt is very fashionable nowadays. Everyone wants Egyptian furniture, clothes, jewelry. Why not a book?

MARY: But this book isn’t about Egypt. It’s about—well, England. And us, as I said.

CATHERINE: Fine, I’ll start with us. But it’s not going to be anywhere near as exciting.

Mary Jekyll stared out the train window. She was so tired of traveling! Three days ago, she, her friend Justine Frankenstein, and her sister Diana Hyde had boarded the Orient Express in Budapest. They had disembarked at the Gare de l’Est in Paris, made their way to the Gare du Nord, and boarded another train from Paris to Calais. This train was not an express—to Mary, it seemed unbearably slow. Sometime that afternoon they would arrive in Calais and catch the ferry across the English Channel. Then yet another train from Dover to Charing Cross Station in London. And then a cab. And then—finally, finally—home. Sometimes in their travels she had missed the Jekyll residence at 11 Park Terrace terribly. Now, all the details of it came back to her: the front hall with its dark wood paneling and the mirror in which she checked to make sure that her hat was on straight, the parlor with a portrait of her mother above the mantel, the library where her father had once planned his experiments, the kitchen where Mrs. Poole presided, and her own bedroom, her very own bed, soft and cool. She would sleep in her own bed tonight.…

“You look very far away,” said Justine with a smile. Diana was asleep, sprawled on the seat beside Justine, with her head in the Giantess’s lap. At least she was not snoring!

“I was thinking about how happy I’m going to be to get home,” said Mary. “But what about you? Will you miss Europe?” After all, Justine was not English, although she had lived in England for more than a century—she had been born in Switzerland. Would she miss being able to speak French and German when they were back in London?

“I will miss it—a little,” said Justine. “Although I am in no sense a gourmande, I will miss the Austrian pastries. But I think I will miss our friends more.” Irene Norton, and her maids Hannah and Greta, in Vienna. Carmilla Karnstein and Laura Jennings in Styria. And of course Mary’s former governess Mina Murray and Count Dracula in Budapest. Without their help, the Athena Club would never have been able to rescue Lucinda Van Helsing from her father, the despicable Professor Abraham Van Helsing, who had been conducting experiments that turned his daughter into that dreadful thing—a vampire!

LUCINDA: Catherine, if you’ll forgive my interrupting, it really is not such a dreadful thing to be a vampire. I have a different diet than you do, that is all.

CATHERINE: Can’t you all just go away and let me write this book?

DIANA: Not if you’re going to get the details wrong! And you should be nicer to Lucinda. She can’t help being a blood-sucking creature of darkness.

CATHERINE: What sort of trash have you been reading now?

LUCINDA: Of darkness? But I do not require darkness.

Diana snorted in her sleep. Well, at least she was asleep! On the Orient Express, she had pestered Mary endlessly: Why did she have to wear women’s clothes? It was so much easier traveling as a boy. Justine was traveling as a boy, or rather man, so why couldn’t she? And why couldn’t they have taken one of Count Dracula’s puppies? There were plenty in the litter. And why couldn’t she have some money? Yes, all right, the last time she had stolen some of Mary’s francs to gamble with, but she had won more at Écarté. Anyway, it was so boring on the train. She would probably die of boredom.

“Because Justine is over six feet tall, and it’s too conspicuous for her to travel as a woman,” Mary had told her. “You are not over six feet tall—you’re not even five feet tall—and we need you to share a cabin with me. And because I don’t think Alpha or Omega would appreciate having one of the Count’s white wolfdogs in the house, plus Mrs. Poole would have a fit, and then where would we be?” But she had finally given Diana five francs, just to make her stop talking and go away. Diana had come back that evening with fifteen, won from a card game with the porters. Mary, thoroughly ashamed of her sister, had given half of it back in tips.

“I’m going to miss everyone too,” she said to Justine. “But it will be lovely to see Mrs. Poole again, and sit in our own parlor, and walk in Regent’s Park. If only I weren’t so worried about Alice and Mr. Holmes! And Dr. Watson, of course, if he is indeed missing as Mrs. Poole indicated in her telegram. Perhaps he’s simply on the case, as Mr. Holmes would say? It would be like him to go after Mr. Holmes and try to rescue him from whatever predicament he’s in. I hope Dr. Watson hasn’t actually disappeared, despite Mrs. Poole’s statement.”

“If so, would Mrs. Hudson not know his whereabouts?” asked Justine.

“Not necessarily. You know he and Mr. Holmes are—well, despite how much I like and respect them, they’re not always considerate. Sometimes they do not let anyone know where they are going, or what they are doing there.”

“Perhaps,” said Justine, seeming unconvinced. Then she added, “We’ll find them, Mary, wherever they are. We are the Athena Club, after all.” But she looked worried as well—Mary could see the small frown lines between her eyebrows.

Well, thought Mary, we have reason to be worried, the both of us! She remembered that afternoon in the basement storage room of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences—had it really only been four days ago? She, Justine, and Beatrice had been going through the files of the Alchemical Society when Catherine had rushed in, breathless, and said, “Telegram from Mrs. Poole!” The telegram had informed them that Alice, Mary’s kitchen maid, had been kidnapped. And then Frau Gottleib, who had once served in the Jekyll household as nurse to Mary’s mother, but whom they had discovered was actually a spy for the Alchemical Society, had told them that Alice was not who they had thought either. Although Alice herself did not know it, she was Lydia Raymond, daughter of the notorious Mrs. Raymond, who had been involved in the Whitechapel Murders.

MARY: How in the world do you keep all this straight in your head? It’s like a giant tangle of string. The hardest thing about our trip to Budapest was finding out that no one was who I thought they were—Nurse Adams, who took care of my mother for so long, was actually Eva Gottleib, and Mina wasn’t just my governess, but had been spying on me for the British Society’s Subcommittee on Bibliographic Citation Format, and Helen Raymond wasn’t just the director of the Society of St. Mary Magdalen, but the result of an experiment in biological transmutation by Dr. Raymond, who had been the chair of the British chapter of the Alchemical Society.…

CATHERINE: I keep notes, of course. Although sometimes it’s hard to remember things like dates and train schedules. You’re better at those sorts of things than I am.

As soon as they had learned that Alice was missing, Mary and Justine had packed their bags—and Mary had packed for Diana, to make sure she did not sneak a wolfdog into her suitcase! They had left the next day. Catherine and Beatrice had stayed to fulfill their contract with Lorenzo’s Circus of Marvels and Delights, which was performing in Budapest to packed houses, but they would leave as soon as their obligations were over. Mary would be glad when they were all back in London! Where were Alice, Mr. Holmes, and Dr. Watson? As soon as she and Justine arrived back at 11 Park Terrace, Mary would try to find out. Mrs. Raymond might be connected in some way—Mary still remembered the formidable director of the Magdalen Society, with her iron-gray hair and cold, hard eyes. Was the mysterious Dr. Raymond connected as well? This was another adventure, coming right on the heels of the last one—adventures seemed to do that. They never gave one enough time to rest. Whatever dangers awaited them in London, they would need the full strength of the Athena Club.

MARY: Are our readers going to know what the Athena Club is?

CATHERINE: They will if they read the first two books! Which they should, and I hope if they are reading this volume and have not read the previous ones, they will go right out and purchase them. Two shillings each, a bargain at the price!

While Mary was staring out the train window at the houses of Calais with their neat gardens, and mentally calculating how many francs she would have to pay for ferry tickets, Justine was also remembering their adventures in Europe. For the first time since she had been resurrected by Victor Frankenstein, she had been—not quite home, but almost. Hearing French and German, eating food whose flavors were familiar from her childhood, she had felt closer to home than she ever did in England. Driving in the coach through the mountains of Styria, even though they had been driving into a trap set by the despicable Edward Hyde, she had felt a sense of joy from the air and altitude. And then confronting Adam again! Frankenstein’s first creation, who had loved her and tortured her, if anything so cruel and desperate could be called love. In his letter to Mary, Hyde had written that Adam was dead. Justine wondered if she could believe him—she had once seen Adam die in a fire with her own eyes, and yet she had found him again, terribly injured, in Styria. But reason told her that he must be dead indeed, that he could not have survived those injuries much longer. When she had read Hyde’s letter, she had felt, for the first time in her second life, a sense of release from bondage, of that peace the Bible spoke of which passeth all understanding. It was wrong to rejoice in his death, and yet she could not help doing so. Well, she would pray about it in St. James’s, the church she and Beatrice attended across from Spanish Place. It would be nice to speak with Father O’Brian again!

How fortunate she was to have everything she needed: friends who loved her, a home to return to. The one thing she had truly missed had been her painting studio. That study of flowers in a blue vase was still sitting on her easel, unfinished. Would she have time to finish it when they got home? Perhaps after they had found Alice. Poor little Alice… where could she be? And then, like Mary, Justine worried about the kitchen maid, and Mr. Holmes, and Dr. Watson, all so mysteriously vanished.

While Mary and Justine’s train drew into the station at Calais, Catherine—

DIANA: What about me? You haven’t said anything about me. I was on that train too.

Diana continued to snore in her sleep. She woke only when the train lurched and she almost rolled off Justine’s lap and onto the floor. The first words out of her mouth were: “Bloody hell!” Since she had been asleep for the entire journey, she had not said or thought anything worth reporting.

CATHERINE: There, satisfied? Oh no, you don’t! If you kick me again, I’m going to bite you so hard.…

Meanwhile, Catherine was eating a very good sausage, flavored with red pepper, in the dining room of Count Dracula’s house in Budapest. Madam Zora, the circus’s snake charmer, had just been thanking Mina Murray for inviting her to stay at the Count’s town residence while the circus was performing.

“Don’t thank me,” said Mina with a smile. “I’m not the mistress here. The Count decides who stays or goes—sometimes unceremoniously! But he likes having all of you girls here—he says it gives this old mausoleum a semblance of life—and you are welcome to stay as long as you wish.”

“Beatrice and I would have gone already if the circus hadn’t been held over until Thursday!” said Catherine. “But Lorenzo’s making so much money—he says everyone who’s anyone is in Budapest right now, for the Emperor’s visit. The theater is packed every night. And if anyone deserves it, he does—considering all those years we traveled around the countryside in wagons, barely able to afford food for the trick ponies or performing dogs!”

“He’s giving us all double wages,” said Zora with satisfaction. “But thank you all the same, Mina. Not everyone would want a bunch of poisonous snakes in their house. I didn’t know what to do after one of them got loose and the hotel kicked me out. And it wasn’t even one of the poisonous ones, just Buttercup! She looks impressive—most people have never seen an albino python—but she wouldn’t hurt anyone, not really. I mean, unless they scared her.” Although on stage Zora spoke with the accent of the Mysterious East, this morning it was evident that the east she came from was Hackney in the East End of London. She ate the final bite of her omelet appreciatively.

Just then Kati, the parlor maid, came in carrying a silver tray. She said something to Mina in Hungarian—Catherine still could not make heads or tails of that language! Mina picked a piece of paper off the tray and looked at it intently. Even from the back, it had the distinctive appearance of a telegram.

“This is from Irene Norton,” said Mina, putting it down on the table. “She says she’s found the warehouse in Vienna where Van Helsing was creating and mesmerizing vampires, and where they still maintain a sort of nest. She asks if we’d like to join her for a vampire hunt. You and Beatrice need to get back to London, don’t you? But I could go. After all, I have developed a sort of expertise in vampires!”

“I pity Van Helsing’s vampires, with two such formidable opponents to deal with!” It was Count Dracula, who had entered as silently as he always did. Catherine looked him over with satisfaction. He was such a perfect romantic hero! Not, perhaps, particularly tall, but with the easy, upright carriage of an aristocrat and military man. High cheekbones, an aquiline nose, a forehead that indicated intellect, interesting pallor, and the sort of dark, floppy hair that would have delighted Mrs. Radcliffe. And he usually dressed in black. Yes, she would have to see if she could fit him into one of her books, somehow!

Mina turned to him with a frown, not of anger but as though she were thinking hard. “I should go, shouldn’t I? Irene has more resources than I do, but she has very little experience fighting vampires, whereas I—well, I’ve learned a great deal about them in the years since poor Lucy was transformed into one. You can’t come, I suppose, Vlad? Not with the Emperor himself arriving for a state visit this week?”

The Count shook his head. “Much as I would like to see a Hungary free of Austrian influence—I was proud to stand with Kossuth, and would again, despite the failure of our cause—I have official duties to perform. I must stay and represent my country. But you might ask Carmilla. It would take her no more than a day to drive from the schloss to Vienna, and she has always enjoyed hunting—even our kind, when they prove dangerous.”

Mina nodded. “I’ll send her a telegram today. I’m sure Irene could use all the help she can get.” She turned to Catherine and Zora. “Will you girls and Beatrice be all right here without me? You’re too old to need chaperones, I think.”

Catherine laughed. “I should think so! Anyway, Bea and I are leaving on Friday morning. We want to get back to London as soon as we can.”

“And Lorenzo’s circus is leaving too,” said Zora. “We’re booked all the way to Constantinople!”

Catherine could not help feeling envious. She would have liked to stay with the circus, playing her part as La Femme Panthère, the Panther Woman of the Andes, all the way to that fabled city. But the Athena Club needed her. How would they rescue Alice without her help?

DIANA: You’re not indispensable, you know!

JUSTINE: She certainly is! You are, Catherine. We could not do without you.

DIANA: You’re not going to edit that out, are you? You never edit out anything that makes you sound important.

But what were the Count and his parlor maid talking about? Kati was speaking to him in rapid Hungarian. He seemed to be arguing with her—he raised his hands and swept them through his hair in exasperation, creating even more perfect waves. She curtseyed and walked out of the room, holding the silver tray. “Kati!” he called after her; then to Catherine’s surprise he followed her out of the room, still expostulating.

“What in the world was that about?” asked Zora.

Mina looked both incredulous and amused. “Evidently, young Kati has decided to go work for Ayesha! Do you remember Ayesha’s assistant—Ibolya, I think her name was? Well, she and Kati were at school together, and Ibolya’s going off to Zurich to study medicine, so the President of the Alchemical Society needs a new assistant—and Kati has taken the job! She just gave her two weeks’ notice. You know how Vlad feels about that Ayesha—although to be honest, I think he was in love with her once, before she expelled him from the Alchemical Society. Not that I’m blaming her, considering the underhanded tactics he used in that election! I care for Vlad very much, but medieval Hungarian aristocrats don’t fight according to Hoyle.” She put her hand on the telegram and regarded it thoughtfully for a moment. “Sometimes I think he’s still a little in love with her, despite everything. Of course she offered this position to Kati to spite him—she’s still angry, and now he’s going to be angry as well. Over a parlor maid! Although I admit that Kati is an exceptionally good one. Anyway, he’s going to be impossible for the rest of the day. All right, I’m done with lunch. I need to telegraph Irene and Carmilla, then purchase a train ticket to Vienna. The two of you have tonight’s performance to prepare for. I wonder where Beatrice has gone off to. The cook prepared some lovely goop for her, and now it will go to waste.”

“She’s probably with Clarence somewhere,” said Catherine. “She seems to spend every waking moment with him nowadays.”

BEATRICE: That is not fair, Cat! Particularly when I was trying so hard not to spend time with him. I wanted him to forget me, to find—well, not someone else exactly, but perhaps something to do other than converse with a poisonous woman.

Beatrice was, in fact, with Clarence Jefferson at that moment, as Catherine had suspected. She looked around at the dark, paneled walls of the Centrál Kávéház. She and Clarence had gotten into the habit of coming here after rehearsals. She would sip an elderflower tisane and he would drink a dark, aromatic espresso. But this morning she had gone to the Hungarian Academy of Sciences for the first meeting of the Committee on Ethics in Alchemical Experimentation, so she and Clarence had decided to meet here for lunch and go on to rehearsals together. She was wearing the green dress she had been given by Mr. Worth himself in Paris, for no special reason—she had simply felt like wearing it this morning. Certainly she had not dressed up particularly for Clarence! Not that he ever seemed to notice what she was wearing, anyway. His attention always seemed to be entirely on her—although at the moment, some of it was focused on stirring his coffee.

He, too, seemed to have dressed with care, but then he always did, unless he was helping Atlas and the acrobatic Kaminski Brothers put up or take down sets. She could see in him the lawyer he had once been, before he had been tried and acquitted for murder—miraculously, for a black man in America who had shot and killed a white police officer, even before a crowd of witnesses who could swear it was in self-defense. That evening, he would be dressed as the Zulu Prince, who danced his native dances for an appreciative audience—one more attraction in Lorenzo’s Circus of Marvels and Delights.

She felt, once again, a deep sense of guilt that he was sitting here with her, when he could be with any number of women who were not poisonous and with whom he could have an ordinary relationship. She had told him that once—he had replied, touching her cheek for just a moment, not long enough for his fingertips to blister, “I don’t want ordinary, Bea. I want you.”

Now, he reached across the table and took her gloved hand. “Honey, you look a million miles away. What are you thinking?”

“That I will miss this place. Soon, Catherine and I will be returning to London, and you will be leaving with the circus for—where do you go next?”

“Bucharest, then Varna, then Constantinople. And after that… maybe Athens? Lorenzo wasn’t sure the last time I talked to him. I wish you could come with us. We could use a Poisonous Girl. By the way, how did the committee meeting go?”

“Well enough, I suppose. Frau Gottleib and Professor Holly agreed that the Société des Alchimistes needs a set of ethical rules to guide alchemical research. They asked me to produce a first draft for their comments and revisions. Once we agree on a second draft, we will present it to Ayesha. What she will think of it, only Heaven knows!”

“I’d like to meet this Ayesha,” said Clarence.

Beatrice looked at him with alarm. “Why? What is the President of the Alchemical Society to you?”

“Nothing, I suppose,” he said, looking at her with a puzzled frown, as though trying to understand her reaction. He pulled his hand away. “You told me she was a black woman—Egyptian, you said? And she’s the head of this Alchemical Society. She sounds impressive, and like someone I’d be interested in meeting, that’s all.”

Why had the thought of Clarence meeting Ayesha caused a sudden pang in her chest, as though she had been struck through the heart with one of Ayesha’s lightning bolts? Involuntarily, she put her hand where she had felt it. Yes, Ayesha was a beautiful woman, but that did not mean all men would fall in love with her, did it? Anyway it would be good for Clarence to fall in love with someone else… only not Ayesha. One could not compete with someone like Ayesha.

Clarence finished his soup, chicken in a paprika broth, and wiped the bowl with a piece of bread to get at the last of the spicy red liquid. Beatrice had already finished a cucumber salad. It was a little too substantial for her—she seldom ate anything that was not in liquid form—but she had felt awkward merely drinking while he ate. She did not know what to say, so she fiddled with her fork.

“Anyway, I must help rescue Alice, if indeed she has been kidnapped,” she said at last. “I am—we are all—terribly worried about her. The circus can get along very well without me, but the Athena Club—well, I would not want to abandon my friends.”

“Of course not, and I’m not asking you to.” Clarence ate a final piece of bread and signaled to the waiter. “I know how important the Athena Club is to—well, to all of you, including Cat. I just wish you and I could spend more time together.”

“But we should not spend more time together,” said Beatrice. “The more of my poison you inhale—”

“I know, I know, you don’t need to remind me.” He sounded impatient, annoyed. But she did need to keep reminding him, didn’t she? Because she did not want him to suffer the fate of her first love, Giovanni, who had spent so much time with her in her father’s garden that he too had become poisonous. He had died from drinking an antidote that he believed would return him to his natural state. No, she would not allow such a thing to happen to Clarence. It was good that soon they would be parted and he would go to Constantinople. There was no Ayesha in Constantinople.…

CATHERINE: So is it good or bad that Lorenzo’s circus has been offered a permanent position at the Alhambra? You get to see him as often as you like—

BEATRICE: Which is not often enough for him! Truly, I do not know whether it is a good thing or a bad thing that Clarence and I can spend more time together. I know you disapprove, Cat—

CATHERINE: I don’t disapprove. I just don’t want him to die of poison. Well, at least he didn’t fall for Ayesha, which would have been worse!

BEATRICE: He did, just a little. It’s difficult not to, I think.

Clarence paid the bill. Beatrice had tried, the first time they had come to the Centrál Kávéház, to pay for herself, but he had said, “Honey, at least allow me to do this.” So she had not insisted.

After they rose from the table, he took her manteau from the back of her chair and draped it over her shoulders. When they had first started spending time together, gestures like these had confused her. Certainly her father had never done such things, nor Giovanni, either. Slowly, she had come to realize they were the gestures men made toward women when they wished to be courteous, or romantic, or both. And Clarence was unfailingly courteous toward women, even when he was angry, as he had been at Zora for losing one of her snakes in the hotel. The entire circus had been asked to leave, but allowed to stay after Zora had promised to remove herself and her snakes to Count Dracula’s residence.

Sometimes, Beatrice could not help being amused by the incongruity of it. He walked between her and the street, so her skirt would not be splashed by passing carriages. And yet she could, with her breath, poison everyone on the sidewalk! Nevertheless, she could not help feeling pleasure at being cared for in this way—she, who had always cared for others, whether her father, or his poisonous plants, or the patients for whom she so carefully concocted medicines.

They emerged into Károlyi Mihály utca, into the warmth and sunlight of Budapest. Yes indeed, she would miss this city, which reminded her just a little of her own Padua, arranged along the Bacchiglione River, as Budapest was arranged along the Danube. The streets of Budapest were busy with carts and wagons, as they always were at midday. Clarence held his arm out to her. As usual, she did not take it. Instead, with a small shake of her head, she started down the street toward the theater. Although her arms and hands were thoroughly covered, and he could not, even by accident, have come into contact with her skin, she did not want him to get used to being close to her. That would not be good for him—or her, either. Her heart had been broken once—she did not want it broken again. She had found so much in this new life of hers: freedom and friendship and a purpose. Love was not necessary.

MARY: Are you quite sure about that? I would not say love is necessary—but perhaps life is not quite the same without it? We all need to be loved, in some way.

DIANA: I don’t.

MARY: I think you need to be loved more than anyone I know! Stop that—you can’t hurt me, kicking me through a petticoat. See? If I didn’t love you, I would never put up with such behavior. Of course, I don’t always like you very much.

BEATRICE: That does not change the fact that I am poisonous. I cannot be with any man without endangering his life. Lucinda would understand—she is not poisonous, but her hunger for blood also separates her from mankind.

MARY: Where is Lucinda, anyway?

CATHERINE: Playing the piano. Can’t you hear it? Good Lord, why do you primates have ears if you can barely hear with them?

At that moment, Lucinda Van Helsing was eating a rabbit. Or, more accurately, she was sucking its blood—later, Persephone and Hades, the Countess Karnstein’s white wolfdogs, would eat the carcass. Magda was standing beside her in the forest glade, looking down at her approvingly.

“Jó, jó,” she said, which Lucinda had come to understand meant “Good, good,” in Hungarian.

“You’re doing very well,” said Laura, who always came along on these hunting expeditions—“To translate,” she said, but Lucinda had quickly realized it was as much to comfort and reassure. The first time she killed a rabbit with her own hands, she had cried so hard that she almost vomited up all the blood she had drunk. Laura had taken Lucinda in her arms and stroked her hair, saying, “Hush, hush, my dear. You’ll get used to it in time.”

“I do not wish to kill,” she had said between sobs, stroking the bloodstained body of the dead rabbit as though it were her childhood doll.

“But you must learn to,” Laura had said. “Here at the schloss, if you wish it, we could have blood brought to you in a glass—you would never have to learn how to hunt for yourself, or confront the death inherent in your mode of obtaining sustenance. But that would be both dishonest and unwise. You don’t want to be dependent on others. And you are a predator—it is important for you to both understand and accept that fact. Carmilla would tell you the same herself, if she were here.”

However, Carmilla was not there, but at Castle Karnstein. She had spent most of that first week at her ancestral estate, dealing with the mess Hyde had left behind. Evidently, he had left without disposing either of his chemicals or the corpse of Adam Frankenstein, which had been left lying under a sheet in the small, dark chamber where he had spent his final days. “At least I can tell Justine that he is well and truly dead,” Carmilla had said to them on one of her brief visits. She had arranged for a proper burial in the graveyard behind the castle. Hyde had also neglected to pay his debts. He still owed money to the Ferenc family, which had served him so loyally while he had rented the castle. “Miklós and Dénes deserve to be horsewhipped for kidnapping Mary, Justine, and Diana on Hyde’s orders,” Carmilla had added angrily. “But I want to make sure Dénes can pay for his university tuition, and Anna Ferenc needs her medicine. The Ferencs have been tenants of the Karnsteins for two hundred years—I cannot let them starve. I’m sorry, Laura, but finances may be tight for a while.”

Laura had just sighed—she was all too used to finances being tight, partly through Carmilla’s extravagance. Now, she sighed again, but it seemed to be in relief that Lucinda had dispatched the rabbit so neatly. Lucinda simply nodded. What could she say? She was trying, as best she could, to live this new life her father had imposed on her through his experiments. She was a vampire—she would always be a vampire. She would always be able to hear the rabbit’s heart beating as she tracked it in the long grass; she would always be able to climb the tallest trees, hand over hand, as though she were a squirrel. She would never grow old or become ill from the diseases to which men are prone. She would not die unless her head was completely severed from her neck or she was burned so that her body could not regenerate itself. She would always have to drink blood.

She had thought of taking her own life—she still thought of it sometimes as she lay awake, late into the night, for she no longer seemed to need as much sleep. She had thought of somehow lighting herself on fire, burning herself down to ash. She had not told Laura about these thoughts, and she could not tell Carmilla. The Countess was too formidable—she seemed old and distant, although she looked no older than Lucinda. But Lucinda could not have told her anything so personal.

Now, she followed Laura back toward the schloss. Magda came behind with the carcass of the rabbit dangling from her hand. It would provide a meal for Persephone and her brother, Hades.

As they approached the back of the schloss, which had a long terrace, Carmilla came out through the French doors. “Telegram!” she called. She was holding a piece of paper in one hand.

“Who from?” asked Laura. “And when did you get back? I didn’t hear the motorcar. But then, we were pretty far into the forest.… Köszönöm, Magda,” she said, nodding to the—what was Magda exactly? A coachman, a gamekeeper, a protector of the household. She seemed to serve multiple functions. And, of course, she was a vampire—the only one created by Count Dracula who had managed to retain her sanity, or most of it. Sometimes she still imagined that she was on the battlefield, and then only Carmilla could subdue and restrain her. At first, Lucinda had been frightened of her, but Magda had been so kind—they had all been so kind to her. She was grateful for that.

Nevertheless, she was so very tired, and she smelled of blood. She would go up to her room, which had been Laura’s father’s room, once. She sometimes wondered what her life would have been like if her father had resembled Colonel Jennings—an ordinary man who liked his books and pipe, who wore the hunting jackets that still hung in the wardrobe or the slippers in a row beneath them. But no, her father had been the celebrated Professor Van Helsing, with appointments at several European universities and a desire to breach the boundaries of life itself, to make himself and men like him immortal. With a logic that still made her so furious she clenched her fists thinking about it, he had started by experimenting on his wife. Lucinda tried not to think about her mother too often—the memory was simply too painful. Her mother had died to save her from her father’s henchmen. Someday, the two of them would be reunited in Heaven, if vampires went to Heaven. If not, then in Hell. Until then, Lucinda would have to live somehow. At least, for the first time since her mother had been taken to the mental asylum, she was among friends.

Who seemed, at the moment, to be quarreling.

“But we just got home!” Laura was saying. “And you haven’t even been here most of the week, but at that wretched castle—”

“I can’t let Mina go into such a situation by herself, can I?” said Carmilla. “The Count won’t be able to leave Budapest until after the Emperor’s visit, so she’s going to Vienna alone. Do you want her confronting Van Helsing’s vampires without support?”

“First of all, she’s not going by herself,” said Laura. “She has Irene Norton there, and Irene has—well, a sort of gang, from what Mary told us. And second of all, that’s an excuse, and you know it. You just want to go off on your own, in that damned motorcar of yours, like some lone figure of righteous vengeance, to fight vampires. Must you be so dramatic? Honestly, sometimes I think you’re more like the Count than you realize.”

“Not alone. I want to take Magda with me. She’s so good at smelling out our kind. Kedvesem, I know you’re angry with me, don’t deny it—”

“Who’s denying it? Of course I’m angry with you,” said Laura angrily, as though to emphasize her point. “And you can’t take Magda. Lucinda needs her, particularly if you’re going to go off on a vampire hunt.”

“—but you also know I’m right. Do you really want Mina and Irene, and a group of girls who may be very capable but have no experience hunting such monsters, to go up against a nest of vampires without our help? All right, I’ll leave Magda here, but I at least need to go.”

Carmilla was holding Laura’s hand. Lucinda did not want to interrupt such an intimate scene—she felt a little shy even watching it. She would go up to her room, rinse her mouth out thoroughly with lavender water, and perhaps rest for a while. She still felt so awkward and ashamed about drinking blood. Would she ever get used to this new life as a vampire?

She entered through the French doors into the music room. Perhaps, before proceeding upstairs, she would play the piano for a few minutes. She sat down on the stool, which was adjusted to her height—she was the only one who played with any consistency. Ten minutes later, she did not even notice Laura tiptoeing across the room so as not to disturb her. She was so completely lost in the melodies of Shubert.

MARY: As she seems to be right now!

JUSTINE: Forgive me, Mary, but that is Chopin.

MARY: Oh. What’s the difference?

JUSTINE: Why, they are not at all alike! That is like asking what is the difference between Ingres and Renoir, between Delacroix and Monsieur Monet.…

CATHERINE: Are you seriously interrupting my narrative to argue about composers? “Lucinda was playing something or other on the piano.” There, I fixed it. Satisfied?

As the cab drew up to 11 Park Terrace, Mary could not stop looking out the window in all directions—at the gray, rainy streets of London, the Georgian houses on either side, and the trees waving over the housetops, reminding her that Regent’s Park was still there and now that she had returned, she could walk to it whenever she wished.

“Stop shoving me!” said Diana, who was sandwiched between Mary and Justine. She was awake but tired, and therefore especially cross.

The horse stopped right in front of the Jekyll residence. “Whoa, Caesar!” shouted the cabbie. It was lovely to hear a cockney accent again!

At Charing Cross Station, they had stopped for tea and currant buns in a tea shop—the first proper English tea Mary had been able to order since leaving for Europe. How welcome and familiar it tasted, although Diana complained that the buns were stale. And then they had caught a cab. Now here they were, at 11 Park Terrace once again, a month after they had left. In that month, she had experienced so many things! Sometimes they had been wonderful, sometimes terrifying, sometimes merely tedious. She would, she was sure, have such adventures again. But this was where she belonged—no matter how far away she traveled, it was the home to which she would always return.

She paid the cabbie, almost handing him francs by accident and reminding herself that she would need to exchange them as soon as possible at the Bank of England. Justine, in her incarnation as Mr. Justin Frank, helped the cabbie carry the trunk to the front stoop. Diana rang the bell an unnecessary number of times. Over it was a polished brass plaque on which was written THE ATHENA CLUB. Mrs. Poole should be expecting them—Mary had telegraphed from Calais.

But it was not Mrs. Poole who answered the door.

“What the hell?” said Diana.

Standing in the doorway was a boy—short, with ginger hair and a strange, angular face. His wrists stuck out of his suit jacket and his arms seemed strangely long.

“You rang, miss?” he said in what sounded like a foreign accent.

With a start, Mary realized who he must be: the Orangutan Man that Catherine had rescued from the British headquarters of the Alchemical Society in Soho. What had she called him? Archimedes? Archi—

“Miss Mary! Welcome home!” Ah, there was Mrs. Poole, hurrying down the hall behind him. She still had a white apron over her black housekeeper’s dress. “Miss Justine! I’m so glad to see you again. And even you, Miss Scamp!” She looked just as she always did: entirely reassuring. All Mary’s life, Mrs. Poole had been there, to guide and teach and sometimes reprove. She, more than anything else in that house—Dr. Jekyll’s books, Mrs. Jekyll’s portrait—made the Jekyll residence feel like home. Mary wondered how Mrs. Poole would respond if she kissed the housekeeper. She did not think Mrs. Poole would approve at all.

MRS. POOLE: I most certainly would not have. I know my place, I assure you. And I trust Miss Mary to know hers.

Instead she said, as heartily as she could, “Mrs. Poole, I’m so very, very glad to see you again. It’s so good to be home.” But even as she said the word, she realized how different her home was now from the house in which she had grown up as the proper Miss Jekyll. Here she was standing in the front hall with her sister Diana, who was glaring suspiciously at the Orangutan Man. Beside her stood Justine, and in a few days Catherine and Beatrice would be home as well. They had all changed that house—for the better. The Jekyll residence had become the Athena Club.

And Mary herself, returning after almost a month on the continent, was not the same Mary Jekyll who had left. She had heard different languages, tasted different flavors, paid in different currencies—she had met men like Dr. Freud and Count Dracula, women like Ayesha and Mrs. Norton. She had wandered the streets of Vienna and Budapest. No wonder she felt different. Perhaps travel did that to you. Mary had come home, but she was not the same Mary who had left—not quite.

However, this was no time for reverie. They had coats and hats to take off, luggage to unpack, and friends to find—or, if Mrs. Poole’s fears were justified, to rescue.

MARY: I worry that readers who begin with this volume will not understand who we are, how we formed the Athena Club, and why it was so important to rescue Alice. I know you should begin a novel in medias res, Cat, but perhaps this is too much in medias and not enough res?

AUTHOR’S NOTE: Reader, if you have not yet read the first two adventures of the Athena Club, The Strange Case of the Alchemist’s Daughter and European Travel for the Monstrous Gentlewoman, I encourage you to do so before proceeding further. However, I understand there may be reasons why you are unable to do so at this time. For example, if you have lost your fortune, must work as a governess, and cannot afford the first two volumes. Or if you have been kidnapped by bandits who possess only this third volume in their hideout, no doubt stolen from a person of discernment and literary taste. For readers in such circumstances, I shall briefly summarize our previous adventures, in which Mary Jekyll, impoverished after her mother’s death, discovered that her father, the respectable Dr. Jekyll, had engaged in experiments that turned him into the disreputable Mr. Hyde. When he fled England as a known murderer, he left behind a child, Diana Hyde, who was raised by the Society of St. Mary Magdalen, where Mrs. Raymond presided as the redoubtable director. Mary had taken the poor, defenseless girl home with her.

DIANA: Defenseless, my arse!

But her investigations had not ended there, for her father had been a member of the secretive Alchemical Society, some of whose members had also produced monstrous offspring: Beatrice Rappaccini, as poisonous as she was beautiful; Justine Frankenstein, taller and stronger than most men; and your author, Catherine Moreau, a puma transformed into a woman who retained her feline swiftness and cunning. Together, these remarkable young ladies had formed the Athena Club. These events are described in The Strange Case of the Alchemist’s Daughter, in which our heroines solved the Whitechapel Murders with the help of Mr. Holmes and Dr. Watson. In the thrilling sequel, European Travel for the Monstrous Gentlewoman, they rescued Lucinda Van Helsing and confronted the Alchemical Society with its crimes. While its formidable president, Ayesha, would not agree to halt experiments in biological transmutation entirely, she had agreed to form a committee to evaluate such experiments, with Beatrice as a member.

BEATRICE: It does not sound very impressive when you put it like that, and yet the committee has done some very good work. The research protocols I drafted have been adopted by the society, and I believe they have changed how such experiments are carried out. What Dr. Raymond did to Helen, for example—he could not do that, under our current structure.

All of these adventures and more can be found in the first two books, offered for the very reasonable price of two shillings a volume, in an attractive green cloth cover. Copies may be purchased in most fine bookstores.

MARY: This was supposed to be a synopsis, not an advertisement!

CATHERINE: Well, I don’t earn royalties on a synopsis, and we need money, especially now that Lucinda is staying with us.

MRS. POOLE: Remarkably cheap she is, compared with you lot! Even goes out and gets her own food, now she’s gotten the hang of it.

MARY: About which the less said, the better.

CHAPTER I ![]() The Temple of Isis

The Temple of Isis

Princess Ayesha stared down into the lotus pool. The orange fish had hidden itself under one of the floating leaves. The lotus flower rose up, yellow and conical, perfectly still in the hot summer afternoon. A dragonfly landed on it, spreading its iridescent wings. The orange fish was also iridescent, and the water shimmered in the sunlight. It was as though everything here shimmered, nothing was stable, nothing ordinary—like a mirage. Would it all disappear? Would she be left sitting on desert sand? That, she had been told by her nurse, was what happened to travelers who ventured out beyond the verdure on either side of the river, beyond the date palm orchards and barley fields.

“Come, child,” said Queen Merope. “The High Priestess is ready to see us.”

She looked up at the queen. Her mother was the most beautiful woman she had ever seen—tall, with the long neck of an ibis, and slender hands just beginning to lose the suppleness of youth. Her skin was a burnished brown—she had come from Heliopolis, and was said to be descended from the ancient kings who had ruled Egypt, long before Alexander marched across the world and installed his general, Ptolemy, as its ruler. Ayesha took after her much darker father, who came of an even older lineage. She shaded her face with one hand—the sun was just over her mother’s shoulder. She opened her mouth to ask a question.

Her mother looked down at her, eyes rimmed with kohl—it was usually impossible to guess what Queen Merope was thinking. The black wig she wore over her shaved head had small bells sewn to the end of each braided strand, and they chimed softly as she moved. “Yes,” she said. “You do have to stay here. No, there is absolutely no use in arguing.” The queen held out her hand.

Ayesha shut her mouth, took the hand held out to her, and stood up. She was not quite as tall as her mother, but soon would be. Perhaps, after all, it was for the best? If she was not accepted into the temple, her father would arrange a marriage for her. Did she want to be married? Judging by her brothers, from her mother and her father’s other wives, boys were in general a great bore. They were always boasting, or going out to hunt, or getting drunk on honey wine. So perhaps it would be best after all to serve the Goddess here at Philae? Already she liked the temple, with its massive stone walls painted in bright colors and its great stone lions that looked as though they might be friendly, however fierce. And she liked this garden, with its still pools filled with lotus flowers, the small fountains, the tamarind trees.

The priestesses were a little too solemn—none of them seemed to smile, unlike the courtiers and servants of her father’s court. The one that had come to fetch them, for example—standing several steps behind her mother. She did not look Egyptian—Assyrian, perhaps? Priestesses came from all over the world to serve at Philae. She stood very still in her white linen robe, with a cloth wound around her head—the priestesses did not wear wigs. No kohl around her eyes, no carmine on her lips, no gold rings in her ears. Being a priestess was a serious business, evidently. Would Ayesha be as solemn when she was a priestess of Isis?

Queen Merope tugged sharply at her hand, and she followed her mother through the sunlit garden, into the cool, shadowed temple complex.

“You must be on your very best behavior,” said the Queen in a low voice. “Remember that the High Priestess was once queen of all Egypt. When the old King died and his son ascended the throne—his son by his first wife—she was sent here to serve the Goddess.”

“Did they not want her in Alexandria anymore?” asked Ayesha.

The Queen gave her a swift, shrewd glance. “It is a great honor to serve Isis,” she said, but her lips curved upward, as though she did not want to smile but could not help herself. My daughter is a clever one, she seemed to be thinking. “Anyway, it’s best to get out of the way when the sons and daughters of kings quarrel. We are done with that now, I hope, and Egypt is prosperous again—it is bad to have instability on our northern border. Although the Romans—well, this is no place to talk politics. You must show such honor to the High Priestess as you would show to your father’s mother. Do you understand?”

“Yes, Mother,” said Ayesha, listening with only half her attention. She always respected Nana Amakishakhete, didn’t she? It was Netekamani, her youngest brother, who was so disrespectful, pulling on Nana’s robe, asking for sesame seed cakes. The temple of Isis was almost as large as her father’s palace. She had been told that it was inhabited only by the priestesses—worshipers were allowed in on feast days, but not ordinary days, and the inner sanctum could be entered by the priestesses alone. What was it like? Soon, she would find out.

They passed through a series of bare stone halls, the slap of their sandals echoing back at them. At the entrance to the audience chamber, the priestess who had led them opened a set of painted cypress-wood doors that were twice as tall as she was. The audience chamber was large and shadowed. Sunlight shone in through tall, narrow windows, but did not reach the central dais. To either side of that dais stood priestesses in white linen robes, perfectly still and silent. On the dais itself was a stone chair, as plain as the throne of Egypt on the head of Isis in the carvings on the temple walls. On it sat a woman almost as old as Nana Amakishakhete. She had long white hair that she wore in a single braid down one shoulder. Ayesha could not help staring at it—everyone she knew, even her mother, had short curly hair, although it was generally shaved off. Servants replaced it with colorful head cloths, the fashionable people at court with elaborate wigs, in which gold and glass beads were intertwined. This woman was lighter than even Ayesha’s mother—it was clear that she came from the north, where Egyptian blood had mixed with Greek. But she did not look quite Alexandrian—Ayesha had seen envoys from that city and wondered at their strange, pale skin, which reminded her of the slugs that ate gourd leaves in the kitchen gardens. Sitting in her lap was the largest cat Ayesha had ever seen, pure black, which stared at her with unblinking yellow eyes.

The priestess who had led them bowed before the dais, and then moved to one side.

“Thank you, Heduana,” said the High Priestess, nodding at the priestess who had led them. “Come forward, child.”

Ayesha felt a hand on her right shoulder blade. Her mother propelled her forward until they were standing the correct ceremonial distance away from the dais, then bowed. Had Ayesha ever seen Queen Merope bow? She could not recall. She was almost too awed by the large, silent room and the small, wrinkled woman up on the stone chair to remember what she was supposed to do, but feeling once again the pressure of her mother’s hand, she knelt and bowed her head down to the floor until her forehead lay on the stone.

“You do the temple honor, bringing your daughter yourself, Queen of Meroë,” said the High Priestess. She had a foreign accent—not Greek, but close to it.

“You do Meroë honor allowing my daughter to come, Priestess of the Goddess with a Thousand Names, Bringer of Light and Abundance, Who Produces the Fruit of the Land,” said Merope. “She is not worthy, but if she should find favor in your eyes, I pray that you will accept her into the temple, to serve the Queen of Heaven.”

“Stand, child,” said the High Priestess. Ayesha lifted her head up from the stone floor. She was allowed to stand now, right? She looked up sideways at her mother, who gave her an almost imperceptible nod. She stood, awkwardly because she was feeling light-headed. For a moment the temple seemed to shimmer around her, as though it too were a mirage. Stop that, she told herself. After all, she was a princess of Meroë. She would not allow herself to be intimidated by this situation or any other.

The High Priestess stood, put the black cat on the stone chair behind her, and descended from her dais. The cat meowed in protest, but then sat like a statue of Bast with its tail curled around its legs. When the High Priestess reached out her left hand, Ayesha almost drew back in surprise and consternation. On that hand the High Priestess had seven fingers! But she had been trained well, by both her mother and Nana Amakishakhete. She did not flinch as the High Priestess lifted her chin, so that her eyes, which had been cast down in a sign of respect, looked directly into the dark eyes of the High Priestess, who considered her with as little emotion as though she were a rather interesting insect.

“Do you truly wish to serve the great Isis, with your heart and mind and spirit? Will you pledge yourself to her, leaving your father and mother, your sisters and brother, your house and your lands, giving up the ordinary life of a woman, to become one of our sisterhood, from now until the hour of your death?”

“Yes, High Priestess,” she answered as steadily as she could.

“My name is Tera, and here in this temple, my order is the word of the Goddess. You must obey me as you would her. That is the first of many things you will learn here.” The High Priestess withdrew her hand—Ayesha could feel a tingling in her chin where the High Priestess had rested her seven fingers. She turned to Queen Merope and said, “I accept your daughter into the temple as a novice. She shall go with Heduana to the dormitory where the novices sleep and learn the rituals of our order. If she serves the Goddess well for a year, she shall become a priestess at the Festival of the Inundation. You may bid her farewell. She is a daughter of Isis now, and the priestesses are her family. The tributes you have brought, which I understand are in a wagon outside the temples gates, may be brought in.”

Queen Merope bowed once again to the High Priestess, then turned to Ayesha. “Serve the Goddess well, my daughter,” she said.

Ayesha wished she could embrace her mother. She would have liked, once again, to inhale her mother’s scent—the fragrant oils in her wig, combined with the warm, human smell of her skin. But it would not be dignified in front of all these people.

Queen Merope leaned down and kissed her on the forehead, then turned and walked back out of the room, leaving her daughter behind. Ayesha watched her depart with trepidation. Did she truly want this new life? Was she ready to be a priestess of Isis? She did not know.

MARY: Why in the world are you starting with Ayesha? This is supposed to be a book about us.

CATHERINE: Our readers won’t understand what happens later if I don’t tell them about Ayesha—how she became a priestess and her time at the temple. Anyway, Egypt is very fashionable nowadays. Everyone wants Egyptian furniture, clothes, jewelry. Why not a book?

MARY: But this book isn’t about Egypt. It’s about—well, England. And us, as I said.

CATHERINE: Fine, I’ll start with us. But it’s not going to be anywhere near as exciting.

Mary Jekyll stared out the train window. She was so tired of traveling! Three days ago, she, her friend Justine Frankenstein, and her sister Diana Hyde had boarded the Orient Express in Budapest. They had disembarked at the Gare de l’Est in Paris, made their way to the Gare du Nord, and boarded another train from Paris to Calais. This train was not an express—to Mary, it seemed unbearably slow. Sometime that afternoon they would arrive in Calais and catch the ferry across the English Channel. Then yet another train from Dover to Charing Cross Station in London. And then a cab. And then—finally, finally—home. Sometimes in their travels she had missed the Jekyll residence at 11 Park Terrace terribly. Now, all the details of it came back to her: the front hall with its dark wood paneling and the mirror in which she checked to make sure that her hat was on straight, the parlor with a portrait of her mother above the mantel, the library where her father had once planned his experiments, the kitchen where Mrs. Poole presided, and her own bedroom, her very own bed, soft and cool. She would sleep in her own bed tonight.…

“You look very far away,” said Justine with a smile. Diana was asleep, sprawled on the seat beside Justine, with her head in the Giantess’s lap. At least she was not snoring!

“I was thinking about how happy I’m going to be to get home,” said Mary. “But what about you? Will you miss Europe?” After all, Justine was not English, although she had lived in England for more than a century—she had been born in Switzerland. Would she miss being able to speak French and German when they were back in London?

“I will miss it—a little,” said Justine. “Although I am in no sense a gourmande, I will miss the Austrian pastries. But I think I will miss our friends more.” Irene Norton, and her maids Hannah and Greta, in Vienna. Carmilla Karnstein and Laura Jennings in Styria. And of course Mary’s former governess Mina Murray and Count Dracula in Budapest. Without their help, the Athena Club would never have been able to rescue Lucinda Van Helsing from her father, the despicable Professor Abraham Van Helsing, who had been conducting experiments that turned his daughter into that dreadful thing—a vampire!

LUCINDA: Catherine, if you’ll forgive my interrupting, it really is not such a dreadful thing to be a vampire. I have a different diet than you do, that is all.

CATHERINE: Can’t you all just go away and let me write this book?

DIANA: Not if you’re going to get the details wrong! And you should be nicer to Lucinda. She can’t help being a blood-sucking creature of darkness.

CATHERINE: What sort of trash have you been reading now?

LUCINDA: Of darkness? But I do not require darkness.

Diana snorted in her sleep. Well, at least she was asleep! On the Orient Express, she had pestered Mary endlessly: Why did she have to wear women’s clothes? It was so much easier traveling as a boy. Justine was traveling as a boy, or rather man, so why couldn’t she? And why couldn’t they have taken one of Count Dracula’s puppies? There were plenty in the litter. And why couldn’t she have some money? Yes, all right, the last time she had stolen some of Mary’s francs to gamble with, but she had won more at Écarté. Anyway, it was so boring on the train. She would probably die of boredom.

“Because Justine is over six feet tall, and it’s too conspicuous for her to travel as a woman,” Mary had told her. “You are not over six feet tall—you’re not even five feet tall—and we need you to share a cabin with me. And because I don’t think Alpha or Omega would appreciate having one of the Count’s white wolfdogs in the house, plus Mrs. Poole would have a fit, and then where would we be?” But she had finally given Diana five francs, just to make her stop talking and go away. Diana had come back that evening with fifteen, won from a card game with the porters. Mary, thoroughly ashamed of her sister, had given half of it back in tips.

“I’m going to miss everyone too,” she said to Justine. “But it will be lovely to see Mrs. Poole again, and sit in our own parlor, and walk in Regent’s Park. If only I weren’t so worried about Alice and Mr. Holmes! And Dr. Watson, of course, if he is indeed missing as Mrs. Poole indicated in her telegram. Perhaps he’s simply on the case, as Mr. Holmes would say? It would be like him to go after Mr. Holmes and try to rescue him from whatever predicament he’s in. I hope Dr. Watson hasn’t actually disappeared, despite Mrs. Poole’s statement.”

“If so, would Mrs. Hudson not know his whereabouts?” asked Justine.

“Not necessarily. You know he and Mr. Holmes are—well, despite how much I like and respect them, they’re not always considerate. Sometimes they do not let anyone know where they are going, or what they are doing there.”

“Perhaps,” said Justine, seeming unconvinced. Then she added, “We’ll find them, Mary, wherever they are. We are the Athena Club, after all.” But she looked worried as well—Mary could see the small frown lines between her eyebrows.

Well, thought Mary, we have reason to be worried, the both of us! She remembered that afternoon in the basement storage room of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences—had it really only been four days ago? She, Justine, and Beatrice had been going through the files of the Alchemical Society when Catherine had rushed in, breathless, and said, “Telegram from Mrs. Poole!” The telegram had informed them that Alice, Mary’s kitchen maid, had been kidnapped. And then Frau Gottleib, who had once served in the Jekyll household as nurse to Mary’s mother, but whom they had discovered was actually a spy for the Alchemical Society, had told them that Alice was not who they had thought either. Although Alice herself did not know it, she was Lydia Raymond, daughter of the notorious Mrs. Raymond, who had been involved in the Whitechapel Murders.

MARY: How in the world do you keep all this straight in your head? It’s like a giant tangle of string. The hardest thing about our trip to Budapest was finding out that no one was who I thought they were—Nurse Adams, who took care of my mother for so long, was actually Eva Gottleib, and Mina wasn’t just my governess, but had been spying on me for the British Society’s Subcommittee on Bibliographic Citation Format, and Helen Raymond wasn’t just the director of the Society of St. Mary Magdalen, but the result of an experiment in biological transmutation by Dr. Raymond, who had been the chair of the British chapter of the Alchemical Society.…

CATHERINE: I keep notes, of course. Although sometimes it’s hard to remember things like dates and train schedules. You’re better at those sorts of things than I am.

As soon as they had learned that Alice was missing, Mary and Justine had packed their bags—and Mary had packed for Diana, to make sure she did not sneak a wolfdog into her suitcase! They had left the next day. Catherine and Beatrice had stayed to fulfill their contract with Lorenzo’s Circus of Marvels and Delights, which was performing in Budapest to packed houses, but they would leave as soon as their obligations were over. Mary would be glad when they were all back in London! Where were Alice, Mr. Holmes, and Dr. Watson? As soon as she and Justine arrived back at 11 Park Terrace, Mary would try to find out. Mrs. Raymond might be connected in some way—Mary still remembered the formidable director of the Magdalen Society, with her iron-gray hair and cold, hard eyes. Was the mysterious Dr. Raymond connected as well? This was another adventure, coming right on the heels of the last one—adventures seemed to do that. They never gave one enough time to rest. Whatever dangers awaited them in London, they would need the full strength of the Athena Club.

MARY: Are our readers going to know what the Athena Club is?

CATHERINE: They will if they read the first two books! Which they should, and I hope if they are reading this volume and have not read the previous ones, they will go right out and purchase them. Two shillings each, a bargain at the price!

While Mary was staring out the train window at the houses of Calais with their neat gardens, and mentally calculating how many francs she would have to pay for ferry tickets, Justine was also remembering their adventures in Europe. For the first time since she had been resurrected by Victor Frankenstein, she had been—not quite home, but almost. Hearing French and German, eating food whose flavors were familiar from her childhood, she had felt closer to home than she ever did in England. Driving in the coach through the mountains of Styria, even though they had been driving into a trap set by the despicable Edward Hyde, she had felt a sense of joy from the air and altitude. And then confronting Adam again! Frankenstein’s first creation, who had loved her and tortured her, if anything so cruel and desperate could be called love. In his letter to Mary, Hyde had written that Adam was dead. Justine wondered if she could believe him—she had once seen Adam die in a fire with her own eyes, and yet she had found him again, terribly injured, in Styria. But reason told her that he must be dead indeed, that he could not have survived those injuries much longer. When she had read Hyde’s letter, she had felt, for the first time in her second life, a sense of release from bondage, of that peace the Bible spoke of which passeth all understanding. It was wrong to rejoice in his death, and yet she could not help doing so. Well, she would pray about it in St. James’s, the church she and Beatrice attended across from Spanish Place. It would be nice to speak with Father O’Brian again!

How fortunate she was to have everything she needed: friends who loved her, a home to return to. The one thing she had truly missed had been her painting studio. That study of flowers in a blue vase was still sitting on her easel, unfinished. Would she have time to finish it when they got home? Perhaps after they had found Alice. Poor little Alice… where could she be? And then, like Mary, Justine worried about the kitchen maid, and Mr. Holmes, and Dr. Watson, all so mysteriously vanished.

While Mary and Justine’s train drew into the station at Calais, Catherine—

DIANA: What about me? You haven’t said anything about me. I was on that train too.

Diana continued to snore in her sleep. She woke only when the train lurched and she almost rolled off Justine’s lap and onto the floor. The first words out of her mouth were: “Bloody hell!” Since she had been asleep for the entire journey, she had not said or thought anything worth reporting.

CATHERINE: There, satisfied? Oh no, you don’t! If you kick me again, I’m going to bite you so hard.…