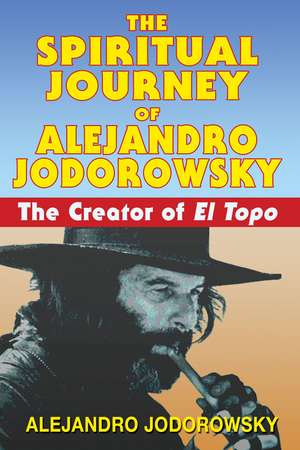

The Spiritual Journey of Alejandro Jodorowsky: The Creator of <i>El Topo</i>

Autor Alejandro Jodorowskyen Limba Engleză Paperback – 26 mai 2008

Preț: 118.58 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 178

Preț estimativ în valută:

22.69€ • 23.69$ • 18.78£

22.69€ • 23.69$ • 18.78£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 14-28 martie

Livrare express 27 februarie-05 martie pentru 32.71 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781594771736

ISBN-10: 1594771731

Pagini: 288

Ilustrații: Includes two 8-page b&w inserts

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Editura: Inner Traditions/Bear & Company

Colecția Park Street Press

ISBN-10: 1594771731

Pagini: 288

Ilustrații: Includes two 8-page b&w inserts

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Editura: Inner Traditions/Bear & Company

Colecția Park Street Press

Notă biografică

Alejandro Jodorowsky is a playwright, filmmaker, composer, mime, psychotherapist, and author of many books on spirituality and tarot, and over thirty comic books and graphic novels. He has directed several films, including The Rainbow Thief and the cult classics El Topo and The Holy Mountain. He lives in France.

Extras

From Chapter 2

THE SECRET OF KOANS

“Wait just a minute, Ejo. You say that you can’t solve koans with words, but I’m sure there are words that can dissolve them. Just as cobra venom can serve as an antidote to the poison of a bite, I believe one luminous, poetic phrase could nullify the question that has no possible answer.”

Ejo laughed. “If you believe that, then you must think you can do it. You confuse poetry with reality, but I accept the challenge. Give me a poetic response to the koan ‘What was your original face before your birth?’”

I concentrated intently and was about to say: “The same as my face after my death,” but I felt this would be falling into the trap of accepting the concept of birth and death by asserting that there is some face or individual form that we possess beyond this reality. So instead I exclaimed: “I don’t know! I didn’t have a mirror then!”

Ejo laughed again. “Quite ingenious. It is true that you have nullified the question with this exclamation--but what is the use of that? You remain a prisoner of having or not having. You accept that there is an original self, but you do not see it. Despite the fact that you managed to escape the duality of seer-seen, your words are still based on what you believe rather than on what you experience. In the traditional response, the disciple stands up and wordlessly places his two hands upon his chest. What do you think of that?”

I stood up, placed my hands upon my chest, and bowed.

Ejo smiled and went into the kitchen, returning with two cups of steaming coffee. As we drank it in the light of dawn, whose rosy hue was staining the dying blue of the night, Ejo lit a cigarette and inhaled the smoke with sensual delight. Noticing my disapproving air, he quoted a text from the Advaita Vedanta tradition, attributed to the poet Dattatraya: “Do not worry about the master’s defects. If you are wise, you will know how to make use of the good in him. When you cross a river, it may be in a boat painted in ugly colors, but you are thankful to it for helping you cross to the other side.”

For two or three days after that, I was in a state of euphoria. I walked the streets of the city and saw it all with new eyes. Everything seemed luminous to me. With every step I took, I rose up on my toes. I must confess, I felt I was enlightened. “Why do I need to keep seeing Ejo? When you resolve one koan, you resolve them all. Koans are not different truths; they are only different roads that lead us to the one and only light.” But then two humiliating events occurred in rapid succession and cut me down to size.

A young man named Julio Castillo came to see me. “Master, I want you to teach me about light,” he said.

My mind was flooded with an uncontrollable vanity, which I dissimulated by adopting a saintly expression. So this intelligent-looking youth was somehow able to perceive the degree of my spiritual attainment! I gave my best explanation of the nature of empty mind, detachment from desire and ego, and unity with the cosmos, the here and now. I read quotes to him from Hui-Neng and showed him photos of monks in meditation. Then I sat down in the zazen position and invited him to do likewise--but Julio Castillo only stood with a pained and embarrassed expression.

“Excuse me, master, but I fear there is a misunderstanding,” he murmured. “I am a theater student. I have come to ask you not to save my soul, but to teach me about light--how you place your projectors to get your effects on stage.”

I felt so ridiculous that I started coughing to hide my embarrassment.

The evening of that same day, I went to a party given by the surrealist painter Leonora Carrington. Her dazzling personality contrasted sharply with that of her husband, a man with a grave expression who rarely said anything and, when he did, uttered only a few syllables. In spite of the heat, he was wrapped in a thick, black overcoat, and a beret was pulled down to his ears. Like an observer from another planet, from a corner he watched the noisy party, where drink flowed copiously.

“Please don’t think he is some sort of ogre,” Leonora said to me. “Go talk with Chiki (as she called her husband)--you’ll see that he knows many interesting things. He reads five books a day. Right now he is studying Tibetan religion.”

It so happened that I had learned a very complicated Tibetan mudra (sacred hand gesture), which I had copied from a manuscript I had seen. With each thumb, I pulled the ring finger of the opposite hand toward my chest, and pressing the ring fingers against each palm, I brought together the two ring fingers like a symbolic mountain. I then used each of my index fingers to grasp the ring finger of the opposite hand and bring it down parallel to the little finger.

Approaching Chiki, I performed this complex operation and proudly displayed the mudra to him, asking him at the same time (with the hope of impressing him and starting an interesting conversation): “What is this?”

He shrugged. “Ten fingers.”

With this one stroke, like a violent wind sweeping away all garbage, he banished all metaphor from my mind. No matter how much I entangled my fingers, I would never arrive at truth, only at a symbol that was as useless as the mutterings of an idiot. Ten fingers are still ten fingers. Awkwardly, I excused myself and hurried away to drown my humiliation in a glass of tequila. There and then, I decided to continue my meditations with Ejo.

THE SECRET OF KOANS

“Wait just a minute, Ejo. You say that you can’t solve koans with words, but I’m sure there are words that can dissolve them. Just as cobra venom can serve as an antidote to the poison of a bite, I believe one luminous, poetic phrase could nullify the question that has no possible answer.”

Ejo laughed. “If you believe that, then you must think you can do it. You confuse poetry with reality, but I accept the challenge. Give me a poetic response to the koan ‘What was your original face before your birth?’”

I concentrated intently and was about to say: “The same as my face after my death,” but I felt this would be falling into the trap of accepting the concept of birth and death by asserting that there is some face or individual form that we possess beyond this reality. So instead I exclaimed: “I don’t know! I didn’t have a mirror then!”

Ejo laughed again. “Quite ingenious. It is true that you have nullified the question with this exclamation--but what is the use of that? You remain a prisoner of having or not having. You accept that there is an original self, but you do not see it. Despite the fact that you managed to escape the duality of seer-seen, your words are still based on what you believe rather than on what you experience. In the traditional response, the disciple stands up and wordlessly places his two hands upon his chest. What do you think of that?”

I stood up, placed my hands upon my chest, and bowed.

Ejo smiled and went into the kitchen, returning with two cups of steaming coffee. As we drank it in the light of dawn, whose rosy hue was staining the dying blue of the night, Ejo lit a cigarette and inhaled the smoke with sensual delight. Noticing my disapproving air, he quoted a text from the Advaita Vedanta tradition, attributed to the poet Dattatraya: “Do not worry about the master’s defects. If you are wise, you will know how to make use of the good in him. When you cross a river, it may be in a boat painted in ugly colors, but you are thankful to it for helping you cross to the other side.”

For two or three days after that, I was in a state of euphoria. I walked the streets of the city and saw it all with new eyes. Everything seemed luminous to me. With every step I took, I rose up on my toes. I must confess, I felt I was enlightened. “Why do I need to keep seeing Ejo? When you resolve one koan, you resolve them all. Koans are not different truths; they are only different roads that lead us to the one and only light.” But then two humiliating events occurred in rapid succession and cut me down to size.

A young man named Julio Castillo came to see me. “Master, I want you to teach me about light,” he said.

My mind was flooded with an uncontrollable vanity, which I dissimulated by adopting a saintly expression. So this intelligent-looking youth was somehow able to perceive the degree of my spiritual attainment! I gave my best explanation of the nature of empty mind, detachment from desire and ego, and unity with the cosmos, the here and now. I read quotes to him from Hui-Neng and showed him photos of monks in meditation. Then I sat down in the zazen position and invited him to do likewise--but Julio Castillo only stood with a pained and embarrassed expression.

“Excuse me, master, but I fear there is a misunderstanding,” he murmured. “I am a theater student. I have come to ask you not to save my soul, but to teach me about light--how you place your projectors to get your effects on stage.”

I felt so ridiculous that I started coughing to hide my embarrassment.

The evening of that same day, I went to a party given by the surrealist painter Leonora Carrington. Her dazzling personality contrasted sharply with that of her husband, a man with a grave expression who rarely said anything and, when he did, uttered only a few syllables. In spite of the heat, he was wrapped in a thick, black overcoat, and a beret was pulled down to his ears. Like an observer from another planet, from a corner he watched the noisy party, where drink flowed copiously.

“Please don’t think he is some sort of ogre,” Leonora said to me. “Go talk with Chiki (as she called her husband)--you’ll see that he knows many interesting things. He reads five books a day. Right now he is studying Tibetan religion.”

It so happened that I had learned a very complicated Tibetan mudra (sacred hand gesture), which I had copied from a manuscript I had seen. With each thumb, I pulled the ring finger of the opposite hand toward my chest, and pressing the ring fingers against each palm, I brought together the two ring fingers like a symbolic mountain. I then used each of my index fingers to grasp the ring finger of the opposite hand and bring it down parallel to the little finger.

Approaching Chiki, I performed this complex operation and proudly displayed the mudra to him, asking him at the same time (with the hope of impressing him and starting an interesting conversation): “What is this?”

He shrugged. “Ten fingers.”

With this one stroke, like a violent wind sweeping away all garbage, he banished all metaphor from my mind. No matter how much I entangled my fingers, I would never arrive at truth, only at a symbol that was as useless as the mutterings of an idiot. Ten fingers are still ten fingers. Awkwardly, I excused myself and hurried away to drown my humiliation in a glass of tequila. There and then, I decided to continue my meditations with Ejo.

Cuprins

Prologue

1 “Intellectual, Learn to Die!”

2 The Secret of Koans

3 A Surrealist Master

4 A Step in the Void

5 The Slashes of the Tigress’s Claws

6 The Donkey Was Not Ill-Tempered after So Many Blows from the Stick

7 From Skin to Soul

8 Like Snow in a Silver Vase

9 Work on the Essence

10 Master to Disciple, Disciple to Master, Disciple to Disciple, Master to Master

Appendix: A Collection of Anecdotes

The Works of Alejandro Jodorowsky

Index

Recenzii

"Rather than clarifying the meaning of his imagery, this book only inspires readers to enjoy its 'mystery'. . . . a worthy read, filled with growing pains and crises that end in artistic triumph and achievement of wisdom and compassion."

"Jodorowsky's interactions with the motley crew of magas are fascinating and his words are always entertaining . . . "

"How this man has lived into the koan of his life is intriguing and vividly related."

" . . . for anyone who enjoys reading memoirs about truly interesting and influential people, this is definitely a book to check out."

"Jodorowsky's interactions with the motley crew of magas are fascinating and his words are always entertaining . . . "

"How this man has lived into the koan of his life is intriguing and vividly related."

" . . . for anyone who enjoys reading memoirs about truly interesting and influential people, this is definitely a book to check out."

Descriere

Jodorowsky's memoirs of his experiences with Master Takata and the group of wisewomen--magiciennes--who influenced his spiritual growth.