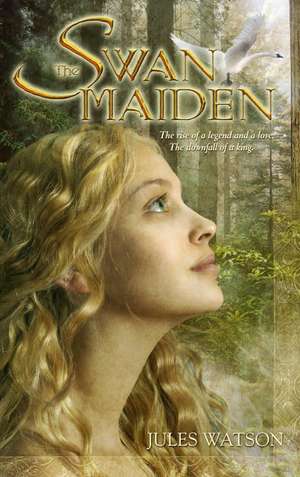

The Swan Maiden

Autor Jules Watsonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 ian 2009

She was born with a blessing and a curse: that she would grow into a woman of extraordinary beauty—and bring ruin to the kingdom of Ulster and its ruler, the wily Conor. Ignoring the pleadings of his druid to expel the infant, King Conor secrets the girl child with a poor couple in his province, where no man can covet her. There, under the tutelage of a shamaness, Deirdre comes of age in nature and magic…. And in the season of her awakening, the king is inexorably drawn to her impossible beauty.

But for Deirdre, her fate as a man’s possession is worse than death. And soon the green-eyed girl, at home in waterfall and woods, finds herself at the side of three rebellious young warriors. Among them is the handsome Naisi. His heart charged with bitterness toward the aging king, and growing in love for the defiant girl, Naisi will lead Deirdre far from Ulster—and into a war of wits, swords, and spirit that will take a lifetime to wage.

Brimming with life and its lusts, here is a soaring tale of enchantment and eternal passions—and of a woman who became legend.

Preț: 89.10 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 134

Preț estimativ în valută:

17.05€ • 17.62$ • 14.19£

17.05€ • 17.62$ • 14.19£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780553384642

ISBN-10: 0553384643

Pagini: 560

Dimensiuni: 133 x 159 x 32 mm

Greutate: 0.4 kg

Editura: Bantam

ISBN-10: 0553384643

Pagini: 560

Dimensiuni: 133 x 159 x 32 mm

Greutate: 0.4 kg

Editura: Bantam

Notă biografică

Jules Watson was born in Western Australia to English parents. After gaining degrees in archaeology and public relations, she worked as a freelance writer in both Australia and England. Jules and her Scottish husband divided their time between the U.K. and Australia before finally settling in the wild Highlands of Scotland. She is the author of the Dalriada trilogy—The White Mare, The Dawn Stag, and The Song of the North—a series of historical epics set in ancient Scotland about the wars between the Celts and the invading Romans. Kirkus Reviews named The White Mare among the top ten science fiction/fantasy releases of 2005, and The Song of the North was featured as a “Hot Read” in the Kirkus special science fiction/fantasy edition of 2008.

Extras

Chapter One

PUUQ

Leaf-fall

She was silver, an iridescence that arced along its trajectory like a falling star. The eagle hovered against the sky, wing-tips spread, and Deirdre imagined her spirit as a net that would capture it in a glittering sling of light.

Her body still lay in trance by the fire and she had to sum- mon immense focus to keep sending soul-breath along the thread that joined spirit and body. Now let the light sink in. It was Levarcham’s sibilant whisper, chanted into her ear. Her teacher’s will flowed beneath her, a current pushing her forward . . . upward.

The druid had fasted and sung with her for days, striking the drum until the sonorous pulse rang through both their bodies. Levarcham had endured the spasms and nausea of the herbs, all to fuse her energy with Deirdre and give her this fleeting chance of sacred flight.

The determination to stay focused on the soul-cord and the eagle at the same time was a keen pain, honed over moons of torturous practice. Deirdre was exhausted. It would be easier to fall back into her body. But she would not fail or waver.

Her own frustration had provided the force that initially flung her free, Levarcham’s will then lifting her, helping her break through the boundaries for one, long breath. There . . . She caught a flash of sensation: arms spread, a strange lightness of bones. The shock blanked her mind. Breathe, breathe! Levarcham urged.

Deirdre was gazing from other eyes. The rush of air peeled back wing-feathers and there was a blur of mountains, sunlight and shadow flitting across bare rock. At once, the eagle plunged into a dive and the land spun toward her. The bird opened its beak and screeched in ecstasy: freedom!

The one thing denied her. The one thing . . .

A resounding crash tore her from her trance.

She found herself sprawled in the rushes by an overturned stool with a jug glugging water into the rushes. A moment later, pain lanced her brow. “Deirdre!” Levarcham rasped, but she could not answer, clutching at the floor as it bucked beneath her, the walls of her little hut spinning.

The whirl of the room gradually slowed, and eventually lurched and stopped. A sense of her surroundings began to seep back in. Not air, not sun . . . but flickering light on curved mud walls and low thatch roof. Crackling flames drove the chill from the door-hide, and there was a lingering tang of herb smoke. Then Levarcham tossed something different on the fire—cleansing betony—and it flared, the light flashing off jewelry scattered on the dresser.

Deirdre’s belly did not stop moving with the room, however. She sat bolt upright, and Levarcham, now settled on the hearth-bench, shoved an empty pot at her with her foot. Deirdre’s mouth quirked and, grabbing it, she vomited up the dregs of the potion. The clenching of her stomach felt good, the violent retching emptying her of anything that was not the sensation of soaring. At last, she groped for a cloth and wiped her mouth, draining the last drops of water from the jug before slumping against a chair.

Her druid teacher was used to such travails and had swiftly regained her composure, only her slight pallor and labored breathing betraying her. She was frowning at Deirdre’s brow and, with a shaking finger, Deirdre touched her forehead, smearing the tip with blood.

Levarcham’s staff struck the floor. “What did I tell you, foolish girl?”

Deirdre dabbed at the blood with her sleeve. “Not to move my body.”

“It is only your spirit that you merge with the bird’s—you must keep your body still. And so? I feel you lose focus, and when I open my eyes there you are, waving your arms and launching yourself into the air!”

Deirdre bit her lip to stop that mental picture showing on her face. “Hmm.”

The staff cracked the floor again and Levarcham leaned over her crooked leg, all traces of the trance gone from her piercing gray eyes. “What if you fell hard and hurt yourself? Or rolled in the fire?”

Deirdre drew a steadying breath. “You have good reason to reprove me.” As Levarcham’s brows nearly disappeared into her hair, Deirdre smiled. “But, with respect, we could assume you already have and I’ve apologized profusely, so we can move on.” She clambered to her knees and hooked a finger around Levarcham’s, linking them as they had been in flight. “I felt the eagle this time.”

The expression on Levarcham’s long, stern face warred between pride and severity. She thinned her mouth toward the latter, squeezing Deirdre’s finger firmly before returning it to her. “There are three things I told you to do, one of which you obviously forgot. What are they?”

Deirdre gave in with a grin and sat cross-legged, palms up. “Strengthen the thread between body and spirit. Retain my own awareness. And keep my body still.”

“Exactly.” Levarcham gripped her staff with both hands, mollified. “It is the most demanding of druid skills and takes years of practice to achieve alone. We don’t fully understand how we do it at all, except that great discipline and a strong will are essential.” She snorted, her gaze sweeping Deirdre. “The will you have by the cartload. The other I’m still waiting on.”

Deirdre ignored that, the thrill of flight still lingering in her aching limbs. “I’m sure I felt the feathers move, and saw the mountains.” She arched an innocent brow. “You’re always telling me to notice details.”

Levarcham was silent for a long moment, and when she spoke again her voice was ominously quiet. “This is no idle trick. It is a sacred act to touch the spirit of another creature, let alone share its body. It should only be attempted after the proper prayers and fasting to lighten flesh and soul; the songs of honor and exhortations to the gods.” The druid’s stony face and crooked limp had always been daunting, her long, dark hair frosted over despite her only living for forty years. Her power was not in her lean body, however, but in her eyes, luminous as twilight on water. “You know I should not be teaching you any of this at all.” Those eyes darted away, hiding her thoughts. “I could be banished from my order and exiled from the king’s service altogether.”

Deirdre’s thrill faded. “I haven’t forgotten.” The idea of any harm coming to Levarcham or her foster parents, Fintan and Aiveen, was enough to sober her at once.

Levarcham stood, cupping Deirdre’s jaw. “But this is not about me. If the thread breaks, your soul will be lost and your body will perish.” Despite the fire, a shiver nipped all the way up Deirdre’s back. “You could die.”

“Then why show me?” All the ecstasy had flown from Deirdre and she hauled herself upright, still unsteady. At nearly eighteen, she had reached the same height as her teacher and they gazed at each other, breathing hard.

“I don’t entirely know. I felt I must—and the fact you have gained even a glimpse hints at some gift for it. Nevertheless, it’s serious—death is serious. The crossing into the Otherworld is no time for jests.”

“Perhaps it’s the best time for jests.” Deirdre couldn’t keep the fierceness from her voice. “I’d rather go boldly, anyway. At least the gods would know I’d lived.”

A shadow passed across Levarcham’s angular features. “Fledgling.” She reached out a finger again. Deirdre did the same. The tips touched, the younger woman smiling wryly. The druid limped to the door, her head brushing the sprays of rowan-berries over the lintel, the tiny, red fruits shriveled on the bough. “Bathe that wound and put a compress on it.” She braced herself visibly. “The king is coming from Emain Macha any day now. There is knitbone in my saddle pack that will help the bruise; I will have Aiveen pulp it in her mortar.”

Deirdre merely nodded, keeping her face still—something she had perfected with practice. It was a mask that stopped Levarcham, Fintan and Aiveen from hurting for her more than they already did.

After the druid left, she turned to the loom against the wall, threaded with an unfinished strip of cloth. Her hands gripped the oak beam, knuckles white, her head tilted so the long, golden strands of her hair mingled with the colored wool. The loose threads bled out at the bottom, unraveling as she was . . .

Lately the pressure inside had grown more potent, a force welling up that seemed too large for her body. Her skin felt stretched and thin, muscles straining to contain it. Levarcham said she was merely filling out since her moon-bleeding had at long last begun, but Deirdre knew it was something deeper.

What she felt herself to be wasn’t what they all saw: fair-haired, green-eyed, soft-skinned. She had never been that, even as a child. Then, her tiny world seemed like a vast adventure, and she gleefully embarked on all the journeys her imagination could conjure from three little huts, an encircling wall and a narrow valley. Oceans! Endless plains! Glittering caverns!

As she grew, she took to wandering the woods alone, for only in that silence could she hear the whisper of her emerging spirit, that glimmering promise of hidden depths beyond. She expanded and grew, but the valley did not, and wonder turned to frustration.

The whispers inside her turned into a murmuring sea, its secrets surging and ebbing before she could catch them. In desperation, she paced between the ash trees, walking in spirals that drew ever tighter. She stood with dew trickling down her brows and prayed that the bark would flow over her like a silvery skin so she could disappear. She crept into the boles of oaks, sank into leaf-mold, but she could not quiet that restless tide. All that happened in the expectant hush was that she heard her pulse, counting down the moments.

The king is coming.

She rested her forehead in her hands and let the room fall away, conjuring the image of an unfettered eagle against an endless sky.

PQ

The stag launched itself across the stream and landed with a stumble, before recovering and tearing up the bracken slope. Naisi saw the flash of its pale belly as it scrabbled through the brown ferns, dappled sun glinting on its antlers.

“Around this way!” Ardan hissed, thudding along behind his elder brother.

Naisi barely heard him, his pounding heart filled with the roar of the stream in the undergrowth before him. His thoughts raced along with the tumbling rapids. Could go around . . . shallow to the south . . . that will lose time . . . on the hill he’ll escape . . .

The ground dropped away into a ravine of churning water. Teetering on his heels, Naisi whipped the cocked arrow off his string and looped the bow over his back. “Naisi!” Ardan growled. “Don’t you dare . . .”

Naisi sized up the distance, gripped the arrow between his teeth and flung himself over the edge, hands outstretched. The gorge yawned below him, the foam only thinly veiling the teeth of the rocks.

His fingers caught a fallen oak leaning across the gap, its bark slippery with moss. Every muscle screamed as he wriggled his hands along, feet dangling over the drop. He swung a leg into a crevice of wet rocks, then levered himself on top of the trunk, standing up to balance precariously. Arms out, he danced a few wobbly steps between yellow-leaved branches, then threw himself up the steep bank.

“Ainnle,” Ardan bellowed, “we’ll circle around to the ford. Come on!”

His youngest brother’s voice floated to Naisi above the roaring of the stream. “I go where he goes.”

“You’ll snap every bone in your body if you fall.”

“See you on the other side!” Ainnle sang out.

Naisi wiped spray from his eyes and stuck the arrow in its quiver. He forced his straining legs up the slope, the dying bracken clinging to his calves in wet fronds. The hide of the deer had become lost amid the turning leaves of brown and gold, but he still felt confident they’d catch it. This one already trailed scarlet down its side from his first arrow, and it had landed badly, laming itself. Somewhere up there it must be slowing.

He reached a ragged escarpment and saw the ravine up which the stag must have leaped. The breakaway was filled with tumbled rock and tree roots and he stormed up it, scrabbling with bleeding palms and barked shins. The slope gave way to flatter ground scattered with boulders and scree, and he immediately spied the stag. It boasted only a few antler tines, and in its youth and inexperience had blundered into the rocks, snapping its leg.

Trotting forward, Naisi spat on his hand and wiped the blood down his hide trews, drawing out his throwing spear. He and his two brothers had devised the short hunting lance and the carrier that went across the back, so a man could run after game for days. The sons of Usnech did not stick to the safe, lowland trails, pursuing boar on horseback, only for hounds to bring them down.

Unlike some.

Naisi frowned and leaned on the spear, still panting, the cold breeze lifting his sweaty braids from his neck. The branches of an overhanging rowan scratched at the rocks, making the deer’s dark eyes roll at him in terror. He should finish it off. He lifted the spear, his arm fatigued from the chase.

All at once, the stag stopped struggling and merely lay there, its breath turning to mist on the crisp air. The spear remained hovering, and Naisi found himself rooted to the spot, unable to look away.

The deer’s red flanks were foamed with sweat, and the nostrils in its soft muzzle flexed and closed, pulsing in time with Naisi’s blood. His breath quickened as he watched its chest rising and falling, emitting puffs of vapor. It breathed in time with his heartbeat. The stag’s eye swiveled to fix on him, as if staring straight into his spirit. Its pupil was a pool drawing him in, the waters dissolving them so he was the stag and the stag was him . . .

Ainnle and Ardan came pounding up. “I don’t want to know how you got up that ravine so fast,” Ardan panted to Naisi.

“I nearly made it after him.” Ainnle flicked sweat from his thick, black hair. “Nearly.”

Naisi ignored them, locked in the communion with the stag. All the while he’d been running, the thrill of the chase had been swelling in his chest, but now it was collapsing, sinking in on itself. The stag strained against the rock and Naisi’s own leg cramped, shooting pain up his thigh. It was trapped. It had no way to run free now. Naisi mac Usnech, famed as a hunter, could not make the killing blow.

His middle brother, Ardan, hefted his spear. “It’s suffering.” He glanced at the youngest, Ainnle. “We normally have to rein you in. What are you waiting for?”

Ainnle’s green eyes were as always fixed on Naisi. “It’s his kill.”

The stag slumped against the boulder, and despair pooled in Naisi’s belly.

“If you won’t release it, I will,” Ardan declared, and then his spear was soaring through the air, embedding itself in the stag’s chest with a solid thunk. It was a thing of beauty, that throw: a perfect arc, a clean kill. Naisi tried to summon an old stab of pleasure, a heated thrill, but all he felt was coldness.

The beast stiffened when the point entered its body, its spine arching back before sagging. Naisi imagined its spirit being released, soft and light as smoke, while its ribs slackened and it spilled blood over the mossy rock. Only when its neck finally bowed could he breathe out. He clasped the hunt amulet strung at his neck, the tiny deer carved of antler browned by his touch. We honor your death, he said to the deer. They would feast on meat tonight, and tomorrow their own limbs would fill with strength. It was right and good, he told himself—and then told himself again.

“Gods,” Ardan exclaimed, bending over the downed beast. “What is that?”

He was peering at something Naisi hadn’t noticed because he thought it was blood: an arrowhead that had broken off in the stag’s rump and lodged under the skin. Faint shreds of scarlet-dyed threads trailed from it.

Ardan’s dark head dipped as he poked at the barb. Then his shoulders stiffened and when he looked up at his elder brother, his skin was blanched beneath the flush of exertion.

A pang hit Naisi’s heart. “What?”

Ardan swallowed. “It is the king’s mark.”

PUUQ

Leaf-fall

She was silver, an iridescence that arced along its trajectory like a falling star. The eagle hovered against the sky, wing-tips spread, and Deirdre imagined her spirit as a net that would capture it in a glittering sling of light.

Her body still lay in trance by the fire and she had to sum- mon immense focus to keep sending soul-breath along the thread that joined spirit and body. Now let the light sink in. It was Levarcham’s sibilant whisper, chanted into her ear. Her teacher’s will flowed beneath her, a current pushing her forward . . . upward.

The druid had fasted and sung with her for days, striking the drum until the sonorous pulse rang through both their bodies. Levarcham had endured the spasms and nausea of the herbs, all to fuse her energy with Deirdre and give her this fleeting chance of sacred flight.

The determination to stay focused on the soul-cord and the eagle at the same time was a keen pain, honed over moons of torturous practice. Deirdre was exhausted. It would be easier to fall back into her body. But she would not fail or waver.

Her own frustration had provided the force that initially flung her free, Levarcham’s will then lifting her, helping her break through the boundaries for one, long breath. There . . . She caught a flash of sensation: arms spread, a strange lightness of bones. The shock blanked her mind. Breathe, breathe! Levarcham urged.

Deirdre was gazing from other eyes. The rush of air peeled back wing-feathers and there was a blur of mountains, sunlight and shadow flitting across bare rock. At once, the eagle plunged into a dive and the land spun toward her. The bird opened its beak and screeched in ecstasy: freedom!

The one thing denied her. The one thing . . .

A resounding crash tore her from her trance.

She found herself sprawled in the rushes by an overturned stool with a jug glugging water into the rushes. A moment later, pain lanced her brow. “Deirdre!” Levarcham rasped, but she could not answer, clutching at the floor as it bucked beneath her, the walls of her little hut spinning.

The whirl of the room gradually slowed, and eventually lurched and stopped. A sense of her surroundings began to seep back in. Not air, not sun . . . but flickering light on curved mud walls and low thatch roof. Crackling flames drove the chill from the door-hide, and there was a lingering tang of herb smoke. Then Levarcham tossed something different on the fire—cleansing betony—and it flared, the light flashing off jewelry scattered on the dresser.

Deirdre’s belly did not stop moving with the room, however. She sat bolt upright, and Levarcham, now settled on the hearth-bench, shoved an empty pot at her with her foot. Deirdre’s mouth quirked and, grabbing it, she vomited up the dregs of the potion. The clenching of her stomach felt good, the violent retching emptying her of anything that was not the sensation of soaring. At last, she groped for a cloth and wiped her mouth, draining the last drops of water from the jug before slumping against a chair.

Her druid teacher was used to such travails and had swiftly regained her composure, only her slight pallor and labored breathing betraying her. She was frowning at Deirdre’s brow and, with a shaking finger, Deirdre touched her forehead, smearing the tip with blood.

Levarcham’s staff struck the floor. “What did I tell you, foolish girl?”

Deirdre dabbed at the blood with her sleeve. “Not to move my body.”

“It is only your spirit that you merge with the bird’s—you must keep your body still. And so? I feel you lose focus, and when I open my eyes there you are, waving your arms and launching yourself into the air!”

Deirdre bit her lip to stop that mental picture showing on her face. “Hmm.”

The staff cracked the floor again and Levarcham leaned over her crooked leg, all traces of the trance gone from her piercing gray eyes. “What if you fell hard and hurt yourself? Or rolled in the fire?”

Deirdre drew a steadying breath. “You have good reason to reprove me.” As Levarcham’s brows nearly disappeared into her hair, Deirdre smiled. “But, with respect, we could assume you already have and I’ve apologized profusely, so we can move on.” She clambered to her knees and hooked a finger around Levarcham’s, linking them as they had been in flight. “I felt the eagle this time.”

The expression on Levarcham’s long, stern face warred between pride and severity. She thinned her mouth toward the latter, squeezing Deirdre’s finger firmly before returning it to her. “There are three things I told you to do, one of which you obviously forgot. What are they?”

Deirdre gave in with a grin and sat cross-legged, palms up. “Strengthen the thread between body and spirit. Retain my own awareness. And keep my body still.”

“Exactly.” Levarcham gripped her staff with both hands, mollified. “It is the most demanding of druid skills and takes years of practice to achieve alone. We don’t fully understand how we do it at all, except that great discipline and a strong will are essential.” She snorted, her gaze sweeping Deirdre. “The will you have by the cartload. The other I’m still waiting on.”

Deirdre ignored that, the thrill of flight still lingering in her aching limbs. “I’m sure I felt the feathers move, and saw the mountains.” She arched an innocent brow. “You’re always telling me to notice details.”

Levarcham was silent for a long moment, and when she spoke again her voice was ominously quiet. “This is no idle trick. It is a sacred act to touch the spirit of another creature, let alone share its body. It should only be attempted after the proper prayers and fasting to lighten flesh and soul; the songs of honor and exhortations to the gods.” The druid’s stony face and crooked limp had always been daunting, her long, dark hair frosted over despite her only living for forty years. Her power was not in her lean body, however, but in her eyes, luminous as twilight on water. “You know I should not be teaching you any of this at all.” Those eyes darted away, hiding her thoughts. “I could be banished from my order and exiled from the king’s service altogether.”

Deirdre’s thrill faded. “I haven’t forgotten.” The idea of any harm coming to Levarcham or her foster parents, Fintan and Aiveen, was enough to sober her at once.

Levarcham stood, cupping Deirdre’s jaw. “But this is not about me. If the thread breaks, your soul will be lost and your body will perish.” Despite the fire, a shiver nipped all the way up Deirdre’s back. “You could die.”

“Then why show me?” All the ecstasy had flown from Deirdre and she hauled herself upright, still unsteady. At nearly eighteen, she had reached the same height as her teacher and they gazed at each other, breathing hard.

“I don’t entirely know. I felt I must—and the fact you have gained even a glimpse hints at some gift for it. Nevertheless, it’s serious—death is serious. The crossing into the Otherworld is no time for jests.”

“Perhaps it’s the best time for jests.” Deirdre couldn’t keep the fierceness from her voice. “I’d rather go boldly, anyway. At least the gods would know I’d lived.”

A shadow passed across Levarcham’s angular features. “Fledgling.” She reached out a finger again. Deirdre did the same. The tips touched, the younger woman smiling wryly. The druid limped to the door, her head brushing the sprays of rowan-berries over the lintel, the tiny, red fruits shriveled on the bough. “Bathe that wound and put a compress on it.” She braced herself visibly. “The king is coming from Emain Macha any day now. There is knitbone in my saddle pack that will help the bruise; I will have Aiveen pulp it in her mortar.”

Deirdre merely nodded, keeping her face still—something she had perfected with practice. It was a mask that stopped Levarcham, Fintan and Aiveen from hurting for her more than they already did.

After the druid left, she turned to the loom against the wall, threaded with an unfinished strip of cloth. Her hands gripped the oak beam, knuckles white, her head tilted so the long, golden strands of her hair mingled with the colored wool. The loose threads bled out at the bottom, unraveling as she was . . .

Lately the pressure inside had grown more potent, a force welling up that seemed too large for her body. Her skin felt stretched and thin, muscles straining to contain it. Levarcham said she was merely filling out since her moon-bleeding had at long last begun, but Deirdre knew it was something deeper.

What she felt herself to be wasn’t what they all saw: fair-haired, green-eyed, soft-skinned. She had never been that, even as a child. Then, her tiny world seemed like a vast adventure, and she gleefully embarked on all the journeys her imagination could conjure from three little huts, an encircling wall and a narrow valley. Oceans! Endless plains! Glittering caverns!

As she grew, she took to wandering the woods alone, for only in that silence could she hear the whisper of her emerging spirit, that glimmering promise of hidden depths beyond. She expanded and grew, but the valley did not, and wonder turned to frustration.

The whispers inside her turned into a murmuring sea, its secrets surging and ebbing before she could catch them. In desperation, she paced between the ash trees, walking in spirals that drew ever tighter. She stood with dew trickling down her brows and prayed that the bark would flow over her like a silvery skin so she could disappear. She crept into the boles of oaks, sank into leaf-mold, but she could not quiet that restless tide. All that happened in the expectant hush was that she heard her pulse, counting down the moments.

The king is coming.

She rested her forehead in her hands and let the room fall away, conjuring the image of an unfettered eagle against an endless sky.

PQ

The stag launched itself across the stream and landed with a stumble, before recovering and tearing up the bracken slope. Naisi saw the flash of its pale belly as it scrabbled through the brown ferns, dappled sun glinting on its antlers.

“Around this way!” Ardan hissed, thudding along behind his elder brother.

Naisi barely heard him, his pounding heart filled with the roar of the stream in the undergrowth before him. His thoughts raced along with the tumbling rapids. Could go around . . . shallow to the south . . . that will lose time . . . on the hill he’ll escape . . .

The ground dropped away into a ravine of churning water. Teetering on his heels, Naisi whipped the cocked arrow off his string and looped the bow over his back. “Naisi!” Ardan growled. “Don’t you dare . . .”

Naisi sized up the distance, gripped the arrow between his teeth and flung himself over the edge, hands outstretched. The gorge yawned below him, the foam only thinly veiling the teeth of the rocks.

His fingers caught a fallen oak leaning across the gap, its bark slippery with moss. Every muscle screamed as he wriggled his hands along, feet dangling over the drop. He swung a leg into a crevice of wet rocks, then levered himself on top of the trunk, standing up to balance precariously. Arms out, he danced a few wobbly steps between yellow-leaved branches, then threw himself up the steep bank.

“Ainnle,” Ardan bellowed, “we’ll circle around to the ford. Come on!”

His youngest brother’s voice floated to Naisi above the roaring of the stream. “I go where he goes.”

“You’ll snap every bone in your body if you fall.”

“See you on the other side!” Ainnle sang out.

Naisi wiped spray from his eyes and stuck the arrow in its quiver. He forced his straining legs up the slope, the dying bracken clinging to his calves in wet fronds. The hide of the deer had become lost amid the turning leaves of brown and gold, but he still felt confident they’d catch it. This one already trailed scarlet down its side from his first arrow, and it had landed badly, laming itself. Somewhere up there it must be slowing.

He reached a ragged escarpment and saw the ravine up which the stag must have leaped. The breakaway was filled with tumbled rock and tree roots and he stormed up it, scrabbling with bleeding palms and barked shins. The slope gave way to flatter ground scattered with boulders and scree, and he immediately spied the stag. It boasted only a few antler tines, and in its youth and inexperience had blundered into the rocks, snapping its leg.

Trotting forward, Naisi spat on his hand and wiped the blood down his hide trews, drawing out his throwing spear. He and his two brothers had devised the short hunting lance and the carrier that went across the back, so a man could run after game for days. The sons of Usnech did not stick to the safe, lowland trails, pursuing boar on horseback, only for hounds to bring them down.

Unlike some.

Naisi frowned and leaned on the spear, still panting, the cold breeze lifting his sweaty braids from his neck. The branches of an overhanging rowan scratched at the rocks, making the deer’s dark eyes roll at him in terror. He should finish it off. He lifted the spear, his arm fatigued from the chase.

All at once, the stag stopped struggling and merely lay there, its breath turning to mist on the crisp air. The spear remained hovering, and Naisi found himself rooted to the spot, unable to look away.

The deer’s red flanks were foamed with sweat, and the nostrils in its soft muzzle flexed and closed, pulsing in time with Naisi’s blood. His breath quickened as he watched its chest rising and falling, emitting puffs of vapor. It breathed in time with his heartbeat. The stag’s eye swiveled to fix on him, as if staring straight into his spirit. Its pupil was a pool drawing him in, the waters dissolving them so he was the stag and the stag was him . . .

Ainnle and Ardan came pounding up. “I don’t want to know how you got up that ravine so fast,” Ardan panted to Naisi.

“I nearly made it after him.” Ainnle flicked sweat from his thick, black hair. “Nearly.”

Naisi ignored them, locked in the communion with the stag. All the while he’d been running, the thrill of the chase had been swelling in his chest, but now it was collapsing, sinking in on itself. The stag strained against the rock and Naisi’s own leg cramped, shooting pain up his thigh. It was trapped. It had no way to run free now. Naisi mac Usnech, famed as a hunter, could not make the killing blow.

His middle brother, Ardan, hefted his spear. “It’s suffering.” He glanced at the youngest, Ainnle. “We normally have to rein you in. What are you waiting for?”

Ainnle’s green eyes were as always fixed on Naisi. “It’s his kill.”

The stag slumped against the boulder, and despair pooled in Naisi’s belly.

“If you won’t release it, I will,” Ardan declared, and then his spear was soaring through the air, embedding itself in the stag’s chest with a solid thunk. It was a thing of beauty, that throw: a perfect arc, a clean kill. Naisi tried to summon an old stab of pleasure, a heated thrill, but all he felt was coldness.

The beast stiffened when the point entered its body, its spine arching back before sagging. Naisi imagined its spirit being released, soft and light as smoke, while its ribs slackened and it spilled blood over the mossy rock. Only when its neck finally bowed could he breathe out. He clasped the hunt amulet strung at his neck, the tiny deer carved of antler browned by his touch. We honor your death, he said to the deer. They would feast on meat tonight, and tomorrow their own limbs would fill with strength. It was right and good, he told himself—and then told himself again.

“Gods,” Ardan exclaimed, bending over the downed beast. “What is that?”

He was peering at something Naisi hadn’t noticed because he thought it was blood: an arrowhead that had broken off in the stag’s rump and lodged under the skin. Faint shreds of scarlet-dyed threads trailed from it.

Ardan’s dark head dipped as he poked at the barb. Then his shoulders stiffened and when he looked up at his elder brother, his skin was blanched beneath the flush of exertion.

A pang hit Naisi’s heart. “What?”

Ardan swallowed. “It is the king’s mark.”

Recenzii

"In this graceful retelling of the Irish legend of Deirdre of the Sorrows, the young woman whose birth laid a curse upon the kingdom of Ulster and its aging king, Conor, the author of The White Mare captures the sense of tragedy, nobility, and the acceptance of destiny that permeates Celtic myth. Watson's characters have both a larger-than-life appeal and a commonality that emphasizes their human frailty as well as their dedication to life and love."—Library Journal

“Wonderful. Watson does not tell the story, she lives it. Mystical and poetic, a tour de force. A magical and compelling recreation of the lost Celtic world.”—Rosalind Miles, author of Isolde, queen of the Western Isles

“Jules Watson has conjured up the mythic past, a land of Celtic legend and stark grandeur. Readers will find her world and characters fascinating and unforgettable.”—Sharon K. Penman, author of Dragon’s Lair

“Wonderful. Watson does not tell the story, she lives it. Mystical and poetic, a tour de force. A magical and compelling recreation of the lost Celtic world.”—Rosalind Miles, author of Isolde, queen of the Western Isles

“Jules Watson has conjured up the mythic past, a land of Celtic legend and stark grandeur. Readers will find her world and characters fascinating and unforgettable.”—Sharon K. Penman, author of Dragon’s Lair

Descriere

Celtic historical author Watson takes on the story of Deirdre--the Irish Helen of Troy--in a tale that is at once lushly romantic, magical, and tragic, in this first of a linked pair of novels about Ireland's most famous women.