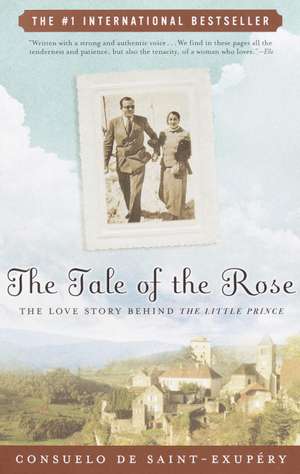

The Tale of the Rose: The Love Story Behind the Little Prince

Autor Consuelo De Saint-Exupery, Consuelo de Saint-Exuperyen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 dec 2002

Their love affair and marriage would take them from Buenos Aires to Paris to Casablanca to New York. It would take them through periods of betrayal and infidelity, pain and intense passion, devastating abandonment and tender, poetic love. The Tale of the Rose is the story of a man of extravagant dreams and of the woman who was his muse, the inspiration for the Little Prince’s beloved rose—unique in all the world—whom he could not live with and could not live without.

Preț: 114.60 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 172

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.93€ • 22.90$ • 18.11£

21.93€ • 22.90$ • 18.11£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 25 martie-08 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780812967173

ISBN-10: 0812967178

Pagini: 352

Ilustrații: 16-PAGE PHOTO INSERT

Dimensiuni: 134 x 204 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

ISBN-10: 0812967178

Pagini: 352

Ilustrații: 16-PAGE PHOTO INSERT

Dimensiuni: 134 x 204 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

Notă biografică

Consuelo de Saint-Exupery wrote The Tale of the Rose in 1945, with the pain of loss still fresh in her heart. The manuscript was sealed away in a locked trunk on her estate, and found by chance, fifteen years after her death, when an academic was digging around for fresh material for a new biography of Saint-Exupery. He died in 1979 and left her estate, and the proceeds from her share of The Little Prince to her gardener.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Chapter 1

Every morning on the bridge, Ricardo Viñes, the pianist with hands like a dove's wings, would say in my ear, "Consuelo, you are not a woman."

I would laugh and kiss his cheeks, pushing back his long mustache that sometimes made me sneeze. He would then go through all the rituals of Spanish courtesy, wishing me a good morning, inquiring about my dreams, inviting me to enjoy this new day of our journey to Buenos Aires. And every day I wondered what Don Ricardo could possibly mean by his little morning greeting.

"Am I an angel, then? An animal? Do I not exist?" I asked him fiercely at last.

He fell serious and turned that El Greco face of his out toward the sea a few moments, then took my hands in his.

"So, child, you know how to listen; that is good. . . . For as long as we have been on this ship, I have been wondering what you are. I know I like what is within you, but I also know that you are not a woman. I have spent whole nights thinking about it, and finally I set to work. I am more of a composer than a pianist, and only in music can I express the way I sense it, this thing that you are."

With the Castilian elegance for which he was so famous in Europe, he raised the lid of the piano in the ship's lounge. I listened. The piece he played was very beautiful. The ocean rocked us gently, prolonging the music, and then, as usual, we started telling each other about our sleepless nights and latest sightings on the horizon, for every so often the sea would yield a glimpse of a lighthouse, an island, or another boat.

I thought Viñes's little greeting would never bother me again, now that it had been expressed in music, and I went to join the other passengers on board the Massilia.

There were Europeans on the ship, whose travel agents had persuaded them that the whole young American continent would reveal itself to them in the sound of a tango. And there were South American tourists, coming home from Paris with a sizable booty of dresses, perfumes, jewels, and bons mots. The older women talked freely and openly about all the pounds they'd taken off at their spas. Other women, even more brazen, showed me photographs in which the various surgical phases of their pretty little noses could be measured to the millimeter. A gentleman whispered to me about the success of a delicate operation: a dental transplant, using teeth bought on the cheap from people with no money.

The younger women made a game of appearing in four or five different dresses every day. They had to get some wear out of those dresses, for the South American customs officers were very hard on the practice, common among society women, of smuggling luxury items back from Europe. Between each new outfit they would douse themselves in heady perfumes. The Argentine and Brazilian women far outstripped the Europeans in the luxury of their attire. And they were always ready to play the guitar or sing the traditional songs of their countries at the drop of a hat. As the boat progressed, these daughters of the tropics began behaving more naturally and their distinctive character grew more conspicuous. Old and young alike, they twittered away in Portuguese and Spanish without giving the French women a chance to slip in even the briefest anecdote.

Rita, a young Brazilian, had discovered a way of making her guitar sound like a church bell ringing for mass or a carillon chiming from a campanile. She said she had first been inspired to do this during a Brazilian carnival, one of those nights of Negro sorcerers and Indians when women abandon themselves to their desires, their truth, the whole vast life of the trackless, virgin jungle. Rita's bells sometimes fooled the other passengers and brought them out onto the bridge. She claimed her guitar was a magical object and said she thought she would die if any harm ever came to it. Père Landhe, the priest she often confided in, was thoroughly disarmed by her and finally gave up lecturing her about her pagan desires and magical beliefs.

I liked Père Landhe. We would take long strolls together, talking about life, God, the problems of the heart, and how to become a better person. When he asked why I never appeared in the dining room, I told him I was in mourning for my husband, Enrique Gómez Carrillo,* and that I was making this journey at the invitation of the Argentine government, which my poor late husband, a diplomat, had represented in Europe for a time. Père Landhe, who was well acquainted with several of my late husband's books, did his best to console me; he listened while I told him, with all the sincerity of my youth, about the love a fifty-year-old man had awoken in me during the all-too-brief time of our marriage. I had inherited all his books, his name, his fortune, and several newspapers he had owned. A life, his life, had been entrusted to me, and I wanted to understand it, relive it, and go on with my own life in homage to his memory. I wanted to grow for him alone; that gift to him was my mission.

Ricardo Viñes had been one of my husband's close friends. Don Ricardo had paid special attention to me in Paris because, through my mother, I bore the same name as one of his friends, the Marquis de Sandoval, and for Viñes, Sandoval meant storms, the ocean, an unfettered life, and memories of the great conquistadors. Every woman in Paris adored him, but he was an ascetic—his greatest love affairs had never been anything more than musical. One day we heard Rita, the guitarist, say to him in a low, husky voice, "Is it true you belong to a very strict, secret order, even more severe than the Jesuits, a sect that requires you to devote yourself exclusively to art?"

"Of course," he replied. "Have you heard, as well, that we shave off half our mustaches on nights when the moon is full, and they grow back instantly?"

My other chaperone on that ocean liner was Benjamin Crémieux, who was going to Buenos Aires to deliver a series of lectures. He had the face of a rabbi, and there was fire in his gaze and warmth in his voice. His words, I felt, were charged with a secret power that reassured me.

"When you're not laughing, your hair grows sad," he told me. "Your hair tires out quicker than anything else about you. Your curls droop like sleepy children. It's curious: when you light up and start telling stories about magic and circuses and the volcanoes in El Salvador, your hair comes alive again, too. If you want to be beautiful, you must always laugh. Promise me that tonight you won't let your hair fall asleep."

He spoke to me as if I were a butterfly that he was asking to hold its wings open wide so he could have a better view of their colors. Despite the long, threadbare jacket he always wore and his beard, which made him look very serious, he was the youngest of my friends. His Jewish blood was pure and just. He seemed happy to be himself, to live his own life. He said he loved me because I knew how to transform myself into something new at every hour of the day. I didn't feel particularly flattered by this; I would have preferred to be like him, stable and contented with what God and nature had allowed me to be.

By the end of the voyage, Viñes, Crémieux, and I had become inseparable.

On the night before our arrival in Buenos Aires, very late, Don Ricardo played a strange and brilliant prelude, then announced that it was titled "La niña del Massilia."

"That is you," he said, holding the sheets of music out to me. "You are la niña, the little girl, on this ship."

Rita immediately wanted to play the piece with him on her guitar, for only her guitar, she said, could reveal the true meaning of the music, and of what Viñes had sensed in me.

When we docked, caught up in the feverish activity of landing, we were like automatons, hardly speaking to one another except out of politeness. Then I heard someone shouting on the bridge: "Where is the widow of Gómez Carrillo? ¿Dónde está la viuda de Gómez Carrillo?"

Only with an effort did I realize they were calling for me. "Señores, I am she," I murmured timidly.

"Oh! We thought you'd be an old lady!"

"I am what I can be," I said, as cameras flashed all around me. "Could you please direct me to a hotel?"

They thought I was joking. A government minister had come to the dock to welcome me. He announced that I was the guest of the Argentine government and that I would be staying at the Hotel España, the residence of official guests. The president apologized for not receiving me at his home, but he was much occupied with a pending revolution.

"What? A revolution?"

"Yes, madame, and a real one. But he is wise, Don El Peludo, this is his third term in office. He knows how to handle this type of incident."

"Will it happen soon, your revolution? Do you often have revolutions in this country?"

"We haven't had one for quite some time now. They say this one will take place on Wednesday."

"Is there no way of preventing it?"

"No," the minister answered, "I don't think so. The president doesn't want to have anything to do with it. He's waiting calmly for the revolution to come to him. He refuses to take any measure against the students who are demonstrating in the street, shouting 'Down with El Peludo.' The situation is serious, but I'm happy that you still have several days ahead of you in which to pay a visit to the president. I would advise you to go and see him tomorrow morning. He was very fond of your husband and will be happy to talk about him with his widow."

From the Hardcover edition.

Every morning on the bridge, Ricardo Viñes, the pianist with hands like a dove's wings, would say in my ear, "Consuelo, you are not a woman."

I would laugh and kiss his cheeks, pushing back his long mustache that sometimes made me sneeze. He would then go through all the rituals of Spanish courtesy, wishing me a good morning, inquiring about my dreams, inviting me to enjoy this new day of our journey to Buenos Aires. And every day I wondered what Don Ricardo could possibly mean by his little morning greeting.

"Am I an angel, then? An animal? Do I not exist?" I asked him fiercely at last.

He fell serious and turned that El Greco face of his out toward the sea a few moments, then took my hands in his.

"So, child, you know how to listen; that is good. . . . For as long as we have been on this ship, I have been wondering what you are. I know I like what is within you, but I also know that you are not a woman. I have spent whole nights thinking about it, and finally I set to work. I am more of a composer than a pianist, and only in music can I express the way I sense it, this thing that you are."

With the Castilian elegance for which he was so famous in Europe, he raised the lid of the piano in the ship's lounge. I listened. The piece he played was very beautiful. The ocean rocked us gently, prolonging the music, and then, as usual, we started telling each other about our sleepless nights and latest sightings on the horizon, for every so often the sea would yield a glimpse of a lighthouse, an island, or another boat.

I thought Viñes's little greeting would never bother me again, now that it had been expressed in music, and I went to join the other passengers on board the Massilia.

There were Europeans on the ship, whose travel agents had persuaded them that the whole young American continent would reveal itself to them in the sound of a tango. And there were South American tourists, coming home from Paris with a sizable booty of dresses, perfumes, jewels, and bons mots. The older women talked freely and openly about all the pounds they'd taken off at their spas. Other women, even more brazen, showed me photographs in which the various surgical phases of their pretty little noses could be measured to the millimeter. A gentleman whispered to me about the success of a delicate operation: a dental transplant, using teeth bought on the cheap from people with no money.

The younger women made a game of appearing in four or five different dresses every day. They had to get some wear out of those dresses, for the South American customs officers were very hard on the practice, common among society women, of smuggling luxury items back from Europe. Between each new outfit they would douse themselves in heady perfumes. The Argentine and Brazilian women far outstripped the Europeans in the luxury of their attire. And they were always ready to play the guitar or sing the traditional songs of their countries at the drop of a hat. As the boat progressed, these daughters of the tropics began behaving more naturally and their distinctive character grew more conspicuous. Old and young alike, they twittered away in Portuguese and Spanish without giving the French women a chance to slip in even the briefest anecdote.

Rita, a young Brazilian, had discovered a way of making her guitar sound like a church bell ringing for mass or a carillon chiming from a campanile. She said she had first been inspired to do this during a Brazilian carnival, one of those nights of Negro sorcerers and Indians when women abandon themselves to their desires, their truth, the whole vast life of the trackless, virgin jungle. Rita's bells sometimes fooled the other passengers and brought them out onto the bridge. She claimed her guitar was a magical object and said she thought she would die if any harm ever came to it. Père Landhe, the priest she often confided in, was thoroughly disarmed by her and finally gave up lecturing her about her pagan desires and magical beliefs.

I liked Père Landhe. We would take long strolls together, talking about life, God, the problems of the heart, and how to become a better person. When he asked why I never appeared in the dining room, I told him I was in mourning for my husband, Enrique Gómez Carrillo,* and that I was making this journey at the invitation of the Argentine government, which my poor late husband, a diplomat, had represented in Europe for a time. Père Landhe, who was well acquainted with several of my late husband's books, did his best to console me; he listened while I told him, with all the sincerity of my youth, about the love a fifty-year-old man had awoken in me during the all-too-brief time of our marriage. I had inherited all his books, his name, his fortune, and several newspapers he had owned. A life, his life, had been entrusted to me, and I wanted to understand it, relive it, and go on with my own life in homage to his memory. I wanted to grow for him alone; that gift to him was my mission.

Ricardo Viñes had been one of my husband's close friends. Don Ricardo had paid special attention to me in Paris because, through my mother, I bore the same name as one of his friends, the Marquis de Sandoval, and for Viñes, Sandoval meant storms, the ocean, an unfettered life, and memories of the great conquistadors. Every woman in Paris adored him, but he was an ascetic—his greatest love affairs had never been anything more than musical. One day we heard Rita, the guitarist, say to him in a low, husky voice, "Is it true you belong to a very strict, secret order, even more severe than the Jesuits, a sect that requires you to devote yourself exclusively to art?"

"Of course," he replied. "Have you heard, as well, that we shave off half our mustaches on nights when the moon is full, and they grow back instantly?"

My other chaperone on that ocean liner was Benjamin Crémieux, who was going to Buenos Aires to deliver a series of lectures. He had the face of a rabbi, and there was fire in his gaze and warmth in his voice. His words, I felt, were charged with a secret power that reassured me.

"When you're not laughing, your hair grows sad," he told me. "Your hair tires out quicker than anything else about you. Your curls droop like sleepy children. It's curious: when you light up and start telling stories about magic and circuses and the volcanoes in El Salvador, your hair comes alive again, too. If you want to be beautiful, you must always laugh. Promise me that tonight you won't let your hair fall asleep."

He spoke to me as if I were a butterfly that he was asking to hold its wings open wide so he could have a better view of their colors. Despite the long, threadbare jacket he always wore and his beard, which made him look very serious, he was the youngest of my friends. His Jewish blood was pure and just. He seemed happy to be himself, to live his own life. He said he loved me because I knew how to transform myself into something new at every hour of the day. I didn't feel particularly flattered by this; I would have preferred to be like him, stable and contented with what God and nature had allowed me to be.

By the end of the voyage, Viñes, Crémieux, and I had become inseparable.

On the night before our arrival in Buenos Aires, very late, Don Ricardo played a strange and brilliant prelude, then announced that it was titled "La niña del Massilia."

"That is you," he said, holding the sheets of music out to me. "You are la niña, the little girl, on this ship."

Rita immediately wanted to play the piece with him on her guitar, for only her guitar, she said, could reveal the true meaning of the music, and of what Viñes had sensed in me.

When we docked, caught up in the feverish activity of landing, we were like automatons, hardly speaking to one another except out of politeness. Then I heard someone shouting on the bridge: "Where is the widow of Gómez Carrillo? ¿Dónde está la viuda de Gómez Carrillo?"

Only with an effort did I realize they were calling for me. "Señores, I am she," I murmured timidly.

"Oh! We thought you'd be an old lady!"

"I am what I can be," I said, as cameras flashed all around me. "Could you please direct me to a hotel?"

They thought I was joking. A government minister had come to the dock to welcome me. He announced that I was the guest of the Argentine government and that I would be staying at the Hotel España, the residence of official guests. The president apologized for not receiving me at his home, but he was much occupied with a pending revolution.

"What? A revolution?"

"Yes, madame, and a real one. But he is wise, Don El Peludo, this is his third term in office. He knows how to handle this type of incident."

"Will it happen soon, your revolution? Do you often have revolutions in this country?"

"We haven't had one for quite some time now. They say this one will take place on Wednesday."

"Is there no way of preventing it?"

"No," the minister answered, "I don't think so. The president doesn't want to have anything to do with it. He's waiting calmly for the revolution to come to him. He refuses to take any measure against the students who are demonstrating in the street, shouting 'Down with El Peludo.' The situation is serious, but I'm happy that you still have several days ahead of you in which to pay a visit to the president. I would advise you to go and see him tomorrow morning. He was very fond of your husband and will be happy to talk about him with his widow."

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Written with a strong and authentic voice...We find in these pages all the tenderness and patience, but also the tenacity, of a woman who loves.”

—Elle

“Antoine de Saint-Exupéry wrote The Little Prince, inspired by a formidable princess called Consuelo. The drama and passionate romance sublimated beneath the children’s fairy tale is here, revealed in her memoir. What a life!”

—Isaac Mizrahi

“A poetic memoir of their tempestuous marriage...Consuelo...writes, with style and courage, for grown-ups.”

—Entertainment Weekly

“In pages weighty with love, passion, betrayal and tragedy, the Salvadoran-born beauty has reclaimed her place in the Saint-Exupéry myth.”

—The New York Times

—Elle

“Antoine de Saint-Exupéry wrote The Little Prince, inspired by a formidable princess called Consuelo. The drama and passionate romance sublimated beneath the children’s fairy tale is here, revealed in her memoir. What a life!”

—Isaac Mizrahi

“A poetic memoir of their tempestuous marriage...Consuelo...writes, with style and courage, for grown-ups.”

—Entertainment Weekly

“In pages weighty with love, passion, betrayal and tragedy, the Salvadoran-born beauty has reclaimed her place in the Saint-Exupéry myth.”

—The New York Times

Descriere

The newly discovered memoir of the passionate romance that inspired "The Little Prince" has been an international sensation translated into 17 languages--Consuelo de Saint-Exupery's love letter she could never send to her husband, written on Long Island in 1945 when the pain of his death was still fresh in her heart.