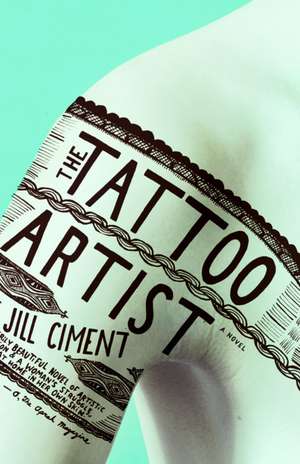

The Tattoo Artist

Autor Jill Cimenten Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 sep 2006

Flashback: it’s 1918 and Sara, a shop girl and aspiring artist, meets Philip, a wealthy member of the avant-garde elite. The two fall in love, marry, and collaborate to make art, surrounded by socialites and revolutionaries–until the Depression cripples not just Sara and Philip, but most of their patrons. When Philip is offered a job gathering masks from the South Seas, they jump at a chance to escape America’s sorrows, traveling to Ta’un’uu for what they think will be a week’s stay.

The rest is history–a history Sara records on her skin through the traditional tattoos that become her masterpiece and provide an accounting of her days. Narrated in vivid and starkly moving prose, The Tattoo Artist reminds us of the unforeseeable forces that shape each human life.

Preț: 101.99 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 153

Preț estimativ în valută:

19.52€ • 20.30$ • 16.11£

19.52€ • 20.30$ • 16.11£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 22 martie-05 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400078448

ISBN-10: 140007844X

Pagini: 207

Dimensiuni: 132 x 203 x 14 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 140007844X

Pagini: 207

Dimensiuni: 132 x 203 x 14 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Notă biografică

Jill Ciment was born in Montreal, Canada. Her books include two novels, Teeth of the Dog and The Law of Falling Bodies; a collection of short stories, Small Claims; and a memoir, Half a Life. She has been awarded two New York State Foundation for the Arts Fellowships and a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship. Ciment is a professor of English at the University of Florida. She lives in Gainesville, Florida.

Extras

CHAPTER ONE

I was born in 1902 on the Lower East Side, that open sore on the hip of Manhattan. My parents had immigrated to America the year before from a shtetl outside Warsaw. The Ta'un'uuans have taught me, however, that a journey never begins at the point of departure, but at the point of origin, and so I envision my parents, neither taller than five feet, my father's face bewildered and terrified, my mother's, arrogant and terrified, fleeing the pogroms of Russia for the pogroms of Rumania, Rumania for Budapest, Budapest for Warsaw, Warsaw for Antwerp, and finally arriving at a cold-water flat on the Lower East Side. My parents were not only exhausted by the journey, they were stupefied. In the end, the only question that truly preoccupied them was one that, in my bohemian youth, I dismissed as greenhorn sentimentality, and now, in old age, is the only question I, myself, ask: Where is home, and how do I get there?

Like the children of most fresh-off-the-boat Jews, I attended the only school my parents could comprehend, let alone afford: a landsman's quasi Hebrew school conducted in a cellar and lorded over by a succession of rod-wielding, self-appointed rabbis. My education consisted primarily of chanting Hebrew songs without having the least notion of, or reverence for, what I was singing.

The islanders believe that language originates in song, and that the human throat is a musical instrument, a flute of flesh and blood, and that the breath reverberating through the flute is the soul, and that the music emerging from the flute is the spirit.

Aside from a few deeply ingrained Hebrew songs, everything else has been lost to me from those years. I have, after all, been gone so long. The only keepsake I have is an ancient newspaper clipping, a gift from the archivist at the Yiddish Library who'd read about me in Life: it's a 1916 "Bintel Brief," the advice column of the Jewish Daily Forward, in which a letter of my father's was printed.

Dear Esteemed Editor,

I hope you will advise me in my present difficulty. I come from a small town in Russia, where, until I was twenty, I studied the Torah, but when I came to America, I quickly changed. I was influenced by progressive newspapers, and became a freethinker and a socialist. But the nature of my feelings is remarkable.

Listen to me: every year when the month of Elul rolls around, when the time of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur approaches, a melancholy begins to eat at my heart, like rust eats iron. When I go past a synagogue during those days and hear the cantor singing, my yearning becomes so great I cannot endure it. I see before me the small town, the fields, the little pond, the yeshiva. I recall my childhood friends and our sweet childlike faith. My heart constricts, and I run like a madman till the tears stream from my eyes and I become calmer.

Lately, I have returned to synagogue, despite the scorn of my freethinker daughter. I go not to pray to God, but to hear and refresh my aching soul with the cantor's melodies. I forget my unhappy weekday life, the dirty shop, my boss, the bloodsucker. All of America with its hurry-up life is forgotten.

What is your opinion of this? Are there others like me whose natures are such that memories of their childhood songs are sometimes stronger than their convictions? I await your answer.

Respectfully yours,

Benjamin Rabinowitz

I offer you my father's letter not to woo you with nostalgia, but because if there were an untouched square of skin left on my body, I would engrave it on my flesh.

Jewish law forbids tattooing: Thou shall not make in thy flesh a scratch over the soul. But what if the Ta'un'uuans are right, and the soul is breath? Then aren't the scratches left on my soul by my needles really just the moments when my breath caught, my voice cracked, unable to find song?

By sixteen, I had become, in my father's words, a freethinker, and by my own definition, a bohemian and an anarchist, a girl for whom religion and its trappings were irrelevant. To bring the point home to my parents, I would invariably light my after-dinner cigarette in the flame of the Sabbath candles.

I was a seamstress by day, a waist maker, the eighteenth girl in a row of twenty at the windowless end of the warehouse. Shopgirls worked their way toward the light by seniority. By week's end, my fingers would be so scratched and marred by the needles that one can't attribute all the abrasions on my soul to the tattoos. But on Saturday nights, I'd don my shopgirl's version of bohemian--a felt hat with purple plumage, a Gypsy skirt, and two immoral shanks of red stocking. My destination was Greenwich Village. The cultural gulf between the Lower East Side and Washington Square was probably greater than the one my parents had encountered when they left the steppes of Russia for Avenue D. At best, I'd covet a bench at the base of Stanford White's arch, sharing cigarettes with versions of myself, gaudily feathered shopgirls in whose discontented stares one could just make out little compressed diamonds of ambition. At worst, I'd wander the square by myself, catching glimpses of what anyone could plainly see were the real bohemians--paint-splattered artists, mustachioed socialists, regal-necked poetesses arguing away while ash spilled from the gold tips of their cigarette holders. The schism between them and me in my red stockings and cheap plumage, seemed as impossible to surmount as that between the gods and man.

For shopgirls like me, East Side Jews who spoke with guttural accents, the only lifeline out of workaday hell was the Educational Alliance, the center of Yiddish intelligentsia, a curious mix of night school, public forum, gymnasium, and revolutionary cells. The center had been a gift from a few philanthropic German Jews to their hardscrabble East European brethren. Sunday afternoons, young Zionists who could barely remember to water their mothers' rubber plants took to the stage to call for the transformation of an arid desert into a Jewish Eden. Ex-yeshiva shopboys, for whom the threading of a sewing machine was a daunting task, called for a futuristic mechanized utopia on earth.

My union, the Ladies' Waist Makers' Union, bought blocks of tickets for the Alliance's Sunday night lecture series: "Jews and the Graven Image"; "Is Marxism Scientific?"; "Revolution: If Not Now, When? If Not Us, Who?"; "The Jewish Themes of Ibsen."

One evening, an artist, an American Jew who had been educated in Zurich and Berlin, who had lived in Paris and Moscow, who spoke with intimacy about Picasso, Freud, and Trotsky as I might gossip about the girl at the next sewing machine, addressed us waist makers, and the boys from the Buttonhole Makers' and Collar Makers' unions, on the twentieth-century collision between art, the subconscious, and revolution.

A giant of a man, he had to stoop to reach the lectern. He had shoulder-length blond hair that he tossed to make his points. In a buckskin jacket and red silk vest, he dressed, to my mind at least, like a cross between Buffalo Bill and what I assumed was a Parisian painter. He told us that the art of the future would be made by the proletariat, workers just like us, then described the squalor of our shop life in enough glorious abstraction that it actually seemed possible. He explained how our subconscious, the antechamber of our unconscious, held within its misty foyer all the symbols we'd ever need. He urged us to have faith that art, with its noble and redemptive powers, would use those symbols to provide our beleaguered souls with the metaphors by which we could transform our misery into meaning. And when the time was right, he insisted that art would even spur us into revolution.

Did I believe him? A ragtag army of seamstresses and ex-yeshiva buchers advancing on Park Avenue brandishing needles and Symbolist paintings? What was the alternative? Fifty more years at a sewing machine? A tiny air shaft apartment facing a teenier one, my only view my neighbor's life? Whimpers, moans, hacks, grunts, fits of coughing, fits of prayer resounding through the thin walls? On the Lower East Side, the unconscious was not the symbol-laden fog of Freud and art. The unconscious was sleep or, if it lasted long enough, death.

Whatever doubts I had about his lecture I quickly quashed, as one might instinctively step on a dark shape in the periphery of one's vision.

When he climbed off the podium, I and a dozen other shopgirls surrounded him. He glanced down at us with bemused curiosity and teased us that his lecture would be followed by an impromptu quiz. He reached into the fringed pocket of his jacket and plucked out a gold cigarette case. Tapping his thumbnail on the tooled casing, he asked if any of us ladies would like to try a French cigarette? I was the only one to accept. I leaned into his lit match as defiantly as I leaned into the Sabbath flame. The rumor was that when he'd lectured at the Alliance the year before, he'd bedded only the prettiest of his admirers, comely girls with dreams as fragile as soap bubbles, girls who giggled at his rarefied allusions as others might nervously guffaw at a funeral. I wasn't particularly pretty, and I never giggled.

It would be easy to pretend that after thirty years among the islanders with their forthright sexuality, their worship of the body, I've lost all tolerance for the curtsies and bows, the feints and feigns of Western courtship. But even as a young woman, I detested coyness. Suffice it to say, when the other girls dispersed, it was I who followed him home, and I who seduced Philip.

His portrait graces my left breast. It is the first tattoo I engraved on myself. The portrait, however, in no way resembles the face I kissed that night; an unlined, untested face of cavalier certitude that the future would be as easy to read as a palm. The face on my left breast is desecrated, pillaged of all illusions, and though it breaks my heart to admit it, it is also the weakest part of my design--the point on my flesh where my emotions exceeded my skill--and no amount of virtuosity can disguise that weakness. The face on my left breast is a living death mask, as far removed from the young Philip as I am from the girl I was.

He lived in a refurbished livery stable on Washington Mews, refurbished with Carrara marble, Art Nouveau windows, Persian carpets, a Brancusi bronze, a gilt-framed Gauguin, and a collection of South Pacific masks. I was so ill educated, I didn't even know enough to be impressed. I thought the masks were examples of modern art. I walked up to the Gauguin and asked if Philip had painted it. When he laughed and shook his head, his hair whipped against his throat. I was too embarrassed to ask anything else. Just to end my ungainly silence, I unbuttoned my blouse and put my own collateral on display. I could see how amused he was by my brazenness. I was hardly amused; I was astounded by my daring. I let him finish the job, undoing the buttons, eyelets, hooks, and laces that confined me. I was and I wasn't a virgin. I'd had rudimentary sex the month before with a buttonhole maker on the Alliance's tar roof. Afterward, the boy and I declared ourselves freethinkers and never spoke to each other again.

Philip made love to me on his Hindoo blue settee. A practiced and precise lover, he believed his sojourns into the subconscious, his experiments with what he called "Surrealism," had led him to new levels of sensuality. I was hardly prepared to be the judge of that. I was still learning how to kiss.

I stayed with Philip for three nights and two days. He introduced me to the practice of automatic drawing after sex. With him, I tasted my first glass of champagne, my first bite of trayf. But what impressed me most, what trumps all my other memories despite half a century, is that Philip owned a telephone, an elegant black instrument on a fluted pedestal. I'd never seen one in a private house before. Whenever it rang, Philip grew exasperated, but I felt we were at the center of the world.

When I finally returned home, my frantic mother demanded to know where I'd been, and when I shamelessly told her, she called me a nafka, a whore, and wouldn't speak to me. The logistics of our not talking in a two-room tenement were complex. We had to steal past each other without so much as our breaths mingling. I had to bear witness to her mumbled quips without so much as a snipe back. Only my father, who had begun residing more and more in the bucolic fantasy of his Russian childhood, would speak to me. And only when my mother wasn't home.

"Sara, do you see that wall?" He had taken to believing that not only our tenement, but the sweatshop, his boss, all of America with its hurry-up life, was only a figment of his dreams. "That wall isn't a wall. That wall is the inside of my coffin." He took out his tefillin and prayer shawl, then kissed my cheek. "But you're not to worry, mein kint, I'll soon wake up."

I packed what little I had and left him davening toward the east, an air shaft strung with laundry, singing what must be the most heartrending of prayers, "Thank you God for returning to me my soul, which was in Your keeping."

I found lodging with six Litvak sisters from my union in a cellar apartment on Ludlow Street. My bed was the board that covered the kitchen tub. All night long, directly under my ear, the faucet leaked in fits and dribbles. My dreams sputtered and raced in time to that watery metronome, save for the nights that I slept beside Philip.

I wasn't his only lover: he made that unequivocally clear. He also made the conditions of my spending the night in his bed as complicated as a wedding contract. I couldn't stay for more than three consecutive nights. I couldn't keep any of my possessions in his closets or drawers. I was never to answer the telephone, though when it trilled, I pined to.

I was born in 1902 on the Lower East Side, that open sore on the hip of Manhattan. My parents had immigrated to America the year before from a shtetl outside Warsaw. The Ta'un'uuans have taught me, however, that a journey never begins at the point of departure, but at the point of origin, and so I envision my parents, neither taller than five feet, my father's face bewildered and terrified, my mother's, arrogant and terrified, fleeing the pogroms of Russia for the pogroms of Rumania, Rumania for Budapest, Budapest for Warsaw, Warsaw for Antwerp, and finally arriving at a cold-water flat on the Lower East Side. My parents were not only exhausted by the journey, they were stupefied. In the end, the only question that truly preoccupied them was one that, in my bohemian youth, I dismissed as greenhorn sentimentality, and now, in old age, is the only question I, myself, ask: Where is home, and how do I get there?

Like the children of most fresh-off-the-boat Jews, I attended the only school my parents could comprehend, let alone afford: a landsman's quasi Hebrew school conducted in a cellar and lorded over by a succession of rod-wielding, self-appointed rabbis. My education consisted primarily of chanting Hebrew songs without having the least notion of, or reverence for, what I was singing.

The islanders believe that language originates in song, and that the human throat is a musical instrument, a flute of flesh and blood, and that the breath reverberating through the flute is the soul, and that the music emerging from the flute is the spirit.

Aside from a few deeply ingrained Hebrew songs, everything else has been lost to me from those years. I have, after all, been gone so long. The only keepsake I have is an ancient newspaper clipping, a gift from the archivist at the Yiddish Library who'd read about me in Life: it's a 1916 "Bintel Brief," the advice column of the Jewish Daily Forward, in which a letter of my father's was printed.

Dear Esteemed Editor,

I hope you will advise me in my present difficulty. I come from a small town in Russia, where, until I was twenty, I studied the Torah, but when I came to America, I quickly changed. I was influenced by progressive newspapers, and became a freethinker and a socialist. But the nature of my feelings is remarkable.

Listen to me: every year when the month of Elul rolls around, when the time of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur approaches, a melancholy begins to eat at my heart, like rust eats iron. When I go past a synagogue during those days and hear the cantor singing, my yearning becomes so great I cannot endure it. I see before me the small town, the fields, the little pond, the yeshiva. I recall my childhood friends and our sweet childlike faith. My heart constricts, and I run like a madman till the tears stream from my eyes and I become calmer.

Lately, I have returned to synagogue, despite the scorn of my freethinker daughter. I go not to pray to God, but to hear and refresh my aching soul with the cantor's melodies. I forget my unhappy weekday life, the dirty shop, my boss, the bloodsucker. All of America with its hurry-up life is forgotten.

What is your opinion of this? Are there others like me whose natures are such that memories of their childhood songs are sometimes stronger than their convictions? I await your answer.

Respectfully yours,

Benjamin Rabinowitz

I offer you my father's letter not to woo you with nostalgia, but because if there were an untouched square of skin left on my body, I would engrave it on my flesh.

Jewish law forbids tattooing: Thou shall not make in thy flesh a scratch over the soul. But what if the Ta'un'uuans are right, and the soul is breath? Then aren't the scratches left on my soul by my needles really just the moments when my breath caught, my voice cracked, unable to find song?

By sixteen, I had become, in my father's words, a freethinker, and by my own definition, a bohemian and an anarchist, a girl for whom religion and its trappings were irrelevant. To bring the point home to my parents, I would invariably light my after-dinner cigarette in the flame of the Sabbath candles.

I was a seamstress by day, a waist maker, the eighteenth girl in a row of twenty at the windowless end of the warehouse. Shopgirls worked their way toward the light by seniority. By week's end, my fingers would be so scratched and marred by the needles that one can't attribute all the abrasions on my soul to the tattoos. But on Saturday nights, I'd don my shopgirl's version of bohemian--a felt hat with purple plumage, a Gypsy skirt, and two immoral shanks of red stocking. My destination was Greenwich Village. The cultural gulf between the Lower East Side and Washington Square was probably greater than the one my parents had encountered when they left the steppes of Russia for Avenue D. At best, I'd covet a bench at the base of Stanford White's arch, sharing cigarettes with versions of myself, gaudily feathered shopgirls in whose discontented stares one could just make out little compressed diamonds of ambition. At worst, I'd wander the square by myself, catching glimpses of what anyone could plainly see were the real bohemians--paint-splattered artists, mustachioed socialists, regal-necked poetesses arguing away while ash spilled from the gold tips of their cigarette holders. The schism between them and me in my red stockings and cheap plumage, seemed as impossible to surmount as that between the gods and man.

For shopgirls like me, East Side Jews who spoke with guttural accents, the only lifeline out of workaday hell was the Educational Alliance, the center of Yiddish intelligentsia, a curious mix of night school, public forum, gymnasium, and revolutionary cells. The center had been a gift from a few philanthropic German Jews to their hardscrabble East European brethren. Sunday afternoons, young Zionists who could barely remember to water their mothers' rubber plants took to the stage to call for the transformation of an arid desert into a Jewish Eden. Ex-yeshiva shopboys, for whom the threading of a sewing machine was a daunting task, called for a futuristic mechanized utopia on earth.

My union, the Ladies' Waist Makers' Union, bought blocks of tickets for the Alliance's Sunday night lecture series: "Jews and the Graven Image"; "Is Marxism Scientific?"; "Revolution: If Not Now, When? If Not Us, Who?"; "The Jewish Themes of Ibsen."

One evening, an artist, an American Jew who had been educated in Zurich and Berlin, who had lived in Paris and Moscow, who spoke with intimacy about Picasso, Freud, and Trotsky as I might gossip about the girl at the next sewing machine, addressed us waist makers, and the boys from the Buttonhole Makers' and Collar Makers' unions, on the twentieth-century collision between art, the subconscious, and revolution.

A giant of a man, he had to stoop to reach the lectern. He had shoulder-length blond hair that he tossed to make his points. In a buckskin jacket and red silk vest, he dressed, to my mind at least, like a cross between Buffalo Bill and what I assumed was a Parisian painter. He told us that the art of the future would be made by the proletariat, workers just like us, then described the squalor of our shop life in enough glorious abstraction that it actually seemed possible. He explained how our subconscious, the antechamber of our unconscious, held within its misty foyer all the symbols we'd ever need. He urged us to have faith that art, with its noble and redemptive powers, would use those symbols to provide our beleaguered souls with the metaphors by which we could transform our misery into meaning. And when the time was right, he insisted that art would even spur us into revolution.

Did I believe him? A ragtag army of seamstresses and ex-yeshiva buchers advancing on Park Avenue brandishing needles and Symbolist paintings? What was the alternative? Fifty more years at a sewing machine? A tiny air shaft apartment facing a teenier one, my only view my neighbor's life? Whimpers, moans, hacks, grunts, fits of coughing, fits of prayer resounding through the thin walls? On the Lower East Side, the unconscious was not the symbol-laden fog of Freud and art. The unconscious was sleep or, if it lasted long enough, death.

Whatever doubts I had about his lecture I quickly quashed, as one might instinctively step on a dark shape in the periphery of one's vision.

When he climbed off the podium, I and a dozen other shopgirls surrounded him. He glanced down at us with bemused curiosity and teased us that his lecture would be followed by an impromptu quiz. He reached into the fringed pocket of his jacket and plucked out a gold cigarette case. Tapping his thumbnail on the tooled casing, he asked if any of us ladies would like to try a French cigarette? I was the only one to accept. I leaned into his lit match as defiantly as I leaned into the Sabbath flame. The rumor was that when he'd lectured at the Alliance the year before, he'd bedded only the prettiest of his admirers, comely girls with dreams as fragile as soap bubbles, girls who giggled at his rarefied allusions as others might nervously guffaw at a funeral. I wasn't particularly pretty, and I never giggled.

It would be easy to pretend that after thirty years among the islanders with their forthright sexuality, their worship of the body, I've lost all tolerance for the curtsies and bows, the feints and feigns of Western courtship. But even as a young woman, I detested coyness. Suffice it to say, when the other girls dispersed, it was I who followed him home, and I who seduced Philip.

His portrait graces my left breast. It is the first tattoo I engraved on myself. The portrait, however, in no way resembles the face I kissed that night; an unlined, untested face of cavalier certitude that the future would be as easy to read as a palm. The face on my left breast is desecrated, pillaged of all illusions, and though it breaks my heart to admit it, it is also the weakest part of my design--the point on my flesh where my emotions exceeded my skill--and no amount of virtuosity can disguise that weakness. The face on my left breast is a living death mask, as far removed from the young Philip as I am from the girl I was.

He lived in a refurbished livery stable on Washington Mews, refurbished with Carrara marble, Art Nouveau windows, Persian carpets, a Brancusi bronze, a gilt-framed Gauguin, and a collection of South Pacific masks. I was so ill educated, I didn't even know enough to be impressed. I thought the masks were examples of modern art. I walked up to the Gauguin and asked if Philip had painted it. When he laughed and shook his head, his hair whipped against his throat. I was too embarrassed to ask anything else. Just to end my ungainly silence, I unbuttoned my blouse and put my own collateral on display. I could see how amused he was by my brazenness. I was hardly amused; I was astounded by my daring. I let him finish the job, undoing the buttons, eyelets, hooks, and laces that confined me. I was and I wasn't a virgin. I'd had rudimentary sex the month before with a buttonhole maker on the Alliance's tar roof. Afterward, the boy and I declared ourselves freethinkers and never spoke to each other again.

Philip made love to me on his Hindoo blue settee. A practiced and precise lover, he believed his sojourns into the subconscious, his experiments with what he called "Surrealism," had led him to new levels of sensuality. I was hardly prepared to be the judge of that. I was still learning how to kiss.

I stayed with Philip for three nights and two days. He introduced me to the practice of automatic drawing after sex. With him, I tasted my first glass of champagne, my first bite of trayf. But what impressed me most, what trumps all my other memories despite half a century, is that Philip owned a telephone, an elegant black instrument on a fluted pedestal. I'd never seen one in a private house before. Whenever it rang, Philip grew exasperated, but I felt we were at the center of the world.

When I finally returned home, my frantic mother demanded to know where I'd been, and when I shamelessly told her, she called me a nafka, a whore, and wouldn't speak to me. The logistics of our not talking in a two-room tenement were complex. We had to steal past each other without so much as our breaths mingling. I had to bear witness to her mumbled quips without so much as a snipe back. Only my father, who had begun residing more and more in the bucolic fantasy of his Russian childhood, would speak to me. And only when my mother wasn't home.

"Sara, do you see that wall?" He had taken to believing that not only our tenement, but the sweatshop, his boss, all of America with its hurry-up life, was only a figment of his dreams. "That wall isn't a wall. That wall is the inside of my coffin." He took out his tefillin and prayer shawl, then kissed my cheek. "But you're not to worry, mein kint, I'll soon wake up."

I packed what little I had and left him davening toward the east, an air shaft strung with laundry, singing what must be the most heartrending of prayers, "Thank you God for returning to me my soul, which was in Your keeping."

I found lodging with six Litvak sisters from my union in a cellar apartment on Ludlow Street. My bed was the board that covered the kitchen tub. All night long, directly under my ear, the faucet leaked in fits and dribbles. My dreams sputtered and raced in time to that watery metronome, save for the nights that I slept beside Philip.

I wasn't his only lover: he made that unequivocally clear. He also made the conditions of my spending the night in his bed as complicated as a wedding contract. I couldn't stay for more than three consecutive nights. I couldn't keep any of my possessions in his closets or drawers. I was never to answer the telephone, though when it trilled, I pined to.

Recenzii

“An eerily beautiful novel of artistic ambition and a woman’s struggle to be at home in her skin.”

–O, The Oprah Magazine

“The Tattoo Artist was a fever dream from which I did not wish to wake.” –Alice Sebold, author of The Lovely Bones

–O, The Oprah Magazine

“The Tattoo Artist was a fever dream from which I did not wish to wake.” –Alice Sebold, author of The Lovely Bones