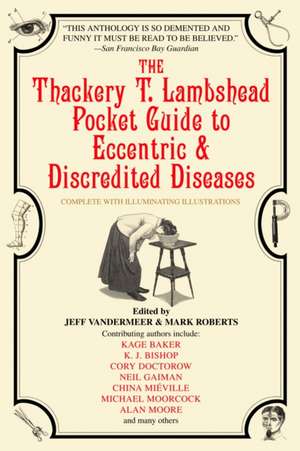

The Thackery T. Lambshead Pocket Guide to Eccentric & Discredited Diseases

Autor Mark Roberts, Jeff VanderMeeren Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mar 2005

You hold in your hands the most complete and official guide to imaginary ailments ever assembled—each disease carefully documented by the most stellar collection of speculative fiction writers ever to play doctor. Detailed within for your reading and diagnostic pleasure are the frightening, ridiculous, and downright absurdly hilarious symptoms, histories, and possible cures to all the ills human flesh isn’t heir to, including Ballistic Organ Disease, Delusions of Universal Grandeur, and Reverse Pinocchio Syndrome.

Lavishly illustrated with cunning examples of everything that can’t go wrong with you, the Lambshead Guide provides a healthy dose of good humor and relief for hypochondriacs, pessimists, and lovers of imaginative fiction everywhere. Even if you don’t have Pentzler’s Lubriciousness or Tian Shan-Gobi Assimilation, the cure for whatever seriousness may ail you is in this remarkable collection.

Preț: 130.08 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 195

Preț estimativ în valută:

24.90€ • 25.92$ • 21.04£

24.90€ • 25.92$ • 21.04£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 17 februarie-03 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780553383393

ISBN-10: 0553383396

Pagini: 320

Dimensiuni: 154 x 230 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.41 kg

Editura: Bantam

ISBN-10: 0553383396

Pagini: 320

Dimensiuni: 154 x 230 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.41 kg

Editura: Bantam

Notă biografică

Editor Jeff VanderMeer is the author of two short story collections, City of Saints and Madmen and A Secret Life, and one novel, Veniss Underground. He has also edited anthologies Leviathan 1, 2, and 3, the last a World Fantasy Award winner and Philip K. Dick award finalist.

Mark Roberts runs Chimeric, a graphic design firm, and has been involved in several publishing ventures through the publisher arm of Chimeric. An accomplished illustrator and writer, his work has appeared in Interzone, The Third Alternative, The New York Review of SF, and many others. Along with his co-editor, Jeff VanderMeer, he has been a finalist for the Hugo Award and the World Fantasy Award for his work on the fake disease guide. He lives in London, England.

Mark Roberts runs Chimeric, a graphic design firm, and has been involved in several publishing ventures through the publisher arm of Chimeric. An accomplished illustrator and writer, his work has appeared in Interzone, The Third Alternative, The New York Review of SF, and many others. Along with his co-editor, Jeff VanderMeer, he has been a finalist for the Hugo Award and the World Fantasy Award for his work on the fake disease guide. He lives in London, England.

Extras

BALLISTIC ORGAN SYNDROME

Ballistitis

Country of Origin

Java (Indonesia)

First Known Case

Ballistic Organ Syndrome, although rare, has been known since prehistoric times. In Australasia and Micronesia, cave paintings have been found depicting humans and animals with internal organs erupting from their bodies. (1)

Symptoms

Ballistic Organ Syndrome manifests as a sudden, explosive discharge of one or more bodily organs at high velocity; this exit may be accompanied by some pain. There are two known variants: subsonic Ballistitis, in which the velocity of ejection does not exceed that of sound, and distinguished by an explosive discharge from throat or anus accompanied by a release of wet, atomized bodily contents; and supersonic Ballistitis, in which the organ exits the body by the path of least resistance, breaking free directly through muscle, tendon, bone, and skin tissues.

Supersonic Ballistitis is the more dangerous manifestation, as the ejecta exceed the speed of sound and therefore strike without warning. Surprisingly, however, the high energy of supersonic Ballistitis discharge cauterizes the surface of the organ and sterilizes the ejected bodily contents, so that the overall risk of infection is less than that of subsonic Ballistitis.

In rare cases, the Ballistitis virus infects the patient's entire body. Eventually, some event causes one or more cells to rupture, after which the patient's body is disrupted in an explosive ejection of all bodily organs. This manifestation of the syndrome frequently occasions the death of the patient; at best, the loss of all bodily organs will cause considerable inconvenience and distress (as set out in Doctor Buckhead Mudthumper's Encyclopedia of Forgotten Oriental Diseases).

History

During the 1709 siege of Batavia (today Jakarta), the Sultan of Solo used Ballistitis-infected slaves as catapult ammunition, in hopes of injuring (and infecting) enough of the Dutch defenders to render their fortications untenable. Fortunately for the Dutch the governor of Batavia, Pieter van Tilberg, was familiar with Ballistitis from his service as a surgeon's assistant in Celebes (today Sulawesi). Van Tilberg ordered that infected citizens be expelled from the city; those infected individuals wreaked havoc among the besieging Javanese. Pieter van Tilberg later wrote an epic poem, "The Liver's Red Glare," in commemoration of the Dutch victory.

It is obvious from this account, however, that Ballistitis must have been endemic throughout the Indonesian Archipelago for years, if not centuries, prior to this event.

Randolph Johnson spent several months in the Indonesian Archipelago, searching for Ballistitis sufferers in hope of collecting case studies for his posthumously-published Confessions of a Disease Fiend, an autobiographical account of the tragic sexual obsession that culminated in his death. During sexual congress with a catamite in Mataram (Lombok, Indonesia), Johnson lost an arm to a supersonic Ballistitis discharge. Johnson was evacuated to Singapore aboard the Royal Navy frigate Indomitable, but died en route.

Cures

Ballistitis is known to be caused by a retrovirus that reprograms body cells to concentrate water at extremely high pressures. This buildup may continue for days or weeks, until one or more cells is ruptured and the pressure is released in a steam explosion. This initiates a chain reaction of other infected cells, causing one or more organs to be ejected with great force. The violence of supersonic Ballistitis is more likely to trigger adjacent cell detonation, and so a supersonic ejection is unlikely to be followed by subsequent ejections; subsonic Ballistitis eruptions, however, may continue until no organs remain in the body cavity. As reported in The Journals of Sarah Goodman, Disease Psychologist, both forms of the disorder occasion some distress on the part of the patient.

The Ballistitis retrovirus may be transmitted through direct contact with organic ejecta or through inhalation of atomized bodily contents. Medical personnel dealing with infected patients are strongly recommended to seek the advice of a military fortifications engineer to assist in deploying sandbagging and overhead protection, as ejected organs can travel a considerable distance and explode with some force on impact. When handling a patient at close quarters, respirator masks and ballistic body armor are strongly recommended as prophylaxis. Under no circumstances should a patient be immersed in water or any similarly incompressible fluid, placed in close proximity to load-bearing members of any structure, or surrounded by objects that might become lethal shrapnel in the event of an explosion.

In cases where one or a few organs have been ejected, organ transplantation is a useful means of restoring organic function; the surgeon should, however, ensure that all infected tissue has been excised. Unwary surgeons have worked for hours to save a patient's life, only to have the recently-implanted organ rejected in spectacular (and hazardous) fashion.

Submitted by

Dr. Michael Barry, Institute of Psychiatric Venereology, Hughes, Australian Capital Territory

Endnote

(1) "Explosive Ejection of Bodily Contents In Prehistoric Cave Art: A Medical Mystery Solved?" by James H. Twickenham, in Tropical Diseases Quarterly vol. 12.

Cross References

Buboparazygosia; Diseasemaker's Croup; Motile Snarcoma; Pentzler's Lubriciousness

BLOODFLOWER'S MELANCHOLIA

Country of Origin

England

First Known Case

The first and, in the opinion of some authorities, the only true case of Bloodflower's Melancholia appeared in Worcestershire, England, in the summer of 1813. The local doctor professed himself baffled by the symptoms of Squire Bloodflower's eldest son, Peter, then a youth of 18. "In all my many years as a physician," he wrote in his diary, only recently discovered, "I have never encountered such a puzzling and recalcitrant malady, whose origin must surely lie in the mysteries of the human soul."

Symptoms

"Since entering manhood the young Peter had manifested a distinguished gloom, which, on his achieving his majority, blossomed into a consummate mania. He shunned all active pursuits and dressed entirely in black. The sight of something as simple as sunshine or as innocent as a flower reduced him to tears of grief. He rejected normal sustenance, and exhibited a compulsion to drink ink and to eat paper. When these staples were put out of reach he began to consume his books; and on these being removed he retreated into a primitive and immobile state, akin to that of the embryo in the womb, from which he emerged only by God's grace and in his own good time." (From the diaries of Dr. Amos Smith, Worcester County Library)

History

Although Peter Bloodflower's is the first recorded case, there is reason to suspect a previous history of instability in the family (notably that of his aunt, Laetitia Bloodflower, who ended her days in a convent in Provence), which for reasons of social nicety had been carefully concealed. On recovering from his first attack, in the autumn of 1816, Peter went to London where he became part of the Romantic circle, mixing freely with such luminaries as Keats and Shelley, and, it is thought, making a considerable impression on their receptive minds. Keats' "Ode on Melancholy" is thought to have been addressed to him. It is likely, however, that Bloodflower's real interest lay with Keats' former roommate and fellow medical student, Henry Stephens, who may have developed his famous blue-black ink for the express purpose of satiating Bloodflower's secret thirst.

However, the true notability--and controversy--of Bloodflower's Melancholia lies in its hereditary character. According to the journals of Sarah Goodman, the distinguished disease psychologist, "no other disorder of the appetites and the emotions has manifested itself with such repeated exactness in successive generations of the same family." Nor, she might have added, amongst so wide a scattering of its members. Charcot's treatment of Justine Fleur-de-Sang at the Salpetriere in 1865, and Freud's encounter with Hans Blutblum in Vienna in 1926, bear witness to the familial tenacity of the condition. Not to mention the direct descendants of Peter Bloodflower, resident in Worcestershire until this very day. Each one has exhibited the same ink-drinking and paper-eating tendencies, combined with extreme Weltschmerz, "as if," in the words of Dr. Smith, "the weight of nature were too great for his fragile spirit to endure."

There are, however, those who dispute the existence of Bloodflower's Melancholia in its hereditary form. Randolph Johnson is unequivocal on the subject. "There is no such thing as Bloodflower's Melancholia," he writes in Confessions of a Disease Fiend. "All cases subsequent to the original are in dispute, and even where records are complete, there is no conclusive proof of heredity. If anything we have here a case of inherited suggestibility. In my view, these cannot be regarded as cases of Bloodflower's Melancholia, but more properly as Bloodflower's Melancholia by Proxy."

If Johnson's conclusions are correct, we must regard Peter Bloodflower as the sole true sufferer from this distressing condition, a lonely status that possesses its own melancholy aptness.

Outcome and Cures

This type of melancholia does not generally prove fatal. Peter Bloodflower, despite recurrent episodes, lived a long and fecund life. Only two cases of possible suicide in the Bloodflower family have occurred: that of Arthur Bloodflower, who died in 1892 of ink poisoning (his favored brand contained high quantities of vitriol) and that of Horatio Bloodflower, who according to legend drowned in his own tears.

There is probably no cure for Bloodflower's Melancholia, or, for that matter, for Bloodflower's Melancholia by Proxy. Peter Bloodflower was, of course, subjected to the sole treatment available in his time: "I bled him six ounces," writes Smith, "and found his blood to be as black as ink." Freud found it non-amenable to psychoanalysis. "A grief whose sources lie in the very wellsprings of existence," he wrote, "may never, I fear, be truly capable of cure." Modern advances in genetics may yet hold the key to its eradication, or prove, at least, its claim to join the ranks of genuine hereditary diseases.

Submitted by

Dr. Tamar Yellin

Cross References

Diseasemaker's Croup; Menard's Disease; Monochromitis; Poetic Lassitude; Rashid's Syndrome

BONE LEPROSY

Turkish Bone Leprosy,

or Saint Calamaro's Leprosy

Introduction

Hansen's disease, commonly known as leprosy, is a long-acting microbial infection. Its lengthy dormancy period has created confusion regarding its modes of transmission. However, the active organism, Mycobacterium leprae, has been isolated, and many modern cases can be reversed by antibiotics. In medieval Turkey, things were very different.

History

In the Christian year 1510, Bayezid the Second ruled the Ottoman Empire. On the shores of the Black Sea, at the mouth of the Sakarya River, there was a colony for lepers called Saint Augustine's Retreat. The lepers grew barley and made goat cheese. Their needs for commerce with the outside world were met by an adjacent community, the Franciscan monks of The Order of Saint Augustine, who maintained the leprosarium.

Throughout the existence of the colony, it attracted a steady stream of pilgrim lepers, who walked there from as far away as Greece and Persia. In roughly 1520 a new form of Hansen's disease appeared among the pilgrims. The Franciscans called it bone leprosy.

Symptoms

The basic distinction here is easy to grasp. The hallmark symptom of normal leprosy is that necrotic flesh falls from the bones of the extremities. In bone leprosy, the bones of the extremities fall from the flesh.

First the blackened bones of the fingers and toes would poke themselves bloodlessly through the skin and detach. Next the metacarpals and metatarsals disassembled themselves and emigrated. At this stage the victim could still walk on his ankles with the help of crutches. But then the long bones of the four limbs would emerge into the light of day and discard themselves.

The chronicle of Father Ambrosius, the last abbot of The Order of Saint Augustine, reports that one bone leper also lost his pelvis, scapulars, and clavicles, and got along with only a skull, a spine, and some ribs. This man called himself Vecchio Calamaro, "the old squid." He may have been born in Italy.

Further History

By 1530 many bone lepers could be seen among the hovels of the colony, squirming across the earth like giant sea stars. But the "Normal Lepers" distrusted "the Boneless Ones" and finally attacked them with clubs and drove them from the colony.

The Boneless Ones slithered away and formed their own settlement on a barren plateau that overlooked the monastery, the leprosarium, and the river. They drew water from a mountain stream and grew vegetables and spices. At the instruction of Father Ambrosius, the monks brought them barley and milk on the sly. An uneasy truce ensued between the two leper colonies.

In 1534, during the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent, Old Calamaro experienced a religious epiphany. He communicated this vision to his fellow pariahs with such force that they reorganized themselves as a lay brotherhood. They committed their lives to penance, holy poverty, and the contemplation of Christ's mercies. Calamaro went to live in a pit lined with stones, like a shallow well shaft or a lidless oubliette. He dug this pit himself, using only his teeth and a wooden spoon.

As the years progressed, more and more of the Boneless took vows and became visionary hermits, living in the sunken circular cells that dotted the plateau. They seldom spoke, but their echoing chants at dawn and dusk could be heard by Father Ambrosius at Saint Augustine's. Certainly the Boneless Ones had surpassed the Franciscans in their pursuit of austerity. Ambrosius felt no temptation to envy them their accomplishment. (1)

The only existing record of The Order of Saint Augustine and the two leprosariums concludes with the death of Ambrosius. The monastery walls have been toppled by earthquakes.

But Old Calamaro is remembered to this day as Saint Calamaro of the Russian Orthodox Church. A few of the "prayer pits" of his brotherhood have been preserved for visitation near the modern town of Karasu.

Hagiography

A hagiography is not, of course, medical data. I present this excerpt from Saint Calamaro's notwithstanding, freely translated from an anonymous Latin parchment. Please consider it as a curious footnote to the social history of leprosy.

The miracles of Saint Calamaro were three in number, and three in number were his trials, the first being a trial by hunger.

It came to pass that the hearts of the Normal Lepers were enflamed against their bone-bereft neighbors. And the Normals didst resolve to accost those gentle Franciscans who went forth each day to pass among the Boneless. For the Normals deemed it folly to risk contagion from such an unnatural affliction as bonelessness. And they shouted at the monks, saying, "Shun the unclean! Your charity could get us all deboned!"

And they didst smite those humble monks, and lo they broke many heads. For they grew cruel when they got a little wine into them. And Father Ambrosius didst resign himself to abandon the Boneless.

And further the Normals didst rip up the Boneless Ones' gardens and didst foul the pure water of their stream.

For 40 days and nights, the Boneless drank only the morning dew that condensed on the walls of their cells, and ate only the tiny creeping things that they found within their clothes. And yet they thirsted not, nor didst they hunger. For the grace of Saint Calamaro's first miracle was upon them.

The second trial of the saint was a trial by drowning. For indeed the Normals didst arise again against him and didst drag him from his pit. And none of his followers resisted the Normals, but rather they prayed more loudly to drown out his cries for help. For the Boneless were sore afraid.

And in consequence the Normals didst bind the saint within a sack, and drag the sack across sharp rocks to a boat, and row this boat a great distance across the Black Sea. And there they didst abuse the saint and kick him in his private parts and throw him overboard and leave him to drown. And the Normals were well satisfied, even though an ear, a nose, and several of their fingers had been lost in the scuffle.

In his aquatic extremity, the saint lost not his faith in his Savior, but didst call out loudly to the Lord, with many Italianate profanities, in fear and in trembling and with evil-tasting water in his mouth. And his prayers were answered, for like unto the rainbow-dappled jellyfish, he didst float upon the sea, nor did he sink.

The Normals didst row to shore and make straight for their dining hall, for drowning cripples always made them thirsty. And lo the second miracle! At their dining hall, they found their cook in great dismay. For Saint Calamaro had appeared in her largest stew pot and was eating all the stew.

Then the saint's final trial was upon him, which was a trial by boiling in oil. For the outraged Normals didst pour much olive oil into that soup pot and didst clamp down the lid with great force and three carpenter's vices. And they didst convey the soup pot to an open space between their hovels, where they soon amassed the makings for a bonfire. Mightily that conflagration raged about the soup pot. And the Normals danced and shouted, saying, "This is how we cook a squid in Turkey!"

But when the fires died, and the soup pot was opened, there was nothing inside. And just as the Normals saw this ominous emptiness, a chuckling was heard.

And lo the third miracle! It was Old Calamaro. He was inside the dining hall again, feasting on almonds and custards and wine. And seeing this, the Normals didst flee in fright from the doings of this leprous magus.

And though he was never seen again, peace reigned forever after between the Normals and the Boneless. For it was said among them that Old Calamaro had melted into the shingle at the shore, like unto an icicle in the sunshine. And they said that he dwelt now in the earth beneath their sandals, and that he watched all the lepers of the world, lest they ever again mistreat the wretched.

But in truth the Old Squid ascended to the Land of Light and sits now among the choirs of the angels in the throne room of the Lord. Perhaps he even sits on a velvet stool beside the Savior's giant golden throne.

Or perhaps--who can say?--he reclines more comfortably on the white marble floor beneath the throne, peering out from his special place between the four golden legs. Perhaps he reclines on a tasteful Persian rug, eating stewed prunes with a silver spoon. Perhaps he smiles down toothlessly on all the prostrate supplicants arrayed before God's throne. Perhaps he shakes his head and chuckles, as they beg for mercy.

Submitted by

Stepan Chapman, Doctor of Pandemics

Endnote

(1) Father Ambrosius wrote the following scrap of Latin verse into a margin of his chronicle.

Shunned by their unclean brethren,

Who are shunned by the monks of my order,

Who in turn are barely tolerated

By the Moslem that surround us.

Who is the lowliest of the low?

Who is most outcast?

Cross References

Chronic Zygotic Dermis Disorder; Diseasemaker's Croup; Extreme Exostosis; Razornail Bone Rot

Ballistitis

Country of Origin

Java (Indonesia)

First Known Case

Ballistic Organ Syndrome, although rare, has been known since prehistoric times. In Australasia and Micronesia, cave paintings have been found depicting humans and animals with internal organs erupting from their bodies. (1)

Symptoms

Ballistic Organ Syndrome manifests as a sudden, explosive discharge of one or more bodily organs at high velocity; this exit may be accompanied by some pain. There are two known variants: subsonic Ballistitis, in which the velocity of ejection does not exceed that of sound, and distinguished by an explosive discharge from throat or anus accompanied by a release of wet, atomized bodily contents; and supersonic Ballistitis, in which the organ exits the body by the path of least resistance, breaking free directly through muscle, tendon, bone, and skin tissues.

Supersonic Ballistitis is the more dangerous manifestation, as the ejecta exceed the speed of sound and therefore strike without warning. Surprisingly, however, the high energy of supersonic Ballistitis discharge cauterizes the surface of the organ and sterilizes the ejected bodily contents, so that the overall risk of infection is less than that of subsonic Ballistitis.

In rare cases, the Ballistitis virus infects the patient's entire body. Eventually, some event causes one or more cells to rupture, after which the patient's body is disrupted in an explosive ejection of all bodily organs. This manifestation of the syndrome frequently occasions the death of the patient; at best, the loss of all bodily organs will cause considerable inconvenience and distress (as set out in Doctor Buckhead Mudthumper's Encyclopedia of Forgotten Oriental Diseases).

History

During the 1709 siege of Batavia (today Jakarta), the Sultan of Solo used Ballistitis-infected slaves as catapult ammunition, in hopes of injuring (and infecting) enough of the Dutch defenders to render their fortications untenable. Fortunately for the Dutch the governor of Batavia, Pieter van Tilberg, was familiar with Ballistitis from his service as a surgeon's assistant in Celebes (today Sulawesi). Van Tilberg ordered that infected citizens be expelled from the city; those infected individuals wreaked havoc among the besieging Javanese. Pieter van Tilberg later wrote an epic poem, "The Liver's Red Glare," in commemoration of the Dutch victory.

It is obvious from this account, however, that Ballistitis must have been endemic throughout the Indonesian Archipelago for years, if not centuries, prior to this event.

Randolph Johnson spent several months in the Indonesian Archipelago, searching for Ballistitis sufferers in hope of collecting case studies for his posthumously-published Confessions of a Disease Fiend, an autobiographical account of the tragic sexual obsession that culminated in his death. During sexual congress with a catamite in Mataram (Lombok, Indonesia), Johnson lost an arm to a supersonic Ballistitis discharge. Johnson was evacuated to Singapore aboard the Royal Navy frigate Indomitable, but died en route.

Cures

Ballistitis is known to be caused by a retrovirus that reprograms body cells to concentrate water at extremely high pressures. This buildup may continue for days or weeks, until one or more cells is ruptured and the pressure is released in a steam explosion. This initiates a chain reaction of other infected cells, causing one or more organs to be ejected with great force. The violence of supersonic Ballistitis is more likely to trigger adjacent cell detonation, and so a supersonic ejection is unlikely to be followed by subsequent ejections; subsonic Ballistitis eruptions, however, may continue until no organs remain in the body cavity. As reported in The Journals of Sarah Goodman, Disease Psychologist, both forms of the disorder occasion some distress on the part of the patient.

The Ballistitis retrovirus may be transmitted through direct contact with organic ejecta or through inhalation of atomized bodily contents. Medical personnel dealing with infected patients are strongly recommended to seek the advice of a military fortifications engineer to assist in deploying sandbagging and overhead protection, as ejected organs can travel a considerable distance and explode with some force on impact. When handling a patient at close quarters, respirator masks and ballistic body armor are strongly recommended as prophylaxis. Under no circumstances should a patient be immersed in water or any similarly incompressible fluid, placed in close proximity to load-bearing members of any structure, or surrounded by objects that might become lethal shrapnel in the event of an explosion.

In cases where one or a few organs have been ejected, organ transplantation is a useful means of restoring organic function; the surgeon should, however, ensure that all infected tissue has been excised. Unwary surgeons have worked for hours to save a patient's life, only to have the recently-implanted organ rejected in spectacular (and hazardous) fashion.

Submitted by

Dr. Michael Barry, Institute of Psychiatric Venereology, Hughes, Australian Capital Territory

Endnote

(1) "Explosive Ejection of Bodily Contents In Prehistoric Cave Art: A Medical Mystery Solved?" by James H. Twickenham, in Tropical Diseases Quarterly vol. 12.

Cross References

Buboparazygosia; Diseasemaker's Croup; Motile Snarcoma; Pentzler's Lubriciousness

BLOODFLOWER'S MELANCHOLIA

Country of Origin

England

First Known Case

The first and, in the opinion of some authorities, the only true case of Bloodflower's Melancholia appeared in Worcestershire, England, in the summer of 1813. The local doctor professed himself baffled by the symptoms of Squire Bloodflower's eldest son, Peter, then a youth of 18. "In all my many years as a physician," he wrote in his diary, only recently discovered, "I have never encountered such a puzzling and recalcitrant malady, whose origin must surely lie in the mysteries of the human soul."

Symptoms

"Since entering manhood the young Peter had manifested a distinguished gloom, which, on his achieving his majority, blossomed into a consummate mania. He shunned all active pursuits and dressed entirely in black. The sight of something as simple as sunshine or as innocent as a flower reduced him to tears of grief. He rejected normal sustenance, and exhibited a compulsion to drink ink and to eat paper. When these staples were put out of reach he began to consume his books; and on these being removed he retreated into a primitive and immobile state, akin to that of the embryo in the womb, from which he emerged only by God's grace and in his own good time." (From the diaries of Dr. Amos Smith, Worcester County Library)

History

Although Peter Bloodflower's is the first recorded case, there is reason to suspect a previous history of instability in the family (notably that of his aunt, Laetitia Bloodflower, who ended her days in a convent in Provence), which for reasons of social nicety had been carefully concealed. On recovering from his first attack, in the autumn of 1816, Peter went to London where he became part of the Romantic circle, mixing freely with such luminaries as Keats and Shelley, and, it is thought, making a considerable impression on their receptive minds. Keats' "Ode on Melancholy" is thought to have been addressed to him. It is likely, however, that Bloodflower's real interest lay with Keats' former roommate and fellow medical student, Henry Stephens, who may have developed his famous blue-black ink for the express purpose of satiating Bloodflower's secret thirst.

However, the true notability--and controversy--of Bloodflower's Melancholia lies in its hereditary character. According to the journals of Sarah Goodman, the distinguished disease psychologist, "no other disorder of the appetites and the emotions has manifested itself with such repeated exactness in successive generations of the same family." Nor, she might have added, amongst so wide a scattering of its members. Charcot's treatment of Justine Fleur-de-Sang at the Salpetriere in 1865, and Freud's encounter with Hans Blutblum in Vienna in 1926, bear witness to the familial tenacity of the condition. Not to mention the direct descendants of Peter Bloodflower, resident in Worcestershire until this very day. Each one has exhibited the same ink-drinking and paper-eating tendencies, combined with extreme Weltschmerz, "as if," in the words of Dr. Smith, "the weight of nature were too great for his fragile spirit to endure."

There are, however, those who dispute the existence of Bloodflower's Melancholia in its hereditary form. Randolph Johnson is unequivocal on the subject. "There is no such thing as Bloodflower's Melancholia," he writes in Confessions of a Disease Fiend. "All cases subsequent to the original are in dispute, and even where records are complete, there is no conclusive proof of heredity. If anything we have here a case of inherited suggestibility. In my view, these cannot be regarded as cases of Bloodflower's Melancholia, but more properly as Bloodflower's Melancholia by Proxy."

If Johnson's conclusions are correct, we must regard Peter Bloodflower as the sole true sufferer from this distressing condition, a lonely status that possesses its own melancholy aptness.

Outcome and Cures

This type of melancholia does not generally prove fatal. Peter Bloodflower, despite recurrent episodes, lived a long and fecund life. Only two cases of possible suicide in the Bloodflower family have occurred: that of Arthur Bloodflower, who died in 1892 of ink poisoning (his favored brand contained high quantities of vitriol) and that of Horatio Bloodflower, who according to legend drowned in his own tears.

There is probably no cure for Bloodflower's Melancholia, or, for that matter, for Bloodflower's Melancholia by Proxy. Peter Bloodflower was, of course, subjected to the sole treatment available in his time: "I bled him six ounces," writes Smith, "and found his blood to be as black as ink." Freud found it non-amenable to psychoanalysis. "A grief whose sources lie in the very wellsprings of existence," he wrote, "may never, I fear, be truly capable of cure." Modern advances in genetics may yet hold the key to its eradication, or prove, at least, its claim to join the ranks of genuine hereditary diseases.

Submitted by

Dr. Tamar Yellin

Cross References

Diseasemaker's Croup; Menard's Disease; Monochromitis; Poetic Lassitude; Rashid's Syndrome

BONE LEPROSY

Turkish Bone Leprosy,

or Saint Calamaro's Leprosy

Introduction

Hansen's disease, commonly known as leprosy, is a long-acting microbial infection. Its lengthy dormancy period has created confusion regarding its modes of transmission. However, the active organism, Mycobacterium leprae, has been isolated, and many modern cases can be reversed by antibiotics. In medieval Turkey, things were very different.

History

In the Christian year 1510, Bayezid the Second ruled the Ottoman Empire. On the shores of the Black Sea, at the mouth of the Sakarya River, there was a colony for lepers called Saint Augustine's Retreat. The lepers grew barley and made goat cheese. Their needs for commerce with the outside world were met by an adjacent community, the Franciscan monks of The Order of Saint Augustine, who maintained the leprosarium.

Throughout the existence of the colony, it attracted a steady stream of pilgrim lepers, who walked there from as far away as Greece and Persia. In roughly 1520 a new form of Hansen's disease appeared among the pilgrims. The Franciscans called it bone leprosy.

Symptoms

The basic distinction here is easy to grasp. The hallmark symptom of normal leprosy is that necrotic flesh falls from the bones of the extremities. In bone leprosy, the bones of the extremities fall from the flesh.

First the blackened bones of the fingers and toes would poke themselves bloodlessly through the skin and detach. Next the metacarpals and metatarsals disassembled themselves and emigrated. At this stage the victim could still walk on his ankles with the help of crutches. But then the long bones of the four limbs would emerge into the light of day and discard themselves.

The chronicle of Father Ambrosius, the last abbot of The Order of Saint Augustine, reports that one bone leper also lost his pelvis, scapulars, and clavicles, and got along with only a skull, a spine, and some ribs. This man called himself Vecchio Calamaro, "the old squid." He may have been born in Italy.

Further History

By 1530 many bone lepers could be seen among the hovels of the colony, squirming across the earth like giant sea stars. But the "Normal Lepers" distrusted "the Boneless Ones" and finally attacked them with clubs and drove them from the colony.

The Boneless Ones slithered away and formed their own settlement on a barren plateau that overlooked the monastery, the leprosarium, and the river. They drew water from a mountain stream and grew vegetables and spices. At the instruction of Father Ambrosius, the monks brought them barley and milk on the sly. An uneasy truce ensued between the two leper colonies.

In 1534, during the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent, Old Calamaro experienced a religious epiphany. He communicated this vision to his fellow pariahs with such force that they reorganized themselves as a lay brotherhood. They committed their lives to penance, holy poverty, and the contemplation of Christ's mercies. Calamaro went to live in a pit lined with stones, like a shallow well shaft or a lidless oubliette. He dug this pit himself, using only his teeth and a wooden spoon.

As the years progressed, more and more of the Boneless took vows and became visionary hermits, living in the sunken circular cells that dotted the plateau. They seldom spoke, but their echoing chants at dawn and dusk could be heard by Father Ambrosius at Saint Augustine's. Certainly the Boneless Ones had surpassed the Franciscans in their pursuit of austerity. Ambrosius felt no temptation to envy them their accomplishment. (1)

The only existing record of The Order of Saint Augustine and the two leprosariums concludes with the death of Ambrosius. The monastery walls have been toppled by earthquakes.

But Old Calamaro is remembered to this day as Saint Calamaro of the Russian Orthodox Church. A few of the "prayer pits" of his brotherhood have been preserved for visitation near the modern town of Karasu.

Hagiography

A hagiography is not, of course, medical data. I present this excerpt from Saint Calamaro's notwithstanding, freely translated from an anonymous Latin parchment. Please consider it as a curious footnote to the social history of leprosy.

The miracles of Saint Calamaro were three in number, and three in number were his trials, the first being a trial by hunger.

It came to pass that the hearts of the Normal Lepers were enflamed against their bone-bereft neighbors. And the Normals didst resolve to accost those gentle Franciscans who went forth each day to pass among the Boneless. For the Normals deemed it folly to risk contagion from such an unnatural affliction as bonelessness. And they shouted at the monks, saying, "Shun the unclean! Your charity could get us all deboned!"

And they didst smite those humble monks, and lo they broke many heads. For they grew cruel when they got a little wine into them. And Father Ambrosius didst resign himself to abandon the Boneless.

And further the Normals didst rip up the Boneless Ones' gardens and didst foul the pure water of their stream.

For 40 days and nights, the Boneless drank only the morning dew that condensed on the walls of their cells, and ate only the tiny creeping things that they found within their clothes. And yet they thirsted not, nor didst they hunger. For the grace of Saint Calamaro's first miracle was upon them.

The second trial of the saint was a trial by drowning. For indeed the Normals didst arise again against him and didst drag him from his pit. And none of his followers resisted the Normals, but rather they prayed more loudly to drown out his cries for help. For the Boneless were sore afraid.

And in consequence the Normals didst bind the saint within a sack, and drag the sack across sharp rocks to a boat, and row this boat a great distance across the Black Sea. And there they didst abuse the saint and kick him in his private parts and throw him overboard and leave him to drown. And the Normals were well satisfied, even though an ear, a nose, and several of their fingers had been lost in the scuffle.

In his aquatic extremity, the saint lost not his faith in his Savior, but didst call out loudly to the Lord, with many Italianate profanities, in fear and in trembling and with evil-tasting water in his mouth. And his prayers were answered, for like unto the rainbow-dappled jellyfish, he didst float upon the sea, nor did he sink.

The Normals didst row to shore and make straight for their dining hall, for drowning cripples always made them thirsty. And lo the second miracle! At their dining hall, they found their cook in great dismay. For Saint Calamaro had appeared in her largest stew pot and was eating all the stew.

Then the saint's final trial was upon him, which was a trial by boiling in oil. For the outraged Normals didst pour much olive oil into that soup pot and didst clamp down the lid with great force and three carpenter's vices. And they didst convey the soup pot to an open space between their hovels, where they soon amassed the makings for a bonfire. Mightily that conflagration raged about the soup pot. And the Normals danced and shouted, saying, "This is how we cook a squid in Turkey!"

But when the fires died, and the soup pot was opened, there was nothing inside. And just as the Normals saw this ominous emptiness, a chuckling was heard.

And lo the third miracle! It was Old Calamaro. He was inside the dining hall again, feasting on almonds and custards and wine. And seeing this, the Normals didst flee in fright from the doings of this leprous magus.

And though he was never seen again, peace reigned forever after between the Normals and the Boneless. For it was said among them that Old Calamaro had melted into the shingle at the shore, like unto an icicle in the sunshine. And they said that he dwelt now in the earth beneath their sandals, and that he watched all the lepers of the world, lest they ever again mistreat the wretched.

But in truth the Old Squid ascended to the Land of Light and sits now among the choirs of the angels in the throne room of the Lord. Perhaps he even sits on a velvet stool beside the Savior's giant golden throne.

Or perhaps--who can say?--he reclines more comfortably on the white marble floor beneath the throne, peering out from his special place between the four golden legs. Perhaps he reclines on a tasteful Persian rug, eating stewed prunes with a silver spoon. Perhaps he smiles down toothlessly on all the prostrate supplicants arrayed before God's throne. Perhaps he shakes his head and chuckles, as they beg for mercy.

Submitted by

Stepan Chapman, Doctor of Pandemics

Endnote

(1) Father Ambrosius wrote the following scrap of Latin verse into a margin of his chronicle.

Shunned by their unclean brethren,

Who are shunned by the monks of my order,

Who in turn are barely tolerated

By the Moslem that surround us.

Who is the lowliest of the low?

Who is most outcast?

Cross References

Chronic Zygotic Dermis Disorder; Diseasemaker's Croup; Extreme Exostosis; Razornail Bone Rot

Recenzii

“An amazing book … plays delicious postmodernist games that are sure to delight the discerning (and slightly warped) reader.”

—Publishers Weekly

“Lambshead is just what the doctor ordered.”

—Village Voice

—Publishers Weekly

“Lambshead is just what the doctor ordered.”

—Village Voice

Descriere

Offering complete histories, symptom guides, and suggested treatments for rare and fantastical ailments, here is a dose of good humor for every sleep-deprived medical student, overworked physician, hypochondriac, and curious reader.