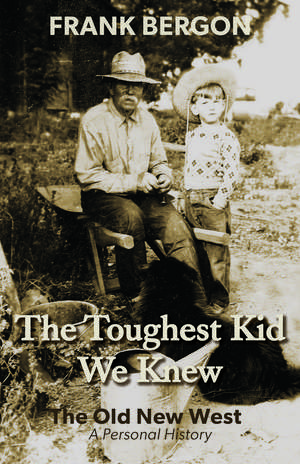

The Toughest Kid We Knew: The Old New West: A Personal History

Autor Frank Bergonen Limba Engleză Hardback – 15 iun 2020 – vârsta ani

From critically acclaimed author Frank Bergon comes a new personal narrative about the San Joaquin Valley in California. This intimate companion to Two-Buck Chuck & The Marlboro Man brings us back to an Old West at odds with New West realities where rapid change is a common trait and memories are of rural beauty. Despite the physical transformations wrought by technology and modernity in the twenty-first century, elements of an older way of thinking still remain, and Bergon traces its presence using experiences from his own family and friends.

Communal camaraderie, love of the land and its food, and joy in hard work done well describe Western lives ignored or misrepresented in most histories of California and the West. Yet nostalgia does not drive Frank Bergon’s intellectual return to that world. Also prevalent was a culture of fighting, ignorance about alcoholic addiction, brutalizing labor, and a feudal mentality that created a pain better lost and bid good riddance.

Through it all, what emerges from his portraits and essays is a revelation of small-town and ranch life in the rural West. A place where the American way of extirpating the past and violently altering the land is accelerated. What Bergon has written is a portrayal of a past and people shaping the country he called home.

Communal camaraderie, love of the land and its food, and joy in hard work done well describe Western lives ignored or misrepresented in most histories of California and the West. Yet nostalgia does not drive Frank Bergon’s intellectual return to that world. Also prevalent was a culture of fighting, ignorance about alcoholic addiction, brutalizing labor, and a feudal mentality that created a pain better lost and bid good riddance.

Through it all, what emerges from his portraits and essays is a revelation of small-town and ranch life in the rural West. A place where the American way of extirpating the past and violently altering the land is accelerated. What Bergon has written is a portrayal of a past and people shaping the country he called home.

Preț: 232.34 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 349

Preț estimativ în valută:

44.46€ • 46.36$ • 36.95£

44.46€ • 46.36$ • 36.95£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781948908641

ISBN-10: 1948908646

Pagini: 208

Ilustrații: 10 b-w photos

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.36 kg

Ediția:First Edition

Editura: University of Nevada Press

Colecția University of Nevada Press

ISBN-10: 1948908646

Pagini: 208

Ilustrații: 10 b-w photos

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.36 kg

Ediția:First Edition

Editura: University of Nevada Press

Colecția University of Nevada Press

Recenzii

Praise for Two-Buck Chuck & The Marlboro Man:

"A tour of the interior West worth taking."

—Kirkus Reviews

"...insightful... Bergon's memories and interviews ground larger historical events..."

—Publishers Weekly

“In 12 prose portraits of people and place, western novelist and historian Bergon portrays the marriage of Old West spirit with New West realities...a way of life and culture he believes to be misunderstood and misreported...Bergon sets this record straight with close-up stories of people with whom he grew up and befriended in the San Joaquin Valley.”

—Booklist

“With a novelist’s fine gifts for character and scene, a historian’s depth of perspective, and a local’s intimate knowledge and love, Frank Bergon leads us through California’s Big Valley, where the past lies entwined with the present and every critical tension in modern America plays out in its most distilled form.”

—Miriam Horn, author of Rancher, Farmer, Fisherman

The Central Valley has produced its share of writers—Maxine Hong Kingston, Leonard Gardiner, Joan Didion, and most famously John Steinbeck, who set much of The Grapes of Wrath in the Valley. Place matters to them all, but none quite so much as Bergon, who might legitimately be called the poet laureate of Central Valley. His powerful evocations reveal how distinctive and interesting it truly was during the middle decades of the twentieth century.

—Western American LiteratureIn elegant prose, Frank Bergon has conjured a complex portrait of the San Joaquin Valley of California during the mid-1950s and beyond, where some 90 distinct ethnic communities lived together for a century, his own valley family being Basque as were his beloved grandparents in Nevada. The Toughest Kid We Knew is one of the best literary memoirs written, focusing on the particular while evoking universal human experience.

—Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, author of Red Dirt: Growing Up Okie

The Toughest Kid We Knew is a magnificent book about the American West and a multigenerational family’s ties to its ancestral homeland and to the daunting land of the San Joaquin Valley. Frank Bergon has delivered a literary bounty. I don’t think a page went by without an observation, insight, or detail that somehow sparked my imagination or stayed with me long after I’d turned the page. I loved spending time with these remarkable people in this unforgettable place.

—Meghan Daum, author of The Problem With Everything: My Journey Through The New Culture Wars

These essays are masterfully crafted.

—Daryl Farmer, author of Where We Land and Bicycling Beyond the Divide

"A tour of the interior West worth taking."

—Kirkus Reviews

"...insightful... Bergon's memories and interviews ground larger historical events..."

—Publishers Weekly

“In 12 prose portraits of people and place, western novelist and historian Bergon portrays the marriage of Old West spirit with New West realities...a way of life and culture he believes to be misunderstood and misreported...Bergon sets this record straight with close-up stories of people with whom he grew up and befriended in the San Joaquin Valley.”

—Booklist

“With a novelist’s fine gifts for character and scene, a historian’s depth of perspective, and a local’s intimate knowledge and love, Frank Bergon leads us through California’s Big Valley, where the past lies entwined with the present and every critical tension in modern America plays out in its most distilled form.”

—Miriam Horn, author of Rancher, Farmer, Fisherman

The Central Valley has produced its share of writers—Maxine Hong Kingston, Leonard Gardiner, Joan Didion, and most famously John Steinbeck, who set much of The Grapes of Wrath in the Valley. Place matters to them all, but none quite so much as Bergon, who might legitimately be called the poet laureate of Central Valley. His powerful evocations reveal how distinctive and interesting it truly was during the middle decades of the twentieth century.

—Western American LiteratureIn elegant prose, Frank Bergon has conjured a complex portrait of the San Joaquin Valley of California during the mid-1950s and beyond, where some 90 distinct ethnic communities lived together for a century, his own valley family being Basque as were his beloved grandparents in Nevada. The Toughest Kid We Knew is one of the best literary memoirs written, focusing on the particular while evoking universal human experience.

—Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, author of Red Dirt: Growing Up Okie

The Toughest Kid We Knew is a magnificent book about the American West and a multigenerational family’s ties to its ancestral homeland and to the daunting land of the San Joaquin Valley. Frank Bergon has delivered a literary bounty. I don’t think a page went by without an observation, insight, or detail that somehow sparked my imagination or stayed with me long after I’d turned the page. I loved spending time with these remarkable people in this unforgettable place.

—Meghan Daum, author of The Problem With Everything: My Journey Through The New Culture Wars

These essays are masterfully crafted.

—Daryl Farmer, author of Where We Land and Bicycling Beyond the Divide

Notă biografică

Frank Bergon is a critically acclaimed novelist, critic, and essayist. His writing mainly focuses on the history and environment of the American West, including his most recent work Two-Buck Chuck & The Marlboro Man. Frank was born in Ely, Nevada, and grew up on a ranch in Madera County in California’s San Joaquin Valley.

Extras

INTRODUCTION

One June night after a late dinner in Oakland, an old friend announced to a group of us, “Your earliest memory will tell you the essential truth of your life.”

We were incredulous. The essential truth of our lives? What did he mean?

He went on: “Your first memory—or the earliest one you can recall—will reveal who you really are, or at least how you see yourself and experience the world. Let’s try it.”

We did. The narration of our earliest memories around the table expanded beyond a parlor game as we discovered past scenes or anecdotes that became to our astonishment more enlightening than expected. We were all friends. We’d known each other for years, meaning, of course, that we had a sharper sense of each other than of ourselves. No one hesitated in choosing an early memory—whether it was literal in every detail didn’t matter. Each memory had the persuasive power of a story believed by the teller. As with all stories of emotional honesty, facts gave way to truths that surprised each of us when further illuminated by the commentary of others around the table.

People’s memories that night conjured up varied childhood experiences: the sense of luck from finding a penny as a child, the thrill of danger at seeing a black widow spider, the sensation of mystery flickering in the shadows above a child’s crib, the feeling of safety while walking with parents under shady sycamores.

I found myself talking for the first time in public about a night when I was a boy in Los Angeles, a child fresh from Nevada, on a dark, sloping lawn of a relative’s house. It was my earliest memory of California. I was alone, involved in some solitary fantastical adventure, when I heard the voices of two older boys at the edge of the lawn near the sidewalk. I barely discerned their figures in the dim light. “Hey, look at this,” one of the boys said. He’d picked up from the grass a wooden sword that my Basque uncle had carved for me in Nevada. It had a handle, hilt, and a curved blade painted yellow—a pirate’s sword. I loved that sword. It was my favorite toy, all the more so because my favorite uncle had made it for me. “Neat,” the other boy said.

I felt panic. “That’s mine,” I yelled.

Then the boys ran. I ran after them, but being bigger and faster they soon disappeared into the night with the sword.

The aftermath fades into dimness. I have a vague sense of myself inside the house telling my parents and relatives what had happened. I must’ve been crying, I must’ve been consoled, although I can’t remember. What I recall is a hazy adult response of general sympathy enlarged by an accepting view about how such things happen in life. What more firmly remains in my mind is the dark expanse of lawn sloping downward—an odd detail for L.A.—into a deeper darkness where the thing I once cherished had now vanished.

At the Oakland dinner party, the expected Freudian interpretation of my story, initiated by one friend, was dismissed by the only professional therapist in the group, who was trained as a Jungian. The larger sense of loss described in this little story varied from person to person around the table. We all hate to lose or break things. We all have a sense of absence for the vanished lives we once lived, and every memory is tinged with its own death, an experience shared to varying degrees by those around the table that night.

When I think of my story about the sword, I recall from my childhood scrapbook a photograph of me in a pirate’s costume for a Halloween party in the high desert town of Battle Mountain, Nevada. My mother took the photo. I don’t remember the moment, but there I am next to my bare-bellied cousin in her veil and gauzy harem pants. A pirate’s bandana covers my head. I’m wearing a blousy shirt and billowy pants. Sticking through the wide sash around my waist is the pirate’s sword my uncle had carved for me. I haven’t looked at the photo for years, but I remember it, and I wonder if without my memory of the photo I would’ve remembered that precious sword and its later loss in the way I have. Our memories, psychologists tell us, are reprints of earlier memories, like photos of photos, one layered on top of the other. What we end up remembering are memories of memories in constant flux.

For years I resisted dredging up early memories of my youth for fear of resurrecting painful experiences or hardening them into false stories. I make this admission of evasion with some regret. Because I didn’t want my memories rigidified or shaped too quickly by negative feelings, I may have abandoned much of the past. Now that I’ve written the story of that night in California when the sword was stolen, I realize I was recounting the story as I’d narrated it to my friends in Oakland—with a few added recollections. What I’ll now continue to remember, I know, is not the night as it happened—that’s lost—but as it’s dramatized in the words of the story I’ve written.

Sometimes in my dreams I hear the voices of my mother or father with such intensity that I’m startled upon awakening to discover that my parents are dead. Such dreams in their sound and motion can generate an emotional truthfulness beyond the factual accuracy of photographs. In the profiles and essays that follow, I’ve tried to offer glimpses of a way of life on ranches and small towns of the mid-twentieth century, put into motion and sound through their telling with something of a dream’s truth. As the past bubbled to mind with certain long-ago events I hadn’t thought of in years, I sensed something akin to the claim of the eighteenth-century writer Thomas De Quincey: “Of this, at least, I feel assured, that there is no such thing as forgetting possible to the mind.”

To preserve against loss or to recover lost events, lost histories, and lost stories is what writers do, whether one is Willa Cather in New York City remembering the Great Plains of her childhood in A Lost Lady or a Frenchman in a fifth-floor Paris apartment fashioning seven volumes In Search of Lost Time. To write as a way of discovery and preservation can give glimpses into the felt texture of other lives, as I realized that night in Oakland when facts shared with those around a table grew into unexpected truths.

My concern in this book is primarily with California’s San Joaquin Valley, in the center of the state, where I grew up on my Béarnais American grandfather’s Madera County ranch, defined as a Westerner. I wrote about this valley in an earlier book, Two-Buck Chuck & The Marlboro Man: The New Old West, as a place where frontier values shared by a multiracial and multiethnic population gave the valley its distinctive character and in many ways continue to do so beyond the physical transformations of technology and modernity in the twenty-first century. In this companion book, I move back in time to write about my own family and boyhood community, people whose stories also include a variety of immigrants and migrants, as well as their offspring, many shaped as I was in small towns and on family ranches. What follows isn’t an autobiography or a traditional memoir. It’s an attempt through personal essays and profiles of people I’ve known, including my own family, to help understand how it felt and what it meant to be alive in a particular community at a particular time. I soon discovered that I was writing about something else: Western life ignored or misrepresented in most histories of California and the West. In a time calling for an understanding of rural America, what emerges for me in these stories is a way of life that continues to be dismissed or remain invisible in the larger culture. These are stories of rural and small-town Westerners, who helped shape California, the New West, and America itself, people whose stories point to how those from rural America think and feel today.

The California of my boyhood led the way in making the “New West” a place of suburban tract ranch homes, shopping centers, supermarkets, drive-in theaters, and trend-setting clothes, including Levi’s with copper rivets originally invented for working men by a Latvian Jewish immigrant and a California company a hundred years earlier. "Don’t Californicate Our State," other Westerners hollered. But it was useless. California, as the extreme West, showed the way the urban-and-suburban West was going and simply got there first. The Santa Clara Valley, where I went to high school, was a region of flowering fruit trees nicknamed Valley of Heart’s Delight before it dissolved into Silicon Valley, where overpriced real estate, computer chips, and start-ups replaced apricots and cherries in the latest rush for gold. The rural San Joaquin Valley remained a place where the lingering Old West intersected with the New West. Now viewed from the twenty-first century, the valley of my boyhood appears in sepia hues as the Old New West.

Other people’s voices and memories appear in this portrayal of the West, as noted in the “We” of the book’s title. In their stories, both old-timers and newcomers in this book relate overlapping experiences and shared beliefs. My immigrant Basque grandmother in Nevada shares something with the migrant Okie we knew as the toughest kid in the valley. Indarra is the word in Euskara applied to my grandmother and other Basques for their persistence, endurance, and strength. Toughness as a primary virtue is what Okie boys and girls understood not simply as physical strength for fighting and work but an ability to endure. My California-born grandfather, who was a tenant farmer in the early twentieth century, could talk with a migrant African American landowner and an immigrant fieldworker fifty years later because they shared a belief in the rewards of perseverance, an allegiance to Western dreams of freedom and opportunity, and an expectation of diversity and porous social-class boundaries, all co-existing with an abiding acceptance of disappointment.

My old writing teacher at Stanford, Wallace Stegner, once said, “I suspect that a sharecropper and a banker in Charlotte, North Carolina, have more in common than a banker in North Carolina and a banker in Redwood City.” Stegner was talking about a shared regional culture as an important force in our lives. It certainly was when my father and aunt went to a valley school whose pupils represented a mixed heritage of Japanese, Italian, German, Mexican, Chinese, Basque, Béarnais, African, Assyrian, Swedish, Portuguese, Russian, and Armenian, born inside or outside the state, though all Californians, whose view of themselves didn’t stop at the border. Connections remained even for me with relatives in Nevada, the Basque Country, and Béarn. Others of my generation give accounts of the porous social borders we lived in, as when the son of a Jewish doctor made his first visit to a classmate’s home that turned out to be at a labor tent camp. The valley remains one of the most racially and ethnically rich areas in the country, but Stegner’s claim of a shared culture and mine of shared experiences have less verity in the current valley of gated communities and suburban isolation.

As a descendant of immigrants, I’m aware of how the valley’s diverse population can challenge conventional views of California and the West. As a ranch boy, I’m aware of how the valley’s many family farms can upend the stereotype of corporate factories in the field. The rural values that emerge in this book sometimes created a shared cultural environment, as Stegner suggested, but a region is composed of both cultural and physical environments that intertwine. We don’t know much about the formative power of our physical environment. At least I don’t. We know more about how we shape it than about how it shapes us. Sometimes presented as trivial examples of the power of place are the regional flavors of bagels, sourdough bread, wine, and cigars, which may not be so trivial after all. In the smells and sounds of the ranch air where I lived as a boy I felt the physical power of the land as an active agent in my life. Atmospheric changes weren’t just shifts in weather but expressions of the land’s spirit, something I felt but didn’t realize until I moved away and the natural world began to function as a character in my novels—maybe the chief character—and their source of value.

Today a way of thinking remains in the valley, renewed as in the past by immigrants and migrants, but a particular rural experience is gone. Rapid change is a common trait writers ascribe to the San Joaquin Valley and to California itself. There the American way of extirpating the past and violently altering the land is accelerated. California remains home to some people, like my sisters, while to others it’s a place to live without ever feeling at home. Or it’s a former home, as for my brother and me. Nostalgia doesn’t drive my return to that world. Some things in the past were better, some weren’t. In the paternalistic ranch world where I grew up, a culture of fighting, ignorance about alcoholic addiction, brutalizing labor, and a feudal mentality created much pain better lost and bid good riddance. Memories also remain of rural beauty, small-town camaraderie, fair play, love of the land, enjoyment of its food, and joy in hard work done well. What I write is a personal history of a past and people shaping the country I called home.

One June night after a late dinner in Oakland, an old friend announced to a group of us, “Your earliest memory will tell you the essential truth of your life.”

We were incredulous. The essential truth of our lives? What did he mean?

He went on: “Your first memory—or the earliest one you can recall—will reveal who you really are, or at least how you see yourself and experience the world. Let’s try it.”

We did. The narration of our earliest memories around the table expanded beyond a parlor game as we discovered past scenes or anecdotes that became to our astonishment more enlightening than expected. We were all friends. We’d known each other for years, meaning, of course, that we had a sharper sense of each other than of ourselves. No one hesitated in choosing an early memory—whether it was literal in every detail didn’t matter. Each memory had the persuasive power of a story believed by the teller. As with all stories of emotional honesty, facts gave way to truths that surprised each of us when further illuminated by the commentary of others around the table.

People’s memories that night conjured up varied childhood experiences: the sense of luck from finding a penny as a child, the thrill of danger at seeing a black widow spider, the sensation of mystery flickering in the shadows above a child’s crib, the feeling of safety while walking with parents under shady sycamores.

I found myself talking for the first time in public about a night when I was a boy in Los Angeles, a child fresh from Nevada, on a dark, sloping lawn of a relative’s house. It was my earliest memory of California. I was alone, involved in some solitary fantastical adventure, when I heard the voices of two older boys at the edge of the lawn near the sidewalk. I barely discerned their figures in the dim light. “Hey, look at this,” one of the boys said. He’d picked up from the grass a wooden sword that my Basque uncle had carved for me in Nevada. It had a handle, hilt, and a curved blade painted yellow—a pirate’s sword. I loved that sword. It was my favorite toy, all the more so because my favorite uncle had made it for me. “Neat,” the other boy said.

I felt panic. “That’s mine,” I yelled.

Then the boys ran. I ran after them, but being bigger and faster they soon disappeared into the night with the sword.

The aftermath fades into dimness. I have a vague sense of myself inside the house telling my parents and relatives what had happened. I must’ve been crying, I must’ve been consoled, although I can’t remember. What I recall is a hazy adult response of general sympathy enlarged by an accepting view about how such things happen in life. What more firmly remains in my mind is the dark expanse of lawn sloping downward—an odd detail for L.A.—into a deeper darkness where the thing I once cherished had now vanished.

At the Oakland dinner party, the expected Freudian interpretation of my story, initiated by one friend, was dismissed by the only professional therapist in the group, who was trained as a Jungian. The larger sense of loss described in this little story varied from person to person around the table. We all hate to lose or break things. We all have a sense of absence for the vanished lives we once lived, and every memory is tinged with its own death, an experience shared to varying degrees by those around the table that night.

When I think of my story about the sword, I recall from my childhood scrapbook a photograph of me in a pirate’s costume for a Halloween party in the high desert town of Battle Mountain, Nevada. My mother took the photo. I don’t remember the moment, but there I am next to my bare-bellied cousin in her veil and gauzy harem pants. A pirate’s bandana covers my head. I’m wearing a blousy shirt and billowy pants. Sticking through the wide sash around my waist is the pirate’s sword my uncle had carved for me. I haven’t looked at the photo for years, but I remember it, and I wonder if without my memory of the photo I would’ve remembered that precious sword and its later loss in the way I have. Our memories, psychologists tell us, are reprints of earlier memories, like photos of photos, one layered on top of the other. What we end up remembering are memories of memories in constant flux.

For years I resisted dredging up early memories of my youth for fear of resurrecting painful experiences or hardening them into false stories. I make this admission of evasion with some regret. Because I didn’t want my memories rigidified or shaped too quickly by negative feelings, I may have abandoned much of the past. Now that I’ve written the story of that night in California when the sword was stolen, I realize I was recounting the story as I’d narrated it to my friends in Oakland—with a few added recollections. What I’ll now continue to remember, I know, is not the night as it happened—that’s lost—but as it’s dramatized in the words of the story I’ve written.

Sometimes in my dreams I hear the voices of my mother or father with such intensity that I’m startled upon awakening to discover that my parents are dead. Such dreams in their sound and motion can generate an emotional truthfulness beyond the factual accuracy of photographs. In the profiles and essays that follow, I’ve tried to offer glimpses of a way of life on ranches and small towns of the mid-twentieth century, put into motion and sound through their telling with something of a dream’s truth. As the past bubbled to mind with certain long-ago events I hadn’t thought of in years, I sensed something akin to the claim of the eighteenth-century writer Thomas De Quincey: “Of this, at least, I feel assured, that there is no such thing as forgetting possible to the mind.”

To preserve against loss or to recover lost events, lost histories, and lost stories is what writers do, whether one is Willa Cather in New York City remembering the Great Plains of her childhood in A Lost Lady or a Frenchman in a fifth-floor Paris apartment fashioning seven volumes In Search of Lost Time. To write as a way of discovery and preservation can give glimpses into the felt texture of other lives, as I realized that night in Oakland when facts shared with those around a table grew into unexpected truths.

My concern in this book is primarily with California’s San Joaquin Valley, in the center of the state, where I grew up on my Béarnais American grandfather’s Madera County ranch, defined as a Westerner. I wrote about this valley in an earlier book, Two-Buck Chuck & The Marlboro Man: The New Old West, as a place where frontier values shared by a multiracial and multiethnic population gave the valley its distinctive character and in many ways continue to do so beyond the physical transformations of technology and modernity in the twenty-first century. In this companion book, I move back in time to write about my own family and boyhood community, people whose stories also include a variety of immigrants and migrants, as well as their offspring, many shaped as I was in small towns and on family ranches. What follows isn’t an autobiography or a traditional memoir. It’s an attempt through personal essays and profiles of people I’ve known, including my own family, to help understand how it felt and what it meant to be alive in a particular community at a particular time. I soon discovered that I was writing about something else: Western life ignored or misrepresented in most histories of California and the West. In a time calling for an understanding of rural America, what emerges for me in these stories is a way of life that continues to be dismissed or remain invisible in the larger culture. These are stories of rural and small-town Westerners, who helped shape California, the New West, and America itself, people whose stories point to how those from rural America think and feel today.

The California of my boyhood led the way in making the “New West” a place of suburban tract ranch homes, shopping centers, supermarkets, drive-in theaters, and trend-setting clothes, including Levi’s with copper rivets originally invented for working men by a Latvian Jewish immigrant and a California company a hundred years earlier. "Don’t Californicate Our State," other Westerners hollered. But it was useless. California, as the extreme West, showed the way the urban-and-suburban West was going and simply got there first. The Santa Clara Valley, where I went to high school, was a region of flowering fruit trees nicknamed Valley of Heart’s Delight before it dissolved into Silicon Valley, where overpriced real estate, computer chips, and start-ups replaced apricots and cherries in the latest rush for gold. The rural San Joaquin Valley remained a place where the lingering Old West intersected with the New West. Now viewed from the twenty-first century, the valley of my boyhood appears in sepia hues as the Old New West.

Other people’s voices and memories appear in this portrayal of the West, as noted in the “We” of the book’s title. In their stories, both old-timers and newcomers in this book relate overlapping experiences and shared beliefs. My immigrant Basque grandmother in Nevada shares something with the migrant Okie we knew as the toughest kid in the valley. Indarra is the word in Euskara applied to my grandmother and other Basques for their persistence, endurance, and strength. Toughness as a primary virtue is what Okie boys and girls understood not simply as physical strength for fighting and work but an ability to endure. My California-born grandfather, who was a tenant farmer in the early twentieth century, could talk with a migrant African American landowner and an immigrant fieldworker fifty years later because they shared a belief in the rewards of perseverance, an allegiance to Western dreams of freedom and opportunity, and an expectation of diversity and porous social-class boundaries, all co-existing with an abiding acceptance of disappointment.

My old writing teacher at Stanford, Wallace Stegner, once said, “I suspect that a sharecropper and a banker in Charlotte, North Carolina, have more in common than a banker in North Carolina and a banker in Redwood City.” Stegner was talking about a shared regional culture as an important force in our lives. It certainly was when my father and aunt went to a valley school whose pupils represented a mixed heritage of Japanese, Italian, German, Mexican, Chinese, Basque, Béarnais, African, Assyrian, Swedish, Portuguese, Russian, and Armenian, born inside or outside the state, though all Californians, whose view of themselves didn’t stop at the border. Connections remained even for me with relatives in Nevada, the Basque Country, and Béarn. Others of my generation give accounts of the porous social borders we lived in, as when the son of a Jewish doctor made his first visit to a classmate’s home that turned out to be at a labor tent camp. The valley remains one of the most racially and ethnically rich areas in the country, but Stegner’s claim of a shared culture and mine of shared experiences have less verity in the current valley of gated communities and suburban isolation.

As a descendant of immigrants, I’m aware of how the valley’s diverse population can challenge conventional views of California and the West. As a ranch boy, I’m aware of how the valley’s many family farms can upend the stereotype of corporate factories in the field. The rural values that emerge in this book sometimes created a shared cultural environment, as Stegner suggested, but a region is composed of both cultural and physical environments that intertwine. We don’t know much about the formative power of our physical environment. At least I don’t. We know more about how we shape it than about how it shapes us. Sometimes presented as trivial examples of the power of place are the regional flavors of bagels, sourdough bread, wine, and cigars, which may not be so trivial after all. In the smells and sounds of the ranch air where I lived as a boy I felt the physical power of the land as an active agent in my life. Atmospheric changes weren’t just shifts in weather but expressions of the land’s spirit, something I felt but didn’t realize until I moved away and the natural world began to function as a character in my novels—maybe the chief character—and their source of value.

Today a way of thinking remains in the valley, renewed as in the past by immigrants and migrants, but a particular rural experience is gone. Rapid change is a common trait writers ascribe to the San Joaquin Valley and to California itself. There the American way of extirpating the past and violently altering the land is accelerated. California remains home to some people, like my sisters, while to others it’s a place to live without ever feeling at home. Or it’s a former home, as for my brother and me. Nostalgia doesn’t drive my return to that world. Some things in the past were better, some weren’t. In the paternalistic ranch world where I grew up, a culture of fighting, ignorance about alcoholic addiction, brutalizing labor, and a feudal mentality created much pain better lost and bid good riddance. Memories also remain of rural beauty, small-town camaraderie, fair play, love of the land, enjoyment of its food, and joy in hard work done well. What I write is a personal history of a past and people shaping the country I called home.

Cuprins

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction

Part I: On the Ranch

My Basque Grandmother

Old Man Prosper

Reading Steinbeck

Seeing the Mountains

The Basque Nurse

The FBI Rancher

Magic in Cowboy Country

My L.A. Relatives

Part II: In the Valley

The Displaced Béarnais

King of the San Joaquin

Rose in a Country of Men

Chief Kit Fox Revisited

Reading Didion

Black Farm Kid and the Okies

The Toughest Kid We Knew

Basque Family Style

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Introduction

Part I: On the Ranch

My Basque Grandmother

Old Man Prosper

Reading Steinbeck

Seeing the Mountains

The Basque Nurse

The FBI Rancher

Magic in Cowboy Country

My L.A. Relatives

Part II: In the Valley

The Displaced Béarnais

King of the San Joaquin

Rose in a Country of Men

Chief Kit Fox Revisited

Reading Didion

Black Farm Kid and the Okies

The Toughest Kid We Knew

Basque Family Style

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Descriere

Frank Bergon’s newest work is a thoughtful exploration of the ways that memories of random childhood events become unexpected revelations about life in the West. In many senses this project is a personalized version of Two-Buck Chuck & The Marlboro Man where Bergon explored the ways that a multiethnic and multiracial society shaped, and continues to shape, the day-to-day lived realities of the residents and communities of the San Joaquin Valley. Bergon’s latest book creation, however, is more elegiac in tone, paying tribute to ranching and farming lives that are disappearing under suburban and exurban sprawl, industrial farming, and white-collar job growth.