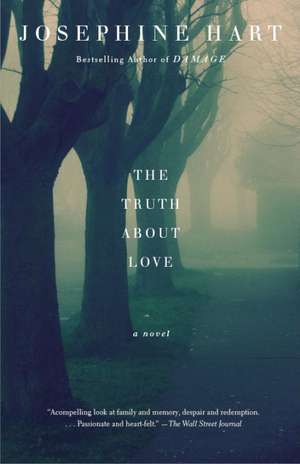

The Truth about Love

Autor Josephine Harten Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 iul 2010

A brilliant meditation on love, loss, and the beauty of living even when times are tough, The Truth About Love shows us how men and women are shaped by tragedy, by their inherent characters, and by what they are able to learn from one another.

Preț: 81.42 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 122

Preț estimativ în valută:

15.58€ • 16.92$ • 13.09£

15.58€ • 16.92$ • 13.09£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307474261

ISBN-10: 0307474267

Pagini: 205

Dimensiuni: 133 x 206 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 0307474267

Pagini: 205

Dimensiuni: 133 x 206 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Notă biografică

Josephine Hart is the best-selling author of Damage, Sin, Oblivion, The Stillest Day, and The Reconstructionist. Her work has been translated into twenty-seven languages. She lives in London with her husband, Maurice Saatchi, and their two sons.

Extras

ONE

. . . today, June 18th, 1962, I, Thomas Middlehoff, known locally as “the German,” attend my first Irish funeral. My housekeeper, Bridget, informed me that there would be no objection. The iconography of this particular death and burial is an unfamiliar one in this place that has known peace for decades. As in all such towns there are recognised routes to eternity: the heart that fails; the cells that in either boredom or rebellion rise up against their host and triumph; the accidental tumble over the edge of life in cars or on bicycles; the exhausted surrender to the sudden storm on water, which “tossed the boat around like . . .”—the metaphor is always dramatic. All these routes eventually seem to have been preordained. This one does not.

The intensity of heat that yesterday had so startled this small town in Ireland has today abated somewhat. The sun shines but its light is now less troubling. The day is warm but it no longer soars in triumph as though it had wished to teach an uncomfortable lesson to those who had failed to factor its burning rays into their sartorial decisions.

The cathedral is full. Mourners who’d arrived too late to be seated huddle in the aisles, some leaning against the confessional boxes in which they normally kneel in darkness. I stand at the back and carefully follow the proceedings in a missal loaned to me by Bridget. It had been handed to me with an air of solemnity, as though it were an ancient letter of introduction that would guarantee safe passage to its recipient. Bridget herself had received it from her grandmother, no doubt with equal solemnity. Bridget has two missals. The new one, a gift from her son, has, perhaps due to a generational imperative, supplanted in importance the older gift which, nevertheless, I was honour-bound to return to her after the funeral.

The ritual of mass begins with the sign of the cross, the ultimate emblem of the sacrifice that mass celebrates. So that no one need doubt its significance, the sign of the cross is made no fewer than fifty-two times during the ceremony. Bridget’s son had evidently counted them once at a Sunday mass, a fact that, though it impressed Bridget greatly, implied to me that this was not a boy in whom resided excessive reverence.

This is a Mass for the dead. Bridget has explained to me that as such it is shorter, due to the omission of certain psalms, “Judica me,” which Bridget had quoted to me with such feeling I had later turned to it in the missal and memorised it. “For Thou art my strength; Why hast Thou cast me off? And why do I go sorrowful whilst the enemy afflicteth me?” It is magnificent. Its omission is appropriate. I concentrate on my missal and after some time I note a certain stirring in the congregation. Slowly the mourners stand up and move from their pews. Someone behind me whispers “offerings.” An orderly queue is formed and men—mostly, I would guess from their age and bearing, the heads of families—are joined by a number of women who shuffle forward with lowered faces, clutching large handbags to them as though they were an aid to gender identification. A number of the men hold white envelopes clasped tightly in their hands and stare straight ahead. Others have placed their envelope carefully in a jacket pocket from which it slightly protrudes, like the edge of a carefully ironed handkerchief.

All move forward silently until they stand before Tom O’Hara and Father Dwyer who are positioned together behind a dark carved-wood table. This has been placed to the left of a small side chapel, in which, on a high bier, the body of Tom O’Hara’s son lies in its coffin. Each man hands over his envelope, his offering. I note all this as I too make my way forward, as Bridget had told me would be expected of me. When it is finally my turn to stand before this man, this bereaved father, Tom O’Hara, I do not look at him. I had noted from their bowed heads that those in front of me had also failed this test of courage. His “thank you” is muffled. It’s a strange gratitude. Bridget had informed me that all monies go to the Parish and that the amount collected is, in a sense, a measure of the sympathy and grief. Measure for measure. As I walk back to my pew I observe Mrs. O’Hara and her daughter and son sitting in the front pew. They sit motionless, isolated in a place of honour no one begrudges them.

Then it is over. Everyone stands. Family and relatives now make their way to the side chapel. To bear witness, no doubt, as the coffin is borne out to the waiting hearse on the shoulders of men, among them his father. Mourners scatter; the men scurry, heads down, towards their cars. Their wives walk slowly, smartly dressed, suits mostly though it is a summer day, heads adorned with discreet hats, mantillas on the heads of the younger women. Car doors open and close with care. Noise cannot be borne today. Everyone, even children, senses the need for quietness.

I decide that I too will walk behind the hearse. It is, I feel, correct that I should do so. It is appropriate. And so the long, slow procession trails its way through the town in which today, for this cortège, every shop has closed. Had it been a state funeral it could not have been more evocative of a dignified expression of grief. At last, perhaps after forty minutes, we arrive at the graveyard, one of mankind’s most underrated symbols of civilisation. A small graveyard is a most particular resting place. It is a place in which the dead may nestle but do not mingle. Here, in this Irish cemetery, the mass grave is unknown. A certain propriety maintains.

As the coffin of the boy is lowered there is a dangerous moment. The boy’s sister seems to sway forwards toward the open grave. In a second she is caught. A priest places his hands, with some force, on her shoulders and steadies her. Separation of the dead from the living often requires strength. Another continues with the prayers.

A handful of earth is thrown over the coffin and the process of filling in a grave commences. After some time mourners begin to drift away. I look around awkwardly, aware that Dr. Carter is in conversation with Father Dwyer and that Bishop Fullerton is speaking quietly to Mr. O’Hara. I am an observer and a stranger, the one I feel almost essential to the other. The elective outsider, the truthful observer of the scene requires an anatomical eye, which I have endeavoured over the years to develop.

My eye now meets that of another, it is caught and trapped for a moment by that of Mrs. O’Hara. There is no escape from it. Her eye is a cold eye, unblinking, frozen perhaps in a memory of what it has witnessed. I take a step toward her but she turns away. I am released into freefall.

Then the vision comes unbidden. Why does the mind allow intrusion against our will? I saw her falling. I saw my mother falling. She did not fall in parts. She fell in her entirety through a powder of the dove-grey dust of shattered masonry. The white-grey stone leg of the statue of a tall young man fell with her. The subtle difference in the shades of white and grey that day delineated contours as sharply as crimson on a black background. The stone boy had stood sentinel in the long colonnade that connected the drawing room to the conservatory. He had been a reliable companion in the childhood games I had played with my brother. He had been just. He had never taken sides. The conservatory, I remember, did not disintegrate that day. Such anomalies are more common in the aftermath of bombing than one might imagine. My mother had just left the drawing room and was, in her last minutes, close to her stone companion who, heroically, fell with her, his leg the first dismembering, then the second, his arm. It broke off in an arc and for a moment it seemed as though he threw it towards her —as if to say, “Take it, take it! Cling to this, this part of me that I offer to you.” Then the falling, fast. The vision dies. And I am here, again, in this place. At an Irish funeral, my first Irish funeral.

Bishop Fullerton now approaches Mrs. O’Hara. He talks to her. Rather, he talks at her. She simply looks at him. Does he also feel trapped? He steps back from her slightly. I move forwards. Each of us is wrong. She turns away and toward her husband. It’s time to go home. Tom O’Hara guides her away. Mourners separate to make a path for them. Priest and bishop stand aside for them. Their grief takes precedence over the normal hierarchical structure of this community. Murmuring quietly, a procession follows them. Some scatter to left or right to stand by other graves. Eamonn, the bishop’s driver, who takes him to and from my house for our chess evenings, approaches me. Would I like to go with the bishop to the O’Haras’ house? I am uncertain whether this invitation comes from Bishop Fullerton or from the O’Hara family. I decline. I will walk home. Though hours remain this day is over.

TWO

It is not true that I discourage visitors from Lake House. It is, however, true that I do not issue invitations. I exclude from this assessment my monthly chess game with Robert Carter and, on separate evenings, with Bishop Fullerton. Since this is a surprisingly formal society I am untroubled by any intrusion by townspeople, other than those who make the three-mile journey for the not necessarily companionable purpose of earning their living.

There exists between myself and Bridget, my non-resident housekeeper, respect, tolerance, and on her part determination that Irish charm will eventually wear me down and I will, “like all strangers who come here, Mr. Middlehoff, fall in love with the place.” Her use of my name is in its own way an act of intimacy, since I am aware that in the town they simply call me “the German.” As a statement of exclusion this is as accurate as it is definitive. It is one I welcome. I believe I carry with me what every German carries with them, an aura, an emanation. I am German. You know me. I regard myself as under an obligation in this matter. “That this is done shall stand for ever more.” And a day. I am mindful of my responsibility as a member of a cursed tribe. In Ireland there is of course no “te absolvo.” There is, however, little interest in a story of evil that the Irish do not fully believe possible. For had they known the truth, some slight readjustment to their view of their own modern history might have been necessary. The moral demands, even of peripheral images, might have blurred the purity of their ancient vision. However, I continue to appreciate a certain discretion concerning the history of my country that I had not found elsewhere in my exile.

Though I remain sensible to my inclusion almost two months ago in the congregation of mourners at the funeral of the boy, I do not seek, nor have I been offered, further integration. Robert Carter, whose medical attendance on the day of the accident had been in a sense accidental, has also retreated to the comparatively isolated position of Protestant doctor in an Irish town. My friendship with him, a former Major in the Medical Corps of the British Army, is no doubt mysterious to them. Perhaps they are convinced that it is based solely on a passion for the game of chess, a game for which their temperament renders them wholly unsuited. As I wonder whether my father would agree with this judgement I hear the sound of a car on gravel and, looking from my study window, see Tom O’Hara emerge from his battered Morris Minor like a man who had been trapped too long in a small cupboard and must now carefully test the limbs that had been forced into abnormal contortions. He looks around and then, it seems, straight at me as I stand by the window. I have no alternative but to leave my study and proceed down the long parquet-floored hall towards the dark oak door that separates me from this uninvited guest. I open my heavy door, slowly.

“Good morning Mr. Middlehoff. I’ve come about the gate.”

“Good morning Mr. O’Hara.”

“Good morning Mr. Middlehoff,” he says again. And again, “I’ve come about the gate.”

The note is abrupt, even peremptory. How am I to respond? This man, whose rather leonine head and large body speak to a slower, calmer nature, is now in a place I recognise and I know the price the terrain exacts. Courtesy, absolute courtesy is now required. It is a balm and today I apply it for my own protection as well as his.

“Which gate, Mr. O’Hara? Which gate? I’m sorry, Mr. O’Hara, but I do not know to what you refer.”

“Didn’t your estate manager, Tim, mention it?”

“No.”

“I asked him to. You’re sure he didn’t mention it?”

“I am sure.”

“Well then I’m sorry. I wouldn’t be here otherwise.”

“No?”

“Do you think I would just turn up at a stranger’s house, Mr. Middlehoff? Just turn up here and ask him for a gate? Is that what you think of us? Is that the kind of people you think we are?”

“I’m sorry, Mr. O’Hara. This a surprising visit and a most surprising request. As for Tim, he is spending a week in Wexford.”

“In Wexford?”

“Yes.”

“Must be the sister then.”

“Yes.”

“Well, well! The gate. The one with the helmet on the top. You know the one: it marks the end of Lake Lane. You brought it here. Took down Edmund Pennington’s old wooden gate.”

“I know the gate, Mr. O’Hara. It marks the perimeter of my land. So indeed I know the gate.”

“Of course you do. It’s yours! Well, I want to buy it from you.”

“You wish to purchase my gate from me? Why?”

“My son, the lad, admired it. Saw it all the time when he waited in the club rowing boat for the island swimmers to be ready. Gazed at it, told me he made up stories about it. Said it was a warrior’s gate because of the carved helmet at the top. He was at that age. Warriors, heroes, you know.”

And I remember my last conversation with the boy.

“I know what you mean and may I again, Mr. O’Hara, express my deepest sympathy to you and your family.”

“Thank you. Thank you. I’m aware it’s a very strange request.”

“It is, Mr. O’Hara.”

“I’ve got it in my head no other gate will do.”

“That is something that often happens. Will you please come in, Mr. O’Hara? Coffee, perhaps?”

From the Hardcover edition.

. . . today, June 18th, 1962, I, Thomas Middlehoff, known locally as “the German,” attend my first Irish funeral. My housekeeper, Bridget, informed me that there would be no objection. The iconography of this particular death and burial is an unfamiliar one in this place that has known peace for decades. As in all such towns there are recognised routes to eternity: the heart that fails; the cells that in either boredom or rebellion rise up against their host and triumph; the accidental tumble over the edge of life in cars or on bicycles; the exhausted surrender to the sudden storm on water, which “tossed the boat around like . . .”—the metaphor is always dramatic. All these routes eventually seem to have been preordained. This one does not.

The intensity of heat that yesterday had so startled this small town in Ireland has today abated somewhat. The sun shines but its light is now less troubling. The day is warm but it no longer soars in triumph as though it had wished to teach an uncomfortable lesson to those who had failed to factor its burning rays into their sartorial decisions.

The cathedral is full. Mourners who’d arrived too late to be seated huddle in the aisles, some leaning against the confessional boxes in which they normally kneel in darkness. I stand at the back and carefully follow the proceedings in a missal loaned to me by Bridget. It had been handed to me with an air of solemnity, as though it were an ancient letter of introduction that would guarantee safe passage to its recipient. Bridget herself had received it from her grandmother, no doubt with equal solemnity. Bridget has two missals. The new one, a gift from her son, has, perhaps due to a generational imperative, supplanted in importance the older gift which, nevertheless, I was honour-bound to return to her after the funeral.

The ritual of mass begins with the sign of the cross, the ultimate emblem of the sacrifice that mass celebrates. So that no one need doubt its significance, the sign of the cross is made no fewer than fifty-two times during the ceremony. Bridget’s son had evidently counted them once at a Sunday mass, a fact that, though it impressed Bridget greatly, implied to me that this was not a boy in whom resided excessive reverence.

This is a Mass for the dead. Bridget has explained to me that as such it is shorter, due to the omission of certain psalms, “Judica me,” which Bridget had quoted to me with such feeling I had later turned to it in the missal and memorised it. “For Thou art my strength; Why hast Thou cast me off? And why do I go sorrowful whilst the enemy afflicteth me?” It is magnificent. Its omission is appropriate. I concentrate on my missal and after some time I note a certain stirring in the congregation. Slowly the mourners stand up and move from their pews. Someone behind me whispers “offerings.” An orderly queue is formed and men—mostly, I would guess from their age and bearing, the heads of families—are joined by a number of women who shuffle forward with lowered faces, clutching large handbags to them as though they were an aid to gender identification. A number of the men hold white envelopes clasped tightly in their hands and stare straight ahead. Others have placed their envelope carefully in a jacket pocket from which it slightly protrudes, like the edge of a carefully ironed handkerchief.

All move forward silently until they stand before Tom O’Hara and Father Dwyer who are positioned together behind a dark carved-wood table. This has been placed to the left of a small side chapel, in which, on a high bier, the body of Tom O’Hara’s son lies in its coffin. Each man hands over his envelope, his offering. I note all this as I too make my way forward, as Bridget had told me would be expected of me. When it is finally my turn to stand before this man, this bereaved father, Tom O’Hara, I do not look at him. I had noted from their bowed heads that those in front of me had also failed this test of courage. His “thank you” is muffled. It’s a strange gratitude. Bridget had informed me that all monies go to the Parish and that the amount collected is, in a sense, a measure of the sympathy and grief. Measure for measure. As I walk back to my pew I observe Mrs. O’Hara and her daughter and son sitting in the front pew. They sit motionless, isolated in a place of honour no one begrudges them.

Then it is over. Everyone stands. Family and relatives now make their way to the side chapel. To bear witness, no doubt, as the coffin is borne out to the waiting hearse on the shoulders of men, among them his father. Mourners scatter; the men scurry, heads down, towards their cars. Their wives walk slowly, smartly dressed, suits mostly though it is a summer day, heads adorned with discreet hats, mantillas on the heads of the younger women. Car doors open and close with care. Noise cannot be borne today. Everyone, even children, senses the need for quietness.

I decide that I too will walk behind the hearse. It is, I feel, correct that I should do so. It is appropriate. And so the long, slow procession trails its way through the town in which today, for this cortège, every shop has closed. Had it been a state funeral it could not have been more evocative of a dignified expression of grief. At last, perhaps after forty minutes, we arrive at the graveyard, one of mankind’s most underrated symbols of civilisation. A small graveyard is a most particular resting place. It is a place in which the dead may nestle but do not mingle. Here, in this Irish cemetery, the mass grave is unknown. A certain propriety maintains.

As the coffin of the boy is lowered there is a dangerous moment. The boy’s sister seems to sway forwards toward the open grave. In a second she is caught. A priest places his hands, with some force, on her shoulders and steadies her. Separation of the dead from the living often requires strength. Another continues with the prayers.

A handful of earth is thrown over the coffin and the process of filling in a grave commences. After some time mourners begin to drift away. I look around awkwardly, aware that Dr. Carter is in conversation with Father Dwyer and that Bishop Fullerton is speaking quietly to Mr. O’Hara. I am an observer and a stranger, the one I feel almost essential to the other. The elective outsider, the truthful observer of the scene requires an anatomical eye, which I have endeavoured over the years to develop.

My eye now meets that of another, it is caught and trapped for a moment by that of Mrs. O’Hara. There is no escape from it. Her eye is a cold eye, unblinking, frozen perhaps in a memory of what it has witnessed. I take a step toward her but she turns away. I am released into freefall.

Then the vision comes unbidden. Why does the mind allow intrusion against our will? I saw her falling. I saw my mother falling. She did not fall in parts. She fell in her entirety through a powder of the dove-grey dust of shattered masonry. The white-grey stone leg of the statue of a tall young man fell with her. The subtle difference in the shades of white and grey that day delineated contours as sharply as crimson on a black background. The stone boy had stood sentinel in the long colonnade that connected the drawing room to the conservatory. He had been a reliable companion in the childhood games I had played with my brother. He had been just. He had never taken sides. The conservatory, I remember, did not disintegrate that day. Such anomalies are more common in the aftermath of bombing than one might imagine. My mother had just left the drawing room and was, in her last minutes, close to her stone companion who, heroically, fell with her, his leg the first dismembering, then the second, his arm. It broke off in an arc and for a moment it seemed as though he threw it towards her —as if to say, “Take it, take it! Cling to this, this part of me that I offer to you.” Then the falling, fast. The vision dies. And I am here, again, in this place. At an Irish funeral, my first Irish funeral.

Bishop Fullerton now approaches Mrs. O’Hara. He talks to her. Rather, he talks at her. She simply looks at him. Does he also feel trapped? He steps back from her slightly. I move forwards. Each of us is wrong. She turns away and toward her husband. It’s time to go home. Tom O’Hara guides her away. Mourners separate to make a path for them. Priest and bishop stand aside for them. Their grief takes precedence over the normal hierarchical structure of this community. Murmuring quietly, a procession follows them. Some scatter to left or right to stand by other graves. Eamonn, the bishop’s driver, who takes him to and from my house for our chess evenings, approaches me. Would I like to go with the bishop to the O’Haras’ house? I am uncertain whether this invitation comes from Bishop Fullerton or from the O’Hara family. I decline. I will walk home. Though hours remain this day is over.

TWO

It is not true that I discourage visitors from Lake House. It is, however, true that I do not issue invitations. I exclude from this assessment my monthly chess game with Robert Carter and, on separate evenings, with Bishop Fullerton. Since this is a surprisingly formal society I am untroubled by any intrusion by townspeople, other than those who make the three-mile journey for the not necessarily companionable purpose of earning their living.

There exists between myself and Bridget, my non-resident housekeeper, respect, tolerance, and on her part determination that Irish charm will eventually wear me down and I will, “like all strangers who come here, Mr. Middlehoff, fall in love with the place.” Her use of my name is in its own way an act of intimacy, since I am aware that in the town they simply call me “the German.” As a statement of exclusion this is as accurate as it is definitive. It is one I welcome. I believe I carry with me what every German carries with them, an aura, an emanation. I am German. You know me. I regard myself as under an obligation in this matter. “That this is done shall stand for ever more.” And a day. I am mindful of my responsibility as a member of a cursed tribe. In Ireland there is of course no “te absolvo.” There is, however, little interest in a story of evil that the Irish do not fully believe possible. For had they known the truth, some slight readjustment to their view of their own modern history might have been necessary. The moral demands, even of peripheral images, might have blurred the purity of their ancient vision. However, I continue to appreciate a certain discretion concerning the history of my country that I had not found elsewhere in my exile.

Though I remain sensible to my inclusion almost two months ago in the congregation of mourners at the funeral of the boy, I do not seek, nor have I been offered, further integration. Robert Carter, whose medical attendance on the day of the accident had been in a sense accidental, has also retreated to the comparatively isolated position of Protestant doctor in an Irish town. My friendship with him, a former Major in the Medical Corps of the British Army, is no doubt mysterious to them. Perhaps they are convinced that it is based solely on a passion for the game of chess, a game for which their temperament renders them wholly unsuited. As I wonder whether my father would agree with this judgement I hear the sound of a car on gravel and, looking from my study window, see Tom O’Hara emerge from his battered Morris Minor like a man who had been trapped too long in a small cupboard and must now carefully test the limbs that had been forced into abnormal contortions. He looks around and then, it seems, straight at me as I stand by the window. I have no alternative but to leave my study and proceed down the long parquet-floored hall towards the dark oak door that separates me from this uninvited guest. I open my heavy door, slowly.

“Good morning Mr. Middlehoff. I’ve come about the gate.”

“Good morning Mr. O’Hara.”

“Good morning Mr. Middlehoff,” he says again. And again, “I’ve come about the gate.”

The note is abrupt, even peremptory. How am I to respond? This man, whose rather leonine head and large body speak to a slower, calmer nature, is now in a place I recognise and I know the price the terrain exacts. Courtesy, absolute courtesy is now required. It is a balm and today I apply it for my own protection as well as his.

“Which gate, Mr. O’Hara? Which gate? I’m sorry, Mr. O’Hara, but I do not know to what you refer.”

“Didn’t your estate manager, Tim, mention it?”

“No.”

“I asked him to. You’re sure he didn’t mention it?”

“I am sure.”

“Well then I’m sorry. I wouldn’t be here otherwise.”

“No?”

“Do you think I would just turn up at a stranger’s house, Mr. Middlehoff? Just turn up here and ask him for a gate? Is that what you think of us? Is that the kind of people you think we are?”

“I’m sorry, Mr. O’Hara. This a surprising visit and a most surprising request. As for Tim, he is spending a week in Wexford.”

“In Wexford?”

“Yes.”

“Must be the sister then.”

“Yes.”

“Well, well! The gate. The one with the helmet on the top. You know the one: it marks the end of Lake Lane. You brought it here. Took down Edmund Pennington’s old wooden gate.”

“I know the gate, Mr. O’Hara. It marks the perimeter of my land. So indeed I know the gate.”

“Of course you do. It’s yours! Well, I want to buy it from you.”

“You wish to purchase my gate from me? Why?”

“My son, the lad, admired it. Saw it all the time when he waited in the club rowing boat for the island swimmers to be ready. Gazed at it, told me he made up stories about it. Said it was a warrior’s gate because of the carved helmet at the top. He was at that age. Warriors, heroes, you know.”

And I remember my last conversation with the boy.

“I know what you mean and may I again, Mr. O’Hara, express my deepest sympathy to you and your family.”

“Thank you. Thank you. I’m aware it’s a very strange request.”

“It is, Mr. O’Hara.”

“I’ve got it in my head no other gate will do.”

“That is something that often happens. Will you please come in, Mr. O’Hara? Coffee, perhaps?”

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“[A] compelling look at family and memory, despair and redemption. . . . Passionate and heart-felt.” —The Wall Street Journal

“A quiet masterpiece. . . . It is hard not to go hurtling through this book, with its controlled yet vast embrace of all that is terrifying about living.” —New York Post

“Sophisticated. . . . Hart shows how love of family and love of country can feed from each other.” —The New York Times Book Review

“An ambitious and poetic weaving of a long-ago family tragedy into the tragic history, and histories, of our time. Josephine Hart has come home in triumph.” —John Banville

“In this compelling and remarkable book, Hart has written a moving lament for exile. . . . A tour de force. . . . There are echoes of Beckett and Joyce in Hart’s writing.” —The Times Literary Supplement (London)

“Deeply moving. . . . [The Truth About Love] packs a punch far beyond its size. . . . An uncompromising tale that explores grief, redemption, and misery.” —Irish Independent

“A bleak tale, beautifully told, about the burden we must all, as human beings, survive.” —The Times (London)

“Hart’s dialogue is extraordinary, blending poetry and naturalism like the great Irish playwrights.” —The Independent (London)

“A brave novel. . . . Hart’s [characters] live beyond the confines of even her fiery and elegant prose.” —The Guardian (London)

“[The Truth About Love] embraces themes of heart, soul, pride and shame of country, guilt and memory, emphasizing that the past will not be ignored. . . . Its universal themes will resonate with readers, underscoring that losses are unavoidable for those who love, and enduring is not easy, but that is part of living.” —Las Vegas Review-Journal

“A genuine, deeply felt story of love and loss.” —Daily Mail

“A quiet masterpiece. . . . It is hard not to go hurtling through this book, with its controlled yet vast embrace of all that is terrifying about living.” —New York Post

“Sophisticated. . . . Hart shows how love of family and love of country can feed from each other.” —The New York Times Book Review

“An ambitious and poetic weaving of a long-ago family tragedy into the tragic history, and histories, of our time. Josephine Hart has come home in triumph.” —John Banville

“In this compelling and remarkable book, Hart has written a moving lament for exile. . . . A tour de force. . . . There are echoes of Beckett and Joyce in Hart’s writing.” —The Times Literary Supplement (London)

“Deeply moving. . . . [The Truth About Love] packs a punch far beyond its size. . . . An uncompromising tale that explores grief, redemption, and misery.” —Irish Independent

“A bleak tale, beautifully told, about the burden we must all, as human beings, survive.” —The Times (London)

“Hart’s dialogue is extraordinary, blending poetry and naturalism like the great Irish playwrights.” —The Independent (London)

“A brave novel. . . . Hart’s [characters] live beyond the confines of even her fiery and elegant prose.” —The Guardian (London)

“[The Truth About Love] embraces themes of heart, soul, pride and shame of country, guilt and memory, emphasizing that the past will not be ignored. . . . Its universal themes will resonate with readers, underscoring that losses are unavoidable for those who love, and enduring is not easy, but that is part of living.” —Las Vegas Review-Journal

“A genuine, deeply felt story of love and loss.” —Daily Mail