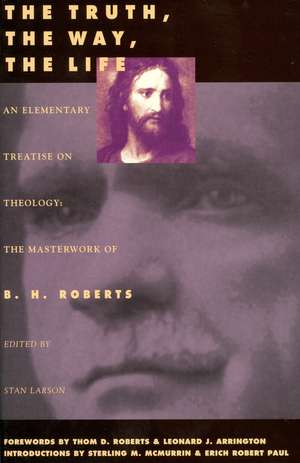

The Truth, The Way, The Life: An Elementary Treaties on Theology

Autor B. H. Robertsen Limba Engleză Paperback – 15 mar 1995 – vârsta ani

Less than ten years before his death in 1933, B. H. Roberts, one of the most influential Mormon writers of the twentieth century, began work on “the most important book that I have yet contributed to the [LDS] Church.” A prolific and respected Mormon apologist, Roberts wanted to consolidate his theological thought into a unified whole and to reconcile science with scripture.

His final manuscript, “The Truth, the Way, the Life,” synthesized doctrine into three sections: the truth about the world and revelation, the way of salvation, and Jesus’ life in shaping Christian character. He submitted his completed work to the LDS First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve, which, after a series of heated meetings, rejected it. Roberts’s views on evolution, the age of the earth, the pre-earth existence, and the eternal progression of God were deemed too controversial, so his “masterwork” went unpublished. With the support of the Roberts family, editor Stan Larson has corrected this sixty-year omission from the corpus of Mormon theology.

According to Leonard J. Arrington, former LDS Church Historian, “B. H. Roberts considered ‘The Truth, The Way, The Life’ to be the most important work he had written. While people may differ with him on that judgement, this ambitious treatise . . . shows a great mind grappling with great issues.”

According to Leonard J. Arrington, former LDS Church Historian, “B. H. Roberts considered ‘The Truth, The Way, The Life’ to be the most important work he had written. While people may differ with him on that judgement, this ambitious treatise . . . shows a great mind grappling with great issues.”

Preț: 178.46 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 268

Preț estimativ în valută:

34.18€ • 35.21$ • 28.63£

34.18€ • 35.21$ • 28.63£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781560850779

ISBN-10: 1560850779

Pagini: 800

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 48 mm

Greutate: 1.25 kg

Ediția:1

Editura: SIGNATURE BOOKS INC

Colecția Signature Books

ISBN-10: 1560850779

Pagini: 800

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 48 mm

Greutate: 1.25 kg

Ediția:1

Editura: SIGNATURE BOOKS INC

Colecția Signature Books

Notă biografică

Stan Larson is the curator for the Utah History, Philosophy, and Religion Archives at the Marriott Library, University of Utah. He is the author of Quest for the Gold Plates; co-author of Unitarianism in Utah; and editor of A Ministry of Meetings: The Apostolic Diaries of Rudger Clawson, Prisoner for Polygamy: The Memoirs and Letters of Rudger Clawson, and Working the Divine Miracle: The Life of Apostle Henry D. Moyle“. Through his own imprint, Freethinker Press, he has edited and published Ray R. Channing’s My Continuing Quest and Marvin and Julia Bertoch’s Modern Echoes from Ancient Hills.

Leonard J. Arrington was the LDS Church Historian and Lemuel H. Redd Professor of Western History at Brigham Young University. He wrote the award-winning Brigham Young: American Moses and the classic Great Basin Kingdom: An Economic History of the Latter-day Saints, and co-authored such works as The Mormon Experience: A History of the Latter-day Saints, Rescue of the 1856 Handcart Companies, and Saints Without Halos: The Human Side of Mormon History. He contributed to Faithful History: Essays on Writing Mormon History, The New Mormon History: Revisionist Essays on the Past, and Personal Voices: A Celebration of Dialogue. Leonard died in 1999.

Sterling M. McMurrin was Academic Vice President and dean of the graduate school at the University of Utah, a Visiting Scholar at Columbia University and the Union Theological Seminary, and a Ford Fellow in philosophy at Princeton. In addition to being U.S. Commissioner of Education (see above), he served as US Envoy to Iran. He was the author of Education and Freedom; Religion, Reason and Truth; and co-author of Contemporary Philosophy; A History of Philosophy; Matters of Conscience;and Toward Understanding the New Testament. He contributed to The Autobiography of B. H. Roberts and Memories and Reflections.

Thom D. Roberts is a lawyer with the Utah State Attorney General’s Office and a great-grandson of Brigham H. Roberts.

Erich Robert Paul was a professor at Dickson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, until his death in 1994. He authored The Milky Way Galaxy and Statistical Cosmology, 1890-1924 and Science, Religion, and Mormon Cosmology.

Thom D. Roberts is a lawyer with the Utah State Attorney General’s Office and a great-grandson of Brigham H. Roberts.

Erich Robert Paul was a professor at Dickson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, until his death in 1994. He authored The Milky Way Galaxy and Statistical Cosmology, 1890-1924 and Science, Religion, and Mormon Cosmology.

Extras

Editor’s Introduction

B. H. Roberts is best known for his publications on LDS history, such as his six-volume Comprehensive History of the Church and his editing of the seven-volume History of the Church. However, he also wrote significant articles and books discussing and defending Mormon doctrine. Roberts wanted to summarize and consolidate all his theological writings into a unified whole; his desire was also to reconcile the scientific knowledge of his day with the scriptures.

Assessments of his completed manuscript of “The Truth, The Way, The Life” (hereafter TWL) are generally positive. Davis Bitton, former assistant LDS church historian, said that TWL “is the single most ambitious and in some ways the most important theological treatise ever written by a Latter-day Saint.[It] can be appreciated as one of the finest productions of a Mormon pen.”1 Erich Robert Paul, a Mormon historian of science, wrote that Roberts’s project “blended a lifetime of views on religion, philosophy, Mormonism, and science into a sort of systematic theology.”2 Truman G. Madsen, one of Roberts’s biographers, said that TWL is “a kind of historical workbook of science and Mormon theology, showing one mind grappling, after solid homework in world thought, with a driving concern to ‘pull things together.’”3 Richard Sherlock, a Mormon philosopher, wrote that Roberts “undertook nothing less than a comprehensive, coherent account of the whole cosmic context of human existence—from the intelligence of God, through the organization of the universe, the creation of man and the development of life on earth, to the role of Christ.”4 And finally LDS apostle George Albert Smith told a colleague that TWL “will be the most comprehensive treatise of the Gospel that has yet been published.”5

The central theme throughout TWL is the life and mission of Jesus the Christ, and it was for this reason that Roberts chose to title the work based on Jesus’ declaration: “I am the way, the truth, and the life: no man cometh unto the Father, but by me” (John 14:6). Roberts conceived of using this scripture as the title while listening to the Mormon hymn which contains the line “O Thou by Whom We Come to God, the Life, the Truth, the Way!”6 Even so, Roberts chose not to follow the exact order and placed truth in first position. TWL summarized and synthesized the distinctive doctrines of Mormonism into three sections: (1) the truth about the world and the importance of revelation, (2) the way to salvation and eternal life for humanity, and (3) the life of Christ and the Christian character.

Within TWL there is a dated reference to the time period when Roberts was writing it. In chapter 46, entitled “Departure from ‘The Way,’” Roberts discussed the apostasy from original Christianity and in the footnote to his own writings on the topic points out that Outlines of Ecclesiastical History “is now (1924) in its fourth edition.” This was during Roberts’s five-year presidency of the Eastern States Mission. The wording was later rephrased with the manuscript stating that this volume “is in its fourth edition (1924).” This provides a terminus of no later than 1927—at least for this particular section of TWL—since a fifth edition of Outlines of Ecclesiastical History appeared in late 1927.

During his tenure as president of the Eastern States Mission, Roberts did some sporadic work on the TWL. Though he was released in April 1927, he took a six-month vacation (with the approval of church president Heber J. Grant) to stay in New York City and dictate a draft of TWL to his former mission secretary, Elsie Cook, who observed in Roberts a “new resolve and concentration.”7 Evidently, much of TWL was dictated during this period.

When Roberts returned to Salt Lake City in October 1927, he continued revising and rewriting the manuscript throughout the next year. In September 1928 Roberts submitted the manuscript of TWL to the Council of Twelve Apostles for approval to publish it as a course of study for the Seventies, and perhaps for all the Melchizedek priesthood of the church.8 Having already checked with the Deseret News Press, Roberts figured that the book could be printed and ready to distribute by mid-November 1928 and he hoped “to incorporate within its pages a full harvest of all that I have thought, and felt, and written through the nearly fifty years of my ministry, that is, on the theme of the title.”9

At the time Roberts submitted TWL to the Twelve in September 1928 there were only 53 chapters in the manuscript. Later he added chapter 54 on the ethic of the last dispensation and many new section headings within the chapters. He also assembled as an appendix to the manuscript a one-page analysis of each chapter, which summarized the headings in the text with an indication of the associated scriptural references. Then in 1929 he wrote chapter 55 on eternal marriage (based on an article published the previous year),10 inserted a paragraph (filling one typewritten page) in chapter 47 on the same subject, and later added to the end of chapter 55 a seven-page explanation of Mormon polygamy. Finally, he distributed the appendix containing all the chapter analysis to the beginning of the respective chapters.

Roberts continued to revise the text and add material to the TWL after it was submitted to the Twelve for approval in September 1928. Roberts added to chapter 4 a page from an article published in September 1930 concerning the discovery of the planet Pluto, which was discovered earlier that year, though it had been predicted in 1905 due to certain irregularities in the motion of Uranus and Neptune.11 At about the same time he updated the statement in chapter 10 concerning the number of planets in our solar system from “eight” to “nine.” In conjunction with Roberts’s presentation to the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles in January 1931, he deleted two sections (“A Catholic Comment” and “The Author’s Comment”) in chapter 31 of TWL—these have accordingly been relegated to an editorial footnote.

The final arrangement of the TWL chapters resembles the five-volume series known as The Seventy’s Course in Theology, with an initial analysis summarizing the major topics and a list of scriptural and other references.

The Controversy

On 3 October 1928 Rudger Clawson, president of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, named George Albert Smith, David O. McKay, Joseph Fielding Smith, Stephen L. Richards, and Melvin J. Ballard as a reading committee to determine if Roberts’s manuscript was suitable as a church study manual.12 The committee met often to read and discuss the manuscript of TWL. In mid-January 1929 Joseph Fielding Smith noted in his diary that the reading committee “met with some difficulties in theories advanced by the author.” In a meeting with Roberts on 26 March 1929 the committee discussed the parts they found objectionable, “trying to agree on some points of difference.”13 Roberts realized the possibility that his manuscript might never be published, but he refused to “change it [even] if it has to sleep.”14 In September 1929 Roberts wrote to a former missionary that he expected that as soon as TWL was published it “would ‘catch like wildfire’ among the youth” of the church.15

In October 1929 George Albert Smith, chair of the reading committee, submitted a report of the committee’s conclusions to Rudger Clawson.16 First, he offered praise that the manuscript “is very worthy treating subjects dealing with the mission of Jesus Christ and gospel principles, which it would be well for all members of the Church to understand.” Then he stated that committee members found “some objectionable doctrines advanced, which are of a speculative nature and appear to be out of harmony with the revelations of the Lord and the fundamental teachings of the Church,” attaching a list of specific items in the chapters that needed revision.17

Early in May 1930 the review committee submitted another report about Roberts’s manuscript. The committee stated their concern about the inevitable importance placed by church members on books written by general authorities, especially when the church is the publisher:

It is the duty of the general authorities of the Church to safeguard and protect the membership of the Church from the introduction of controversial subjects and false doctrines, which tend to create factions and otherwise disturb the faith of the Latter-day Saints. There is so much of vital importance revealed and which we can present with clear and convincing presentation and which the world does not possess, that we, the committee, see no reason for the introduction of questions which are speculative, to say the least. More especially so when such teachings appear to be in conflict with the revelations of the Lord.18

The committee’s second report was re-written. Then on 15 May 1930 the Council of Twelve Apostles as a body wrote a letter to Heber J. Grant and his counselors, noting that “Roberts declined to make the changes or modifications suggested by the Twelve.”19 Accompanying this letter was a list of “Doctrinal Points Questioned by the Committee.” This final list omitted seven problems that had been included in the initial committee report seven months earlier. One of these is enlightening, since the committee had questioned “the superiority of the Prophet [Joseph Smith]‘s definition” of truth.20 Roberts had quoted Smith’s 1833 statement that “truth is knowledge of things as they are, and as they were, and as they are to come,” and added that this explanation “ought to be the completest definition of truth extant among men.”21 Later the committee decided not to oppose a revelation of Joseph Smith, which had been incorporated into LDS scripture as D&C 93:24. Accordingly, this objection to TWL was dropped.

The official list of doctrinal problems in TWL given in the May 1930 report of the twelve apostles reiterated the rest of the October 1929 objections but added a narrative explanation to most of them. These objections provide a barometer, showing the areas considered sensitive at the time. A representative sampling (from the serious to the trivial) can be covered in the following seven questions22:

1. Did pre-Adamite races of human beings exist on this earth before Adam and Eve? This is the most controversial idea in TWL. Apostle Orson Hyde in a general conference talk in October 1854 said: “The world was peopled before the days of Adam.When God said, Go forth and replenish the earth, it was to replenish the inhabitants of the human species, and make it as it was before.”23 Roberts argued that church president Brigham Young approved of Hyde’s doctrine (although Young’s remarks probably endorsed Hyde’s sermon on marriage in general, not Hyde’s notion of pre-Adamites).24 The methodology pursued by Roberts was to accept “the truths of science no less than the truths of revelation.”25 In an effort to reconcile the biblical account about Adam with the paleontological record about the age of humankind, Roberts postulated that there were pre-Adamite races on the earth long before Adam.26 The review committee objected to his hypothesis, saying that “it is speculation leading to endless controversy.” They also admitted “that one of the brethren (Orson Hyde) in an early day advocated this teaching; however, we feel that the brethren of the general authorities cannot be too careful, and should not present as doctrine that which is not sustained in the standards of the Church.” Roberts’s handwritten responses were that he had “not so presented” this teaching and that Orson Hyde’s teaching “was approved also by Pres. Young.”

2. Was life on the earth destroyed and made desolate before the time of Adam? Roberts pointed out the two creation accounts in the first two chapters of Genesis. The first, which begins with chaotic matter, discusses a natural development, and culminates in the creation of man, is found in Genesis 1:1-2:3a. The second, which begins with the creation of man, the placing of him in the garden, and the creation of animal life, birds, and fish, is found in Genesis 2:3b-25. In the second creation account Roberts offered the interpretation that “man seems to get his earth-heritage in a barren state, as if some besom [broom] of destruction had swept the earth; and it must be newly fitted up as a proper abode for him from desert barrenness to a fruitful habitat.”27 Roberts speculated that “previous to the advent of Adam upon the earth, some destructive cataclysm, a universal glacial period, or an excessive heat period left the earth empty and desolate.”28 The pre-Adamites and other life on earth were destroyed due to this overwhelming cataclysm before the time of Adam, leaving the earth in a “desolate” state.29 The committee responded that “the place of man in the order of creation is questioned.”

3. Did Adam come to this earth as a translated being? Roberts, using Brigham Young’s controversial Adam-God discourse of 9 April 1852, asserted that Adam came to this earth from some other world. Roberts, however, did not accept Young’s view that Adam was God, that he had “a celestial body” when he came to the earth, and that he became mortal through eating the forbidden fruit.30 Roberts’s position was that Adam was a “translated” being.31 The committee said “the doctrine that Adam came here a ‘translated’ being from some other world is not accepted as a doctrine of the Church.” They also added that the fall of Adam “brought death into the world.”

4. How is an intelligence different from a begotten spirit? Actually, Joseph Smith rased the terms “intelligence,” “spirit,” “soul,” and “mind” synonymously. In the early Nauvoo, Illinois, period he taught that “the Spirit of Man is not a created being; it existed from Eternity & will exist to eternity,”32 “I believe that the soul is eternal; and had no beginning; it can have no end,”33 and “the spirit or the intelligence of men are self-Existent principles before the foundation [of] this Earth.”34 On 7 April 1844 during the King Follett discourse, which some consider to be his finest doctrinal sermon, Smith said: “The soul—the immortal spirit—the mind of man. Where did it come from? All doctors of divinity say that God created it in the beginning, but it is not so. The very idea lessens the character of man, in my estimation.Man existed in spirit; the mind of man—the intelligent part—is as immortal as, and is coequal with, God Himself.I take my ring from my finger and liken it unto the mind of man—the immortal spirit—because it has no beginning or end.”35 Since in Smith’s view the human spirit existed from eternity, there was no need to describe a point when a spiritual birth or creation occurred.

One of the current distinctive doctrines of Mormonism is the belief that all human spirits are the offspring of God through a spiritual birth process. Consequently, a philosophical dilemma exists for Mormon theologians. One scholar explains that “harmonizing Joseph Smith’s teaching that spirits have no beginning with the contemporary Mormon belief that spirits come into existence through a spirit birth” has produced two solutions.36 The first explains that uncreated intelligence is combined with a spiritual body begotten from heavenly parents to produce a conscious spirit person. In this way the human spirit is eternal in the sense that the elements are eternal. The other explanation is that the conscious mind or intelligence always existed, but the next major stage in progress is the union of the individual intelligence with a spirit body, which is created through procreation. This difference of interpretation still persists today.37

Roberts argued that “man is spirit (intelligence within a spirit body) and this spirit is native to the ‘light of truth.’”38 The committee objected that his use of the terms intelligence and spirit is confusing, saying that an intelligence was an unorganized, unbegotten, uncreated “eternal entity” and that only after intelligences become begotten spirits could they rebel. Roberts wrote in response that this objection was “of no substance or importance” and that there was a “misapprehension here,” since intelligence was “that which perceives truth.” However, in response to (and in accordance with) the committee’s suggestion Roberts revised his text of TWL by adding the three words in italics: “Some intelligences as spirits will rebel against the order of things in the universe as did Lucifer and his following.”39 Accordingly, Roberts was not stubbornly defending every word of TWL, as is sometimes stated.

5. When does the pre-existent spirit enter the body? Answers in Mormon doctrinal discussion have been varied—from conception, to quickening, to birth.40 Roberts discussed the doctrine of “infusionism” as propounded by Origen in the third century, which states that the preexistent human soul is infused into the physical body at conception or at birth.41 Since there exists no official LDS statement on this issue, the committee “questioned the advisability of stating any given time when the spirit unites with the body.” Actually, Roberts did not here state whether this union of body and spirit occurs at conception or at birth, but five chapters later he expresses an opinion in favor of birth based on the pre-existent Christ’s statement to Nephi that the next day he would be born (3 Ne. 1:12-13).

6. Does God’s omniscience mean that he increases in knowledge? In the 1850s Brigham Young and Orson Pratt argued over this question. Pratt had written in 1853 that “the Father and the Son do not progress in knowledge and wisdom, because they already know all things past, present, and to come.”42 Young countered in 1854 that “there never will be a time to all Eternity when all the Gods of Eternity will scease [sic] advancing in power knowledge experience & Glory.”43 In conjunction with the principle of eternal progression, Roberts asserted that God’s omniscience is limited, since he still progresses in knowledge. Roberts offered a revised definition of omniscience, saying that it is not the case “that God is Omniscient up to the point that further progress in knowledge is impossible to him; but that all the knowledge that is, all that exists, God knows; all that shall be he will know.”44 The committee objected that this doctrine was “limiting God” and would “cause needless controversy” among church members. The committee added that God’s “progress is because of his knowledge and that he is the author of law.” Roberts’s handwritten response was “Meaningless.”

7. Does the Church of Christ change? Lastly, Roberts described the organized structure of the LDS church in the early 1830s as the “humble first forms of the Church.”45 The committee questioned this phraseology since “the thought may be conveyed that the forms of the Church had been changed, rather than developed.” Roberts wrote in the margin that this objection was “Nonsense!”46

On 22 May 1930 Roberts told Heber J. Grant that he was “determined not to make any change” in the manuscript to TWL Grant felt “very sorry to think that Brother Roberts is determined to put in the book some things that I think are problematical and cannot be demonstrated.”47

A month before the committee’s report was submitted, Joseph Fielding Smith, a member of the reading committee, publicly criticized Roberts’s ideas in an April 1930 discourse, even though he did not mention Roberts by name. Smith proclaimed:

Even in the Church there are a scattered few who are now advocating and contending that this earth was peopled with a race—perhaps many races—long before the days of Adam. These men desire, of course, to square the teachings in the Bible with the teachings of modern science and philosophy in regard to the age of the earth and life upon it. If you hear any one talking this way, you may answer them by saying that the doctrine of “pre-Adamites” is not a doctrine of the Church, and is not advocated nor countenanced in the Church. There is no warrant in the scripture, not an authentic word, to sustain it.There was no death in the earth before the fall of Adam. I do not care what the scientists say in regard to dinosaurs and other creatures upon the earth millions of years ago that lived and died and fought and struggled for existence. All life in the sea, the air, on the earth, was without death. Animals were not dying. Things were not changing as we find them changing in this mortal existence, for mortality had not come.48

Smith thus emphatically denied that death existed before the fall of Adam and stated that the existence of “pre-Adamites” was not church doctrine.

Roberts, furious over the publication of Smith’s discourse, considered it “a veiled attack” on his TWL.49 On 15 December 1930 Roberts demanded a chance to present his position to President Heber J. Grant, telling him that:

If Elder Smith is merely putting forth his own opinions I call in question his competency to utter such dogmatism either as a scholar or as an Apostle. I am sure he is not competent to speak in such manner from general learning or special research work on the subject; nor as an Apostle, as in that case he would be in conflict with the plain implication at least of the scriptures, both ancient and modern, and with the teaching of a more experienced and learned and earlier Apostle [Orson Hyde] than himself.50

The apostles were indignant at Roberts’s strong words and wrote to Grant that they regarded Roberts’s language “as very offensive on the part of Elder Roberts, who fails to show the deference due from one brother to another brother of higher rank in the Priesthood.”51 On 30 December 1930 Rudger Clawson asked Roberts for more details on his objections. The next day Roberts basically reiterated to Clawson the 15 December letter.

The apostles agreed to listen to both opponents. In preparation for this meeting Roberts almost quadrupled the size of chapter 31, which discussed the antiquity of humankind on the earth.52 On 7 January 1931 Roberts read to the assembled Quorum of Twelve Apostles his fifty-page paper on the “Antiquity of Man,” which argued for pre-Adamites and documented his objections to the discourse of Joseph Fielding Smith. Roberts accepted the chronology for Adam as about 6,000 to 8,000 years ago; he never questioned the literalness of the story of Adam in the book of Genesis nor did he try to interpret it symbolically. But since he also accepted the scientific dating of the geological record, he was forced to postulate the existence of pre-Adamites, a cataclysm before the advent of Adam, and the Adamic dispensation as a new beginning for the earth. Roberts said:

You Brethren will have observed also perhaps that I have not followed any pin-picking method of argument in dealing with the excerpts from Elder Smith’s discourse presented here, but rather have depended upon great, sweeping, cumulative, and to me overwhelming evidences of man’s ancient existence in the earth.But they [the scriptures] may be reconciled with the facts of death upon the earth in ages previous to Adam—as the discoveries of men undoubtedly prove—if Adam’s advent is understood as describing the introduction of a special dispensation on the earth to accomplish some particular purpose of God in the development of man such as bringing him into special spiritual relationship with him, and men into special relationship with one another.53

One week later Heber J. Grant and Anthony W. Ivins of the First Presidency met with James E. Talmage, who was both an apostle and a geologist, and asked for his opinion concerning the antiquity of humanity. Then on 21 January 1931 Joseph Fielding Smith read his paper to the Twelve, with Roberts in attendance.54 Smith stated that the Devil or Satan is actively “giving revelation and poisoning the minds of men” and then asserted his position that “the doctrine of organic evolution which pervades the modern-day sciences, proclaiming the edict that man has evolved from lower forms of life through the Java skull and last, if not least, the ‘Peking man,’ who lived millions of years ago, is as false as their author who reigns in hell!”

Smith also pointed out that Roberts’s teaching on pre-Adamites “has caused indignation, some resentment, and a great deal of serious concern” among church members.55 However, there was no discussion among the apostles at either meeting concerning the merits of either position. The next day Rudger Clawson reported at the apostles’ regular Thursday council meeting in the temple concerning the presentations by Roberts and Smith, and Smith expressed pride that Clawson’s summary was “favorable to me.”56

After President Grant read the papers by Smith and Roberts, he said: “I feel that sermons such as Brother Joseph [Fielding Smith] preached and criticisms such as Brother Roberts makes of the sermon are the finest kind of things to let alone entirely. I think no good can be accomplished by dealing in mysteries, and that is what I feel in my heart of hearts these brethren are both doing.”57 Roberts expressed his own feelings during this period: “I have been passing through the severest mental and spiritual strain of my life during the past two months—Doctrinal questions before the Twelve and the First Presidency in connection with my book The Truth, The Way, The Life, respecting which there seems to be little prospect of settlement.”58

Quietly James E. Talmage wrote to his son, Sterling Talmage, also a geologist, and asked him to ascertain the reputation of George McCready Price, whose book entitled The New Geology was being used by Joseph Fielding Smith against Roberts. Sterling wrote back that “neither the book nor its author has any standing whatever among American geologists,” and the only school using Price’s book as a geology textbook was the fundamentalist Wheaton College.59 This information was useful to Talmage, who attempted to preserve “ostensible neutrality or official non-cognizance of some thing.”60

Since no discussion had occurred during the two presentations, Roberts asked Grant for a chance to respond to Smith’s presentation. Roberts asserted to Grant that Smith’s views were weaker than “a house of cards,” but that it was due to “such pabulum” uttered by Elder Smith that the publication of TWL was being suspended.61 Two weeks later the First Presidency met with Roberts for two hours to discuss the problem.

The Twelve could not resolve the opposing positions and transferred the problem to the First Presidency for resolution. The First Presidency concluded not to make a decision on this issue, and a seven-page statement, probably written by Anthony W. Ivins, was distributed on 5 April 1931 to all general authorities.62 In this document, which did not favor one side or the other, the First Presidency said:

The statement made by Elder Smith that the existence of pre-Adamites is not a doctrine of the Church is true. It is just as true that the statement: “There were not pre-Adamites upon the earth” is not a doctrine of the Church. Neither side of the controversy has been accepted as a doctrine at all. Both parties make the scripture and the statements of men who have been prominent in the affairs of the Church the basis of their contention; neither has produced definite proof in support of his views.We can see no advantage to be gained by a continuation of the discussion to which reference is here made, but on the contrary are certain that it would lead to confusion, division, and misunderstanding if carried further.63

Two days later the First Presidency reaffirmed in a meeting with general authorities that the church had no position on this controversial matter. George Albert Smith stated that the brethren sustained the First Presidency’s decision that “we know nothing about such a people” as the pre-Adamites.64 Apostle George F. Richards recorded that “the subject of pre-Adamites [was] not to be discussed in public by the brethren,” whether speaking for or against the pre-Adamite theory.65 Apostle James E. Talmage felt that the First Presidency had made a wise decision and added that “this is one of the many things upon which we cannot preach with assurance, and dogmatic assertions on either side are likely to do harm rather than good.”66

Rudger Clawson wrote to the reading committee, asking them to again request Roberts to remove from TWL all references to pre-Adamites and the other matters found objectionable. Suspecting that their efforts might not be fruitful, Clawson also told the committee that they should make clear to Roberts that the church would not publish TWL or use it as a textbook in priesthood quorums unless he complied with this request Clawson dosed by saying that he hoped Roberts would realize that the wisest policy to follow would be to make recommended changes, so that “an excellent work may not go unpublished and be lost to the Church.”67

Roberts was not willing to make the suggested alterations. Later that month wrote that the “addition of scientific evidences added to this chapter was prepared for a special paper for the Twelve” on 7 January 1931, and he wanted this additional material included in chapter 31.68

On 9 August 1931 James E. Talmage delivered a discourse at the Salt Lake tabernacle entitled “The Earth and Man,” which delineated a middle-of-the-road position “between elders Smith and Roberts by denying Elder Smith’s attacks on the scientific method and recognizing the speculative nature of Roberts’s position.”69 In contrast to Smith’s publicly stated view, Talmage clearly declared that life and death occurred before the fall of Adam:

The oldest, that is to say the earliest, rocks thus far identified in land masses reveal the fossilized remains of once living organisms, plant and animal. The coal strata, upon which the world of industry so largely depends, are essentially but highly compressed and chemically changed vegetable substance. The whole series of chalk deposits and many of our deep-sea limestones contain the skeletal remains of animals. These lived and died, age after age, while the earth was yet unfit for human habitation.70

Talmage asserted that the scientific record and the biblical account will eventually coincide, since they are different approaches to the same truth: “The Creator has made record in the rocks for man to decipher; but He has also spoken directly regarding the main stages of progress by which the earth has been brought to be what it is. The accounts can not be fundamentally opposed; one can not contradict the other; though man’s interpretation of either may be seriously at fault.”71 He also discussed the hypothesis of pre-Adamic races but pointed out that there is no settled consensus concerning it:

Geologists and anthropologists say that if the beginning of Adamic history dates back but 6000 years or less, there must have been races of human sort upon earth long before that time—without denying, however, that Adamic history may be correct, if it be regarded solely as the history of the Adamic race. This view postulates, by application of [James D.] Dana’s affirmation already quoted: “that the intervention of a power above Nature” brought about the placing of, let me say, Adam upon earth. It is but fair to say that no reconciliation of these opposing conceptions has been effected to the satisfaction of both parties.72

Initially there was strong opposition by some apostles to having Talmage’s discourse published, since they worried that church members might wonder: “If there was life and death and a race of men before the fall of Adam, then there must have been two Adams and two falls, also two fathers of the human family, all of which would lead to utter confusion.”73 The advice of Apostle John A. Widtsoe, who was presiding over the church’s European Mission, was sought, and he recommended that Talmage’s discourse be published. Later Widtsoe discovered that fellow apostle Joseph Fielding Smith “felt personally betrayed and humiliated by this response.”74 After at least four meetings on this matter the First Presidency “authorized its publication” in November 1931, both in the church section of the Deseret News and as a separate pamphlet.75 Talmage admitted that Joseph Fielding Smith was well aware that “my address was in some important respects opposed to his published remarks.”76 This is confirmed by a copy of Talmage’s pamphlet, upon which Joseph Fielding Smith wrote the words “False doctrine.”77

In March 1932 Roberts gave Talmage one chapter of TWL, which he read and returned three days later.78 From Roberts’s comment that he had added more evidence on the antiquity of humankind, this chapter can be identified as the controversial chapter 31, “An Adamic Dispensation.”

During a discourse delivered at the April 1932 general conference Stephen L. Richards, a member of the TWL reading committee, preached that fanaticism and bigotry among members were “the deadliest enemies of religion in the past” and asked LDS members to have more “sympathy and tolerance” for others. Richards continued:

No man’s standing in the LDS church should be affected by his belief in the beginning of man’s life or the beginning of the universe. He [Richards] held that it is the privilege of members to differ on this and other subjects and still be good Latter-day Saints. He added, however, that no one with a real affection for the church will urge views on these points which will tend to undermine the faith of the young in their religion.79

In March 1933 Roberts wrote in The Improvement Era that “truth, whether revealed of God or discovered by research of man, must be harmonious” and that the LDS church is not bound to the outdated theory of “the limited time of duration for the existence of the world.”80 Near the end of his life he expressed the desire that members of the church “would carefully and thoroughly examine every [gospel] principle advanced to them and not only intellectually assent to it as a grand system of truth, but also become imbued with its spirit and feel and enjoy its powers.”81

As early as 1929 when the reading committee began objecting to various statements in TWL, Roberts warned them that he might publish the book “on his own responsibility,” without church approval.82 By August 1933 he had decided to follow this course and planned to publish TWL “under his own direction without Church backing” and the only thing standing in his way was raising enough money to finance publication.83 He no longer feared ecclesiastical retribution, which might cause him to lose his position in the First Council of the Seventy or in the church. Roberts died the next month before he was able to raise the funds necessary to publish TWL84 Roberts family members tell the story that the day he died, Joseph Fielding Smith went into Robert’s office and took his manuscripts of TWL.85

Even though neither Joseph Fielding Smith not Roberts obtained church approval to publish their respective views when the matter was decided in April 1931, Smith outlived Roberts and those sympathetic to his position. James E. Talmage had also died in 1933, and by the end of 1952 John A. Widtsoe and Joseph F. Merrill—two others who were both apostles and scientists—died. Then in 1953 Smith began giving public discourses on the origin of humanity, using a literalistic interpretation of scripture and deriding the theories of scientists. He also made minor revisions updating his own book-length manuscript, asked Mormon scientist Melvin Cook to offer suggested improvements,86 and in April 1954 published it as Man: His Origin and Destiny.

In this volume Smith quoted various LDS leaders, but the professionally trained scientists among the apostles (Talmage, Widtsoe, and Merrill) were not even mentioned. Smith stated the following about pre-Adamites, again without mentioning B. H. Roberts: “There is no Redeemer other than Jesus Christ for this earth and since Adam could not have brought death on pre-Adamite life, such life could not obtain the blessings of the resurrection. Yet the Lord has declared that through the atonement all things partaking of the fall will be redeemed. So there were no pre-Adamites.”87

Pointing out that the Piltdown Man was discovered in 1953 to be a forgery, Smith announced with great delight:

The advocates of this pernicious theory [organic evolution] go to the most ridiculous lengths and resort to the most absurd conclusions based on imaginary discoveries and fables. They are possessed with imaginary minds and when the facts fail them, as the facts always do, they can create species and groups and supply missing parts which in their imaginations disappeared millions of years ago.In all of these “finds” the wish has been father to the thought, so overly anxious have these “discoverers” been to find some connecting links between man and the lower animals that would give evidence of a common origin. These “missing links” have not been forthcoming and the plotters have been forced to resort to fraud and deception to bolster up their futile attempts to prove a Satan-inspired cause, the real purpose being to destroy faith in God.88

Duane E. Jeffery, professor of zoology at Brigham Young University, states concerning Man: His Origin and Destiny:

The work marks a milestone. For the first time in Mormon history, and capping a full half-century of publication of Mormon books on science and religion, Mormonism had a book that was openly antagonistic to much of science. The long-standing concern of past Church presidents was quickly realized: the book was hailed by many as an authoritative Church statement that immediately locked Mormonism into direct confrontation with science, and sparked a wave of religious fundamentalism that shows little sign of abatement.89

Henry Eyring, dean of the University of Utah graduate school and an eminent LDS scientist, responded to Smith’s book by saying that “the consensus of opinion among the foremost earth scientists places the beginning of life on this earth back at about one billion years and the earth itself as two or three times that old.”90

In late June 1954 Joseph Fielding Smith, quoting numerous times from his recently-published book, told Mormon seminary and institute of religion teachers at Brigham Young University that “the hypothesis of organic evolution is one of the most cunningly devised among the fables” made by men.91 A little over a week later J. Reuben Clark, Jr., second counselor in the First Presidency, delivered to the same audience his speech on when the teachings of church leaders are scripture, explaining that “when any man, except the President of the Church, undertakes to proclaim one unsettled doctrine, as among two or more doctrines in dispute, as the settled doctrine of the Church, we may know that he is not ‘moved upon by the Holy Ghost,’ unless he is acting under the authority of the President.”92 Clark’s speech amounts to a response to, and rebuke of, Smith’s remarks nine days earlier.

Joseph Fielding Smith died in July 1972 and his Man: His Origin and Destiny was reprinted for the last time the next year; it had gone through seven printings and more than 31,000 copies were published.

After Harold B. Lee succeeded Smith as church president, there were renewed negotiations to publish the TWL. Truman G. Madsen, a professor of philosophy and religion at BYU, during a lecture to his school’s philosophy colloquium in October 1973 announced that President Lee wanted TWL to be published and that it would be published in 1974.93 Lee’s unexpected death in December 1973 scuttled these plans.

In 1973 Duane E. Jeffery wrote an article on organic evolution and was allowed to mention Roberts’s manuscript in a footnote since Madsen had been officially commissioned to write on it.94 The next year Davis Bitton, who as assistant church historian had access to the manuscripts of TWL in LDS Church Archives, wrote a still-unpublished paper on Roberts’s “masterwork.”95 In 1975 Madsen analyzed the role of Jesus Christ in TWL and included short quotations from numerous chapters.96 He then devoted a chapter on TWL in his 1980 biography of B. H. Roberts.97 That same year Richard Sherlock published an article surveying the controversy between Roberts and Smith on evolution and pre-Adamites.98

By mid-1981 photocopies of a group of TWL chapters—chapters 24-26, 30-32, 37, and the appendage to 55—had begun circulating among LDS researchers. From these newly-surfaced chapters of TWL, chapter 26 was published in The Seventh East Press, an unofficial BYU student newspaper, in December 1981.99 Continuing his interest in TWL, Truman Madsen published an article in 1988 on Roberts’s analysis of the doctrine of the Atonement in the Book of Mormon.100

As of 1985 twenty-three chapters were still missing in the TWL text available outside LDS Archives. This material included places where words were illegible. In addition, entire pages were missing and poor photocopies made it unclear whether Roberts intended the material as part of the text or as a footnote. In spite of these problems Brian H. Stuy in 1984 published the available chapters as “excerpts” from Roberts’s TWL.101

In January 1992 Edwin B. Firmage donated to the University of Utah Marriott Library his personal copy of Roberts’s typed manuscript of TWL. It contains the entire fifty-five chapters.102 Previously the library’s B. H. Roberts Collection was missing the following chapters: 4-5, 11-19, 22-23, 29, 36, 38, 46-48, 50-53; as well as pages 34 of the introduction and pages 13 and 15 of chapter 3. These 330 missing pages amounted to 42 percent of the entire manuscript.

The provenance of the Firmage manuscript of “The Truth, The Way, The Life,” which is used in the present edition, is as follows. Firmage received the manuscript from his maternal grandfather, Hugh B. Brown, in the late 1960s. Brown had admired Roberts, and they often traveled together and spoke from the same pulpit. Brown reminisced that Roberts “became my ideal so far as public speaking was concerned and contributed much to my own knowledge of the gospel and to my own methods of presenting it.”103 In the mid-1960s Brown became concerned that Joseph Fielding Smith, long a fierce rival of Roberts and opponent to publication of the [TWL] manuscript, might destroy this document upon becoming President of the Church.”104 Brown was then first counselor to President David O. McKay and essentially acting president of the church due to the declining health of McKay, who was non compos mentis from mid-1965 until his death in January 1970. Brown, on his own authority as a member of the First Presidency, made a copy of Roberts’s manuscript of TWL and gave it to his grandson, Edwin B. Firmage, with instructions that it be preserved.

When Firmage donated the manuscript of “The Truth, The Way, The Life” to the Marriott Library on 16 January 1992, he stated that he was not claiming copyright to TWL or that he necessarily wanted or did not want TWL to be published.105 After receiving his gift, I informed Firmage that I intended to edit TWL for publication.

Because the LDS church has restricted its B. H. Roberts Collection (Manuscript 1278), Roberts’s papers there cannot be examined. This includes the following three “drafts” of TWL: (a) Draft #1 (hereafter Ms I), an early typed draft with handwritten additions probably done in New York in 1927; (b) Draft #2 (hereafter Ms II), a dean typescript incorporating suggested additions from Ms I, with additional handwritten corrections; and (c) Draft #3 (hereafter Ms III), a carbon copy of the clean typescript of Ms II, with typed additions of the handwritten corrections in Ms II, and further handwritten corrections, as well as material dated from 1929, 1930 and 1931. The manuscript at the Marriott Library is a copy of the most important of the three drafts—Ms III.106

Editorial Approach

My rationale in the present volume has been to provide an accurate and complete text of TWL, using mainly the latest of the three manuscripts. However, to present the final wording intended by Roberts, this edition is necessarily an eclectic text, because unintentional errors in the manuscript have been corrected (with the reading of the manuscript given in the notes). I do not suggest which are Roberts’s stronger points and which are weaker—determining the validity of Roberts’s arguments is reserved for the reader. The following are the major guidelines used in producing this edition.

The underlining in the text of TWL, which is here printed as italics, has been retained. If needed for consistency or better readability, periods, commas, apostrophes, colons, semicolons, quotation marks, question marks, capitals, hyphens, and dashes have been deleted, changed, or silently introduced into the text Spelling errors have been changed. The ampersand (&) has been expanded to “and,” except in the abbreviation “D&C.” Sometimes paragraphing has been modified. The use of asterisks (***) by Roberts to indicate the omission of short or long segments in a quotation has been altered to the current style of using an ellipsis of three periods. There were a few instances where verbs were changed to either a singular or plural form to provide grammatical agreement with the subject, or where nouns used as adjectives have been changed to their adjectival forms. The insertion of sic has been made in a few instances to indicate that the wording is exactly as given.

Words unintentionally repeated in the original and other inadvertent and typographical errors have been silently corrected. Sometimes an internal quotation within a paragraph has been set apart as an indented block quotation, requiring minimal rearrangement of the introductory wording. Unexpectedly, it was often found that what appeared in the typed Ms III to be Roberts’s wording was in fact a verbatim quotation by Roberts from another source—accordingly such sections were indented as block quotations, with the identifying bibliographic reference added. However, Roberts also extensively quotes from his own previously-published articles and books (especially the five volumes of The Seventy’s Course in Theology), but such quotations are not set off as block quotations.

To distinguish clearly between Roberts’s comments and my own, parentheses in the text and square brackets in quotations enclose Roberts’s comments, while carets surround my editorial additions in both the text and quotations. Footnotes by me are placed at the bottom of the page among the footnotes by Roberts, but are enclosed by carets and have “–Ed.” at the end. The printed text represents the latest form intended by Roberts, incorporating his interlinear or marginal revisions.

Sometimes the printed text follows the wording in the quoted source, but the incorrect text of TWL may also be given in the footnote as “Ms III.” In many places where the earlier text of TWL has some interest, the original reading of the third draft of TWL (indicated by the term “Ms III*”) is cited in the careted footnotes, with enough context given to understand what was changed. This provides a glimpse into Roberts’s wording in Ms III before his own correction. The “Ms III*” readings fall into two categories: (1) the original text of Ms III before being revised or (2) the original text of Ms III before being deleted. Sometimes it is helpful to know what words were added to the original text of Ms III—these later additions are indicated in the footnotes by the term “Ms IIIc,” and show how the “Ms III*” developed into the printed text. There are two instances where it is necessary to distinguish not between an original and a revised reading of Ms III, but a revised text made in response to the reading committee report of May 1930. These cases are indicated by “Ms III2″ and are located in chapters 16 and 27. Again it must be emphasized that the manuscript readings of Ms III cited in the careted footnotes are only a selection of the manuscript changes—I have chosen those instances that reveal alterations or refinements in Roberts’s thinking.

There are a few instances of accidental doubling in “Ms III*,” which suggest that Roberts was reading from an earlier draft of TWL and unintentionally his eye skipped up one line, resulting in a doubling of the text (see an example in chapter 34). On the other hand, there are cases of unintentional omission in “Ms III*,” in which his eye skipped down one line (see examples in chapters 9, 11, 12, 33, 35, 43, 44, 49, and 50). This supports the view that TWL went through at least one earlier revision.

There are several indications that Roberts dictated the text to his secretary, Elsie Cook. For example, in chapter 1 during a quotation from John W. Draper the error “science” is typed instead of the correct “sense,” in chapter 8 in a quote from Herbert Spencer the heraldic term “naissant” is typed for the correct”nascent,” in chapter 9 in a quote from John Smart Mill the homophone “reigns” is typed instead of the correct “reins,” in chapter 19 the misspelling “Syphians” is typed for the correct “Scythians,” in chapter 31 “the most Mousterian epoch” is found, probably because Roberts re-pronounced the term “Mousterian” as he was reading from a newspaper account, in chapter 42 quoting Acts 17:27 the error “happily” appears instead of “haply” (meaning, “perchance”), in chapter 46 quoting 2 Timothy 2:18 the spelling “passed” is used for “past,” in chapter 47 error “event” is typed instead of the correct “advent,” in chapter 48 the homophone “adherence” occurs for “adherents,” and likewise, in chapter 51 the homophone “straight” appears for “strait.” All of these sound very much alike.

The concurrence of both types of errors mentioned in the two previous paragraphs indicates that Roberts, reading from an earlier draft of TWL, dictated the text to Cook. Roberts in performing his task occasionally misread the text, and Cook, likewise, at times misheard the dictated text.

In quotations from the scriptures Roberts introduced quotation marks to show the words spoken by an individual. Roberts applied this valuable device sporadically, so I have introduced them more consistently. Likewise, Roberts often capitalized second- and third-person pronouns referring to God, so I have made this a consistent practice. The scriptural references, which Roberts usually gives as footnotes, have been standardized in the form “John 14:6″ and placed in parentheses in the text at the end of the quotation. The standard LDS abbreviations for scriptural references have been used. Minor errors in the references have been silently corrected. If Roberts does not supply the reference for a scriptural quotation, this has been silently added at the end of the quotation within the usual parentheses. The editorial addition of “cf.” within these parentheses and before the scriptural citation indicates that there is some variation in Roberts’s quotation from the King James Version text of the Bible or the other LDS scriptures.

The titles to books, which Roberts generally enclosed by quotation marks or typed in full capitals, have been converted to italics and cited in accordance with modern bibliographic style, often with additional information on full name of author, complete title, publication place, publisher, and year. These improvements have been made in both the footnotes and the “References” column of the synopses at the beginning of each chapter, but not in the text proper of TWL. Two examples of this bibliographic expansion will show how the references have been modified: (1) in chapter 38 Roberts’s reference to “Biblical Theological and Ecclesiastical Enc. by McClintoc & Strong” has been changed to “John M’Clintock and James Strong, ‘Melchizedek,’ Cyclopædia of Biblical,Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature“; and (2) in chapter 42 Roberts’s reference to “Nelsons’s ‘Bible Treasury’” has been corrected to “William Wright, ed., The Illustrated Bible Treasury (New York: Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1896).” If the bibliographic reference is wholly my work, it is enclosed within carets.

The purpose of my footnotes is to cite the variant manuscript readings of Roberts’s Ms III, but the footnotes also update some of the scientific information which has changed in the last six decades, refer to modern scholarly studies on the topic at hand, and point out textual problems in scriptural passages. If readers are interested in seeing Roberts’s manuscript just as he last left it, they can examine it in the Manuscripts Division of the Marriott Library at the University of Utah.

I believe the present publication fulfills B. H. Roberts’s intention by printing the complete text of his Ms III of TWL. Nothing has been left out, including valuable material that Roberts indicated should be added to chapter 31. Truman G. Madsen argues that if Roberts were “alive today, he would likely be anxious that the book remain unpublished. He had, in fact, begun to feel that way before his death.”107 Wesley P. Lloyd’s diary provides contemporary evidence against Madsen’s position, since it records Roberts’s decision in 1933 to publish TWL “without Church backing.”108

The first public announcement of this edition of TWL was given on 6 February 1992 in Salt Lake City at a meeting of the B. H. Roberts Society. The following year in May I sent letters to descendants of B. H. Roberts, asking their permission to publish TWL, since copyright to TWL resides in Roberts’s heirs. Roberts’s descendants from his wife, Sarah Louisa Smith, and his polygamous wife, Celia Dibble, gave their approval. (There were no children by his post-Manifesto wife, Margaret Curtis Shipp.) Two months later I attended the B. H. Roberts Family Reunion, where I explained to descendants the current project. The next month at the annual Sunstone Symposium in Salt Lake City I presented a paper on “The Controversy concerning B. H. Roberts’s Unpublished Manuscript ‘The Truth, The Way, The Life,’” reviewing Roberts’s difficulties with church leaders.

In September 1993 I met with John W. Welch, editor of Brigham Young University Studies which is producing a separate edition of TWL, about collaborating with him. Welch decided against any joint effort. Two months later he announced publicly that the TWL manuscript at the LDS Church Archives had been “newly released.”109 After reading about this “release” of TWL, I went to the archives but found that their Roberts Collection was still closed. I then decided to make a minor request of LDS Archives: to examine just one page of the manuscript. The Firmage manuscript lacks the footnotes at the bottom of the fifth page of chapter 1, since the bottom third of the page had been covered by a handwritten note attached by Roberts himself. In January 1994 LDS Archives granted me permission to examine this one page of Ms III of TWL in their Roberts Collection. I discovered that under the pinned-on note was a previously unknown footnote by Roberts, which is now printed as the twelfth note of chapter 1. The cooperation of LDS Archives in this matter is gratefully acknowledged.

B. H. Roberts would be flattered with the recent revival of interest in his work. Though it is sixty-one years after his death, his long-cherished desire to publish “The Truth, The Way, The Life” is now fulfilled. The volume stands as a testament to his insight into LDS gospel principles and to his courage in stating his opinion in spite of ecclesiastical pressure from higher church authorities.

Footnotes

1. Davis Bitton, “The Truth, The Way, The Life: B. H. Roberts’ Unpublished Masterwork,” 2, typed manuscript, in the David J. Buerger Collection, Ms 622, Bx 10, Fd 7, Manuscripts Division, Marriott library, University of Utah, Salt Lake City (hereafter Buerger).

2. Erich Robert Paul, Science, Religion, and Mormon Cosmology (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1992), 149.

3. Truman G. Madsen, Defender of the Faith: The B. H. Roberts Story (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1980), 345.

4. Richard Sherlock, “‘We Can See No Advantage to a Continuation of the Discussion’: The Roberts/Smith/Talmage Affair,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 13 (Fall 1980): 63; reprinted in Richard Sherlock and Jeffrey E. Keller, “The B. H. Roberts/Joseph Fielding Smith/James E. Talmage Affair,” The Search for Harmony: Essays on Science and Mormonism, eds. Gene A. Sessions and Craig J. Oberg (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1993).

5. George Albert Smith to John A. Widtsoe, 26 Feb. 1929, in George Albert Smith Collection, Manuscript 36, Manuscripts Division, Marriott Library (hereafter Smith).

6. “Prayer Is the Soul’s Sincere Desire,” in Hymns of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1985), no. 145. Truman G. Madsen, “B. H. Roberts: The Book of Mormon and the Atonement,” in The Book of Mormon: First Nephi, The Doctrinal Foundation, eds. Monte S. Nyman and Charles D. Tate, Jr. (Provo, Ut: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1988), 313, found this information when reading the notebooks in Roberts’s now-restricted collection at LDS Archives, Historical Department, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City.

7. Madsen, Defender, 338.

8. Truman G. Madsen, “The Meaning of Christ–The Truth, The Way, The Life: An Analysis of B. H. Roberts’ Unpublished Masterwork,” Brigham Young University Studies 15 (Spring 1975): 259, incorrectly states that it was for an MIA, instead of a priesthood, study course.

9. B. H. Roberts to Rudger Clawson, 17 Sept. 1928, in Ernest Strack Collection, Manuscript A 296, Library, Utah State Historical Society, Salt Lake City (hereafter Strack).

10. B. H. Roberts, “Complete Marriage—Righteousness; Mutilated Marriage—Sin,” Improvement Era 31 (Jan. 1928): 181-92.

11. “The Latest News from Pluto,” The Literary Digest 106 (6 Sept. 1930): 18.

12. Rudger Clawson to Elders George Albert Smith, David O. McKay, Joseph Fielding Smith, Stephen L. Richards, and Melvin J. Ballard, 3 Oct. 1928, in Strack.

13. Joseph Fielding Smith Journal, 15 Jan. and 26 Mar. 1929, according to typescript in Buerger, Bx 10, Fd 8.

14. B. H. Roberts to Heber J. Grant, May 1929, cited by Madsen, Defender, 344.

15. B. H. Roberts to Elizabeth Skolfield Hinckley, 8 Sept. 1929, cited by Madsen, Defender, 341.

16. Madsen, “Meaning,” 259, incorrectly states that David O. McKay chaired the committee.

17. George Albert Smith to Rudger Clawson, 10 Oct. 1929, with a one-page “List of Points on Doctrine in Question by the Committee in Relation to B. H. Robert[s]‘s Ms,” in B. H. Roberts Correspondence, Manuscript SC 1922, Special Collections and Manuscripts, Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah (hereafter Roberts Correspondence at BYU).

18. Report of Committee to the Council of the Twelve, early May 1930, in Buerger, Bx 10, Fd 8. However, Sherlock, “‘We Can See No Advantage to a Continuation of the Discussion,’ 67, 77, reprinted in Shedock and Keller, “The B. H. Roberts/Joseph Fielding Smith/James E. Talmage Affair,” Search for Harmony, 94, 111, cites these same words as being “Council of the Twelve to Heber J. Grant, May 15, 1930, Clawson Papers.” The words of the quotation in the text are not at issue, since both sources agree verbatim, but determining which person or committee said them and when they were written can only be resolved by examining the restricted Clawson and Roberts collections at LDS Church Archives.

19. Council of the Twelve to Heber J. Grant, 15 May 1930, in Buerger, Bx 29, Fd 4.

20. “List of Points on Doctrine in Question by the Committee in Relation to B. H. Robert[s]‘s Ms,” attached to George Albert Smith to Rudger Clawson, 10 Oct 1929, in Roberts Correspondence at BYU.

21. TWL, final draft, known as Ms III, chap. 1, p. 6.

22. The complete texts of the October 1929 “List of Points on Doctrine in Question by the Committee in Relation to B. H. Robert[s]‘s Ms,” the early May 1930 Report of Committee to the Council of the Twelve with a listing of objections, and the final 15 May 1930 “Doctrinal Points Questioned by the Committee Which Read Manuscript of Elder B. H. Roberts, Entitled The Truth, The Way, The Life” are printed in the appendix at the end of this volume.

23. Orson Hyde, “The Marriage Relations,” Journal of Discourses 2 (1855): 79. Hyde interprets the King James Version “replenish” at Genesis 1:28 to mean “re-fill,” but the Hebrew word means to “fill.” Joseph Fielding Smith, Answers to Gospel Questions (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Co., 1957), 1:208, correctly points out the Hebrew meaning.

24. Brigham Young, “Marriage Relations of Bishops and Deacons,” Journal of Discourses 2 (1855): 90.

25. Karl C. Sandberg, “Modes of Belief: David Whitmer, B. H. Roberts, Werner Heisenberg,” Sunstone 12 (Sept. 1988): 13.

26. TWL, Ms III, chap. 31, p. 1.

27. TWL, Ms III, chap. 30, pp. 6-7.

28. TWL, Ms III, chap. 30, p. 7.

29. TWL, Ms III, chap. 32, p. 3.

30. Brigham Young taught this in his 9 April 1852 discourse, entitled “Self-Government—Mysteries—Recreation and Amusements Not in Themselves Sinful—Tithing—Adam, Our Father and Our God,” Journal of Discourses 1 (1854): 46-53. For Young’s controversial Adam-God Doctrine, see David J. Buerger, “The Adam-God Doctrine,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 15 (Spring 1982): 14-58.

31. TWL, Ms III, chap. 32, p. 3.

32. Andrew F. Ehat and Lyndon W. Cook, eds. The Words of Joseph Smith (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1980), 9.

33. Ibid., 33; emphasis in original.

34. Ibid., 68; spelling has been corrected.

35. See the editor’s “The King Follett Discourse: A Newly Amalgamated Text,” Brigham Young University Studies 18 (Winter 1978): 203-204.

36. Van Hale, “The Origin of the Human Spirit in Early Mormon Thought,” in Gary James Bergera, ed., Line upon Line: Essays on Mormon Doctrine (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1989), 122.

37. Dennis J. Packard, “Intelligence,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, ed. Daniel H. Ludlow (New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., 1992), 2:692, says that “some LDS leaders have interpreted this to mean that intelligent beings—called intelligences—existed before and after they were given spirit bodies in the premortal existence. Others have interpreted it to mean that intelligent beings were organized as spirits out of eternal intelligent matter, that they did not exist as individuals before they were organized as spirit beings in the premortal existence.”

38. TWL, Ms III, chap. 27, p. 8.

39. TWL, Ms III, chap. 27, p. 5.

40. Jeffrey E. Keller, “When Does the Spirit Enter the Body?” Sunstone 10 (Mar. 1985): 42-44.

41. TWL, Ms III, chap. 21, p. 9.

42. Gary James Bergera, “The Orson Pratt-Brigham Young Controversies: Conflict within the Quorums, 1853 to 1868,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 13 (Summer 1980): 11, quoting The Seer 1 (Aug. 1853): 117.

43. Scott G. Kenney, ed., Wilford Woodruff’s Journal: 1833-1898 Typescript (Midvale, UT: Signature Books, 1983), 4:288, at 17 Sept 1854. Woodruff also records Young’s 17 February 1856 statement that “the Gods & all intelligent Beings would never scease [sic] to learn except it was the Sons of perdition they would continue to decrease untill [sic] they became dissolved back into their native Element & lost their Identity” (ibid., 402).

44. TWL, Ms III, chap. 42, p. 9.

45. TWL, Ms III, chap. 47, p. 13.

46. “Doctrinal Points Questioned by the Committee Which Read the Manuscript of Elder B. H. Roberts, Entitled The Truth, The Way, The Life,” with marginal handwritten notes by B. H. Roberts, attached to Rudger Clawson to Heber J. Grant, 15 May 1930, in Buerger, Bx 29, Fd 4.

47. Heber J. Grant Diary, 22 May 1930, according to typescript in Buerger, Bx 10, Fd 8.

48. Joseph Fielding Smith, “Faith Leads to a Fullness of Truth and Righteousness,” Utah Genealogical and Historical Magazine 21 (Oct 1930): 147-48, emphasis in original.

49. Wesley P. Lloyd Diary, 7 Aug. 1933, Accession 1338, Manuscripts Division, Marriott Library. Roberts was not the only one disturbed by Smith’s discourse. Geologist Sterling B. Talmage, son of James E. Talmage, wrote (with guidance from his father) a twelve-page open letter to Joseph Fielding Smith, detailing his objections. See the Sterling B. Talmage Collection, Accession 724, Manuscripts Division, Marriott Library (hereafter S. B. Talmage).

50. B. H. Roberts to Heber J. Grant, 15 Dec. 1930, in Scott G. Kenney Collection, Ms 587, Bx 4, Fd 19, Manuscripts Division, Marriott Library. Roberts was referring to Aposde Orson Hyde.

51. Rudger Clawson to Heber J. Grant, 21 Jan. 1931.

52. Originally as submitted in September 1928 chapter 31 contained only nine pages. In an effort to present the most up-to-date information Roberts added twenty-five pages to the text, with the latest newspaper report being mid-December 1930, just three weeks before his presentation to the apostles.

53. B. H. Roberts, presentation to the Quorum of Twelve Apostles, partial typescript, 7 Jan. 1931, in Buerger, Bx 10, Fd 7.

54. The delivery of the paper occurred on 21 January 1931, but the paper itself was finished and dated on 14 January 1931, being written after and in response to Roberts’s presentation on 7 January 1931. Consequently, Richard Sherlock, “A Turbulent Spectrum: Mormon Reactions to the Darwinist Legacy,” Journal of Mormon History 5 (1978): 33 (reprinted in Search for Harmony, 67), being misled by the date at the beginning of the paper, incorrectly assumed that Joseph Fielding Smith presented his paper to the assembled apostles on 14 January. He corrected this error in his more detailed study, “We Can See No Advantage,” 68, 78; reprinted in Sherlock and Keller, “B. H. Roberts…Affair,” in Search for Harmony, 95, 111.

55. Joseph Fielding Smith, Statement to Rudger Clawson, 14 Jan. 1931.

56. Joseph Fielding Smith Journal, 22 Jan. 1931, according to typescript in Buerger, Bx 10, Fd 8.

57. Heber J. Grant Diary, 25 Jan. 1931, in Thomas G. Alexander, “‘To Maintain Harmony’: Adjusting to External and Internal Stress, 1890-1930,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 15 (Winter 1982): 58n37.

58. B. H. Roberts, letter, Jan. 1931, in Madsen, Defender, 344, but the letter should be dated as 3 Mar. 1931.

59. Sterling B. Talmage to James E. Talmage, 9 Feb. 1931, in Ronald L. Numbers, The Creationists (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1992), 311.

60. Sterling B. Talmage to James E. Talmage, 29 June 1931, in S. B. Talmage.

61. B. H. Roberts to Heber J. Grant, 9 Feb. 1931, in 5 Apr. 1931 letter of the First Presidency to General Authorities, in Roberts Correspondence at BYU.

62. Heber J. Grant Diary, 30 Mar. 1931, according to typescript and handwritten note in Buerger, Bx 10, Fd 8.

63. First Presidency to Council of the Twelve, First Council of Seventy, and Presiding Bishopric, 5 Apr. 1931, in Roberts Correspondence at BYU; photocopy of pp. 5-7 in Strack.

64. George Albert Smith Diary, 7 Apr. 1931, in Smith, Bx 67, Bk 10.

65. George F. Richards Diary, 7 Apr. 1931, according to typescript in Strack.

66. James E. Talmage Diary, 7 Apr. 1931, Manuscript 229, Special Collections and Manuscripts, Lee Library, Brigham Young University (hereafter abbreviated to Talmage at BYU).

67. Rudger Clawson to George Albert Smith, 10 Apr. 1931, in Strack.

68. Note of B. H. Roberts, 29 Apr. 1929, inserted before chapter 31 of TWL, in B. H. Roberts Collection, Manuscript 106, Bx 17, Fd 4, Manuscript Division, Marriott Library (hereafter Roberts at UU).

69. Thomas G. Alexander, Mormonism in Transition: A History of the Latter-day Saints, 1890-1930 (Urbana; University of Illinois Press, 1986), 288.

70. James E. Talmage, The Earth and Man: Address Delivered in the Tabernacle, Salt lake City, Utah, Sunday, August 9, 1931 (Salt Lake City: Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1931), 4. Talmage himself had earlier examined the altar of stones at Spring Hill, Missouri, which Joseph Smith identified as Adam’s altar, and found fossilized animals in the stones. Consequently, he conduded that “if those stones be part of the first altar, Adam built it of stones containing corpses, and therefore death must have prevailed in the earth before Adam’s time” (James E. Talmage to Sterling B. Talmage, 21 May 1931, cited by Jeffrey E. Keller, “Discussion Continued: The Sequel to the Roberts/Smith/Talmage Affair,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 15 [Spring 1982]: 83; reprinted in Sherlock and Keller, “The B. H. Roberts/Joseph Fielding Smith/James E. Talmage Affair,” Search for Harmony, 99).

71. Ibid., 5.

72. Ibid., 11, emphasis in original. Evidence now available in the form of letters between Talmage and his geologist son, Sterling B. Talmage, indicate that Apostle Talmage personally believed in the existence of pre-Adamites. See Keller, “Discussion Continued,” 82-83, reprinted in Sherlock and Keller, “B. H. RobertsAffair,” inSearch for Harmony, 93-115.

73. “Report of President Clawson made at the regular weekly meeting of the First Presidency and the Council of the Twelve, October 1,” two-page typescript, dated 20 Nov. 1931, in Roberts Correspondence at BYU.

74. Duane E. Jeffery, “‘We Don’t Know’: A Survey of Mormon Responses to Evolutionary Biology,” in Science and Religion: Toward a More Useful Dialogue, eds. Wilford M. Hess, Raymond T. Matheny, and Donlu D. Thayer (Geneva, IL: Paladin House, 1979), 2:24.

75. Heber J. Grant Diary, 7 Nov. 1931, according to typescript in Strack.

76. James E. Talmage Diary, 21 Nov. 1931, in Talmage at BYU.

77. Thomas G. Truitt identified the handwriting of Joseph Fielding Smith on a copy of The Earth and Man, a photocopy of which is in Strack.

78. B. H. Roberts to James E. Talmage, 18 Mar. 1932, and James E. Talmage to B. H. Roberts, 21 Mar. 1932, in Roberts at UU, Bx 18, Fd 1.

79. “Leader Attacks Dogma, Bigotry as Enemies of Faith,” The Salt Lake Tribune, 10 Apr. 1932, 12. This particular conference talk by Richards has a unique history. That same afternoon the First Presidency and twelve apostles met to discuss “the question of allowing the address delivered by Elder Stephen L Richards” to be published. Richards had also suggested that church members have tolerance towards those who violate the Word of Wisdom, and the Brethren were concerned “whether the effect of this address will be that of leading to the thought that the Church is lowering its standards” (Talmage Diary, 9 Apr. 1932). As a result of Richards’s liberal attitude about the Word of Wisdom and probably also his statement that “some changes in the ordinances, forms, and methods of the church had been made in recent years and that these changes had disturbed some of the members” (quoted from the Tribune), his entire discourse was omitted from the published conference report without comment. This was done in spite of the statement on the title page of One-hundred and Second Annual Conference of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1932) that it contains “a Full Report of All the Discourses.” Forty-seven years later this discourse was finally published in Sunstone; see Stephen L Richards, “Bringing Humanity to the Gospel,” Sunstone 4 (May-June 1979), 43-46.

80. B. H. Roberts, “What College Did to My Religion,” Improvement Era 36 (Mar. 1933): 262.

81. “Foreword,” Discourses of B. H. Roberts [ed. Elsie Cook] (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Co., 1948), [7].

82. George Albert Smith to Rudger Clawson, 10 Oct 1929, in Roberts Correspondence at BYU.

83. Lloyd Diary, 7 Aug. 1933.

84. Unlike President Joseph F. Smith, who died in 1918 with an estate worth $421,783 and a net worth of $415,180, Roberts was not wealthy and at his death his net worth was only $348. See D. Michael Quinn, “The Mormon Hierarchy, 1832-1932: An American Elite,” Ph.D. diss., Yale University, 1976, 141, 149-50, 154.

85. Richard Hollingshaus to Duane E. Jeffery, 23 Nov. 1975, located in Duane E. Jeffery Collection, Accession 1372, Manuscripts Division, Marriott Library (hereafter Jeffery).

86. Melvin A. Cook to Joseph Fielding Smith, 4 Mar. 1954, in Melvin A. Cook Collection, Accession 1148, Manuscripts Division, Marriott Library.

87. Joseph Fielding Smith, Man: His Origin and Destiny (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Co., 1954), 279.

88. Ibid., 157.

89. Duane E. Jeffery, “Seers, Savants and Evolution: The Uncomfortable Interface,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 8 (1973): 65-66; reprinted in Sessions and Oberg, Search for Harmony, 176.

90. Henry Eyring to Adam S. Bennion, 16 Dec. 1954, Henry Eyring Collection, Manuscript 477, Box 22, Fd 5, Manuscripts Division, Marriott Library. Eyring referred to the geological record as “the Creator’s revelations written in the rocks” and went on to say: “The world is filled with radioactive docks …. The radioactive clocks, together with the orderly way many sediments containing fossils are laid down, prove that the earth is billions of years old. In my judgement anyone who denies this orderly deposition of sediments with their built in radioactive docks places himself in a scientifically untenable position.”

91. Joseph Fielding Smith, “Discusses Organic Evolution Opposed to Divine Revelation,” Church News Section, Deseret News, 24 July 1954, 4.

92. J. Reuben Clark, Jr., “When Are Church Leader’s [sic] Words Entitled to Claim of Scripture,” Church News Section, Deseret News, 31 July 1954, 11.

93. Truman G. Madsen, Philosophy Colloquium, Brigham Young University, Provo, 18 Oct. 1973, notes taken by Duane E. Jeffery, in Buerger, Bx 10, Fd 5.

94. Jeffery, “Seers, Savants and Evolution,” 75n86; reprinted in Session and Oberg, Search for Harmony, 186n54. See Duane E. Jeffery to Richard Hollingshaus, 25 Nov. 1975, located in Jeffery.