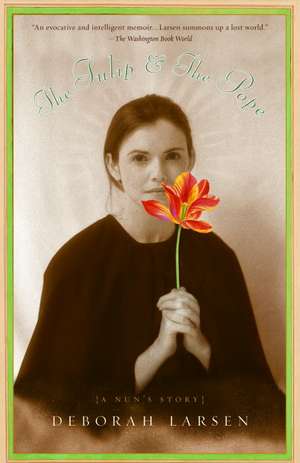

The Tulip and the Pope: A Nun's Story

Autor Deborah Larsenen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 aug 2006

Preț: 80.13 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 120

Preț estimativ în valută:

15.33€ • 15.84$ • 12.76£

15.33€ • 15.84$ • 12.76£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780375712906

ISBN-10: 0375712909

Pagini: 265

Dimensiuni: 134 x 205 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.21 kg

Ediția:Adnotată

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 0375712909

Pagini: 265

Dimensiuni: 134 x 205 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.21 kg

Ediția:Adnotată

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Notă biografică

Deborah Larsen grew up in Saint Paul, Minnesota, and currently lives in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. She teaches writing at Gettyburg College, where she holds the Merle S. Boyer Chair. She is the author of The White, a novel based on the life of Mary Jemison, and a collection of poetry, Stitching Porcelain. Her poems and short stories have appeared in The Nation, The Yale Review, and The New Yorker, among other publications.

Extras

Becoming a Postulant

Taxi

Blue smoke curled out of the taxicab windows.

The driver, who had just parked outside what looked like a stone mansion, waited; he had most likely been through this before. Three of us, three young women, sat in his Yellow Cab and smoked our cigarettes.

The mansion was the Motherhouse of the Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary. And this day, July 31, 1960, was Entrance Day, the day we would give our lives to God by joining the convent. About two weeks earlier, on the anniversary of the storming of the Bastille, on July 14, I had celebrated my nineteenth birthday.

Other taxicabs were pulling into the motherhouse like limousines to the Oscar awards or like horses to the Bar X corral. One hundred and eighteen of us wanted to become nuns.

Many of us were edgy and sat smoking and speculating a little, like starlets or cowpunchers before it was time to crush out the cigarettes or flick them away and do the next things that needed to be done.

Edgy, yes, we were—but also blithe to become nuns, just as Thomas More had been blithe to bare his neck and have his head neatly sliced off by the likes of the black-hooded executioner in A Man for All Seasons. Thomas was so chipper because he knew he was headed for God, would see God face-to-face. Robert Bolt has Thomas say—or maybe Thomas said it himself—that God “will not refuse one who is so blithe to go to him.”

In a way, we were going to Him now.

I was going to Him now. When I died, why would He refuse me if I had been a good nun? It was quite a bit like being a princess; eventually I would come into my own and inherit the transfigured earth and the kingdom of heaven.

Maybe the Yellow Cab driver, unless he was Catholic, actually did think he was my executioner. I would give him a big tip, all the money I had left, and I would give him the rest of my cigarettes.

The motherhouse, the convent of wine-colored stone, looked huge as a Cotswold manor house or an estate in Croton-on- Hudson. But the river at the base of the bluffs on which this building stood was the Mississippi, as it flowed past the southern edge of the city of Dubuque, Iowa.

In 1960 most of us didn’t know much about the path of the Mississippi or the life on it or where the bluffs began or ended. Did the river mostly remind us of the flux of all things, or even of Jim and Huck? It did not. It might have been the Tiber or the Loire, the Tigris, the Ruhr, or the Yangtze. No matter. What we wanted that day was to become nuns.

We didn’t give a fig about our position in the landscape.

Smoke

My friends Teresa (Tessa) and Kathleen (Kathy) and I thought of ourselves as savvy. We knew what to do because another friend’s sister, who was already a nun in the order we were joining, had told us the tradition. On Entrance Day we were to give our last cigarettes to the cabdriver.

We three had come in the Yellow Cab across a bridge over the river, from the train station in East Dubuque, Illinois. We had gotten on that train at Union Station in Saint Paul, Minnesota—our hometown.

Twelve young women in all had come from Minnesota to be nuns, but I knew Tessa and Kathy the best. I had been friends with Tessa since we were both about five years old. She had lovely black hair and an interesting, angular face and white teeth; some of her relatives had been actors; she was talented in art and she spoke her mind in an honest way. Kathy came from a large family and had brown hair; her eyes and her mouth worked together when she smiled, and we always felt we could trust her and her kindness.

A letter from what would be our new community had earlier asked that our parents please not drive us to Dubuque. The Sisters wanted to avoid what could always threaten to turn into weeping and the gnashing of teeth at their gates.

Just watch your daughter disappear through the doors of a convent. Try looking down at her feet in black flats walking away from you into the religious life. Better to put her on the train, the Burlington Northern, so that it felt like she was going off to college.

I sat in that cab and smoked two cigarettes at a time.

To be funny.

I thought I was being funny, trying to look frantic to smoke them all up, juggling the two lit cigarettes, Kents, in my ringless fingers. In the end, I would still have plenty of cigarettes left for my taxi driver, who undoubtedly watched us through his rearview mirror. I felt like a comedian.

We had smoked since freshman year in our all-girls Catholic high school, which was called Our Lady of Peace. We certainly weren’t allowed to smoke at Our Lady of Peace. But after school some of the bolder of us—not I—would walk a couple of blocks down Victoria Street to, say, Grand Avenue and step into their boyfriends’ ’55 Oldsmobile 98s or ’56 Chevrolets (which action was also not allowed by our school), and within thirty seconds the smoking started. Off they went, Bernadette inhaling, Tom exhaling; Patricia blowing smoke through her nose, Mark grasping the knob on his steering wheel to make a dashing left turn, a louie.

We had been instructed to bring only enough money to get us to the convent, and I must have tried to calculate it before I left home, which was on Goodrich Avenue in Saint Paul: so much for a ham sandwich and a Coke on the train, and maybe a Nut Goodie or a Mounds bar; so much for cab fare and tip—that was it.

And so we handed over that cab fare and that tip and the rest of our cigarettes, and that part was over. The cabdriver thanked us.

We thanked him. It was time, just the way it was “time” when the curtain went up in the high school plays in which we had acted. Mother Was a Freshman. The Song of Bernadette. The Little World of Don Camillo.

“It’s time, girls.”

We stopped laughing, got out of the cab, and walked up the sidewalk.

Several Sisters were at the door to welcome us. Even before I stepped over the threshold I felt relief from the heat. The motherhouse, I thought, was going to feel good compared to the muggy Iowa summer afternoon.

I had seen the motherhouse before but I had never been inside.

But Why

I had seen the motherhouse, Mount Carmel, because I had lived in Dubuque while I attended Clarke College for a year before I entered the convent. Some of my friends and I had driven across town to look around the convent grounds.

“What about waiting a year?” my parents had finally said when I told them I wanted to become a nun right after high school.

They had not stopped and stared; they had not winced; they had not blinked—although one time after I had sat holding one of my sister Judy’s newborns, my mother said, “I saw you looking at that baby.”

They just said, “Fine. But what about waiting a year?”

In the end, I waited and went to college for the academic year 1959–1960.

No one asked me why I wanted to be a nun. No one needed to ask, except the young Protestant couple who lived next door. I hadn’t known many Protestants, but I loved this couple.

“But why do you want to be a nun?” they would ask. (They, like most of us, had never heard of the older distinction between a Sister and a nun; the latter belonged to what was called a contemplative order, and was cloistered.) From the screened porch where they sat drinking Old-Fashioneds before dinner, they had watched me go out on date after date.

I would sigh.

Would Protestants understand how much you loved God? Could you speak to them about such a thing without their getting embarrassed?

Bashful

I loved God. Maybe I could have spoken to my neighbors in the language of the parts of scripture I loved best. In this way, it wouldn’t have sounded just like me. For I was bashful. I didn’t want to sound like myself—who was I, anyway?—or like some sentimental dope.

What other language did I have, really, besides the one that had been handed to me by the Church and the scriptures? The only ideas I had about God—the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost—would have come from tradition, from authority. It was important in those days that the words be sanctioned so I didn’t end up sounding bizarre or, worse, heretical, like the Arians, the Gnostics, or those southern French Albigensians who had been exterminated, according to the dictionary, during the Inquisition. The language of Holy Scripture, which I took to be the language of God and of the Roman Catholic Church—for the Church in a sense owned the whole Bible, I thought—was thrilling.

So if I had thought of it, I could have taken the Bible—for we had not memorized long passages in those days—and read from it to my neighbors. It would have been just like Readers’ Theatre, in which I had participated in high school.

In the beginning God created heaven and earth.

And the earth was void and empty, and darkness was upon the face of the deep; and the spirit of God moved over the waters.

I would continue reading aloud about how God created a light, which He called Day, and a darkness, which He called Night; about how the firmament came from His Hands and the creeping creatures and the great whales. The winged fowls and seeds that grew into herbs and trees would come next. And then man and woman, and the river that divided into the four heads of Phison, Gehon, Tigris, and Euphrates. I would read the part about how God brought the beasts and the fowls to Adam “to see what he would name them.”

Since God wanted “to see” what Adam would name them, I would eventually decide that God was quite a curious Person. Such curiosity on His part endeared Him to me, as did His allowing mere humans to name the things of this world.

How could you not adore the Person who had done all this? He made everything. He must have been something. Why does something exist and not nothing? Easy. Someone was kind enough to create it. He dreamt things up: you would never have thought of seeds, for instance. What you couldn’t do with seeds down through the ages! And herbs: he must have thought of something for healing and to flavor cooking. And Leviathan: all that baleen for straining plankton. What an imagination. Everything was absolutely original with Him, the Absolute.

You shrugged off all the cranky things God did in the Hebrew Bible—which most of us called the Old Testament in 1960—and you absolutely loved this Person, the One Whom you could just imagine moving over the waters. You wanted to live as close as you could to Him, live in His Shadow.

Why not dedicate yourself to Him as completely as you could? It was a cinch. Why didn’t millions of people do this every day, like the lemmings in the Arctic who sometimes grow so restless for something that they leave home and head downhill to wherever water is and think nothing of it.

“Because,” my mother would say. “Because if everyone entered religion”—in those days, in going into the convent or the monastery or the seminary, one “entered religion”—“eventually there would be no people.”

I took that as a joke. Or I took it to mean that she thought that the world needed marriage in order to produce little babies who would grow up to be people.

From the Hardcover edition.

Taxi

Blue smoke curled out of the taxicab windows.

The driver, who had just parked outside what looked like a stone mansion, waited; he had most likely been through this before. Three of us, three young women, sat in his Yellow Cab and smoked our cigarettes.

The mansion was the Motherhouse of the Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary. And this day, July 31, 1960, was Entrance Day, the day we would give our lives to God by joining the convent. About two weeks earlier, on the anniversary of the storming of the Bastille, on July 14, I had celebrated my nineteenth birthday.

Other taxicabs were pulling into the motherhouse like limousines to the Oscar awards or like horses to the Bar X corral. One hundred and eighteen of us wanted to become nuns.

Many of us were edgy and sat smoking and speculating a little, like starlets or cowpunchers before it was time to crush out the cigarettes or flick them away and do the next things that needed to be done.

Edgy, yes, we were—but also blithe to become nuns, just as Thomas More had been blithe to bare his neck and have his head neatly sliced off by the likes of the black-hooded executioner in A Man for All Seasons. Thomas was so chipper because he knew he was headed for God, would see God face-to-face. Robert Bolt has Thomas say—or maybe Thomas said it himself—that God “will not refuse one who is so blithe to go to him.”

In a way, we were going to Him now.

I was going to Him now. When I died, why would He refuse me if I had been a good nun? It was quite a bit like being a princess; eventually I would come into my own and inherit the transfigured earth and the kingdom of heaven.

Maybe the Yellow Cab driver, unless he was Catholic, actually did think he was my executioner. I would give him a big tip, all the money I had left, and I would give him the rest of my cigarettes.

The motherhouse, the convent of wine-colored stone, looked huge as a Cotswold manor house or an estate in Croton-on- Hudson. But the river at the base of the bluffs on which this building stood was the Mississippi, as it flowed past the southern edge of the city of Dubuque, Iowa.

In 1960 most of us didn’t know much about the path of the Mississippi or the life on it or where the bluffs began or ended. Did the river mostly remind us of the flux of all things, or even of Jim and Huck? It did not. It might have been the Tiber or the Loire, the Tigris, the Ruhr, or the Yangtze. No matter. What we wanted that day was to become nuns.

We didn’t give a fig about our position in the landscape.

Smoke

My friends Teresa (Tessa) and Kathleen (Kathy) and I thought of ourselves as savvy. We knew what to do because another friend’s sister, who was already a nun in the order we were joining, had told us the tradition. On Entrance Day we were to give our last cigarettes to the cabdriver.

We three had come in the Yellow Cab across a bridge over the river, from the train station in East Dubuque, Illinois. We had gotten on that train at Union Station in Saint Paul, Minnesota—our hometown.

Twelve young women in all had come from Minnesota to be nuns, but I knew Tessa and Kathy the best. I had been friends with Tessa since we were both about five years old. She had lovely black hair and an interesting, angular face and white teeth; some of her relatives had been actors; she was talented in art and she spoke her mind in an honest way. Kathy came from a large family and had brown hair; her eyes and her mouth worked together when she smiled, and we always felt we could trust her and her kindness.

A letter from what would be our new community had earlier asked that our parents please not drive us to Dubuque. The Sisters wanted to avoid what could always threaten to turn into weeping and the gnashing of teeth at their gates.

Just watch your daughter disappear through the doors of a convent. Try looking down at her feet in black flats walking away from you into the religious life. Better to put her on the train, the Burlington Northern, so that it felt like she was going off to college.

I sat in that cab and smoked two cigarettes at a time.

To be funny.

I thought I was being funny, trying to look frantic to smoke them all up, juggling the two lit cigarettes, Kents, in my ringless fingers. In the end, I would still have plenty of cigarettes left for my taxi driver, who undoubtedly watched us through his rearview mirror. I felt like a comedian.

We had smoked since freshman year in our all-girls Catholic high school, which was called Our Lady of Peace. We certainly weren’t allowed to smoke at Our Lady of Peace. But after school some of the bolder of us—not I—would walk a couple of blocks down Victoria Street to, say, Grand Avenue and step into their boyfriends’ ’55 Oldsmobile 98s or ’56 Chevrolets (which action was also not allowed by our school), and within thirty seconds the smoking started. Off they went, Bernadette inhaling, Tom exhaling; Patricia blowing smoke through her nose, Mark grasping the knob on his steering wheel to make a dashing left turn, a louie.

We had been instructed to bring only enough money to get us to the convent, and I must have tried to calculate it before I left home, which was on Goodrich Avenue in Saint Paul: so much for a ham sandwich and a Coke on the train, and maybe a Nut Goodie or a Mounds bar; so much for cab fare and tip—that was it.

And so we handed over that cab fare and that tip and the rest of our cigarettes, and that part was over. The cabdriver thanked us.

We thanked him. It was time, just the way it was “time” when the curtain went up in the high school plays in which we had acted. Mother Was a Freshman. The Song of Bernadette. The Little World of Don Camillo.

“It’s time, girls.”

We stopped laughing, got out of the cab, and walked up the sidewalk.

Several Sisters were at the door to welcome us. Even before I stepped over the threshold I felt relief from the heat. The motherhouse, I thought, was going to feel good compared to the muggy Iowa summer afternoon.

I had seen the motherhouse before but I had never been inside.

But Why

I had seen the motherhouse, Mount Carmel, because I had lived in Dubuque while I attended Clarke College for a year before I entered the convent. Some of my friends and I had driven across town to look around the convent grounds.

“What about waiting a year?” my parents had finally said when I told them I wanted to become a nun right after high school.

They had not stopped and stared; they had not winced; they had not blinked—although one time after I had sat holding one of my sister Judy’s newborns, my mother said, “I saw you looking at that baby.”

They just said, “Fine. But what about waiting a year?”

In the end, I waited and went to college for the academic year 1959–1960.

No one asked me why I wanted to be a nun. No one needed to ask, except the young Protestant couple who lived next door. I hadn’t known many Protestants, but I loved this couple.

“But why do you want to be a nun?” they would ask. (They, like most of us, had never heard of the older distinction between a Sister and a nun; the latter belonged to what was called a contemplative order, and was cloistered.) From the screened porch where they sat drinking Old-Fashioneds before dinner, they had watched me go out on date after date.

I would sigh.

Would Protestants understand how much you loved God? Could you speak to them about such a thing without their getting embarrassed?

Bashful

I loved God. Maybe I could have spoken to my neighbors in the language of the parts of scripture I loved best. In this way, it wouldn’t have sounded just like me. For I was bashful. I didn’t want to sound like myself—who was I, anyway?—or like some sentimental dope.

What other language did I have, really, besides the one that had been handed to me by the Church and the scriptures? The only ideas I had about God—the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost—would have come from tradition, from authority. It was important in those days that the words be sanctioned so I didn’t end up sounding bizarre or, worse, heretical, like the Arians, the Gnostics, or those southern French Albigensians who had been exterminated, according to the dictionary, during the Inquisition. The language of Holy Scripture, which I took to be the language of God and of the Roman Catholic Church—for the Church in a sense owned the whole Bible, I thought—was thrilling.

So if I had thought of it, I could have taken the Bible—for we had not memorized long passages in those days—and read from it to my neighbors. It would have been just like Readers’ Theatre, in which I had participated in high school.

In the beginning God created heaven and earth.

And the earth was void and empty, and darkness was upon the face of the deep; and the spirit of God moved over the waters.

I would continue reading aloud about how God created a light, which He called Day, and a darkness, which He called Night; about how the firmament came from His Hands and the creeping creatures and the great whales. The winged fowls and seeds that grew into herbs and trees would come next. And then man and woman, and the river that divided into the four heads of Phison, Gehon, Tigris, and Euphrates. I would read the part about how God brought the beasts and the fowls to Adam “to see what he would name them.”

Since God wanted “to see” what Adam would name them, I would eventually decide that God was quite a curious Person. Such curiosity on His part endeared Him to me, as did His allowing mere humans to name the things of this world.

How could you not adore the Person who had done all this? He made everything. He must have been something. Why does something exist and not nothing? Easy. Someone was kind enough to create it. He dreamt things up: you would never have thought of seeds, for instance. What you couldn’t do with seeds down through the ages! And herbs: he must have thought of something for healing and to flavor cooking. And Leviathan: all that baleen for straining plankton. What an imagination. Everything was absolutely original with Him, the Absolute.

You shrugged off all the cranky things God did in the Hebrew Bible—which most of us called the Old Testament in 1960—and you absolutely loved this Person, the One Whom you could just imagine moving over the waters. You wanted to live as close as you could to Him, live in His Shadow.

Why not dedicate yourself to Him as completely as you could? It was a cinch. Why didn’t millions of people do this every day, like the lemmings in the Arctic who sometimes grow so restless for something that they leave home and head downhill to wherever water is and think nothing of it.

“Because,” my mother would say. “Because if everyone entered religion”—in those days, in going into the convent or the monastery or the seminary, one “entered religion”—“eventually there would be no people.”

I took that as a joke. Or I took it to mean that she thought that the world needed marriage in order to produce little babies who would grow up to be people.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

"[An] evocative and intelligent memoir. . . .Larsen summons up a lost world."—The Washington Post Book World

"[Larsen] recalls . . .an era when life in a nunnery, for many woman, was the only counterculture available."—The New York Times

"Movingly and honestly explores an innocent girl's faith and subsequent coming-of-age."—Bookpage

"[Larsen] recalls . . .an era when life in a nunnery, for many woman, was the only counterculture available."—The New York Times

"Movingly and honestly explores an innocent girl's faith and subsequent coming-of-age."—Bookpage