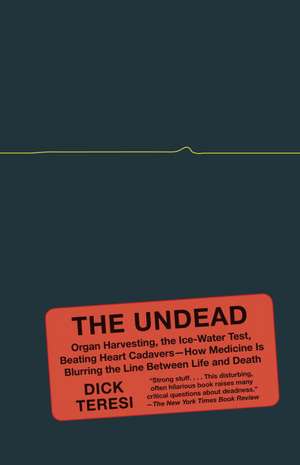

The Undead: Organ Harvesting, the Ice-Water Test, Beating-Heart Cadavers--How Medicine Is Blurring the Line Between Life and Death

Autor Dick Teresien Limba Engleză Paperback – 10 dec 2012

Preț: 103.28 lei

Preț vechi: 108.72 lei

-5% Nou

Puncte Express: 155

Preț estimativ în valută:

19.76€ • 20.64$ • 16.32£

19.76€ • 20.64$ • 16.32£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 25 martie-08 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400096114

ISBN-10: 1400096111

Pagini: 350

Dimensiuni: 135 x 203 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.28 kg

Editura: VINTAGE BOOKS

ISBN-10: 1400096111

Pagini: 350

Dimensiuni: 135 x 203 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.28 kg

Editura: VINTAGE BOOKS

Notă biografică

Dick Teresi is the author or coauthor of several books about science and technology, most recently The God Particle and Lost Discoveries: The Ancient Roots of Modern Science, both selected as New York Times Book Review notable books. He has been editor in chief of Science Digest, Longevity, VQ, and Omni, of which he was also a cofounder, and has written for The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, Smithsonian, The Atlantic, and Discover, among other publications.

Extras

Prologue

“B” Pod of the intensive care unit (ICU) at Baystate Medical Center is very bright: intense lights, everything painted in primary colors. Cabinets, counters, and chairs are a sparkling blue, obviously intended to be cheery, not sepulchral. A blue central stripe on the grayish linoleum floor leads us from room to room. There are three ICU pods at this Springfield, Massachusetts, hospital, each with three rooms arranged like spokes around a central station filled with computer terminals. Doctors and nurses come and go.

The patients in their separate rooms, like sickly fish in glass tanks arranged for observation, are largely slack-mouthed and gray or pale yellow in color. Most are fitted with clear plastic tubes the diameter of vacuum-cleaner hoses attached to their mouths. Most are old and gnarled, with sallow, sickly complex-ions. Sometimes one can see a bare concave chest or a yellowed foot sticking out from beneath a sheet. None is conversing.

We are not here to see them. We have come for the star of “B” Pod. We will call her Fernanda, a fifty-seven-year-old woman of Portuguese descent, who looks as though she might have just come back from a day at the mall. Her dark olive skin appears healthy against the sheets. Her features do not show the ravages of suffering or pain. Her eyes are closed beneath the heavy arched eyebrows. She has thick black eyelashes. Her wiry black hair with strands of gray is arranged neatly on the pillow. She has delicate legs and exquisite feet. Her face is serene; her chest rises and falls with the familiar rhythm of normal human breathing. She looks as if she had been put to sleep by a wicked queen in a fairy tale and needs only to be reanimated. Her vital signs, displayed on a monitor in squiggles the bright green of coloring books, are normal. She looks better than I do.

We are all there, including a group of medical students and interns, to watch Dr. Thomas Higgins pronounce Fernanda brain dead. She had been at work when coworkers found her on the fl oor and threw water on her face, a tactic that doesn’t work well against ischemic stroke. She probably had a brief headache, says Higgins, then fell unconscious. The ICU doctors at Baystate feel she will not recover. The brain-death team is about to make it official.

Those expecting space-age equipment, sophisticated brain scans, and the like, won’t find it. The exam is conducted mostly with tools you could find around your home: a flashlight, a Q-tip, some ice water. Her reflexes are tested. A light is shined in her eyes. Her head is turned from side to side. Cold water is squirted into an ear. She is disconnected from her ventilator to make sure she can’t breathe on her own. In less time than my ophthalmologist took to prescribe my last pair of bifocals, Fernanda is declared brain dead. That means she is legally dead, just as dead under the law as if her heart had stopped beating. Fernanda is then hooked back up to her ventilator to keep her organs fresh for transplant. Her heart continues to beat; her lungs continue to breathe. Though dead, she remains the best-looking patient in the ICU. The declaration of her death was more philosophical than physiological. A nurse says, “Whatever it was that made her her isn’t there anymore.”

ONE

Death Is Here to Stay

For all the accomplishments of molecular biology, we still can’t tell a live cat from a dead cat.

—Lynn Margulis

ARE YOU dead or alive? A dumb question, it would seem. If you’re reading this book, you are most likely alive. You know it, but do those in control know it? Will they acknowledge it? These are no longer stupid questions. The bar for being dead has been lowered. The bar for being considered alive has been raised. The old standards for life—Are you breathing? Is your heart beating? Are your cells still intact, not putrifying?—have been abandoned by the medical community in favor of a more demanding standard. Are you a person? Is what makes you you still intact? Can you prove it? Such concepts were previously the domain of philosophers and priests, but today it is doctors who determine our legal humanity. The dead are also not immune from judgment. A presidential council on bioethics recently determined that some dead people are less “healthy” than others. It is a different world.

This is a book about physical death. It began as a simple magazine article more than a decade ago, a report on the state of the art of death determination. I assumed I would find hightech medical equipment and techniques that would tell us when a human being had stopped living, that would pinpoint the moment that “what made her her” was gone. I eventually abandoned this goal and the article itself. Humans have long lived in denial about their own deaths, but I discovered that this denial has spread to the medical establishment, even to our beliefs about who is dead and who is alive. Our technology has not illuminated death; it has only expanded the breadth of our ignorance. Technology indicates that many of our assumptions about life and death, consciousness and unconsciousness, are wrong. Technology is telling us a great deal about our ignorance, but we are ignoring the information. My focus is scientific information about physiological death, but science and cultural factors often compete in an unproductive manner, canceling each other out. Though we have made technological advances, they often remain unused when it comes to dealing with the dying and dead, so cultural factors—philosophy, ethics, economics, religion—cannot be ignored.

Death, for most people, is not a comforting topic, and thus in the great mass of nonfiction literature devoted to the topic, death is treated as something that happens to someone else. My temptation is to write this as if I were narrating a dirigible explosion (“Oh, the humanity!”). Someone far away, perhaps in New Jersey, is dying. You, the audience, and I, the announcer, are merely witnesses. Let us reject that fiction. You, the reader, will die. If it is any consolation, keep in mind that I will also die. At my age, sooner rather than later.

###

During my research, I have spoken about death before groups of people on several occasions: to classes of college students, to groups of senior citizens, to people at dinner parties and other social gatherings. For the most part, those discussions have been disastrous. When I was talking at a dinner about the vagaries of brain death and the fact that our technology cannot ascertain the condition of most of the brain, one woman, a medical doctor, actually rose from her seat and yelled at me. She said that writing about this topic was “irresponsible,” that it would set organ donation back decades. She threatened to “call your editor.” In an undergraduate honors class at the University of Massachusetts, a senior premed major became angry with me when I spoke about patients in persistent vegetative state who show signs of consciousness. Her grandmother was in a comatose state, and her family was confused about what to do. The woman’s estate was dwindling because of her care, and, I gathered, so were the student’s hopes of paying for medical school. The premed student said that her grandmother was no longer “useful.” Those were two remarkable cases, but in general I made people uneasy, even angry. They defended their traditional ideas of life and death to me passionately, forcefully. My protestations that I was merely a journalist reporting facts as I found them, not making moral judgments, was of no consolation. I told the angry doctor that she could yank as many organs as she pleased out of people, and I would not stop or condemn her. I told the student that she and her family could pull the plug on Grandmother and I would not say a word. This just made them angrier. Not everyone was upset with the facts I presented. But those who were, were livid.

It was years before I figured out my apparent mistake. I assumed the information I was presenting, which threatens traditional views of death, was upsetting them. I now believe that it was something simpler: I was reminding people that they were going to die. Not someone else. Them.

In 1973, the cultural anthropologist Ernest Becker put forth an unusual thesis. In The Denial of Death, his Pulitzer Prizeߝwinning book, Becker said that humans are like other animals, with an evolutionary drive to survive. “Live! Live! Live!” our genes are screaming at us. Unlike other animals, however, said Becker, we humans know we cannot ultimately survive, that we will die. This dilemma, he believed, drives us mad. The awareness of our inevitable annihilation combined with our evolutionary program for self-preservation holds the potential for evoking paralyzing terror. Becker stated, “The result was the emergence of man as we know him: a hyperanxious animal who constantly invents reasons for anxiety even where there are none.” Becker wrote that man is terrified of death, and deals with this terror by denying death and keeping it unconscious. He felt that this terror directs a “substantial portion of human behavior,” according to one researcher.

Becker’s hypothesis was wide-sweeping. Death terror, he said, was the primary reason that humans created culture. Our religions, our political systems, our art, music, and literature—all this we have constructed “to assure ourselves that we have achieved something of lasting worth.” Becker said that “everything that man does in his symbolic world is an attempt to deny and overcome his grotesque fate. He literally drives himself into a blind obliviousness with social games, psychological tricks, personal preoccupations so far removed from the reality of his situation that they are forms of madness—agreed madness, shared madness, disguised and dignified madness, but madness all the same.” Those who delude themselves into believing they have achieved something of lasting worth would include, I assume, people who write books.

Becker’s theory was intriguing, plausible, and explained much of human behavior. Its only fl aw was that Becker had no concrete evidence. As a matter of fact, how would one even go about testing the hypothesis? Terror management was the superstring theory of anthropology—fascinating but not testable.

Help came long after Becker had resolved, by dying, his own death terror. In the late 1970s, three graduate students on an intramural bowling team at the University of Kansas began discussing death terror while the pins were being reset. Through the years, Jeff Greenberg, Tom Pyszczynski, and Sheldon Solomon translated Becker’s ideas into a formal theory that could be examined empirically. Their work culminated in a series of remarkable “mortality salience” experiments detailed in a 1997 paper.

Subjects were not told the true purpose of the experiment. Irrelevant questions and reading passages were included to mislead them. Embedded in an opening questionnaire, however, were these directions: “Please describe the emotions the thought of your own death arouses in you. Jot down, as specifically as you can, what you think will happen to you physically as you die and once you are physically dead.”

Greenberg, Pyszczynski, and Solomon used this and other techniques in different experiments, such as asking subjects to write their own obituaries or flashing the word “death” intermittently on a computer screen for twenty-eight milliseconds. In another case, the researchers used no verbal signals. They simply interviewed subjects in front of a funeral home. Control groups received no such death signals.

At the heart of the experiment were essays, pro-American and anti-American, supposedly written by foreign students studying in the United States but actually written by the psychologists. The pro essays stated that the United States was the greatest country in the world, the land of opportunity and freedom, and so on. The anti essays stated that American ideals were phony and the rich were getting richer, the poor poorer. Those subjects who were subjected to “mortality salience” ranked the pro essayist as extremely likable, and the anti essayist as extremely unlikable. The control group was not nearly so adamant. Greenberg et al. say that those who are made aware of their mortality need to offset their inner terror by defending their worldview and will praise to extremes those who hold the same worldview and denigrate those who hold different values.

“B” Pod of the intensive care unit (ICU) at Baystate Medical Center is very bright: intense lights, everything painted in primary colors. Cabinets, counters, and chairs are a sparkling blue, obviously intended to be cheery, not sepulchral. A blue central stripe on the grayish linoleum floor leads us from room to room. There are three ICU pods at this Springfield, Massachusetts, hospital, each with three rooms arranged like spokes around a central station filled with computer terminals. Doctors and nurses come and go.

The patients in their separate rooms, like sickly fish in glass tanks arranged for observation, are largely slack-mouthed and gray or pale yellow in color. Most are fitted with clear plastic tubes the diameter of vacuum-cleaner hoses attached to their mouths. Most are old and gnarled, with sallow, sickly complex-ions. Sometimes one can see a bare concave chest or a yellowed foot sticking out from beneath a sheet. None is conversing.

We are not here to see them. We have come for the star of “B” Pod. We will call her Fernanda, a fifty-seven-year-old woman of Portuguese descent, who looks as though she might have just come back from a day at the mall. Her dark olive skin appears healthy against the sheets. Her features do not show the ravages of suffering or pain. Her eyes are closed beneath the heavy arched eyebrows. She has thick black eyelashes. Her wiry black hair with strands of gray is arranged neatly on the pillow. She has delicate legs and exquisite feet. Her face is serene; her chest rises and falls with the familiar rhythm of normal human breathing. She looks as if she had been put to sleep by a wicked queen in a fairy tale and needs only to be reanimated. Her vital signs, displayed on a monitor in squiggles the bright green of coloring books, are normal. She looks better than I do.

We are all there, including a group of medical students and interns, to watch Dr. Thomas Higgins pronounce Fernanda brain dead. She had been at work when coworkers found her on the fl oor and threw water on her face, a tactic that doesn’t work well against ischemic stroke. She probably had a brief headache, says Higgins, then fell unconscious. The ICU doctors at Baystate feel she will not recover. The brain-death team is about to make it official.

Those expecting space-age equipment, sophisticated brain scans, and the like, won’t find it. The exam is conducted mostly with tools you could find around your home: a flashlight, a Q-tip, some ice water. Her reflexes are tested. A light is shined in her eyes. Her head is turned from side to side. Cold water is squirted into an ear. She is disconnected from her ventilator to make sure she can’t breathe on her own. In less time than my ophthalmologist took to prescribe my last pair of bifocals, Fernanda is declared brain dead. That means she is legally dead, just as dead under the law as if her heart had stopped beating. Fernanda is then hooked back up to her ventilator to keep her organs fresh for transplant. Her heart continues to beat; her lungs continue to breathe. Though dead, she remains the best-looking patient in the ICU. The declaration of her death was more philosophical than physiological. A nurse says, “Whatever it was that made her her isn’t there anymore.”

ONE

Death Is Here to Stay

For all the accomplishments of molecular biology, we still can’t tell a live cat from a dead cat.

—Lynn Margulis

ARE YOU dead or alive? A dumb question, it would seem. If you’re reading this book, you are most likely alive. You know it, but do those in control know it? Will they acknowledge it? These are no longer stupid questions. The bar for being dead has been lowered. The bar for being considered alive has been raised. The old standards for life—Are you breathing? Is your heart beating? Are your cells still intact, not putrifying?—have been abandoned by the medical community in favor of a more demanding standard. Are you a person? Is what makes you you still intact? Can you prove it? Such concepts were previously the domain of philosophers and priests, but today it is doctors who determine our legal humanity. The dead are also not immune from judgment. A presidential council on bioethics recently determined that some dead people are less “healthy” than others. It is a different world.

This is a book about physical death. It began as a simple magazine article more than a decade ago, a report on the state of the art of death determination. I assumed I would find hightech medical equipment and techniques that would tell us when a human being had stopped living, that would pinpoint the moment that “what made her her” was gone. I eventually abandoned this goal and the article itself. Humans have long lived in denial about their own deaths, but I discovered that this denial has spread to the medical establishment, even to our beliefs about who is dead and who is alive. Our technology has not illuminated death; it has only expanded the breadth of our ignorance. Technology indicates that many of our assumptions about life and death, consciousness and unconsciousness, are wrong. Technology is telling us a great deal about our ignorance, but we are ignoring the information. My focus is scientific information about physiological death, but science and cultural factors often compete in an unproductive manner, canceling each other out. Though we have made technological advances, they often remain unused when it comes to dealing with the dying and dead, so cultural factors—philosophy, ethics, economics, religion—cannot be ignored.

Death, for most people, is not a comforting topic, and thus in the great mass of nonfiction literature devoted to the topic, death is treated as something that happens to someone else. My temptation is to write this as if I were narrating a dirigible explosion (“Oh, the humanity!”). Someone far away, perhaps in New Jersey, is dying. You, the audience, and I, the announcer, are merely witnesses. Let us reject that fiction. You, the reader, will die. If it is any consolation, keep in mind that I will also die. At my age, sooner rather than later.

###

During my research, I have spoken about death before groups of people on several occasions: to classes of college students, to groups of senior citizens, to people at dinner parties and other social gatherings. For the most part, those discussions have been disastrous. When I was talking at a dinner about the vagaries of brain death and the fact that our technology cannot ascertain the condition of most of the brain, one woman, a medical doctor, actually rose from her seat and yelled at me. She said that writing about this topic was “irresponsible,” that it would set organ donation back decades. She threatened to “call your editor.” In an undergraduate honors class at the University of Massachusetts, a senior premed major became angry with me when I spoke about patients in persistent vegetative state who show signs of consciousness. Her grandmother was in a comatose state, and her family was confused about what to do. The woman’s estate was dwindling because of her care, and, I gathered, so were the student’s hopes of paying for medical school. The premed student said that her grandmother was no longer “useful.” Those were two remarkable cases, but in general I made people uneasy, even angry. They defended their traditional ideas of life and death to me passionately, forcefully. My protestations that I was merely a journalist reporting facts as I found them, not making moral judgments, was of no consolation. I told the angry doctor that she could yank as many organs as she pleased out of people, and I would not stop or condemn her. I told the student that she and her family could pull the plug on Grandmother and I would not say a word. This just made them angrier. Not everyone was upset with the facts I presented. But those who were, were livid.

It was years before I figured out my apparent mistake. I assumed the information I was presenting, which threatens traditional views of death, was upsetting them. I now believe that it was something simpler: I was reminding people that they were going to die. Not someone else. Them.

In 1973, the cultural anthropologist Ernest Becker put forth an unusual thesis. In The Denial of Death, his Pulitzer Prizeߝwinning book, Becker said that humans are like other animals, with an evolutionary drive to survive. “Live! Live! Live!” our genes are screaming at us. Unlike other animals, however, said Becker, we humans know we cannot ultimately survive, that we will die. This dilemma, he believed, drives us mad. The awareness of our inevitable annihilation combined with our evolutionary program for self-preservation holds the potential for evoking paralyzing terror. Becker stated, “The result was the emergence of man as we know him: a hyperanxious animal who constantly invents reasons for anxiety even where there are none.” Becker wrote that man is terrified of death, and deals with this terror by denying death and keeping it unconscious. He felt that this terror directs a “substantial portion of human behavior,” according to one researcher.

Becker’s hypothesis was wide-sweeping. Death terror, he said, was the primary reason that humans created culture. Our religions, our political systems, our art, music, and literature—all this we have constructed “to assure ourselves that we have achieved something of lasting worth.” Becker said that “everything that man does in his symbolic world is an attempt to deny and overcome his grotesque fate. He literally drives himself into a blind obliviousness with social games, psychological tricks, personal preoccupations so far removed from the reality of his situation that they are forms of madness—agreed madness, shared madness, disguised and dignified madness, but madness all the same.” Those who delude themselves into believing they have achieved something of lasting worth would include, I assume, people who write books.

Becker’s theory was intriguing, plausible, and explained much of human behavior. Its only fl aw was that Becker had no concrete evidence. As a matter of fact, how would one even go about testing the hypothesis? Terror management was the superstring theory of anthropology—fascinating but not testable.

Help came long after Becker had resolved, by dying, his own death terror. In the late 1970s, three graduate students on an intramural bowling team at the University of Kansas began discussing death terror while the pins were being reset. Through the years, Jeff Greenberg, Tom Pyszczynski, and Sheldon Solomon translated Becker’s ideas into a formal theory that could be examined empirically. Their work culminated in a series of remarkable “mortality salience” experiments detailed in a 1997 paper.

Subjects were not told the true purpose of the experiment. Irrelevant questions and reading passages were included to mislead them. Embedded in an opening questionnaire, however, were these directions: “Please describe the emotions the thought of your own death arouses in you. Jot down, as specifically as you can, what you think will happen to you physically as you die and once you are physically dead.”

Greenberg, Pyszczynski, and Solomon used this and other techniques in different experiments, such as asking subjects to write their own obituaries or flashing the word “death” intermittently on a computer screen for twenty-eight milliseconds. In another case, the researchers used no verbal signals. They simply interviewed subjects in front of a funeral home. Control groups received no such death signals.

At the heart of the experiment were essays, pro-American and anti-American, supposedly written by foreign students studying in the United States but actually written by the psychologists. The pro essays stated that the United States was the greatest country in the world, the land of opportunity and freedom, and so on. The anti essays stated that American ideals were phony and the rich were getting richer, the poor poorer. Those subjects who were subjected to “mortality salience” ranked the pro essayist as extremely likable, and the anti essayist as extremely unlikable. The control group was not nearly so adamant. Greenberg et al. say that those who are made aware of their mortality need to offset their inner terror by defending their worldview and will praise to extremes those who hold the same worldview and denigrate those who hold different values.

Recenzii

“Strong stuff. . . . This disturbing, often hilarious book raises many critical questions about deadness.”

—The New York Times Book Review

“Reading Dick Teresi’s book is like discovering that your college class has been hijacked by the spitball-lobbing kid in the back row—and that the kid is twice as smart as the prof ever was. . . . Taking on biologists, philosophers, and the medical establishment, Teresi zestfully skewers our confused thinking about life, death, and the states in between. A pleasure to read.”

—Charles C. Mann, author of 1493 and 1491

“An indefatigable researcher and fluid writer, Mr. Teresi provides a good long riff on death past and present.”

—The New York Times

“Charting historical definitions of death, the thinking of research greats and debates over near-death experiences, Teresi notes that the ethical challenges are immense, asking, for instance, whether all organ donors are unrevivable.”

—Nature

“The simple question Teresi asks is: ‘When exactly is a person dead?’ Prepare to have your assumptions shattered.”

—The Globe and Mail (UK)

“Chilling, controversial, and, at times, comical commentary on physical death…All sorts of experts—on coma, animal euthanasia, and execution—as well as undertakers, organ transplant staff, neurologists, ethicists, and lawyers weigh-in on the death debate.”

—Booklist

“As I was pulled into this startling, informative account of death-defying and death-defining, I couldn’t help putting a checkmark in the margin next to every line that made me gasp—or laugh—or marvel at Dick Teresi’s bold, inimitable reporting style. On some pages I made as many as four checkmarks. The book left me reeling at the welter of uncertainty that surrounds the certainty of death.”

—Dava Sobel, author of Longitude and A More Perfect Heaven

“Like a real-life version of Robin Cook’s medical thriller Coma, Teresi paints a grisly picture of organ harvesting and raises uncomfortable questions: Is the donor actually dead rather than at the point of death? Might he or she be revived given time and proper medical attention?. . . . Provocative. . . . [An] examination of important ethical issues and the still-unresolved question of what constitutes death.”

—Kirkus Reviews

—The New York Times Book Review

“Reading Dick Teresi’s book is like discovering that your college class has been hijacked by the spitball-lobbing kid in the back row—and that the kid is twice as smart as the prof ever was. . . . Taking on biologists, philosophers, and the medical establishment, Teresi zestfully skewers our confused thinking about life, death, and the states in between. A pleasure to read.”

—Charles C. Mann, author of 1493 and 1491

“An indefatigable researcher and fluid writer, Mr. Teresi provides a good long riff on death past and present.”

—The New York Times

“Charting historical definitions of death, the thinking of research greats and debates over near-death experiences, Teresi notes that the ethical challenges are immense, asking, for instance, whether all organ donors are unrevivable.”

—Nature

“The simple question Teresi asks is: ‘When exactly is a person dead?’ Prepare to have your assumptions shattered.”

—The Globe and Mail (UK)

“Chilling, controversial, and, at times, comical commentary on physical death…All sorts of experts—on coma, animal euthanasia, and execution—as well as undertakers, organ transplant staff, neurologists, ethicists, and lawyers weigh-in on the death debate.”

—Booklist

“As I was pulled into this startling, informative account of death-defying and death-defining, I couldn’t help putting a checkmark in the margin next to every line that made me gasp—or laugh—or marvel at Dick Teresi’s bold, inimitable reporting style. On some pages I made as many as four checkmarks. The book left me reeling at the welter of uncertainty that surrounds the certainty of death.”

—Dava Sobel, author of Longitude and A More Perfect Heaven

“Like a real-life version of Robin Cook’s medical thriller Coma, Teresi paints a grisly picture of organ harvesting and raises uncomfortable questions: Is the donor actually dead rather than at the point of death? Might he or she be revived given time and proper medical attention?. . . . Provocative. . . . [An] examination of important ethical issues and the still-unresolved question of what constitutes death.”

—Kirkus Reviews