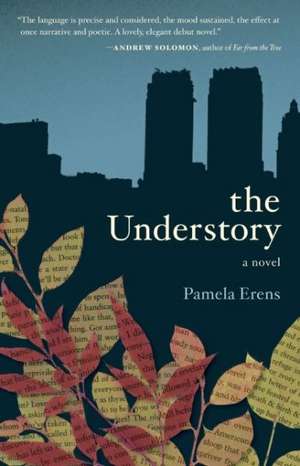

The Understory

Autor Pamela Erensen Limba Engleză Paperback – 14 apr 2014

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

L.A. Times Book Prize (2007), Saroyan Writing Prize (2008)

The Understory—the debut novel from the critically acclaimed author of The Virgins—is the haunting portrayal of Jack Gorse, an ex-lawyer, now unemployed, who walls off his inner life with elaborate rituals and routines. Every day he takes the same walk from his Upper West Side apartment to the Brooklyn Bridge. He follows the same path through Central Park; he stops to browse in the same bookstore, to eat lunch in the same diner. Threatened with eviction from his longtime apartment and caught off-guard by an attraction to a near stranger, Gorse takes steps that lead to the dramatic dissolution of the only existence he’s known. As the narrative alternates between his days in New York City and his present life in a Vermont Buddhist Monastery, The Understory unfolds as both a mystery and a psychological study, revealing that repression and self-expression can be equally destructive.

Preț: 84.93 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 127

Preț estimativ în valută:

16.25€ • 17.00$ • 13.50£

16.25€ • 17.00$ • 13.50£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781935639855

ISBN-10: 1935639854

Pagini: 172

Dimensiuni: 130 x 198 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Ediția:2

Editura: Tin House Books

ISBN-10: 1935639854

Pagini: 172

Dimensiuni: 130 x 198 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Ediția:2

Editura: Tin House Books

Recenzii

“I am amazed and moved by Pamela Erens’s The Understory. It brings to mind (and stands up well next to) such literary ancestors as Hamsun's Hunger, or Beckett's stories of the evicted, but it is uniquely tender in its treatment of the isolated mind's quest to keep alive what is most radiant and most fragile in the face of the brutal catastrophe of reality. Erens brings extraordinary powers of empathy and technical mastery to the character of Jack Gorse—normally the person we pass on the street and, after a token moment of pity, attempt to forget as rapidly as possible. In this book there is no turning away from him, or more accurately and terribly, from the world as he perceives it.”

— Franz Wright, author of Walking to Martha's Vineyard, winner of the Pulitzer Prize

“This is a strange, haunting meditation on aloneness and the melancholy of frustrated love, written knowingly about a character bereft of self-knowledge. The language is precise and considered, the mood sustained, the effect at once narrative and poetic. A lovely, elegant debut novel.”

— Andrew Solomon, author of The Noonday Demon, winner of the National Book Award, and Far From the Tree, winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award

“A wonderfully controlled portrait of a contemporary Underground Man — a man who buries his life beneath the normal social interactions of modern-day Manhattan, so that what is inside of him might stay buried too.”

— Jonathan Dee, author of The Privileges, a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize

“Pamela Erens's The Understory is at once an exquisite portrait of a man driven by forces beyond his control, an homage to Manhattan's secret places, and a deftly braided narrative that keeps the reader hungry to find out what happens next.”

—Rilla Askew, author of Fire in Beulah, winner of the American Book Award

"Erens follows this haggard, lonely man in his unremarkable every day without missing a detail...This solitary man who cannot connect even in a crowd, eventually implodes, and explodes, and the sense of following him through this process is a literary meditation I will long not forget. It is for this kind of fine literature that I hunger all my reading life, and find all too rarely."

—Zinta Aistars, Gently Read Literature

“Hauntingly abject…skillfully rendered…a sensitive, restrained debut.”

—Publishers Weekly

“Mesmerizing…a universal human cry for love.”

—ForeWord Magazine

“An elegant, understated study of physical and psychic dislocations…artfully detailed and beautifully rendered.”

—the Chicago Tribune

"This is storytelling at its finest, lightest and most complex. I enjoyed every moment of the time Jack and I spent together. I let my tea go cold as he talked. I hope one day we meet again, although, because of the way things go, I doubt we will."

—LitReactor

“Not your typical debut…The soul of this novel is its meditative lyricism, rendered in language that is as exquisite as it is penetrating.”

—Small Spiral Notebook

"The novel is a psychological study with an ending that will shock you."

—BookTrib

“The Understory comes to a gripping finale. Erens…is a very talented writer, and this slender volume is a welcome addition to contemporary fiction.”

—Gay & Lesbian Review Worldwide

“This novel derives its power from Erens' ability to create a character who is simultaneously repulsive and sympathetic…. [She has] given us insight into the very human desire to make this world — and our lives — matter.”

—El Paso Times

“Pamela Erens’s novel is a letter bomb of a book, pulsing with savage potency.”

—The Elegant Variation

“We have such a deep understanding of and sympathy for the engaging but troubled Jack that we willingly follow him into the dark corners of his wounded psyche.”

—Rain Taxi

“In a book that begs for stellar acting in a cinematic treatment, the fascinated reader bears witness as events follow a collision course.”

—Booklist

— Franz Wright, author of Walking to Martha's Vineyard, winner of the Pulitzer Prize

“This is a strange, haunting meditation on aloneness and the melancholy of frustrated love, written knowingly about a character bereft of self-knowledge. The language is precise and considered, the mood sustained, the effect at once narrative and poetic. A lovely, elegant debut novel.”

— Andrew Solomon, author of The Noonday Demon, winner of the National Book Award, and Far From the Tree, winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award

“A wonderfully controlled portrait of a contemporary Underground Man — a man who buries his life beneath the normal social interactions of modern-day Manhattan, so that what is inside of him might stay buried too.”

— Jonathan Dee, author of The Privileges, a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize

“Pamela Erens's The Understory is at once an exquisite portrait of a man driven by forces beyond his control, an homage to Manhattan's secret places, and a deftly braided narrative that keeps the reader hungry to find out what happens next.”

—Rilla Askew, author of Fire in Beulah, winner of the American Book Award

"Erens follows this haggard, lonely man in his unremarkable every day without missing a detail...This solitary man who cannot connect even in a crowd, eventually implodes, and explodes, and the sense of following him through this process is a literary meditation I will long not forget. It is for this kind of fine literature that I hunger all my reading life, and find all too rarely."

—Zinta Aistars, Gently Read Literature

“Hauntingly abject…skillfully rendered…a sensitive, restrained debut.”

—Publishers Weekly

“Mesmerizing…a universal human cry for love.”

—ForeWord Magazine

“An elegant, understated study of physical and psychic dislocations…artfully detailed and beautifully rendered.”

—the Chicago Tribune

"This is storytelling at its finest, lightest and most complex. I enjoyed every moment of the time Jack and I spent together. I let my tea go cold as he talked. I hope one day we meet again, although, because of the way things go, I doubt we will."

—LitReactor

“Not your typical debut…The soul of this novel is its meditative lyricism, rendered in language that is as exquisite as it is penetrating.”

—Small Spiral Notebook

"The novel is a psychological study with an ending that will shock you."

—BookTrib

“The Understory comes to a gripping finale. Erens…is a very talented writer, and this slender volume is a welcome addition to contemporary fiction.”

—Gay & Lesbian Review Worldwide

“This novel derives its power from Erens' ability to create a character who is simultaneously repulsive and sympathetic…. [She has] given us insight into the very human desire to make this world — and our lives — matter.”

—El Paso Times

“Pamela Erens’s novel is a letter bomb of a book, pulsing with savage potency.”

—The Elegant Variation

“We have such a deep understanding of and sympathy for the engaging but troubled Jack that we willingly follow him into the dark corners of his wounded psyche.”

—Rain Taxi

“In a book that begs for stellar acting in a cinematic treatment, the fascinated reader bears witness as events follow a collision course.”

—Booklist

Notă biografică

Pamela Erens’s first novel, The Understory was a finalist for both the 2007 Los Angeles Times Book Prize for First Fiction and the William Saroyan International Prize for Writing. Her widely-acclaimed second novel, The Virgins was a New York Times and Chicago Tribune Editors' Choice. For many years she worked as a magazine editor, including Glamour. She lives in Maplewood, NJ.

Extras

Chapter One

Many years ago, in a deli, I found flaky white bits floating in my self-serve coffee; the milk, sitting all day in a bucket of cold water, had turned sour. Since that day I have never drunk my coffee anything but black. Yet I look for those tainted curls every time: I pour, peer inside to reassure myself, then top it off.

Even here I am bound to my habits. I pour, pause, bend to my mug. All at once Joku is standing next to me at the end of the buffet table. He looks down, as if he too suspects that something is wrong with my drink. I move the mug away, toward me, and by the time I have accomplished this I’ve forgotten my most recent action. Did I already look inside? I think so, but it nags at me that I don’t know for sure. The glass coffeepot, suspended above the mug, is beginning to hurt my wrist. Joku is watching me now, and I become even more flustered and uncomfortable. To look twice is not good, not the way things should be, but I decide it is better than failing to look at all. So I glance in, confirm that the surface of the coffee is black and pure, then finish filling the mug and replace the pot on the electric hot plate. Joku moves off, toward the metal trays of kidney beans and homemade bread and peanut butter.

Normally his staring wouldn’t rattle me so much. I have grown used to it. He watches me in the dining hall, during chores, as we file into the meditation hall for zazen. He is so open about it, does not spy or hide. His head turns as we pass in the hallways. Without a doubt the abbot has asked him to keep tabs on me. For what if I am mentally unbalanced, a troublemaker? But today was different. Today Joku came so close that he nearly touched me.

He was the first person I met here, with the exception of the secretary. I was dirty from the night in the park and the day on the bus, and the red itchy blossoms on my neck and arms tormented me. Warily the secretary invited me in out of the snow, but I stayed under the eaves next to the large oak door with its brass doorknob while she ran to see what was to be done about me. It was only on the last leg of the trip that the snow had begun. When I’d left Manhattan it had been spring, but now, three hundred miles north, it was winter again, the land knocked back into dormancy. The sun was setting and I watched the spruce and firs below the hill sink into darkness. Then a small man in a dark robe came to the entrance. He had a broad, intelligent face and wire-rimmed glasses. I guessed him to be ten years older than I was, around fifty. “Mr. Ronan?” he asked. “My name is Joku.” He flung his hand toward the open door, indicating that I had been received, admitted. His gesture was too big; the back of his hand hit the door, made a leaden thud.

He led me through the simple corridors—unsanded beams, white plaster, flowers set in a wall alcove. I pictured Patrick passing through these hallways and wanted to reach out to touch the walls that he might have touched, but we were moving quickly and I did not want to call attention to myself. We arrived at a small office and the monk introduced me to the abbot, a tall man with a long, elegant head who sat at a desk bare of papers. The monk withdrew to the side of the room but could not seem to make himself unobtrusive. He shuffled, coughed, knocked over something on a table.

“Are you interested in our practice?” asked the abbot, resting his arms upon his desk. I had not expected him to look and sound so perfectly American. His voice had a Yankee timbre, the elegant head a Yankee frigidity. I answered that I didn’t know. I repeated what I had said to the secretary, that I had no home, no place to stay. I waited to be asked for more details. But the abbot only handed me a folded piece of paper and told the monk to find me a bed. And so I was taken to a room with four bunk beds and given a pillow and a small rough towel. Looking at the beds, I could already feel the nearness of the bodies that would lie in them tonight. Snow drizzled steadily outside the window. The fire under my skin brought water to my eyes and I slapped heavily at my arms, then pushed up my sleeve to show the monk that there was a reason, that it wasn’t craziness. His eyes widened. “What is it?” he asked.

“Nothing contagious,” I assured him. “An allergic reaction.”

“I will find something for you,” he told me.

The room was empty and quiet; the whole building was quiet. I looked at the paper the abbot had given me. It spelled out the abbey’s policy on nonpaying visitors. Short-term residencies would be permitted in exchange for twenty hours of labor a week. A list followed; I was to check off any areas in which I had special skill. Cooking. Computers. Communications. Gardening. And so on. Across the list I scrawled the word none. Then I erased that—better to appear useful—and put a check mark next to Gardening.

The monk came back with a crumpled tube. “Tch, tch,” he clucked as I patted the ointment on. A strange, sorrowful little noise. I sighed as the cool salve penetrated the skin.

“We rise at four,” said the monk. “Just follow the others.”

“My name is Gorse, actually.”

“Pardon me?” He stopped at the door.

“I said Ronan but that’s not correct. My name is Gorse, Jack Gorse.”

“Mr. Gorse, then. Pleased to meet you.”

I was afraid he would hold out his hand. The fleshiness of a handshake has always repelled me, hands slickly moist or hot like a furnace. But he only bowed, Buddhist-style, his thick palms pressed together. He told me to make myself comfortable, and added that the others would be back in half an hour. The lights would be turned out at nine.

It felt good to have a bed. I fell asleep before the others returned.

Many years ago, in a deli, I found flaky white bits floating in my self-serve coffee; the milk, sitting all day in a bucket of cold water, had turned sour. Since that day I have never drunk my coffee anything but black. Yet I look for those tainted curls every time: I pour, peer inside to reassure myself, then top it off.

Even here I am bound to my habits. I pour, pause, bend to my mug. All at once Joku is standing next to me at the end of the buffet table. He looks down, as if he too suspects that something is wrong with my drink. I move the mug away, toward me, and by the time I have accomplished this I’ve forgotten my most recent action. Did I already look inside? I think so, but it nags at me that I don’t know for sure. The glass coffeepot, suspended above the mug, is beginning to hurt my wrist. Joku is watching me now, and I become even more flustered and uncomfortable. To look twice is not good, not the way things should be, but I decide it is better than failing to look at all. So I glance in, confirm that the surface of the coffee is black and pure, then finish filling the mug and replace the pot on the electric hot plate. Joku moves off, toward the metal trays of kidney beans and homemade bread and peanut butter.

Normally his staring wouldn’t rattle me so much. I have grown used to it. He watches me in the dining hall, during chores, as we file into the meditation hall for zazen. He is so open about it, does not spy or hide. His head turns as we pass in the hallways. Without a doubt the abbot has asked him to keep tabs on me. For what if I am mentally unbalanced, a troublemaker? But today was different. Today Joku came so close that he nearly touched me.

He was the first person I met here, with the exception of the secretary. I was dirty from the night in the park and the day on the bus, and the red itchy blossoms on my neck and arms tormented me. Warily the secretary invited me in out of the snow, but I stayed under the eaves next to the large oak door with its brass doorknob while she ran to see what was to be done about me. It was only on the last leg of the trip that the snow had begun. When I’d left Manhattan it had been spring, but now, three hundred miles north, it was winter again, the land knocked back into dormancy. The sun was setting and I watched the spruce and firs below the hill sink into darkness. Then a small man in a dark robe came to the entrance. He had a broad, intelligent face and wire-rimmed glasses. I guessed him to be ten years older than I was, around fifty. “Mr. Ronan?” he asked. “My name is Joku.” He flung his hand toward the open door, indicating that I had been received, admitted. His gesture was too big; the back of his hand hit the door, made a leaden thud.

He led me through the simple corridors—unsanded beams, white plaster, flowers set in a wall alcove. I pictured Patrick passing through these hallways and wanted to reach out to touch the walls that he might have touched, but we were moving quickly and I did not want to call attention to myself. We arrived at a small office and the monk introduced me to the abbot, a tall man with a long, elegant head who sat at a desk bare of papers. The monk withdrew to the side of the room but could not seem to make himself unobtrusive. He shuffled, coughed, knocked over something on a table.

“Are you interested in our practice?” asked the abbot, resting his arms upon his desk. I had not expected him to look and sound so perfectly American. His voice had a Yankee timbre, the elegant head a Yankee frigidity. I answered that I didn’t know. I repeated what I had said to the secretary, that I had no home, no place to stay. I waited to be asked for more details. But the abbot only handed me a folded piece of paper and told the monk to find me a bed. And so I was taken to a room with four bunk beds and given a pillow and a small rough towel. Looking at the beds, I could already feel the nearness of the bodies that would lie in them tonight. Snow drizzled steadily outside the window. The fire under my skin brought water to my eyes and I slapped heavily at my arms, then pushed up my sleeve to show the monk that there was a reason, that it wasn’t craziness. His eyes widened. “What is it?” he asked.

“Nothing contagious,” I assured him. “An allergic reaction.”

“I will find something for you,” he told me.

The room was empty and quiet; the whole building was quiet. I looked at the paper the abbot had given me. It spelled out the abbey’s policy on nonpaying visitors. Short-term residencies would be permitted in exchange for twenty hours of labor a week. A list followed; I was to check off any areas in which I had special skill. Cooking. Computers. Communications. Gardening. And so on. Across the list I scrawled the word none. Then I erased that—better to appear useful—and put a check mark next to Gardening.

The monk came back with a crumpled tube. “Tch, tch,” he clucked as I patted the ointment on. A strange, sorrowful little noise. I sighed as the cool salve penetrated the skin.

“We rise at four,” said the monk. “Just follow the others.”

“My name is Gorse, actually.”

“Pardon me?” He stopped at the door.

“I said Ronan but that’s not correct. My name is Gorse, Jack Gorse.”

“Mr. Gorse, then. Pleased to meet you.”

I was afraid he would hold out his hand. The fleshiness of a handshake has always repelled me, hands slickly moist or hot like a furnace. But he only bowed, Buddhist-style, his thick palms pressed together. He told me to make myself comfortable, and added that the others would be back in half an hour. The lights would be turned out at nine.

It felt good to have a bed. I fell asleep before the others returned.

Premii

- L.A. Times Book Prize Finalist, 2007

- Saroyan Writing Prize Finalist, 2008