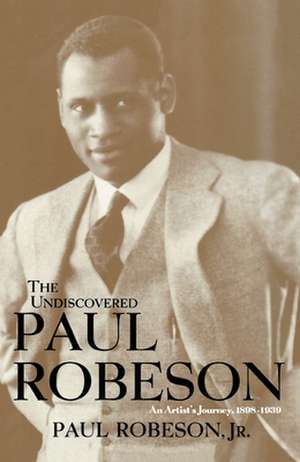

The Undiscovered Paul Robeson, an Artist's Journey, 1898-1939

Autor Jr. Robeson, Paul, ROBESONen Limba Engleză Hardback – 26 mar 2001

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

Hurston/Wright LEGACY Award (2002)

The greatest scholar–athlete–performing artist in U.S. history, Paul Robeson was one of the most compelling figures of the twentieth century.

Now his son, Paul Robeson Jr., traces the dramatic arc of his rise to fame, painting a definitive picture of Paul Robeson′s formative years. His father was an escaped slave; his mother, a descendent of freedmen; and his wife, the brilliant and ambitious Eslanda Cardozo Goode. With a law degree from Columbia University; a professional football career; title roles in Eugene O′Neill′s plays and in Shakespeare′s Othello; and a concert career in America and Europe, Robeson dominated his era.

This unprecedented biography reveals the depth of Robeson′s cultural scholarship, explores the contradictions he bridged in his personal and political life, and describes his emergence as a symbol of the anticolonial and antifascist struggles. Filled with previously unpublished photographs and source materials from the private diaries and letters of Paul and Eslanda Robeson, this is the epic story of a forerunner who now stands as one of America′s greatest heroes.

Preț: 236.46 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 355

Preț estimativ în valută:

45.25€ • 48.38$ • 37.73£

45.25€ • 48.38$ • 37.73£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 27 martie-10 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780471242659

ISBN-10: 0471242659

Pagini: 400

Dimensiuni: 162 x 241 x 33 mm

Greutate: 0.71 kg

Editura: Wiley

Locul publicării:Hoboken, United States

ISBN-10: 0471242659

Pagini: 400

Dimensiuni: 162 x 241 x 33 mm

Greutate: 0.71 kg

Editura: Wiley

Locul publicării:Hoboken, United States

Cuprins

Preface: Paul Robeson: "I Am Myself".

MOTHERLESS CHILD (1898–1919).

The Preacher′s Son (1898–1915).

In His Glory: Robeson of Rutgers (1915–1919).

DESTINY AND DECISION (1919–1926).

Essie (1919–1921).

A Taste of Theater (1922).

The Performer Triumphs (1923–1924).

Seeker of Grace (1925–1926).

FROM PERFORMER TO ARTIST (1926–1932).

"Ol′ Man River" (1926–1928).

"The Power to Create Beauty" (1928–1929).

To Feed His Soul (1930).

Troubled Spirit (1930–1931).

Giver of Grace (1931–1932).

TRIBUNE OF A CULTURE (1933–1936).

Film and the Politics of Culture (1933–1934).

Test Run: London–Moscow–Hollywood (1934–1935).

White Film, Black Culture (1936).

TO BE A PROPHET (1936–1939).

Russia′s Sun: Stalin′s Shadow (1936–1937).

Spain′s Ramparts: "The Artist Must Elect" (1938).

A Home in That Rock (1938–1939).

Notes.

Index.

MOTHERLESS CHILD (1898–1919).

The Preacher′s Son (1898–1915).

In His Glory: Robeson of Rutgers (1915–1919).

DESTINY AND DECISION (1919–1926).

Essie (1919–1921).

A Taste of Theater (1922).

The Performer Triumphs (1923–1924).

Seeker of Grace (1925–1926).

FROM PERFORMER TO ARTIST (1926–1932).

"Ol′ Man River" (1926–1928).

"The Power to Create Beauty" (1928–1929).

To Feed His Soul (1930).

Troubled Spirit (1930–1931).

Giver of Grace (1931–1932).

TRIBUNE OF A CULTURE (1933–1936).

Film and the Politics of Culture (1933–1934).

Test Run: London–Moscow–Hollywood (1934–1935).

White Film, Black Culture (1936).

TO BE A PROPHET (1936–1939).

Russia′s Sun: Stalin′s Shadow (1936–1937).

Spain′s Ramparts: "The Artist Must Elect" (1938).

A Home in That Rock (1938–1939).

Notes.

Index.

Recenzii

Biographies penned by the children of the famous and noteworthy are born suspect. Either they′re see–no–evil love letters like "My Father′s Daughter," Tina Sinatra′s memoir of her dad, Frank; or they are nasty memoirs of image immolation and score settling, such as Christina Crawford′s "Mommie Dearest" (just try watching Joan Crawford in "Mildred Pierce" without thinking about wire hangers).

In "The Undiscovered Paul Robeson," the first installment of a two–volume biography of his father, Paul Robeson Jr. deftly avoids crash landing in either camp. Stating that his father "despised sycophants," Robeson Jr. writes, "It would be an insult to his memory if I were to make the slightest attempt to satisfy those who crave a Robeson icon, those who wish to worship at a shrine, or those who are beguiled by his political persona."

Robeson Jr. is more concerned with rescuing his father from the strange obscurity that has clouded his legacy and refuting the stubborn myths that clung to the man in life and have yet to fade in the quarter–century since his death – namely, that Robeson was a card–carrying Communist (he wasn′t) who spent his later, blacklisted years as a bitter recluse (he didn′t).

Of course, had Robeson chosen to do so, who could have blamed him? A gifted singer and actor, he made his name on the stage and screen with heralded performances in "The Emperor Jones," "Othello," and "Show Boat," with his showstopping rendition of "Ol′ Man River." But Robeson was dogged by racism at every turn. Once considered "a credit to his race" – inspiring to blacks, unthreatening to whites – he was later deemed a traitor when he spoke out against racial intolerance and embraced various unpopular political causes. Years of government harassment, especially by the infamous House Un–American Activities Committee, eventually eroded both his career and health.

Because this volume concludes in 1939, Robeson Jr.′s focus is on his father as a young man and burgeoning artist, not as a persecuted activist. Born April 9, 1898, in Princeton, N.J., Robeson was the youngest of seven children. His father, William Drew Robeson, escaped slavery three years before the Civil War began. His mother, Maria Louisa Bustill, a member of one of Philadelphia′s prominent black families, died in a freakish fire when her son was 5.

A church pastor, William Robeson instilled in his children "the techniques of survival in a viciously racist climate," writes Robeson Jr. "He insisted that Paul must never appear to be challenging" white people. "Climb up if you can, but always show you are grateful," Robeson would tell his son."Above all, do nothing to give them cause to fear you."

Such advice did little to spare Robeson the sting of bigotry. He attended high school in a neighboring town because Princeton had no secondary school for black children. A fine student, Robeson received a scholarship to Rutgers University, where he was the third black student in the school′s then 150–year history. Both students and teachers were openly hostile, and when he tried out for the football team, several players threatened to strike. Robeson not only made the team but was twice selected as an All–American; still, he was benched for the homecoming game against a Southern college that refused to have its players on the same field with a black man.

In college, Robeson was also a member of the glee club. He′d been singing since childhood and had developed a resonant bass voice. But a career in the arts didn′t interest him initially; he wanted to be a lawyer. While attending Columbia Law School, he also appeared in amateur theatrical productions but kept his sights on practicing in a Wall Street law firm. After graduation he got a job in a New York firm, but his tenure was short–lived. White co–workers treated him with such contempt that, Robeson Jr. writes, "It was inconceivable to Paul that he would enter a profession in which his possibilities would be so limited by racial prejudice. He would risk casting his lot with the theater."

One of Robeson′s great champions was his wife, Eslanda "Essie" Cardozo Goode, who sacrificed her dreams of becoming a doctor to nurture her husband′s career. But it was a rocky marriage, shaken by Robeson′s infidelities, the demands of his profession, and constant travel. Still, seeing the world also broadened his political views, sparking his interest in Africa as well as the struggles of all oppressed peoples. In 1934 he made his first trip to Russia and was moved by kindness shown him by its people. "Here, for the first time in my life, I walk in full human dignity," Robeson said to one of his Soviet hosts. "You cannot imagine what that means to me as a Negro." Where Robeson once shunned politics, he now saw activism as an integral part of his art.

This is an accomplished and moving memoir. While his admiration and respect for his father is apparent, Robeson Jr. never bends double to sanctify him – nor does he need to. By simply telling his father′s story wholly and honestly, he restores the man to his rightful place as one of the most acclaimed people of the first half of the 20th century.

"Paul Robeson has nothing to fear from history, from the public, or any critic," his son writes. "His true image speaks for itself and needs no polishing or protection." (Boston Globe) He was a huge man, 6 feet 3 inches, 230 pounds, with the posture of a dancer and the massive chest and broad shoulders of an athlete. His voice, a warm, rich bass, could fill a room with a whisper. All his life, Paul Robeson elicited superlatives from those who came in contact with him. The theater critic George Jean Nathan, after watching him play the lead in "All God′s Chillun Got Wings," called Robeson "one of the most thoroughly eloquent, impressive actors that I have looked at and listened to in almost 20 years of professional theatergoing." "He has an extraordinary voice, but he knows how to use it so that the tones and phrases pour forth without effort," a British critic wrote in 1933. "His tone is always lyrical; it flows like a deep river which has not a ripple on its surface." "Paul fascinated everyone," Emma Goldman wrote in her memoirs. "Nothing I had been told about his singing adequately expressed the moving quality of his voice. Paul was also a lovable personality."

Robeson was born in Princeton, N.J., in 1898, the youngest of the five children of the Rev. William Drew Robeson, a former slave who had become a clergyman, and Maria Louisa Bustill Robeson, who died in a fire when Paul was 6. He attended Rutgers University –– only the third basketball teams, was a first–team All–American football player, a soloist in the glee club and a leader in the debating society. He won the class oratorical prize four years in a row, was elected to Phi Beta Kappa and the Cap and Skull honor society, was class valedictorian and gave the commencement address.

After Rutgers, Robeson went to Columbia Law School. After graduating in 1923, he took a job at a Wall Street law firm. When a stenographer informed him that she would not take dictation "from a nigger," and the partner who had recruited him suggested he open a law office in Harlem because white clients might not want to work with him, Robeson abandoned the law for a career as an actor and singer.

In 1928, Robeson, already an internationally acclaimed singer, actor and recording star, moved to London. He would spend the next 12 years in Europe, triumphing artistically and commercially in theater, film and on the concert stage. In the early 1930′s, Robeson began to identify himself with the African independence movement. He visited the Soviet Union in December 1934 at the invitation of the filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein, who wanted to work with him. According to his son, Paul Robeson Jr., in "The Undiscovered Paul Robeson,′′ he came away enormously impressed by the Soviet experiment and "profoundly affected by the climate of racial tolerance in the Soviet Union and by the sincere warmth expressed toward him by Russians in every walk of life." In 1936, he announced that he was sending Paul Jr. to school in the Soviet Union so that he could grow up in a society without racial prejudice.

From the mid–1930′s on, Robeson appeared regularly at rallies supporting anticolonialist and antifascist causes. In September 1939, fearful of war and convinced that he could speak out more freely and effectively in America than in England, Robeson returned to the United States with his wife and son. It is at this point that Paul Jr. ends the first volume of his biography.

There is no such thing as a definitive biography. For this reason alone, we must welcome Paul Robeson Jr.′s book. Still, we are obligated to ask him, as we would any biographer, what he has to add to the existing literature. In his preface, Paul Jr. tells us that he has written ′′an intimate, informal biography." I don′t quite know what informal means, but his biography is certainly not intimate. Nor can it be, as Paul Robeson Jr. saw very little of his father during the period covered in this first volume, which ends when he was 12 years old. While his father and mother lived in London, Paul Jr. was raised by his grandmother and attended school in Switzerland, the United States and the Soviet Union. Until the age of 7, he writes, his father was ′′a relative stranger...an intimidating presence." Thereafter, father and son lived in the same house for only brief periods until the family returned to the United States in 1939.

Paul Robeson Jr., a freelance journalist, translator and lecturer, claims that in his biography, he will reveal "pivotal aspects′′ of his father′s personality "that he kept mainly to himself." "My most important source," he tells us, "has been my father himself." But his father died 25 years ago, so unless Paul Jr. taped or made extensive notes of his conversations, he is asking us to rely on his memory of his father′s memories. Memory is a valuable source for the historian, but it is also dangerously unreliable.

Robeson Jr. never refers in his text or his notes to Martin Duberman′s well–received 1988 biography, or to the fact that he invited Duberman to write the biography and gave him full access to the family archives, only to criticize the book after it had been written. "The Undiscovered Paul Robeson" reads like Paul Jr.′s attempt to correct the story of his father′s life as told by Duberman. In the end, however, it adds little and omits a great deal from the earlier biography. Duberman′s sources are richer, his prose more vital, his understanding of the historical context far greater, his interpretations subtler and sounder.

The son′s most striking achievement is the narrative he provides of his parents′ tortured marriage. He reassures the reader that his parents loved each other, but he also recounts, in excruciating detail, his father′s many affairs and his callous disregard of his wife. If in his description of his parents′ marriage Paul Robeson Jr.′s account parallels that of Duberman, in his discussion of his father′s politics it diverges significantly. Paul Jr. de–emphasizes his father′s political sympathies with, and public support for, the Soviet Union. While he admits that his father never publicly criticized the Soviet Union, he maintains that privately his father "harbored grave doubts about internal Soviet politics." Regrettably, the only sources for this assertion, which flatly contradict the public record, are what Paul Jr. identifies in his notes as "conversations with my father."

It is difficult in the year 2001, knowing what we do about Soviet history, to understand why Paul Robeson–and others–supported Soviet political actions with such uncompromised vigor through the 1930′s. The task of the historian, however, is not to rewrite this past or to obfuscate it or make apologies for it, but to help us understand it. Paul Robeson Jr. has regrettably failed to do this in his new biography of his father. (The New York Times Book Review, April 8, 2001)

Paul Robeson, one of the world′s most famous actors from the 1920s through the 1950s and a man who led an extraordinary life by any measure, is not widely known today. In this moving and intimate memoir, his son, a freelance journalist and translator, blames his father′s current obscurity on the public response to his outspoken left–wing politics and insistence on racial pride, evident throughout his careers in college sports, on stage and as a spokesperson for equal rights. Most pointedly at issue, in Robeson Jr.′s eyes, is the far–reaching, vituperative media campaign waged during the McCarthy era that (wrongly) labeled Robeson a Communist and caused him to be blacklisted from 1949 until his death in 1976. Born in 1898 to a runaway slave who became a famed minister and preacher, in 1915 Robeson was the third African–American admitted to Rutgers University, where, despite overt racism, he became a noted scholar, athlete and orator. After graduating from Columbia Law School, he tried his hand at the theater and, in 1924, was heralded for his performance in O′Neill′s The Emperor Jones. Robeson went on to become an international star, notably playing Othello in London and appearing in the stage and film versions of the musical Show Boat. During this time, he also entered the political arena with his support of antifascist and leftist groups, later used by the press and anti–Communist witch–hunters to tarnish Robeson′s reputation. Robeson Jr. writes forcefully of his parents′ successes–his mother, Eslanda, led a life as public as her husband′s–as well as of their troubled marriage. This version of his father′s life is an important, well–wrought addition to African–American, cold War and theater scholarship. (Publishers Weekly)

Robeson Jr. (Paul Robeson, Jr., Speaks to America, 1993) traces his father′s life from birth through the start of WWII, when the performer and activist all but fell mute. The author′s ranging voice can be defensive, proud, protective, and bell–clear, and while he may not have the thunderous delivery of his father, his words come across as heartfelt. The focus of his study is on the development of his father′s cultural and political views, while considerable attention is paid to the nature of Robeson′s relationship with his wife. Clearly, much of Robeson′s sense of dignity, self–worth, and justice came as a result of growing up the son of a clergyman (his father was pastor of Harlem′s Zion Church)–and from his own harsh experiences as the only black student at Rutgers. His drive to excel as a performer is set within the larger context of his conviction that the African–American cultural and spiritual experience was central to their liberation as a people. But this can hardly be considered late–breaking news–nor, as the author suggests, is the "debunking" of Robeson as a Communist likely to surprise many. While it is undeniable that Robeson admired the Soviet Union for its racial tolerance, as well as its anticolonial and antifascist stances, it now appears that he was more of a dupe than a true believer. Indeed, his silence on the Stalinist purges (to say nothing of the Scottsboro trials) would have made for some interesting speculation on Robeson Jr.′s part–and it is understandable, perhaps, but unfortunate all the same that such speculations never found their way into the author′s account. Robeson Jr. does, however, break some new ground in his discussion of his father′s artistic development, particularly regarding his use of the traditional folk style in spirituals.

Informed by a filial piety throughout, but hardly and unbiased take. (Kirkus Reviews)

"...this is a useful book..." (Black and Asian Studies Association Newsletter, April 2002)

"This is an accomplished and moving memoir...he (Robeson, Jr.) restores the man to his rightful place as one of the most acclaimed people of the first half of the 20th century." (Boston Globe) "This version of his father′s life is an important, well–wrought addition to African–American, Cold War and theater scholarship." (Publishers Weekly)

"The author′s ranging voice can be defensive, proud, protective, and bell–clear, and while he may not have the thunderous delivery of his father, his words come across as heartfelt." (Kirkus Reviews)

"...this is a useful book..." (Black and Asian Studies Association Newsletter, April 2002)

In "The Undiscovered Paul Robeson," the first installment of a two–volume biography of his father, Paul Robeson Jr. deftly avoids crash landing in either camp. Stating that his father "despised sycophants," Robeson Jr. writes, "It would be an insult to his memory if I were to make the slightest attempt to satisfy those who crave a Robeson icon, those who wish to worship at a shrine, or those who are beguiled by his political persona."

Robeson Jr. is more concerned with rescuing his father from the strange obscurity that has clouded his legacy and refuting the stubborn myths that clung to the man in life and have yet to fade in the quarter–century since his death – namely, that Robeson was a card–carrying Communist (he wasn′t) who spent his later, blacklisted years as a bitter recluse (he didn′t).

Of course, had Robeson chosen to do so, who could have blamed him? A gifted singer and actor, he made his name on the stage and screen with heralded performances in "The Emperor Jones," "Othello," and "Show Boat," with his showstopping rendition of "Ol′ Man River." But Robeson was dogged by racism at every turn. Once considered "a credit to his race" – inspiring to blacks, unthreatening to whites – he was later deemed a traitor when he spoke out against racial intolerance and embraced various unpopular political causes. Years of government harassment, especially by the infamous House Un–American Activities Committee, eventually eroded both his career and health.

Because this volume concludes in 1939, Robeson Jr.′s focus is on his father as a young man and burgeoning artist, not as a persecuted activist. Born April 9, 1898, in Princeton, N.J., Robeson was the youngest of seven children. His father, William Drew Robeson, escaped slavery three years before the Civil War began. His mother, Maria Louisa Bustill, a member of one of Philadelphia′s prominent black families, died in a freakish fire when her son was 5.

A church pastor, William Robeson instilled in his children "the techniques of survival in a viciously racist climate," writes Robeson Jr. "He insisted that Paul must never appear to be challenging" white people. "Climb up if you can, but always show you are grateful," Robeson would tell his son."Above all, do nothing to give them cause to fear you."

Such advice did little to spare Robeson the sting of bigotry. He attended high school in a neighboring town because Princeton had no secondary school for black children. A fine student, Robeson received a scholarship to Rutgers University, where he was the third black student in the school′s then 150–year history. Both students and teachers were openly hostile, and when he tried out for the football team, several players threatened to strike. Robeson not only made the team but was twice selected as an All–American; still, he was benched for the homecoming game against a Southern college that refused to have its players on the same field with a black man.

In college, Robeson was also a member of the glee club. He′d been singing since childhood and had developed a resonant bass voice. But a career in the arts didn′t interest him initially; he wanted to be a lawyer. While attending Columbia Law School, he also appeared in amateur theatrical productions but kept his sights on practicing in a Wall Street law firm. After graduation he got a job in a New York firm, but his tenure was short–lived. White co–workers treated him with such contempt that, Robeson Jr. writes, "It was inconceivable to Paul that he would enter a profession in which his possibilities would be so limited by racial prejudice. He would risk casting his lot with the theater."

One of Robeson′s great champions was his wife, Eslanda "Essie" Cardozo Goode, who sacrificed her dreams of becoming a doctor to nurture her husband′s career. But it was a rocky marriage, shaken by Robeson′s infidelities, the demands of his profession, and constant travel. Still, seeing the world also broadened his political views, sparking his interest in Africa as well as the struggles of all oppressed peoples. In 1934 he made his first trip to Russia and was moved by kindness shown him by its people. "Here, for the first time in my life, I walk in full human dignity," Robeson said to one of his Soviet hosts. "You cannot imagine what that means to me as a Negro." Where Robeson once shunned politics, he now saw activism as an integral part of his art.

This is an accomplished and moving memoir. While his admiration and respect for his father is apparent, Robeson Jr. never bends double to sanctify him – nor does he need to. By simply telling his father′s story wholly and honestly, he restores the man to his rightful place as one of the most acclaimed people of the first half of the 20th century.

"Paul Robeson has nothing to fear from history, from the public, or any critic," his son writes. "His true image speaks for itself and needs no polishing or protection." (Boston Globe) He was a huge man, 6 feet 3 inches, 230 pounds, with the posture of a dancer and the massive chest and broad shoulders of an athlete. His voice, a warm, rich bass, could fill a room with a whisper. All his life, Paul Robeson elicited superlatives from those who came in contact with him. The theater critic George Jean Nathan, after watching him play the lead in "All God′s Chillun Got Wings," called Robeson "one of the most thoroughly eloquent, impressive actors that I have looked at and listened to in almost 20 years of professional theatergoing." "He has an extraordinary voice, but he knows how to use it so that the tones and phrases pour forth without effort," a British critic wrote in 1933. "His tone is always lyrical; it flows like a deep river which has not a ripple on its surface." "Paul fascinated everyone," Emma Goldman wrote in her memoirs. "Nothing I had been told about his singing adequately expressed the moving quality of his voice. Paul was also a lovable personality."

Robeson was born in Princeton, N.J., in 1898, the youngest of the five children of the Rev. William Drew Robeson, a former slave who had become a clergyman, and Maria Louisa Bustill Robeson, who died in a fire when Paul was 6. He attended Rutgers University –– only the third basketball teams, was a first–team All–American football player, a soloist in the glee club and a leader in the debating society. He won the class oratorical prize four years in a row, was elected to Phi Beta Kappa and the Cap and Skull honor society, was class valedictorian and gave the commencement address.

After Rutgers, Robeson went to Columbia Law School. After graduating in 1923, he took a job at a Wall Street law firm. When a stenographer informed him that she would not take dictation "from a nigger," and the partner who had recruited him suggested he open a law office in Harlem because white clients might not want to work with him, Robeson abandoned the law for a career as an actor and singer.

In 1928, Robeson, already an internationally acclaimed singer, actor and recording star, moved to London. He would spend the next 12 years in Europe, triumphing artistically and commercially in theater, film and on the concert stage. In the early 1930′s, Robeson began to identify himself with the African independence movement. He visited the Soviet Union in December 1934 at the invitation of the filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein, who wanted to work with him. According to his son, Paul Robeson Jr., in "The Undiscovered Paul Robeson,′′ he came away enormously impressed by the Soviet experiment and "profoundly affected by the climate of racial tolerance in the Soviet Union and by the sincere warmth expressed toward him by Russians in every walk of life." In 1936, he announced that he was sending Paul Jr. to school in the Soviet Union so that he could grow up in a society without racial prejudice.

From the mid–1930′s on, Robeson appeared regularly at rallies supporting anticolonialist and antifascist causes. In September 1939, fearful of war and convinced that he could speak out more freely and effectively in America than in England, Robeson returned to the United States with his wife and son. It is at this point that Paul Jr. ends the first volume of his biography.

There is no such thing as a definitive biography. For this reason alone, we must welcome Paul Robeson Jr.′s book. Still, we are obligated to ask him, as we would any biographer, what he has to add to the existing literature. In his preface, Paul Jr. tells us that he has written ′′an intimate, informal biography." I don′t quite know what informal means, but his biography is certainly not intimate. Nor can it be, as Paul Robeson Jr. saw very little of his father during the period covered in this first volume, which ends when he was 12 years old. While his father and mother lived in London, Paul Jr. was raised by his grandmother and attended school in Switzerland, the United States and the Soviet Union. Until the age of 7, he writes, his father was ′′a relative stranger...an intimidating presence." Thereafter, father and son lived in the same house for only brief periods until the family returned to the United States in 1939.

Paul Robeson Jr., a freelance journalist, translator and lecturer, claims that in his biography, he will reveal "pivotal aspects′′ of his father′s personality "that he kept mainly to himself." "My most important source," he tells us, "has been my father himself." But his father died 25 years ago, so unless Paul Jr. taped or made extensive notes of his conversations, he is asking us to rely on his memory of his father′s memories. Memory is a valuable source for the historian, but it is also dangerously unreliable.

Robeson Jr. never refers in his text or his notes to Martin Duberman′s well–received 1988 biography, or to the fact that he invited Duberman to write the biography and gave him full access to the family archives, only to criticize the book after it had been written. "The Undiscovered Paul Robeson" reads like Paul Jr.′s attempt to correct the story of his father′s life as told by Duberman. In the end, however, it adds little and omits a great deal from the earlier biography. Duberman′s sources are richer, his prose more vital, his understanding of the historical context far greater, his interpretations subtler and sounder.

The son′s most striking achievement is the narrative he provides of his parents′ tortured marriage. He reassures the reader that his parents loved each other, but he also recounts, in excruciating detail, his father′s many affairs and his callous disregard of his wife. If in his description of his parents′ marriage Paul Robeson Jr.′s account parallels that of Duberman, in his discussion of his father′s politics it diverges significantly. Paul Jr. de–emphasizes his father′s political sympathies with, and public support for, the Soviet Union. While he admits that his father never publicly criticized the Soviet Union, he maintains that privately his father "harbored grave doubts about internal Soviet politics." Regrettably, the only sources for this assertion, which flatly contradict the public record, are what Paul Jr. identifies in his notes as "conversations with my father."

It is difficult in the year 2001, knowing what we do about Soviet history, to understand why Paul Robeson–and others–supported Soviet political actions with such uncompromised vigor through the 1930′s. The task of the historian, however, is not to rewrite this past or to obfuscate it or make apologies for it, but to help us understand it. Paul Robeson Jr. has regrettably failed to do this in his new biography of his father. (The New York Times Book Review, April 8, 2001)

Paul Robeson, one of the world′s most famous actors from the 1920s through the 1950s and a man who led an extraordinary life by any measure, is not widely known today. In this moving and intimate memoir, his son, a freelance journalist and translator, blames his father′s current obscurity on the public response to his outspoken left–wing politics and insistence on racial pride, evident throughout his careers in college sports, on stage and as a spokesperson for equal rights. Most pointedly at issue, in Robeson Jr.′s eyes, is the far–reaching, vituperative media campaign waged during the McCarthy era that (wrongly) labeled Robeson a Communist and caused him to be blacklisted from 1949 until his death in 1976. Born in 1898 to a runaway slave who became a famed minister and preacher, in 1915 Robeson was the third African–American admitted to Rutgers University, where, despite overt racism, he became a noted scholar, athlete and orator. After graduating from Columbia Law School, he tried his hand at the theater and, in 1924, was heralded for his performance in O′Neill′s The Emperor Jones. Robeson went on to become an international star, notably playing Othello in London and appearing in the stage and film versions of the musical Show Boat. During this time, he also entered the political arena with his support of antifascist and leftist groups, later used by the press and anti–Communist witch–hunters to tarnish Robeson′s reputation. Robeson Jr. writes forcefully of his parents′ successes–his mother, Eslanda, led a life as public as her husband′s–as well as of their troubled marriage. This version of his father′s life is an important, well–wrought addition to African–American, cold War and theater scholarship. (Publishers Weekly)

Robeson Jr. (Paul Robeson, Jr., Speaks to America, 1993) traces his father′s life from birth through the start of WWII, when the performer and activist all but fell mute. The author′s ranging voice can be defensive, proud, protective, and bell–clear, and while he may not have the thunderous delivery of his father, his words come across as heartfelt. The focus of his study is on the development of his father′s cultural and political views, while considerable attention is paid to the nature of Robeson′s relationship with his wife. Clearly, much of Robeson′s sense of dignity, self–worth, and justice came as a result of growing up the son of a clergyman (his father was pastor of Harlem′s Zion Church)–and from his own harsh experiences as the only black student at Rutgers. His drive to excel as a performer is set within the larger context of his conviction that the African–American cultural and spiritual experience was central to their liberation as a people. But this can hardly be considered late–breaking news–nor, as the author suggests, is the "debunking" of Robeson as a Communist likely to surprise many. While it is undeniable that Robeson admired the Soviet Union for its racial tolerance, as well as its anticolonial and antifascist stances, it now appears that he was more of a dupe than a true believer. Indeed, his silence on the Stalinist purges (to say nothing of the Scottsboro trials) would have made for some interesting speculation on Robeson Jr.′s part–and it is understandable, perhaps, but unfortunate all the same that such speculations never found their way into the author′s account. Robeson Jr. does, however, break some new ground in his discussion of his father′s artistic development, particularly regarding his use of the traditional folk style in spirituals.

Informed by a filial piety throughout, but hardly and unbiased take. (Kirkus Reviews)

"...this is a useful book..." (Black and Asian Studies Association Newsletter, April 2002)

"This is an accomplished and moving memoir...he (Robeson, Jr.) restores the man to his rightful place as one of the most acclaimed people of the first half of the 20th century." (Boston Globe) "This version of his father′s life is an important, well–wrought addition to African–American, Cold War and theater scholarship." (Publishers Weekly)

"The author′s ranging voice can be defensive, proud, protective, and bell–clear, and while he may not have the thunderous delivery of his father, his words come across as heartfelt." (Kirkus Reviews)

"...this is a useful book..." (Black and Asian Studies Association Newsletter, April 2002)

Notă biografică

PAUL ROBESON, Jr., is a freelance journalist, translator, and highly regarded lecturer on American and Russian history. He served as a personal aide to his father for over twenty years and has been a civil rights activist since the 1940s. He is the owner and archivist of the Paul Robeson and Eslanda Robeson Collection, which consists of over 50,000 items, including thousands of photographs and hundreds of audio recordings.

Descriere

One of the greatest scholar-athlete-performing artists in U.S. history, Paul Robeson was among the most compelling figures of the 20th century. Now his son, Paul Robeson Jr., traces the dramatic arc of his rise to fame, painting a definitive picture of Paul Robeson's formative years.

Premii

- Hurston/Wright LEGACY Award Nominee, 2002