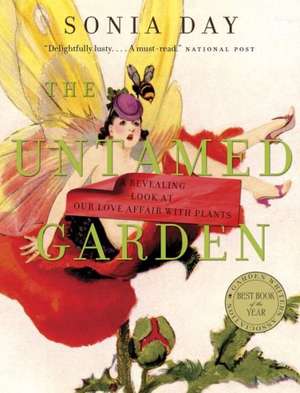

The Untamed Garden: A Revealing Look at Our Love Affair with Plants

Autor Sonia Dayen Limba Engleză Paperback – 4 noi 2013

Preț: 100.59 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 151

Preț estimativ în valută:

19.25€ • 20.10$ • 15.93£

19.25€ • 20.10$ • 15.93£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780771025068

ISBN-10: 0771025068

Pagini: 229

Ilustrații: COLOUR THROUGHOUT

Dimensiuni: 132 x 168 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.34 kg

Editura: McClelland & Stewart

ISBN-10: 0771025068

Pagini: 229

Ilustrații: COLOUR THROUGHOUT

Dimensiuni: 132 x 168 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.34 kg

Editura: McClelland & Stewart

Notă biografică

Master gardener SONIA DAY is the Toronto Star's gardening columnist and a well-respected gardening writer. She is the author of six previous books, including Tulips: Facts and Folklore About the World's Most Planted Flower, which won a Garden Globe Award of Achievement for writing from the U.S.-based Garden Writers Association, and, most recently, the Globe and Mail national bestseller Incredible Edibles: 43 Fun Things to Grow in the City. The Untamed Garden won the Garden Writers Association's Award of Best Book and the Gold Award for Best Overall Product of the Year. www.soniaday.com The author lives in Belwood, ON and Toronto, ON.

Extras

The Madonna Lily

The purest flower in the world

Ever wondered where the expression that a virgin has been “deflowered” comes from?

The answer lies in prudish attitudes to the facts of life, which persisted—amazingly—for thousands of years.

It may sound laughable today, but people actually once clung to the belief that plants were somehow different from the rest of us. That is, they didn’t have sex in order to reproduce themselves. Instead, the botanical world was a totally pure and innocent place, a sort of fantasy land, in fact. Thus a girl who lost her virginity was said to have been deflowered because she no longer possessed the sexless quality of a flower. Yes, pretty weird stuff. Yet plants were imbued with this strange ideal for a surprisingly long time—well into the twentieth century—and by a surprisingly diverse group of experts. Over the years, not one philosopher, doctor, botanist, or naturalist saw fit to challenge this belief—which seems odd, when you think about it. Although their lives were dedicated to the pursuit of science, these learned gents didn’t ever bother to ask themselves a couple of basic questions. One: if plants don’t have sex with each other, then how do they go about producing more plants? And two: what are their seeds for?

The flower that best sums up this cockeyed attitude to nature is the Madonna lily. Look closely at almost any early ecclesiastical art that features the Virgin Mary—there’s lots in churches and art galleries throughout Italy and Spain—and this lily, whose Latin name is Lilium candidum, is likely to be included somewhere. Early Christians regarded the flower as sacred because the pristine white petals symbolized Mary’s spotless body, while its clusters of golden stamens represented a soul gleaming with heavenly light. In one famous painting, called the Annunciation, which hangs in Florence’s Uffizi Gallery, master artist Leonardo da Vinci has even positioned a big spray of Madonna lilies smack next to the nose of an angel, who is shown in profile. And they are huge, these blooms. Suspended apparently in mid-air, they jump out at you. In choosing to depict the lilies so prominently, Leonardo clearly wanted us to notice their symbolism.

This painting shows the moment when the angel announces to Mary that she will give birth to the son of God—and his message is obvious. She is pure. But so is the white flower beside her.

Flowers Finally Get a Sex Life

Pity Monsieur M. Pouyanne. This belief in the purity of plants got him into deep trouble. He was a Frenchman toiling as a judge advocate in steamy Algeria at the beginning of the twentieth century. But his passion was the study of nature, and one day he noticed something extraordinary happening to an orchid in his collection, called Ophrys speculum. A wasp landed on it, clung to one of its petals, and performed some energetic jerky movements—an act that looked suspiciously as if the wasp was trying to mate with the flower. Then he noticed that the centre of this orchid looked remarkably like the female version of the same wasp. So in 1916, he wrote an article for the Journal of the National Horticultural Society of France suggesting that this activity indeed might be mating and that the orchid actually mimicked the appearance of the female wasp in order to “achieve some goal.”

Pouyanne’s prose was mild, the typical dry fodder of horticultural journals. Mindful of the prevailing attitudes of the day (and that, as an amateur naturalist, he wouldn’t be regarded as an expert), he did not go so far as to propose that the orchid was trying to trick the wasp into collecting pollen on its body so that when it flew away to another orchid, the grains would get carried along too and be transferred to the sexual apparatus of the second orchid, thereby helping pollination to take place. No, he was much more cautious than that. Even so, the French judge’s words provoked a firestorm. Dirty old man! howled the academic establishment. What a ridiculous suggestion, shrieked botanists. How could a learned journal print such rubbish, because plants don’t—repeat, don’t—have sexual organs. Even Charles Darwin, granddaddy of evolution, huffed that he “could not possibly conjecture” what the bee’s frantic jigging up and down on the orchid was all about.

Yet the critics couldn’t really be written off as silly, self-important fools. They were only doing what had been done for centuries. Over and over again. Ad nauseam. Long before Pouyanne’s controversial opinion piece, luminaries were getting their knuckles rapped for theorizing that plants required a sexual act to reproduce themselves. One expert who took a lot of heat in this regard was Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus. After studying stamens (which he concluded were the male part of the flower) and pistils (their female counterpart), he devised a new system of classifying plants according to the number and arrangement of their reproductive organs. In his manuscripts, Linnaeus also, in a very daring move, often attributed human attitudes and behaviour to plants’ sexual characteristics. One group he described, for instance, as “openly celebrating marriage in a way that is obvious to all” (in other words, their sexual organs were noticeably prominent in their flowers). In his mania to classify everything, Linnaeus even categorized his comely young wife, Sara, as his “monandrian lily”—because the flower signified virginity and “monandrian” meant “having only one man.”

But Linnaeus wasn’t taken seriously either. Although this eminently sensible botanist came up with a satisfactory system of naming and classifying plants that (despite a few quibbles) is still in use today, he went to his grave (at the age of seventy in 1778) worried sick about the “divine retaliation” that was in store for him. The reason? The critics called his theories about plant sex “obscene” and “offensive to public decency.”

The purest flower in the world

Ever wondered where the expression that a virgin has been “deflowered” comes from?

The answer lies in prudish attitudes to the facts of life, which persisted—amazingly—for thousands of years.

It may sound laughable today, but people actually once clung to the belief that plants were somehow different from the rest of us. That is, they didn’t have sex in order to reproduce themselves. Instead, the botanical world was a totally pure and innocent place, a sort of fantasy land, in fact. Thus a girl who lost her virginity was said to have been deflowered because she no longer possessed the sexless quality of a flower. Yes, pretty weird stuff. Yet plants were imbued with this strange ideal for a surprisingly long time—well into the twentieth century—and by a surprisingly diverse group of experts. Over the years, not one philosopher, doctor, botanist, or naturalist saw fit to challenge this belief—which seems odd, when you think about it. Although their lives were dedicated to the pursuit of science, these learned gents didn’t ever bother to ask themselves a couple of basic questions. One: if plants don’t have sex with each other, then how do they go about producing more plants? And two: what are their seeds for?

The flower that best sums up this cockeyed attitude to nature is the Madonna lily. Look closely at almost any early ecclesiastical art that features the Virgin Mary—there’s lots in churches and art galleries throughout Italy and Spain—and this lily, whose Latin name is Lilium candidum, is likely to be included somewhere. Early Christians regarded the flower as sacred because the pristine white petals symbolized Mary’s spotless body, while its clusters of golden stamens represented a soul gleaming with heavenly light. In one famous painting, called the Annunciation, which hangs in Florence’s Uffizi Gallery, master artist Leonardo da Vinci has even positioned a big spray of Madonna lilies smack next to the nose of an angel, who is shown in profile. And they are huge, these blooms. Suspended apparently in mid-air, they jump out at you. In choosing to depict the lilies so prominently, Leonardo clearly wanted us to notice their symbolism.

This painting shows the moment when the angel announces to Mary that she will give birth to the son of God—and his message is obvious. She is pure. But so is the white flower beside her.

Flowers Finally Get a Sex Life

Pity Monsieur M. Pouyanne. This belief in the purity of plants got him into deep trouble. He was a Frenchman toiling as a judge advocate in steamy Algeria at the beginning of the twentieth century. But his passion was the study of nature, and one day he noticed something extraordinary happening to an orchid in his collection, called Ophrys speculum. A wasp landed on it, clung to one of its petals, and performed some energetic jerky movements—an act that looked suspiciously as if the wasp was trying to mate with the flower. Then he noticed that the centre of this orchid looked remarkably like the female version of the same wasp. So in 1916, he wrote an article for the Journal of the National Horticultural Society of France suggesting that this activity indeed might be mating and that the orchid actually mimicked the appearance of the female wasp in order to “achieve some goal.”

Pouyanne’s prose was mild, the typical dry fodder of horticultural journals. Mindful of the prevailing attitudes of the day (and that, as an amateur naturalist, he wouldn’t be regarded as an expert), he did not go so far as to propose that the orchid was trying to trick the wasp into collecting pollen on its body so that when it flew away to another orchid, the grains would get carried along too and be transferred to the sexual apparatus of the second orchid, thereby helping pollination to take place. No, he was much more cautious than that. Even so, the French judge’s words provoked a firestorm. Dirty old man! howled the academic establishment. What a ridiculous suggestion, shrieked botanists. How could a learned journal print such rubbish, because plants don’t—repeat, don’t—have sexual organs. Even Charles Darwin, granddaddy of evolution, huffed that he “could not possibly conjecture” what the bee’s frantic jigging up and down on the orchid was all about.

Yet the critics couldn’t really be written off as silly, self-important fools. They were only doing what had been done for centuries. Over and over again. Ad nauseam. Long before Pouyanne’s controversial opinion piece, luminaries were getting their knuckles rapped for theorizing that plants required a sexual act to reproduce themselves. One expert who took a lot of heat in this regard was Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus. After studying stamens (which he concluded were the male part of the flower) and pistils (their female counterpart), he devised a new system of classifying plants according to the number and arrangement of their reproductive organs. In his manuscripts, Linnaeus also, in a very daring move, often attributed human attitudes and behaviour to plants’ sexual characteristics. One group he described, for instance, as “openly celebrating marriage in a way that is obvious to all” (in other words, their sexual organs were noticeably prominent in their flowers). In his mania to classify everything, Linnaeus even categorized his comely young wife, Sara, as his “monandrian lily”—because the flower signified virginity and “monandrian” meant “having only one man.”

But Linnaeus wasn’t taken seriously either. Although this eminently sensible botanist came up with a satisfactory system of naming and classifying plants that (despite a few quibbles) is still in use today, he went to his grave (at the age of seventy in 1778) worried sick about the “divine retaliation” that was in store for him. The reason? The critics called his theories about plant sex “obscene” and “offensive to public decency.”

Recenzii

Praise for The Untamed Garden

• "You don't have to be a gardener, expert or otherwise, to delight in The Untamed Garden. . . Fascinating and alluring. . . . Forget the chocolates and the wilted hothouse flowers. . . . Give this charming, fiery and joyous book of floral lore to your beloved instead." -- Halifax Chronicle Herald

• "Delightfully lusty. . . . A must-read." -- National Post

• "This is one of those rare crossovers that will appeal as much to gardeners as to those who prefer their nature more in the human line. . . . Day's lively, lusty prose gives us peep inside the botanical boudoir." -- Toronto Gardens

• "Beautifully printed and illustrated, making it perfect for the bedside table in anyone's boudoir. . . . It's an entertaining and informative read any time of year." -- Ottawa Citizen

• "You don't have to be a gardener, expert or otherwise, to delight in The Untamed Garden. . . Fascinating and alluring. . . . Forget the chocolates and the wilted hothouse flowers. . . . Give this charming, fiery and joyous book of floral lore to your beloved instead." -- Halifax Chronicle Herald

• "Delightfully lusty. . . . A must-read." -- National Post

• "This is one of those rare crossovers that will appeal as much to gardeners as to those who prefer their nature more in the human line. . . . Day's lively, lusty prose gives us peep inside the botanical boudoir." -- Toronto Gardens

• "Beautifully printed and illustrated, making it perfect for the bedside table in anyone's boudoir. . . . It's an entertaining and informative read any time of year." -- Ottawa Citizen