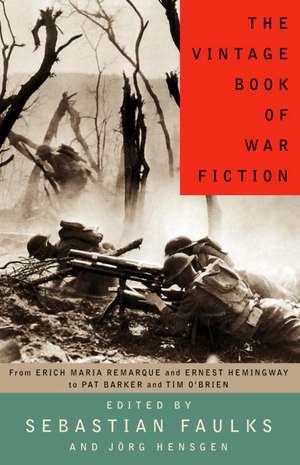

The Vintage Book of War Fiction

Editat de Sebastian Faulks, Jorg Hensgenen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 iul 2002

Many of the writers are concerned with battle, but others dwell on moments of calm, love, and friendship. From revolutionary Russia to Republican Spain; from the trenches of the Western Front to the skies over Korea and the jungles of Vietnam, this is a book filled with heroism and horror, savagery and compassion, and lightning-flashes of anarchic humor.

Preț: 134.84 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 202

Preț estimativ în valută:

25.81€ • 26.84$ • 21.30£

25.81€ • 26.84$ • 21.30£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 24 martie-07 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400030408

ISBN-10: 1400030404

Pagini: 416

Dimensiuni: 132 x 204 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Editura: Vintage Publishing

ISBN-10: 1400030404

Pagini: 416

Dimensiuni: 132 x 204 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Editura: Vintage Publishing

Notă biografică

Sebastian Faulks is best known for his trilogy of novels set in France: The Girl at the Lion d’Or, Birdsong, and Charlotte Gray, the latter two of which were bestsellers. After a period in France, he and his family now live in London.

Jörg Hensgen was born in Germany and studied at the universities of Wuppertal, Göttingen, and Hamburg. He now lives in London and works as an editor.

Jörg Hensgen was born in Germany and studied at the universities of Wuppertal, Göttingen, and Hamburg. He now lives in London and works as an editor.

Extras

Introduction

This is a book of extracts from works of fiction set in the wars of the twentieth century, and, when you come to think about it, the strangest thing about such books is that there are not more of them. Once the young literary form of the novel had decided, 250 years or so ago, that it would do more than tell stories, that it was uniquely suited by its access to inward psychological development and boundless narrative to explore ‘human nature’ and that that would be, for many writers and readers, its highest aim, then you would have thought that most ambitious novelists would have looked to see what conditions of existence offered them the most extreme and therefore, presumably, most rewarding circumstances for their study. War, surely, would have been the answer. If the writing of fiction had been undertaken not by writers but by scientists, they would certainly have seized on the dramatic potential of armed conflict for their experiments. These, they would have argued, are the ideal laboratory conditions for this examination of humanity; only under these intense pressures, both on the battlefield and behind it, both in the generations that fought and in their children, would the transcendent or outer qualities of humankind become visible.

Artists, however, aren’t like that. Writers write what they can; they write books about the stories or people that have moved them, without analysing, necessarily, the effects their work will have on their readers. They certainly don’t view it as scientific enterprise in which the rewards are bestowed on those who work at the frontiers of knowledge. Perhaps they should, but they don’t; and the other deterrent fact about war as a subject or background for fiction is that it is so disgusting. Which writer would willingly immerse himself for two or three years in this drab world of units and numbers, of industrial metal and meaningless death, without women or children or costume or domestic drama or even interesting food and drink? Laboratory of souls maybe, they would reply, but what a repellent and austere one.

Well, there are ways round that problem; in fact there are more ways of disarming a reader’s natural disinclination to read about such things than of overcoming the writer’s reluctance to write about them. I remember the reactions of friends and colleagues who asked me what I was writing in the early 1990s when I told them it was a novel set in the First World War. They thought I was insane. No one (or no one they could think of) had written a novel in England about this war since . . . well, since Robert Graves—or perhaps that wasn’t a novel. Anyway, it would be impossible to improve on the great books of the 1920s; war was a subject for decrepit old men in Aldershot bungalows; and, outside the British Legion library, it would have no sale at all. Oddly enough when the novel, Birdsong, came out in 1993 and met with some success, many of the same people assured me it was because I had ‘jumped on a First World War bandwagon’.

It does seem that war has to some extent come back into play as a background or setting for serious fiction, though writers today are unlikely to follow the direct course to the Front of Erich Maria Remarque or even the twisting paths of Evelyn Waugh, whose Sword of Honour trilogy fully digested a personal experience of combat before setting it in a social context. They will look for different angles. The fall-out, the repercussions, the social eddies that begin from the hideous collisions of metal and flesh; the historical, post-Freudian, even the comic or ironic dimensions: these are likely to be of interest to modern writers, at the end of an old century and the start of a new millennium. How did we get here? Has ever there been such a century for killing as the one we have just endured? What did it mean? Have we really thought it through?

Pat Barker, Sebastien Japrisot, William Boyd, Louis de Bernières and others have recently used war for their own fictional ends; it serves a purpose in a wider artistic scheme. But one of the first things that will strike readers of this anthology is the high proportion of novelists who are drawing on their own experiences, recycled or recrafted to varying degrees, and the low proportion who have gone in with the pure, disinterested eye of fiction. Many writers have used the form of the novel as little more than a convenience for what is at heart a documentary account of what happened to them. We have tried, on the whole, to favour full-blown fiction over lightly fictionalised autobiography, though there were instances of fact-based fiction where the writing itself was so compelling (Sassoon, Tim O’Brien), so successfully transformed (Hemingway, Norman Mailer) or else dealt with an experience or a conflict that would otherwise have been unrepresented (Malraux) that we were glad not to be inflexible.

There seems little doubt that the main impulse of a writer such as A.D. Gristwood was a documentary one. He wanted to get down on paper what the Great War was like, and if that meant inventing a perfunctory story and changing a few names, so be it. Later generations have been thankful for what he did, and such purpose can give real power to the writing, as it did to the overtly political novel Under Fire, which its author, Henri Barusse, hoped would help to stop the fighting. Witnessing what no human being had ever seen before, however—slaughter of ten million men for no apparent reason—proved an experience difficult to transmute into fiction, and there are not many outstanding novels to emerge from 1914–18. Exceptions include books by Henry Williamson, Frederic Manning, R.H. Mottram and Richard Aldington; unfortunately, Ford Madox Ford’s Tietjens tetralogy, the most highly esteemed of all, defeated our attempts to find an extract that was both representative and self-contained.

In compiling this anthology we were aware of the attraction of good writing for its own sake but also of the need to be to some extent representative—to vary the contents by nationality of author, by conflict, by type of combat (by air and sea as well as by land), but above it all by tone. There is no shortage of novels that describe bullet wounds and bombardments; there are not so many that talk about what was going on elsewhere. For this reason we were particularly pleased to include extracts from Elizabeth Bowen, Jean-Louis Curtis and John Horne Burns. Where it seemed possible, we looked to include humorous writing (Louis de Bernières, Laurie Lee, Christopher John Farley), or incidents that illuminated peripheral or contingent aspects of war—Wolfgang Koeppen’s Nazi on the loose in Rome, for instance, Stratis Myrivilis’s unashamed description of the beauty of firepower or Kurt Vonnegut’s wry account of literary profiteering.

With Vonnegut and Joseph Heller, we have cheated. We wanted to include them both out of admiration for their writing and because the theatres of war they wrote about (Dresden and the US airforce in the Mediterranean, respectively) were intriguing. However, we feared to bore readers with writing that would be too familiar to them, so in these two instances (only) we have taken extracts from the writers’ accounts of their novels rather than from the novels themselves.

Traditionally, the art of the anthologist is one of compromise, of steering a course between the Scylla of overfamiliarity and the Charybdis of too many unknowns. It is something like that of the music promoter who will use his star attractions to ‘break’ new acts and who will also make sure that while the main act plays songs from their new album they also include their greatest hits. Our rule of thumb was that if the Rolling Stones were going to play, they should give it all they’ve got; and if your curiosity does not flare up at the sight of Hemingway’s name, I hope at least you won’t deny yourself the intense pleasure of re-reading the extract in question.

The novelists’ techniques evolved as the wars themselves become different, and to some extent the literary style was affected by the military circumstances. Many English novelists of the Great War were acting as auxiliary reporters: ‘Look,’ they were saying, ‘no one really told you before what it was like’—and their ambitions were essentially journalistic. Those who went artistically further found what they could do constrained by the static nature of trench warfare. It is not surprising that, not only surveying an unprecedented human holocaust but watching it from a hole in the ground for months on end, these men produced such introspective books.

The Second World War brought, superficially, a completely different set of problems and responses. The combatants were unillusioned from the start. They knew how gruesome war would be, they knew that they had been dropped into it by inept politicians, but in place of the innocent patroitism of their fathers they had a proper moral cause to fight for; or at the very least, they were defending their homes. This was an inter-continental war fought in the jungle, the desert, by sea and by air. There was much less problem here about getting word home of what was going on; the difficulty was more that there was so much happening on so many different fronts that many voices and their stories were in danger of going unheard. To novelists, however, this multiplicity was an advantage, and made this the easiest war to write about. In the 1950s Alistair MacLean chose the Atlantic Convoys, in the 1960s John Fowles the German occupation of a Greek island; as late as 1995 Robert Harris found secret dramas at Bletchley. The growth of air war, of radar and the improvement of communications made this, frankly, more exciting than the trenches; and all novelists from Allied countries could approach the subject with a certain moral ease denied to Heinrich Böll or Shusaku Endo.

Writing from Vietnam became different again. Like the First World War, this proved a difficult experience to digest, and it was some time before American film-makers, in particular, were able to approach the subject. The amount of information had increased and so had access to it, particularly by television camera; but the combat was contained, peculiar and morally doubtful: drafted young civilians fighting a guerrilla war from helicopter gunships with napalm in a country they had never heard of . . . this was not Normandy or Iwo Jima. American writers eventually seemed to agree on a strategy to deal with it, and it seems to have been by recourse to what you might call a rock’n’roll style. When you read American accounts of Vietnam, it is very hard not to hear in them the tones of Haight Ashbury, of Jerry Rubin and the Yippies and the entire fusion of high and popular culture that was taking place in America at the time. The results are both shocking and poignant. It was as though Wyoming and Georgia, so reluctantly transplanted to the undergrowth of Vietnam, decided on its return that from now on it would speak its own demotic; that if Washington had sent them there, from now now on Washington would hear about it in their way, in their language. The literary craft of Larry Heinemann and Philip Caputo is far subtler than that, of course; but there is something insistently democratic in the way these people wrote which is analogous to the low-key yet haunting inscriptions of the Vietnam Memorial itself.

Whereas in Europe, the idiom of the commanders (even of an SAS officer such as Sir Peter de la Billiere) has retained a wistful air, a tacit acknowledgement that war is a dreadful last resort, American military leaders from MacArthur onward have shown a much franker relish in the way they speak of their business. When General Norman Schwarzkopf declared of the Iraqi army in 1991 that he was going to ‘cut it off, then kill it’, he may have been making a reference to Hannibal’s action at Cannae, but his private soldiers ignorantly used the language of the video game, while the Nato commanders in the Kosovo conflict seemed to believe that war could actually be waged as at a games console, safe from harm, with only the enemy targets open to damage. It is possible to envisage on the ground in bombed Belgrade or mutilated Kosovo the dramatically complex circumstances that might give rise to fiction in due course, but you feel it would be certain to come from those countries and not from the ranks of the arm’s-length Nato air forces. Perhaps that is unfair. The story of a troubled pilot who has inadvertently bombed the refugees he is meant to help, attacked the liberation army who are his allies or destroyed the embassy of a non-engaged enemy country is not without potential.

As for the West’s most recent war, on what President Bush has called ‘the axis of terror,’ it seems likely that film-makers will be the first to respond. Most observers of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, were at once queasily struck by the way the television pictures evoked so many mindless Hollywood bang-fests, and it was easy to conjecture the morbid contribution made by such exploitative films to the minds of the terrorists, already confused by material envy, sexual frustration and shame at the institutional failure of their religion. Yet Hollywood is nothing if not thick-skinned, and that awful day will doubtless provide a backdrop for many movies over the next few years. As for the air and ground war in Afghanistan itself, it seems too remote and too specialized—not just professional soldiers, but specialized units within those forces—to have a wider human resonance. The SAS memoir is already an established and fast-selling genre in Britian, but it relies for its effect on a documentary thrill that follows the breaking of professional confidences. Does this mean that war novels are finished?

As serious fiction has moved further from plot and incident, the reader’s hunger for books that impose an artistic and comforting pattern on the random events of life is less often satisfied. War can still deal with big events, while violent accidents or sudden reversals are considered melodramatic in ordinary fiction. Only in a war novel can you respectably kill off your main character with a stray sniper’s bullet, yet such deaths are in some way emblematic, in extreme form, of the inexplicable randomness of life events as we experience them from day to day in peace. A parent who has lost a child in a car accident may find greater affinity with the narrative emergencies of people in a wartime novel than in one that deals with a married woman’s failed love affair or a sensitive young man’s sexual awakening.

It still seems to me strange, when I came to think of it, that there are not more war books.

The bulk of the hard work that has gone into this anthology has been done by my co-editor Jörg Hensgen; his reading, researching, editing and organising have been prodigious. While I am happy to accept the blame for any shortcomings, the credit for any strengths this book may have is more likely to be his. I confess that occasionally during our collaboration I salved my guilt at the inequity of our contributions by reflecting that I was the first male member of my family for more than 100 years who, when confronted by a German of the same generation, had at least not tried to kill him.

Sebastian Faulks

This is a book of extracts from works of fiction set in the wars of the twentieth century, and, when you come to think about it, the strangest thing about such books is that there are not more of them. Once the young literary form of the novel had decided, 250 years or so ago, that it would do more than tell stories, that it was uniquely suited by its access to inward psychological development and boundless narrative to explore ‘human nature’ and that that would be, for many writers and readers, its highest aim, then you would have thought that most ambitious novelists would have looked to see what conditions of existence offered them the most extreme and therefore, presumably, most rewarding circumstances for their study. War, surely, would have been the answer. If the writing of fiction had been undertaken not by writers but by scientists, they would certainly have seized on the dramatic potential of armed conflict for their experiments. These, they would have argued, are the ideal laboratory conditions for this examination of humanity; only under these intense pressures, both on the battlefield and behind it, both in the generations that fought and in their children, would the transcendent or outer qualities of humankind become visible.

Artists, however, aren’t like that. Writers write what they can; they write books about the stories or people that have moved them, without analysing, necessarily, the effects their work will have on their readers. They certainly don’t view it as scientific enterprise in which the rewards are bestowed on those who work at the frontiers of knowledge. Perhaps they should, but they don’t; and the other deterrent fact about war as a subject or background for fiction is that it is so disgusting. Which writer would willingly immerse himself for two or three years in this drab world of units and numbers, of industrial metal and meaningless death, without women or children or costume or domestic drama or even interesting food and drink? Laboratory of souls maybe, they would reply, but what a repellent and austere one.

Well, there are ways round that problem; in fact there are more ways of disarming a reader’s natural disinclination to read about such things than of overcoming the writer’s reluctance to write about them. I remember the reactions of friends and colleagues who asked me what I was writing in the early 1990s when I told them it was a novel set in the First World War. They thought I was insane. No one (or no one they could think of) had written a novel in England about this war since . . . well, since Robert Graves—or perhaps that wasn’t a novel. Anyway, it would be impossible to improve on the great books of the 1920s; war was a subject for decrepit old men in Aldershot bungalows; and, outside the British Legion library, it would have no sale at all. Oddly enough when the novel, Birdsong, came out in 1993 and met with some success, many of the same people assured me it was because I had ‘jumped on a First World War bandwagon’.

It does seem that war has to some extent come back into play as a background or setting for serious fiction, though writers today are unlikely to follow the direct course to the Front of Erich Maria Remarque or even the twisting paths of Evelyn Waugh, whose Sword of Honour trilogy fully digested a personal experience of combat before setting it in a social context. They will look for different angles. The fall-out, the repercussions, the social eddies that begin from the hideous collisions of metal and flesh; the historical, post-Freudian, even the comic or ironic dimensions: these are likely to be of interest to modern writers, at the end of an old century and the start of a new millennium. How did we get here? Has ever there been such a century for killing as the one we have just endured? What did it mean? Have we really thought it through?

Pat Barker, Sebastien Japrisot, William Boyd, Louis de Bernières and others have recently used war for their own fictional ends; it serves a purpose in a wider artistic scheme. But one of the first things that will strike readers of this anthology is the high proportion of novelists who are drawing on their own experiences, recycled or recrafted to varying degrees, and the low proportion who have gone in with the pure, disinterested eye of fiction. Many writers have used the form of the novel as little more than a convenience for what is at heart a documentary account of what happened to them. We have tried, on the whole, to favour full-blown fiction over lightly fictionalised autobiography, though there were instances of fact-based fiction where the writing itself was so compelling (Sassoon, Tim O’Brien), so successfully transformed (Hemingway, Norman Mailer) or else dealt with an experience or a conflict that would otherwise have been unrepresented (Malraux) that we were glad not to be inflexible.

There seems little doubt that the main impulse of a writer such as A.D. Gristwood was a documentary one. He wanted to get down on paper what the Great War was like, and if that meant inventing a perfunctory story and changing a few names, so be it. Later generations have been thankful for what he did, and such purpose can give real power to the writing, as it did to the overtly political novel Under Fire, which its author, Henri Barusse, hoped would help to stop the fighting. Witnessing what no human being had ever seen before, however—slaughter of ten million men for no apparent reason—proved an experience difficult to transmute into fiction, and there are not many outstanding novels to emerge from 1914–18. Exceptions include books by Henry Williamson, Frederic Manning, R.H. Mottram and Richard Aldington; unfortunately, Ford Madox Ford’s Tietjens tetralogy, the most highly esteemed of all, defeated our attempts to find an extract that was both representative and self-contained.

In compiling this anthology we were aware of the attraction of good writing for its own sake but also of the need to be to some extent representative—to vary the contents by nationality of author, by conflict, by type of combat (by air and sea as well as by land), but above it all by tone. There is no shortage of novels that describe bullet wounds and bombardments; there are not so many that talk about what was going on elsewhere. For this reason we were particularly pleased to include extracts from Elizabeth Bowen, Jean-Louis Curtis and John Horne Burns. Where it seemed possible, we looked to include humorous writing (Louis de Bernières, Laurie Lee, Christopher John Farley), or incidents that illuminated peripheral or contingent aspects of war—Wolfgang Koeppen’s Nazi on the loose in Rome, for instance, Stratis Myrivilis’s unashamed description of the beauty of firepower or Kurt Vonnegut’s wry account of literary profiteering.

With Vonnegut and Joseph Heller, we have cheated. We wanted to include them both out of admiration for their writing and because the theatres of war they wrote about (Dresden and the US airforce in the Mediterranean, respectively) were intriguing. However, we feared to bore readers with writing that would be too familiar to them, so in these two instances (only) we have taken extracts from the writers’ accounts of their novels rather than from the novels themselves.

Traditionally, the art of the anthologist is one of compromise, of steering a course between the Scylla of overfamiliarity and the Charybdis of too many unknowns. It is something like that of the music promoter who will use his star attractions to ‘break’ new acts and who will also make sure that while the main act plays songs from their new album they also include their greatest hits. Our rule of thumb was that if the Rolling Stones were going to play, they should give it all they’ve got; and if your curiosity does not flare up at the sight of Hemingway’s name, I hope at least you won’t deny yourself the intense pleasure of re-reading the extract in question.

The novelists’ techniques evolved as the wars themselves become different, and to some extent the literary style was affected by the military circumstances. Many English novelists of the Great War were acting as auxiliary reporters: ‘Look,’ they were saying, ‘no one really told you before what it was like’—and their ambitions were essentially journalistic. Those who went artistically further found what they could do constrained by the static nature of trench warfare. It is not surprising that, not only surveying an unprecedented human holocaust but watching it from a hole in the ground for months on end, these men produced such introspective books.

The Second World War brought, superficially, a completely different set of problems and responses. The combatants were unillusioned from the start. They knew how gruesome war would be, they knew that they had been dropped into it by inept politicians, but in place of the innocent patroitism of their fathers they had a proper moral cause to fight for; or at the very least, they were defending their homes. This was an inter-continental war fought in the jungle, the desert, by sea and by air. There was much less problem here about getting word home of what was going on; the difficulty was more that there was so much happening on so many different fronts that many voices and their stories were in danger of going unheard. To novelists, however, this multiplicity was an advantage, and made this the easiest war to write about. In the 1950s Alistair MacLean chose the Atlantic Convoys, in the 1960s John Fowles the German occupation of a Greek island; as late as 1995 Robert Harris found secret dramas at Bletchley. The growth of air war, of radar and the improvement of communications made this, frankly, more exciting than the trenches; and all novelists from Allied countries could approach the subject with a certain moral ease denied to Heinrich Böll or Shusaku Endo.

Writing from Vietnam became different again. Like the First World War, this proved a difficult experience to digest, and it was some time before American film-makers, in particular, were able to approach the subject. The amount of information had increased and so had access to it, particularly by television camera; but the combat was contained, peculiar and morally doubtful: drafted young civilians fighting a guerrilla war from helicopter gunships with napalm in a country they had never heard of . . . this was not Normandy or Iwo Jima. American writers eventually seemed to agree on a strategy to deal with it, and it seems to have been by recourse to what you might call a rock’n’roll style. When you read American accounts of Vietnam, it is very hard not to hear in them the tones of Haight Ashbury, of Jerry Rubin and the Yippies and the entire fusion of high and popular culture that was taking place in America at the time. The results are both shocking and poignant. It was as though Wyoming and Georgia, so reluctantly transplanted to the undergrowth of Vietnam, decided on its return that from now on it would speak its own demotic; that if Washington had sent them there, from now now on Washington would hear about it in their way, in their language. The literary craft of Larry Heinemann and Philip Caputo is far subtler than that, of course; but there is something insistently democratic in the way these people wrote which is analogous to the low-key yet haunting inscriptions of the Vietnam Memorial itself.

Whereas in Europe, the idiom of the commanders (even of an SAS officer such as Sir Peter de la Billiere) has retained a wistful air, a tacit acknowledgement that war is a dreadful last resort, American military leaders from MacArthur onward have shown a much franker relish in the way they speak of their business. When General Norman Schwarzkopf declared of the Iraqi army in 1991 that he was going to ‘cut it off, then kill it’, he may have been making a reference to Hannibal’s action at Cannae, but his private soldiers ignorantly used the language of the video game, while the Nato commanders in the Kosovo conflict seemed to believe that war could actually be waged as at a games console, safe from harm, with only the enemy targets open to damage. It is possible to envisage on the ground in bombed Belgrade or mutilated Kosovo the dramatically complex circumstances that might give rise to fiction in due course, but you feel it would be certain to come from those countries and not from the ranks of the arm’s-length Nato air forces. Perhaps that is unfair. The story of a troubled pilot who has inadvertently bombed the refugees he is meant to help, attacked the liberation army who are his allies or destroyed the embassy of a non-engaged enemy country is not without potential.

As for the West’s most recent war, on what President Bush has called ‘the axis of terror,’ it seems likely that film-makers will be the first to respond. Most observers of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, were at once queasily struck by the way the television pictures evoked so many mindless Hollywood bang-fests, and it was easy to conjecture the morbid contribution made by such exploitative films to the minds of the terrorists, already confused by material envy, sexual frustration and shame at the institutional failure of their religion. Yet Hollywood is nothing if not thick-skinned, and that awful day will doubtless provide a backdrop for many movies over the next few years. As for the air and ground war in Afghanistan itself, it seems too remote and too specialized—not just professional soldiers, but specialized units within those forces—to have a wider human resonance. The SAS memoir is already an established and fast-selling genre in Britian, but it relies for its effect on a documentary thrill that follows the breaking of professional confidences. Does this mean that war novels are finished?

As serious fiction has moved further from plot and incident, the reader’s hunger for books that impose an artistic and comforting pattern on the random events of life is less often satisfied. War can still deal with big events, while violent accidents or sudden reversals are considered melodramatic in ordinary fiction. Only in a war novel can you respectably kill off your main character with a stray sniper’s bullet, yet such deaths are in some way emblematic, in extreme form, of the inexplicable randomness of life events as we experience them from day to day in peace. A parent who has lost a child in a car accident may find greater affinity with the narrative emergencies of people in a wartime novel than in one that deals with a married woman’s failed love affair or a sensitive young man’s sexual awakening.

It still seems to me strange, when I came to think of it, that there are not more war books.

The bulk of the hard work that has gone into this anthology has been done by my co-editor Jörg Hensgen; his reading, researching, editing and organising have been prodigious. While I am happy to accept the blame for any shortcomings, the credit for any strengths this book may have is more likely to be his. I confess that occasionally during our collaboration I salved my guilt at the inequity of our contributions by reflecting that I was the first male member of my family for more than 100 years who, when confronted by a German of the same generation, had at least not tried to kill him.

Sebastian Faulks

Cuprins

Introduction

BRUCE CHATWIN Volunteers

LOUIS-FERDINAND CÉLINE Could I Be the Last Coward on Earth?

DAVID MALOUF Invisible Enemies

ERICH MARIA REMARQUE How Long It Takes For a Man to Die!

A.D. GRISTWOOD The Wasteland

STRATIS MYRIVILIS The Beauty of the Battlefield

ERNEST HEMINGWAY Going Back

WILLIAM BOYD Narrow Escapes

SIEGFRIED SASSOON My Own Little Show

PAT BARKER Finished with the War

SEBASTIEN JAPRISOT The Woman on Loan

ISAAC BABEL Treason

LAURIE LEE Thank God for the War

ANDRÉ MALRAUX Crash

HEINRICH BÖLL The Postcard

KAY BOYLE Defeat

JEAN-LOUIS CURTIS The Forests of the Night

ELIZABETH BOWEN Everybody in London Was in Love

ALISTAIR MACLEAN Fire on the Water

ROBERT HARRIS Enigma

LOUIS DE BERNIÈRES Send in the Clowns

JOHN FOWLES Freedom

NORMAN MAILER We You Coming-to-Get, Yank

JAMES JONES No Choice

SHUSAKU ENDO We Are About to Kill a Man

MARTIN BOOTH Hiroshima Joe

LOUIS BEGLEY Wartime Lies

ITALO CALVINO Why Are the Men Fighting?

JOSEPH HELLER They Were Trying to Kill Me

MICHAEL ONDAATJE The Last Medieval War

JOHN HORNE BURNS My Heart Finally Broke in Naples

WOLFGANG KOEPPEN A Servant of Death

KURT VONNEGUT A Nazi City Mourned at Some Profit

JAMES SALTER The Hunters

TIM O’BRIEN How to Tell a True War Story

PHILIP CAPUTO Be Like the Forest

LARRY HEINEMANN Paco’s Story

CHRISTOPHER J. KOCH Welcome to Saigon

BAO NINH The Jungle of Screaming Souls

CHRISTOPHER JOHN FARLEY My Favourite War

Biographical Notes

Select Bibliography

Acknowledgements

BRUCE CHATWIN Volunteers

LOUIS-FERDINAND CÉLINE Could I Be the Last Coward on Earth?

DAVID MALOUF Invisible Enemies

ERICH MARIA REMARQUE How Long It Takes For a Man to Die!

A.D. GRISTWOOD The Wasteland

STRATIS MYRIVILIS The Beauty of the Battlefield

ERNEST HEMINGWAY Going Back

WILLIAM BOYD Narrow Escapes

SIEGFRIED SASSOON My Own Little Show

PAT BARKER Finished with the War

SEBASTIEN JAPRISOT The Woman on Loan

ISAAC BABEL Treason

LAURIE LEE Thank God for the War

ANDRÉ MALRAUX Crash

HEINRICH BÖLL The Postcard

KAY BOYLE Defeat

JEAN-LOUIS CURTIS The Forests of the Night

ELIZABETH BOWEN Everybody in London Was in Love

ALISTAIR MACLEAN Fire on the Water

ROBERT HARRIS Enigma

LOUIS DE BERNIÈRES Send in the Clowns

JOHN FOWLES Freedom

NORMAN MAILER We You Coming-to-Get, Yank

JAMES JONES No Choice

SHUSAKU ENDO We Are About to Kill a Man

MARTIN BOOTH Hiroshima Joe

LOUIS BEGLEY Wartime Lies

ITALO CALVINO Why Are the Men Fighting?

JOSEPH HELLER They Were Trying to Kill Me

MICHAEL ONDAATJE The Last Medieval War

JOHN HORNE BURNS My Heart Finally Broke in Naples

WOLFGANG KOEPPEN A Servant of Death

KURT VONNEGUT A Nazi City Mourned at Some Profit

JAMES SALTER The Hunters

TIM O’BRIEN How to Tell a True War Story

PHILIP CAPUTO Be Like the Forest

LARRY HEINEMANN Paco’s Story

CHRISTOPHER J. KOCH Welcome to Saigon

BAO NINH The Jungle of Screaming Souls

CHRISTOPHER JOHN FARLEY My Favourite War

Biographical Notes

Select Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Descriere

The editors have assembled a powerful collection including some of the past century's finest writers--from Isaac Babel to Tim O'Brien--coming to terms with the dismal inheritance of war.