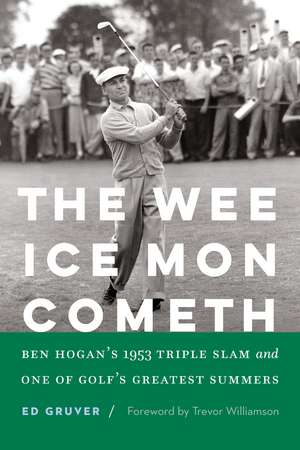

The Wee Ice Mon Cometh: Ben Hogan's 1953 Triple Slam and One of Golf's Greatest Summers

Autor Ed Gruver Cuvânt înainte de Trevor Williamsonen Limba Engleză Hardback – oct 2024

The Wee Ice Mon Cometh is the first book to detail Hogan’s historic accomplishment. His 1953 season remains the world’s greatest, and golfers seek to match his achievement every year. Bobby Jones in 1930 and Tiger Woods in 2000–2001 achieved comparable “slams,” but the Hogan Slam stands alone due to the car crash four years before that left Hogan on shattered legs. He nonetheless won with record-setting performances on three of the most challenging courses in the world: Augusta National at the Masters, the U.S. Open at Oakmont, and the British Open at Carnoustie, Scotland. Ed Gruver weaves together interviews with members of Hogan’s family, golf historians, playing partners, and business partners along with extensive research and eyewitness accounts of each tournament.

Seventy years after his historic feat, the Hogan Slam still serves as a symbol for the many comebacks Hogan had to make throughout his life—his father’s death by suicide when Ben was a boy, desperate days during the Great Depression, frustrating failures in tournaments early in his career, and the horrific accident that nearly killed him just as he was finally reaching the pinnacle of his profession.

Preț: 201.03 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 302

Preț estimativ în valută:

38.47€ • 41.77$ • 32.32£

38.47€ • 41.77$ • 32.32£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 02-16 aprilie

Livrare express 18-22 martie pentru 62.91 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781496238986

ISBN-10: 1496238982

Pagini: 232

Ilustrații: 14 photographs

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.5 kg

Editura: Nebraska

Colecția University of Nebraska Press

Locul publicării:United States

ISBN-10: 1496238982

Pagini: 232

Ilustrații: 14 photographs

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.5 kg

Editura: Nebraska

Colecția University of Nebraska Press

Locul publicării:United States

Notă biografică

Ed Gruver is an award-winning sportswriter, reporter, and author. His books include Bringing the Monster to Its Knees: Ben Hogan, Oakland Hills, and the 1951 U.S. Open and Hell with the Lid Off: Inside the Fierce Rivalry between the 1970s Oakland Raiders and Pittsburgh Steelers (Nebraska, 2019), among others. Trevor Williamson is the ambassador and keeper of the Carnoustie Way at the Carnoustie Golf Links in Scotland.

Extras

1

Augusta

The buds burst forth in brilliance every spring, azaleas and honeysuckles,

dogwoods and oaks, forsythia, tulips, and magnolias, more than 350 varieties

of plants and trees in all, providing a fragrant flowering of warm colors on

seventy acres of lush land in Augusta, Georgia.

The pageantry of color is further intensified by tradition. Caddies wear

white coveralls; winners don green jackets. Marshals and trash squads are

similarly dressed in standardized uniforms. The brown water in the hazards is

transformed into a more optically pleasing bright blue, courtesy of calcozine

dye. A sudden spring rain casts what Sports Illustrated once called “a mellow

patina” over brightly colored umbrellas hastily raised over the heads of fans

dampened by a downpour. Spectators, thousands strong, stand among the

purple frieze as players ponder putts amid pine-lined grounds.

Augusta is a spectacle of sport. It is a ritual; it is tradition. It is a former

indigo plantation being transformed in 1857 into a nursery by the new owner

of the land, Louis Berckmans, a baron of Belgian descent. A native of the

small town of Lierre, Louis was born in October of 1801 into a family of

proprietors and estate owners in Belgium. The Belgian Revolution in 1830–31

was contested over the Berckmans’ land, and in 1851 Louis and his family

came to the New World and took up residence in Plainfield, New Jersey.

Louis and his son Prosper began a nursery boasting wide varieties of

pears and additional fruit trees. The nobleman moved with his family to

Augusta in 1857, buying the 365-acre indigo plantation and converting it into

Fruitland Nurseries.

Emphasizing plant life, Louis and Prosper imported plants and trees from

other countries. Prosper is said to have favored the azaleas that populate

Augusta, with more than thirty varieties of the colorful, sweet-smelling

plant blooming in brilliant colors for two to three weeks between March and May.

When Bobby Jones arrived in Augusta seeking a plot of land upon which

to build the golfing champion’s dream course, he was stunned by the beauty

of the property. “Perfect!” Jones reportedly exclaimed upon his first viewing

of Fruitland Nurseries. This ground, he said, had been waiting years for

someone to place a golf course on it.

Augusta’s ground is historic, playing critical roles in the Revolutionary

War and Civil War. Inhabited in the early 1700s by Cherokee, Chickasaw,

Creek, and Yuchi Indians, it was used by Indigenous Americans as a place

to cross the Savannah River, named after the Savano Indians. Augusta’s first

English settlement came in 1736, with British general James Oglethorpe

naming the colony in honor of Princess Augusta, the wife of the Prince of

Wales, Frederick Louis.

Augusta would become known as the second city of Georgia, as it was

considered the second capital of the state. It served as the capital during the

Revolutionary War following the fall of Savannah to the British. Augusta

then fell to Lt. Col. Archibald Campbell in January 1779, but the British

withdrew not long after as American troops gathered on the shores of the

Savannah. Augusta again became the capital city of Georgia but fell again

to the British during the war.

The city of Augusta hosts the lone structure built and completed by the

Confederate States of America, the Confederate Powder Works. It entailed

twenty-six buildings along a two-mile stretch and produced 2.75 million

pounds of gunpowder, making Augusta the centerpiece of the Confederacy’s

production of firepower. The Augusta Canal, constructed in 1845, allowed

Augusta to become the second-biggest inland cotton market in the world.

Unlike its role in the Revolutionary War, Augusta was mostly unscarred by

battle in the Civil War. It served as a major rail center for Confederates, the

most notable being in September 1863 when the rebel troops of Lt. Gen. James

Longstreet traveled from Virginia to Chickamauga via Augusta. It became a

hospital center to accommodate mounting casualties, with funds for the sick

and wounded being raised by many of Augusta’s leading citizens, including

the Rev. Dr. Joseph R. Wilson, the father of future U.S. president Woodrow

Wilson.

On his historic March to the Sea late in 1864, Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh

Sherman bypassed Augusta. Despite Sherman’s assertion that he decided

not to attack Augusta due to the large concentration of Confederate troops

in the city, local folklore states that Sherman had been secretly ordered by

U.S. president Abraham Lincoln not to destroy Augusta because the First

Lady’s sister owned large stores of cotton in the city.

A century later Bobby Jones, a man called by essayist Herbert Warren

Wind the most favored son of the South since Robert E. Lee, made sports

history in 1930 by winning the Grand Slam of golf. Described by the Associated

Press as having a “short, stocky figure” and being golf ’s “Napoleon”

who strode over rolling battlegrounds, Jones nonetheless was a weary warrior

at the still-young age of twenty-eight. Having achieved a feat for the

ages, he retired from competitive golf. Jones’s announcement shocked

the sports world, but physically and mentally he had paid a price, dealing

with the pressure of high-level competition and the stress of being the favorite

in every tournament he played in. He longed to play the game in a more

relaxed atmosphere, to enjoy it with friends.

Jones met Clifford Roberts in the autumn of 1930, the young champion

having been invited by the middle-aged Wall Street investment banker to

view a tract of land they believed fit with Bobby’s plans to build a course

that reflected his love for the sport. Jones and Roberts proved as different

as two people could be. Jones was a southern gentleman, Roberts a native

midwesterner who had moved from Chicago to New York. Jones was sensitive,

Roberts relentless. Traveling from Atlanta to Augusta, Jones met with

Roberts, and Cliff drove Bobby down the double row of magnolias that led

to Fruitland Manor, which dated to the antebellum era. Fruitland Manor

would later be converted into the Augusta National Clubhouse.

Jones stood in front of the manor and viewed the vast expanse of land

before him. He said later he knew instantly it was the terrain he had always

hoped to find. He once told Sports Illustrated he was overwhelmed by the

“possibilities of the golf course that could be built in such a setting.”

The course would serve as the grounds for an annual tournament for

Jones and his friends, and as Bobby and Cliff shared the same passion

for a private club, they set about raising money. That they did this during

the Great Depression, a time when most golf courses were closing, made

for a great challenge.

Jones and Roberts paid $70,000 to purchase Fruitland Nurseries and

worked with the third generation of Berckmans associated with Augusta,

Prosper’s sons, Prosper Jr. and Louis Alphonse. It was Louis who advised

on the placement of the many trees and plants. Jones teamed with Scottish

architect Alister MacKenzie to create a course that Herbert Warren

Wind in 1955 called “very probably the most appealing inland course ever

built anywhere.”

The Augusta Chronicle on July 15, 1931, announced the news with the headline

“Bobby Jones to Build His Ideal Golf Course on Berckmans’ Place.”

Course construction took less than two years to complete, a remarkably

quick process aided no doubt by the fact that, as golf historian John Boyette

wrote in 2016, Jones and MacKenzie were two men of one mind when it

came to Augusta National. Jones chose MacKenzie over more famous course

architects, Donald Ross among them, and the history behind the friendship

between Jones and MacKenzie is somewhat shrouded.

“The mystery of how Bobby Jones and Alister MacKenzie first met—and

how Jones arrived at picking MacKenzie to design Augusta National Golf

Club—has never been fully explained,” Boyette wrote. The mystery involves

the Old and New Worlds, yet as Boyette notes, golf historians have never been

able to state definitively when the lives of these two legends first intersected.

Their initial encounter may have come at St. Andrews, the birthplace of

golf. Jones was a teenager when he first played St. Andrews’s Old Course in

the 1921 British Open, and it was in the early 1920s that MacKenzie, a civil

surgeon in the British Army and veteran of two wars, became a consultant

for St. Andrews, designing a system for the locations of flagsticks in championship

tournaments. Jones returned to the Old Course in 1926 for the Walker

Cup Matches, and Boyette states that this was when MacKenzie watched

Bobby play for the first time. MacKenzie next saw Jones three weeks later at

Royal Lytham & St. Annes, Bobby winning his first British Open. MacKenzie

and Jones were back at St. Andrews in 1927, Bobby shooting a record

285 and successfully defending his championship.

Augusta

The buds burst forth in brilliance every spring, azaleas and honeysuckles,

dogwoods and oaks, forsythia, tulips, and magnolias, more than 350 varieties

of plants and trees in all, providing a fragrant flowering of warm colors on

seventy acres of lush land in Augusta, Georgia.

The pageantry of color is further intensified by tradition. Caddies wear

white coveralls; winners don green jackets. Marshals and trash squads are

similarly dressed in standardized uniforms. The brown water in the hazards is

transformed into a more optically pleasing bright blue, courtesy of calcozine

dye. A sudden spring rain casts what Sports Illustrated once called “a mellow

patina” over brightly colored umbrellas hastily raised over the heads of fans

dampened by a downpour. Spectators, thousands strong, stand among the

purple frieze as players ponder putts amid pine-lined grounds.

Augusta is a spectacle of sport. It is a ritual; it is tradition. It is a former

indigo plantation being transformed in 1857 into a nursery by the new owner

of the land, Louis Berckmans, a baron of Belgian descent. A native of the

small town of Lierre, Louis was born in October of 1801 into a family of

proprietors and estate owners in Belgium. The Belgian Revolution in 1830–31

was contested over the Berckmans’ land, and in 1851 Louis and his family

came to the New World and took up residence in Plainfield, New Jersey.

Louis and his son Prosper began a nursery boasting wide varieties of

pears and additional fruit trees. The nobleman moved with his family to

Augusta in 1857, buying the 365-acre indigo plantation and converting it into

Fruitland Nurseries.

Emphasizing plant life, Louis and Prosper imported plants and trees from

other countries. Prosper is said to have favored the azaleas that populate

Augusta, with more than thirty varieties of the colorful, sweet-smelling

plant blooming in brilliant colors for two to three weeks between March and May.

When Bobby Jones arrived in Augusta seeking a plot of land upon which

to build the golfing champion’s dream course, he was stunned by the beauty

of the property. “Perfect!” Jones reportedly exclaimed upon his first viewing

of Fruitland Nurseries. This ground, he said, had been waiting years for

someone to place a golf course on it.

Augusta’s ground is historic, playing critical roles in the Revolutionary

War and Civil War. Inhabited in the early 1700s by Cherokee, Chickasaw,

Creek, and Yuchi Indians, it was used by Indigenous Americans as a place

to cross the Savannah River, named after the Savano Indians. Augusta’s first

English settlement came in 1736, with British general James Oglethorpe

naming the colony in honor of Princess Augusta, the wife of the Prince of

Wales, Frederick Louis.

Augusta would become known as the second city of Georgia, as it was

considered the second capital of the state. It served as the capital during the

Revolutionary War following the fall of Savannah to the British. Augusta

then fell to Lt. Col. Archibald Campbell in January 1779, but the British

withdrew not long after as American troops gathered on the shores of the

Savannah. Augusta again became the capital city of Georgia but fell again

to the British during the war.

The city of Augusta hosts the lone structure built and completed by the

Confederate States of America, the Confederate Powder Works. It entailed

twenty-six buildings along a two-mile stretch and produced 2.75 million

pounds of gunpowder, making Augusta the centerpiece of the Confederacy’s

production of firepower. The Augusta Canal, constructed in 1845, allowed

Augusta to become the second-biggest inland cotton market in the world.

Unlike its role in the Revolutionary War, Augusta was mostly unscarred by

battle in the Civil War. It served as a major rail center for Confederates, the

most notable being in September 1863 when the rebel troops of Lt. Gen. James

Longstreet traveled from Virginia to Chickamauga via Augusta. It became a

hospital center to accommodate mounting casualties, with funds for the sick

and wounded being raised by many of Augusta’s leading citizens, including

the Rev. Dr. Joseph R. Wilson, the father of future U.S. president Woodrow

Wilson.

On his historic March to the Sea late in 1864, Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh

Sherman bypassed Augusta. Despite Sherman’s assertion that he decided

not to attack Augusta due to the large concentration of Confederate troops

in the city, local folklore states that Sherman had been secretly ordered by

U.S. president Abraham Lincoln not to destroy Augusta because the First

Lady’s sister owned large stores of cotton in the city.

A century later Bobby Jones, a man called by essayist Herbert Warren

Wind the most favored son of the South since Robert E. Lee, made sports

history in 1930 by winning the Grand Slam of golf. Described by the Associated

Press as having a “short, stocky figure” and being golf ’s “Napoleon”

who strode over rolling battlegrounds, Jones nonetheless was a weary warrior

at the still-young age of twenty-eight. Having achieved a feat for the

ages, he retired from competitive golf. Jones’s announcement shocked

the sports world, but physically and mentally he had paid a price, dealing

with the pressure of high-level competition and the stress of being the favorite

in every tournament he played in. He longed to play the game in a more

relaxed atmosphere, to enjoy it with friends.

Jones met Clifford Roberts in the autumn of 1930, the young champion

having been invited by the middle-aged Wall Street investment banker to

view a tract of land they believed fit with Bobby’s plans to build a course

that reflected his love for the sport. Jones and Roberts proved as different

as two people could be. Jones was a southern gentleman, Roberts a native

midwesterner who had moved from Chicago to New York. Jones was sensitive,

Roberts relentless. Traveling from Atlanta to Augusta, Jones met with

Roberts, and Cliff drove Bobby down the double row of magnolias that led

to Fruitland Manor, which dated to the antebellum era. Fruitland Manor

would later be converted into the Augusta National Clubhouse.

Jones stood in front of the manor and viewed the vast expanse of land

before him. He said later he knew instantly it was the terrain he had always

hoped to find. He once told Sports Illustrated he was overwhelmed by the

“possibilities of the golf course that could be built in such a setting.”

The course would serve as the grounds for an annual tournament for

Jones and his friends, and as Bobby and Cliff shared the same passion

for a private club, they set about raising money. That they did this during

the Great Depression, a time when most golf courses were closing, made

for a great challenge.

Jones and Roberts paid $70,000 to purchase Fruitland Nurseries and

worked with the third generation of Berckmans associated with Augusta,

Prosper’s sons, Prosper Jr. and Louis Alphonse. It was Louis who advised

on the placement of the many trees and plants. Jones teamed with Scottish

architect Alister MacKenzie to create a course that Herbert Warren

Wind in 1955 called “very probably the most appealing inland course ever

built anywhere.”

The Augusta Chronicle on July 15, 1931, announced the news with the headline

“Bobby Jones to Build His Ideal Golf Course on Berckmans’ Place.”

Course construction took less than two years to complete, a remarkably

quick process aided no doubt by the fact that, as golf historian John Boyette

wrote in 2016, Jones and MacKenzie were two men of one mind when it

came to Augusta National. Jones chose MacKenzie over more famous course

architects, Donald Ross among them, and the history behind the friendship

between Jones and MacKenzie is somewhat shrouded.

“The mystery of how Bobby Jones and Alister MacKenzie first met—and

how Jones arrived at picking MacKenzie to design Augusta National Golf

Club—has never been fully explained,” Boyette wrote. The mystery involves

the Old and New Worlds, yet as Boyette notes, golf historians have never been

able to state definitively when the lives of these two legends first intersected.

Their initial encounter may have come at St. Andrews, the birthplace of

golf. Jones was a teenager when he first played St. Andrews’s Old Course in

the 1921 British Open, and it was in the early 1920s that MacKenzie, a civil

surgeon in the British Army and veteran of two wars, became a consultant

for St. Andrews, designing a system for the locations of flagsticks in championship

tournaments. Jones returned to the Old Course in 1926 for the Walker

Cup Matches, and Boyette states that this was when MacKenzie watched

Bobby play for the first time. MacKenzie next saw Jones three weeks later at

Royal Lytham & St. Annes, Bobby winning his first British Open. MacKenzie

and Jones were back at St. Andrews in 1927, Bobby shooting a record

285 and successfully defending his championship.

Cuprins

Foreword

Prologue: A Great Champion Meets Defeat

1: Augusta

2: Georgia on Their Minds

3: ‘Best Golf of My Life’

4: Oakmont

5: Abandon All Hope

6: Hades of Hulton

7: Carnoustie

8: ‘A Beastly Test’

9: Wee Ice Mon Cometh

10: Canyon of Heroes

Epilogue: Grandest Slam: Jones vs. Hogan vs. Tiger

Prologue: A Great Champion Meets Defeat

1: Augusta

2: Georgia on Their Minds

3: ‘Best Golf of My Life’

4: Oakmont

5: Abandon All Hope

6: Hades of Hulton

7: Carnoustie

8: ‘A Beastly Test’

9: Wee Ice Mon Cometh

10: Canyon of Heroes

Epilogue: Grandest Slam: Jones vs. Hogan vs. Tiger

Recenzii

"The descriptions of Hogan's shots, his demeanor on the course and even the agony of his competitors was all captured in a manner that puts the reader right in the gallery. Because of these sections, I genuinely enjoyed the book and would recommend it for any golf fan or historian."—Guy Who Reviews Sports Books

"The Wee Ice Mon Cometh accurately portrays an important but often overlooked athletic accomplishment in magnificent fashion. It is a wonderful addition to any sports library."—Stuart Shiffman, Book Reporter

“Ed Gruver picked a great subject to explore with Ben Hogan’s ‘Triple Crown’ season of 1953. Not only did Hogan win three majors that year; he dominated professional golf like few had done before—or since. The Wee Ice Mon Cometh tells the story of Hogan’s accomplishments in magnificent fashion.”—John Boyette, golf historian, executive editor of the Aiken Standard, and former sports editor of the Augusta Chronicle

“After his terrible car accident in 1949, Ben Hogan was told he might never walk again, much less ever play golf again. He proceeded to win six of his nine majors over the next four years. He proved them wrong. This book details the greatest year (1953) Mr. Hogan ever had playing golf, in which he won five of the six tournaments he entered along with all three majors he entered that year. It was arguably the greatest year in the history of the game.”—Robert Stennett, CEO of the Ben Hogan Foundation

“As soon as Uncle Ben could walk again, he got back to work and rediscovered greatness in the dirt. Even those who have never hit a golf shot can find inspiration in Hogan’s perseverance, grit, and determination in putting together the greatest year in golf.”—Lisa Scott, grandniece of Ben Hogan

“Ben Hogan’s ‘Triple Crown’ year is among the best of all time, highlighted by the fact that two of the wins came at arguably two of the toughest courses in the world—Oakmont and Carnoustie. His triumph at Oakmont was nothing short of classic Hogan—very methodical. Ed Gruver’s book finally brings Hogan’s season to light for all golf history lovers.”—David Moore, curator of collections at Oakmont Country Club

Descriere

A look back at golfer Ben Hogan’s historic 1953 season, still the closest any player has gotten to winning golf’s Grand Slam.