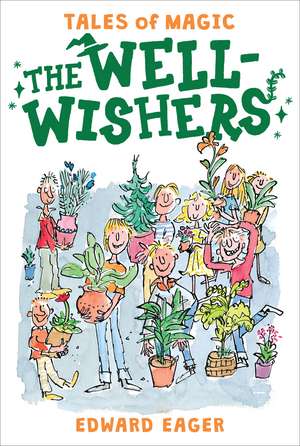

The Well-Wishers: Tales of Magic, cartea 6

Autor Edward Eager Ilustrat de N. M. Bodeckeren Limba Engleză Paperback – 29 aug 2016 – vârsta de la 8 până la 12 ani

Quentin Blake's charming art gets an updated look in this new edition of Edward Eager's beloved classic, featuring the original interior illustrations by N. M. Bodecker.

Preț: 48.66 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 73

Preț estimativ în valută:

9.31€ • 9.69$ • 7.69£

9.31€ • 9.69$ • 7.69£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 25 martie-08 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780544671676

ISBN-10: 0544671678

Pagini: 240

Ilustrații: Black-and-white illustrations

Dimensiuni: 130 x 194 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.18 kg

Editura: HMH Books

Colecția Hmh Books for Young Readers

Seria Tales of Magic

Locul publicării:United States

ISBN-10: 0544671678

Pagini: 240

Ilustrații: Black-and-white illustrations

Dimensiuni: 130 x 194 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.18 kg

Editura: HMH Books

Colecția Hmh Books for Young Readers

Seria Tales of Magic

Locul publicării:United States

Extras

1

James Begins

I know people who saythey can read any kind of book except an “I” book, and sometimes I think I agree with them. When I say “I” books, I mean the kind where somebody tells the story, and it starts out, “Little did I think when I first saw the red house how large it would loom in my life.” And later on, the person sees a sinister stranger digging a grave in the garden and he says, “If I had only remembered to telephone the police next morning, seven murders might have been averted.”

Laura and I often run into books like that, and Laura always says she holds the people who tell those stories in utter contempt, which is her way of saying they give her a pain. If we saw a sinister stranger digging a grave in our garden, we would remember to telephone the police, all right. And when we first sawourred house, weknewhow large it would loom.

Laura is my sister, and not bad as sisters go. Sometimes she has quite sound ideas.

One of her ideas was that we should tell the story this way, “I” book or not. Because the things that happened that winter happened to six of us (not counting parents), and the way they happened was different for each person. The way we felt about it was different for each person, too. So it is only right that each one should tell his part.

Laura says I should begin the whole thing because I have a well-organized mind. I am not boasting. That about my mind is what Mrs. Van Nest said one day. Mrs. Van Nest is our teacher, and sometimes her ideas are quite sound, too. She lets us do book reports on any book we like, and it doesn’t have to be on the list.

So I am beginning this story, and after that each one will tell what happened to him or her, as the case may be, and each one will tell it in his own way. Only we have made one rule, which is not to tell about the days when nothing happened, because who would want to read about them? And another rule is not to put in things that don’t mean anything and are just there to try to make it more exciting. Like saying, “There I stood, my heart beating.” Naturally your heart would be beating. Otherwise you wouldn’t be standing there; you’d be lying down dead.

But we are going to stick to the facts.

The first important fact about me is that my name is James Alexander Martin and I am in grade six-one-A, Mrs. Van Nest’s homeroom. Kip and Laura and Lydia are all in my class, too, but Gordy is in six-one-B and has to have Miss Wilson. Wow, do I pity him!

We try to be specially kind to Gordy, for that and other reasons, but sometimes we forget. Gordy is not a person who makes it easy for other people always to remember. Sometimes we have to be firm with him for his own good, but we try never to stoop to physical violence. Physical violence never solved anything in the world, we all realize. But sometimes with Gordy we forget that, too, or at least Kip and I do. Girls are soft.

If you wonder why Laura and I are in the same class in school, it is because we are the same age, being twins. But we do not look alike, or think alike, either, particularly about the magic, only that comes later.

As for my other sister Deborah, she is a mere babe, just starting the first grade, and by rights she shouldn’t come into this story at all. But rights have never meant a great deal to Deborah.

The story I’m talking about began one day in fall.

Of course it really began long before that, way back at the beginning of the summer, when Laura and I and our family first moved into the red house on Silvermine Road. Before that we lived in New York City.

The red house has a well in the garden, and the day we moved in a girl called Lydia Green, who lives in a funny big old place up the road, told us that it was a wishing well. Of course I knew better than to believe that. But Laura would believe anything, or try to.

Still, some very strange things did happen that summer. A lot of quite good wishes came true and some pretty keen good turns got done. That was the way the well was supposed to work. Selfish wishes didn’t mean a thing to it.

We got our heart’s desire in the end, too, just like in that bookThe Wonderful Gardenby E. Nesbit that Laura is so crazy about. It is not a bad book, by the way. A boy runs away and so does a tiger, and a portrait comes to life. The ending is nifty, if you’re young enough to believe in magic.

I’m not sure whether I am young enough or not. Mostly I think not. Magic doesn’t seem at all like the kind of thing thatwouldbe true, when you come to think of it. Still, neither do airplanes and electric lights and outer space, when you come to think ofthem.And it’s hard to explain the things that happened that summer any other way. Or the things that have been happening since, either. Of course it may all be a coincidence, the way Kip keeps saying.

Kip is a boy called Christopher, only he never is. Never is called that, I mean. He lives on our road, too, across from Lydia. He is a good kid, and just about my best friend, I guess.

He and Lydia and Laura and I were in on the magic (if that’s what it was) from the beginning. Gordy didn’t come into it till later in the summer. We didn’taskhim in exactly, but once he was there, we didn’t mind. Sometimes his ideas are every bit as sound as ours. All he needs is to be curbed once in a while, and shoved back on the right road. He is the victim of an unfortunate environment. His mother is rich. His full name is Gordon T. Witherspoon III.

When we first made the wish about our heart’s desire, we weren’t quite sure what our heart’s desire was, but when we got it, we knew. What it turned out to be was a little old house in the woods, all our own, to have for our secret clubhouse. How we found the house in the first place, and what we found in it, and exactly how it got to be ours is another story, and if you want to read that story, you will have to get a book calledMagic or Not?that tells all about it. But we did not write that book ourselves; so it does not have all our thoughts in it, the way this book will.

The part about the heart’s desire came right at the end of the summer, and after that the magic (if itwasmagic) seemed to be played out. At least we made quite a few perfectly good wishes on the well and they never came true, no matter how noble. That was all right with me, if that was how the well wanted things to end. But the girls said it was probably just resting and would start up again one day when we least expected it. You never can tell with magic. Or not, as the case may be.

And then suddenly it was fall, and for Laura and me there was a new school to get used to, and learning a new teacher’s ways and how to circumscribe them, if that is the word I mean, and that took up all our thoughts, for a while.

Football season began, too; so Kip and I were mainly too busy to bother with girls. I play end, but not very often, being light though rangy. Baseball is my game.

Laura and Lydia do not understand the true importance of football, or baseball either, but that is their female folly. As you grow older, the sexes grow farther and farther apart, I find. It is all part of maturing.

Still, the old group did find time to meet now and then in the house in the woods and have secret conclaves, though there wasn’t very much to conclavefor,now that the magic was a thing of the past.

Maybe that’s how we got into the habit of leaving Gordy out; so we’d have something to be secret about. We even had a mysterious secret sign. When it seemed like a good day for a meeting, one of us would hold up one finger, or two, along toward the end of last period. One if all five, two if without Gordy. Lately it was getting to be two most of the time.

Sometimes Gordy would come into the woods looking for us, but when he found us in the secret clubhouse without him, he never seemed to bear any grudge. That is one of the good things about Gordy.

We were always sorry afterward when this happened, and the fact that Gordy didn’t seem to get hurt or mad at us made us feel sorrier. You would think that would make us be nicer to him from then on, but it didn’t. The sorrier we felt each time, the more we went on leaving him out the next. That is the way people are. I do not think this is right, but it is true all the same. Though unfortunate.

This particular day Kip had held up two fingers just as the last bell rang, and we had all nodded, and when we marched out, everybody but Lydia got away quick without being spotted by the enemy. And Lydia crossed her fingers and told Gordy she had to go to the dentist. Which was not a lie really, because shedidhave to go. Only not that day.

So now there we all were (except you know whom) sitting on the front stoop of the secret house, because it was getting to be late September and the rooms inside were cold. But in front, the woods have been cut away to let the sun through.

Lydia had a pencil in her hand and a sketchbook in her lap, the way she does all the time now that she knows she has talent. It is wonderful how learning that she has talent has changed that girl. Maybe learning to make friends has had something to do with it, too. When we first met her, she was plain ornery, always doing crazy things just to be different, and quarreling with everybody. She is still ornery once in a while, and she and I still argue some. But she is a good kid, for a girl.

Today she was amusing us by doing caricatures of each one. The ones she did of Laura and Kip were awfully funny, but she didn’t get me right at all. My chin doesn’t stick out like that, at least not that far.

When we’d finished arguing about my chin, she started a portrait of herself, all long tangled blond hair with a scowl peeking through. Then she made a face at it and tore it up. “If you ask me,” she said, “it’s time something started happening around here. I’m used to school again. The sameness has set in.”

“Halloween next month,” Kip reminded her. “There’s the party in the gym.”

“Bobbing for apples!” Lydia was scornful. “And that old decoration committee. Black crepe paper cats on the walls; you’d think they could at least think up something original. Why didn’t they putmeon it;I’dfreeze their marrow for them!” And she drew a truly horrendous witch on the next page of her sketch pad.

“If you askme,” said Laura, “I think the trouble with us is we miss the magic.”

Everybody groaned, because we were all secretly trying not to think about that. But Laura is a great one for bringing hidden thoughts out into the open.

“We said this was going to be our secret witches’ den where we’d have midnight meetings and plan our secret spells,” she went on now. “We were going to do good turns to the whole town. But not a single magic thing’s happened, and pretty soon it’ll be too cold to come here anymore.”

“It’ll be warm again in the spring,” I said. “Maybe the magic goes to sleep in the winter, like woodchucks.”

“In books it’s almost always summer when the magic starts working,” put in Kip. “It’s almost always summer vacation.”

“So we won’t be distracted from our lessons, I suppose,” said Lydia bitterly. “As if being distracted weren’t just what we need!”

“Has anybody said anything to the well lately?” I wondered. “Maybe it’s just sitting there waiting for a friendly word.” After all, if we were going to believe in the magic (and everyone was talking suddenly as if we were), we might as well be efficient about it.

“No, and I don’t think we ought to,” said Laura. “I think we’re supposed to wait, no matter how long it takes.”

“Then let’s not talk about it,” I said. Because there is nothing so maddening as talking about something when you can’t do a single thing about it.

“I think weoughtto talk,” said Laura. “I think we’ve been silent about it, and each going his own way, long enough.” She turned to Lydia. “You didn’t say a thing when James asked if anybody’d been talking to the well lately, and neither did Kip. Have you been wishing on the sly?”

“I did think of giving it a look and a few words the other day,” Lydia admitted. “Just sort of generally about getting a move on. But I thought better of it.”

“I almost asked it to help with my history test,” said Kip. “And that would have been unselfish, because think how my parents would feel if I flunked. I didn’t do it, though. Maybe I should have. I only got a seventy-one.”

“No,” said Laura. “I think it’s a good thing you didn’t. I think if we start pestering it, it might get cross and take longer waking up than it would have, even. Or go all wrong when it does. I think we ought to swear a secret oath in blood not to gonearthe well until we’re absolutely sure it’s time.”

Everybody was willing, probably because even merely swearing a secret oath issortof a secret adventure. Kip had his scout knife handy, pricks were made, and the fatal oath duly sworn.

“There,” said Laura, sucking a finger. “That’s settled. Now when the well’s ready, it’ll tell us so. There’ll be a sign.”

“What kind of a sign?” Kip wondered. “Will it go guggle guggle guggle? Or shoot up like a geyser?”

“Something’ll happen,” said Laura. “We’ll know.”

There was a sound in the woods.

Everybody jumped. But it wasn’t the kind of sound magic would make starting up at all. It was a crackling and a swishing and a thudding that could add up to only one thing: Gordy.

When Gordy runs through the woods, branches don’t mean a thing to him, or noise either. As a Commando, his name would be mud. He does get where he’s going, though. And he does not seem to mind the scratches.

We could hear his voice now, high and kind of bleating the way it always is, and mingled with a childish prattle. At the sound of the prattle, the words “Oh help” rose to the lips of many.

Because fond as we are of my little sister Deborah, at a secret meeting she can be a menace. But Gordy has no sense of the fitness of things. And he indulges Deborah in her whims, and this is bad for her character.

Sure enough, when he came trotting into the clearing, we saw that he was giving Deborah a piggyback ride, a thing no one must ever do, because once you give in to her, she wants to do it all the time. They came up onto the stoop, Gordy breathing hard and forgetting to close his mouth. But I must not make personal remarks. We all have our bad habits. Lydia used to bite her nails and I drum with my fingers.

“Hi,” he said, putting Deborah down and beaming round at us. “What are you all doing? Huh?”

And right away we all got the feeling we always do when we’ve run away from Gordy and then he follows us and finds us.

It’s partly a guilty feeling, and part embarrassed and part really sorry, too. Because we like Gordy. We honestly do. Nobody could help it. It’s just that there is something about him that makes people want to pick on him. You have heard of people who are accident prone. Gordy is picking-on prone.

“Gordy rode me all the way here on his handlebars and then piggybacked me through the woods. Wasn’t thatkind?” said Deborah.

And of course it was. Gordy is just as kind as he can be. And he and Deborah get along like all get out, maybe because their childish minds meet and mingle. “Gordy said maybe you’d rather be by yourselves without him for a change, but I told him that was silly,” Deborah was saying now.

Everybody stirred uncomfortably.

“I just love Gordy,” she went on. “Don’t you?” Sometimes I think she says the things she does on purpose.

“Sure, he’s a good kid,” Kip muttered.

Gordy hung his head and said, “Aw.”

In another second I think the guilty feeling would have exploded and we might have started pushing Gordy around, just in a friendly way, and probably all joined in some childish scuffle, which is the best way to get rid of feelings.

If only Deborah had kept her mouth shut. But that is a thing she finds it impossible to do, apparently, now she is in the first grade and has learned to read. Last summer we could hardly get a word out of her.

“We’re going to have magic wishes all the time from now on,” she babbled happily. “Gordy’s fixed the well.”

There was a sound of a breath being caught and held and everyone looked at Laura. She had gone perfectly white. “What?” she said. But it did not sound like her voice talking.

“Gordy’s fixed the well,” repeated Deborah. “He went right up to it and told it what.”

“Oh,” said Laura.

Maybe I should explain right here that usually my sister Laura is the most decent and reasonable of all of us, but on the subject of the well she is different. Sometimes you would think it was her own special private property. Maybe that is because she is the one who started the wishes working in the first place.

She turned to Gordy. “All right, Gordy Witherspoon,” she said. “What have you donenow?”

Personally I consider “What have you donenow?” a perfectly awful question. If anybody said, “What have you donenow?” to me, it would make me think of all the things I had done before and I would know they had all been bad and this new thing was the worst, and that everybody hated me and I might as well go out in the garden and eat worms. But Gordy did not seem to mind.

“Oh nothing,” he said. “I just tossed a wish down.”

“He wrote it all out,” said Deborah proudly, “on the back of my spelling paper. I got a hundred. And a gold star.” Only nobody was listening because we were all watching Laura.

But “What did the wish say?” was all she asked. It was the way she said it that counted.

“Oh, nothing,” Gordy said again. “I don’t remember. Yes I do, too. I told it, ‘Get going, or else. This means you.’”

For a minute I thought Laura was going to hit him.

I decided it was time to speak up. “Let’s not get excited,” I started to say. “Maybe that was a little crude.”

“Crude?” Laura interrupted. “Crude? It just doesn’t show even the first ruminants of good taste, that’s all!”

“OK,” I said. “Maybe it doesn’t. But that’s still not a crime or anything. Gordy didn’t know about the oath. He was just trying to please Deborah. And we’ve all been ruder than that to the well in our day.”

“That’s different,” said Laura. “The magicbelongsto us. It doesn’t to him.” She turned on Gordy again. “You’ve just ruined everything utterly and completely, Gordy Witherspoon, and I hope you’re satisfied.” And then she said words I never expected to hear from a sister of mine. “You always were a buttinski and a pest and we never wanted you around in the first place, and now you can just go on home and never come back!”

This was too much for me. “Here, wait a minute,” I said, getting up and coming between them.

And even Kip, who is usually too lazy and easy-going to move, uncurled himself from the floor and went and put an arm round Gordy’s shoulder, though we all hate sloppiness and what the books call “demonstrations of affection.”

Because while it is perfectly true that we have roughed Gordy up once in a while when he needed it, and Kipdidgive him a bloody nose one day (though he got a black eye for it), and one other time when Gordy was really awful Imayhave put him across my knee and spanked him, just once or twice to help him grow up; still, neither of us would ever have spoken to a fellow human being like that. Sticks and stones may break your bones, but names and plain truths and meanness can go much deeper and cut you to the quick. We know this, and Laura knows it, too, when she is in her right mind.

But sometimes I think that Gordy does not have any quick. For he went right on smiling. Though maybe his voice did sound a little higher and more bleating than usual.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “I didn’t mean to butt in. I just thought it was time somebody did something, and you were afraid to. And Deborah wanted the wishes to start over, so I thought why not try?”

There’s one thing you can say for Gordy, he is spunky. I was sure that word “afraid” would be the last straw that would send Laura through the needle’s eye into utter frenzy. But maybe she thought she had said enough already. For she didn’t answer a word, but turned and went into the cold, dark, empty house, as if she wanted to be by herself. Gordy hesitated a minute, and then he went in after her. He certainly has spunk, all right.

Of course it would have been tactful, and better manners, to have left them to settle it on their own. But manners have never stopped Deborah. She followed Gordy right in. After that, the rest of us were too curious to be behindhand.

And besides, I wasn’t sure it was safe for Gordy to be alone with Laura, in the mood she was in.

But when we came into the secret house’s tiny parlor, Laura wasn’t doing a thing, just standing with her back to the room, looking down at the desk in one corner (the desk that was such a big part of our adventure the summer before) and fiddling with the key, moving it back and forth in the lock. Gordy went right up to her and took her by the shoulders and turned her round. He held out his hand.

“I’m sorry, honest,” he said. “I guess I just don’t know any better.”

Nobody could have said it straighter. When I thought of what Laura had just said tohim,I thought it was pretty big. And Deborah ran right up to Gordy and put her arm around his waist, which is as high up on him as she can reach.

Laura was looking at the floor. But what we could see of her face wasn’t white anymore. It was red. She hesitated. And then I’m glad to say she took Gordy’s hand, kind of grabbing at it and dropping it right away, but not as if she didn’t like him. More as if she didn’t like herself.

“I’m sorry, too,” she said.

“Oh, that’s all right,” Gordy said.

“I didn’t really mean all that,” she said.

“Sure. Of course you didn’t,” Gordy said.

“It’d be awful if I did. The magic’s supposed to be for doing good turns. It’d be awful if just thinking about it could make me say a thing like that and mean it.”

“But youdidn’tmean it,” Gordy said.

“That’s right, I didn’t. It’s just that . . .” Her voice trailed off and I thought it was time for me to step in again.

“What Laura means,” I said, “is that she was forgetting you don’t know about magic, much, yet. She was forgetting you just came in at the end of it, last summer. You see, magic has rules, the same as anything else. If you talk to it the way you did and begin ordering it around, there’s no telling what it might do. If the well starts up again now, and if it’s angry and goes wrong, it’ll be your fault and you’ll just have to bear the brunt and take the consequences.”

Laura stamped her foot. “No, silly! That’s not what I meant at all!”

“Isn’t it?” I said. But I was pleased.

“No, it isn’t.” And now she sounded like the old Laura again. “We can’t blame Gordy. He didn’t know. If it goes wrong, we’re all in it together, naturally. But if everything’s all right and it turns out to be agoodadventure, I think he ought to be in charge of the whole thing. Because he had the courage to really speak up to the well and get it going.”

That shows you what kind of girl my sister is. Particularly when everyone knew she had had dibs on the first wish right along.

It was Gordy’s face that was red now. “Aw no, you ought to be the one. Honest, I’d rather.”

Laura shook her head. “This is the only way it’d be fair.”

“How do you mean, be in charge?” Gordy said cautiously. “You’d all be along, wouldn’t you? You’d be in the adventure, too? It wouldn’t be any fun, otherwise.”

“Oh sure, we’d all be along,” Laura told him. “If the magic starts, we’ll be there and help out any way we can. But you’ll be the one to make the decisions.”

Everybody else nodded. Personally I thought it was giving Gordy a lot of rope. Still, maybe it would turn out to be just what he needed to make a man of him. So I nodded, too.

Gordy looked awed. “Gee,” he said. “I don’t know if I’m up to it.”

“Sure you are,” said Laura.

“Sure you are,” repeated Deborah.

Gordy looked down at her. They smiled at each other. Then he grinned at the rest of us. “All right,” he said. “I’ll try.”

There was a silence.

And then, in the silence, we all heard a knock at the front door.

Everybody looked at everybody else. And there wasn’t a doubt in anybody’s mind that the magic was beginning again right now.

Because nobody ever knocks at the door of the secret house.

Our parents and our friends and relations know that itissecret, and that is its charm, and they wouldn’t dream of ever coming near it and disturbing us. And besides it’s too hard a walk for most parents, through the woods and all uphill. Or downhill, if you come from behind. If we’re at the secret house and a friend or a relation wants us, he stays at the foot of the hill, by the road, and rings. We have a system, made of wires and pulleys and an old cowbell.

So if somebody had come knocking at our front door on this cold September afternoon, with the sun going down and everything getting dark, it stood to reason that only the magic could have sent him.

The knock came again.

Laura grinned at Gordy. “It’s all yours,” she said.

Gordy gulped. “Gee,” he said. Then he went into the hall and opened the front door.

And now it’s his turn to tell what happened next.

James Begins

I know people who saythey can read any kind of book except an “I” book, and sometimes I think I agree with them. When I say “I” books, I mean the kind where somebody tells the story, and it starts out, “Little did I think when I first saw the red house how large it would loom in my life.” And later on, the person sees a sinister stranger digging a grave in the garden and he says, “If I had only remembered to telephone the police next morning, seven murders might have been averted.”

Laura and I often run into books like that, and Laura always says she holds the people who tell those stories in utter contempt, which is her way of saying they give her a pain. If we saw a sinister stranger digging a grave in our garden, we would remember to telephone the police, all right. And when we first sawourred house, weknewhow large it would loom.

Laura is my sister, and not bad as sisters go. Sometimes she has quite sound ideas.

One of her ideas was that we should tell the story this way, “I” book or not. Because the things that happened that winter happened to six of us (not counting parents), and the way they happened was different for each person. The way we felt about it was different for each person, too. So it is only right that each one should tell his part.

Laura says I should begin the whole thing because I have a well-organized mind. I am not boasting. That about my mind is what Mrs. Van Nest said one day. Mrs. Van Nest is our teacher, and sometimes her ideas are quite sound, too. She lets us do book reports on any book we like, and it doesn’t have to be on the list.

So I am beginning this story, and after that each one will tell what happened to him or her, as the case may be, and each one will tell it in his own way. Only we have made one rule, which is not to tell about the days when nothing happened, because who would want to read about them? And another rule is not to put in things that don’t mean anything and are just there to try to make it more exciting. Like saying, “There I stood, my heart beating.” Naturally your heart would be beating. Otherwise you wouldn’t be standing there; you’d be lying down dead.

But we are going to stick to the facts.

The first important fact about me is that my name is James Alexander Martin and I am in grade six-one-A, Mrs. Van Nest’s homeroom. Kip and Laura and Lydia are all in my class, too, but Gordy is in six-one-B and has to have Miss Wilson. Wow, do I pity him!

We try to be specially kind to Gordy, for that and other reasons, but sometimes we forget. Gordy is not a person who makes it easy for other people always to remember. Sometimes we have to be firm with him for his own good, but we try never to stoop to physical violence. Physical violence never solved anything in the world, we all realize. But sometimes with Gordy we forget that, too, or at least Kip and I do. Girls are soft.

If you wonder why Laura and I are in the same class in school, it is because we are the same age, being twins. But we do not look alike, or think alike, either, particularly about the magic, only that comes later.

As for my other sister Deborah, she is a mere babe, just starting the first grade, and by rights she shouldn’t come into this story at all. But rights have never meant a great deal to Deborah.

The story I’m talking about began one day in fall.

Of course it really began long before that, way back at the beginning of the summer, when Laura and I and our family first moved into the red house on Silvermine Road. Before that we lived in New York City.

The red house has a well in the garden, and the day we moved in a girl called Lydia Green, who lives in a funny big old place up the road, told us that it was a wishing well. Of course I knew better than to believe that. But Laura would believe anything, or try to.

Still, some very strange things did happen that summer. A lot of quite good wishes came true and some pretty keen good turns got done. That was the way the well was supposed to work. Selfish wishes didn’t mean a thing to it.

We got our heart’s desire in the end, too, just like in that bookThe Wonderful Gardenby E. Nesbit that Laura is so crazy about. It is not a bad book, by the way. A boy runs away and so does a tiger, and a portrait comes to life. The ending is nifty, if you’re young enough to believe in magic.

I’m not sure whether I am young enough or not. Mostly I think not. Magic doesn’t seem at all like the kind of thing thatwouldbe true, when you come to think of it. Still, neither do airplanes and electric lights and outer space, when you come to think ofthem.And it’s hard to explain the things that happened that summer any other way. Or the things that have been happening since, either. Of course it may all be a coincidence, the way Kip keeps saying.

Kip is a boy called Christopher, only he never is. Never is called that, I mean. He lives on our road, too, across from Lydia. He is a good kid, and just about my best friend, I guess.

He and Lydia and Laura and I were in on the magic (if that’s what it was) from the beginning. Gordy didn’t come into it till later in the summer. We didn’taskhim in exactly, but once he was there, we didn’t mind. Sometimes his ideas are every bit as sound as ours. All he needs is to be curbed once in a while, and shoved back on the right road. He is the victim of an unfortunate environment. His mother is rich. His full name is Gordon T. Witherspoon III.

When we first made the wish about our heart’s desire, we weren’t quite sure what our heart’s desire was, but when we got it, we knew. What it turned out to be was a little old house in the woods, all our own, to have for our secret clubhouse. How we found the house in the first place, and what we found in it, and exactly how it got to be ours is another story, and if you want to read that story, you will have to get a book calledMagic or Not?that tells all about it. But we did not write that book ourselves; so it does not have all our thoughts in it, the way this book will.

The part about the heart’s desire came right at the end of the summer, and after that the magic (if itwasmagic) seemed to be played out. At least we made quite a few perfectly good wishes on the well and they never came true, no matter how noble. That was all right with me, if that was how the well wanted things to end. But the girls said it was probably just resting and would start up again one day when we least expected it. You never can tell with magic. Or not, as the case may be.

And then suddenly it was fall, and for Laura and me there was a new school to get used to, and learning a new teacher’s ways and how to circumscribe them, if that is the word I mean, and that took up all our thoughts, for a while.

Football season began, too; so Kip and I were mainly too busy to bother with girls. I play end, but not very often, being light though rangy. Baseball is my game.

Laura and Lydia do not understand the true importance of football, or baseball either, but that is their female folly. As you grow older, the sexes grow farther and farther apart, I find. It is all part of maturing.

Still, the old group did find time to meet now and then in the house in the woods and have secret conclaves, though there wasn’t very much to conclavefor,now that the magic was a thing of the past.

Maybe that’s how we got into the habit of leaving Gordy out; so we’d have something to be secret about. We even had a mysterious secret sign. When it seemed like a good day for a meeting, one of us would hold up one finger, or two, along toward the end of last period. One if all five, two if without Gordy. Lately it was getting to be two most of the time.

Sometimes Gordy would come into the woods looking for us, but when he found us in the secret clubhouse without him, he never seemed to bear any grudge. That is one of the good things about Gordy.

We were always sorry afterward when this happened, and the fact that Gordy didn’t seem to get hurt or mad at us made us feel sorrier. You would think that would make us be nicer to him from then on, but it didn’t. The sorrier we felt each time, the more we went on leaving him out the next. That is the way people are. I do not think this is right, but it is true all the same. Though unfortunate.

This particular day Kip had held up two fingers just as the last bell rang, and we had all nodded, and when we marched out, everybody but Lydia got away quick without being spotted by the enemy. And Lydia crossed her fingers and told Gordy she had to go to the dentist. Which was not a lie really, because shedidhave to go. Only not that day.

So now there we all were (except you know whom) sitting on the front stoop of the secret house, because it was getting to be late September and the rooms inside were cold. But in front, the woods have been cut away to let the sun through.

Lydia had a pencil in her hand and a sketchbook in her lap, the way she does all the time now that she knows she has talent. It is wonderful how learning that she has talent has changed that girl. Maybe learning to make friends has had something to do with it, too. When we first met her, she was plain ornery, always doing crazy things just to be different, and quarreling with everybody. She is still ornery once in a while, and she and I still argue some. But she is a good kid, for a girl.

Today she was amusing us by doing caricatures of each one. The ones she did of Laura and Kip were awfully funny, but she didn’t get me right at all. My chin doesn’t stick out like that, at least not that far.

When we’d finished arguing about my chin, she started a portrait of herself, all long tangled blond hair with a scowl peeking through. Then she made a face at it and tore it up. “If you ask me,” she said, “it’s time something started happening around here. I’m used to school again. The sameness has set in.”

“Halloween next month,” Kip reminded her. “There’s the party in the gym.”

“Bobbing for apples!” Lydia was scornful. “And that old decoration committee. Black crepe paper cats on the walls; you’d think they could at least think up something original. Why didn’t they putmeon it;I’dfreeze their marrow for them!” And she drew a truly horrendous witch on the next page of her sketch pad.

“If you askme,” said Laura, “I think the trouble with us is we miss the magic.”

Everybody groaned, because we were all secretly trying not to think about that. But Laura is a great one for bringing hidden thoughts out into the open.

“We said this was going to be our secret witches’ den where we’d have midnight meetings and plan our secret spells,” she went on now. “We were going to do good turns to the whole town. But not a single magic thing’s happened, and pretty soon it’ll be too cold to come here anymore.”

“It’ll be warm again in the spring,” I said. “Maybe the magic goes to sleep in the winter, like woodchucks.”

“In books it’s almost always summer when the magic starts working,” put in Kip. “It’s almost always summer vacation.”

“So we won’t be distracted from our lessons, I suppose,” said Lydia bitterly. “As if being distracted weren’t just what we need!”

“Has anybody said anything to the well lately?” I wondered. “Maybe it’s just sitting there waiting for a friendly word.” After all, if we were going to believe in the magic (and everyone was talking suddenly as if we were), we might as well be efficient about it.

“No, and I don’t think we ought to,” said Laura. “I think we’re supposed to wait, no matter how long it takes.”

“Then let’s not talk about it,” I said. Because there is nothing so maddening as talking about something when you can’t do a single thing about it.

“I think weoughtto talk,” said Laura. “I think we’ve been silent about it, and each going his own way, long enough.” She turned to Lydia. “You didn’t say a thing when James asked if anybody’d been talking to the well lately, and neither did Kip. Have you been wishing on the sly?”

“I did think of giving it a look and a few words the other day,” Lydia admitted. “Just sort of generally about getting a move on. But I thought better of it.”

“I almost asked it to help with my history test,” said Kip. “And that would have been unselfish, because think how my parents would feel if I flunked. I didn’t do it, though. Maybe I should have. I only got a seventy-one.”

“No,” said Laura. “I think it’s a good thing you didn’t. I think if we start pestering it, it might get cross and take longer waking up than it would have, even. Or go all wrong when it does. I think we ought to swear a secret oath in blood not to gonearthe well until we’re absolutely sure it’s time.”

Everybody was willing, probably because even merely swearing a secret oath issortof a secret adventure. Kip had his scout knife handy, pricks were made, and the fatal oath duly sworn.

“There,” said Laura, sucking a finger. “That’s settled. Now when the well’s ready, it’ll tell us so. There’ll be a sign.”

“What kind of a sign?” Kip wondered. “Will it go guggle guggle guggle? Or shoot up like a geyser?”

“Something’ll happen,” said Laura. “We’ll know.”

There was a sound in the woods.

Everybody jumped. But it wasn’t the kind of sound magic would make starting up at all. It was a crackling and a swishing and a thudding that could add up to only one thing: Gordy.

When Gordy runs through the woods, branches don’t mean a thing to him, or noise either. As a Commando, his name would be mud. He does get where he’s going, though. And he does not seem to mind the scratches.

We could hear his voice now, high and kind of bleating the way it always is, and mingled with a childish prattle. At the sound of the prattle, the words “Oh help” rose to the lips of many.

Because fond as we are of my little sister Deborah, at a secret meeting she can be a menace. But Gordy has no sense of the fitness of things. And he indulges Deborah in her whims, and this is bad for her character.

Sure enough, when he came trotting into the clearing, we saw that he was giving Deborah a piggyback ride, a thing no one must ever do, because once you give in to her, she wants to do it all the time. They came up onto the stoop, Gordy breathing hard and forgetting to close his mouth. But I must not make personal remarks. We all have our bad habits. Lydia used to bite her nails and I drum with my fingers.

“Hi,” he said, putting Deborah down and beaming round at us. “What are you all doing? Huh?”

And right away we all got the feeling we always do when we’ve run away from Gordy and then he follows us and finds us.

It’s partly a guilty feeling, and part embarrassed and part really sorry, too. Because we like Gordy. We honestly do. Nobody could help it. It’s just that there is something about him that makes people want to pick on him. You have heard of people who are accident prone. Gordy is picking-on prone.

“Gordy rode me all the way here on his handlebars and then piggybacked me through the woods. Wasn’t thatkind?” said Deborah.

And of course it was. Gordy is just as kind as he can be. And he and Deborah get along like all get out, maybe because their childish minds meet and mingle. “Gordy said maybe you’d rather be by yourselves without him for a change, but I told him that was silly,” Deborah was saying now.

Everybody stirred uncomfortably.

“I just love Gordy,” she went on. “Don’t you?” Sometimes I think she says the things she does on purpose.

“Sure, he’s a good kid,” Kip muttered.

Gordy hung his head and said, “Aw.”

In another second I think the guilty feeling would have exploded and we might have started pushing Gordy around, just in a friendly way, and probably all joined in some childish scuffle, which is the best way to get rid of feelings.

If only Deborah had kept her mouth shut. But that is a thing she finds it impossible to do, apparently, now she is in the first grade and has learned to read. Last summer we could hardly get a word out of her.

“We’re going to have magic wishes all the time from now on,” she babbled happily. “Gordy’s fixed the well.”

There was a sound of a breath being caught and held and everyone looked at Laura. She had gone perfectly white. “What?” she said. But it did not sound like her voice talking.

“Gordy’s fixed the well,” repeated Deborah. “He went right up to it and told it what.”

“Oh,” said Laura.

Maybe I should explain right here that usually my sister Laura is the most decent and reasonable of all of us, but on the subject of the well she is different. Sometimes you would think it was her own special private property. Maybe that is because she is the one who started the wishes working in the first place.

She turned to Gordy. “All right, Gordy Witherspoon,” she said. “What have you donenow?”

Personally I consider “What have you donenow?” a perfectly awful question. If anybody said, “What have you donenow?” to me, it would make me think of all the things I had done before and I would know they had all been bad and this new thing was the worst, and that everybody hated me and I might as well go out in the garden and eat worms. But Gordy did not seem to mind.

“Oh nothing,” he said. “I just tossed a wish down.”

“He wrote it all out,” said Deborah proudly, “on the back of my spelling paper. I got a hundred. And a gold star.” Only nobody was listening because we were all watching Laura.

But “What did the wish say?” was all she asked. It was the way she said it that counted.

“Oh, nothing,” Gordy said again. “I don’t remember. Yes I do, too. I told it, ‘Get going, or else. This means you.’”

For a minute I thought Laura was going to hit him.

I decided it was time to speak up. “Let’s not get excited,” I started to say. “Maybe that was a little crude.”

“Crude?” Laura interrupted. “Crude? It just doesn’t show even the first ruminants of good taste, that’s all!”

“OK,” I said. “Maybe it doesn’t. But that’s still not a crime or anything. Gordy didn’t know about the oath. He was just trying to please Deborah. And we’ve all been ruder than that to the well in our day.”

“That’s different,” said Laura. “The magicbelongsto us. It doesn’t to him.” She turned on Gordy again. “You’ve just ruined everything utterly and completely, Gordy Witherspoon, and I hope you’re satisfied.” And then she said words I never expected to hear from a sister of mine. “You always were a buttinski and a pest and we never wanted you around in the first place, and now you can just go on home and never come back!”

This was too much for me. “Here, wait a minute,” I said, getting up and coming between them.

And even Kip, who is usually too lazy and easy-going to move, uncurled himself from the floor and went and put an arm round Gordy’s shoulder, though we all hate sloppiness and what the books call “demonstrations of affection.”

Because while it is perfectly true that we have roughed Gordy up once in a while when he needed it, and Kipdidgive him a bloody nose one day (though he got a black eye for it), and one other time when Gordy was really awful Imayhave put him across my knee and spanked him, just once or twice to help him grow up; still, neither of us would ever have spoken to a fellow human being like that. Sticks and stones may break your bones, but names and plain truths and meanness can go much deeper and cut you to the quick. We know this, and Laura knows it, too, when she is in her right mind.

But sometimes I think that Gordy does not have any quick. For he went right on smiling. Though maybe his voice did sound a little higher and more bleating than usual.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “I didn’t mean to butt in. I just thought it was time somebody did something, and you were afraid to. And Deborah wanted the wishes to start over, so I thought why not try?”

There’s one thing you can say for Gordy, he is spunky. I was sure that word “afraid” would be the last straw that would send Laura through the needle’s eye into utter frenzy. But maybe she thought she had said enough already. For she didn’t answer a word, but turned and went into the cold, dark, empty house, as if she wanted to be by herself. Gordy hesitated a minute, and then he went in after her. He certainly has spunk, all right.

Of course it would have been tactful, and better manners, to have left them to settle it on their own. But manners have never stopped Deborah. She followed Gordy right in. After that, the rest of us were too curious to be behindhand.

And besides, I wasn’t sure it was safe for Gordy to be alone with Laura, in the mood she was in.

But when we came into the secret house’s tiny parlor, Laura wasn’t doing a thing, just standing with her back to the room, looking down at the desk in one corner (the desk that was such a big part of our adventure the summer before) and fiddling with the key, moving it back and forth in the lock. Gordy went right up to her and took her by the shoulders and turned her round. He held out his hand.

“I’m sorry, honest,” he said. “I guess I just don’t know any better.”

Nobody could have said it straighter. When I thought of what Laura had just said tohim,I thought it was pretty big. And Deborah ran right up to Gordy and put her arm around his waist, which is as high up on him as she can reach.

Laura was looking at the floor. But what we could see of her face wasn’t white anymore. It was red. She hesitated. And then I’m glad to say she took Gordy’s hand, kind of grabbing at it and dropping it right away, but not as if she didn’t like him. More as if she didn’t like herself.

“I’m sorry, too,” she said.

“Oh, that’s all right,” Gordy said.

“I didn’t really mean all that,” she said.

“Sure. Of course you didn’t,” Gordy said.

“It’d be awful if I did. The magic’s supposed to be for doing good turns. It’d be awful if just thinking about it could make me say a thing like that and mean it.”

“But youdidn’tmean it,” Gordy said.

“That’s right, I didn’t. It’s just that . . .” Her voice trailed off and I thought it was time for me to step in again.

“What Laura means,” I said, “is that she was forgetting you don’t know about magic, much, yet. She was forgetting you just came in at the end of it, last summer. You see, magic has rules, the same as anything else. If you talk to it the way you did and begin ordering it around, there’s no telling what it might do. If the well starts up again now, and if it’s angry and goes wrong, it’ll be your fault and you’ll just have to bear the brunt and take the consequences.”

Laura stamped her foot. “No, silly! That’s not what I meant at all!”

“Isn’t it?” I said. But I was pleased.

“No, it isn’t.” And now she sounded like the old Laura again. “We can’t blame Gordy. He didn’t know. If it goes wrong, we’re all in it together, naturally. But if everything’s all right and it turns out to be agoodadventure, I think he ought to be in charge of the whole thing. Because he had the courage to really speak up to the well and get it going.”

That shows you what kind of girl my sister is. Particularly when everyone knew she had had dibs on the first wish right along.

It was Gordy’s face that was red now. “Aw no, you ought to be the one. Honest, I’d rather.”

Laura shook her head. “This is the only way it’d be fair.”

“How do you mean, be in charge?” Gordy said cautiously. “You’d all be along, wouldn’t you? You’d be in the adventure, too? It wouldn’t be any fun, otherwise.”

“Oh sure, we’d all be along,” Laura told him. “If the magic starts, we’ll be there and help out any way we can. But you’ll be the one to make the decisions.”

Everybody else nodded. Personally I thought it was giving Gordy a lot of rope. Still, maybe it would turn out to be just what he needed to make a man of him. So I nodded, too.

Gordy looked awed. “Gee,” he said. “I don’t know if I’m up to it.”

“Sure you are,” said Laura.

“Sure you are,” repeated Deborah.

Gordy looked down at her. They smiled at each other. Then he grinned at the rest of us. “All right,” he said. “I’ll try.”

There was a silence.

And then, in the silence, we all heard a knock at the front door.

Everybody looked at everybody else. And there wasn’t a doubt in anybody’s mind that the magic was beginning again right now.

Because nobody ever knocks at the door of the secret house.

Our parents and our friends and relations know that itissecret, and that is its charm, and they wouldn’t dream of ever coming near it and disturbing us. And besides it’s too hard a walk for most parents, through the woods and all uphill. Or downhill, if you come from behind. If we’re at the secret house and a friend or a relation wants us, he stays at the foot of the hill, by the road, and rings. We have a system, made of wires and pulleys and an old cowbell.

So if somebody had come knocking at our front door on this cold September afternoon, with the sun going down and everything getting dark, it stood to reason that only the magic could have sent him.

The knock came again.

Laura grinned at Gordy. “It’s all yours,” she said.

Gordy gulped. “Gee,” he said. Then he went into the hall and opened the front door.

And now it’s his turn to tell what happened next.