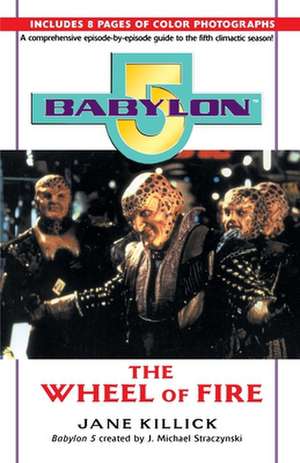

The Wheel of Fire: Babylon 5 (Paperback Ballantine), cartea 05

Autor Jane Killicken Limba Engleză Paperback – 28 feb 1999

As the action surrounding Babylon 5 reaches the boiling point, Babylon 5: The Wheel of Fire sums up the last stunning season of the history-making series that started it all, thus setting the stage for the exciting B5 offshoot, Crusade. Episode by episode, Jane Killick offers a breathtaking look back at all the action, plot twists, and life-altering events that set the stage for the future of the Babylon 5 universe: Byron and his rogue telepaths' demand for a homeworld; Elizabeth Lochley's assignment as captain of Babylon 5; Sheridan's inauguration as president of the uneasy Interstellar Alliance; G'Kar's unwilling ascension to the role of messiah; and clandestine political intrigue on Centauri Prime.

Veteran viewers or first-time fans, relive the adventure--or find out what you've been missing--with the complete companions to Babylon 5!

Preț: 88.08 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 132

Preț estimativ în valută:

16.85€ • 18.36$ • 14.20£

16.85€ • 18.36$ • 14.20£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 02-16 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780345424518

ISBN-10: 0345424514

Pagini: 192

Dimensiuni: 141 x 217 x 12 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Editura: Del Rey Books

Seria Babylon 5 (Paperback Ballantine)

ISBN-10: 0345424514

Pagini: 192

Dimensiuni: 141 x 217 x 12 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Editura: Del Rey Books

Seria Babylon 5 (Paperback Ballantine)

Extras

Foreword: Looking Back Over Five Years

When Babylon 5 began, in 1992, many claimed that the series was destined to fail, Babylon 5 creator J. Michael Straczynski recalls. "The odds against us were considerable. I was saying, 'This is going to be a five-year show, period.' They would say, 'What makes you think you will get five years out of this?' [I'd reply] 'We're on a mission from God, okay?'" [Starburst, special 35]

The very achievement of making the show last its full, planned five years has been incredibly important for the people who lived through it. Few shows make it that far--and Babylon 5 nearly didn't. The threat of cancellation was always hanging over it and nearly destroyed it altogether at the end of the fourth year. It was only pulled back from the brink by a change of network, from Warner Bros.' PTEN consortium to cable channel TNT when the former network collapsed. But the commercial success that kept producers, cast, and crew employed for five years is only a side issue in Babylon 5's achievement. Its main success has been fulfilling the story plan that lay at the heart of the show, its famous "five-year arc."

The phrase "five-year arc" has become so synonymous with the show that it tends to get trotted out in a blase fashion. But back in 1992, this was a new concept. Some shows, particularly soap operas, used continuous story lines that progressed with each episode and were often planned as much as two years ahead. But no one had attempted a story on such a grand scale, where the plot points introduced in the beginning would continue to play a significant part throughout the show's entire length until it reached a predetermined conclusion. Television is a fickle business where shows can be canceled on a whim without warning, leaving the rest of the story untold. Television audiences themselves can be fickle, flitting from channel to channel, picking up on a program halfway into its season or missing the odd episode, and so finding it difficult to follow an ongoing story. Then there are production considerations, like the risk the story line is going to be wrecked by the lead actor getting run over by a bus or the producers wanting to change direction after judging the response of the audience. But Joe Straczynski had worked out his story in such detail that he had faith it could work, and with his famous "trap doors" for every character, he could keep his story on track no matter what production considerations intervened. No one actually had an unpleasant encounter with a bus, thankfully, but when there was a need to replace Sinclair with Sheridan, and when the actress playing Talia Winters (Andrea Thompson) wanted to leave to pursue other work, the trap doors came into play and the story continued because it was the story that was important.

And it was the story that excited audiences. The idea of a story arc that lasted five years may have sounded daunting to the television industry, but it hooked viewers in a way that few television programs ever achieve. "We were able to tell a story over five years where things were foreshadowed in year one and it paid off in year three, in a medium where often you set things up in the teaser and pay it off two acts later," Joe says. "We extended it by years and the audience follows it and gets it ... We can say to the television community, 'You're wrong--the viewers are not morons, they're sharp people. If you would teach them and talk to them in a straightforward fashion they will react and come to you.' And they have done that." [Cult Times, issue 31]

This fresh approach to storytelling kept people talking about Babylon 5 down at the pub, over the phone, and on the Internet. Speculation about what was going to happen next, what was the meaning of a certain line of dialogue or a certain scene became more profound precisely because it was all planned out ahead of time. Viewers developed their own theories about everything: What was Kosh hiding under his encounter suit? Could he be an angel? How did he know so much about the future? Could it be that the Vorlons age backwards? Is his apparently benevolent nature hiding his true dark side? It was a series that got people involved, made them think, and kept them coming back week after week for the next installment. It was an intricate story in which every detail could have significance, where watching and rewatching the episodes could provide new insight. "We proved we were right, right on the production, right on the story," Joe says. "They said it would never work. Now, of course, Dark Skies said they had a five-year arc, the new Roddenberry show [Earth: Final Conflict] has a five-year arc--this term has now entered the vernacular. We have created something new. That's a good thing." [Cult Times, issue 31]

What was also new for science fiction television was Babylon 5's nod of respect to the tradition of the written genre. For a long time, even into the nineties, science fiction television was regarded as something for kids. It was about rockets, robots, and ray guns, people with silly costumes and annoying whizkids. That's not to denigrate the many excellent series that preceded Babylon 5--indeed, some of them such as Blake's 7 directly influenced it--but that perception continued to exist and be reflected in some of the shows getting on the air. Babylon 5 broke through that barrier and tapped into an audience that had been brought up on written science fiction. The aliens were real aliens. They may have been limited by the practicalities of a television show in that they had to be played by a human actor--although Kosh was an acknowledgment of that restriction, with his true form hidden under the encounter suit--but they were three-dimensional, with a culture and a philosophy all their own. They walked onto Babylon 5 with a fully sketched background that gave them a depth and a believability rare in science fiction television. The aliens are not simply a metaphor for a part of human nature--e.g., a "warrior race"--but complex peoples with different facets that are gradually revealed. Moreover, the individuals of these alien races have their own personalities, so both G'Kar and Na'Toth are decisively Narn in the way they behave, but are also characters in their own right.

It is clear that the people behind the show understand science fiction. Not only does Babylon 5 get the terminology right--even Star Wars thought a parsec was a length of time, when it's actually a measurement of distance--it also has respect for the concepts that have developed within the genre over the years. In other shows, telepaths tend to be people who can do clever things with their minds, but in Babylon 5, the implications of what it might mean to be telepathic, both to the individual and society, are taken into account. This is a testament partly to the amount of thought put into the framework of Babylon 5 and partly to the tradition of science fiction literature. The Psi Cop played by Walter Koenig is even named in tribute to Alfred Bester, the author of the seminal telepath novel The Demolished Man.

Some of the key people on the show, including Joe Straczynski and producer John Copeland, were fans before they were ever television producers, and it is an enthusiasm that can be seen on the screen. "We brought that passion, our passion for man's exploration of space, our imaginations that were stretched by reading science fiction and fantasy growing up, here to this show," John says. "I know Joe is an avid reader and I think that all translated into this show. This is a thinking person's show, this is a smart show. This is a show that deals with the types of material and things that you normally encounter in books, and that's not the case with most science fiction which is on television, or has been on television, or has been in the movie theater. A lot of them are just shoot-'em-up action adventure stories. I think that folks that read science fiction tend to be brighter, are more thoughtful about things, and you have to deliver that to them if you want them to buy into your show. It has to be a smart and interesting and intelligent show, and I think we've tried to do that here."

The intelligence lies in the nature of the story. Science fiction has often been described as a genre of ideas, and Babylon 5 always delivered compelling ideas, whether they were in the truth about the Vorlons and/or in Sinclair's destiny to become Valen. They stretched the mind and resonated in today's world. If Babylon 5 has achieved its aim in telling a great story, then it has also said something to its audience along the way. Joe Straczynski said he wanted to show that choices have consequences that bring responsibilities, and that theme is explored over and over again. The most demonstrative example of this is probably Londo's story. He hoped his alliance with the Shadows would return the Centauri to greatness, but it only took them into a war that threatened his Homeworld and eventually pulled Londo down with it, to face his responsibility as an aging, ailing emperor of a ravaged people. If you want to sit back and enjoy the adventure, that is fine, but if you want to look deeper there are other issues to consider.

One of the things that science fiction does so well is comment on the present day at one remove, whether that comment be about racism and the benefits of working together, or about the realities of war. It also shows there are no easy answers. Where a traditional television episode might end on a moral high note with a pat answer to a problem, Babylon 5 presents an issue in shades of grey, where there is not always a right answer. One early example is Season One's "Believers," where Franklin must decide whether to save a child against his religious beliefs or let him die. "That's the wonderful thing about doing a story that is set in the future," John Copeland says. "That is something that is done again and again in great works of science fiction. They pose the same moral dilemmas and deal with issues that you're able to look at from a different perspective and it's not sucked into your culture with your nationality wrapped around it. In some ways they [the stories] are extremely moral and other ways they are frustratingly amoral because they become much more like life that way. It's not 'good' or 'bad,' it's grey, and endings don't always necessarily become happy endings, they're just endings. It's like everybody wants to have a happy life--well, you don't, you just have a life."

Babylon 5 has never been afraid to reach a new level of storytelling, whether by breaking the simplistic view that the villains are always the villains and the good guys are always straight or true, or by the unconventional use of flash-forwards. Babylon 5 has been bold and brave with its storytelling, and if one or two elements failed to hit their mark, they are far overshadowed by its successes. The old adage that a story must have a beginning, a middle, and an end, but not necessarily in that order, certainly applies here. In the early days when the show was working hard to set up its complex world, there were hints and visions--"Signs and Portents"--of the great arc that was developing in the background. Later, when the elements of the story were coming together, hints of the future served to intensify the arc. The supreme example of this is "War without End," when Sheridan is thrust forward in time to Centauri Prime where he is a prisoner and Londo is emperor of the devastated planet. Suddenly a whole new set of questions is displayed before the audience.

And then there are the characters. Perhaps it is obvious to say that a drama without good characterization is not dramatic at all, but that has been a flaw of many a science fiction project and television adventure show in the past. In Babylon 5, the people are just as important as the plot--they are affected by the plot, and the plot affects them, until the two are so interwoven that one is part of the other. Each person is vividly drawn, from Londo's characteristic quirk of turning a statement into a rhetorical question--as in, "your recent alliance with Mr. Morden, yes?" to Refa in "Ceremonies of Light and Dark"--to Garibaldi's troubled, alcoholic past. The characters also progress in a way that is rare in television. In a normal episodic television show, where the characters begin at the start of the episode is where they have to end at the end of it. The whole format of an episodic show, designed to appeal to the casual viewer, dictates that to be the case. But with Babylon 5, the arc of the show is also the arc of the characters. They progress, they learn, and they are affected by what happens around them. Two characters, Delenn and Sinclair, even change species! It is the essence of storytelling for novels, plays, and films, but has never traditionally been the resolve of television. The characters in Babylon 5 are vivid, complex, and encourage the audience to take the journey with them. Without such effective characterization, the show would lack much of the depth that is its hallmark.

Babylon 5 has become a landmark in science fiction television, through its approach to both story and production. It was one of the main players in the science fiction boom of the mid-1990s and proved that there was a market out there for intelligent science fiction. For John Copeland, who had spent years trying to sell different science fiction shows to TV networks with fellow producer Douglas Netter, it has been a truly satisfying experience. "What Babylon 5 achieved is to really put a point on the end of the sentence that there is an audience worldwide for science fiction television programming that is not Star Trek," he says. "For the longest time they all thought in the executive suites that Star Trek was its own unique phenomenon. I think as a result of B5 coming on the air, it has made it possible for shows like Space: Above and Beyond and for things like Sliders. We've helped pave the way, along with The X-Files."

Babylon 5's use of special effects has been another one of its achievements. One of the reasons why television networks were skeptical of putting money into science fiction was that they knew how expensive it was to generate special effects. Babylon 5 came in with a new approach, using computer graphics (CGI). It was uncharted territory, and even the man who spearheaded B5's CGI look, Ron Thornton, secretly wasn't entirely sure how he was going to do it. But the result gave a unique look to the series, and the new technique enabled them to do the sort of shots that would have been impossible with traditional model work. Now everyone's doing it. "The thing that has been done with Babylon 5 is to say that you can look at new ways of doing things and be successful," John Copeland says. "There were many people who said, 'Oh you're going to do all computer effects and it's not going to work, it's going to be terrible.' Now you look at Space: Above and Beyond, which came along two years after us, and they tried to go down the exact same road as we did with all digital effects. I think we have shown that these technologies are embraceable for television, that you can manage them within the restraints of a television budget and within a television schedule."

But, in the end, the success of Babylon 5 will be measured by the story it told. "I wanted to create a myth for television on the scale of the Lord of the Rings books or the Foundation books," Joe Straczynski says, and after five years, that was what he had done. It was a large-canvas story that looked back as far as the first sentient beings in the galaxy, followed mankind into a new age, and looked forward to the destruction of the Earth and humanity's transition into a higher form. It spanned alien races with different philosophies, different cultures, and different faces. It saw characters die, be resurrected, fall in love, be betrayed, and fulfill their destiny. The story gave us the Babylon 5 station, which began as our last, best hope for peace; became our last, best hope for victory; then rose from the ashes of a war to head the push for stability and a new Interstellar Alliance. It is a story that is not entirely over because there will be spinoffs, but it is a story that has been concluded. Perhaps one should leave the last word to its creator, J. Michael Straczynski.

After completing the final-ever episode of Babylon 5, "Sleeping in Light," he told fans: "I think ... people will look back at the whole story, through all these long years and say 'It was a good story' and close the cover and put it on the shelf with the other books ... and turn off the lights and go to bed feeling that the time was well spent. Which is the most any writer can ever ask for. To tell a tale worth telling, to make people cry, to make people laugh. And even, once in a while, make them think about things and see the world just a little differently than when they began.

"Everything I set out to say, I said. I've carried this story like a hermit crab carries its shell for six long years, counting the pilot. It's been an awfully long and difficult road, and no one will ever really know just how hard the show was to make. Nor should they, because it isn't the difficulty that makes the story, the story makes the story. But one way or another ... when it airs, the burden is off at last. Then it no longer belongs to me. It belongs to you. As it should be. And, in the end, I think you'll be pleased."

"It's these people. I've worked with them a long time, they're like your family and you see them all the time, and that will be the hardest stuff to leave behind. I won't miss Londo, Londo got to play it out, he found his way to the throne, but I will miss the people."

--Peter Jurasik, Londo

"I've experienced tremendous growth as an actor. I don't even think you can find that in the theater because you never stay with a character long enough. A play is only two hours, but we've had one hundred and ten hours--what a chance to really get into a character and take it through every situation, every twist and turn. So I am just totally grateful for this experience."

--Andreas Katsulas, G'Kar

"I think in the long run Babylon 5 will be looked at and remembered as one of the very best--if not the best--television science fiction series ever made. I'm very proud to be a part of it."

--Bill Mumy, Lennier

"When I first came on the show I had three lines and I turned down two other jobs to do the show because I just really wanted to do it. It was like walking into a comic book. That whole first year was kind of like a mystical experience for me. Every time they called me to come to work, I'd get so thrilled and excited, and I'd turn down other work at times to do the show. This is so much fun to put on this uniform and be a space cop. Man, this is like a dream come true!"

--Jeff Conaway, Zack

"Most important of all has been making friends; good, long-term, solid friends. I love coming to work every day. We have a really close group here and even though we all got into it knowing it was a five-year arc, it's still very sad to see a family break up. No matter where I go I'm always going to take the energy and enthusiasm and the camaraderie of this set with me."

--Jerry Doyle, Garibaldi

"It's been an incredible journey. In Blackpool they've got this big old roller coaster and everyone had to ride it. When you come off, you encourage all your friends 'You gotta go ride the big one.' Babylon 5's the big one and everyone's been telling their friends 'You gotta watch it,' so slowly but surely we're gaining popularity. It's been an amazing ride."

--Patricia Tallman, Lyta

"I think I'll remember the five years I was on Babylon 5 as being part of a phenomenon, of a science fiction chapter that will go down as, I think, a positive addition to the science fiction television genre. I am lucky enough and fortunate enough to be part of that, and that brings a smile to my face."

--Richard Biggs, Franklin

"I get very attached to my job and my work and I'm sad that it's ending. The highlights for me are, number one, getting the chance to direct, number two, to be involved in such a wonderfully rich show, and number three, making friends."

--Stephen Furst, Vir

"It's been a wonderful experience for me. Joe wrote beautiful stuff for me that really touched me and moved me and had so much to do with my own experience. I agree with him so much, and sometimes I think he wrote it exclusively for me."

--Mira Furlan, Delenn

"This has been the greatest. I am very sad that it's over. I'm very proud to have been on it. This was a great place, a great bunch of people to work with, and you don't get that very often. In my twenty-seven years as a professional actor, this is one of the good ones that I will remember."

--Bruce Boxleitner, Sheridan

Babylon 5's Fifth Season

It had been a hard struggle to get a commission for a fifth and final season of Babylon 5. The previous year had been full of uncertainties, with the prospect of cancellation looming so large that portions of the story were slipped into the fourth season to bring the series to a satisfactory conclusion. It was a wise move, had Warner Bros. declared themselves unwilling to stump up the money for more episodes. With the collapse of PTEN, the show had to find a new venue to survive. U.S. cable channel TNT eventually came through at the eleventh hour, having previously obtained the rights to show the first four seasons. This secured a dedicated home for the show and greater exposure in its home country. But after the celebrations died down, one question remained: With some elements of the story moved up into the fourth year, could there really be more story to tell?

The creative force behind the series, writer and executive producer J. Michael Straczynski, had prepared for this moment. In squeezing what story he could into the fourth year, he always knew it was possible that the powers that be would come to their senses and let him have the fifth season he so desired. The remaining story elements planned for Season Five were still untouched. Most obviously, these included the increasing tensions between telepaths and normals--or "mundanes" as they increasingly became known during the fifth season--set up during the preceding seasons, the creation of the new Interstellar Alliance, and Londo's final descent into darkness. After Season Four's frantic pace, the hope was that Season Five was going to be slower and more reflective.

The main arcs for Season Five are the telepath struggle, Londo's rise to power, the bumpy first year of Sheridan's presidency, and the Drakh war. The trouble between telepaths and normals had been building for some time--Lyta had predicted it back in Season Four, and "The Deconstruction of Falling Stars" confirmed that one day there would be a war between telepaths and normals. It is a powder keg waiting to explode, and the spark arrives on Babylon 5 in the shape of Byron. He, himself, is a nonviolent, almost religious figure, but the tension between the two species of humanity is too much to contain even for him. Normals fear telepaths, a fear that has traditionally been tempered by forcing them to join the Psi Corps where they are bound by rules that protect the ordinary citizen. But rogues present a different face: a group of people with extra powers, free to use those powers at their whim. The response to Byron and his followers is inevitable.

This is the type of situation Babylon 5 handles so well, a dilemma where there is no black and white, and no clear solution that can produce a happy ending for all sides. The Psi Corps, as we have seen, can be an oppressive organization and the rogues only want a place to stay and hide from repression. Making a home on Babylon 5 is not easy, and they are immediately confronted with ignorance and prejudice from the bully boys--or "bad guy types," as the scripts often refer to them--in Down Below. In such circumstances, who could fail to sympathize with the rogues, especially when they have such a charismatic, eloquent leader as Byron? He may borrow some of his nice words from the great writers of history, but the words are powerful, enough to command loyalty from the others and draw in Lyta.

Lyta has come to the stage where she has closed herself off to emotion. She risked herself to try to find Sheridan when he fell at Z'ha'dum, she was an important asset during the Shadow War and instrumental in the final battle in Earth's civil war, but still she found little comfort in the nontelepaths she helped. She was forced back into the Psi Corps to survive, and it is not surprising that she tells Byron, "I don't let anybody in anymore." But gradually she's drawn to his charm, finding hope in his philosophy and love for someone who truly cares for her, not for her powers. Finally, she is able to let someone in, in the most intimate way possible, not only sharing her body with him, but also taking down the barriers in her mind, opening a window to the secrets she had been hiding. This sex scene is one of the most enduring images of the season and something uncharacteristic for Babylon 5. It reveals to Byron and his followers that the Vorlons were responsible for creating telepaths and sets the scene for confrontation and tragedy.

Byron has good reason to ask for a Homeworld for telepaths and, on the surface, it would seem to be an acceptable solution to the tensions that have grown up between telepaths and normals. But there is a fatal flaw in his argument. He sincerely believes that telepaths are better than normals, that violence is not their way. But the truth is that evolution may have given them extra talents, but it has not divorced them from human nature. Desperation leads a group of them to respond to their human instincts and turn to violence. From that moment, Byron's cause is doomed. Captain Lochley, left with a hostage situation on her hands, does the only thing she can do to stop the station being held to ransom by terrorists--she calls in Bester and the Psi Cops. It brings the situation to an ugly end. Byron destroys himself, putting an end to the trouble for the moment, but ensuring that his name and his cause live on. He, as Zack predicted the moment he stepped onto the station, has become a martyr. And there Babylon 5 leaves the telepath situation. Its influence lives on, of course, in Lyta, in her hardened determination to achieve a Homeworld for her people.

Then comes the Drakh war--not so much a war; more of a diplomatic crisis for the new Interstellar Alliance, driven by a series of terrorist-like attacks. The characteristic way Babylon 5 builds seemingly small incidents into something potentially devastating is equally effective here. The end of the fourth season left the audience with a sense of closure, and although some matters were left unresolved, it was a satisfactory ending. In bringing the story back up to speed again and introducing new threads, Babylon 5 asks the audience to be patient.

This same trick was used in the first and second seasons, where the series was starting with a blank slate. All was discovery and mystery. The questions What was the hole in Sinclair's mind? Why was Sheridan's destiny so important? What was the Vorlons' secret agenda? What were the Minbari hiding? continued to nag at the audience while events were building into something more significant. The audience was taken on a journey of discovery, learning about the world of Babylon 5, the new alien races not seen before, the characters that lived on the station, and the politics of Earth and the Psi Corps. By the fifth season, much of this material has been explored. The mysteries of the Vorlons and the Shadows are gone, and there is only their legacy to deal with. So something that to Byron and his telepaths is a revelation--that Vorlons created human telepaths--is already known to the audience.

Nonetheless, there is a new struggle to be faced by the members of the Interstellar Alliance, keeping the peace while suspicion and doubt threaten to destroy what they have worked for. Never has Babylon 5 been so much akin to the United Nations as here. The individual races have their own interests to think about, vying for power in a competitive galaxy, with Sheridan in the middle trying to hold it all together. So one attack here, another attack there, with a little misleading evidence to stir the pot, is exactly what is needed to bring the races into conflict. The fragile peace is on the verge of breaking up, barely a year after telling the Shadows and the Vorlons to get the hell out of our galaxy. It is all nicely plotted over several episodes, building small attacks that appear to be the work of Raiders into something more sinister, a concerted effort to destabilize the Alliance. But these maneuverings are not where the drama lies--the drama lies in how they affect the people caught up in them. Indeed, a

ny mystery about who is behind the attacks is deliberately removed by indicating to the audience early on that it is the Centauri. That is important because it focuses attention on Londo. We, as an audience, know exactly what is going on, while he can only suspect something is amiss. We watch helplessly as Londo becomes increasingly isolated by the other races, with evidence steadily mounting against his people. When he finally comes to realize the truth, it is too late to prevent his Homeworld from being bombed and himself from becoming the instrument of the Drakh.

These are the best moments in the season and there are many of them in the final clutch of episodes: Garibaldi's alcoholism being discovered, Delenn and Lennier facing death on a White Star, and the emergence of Lyta's extraordinary powers. They are the payoffs that simply wouldn't have been possible without the setup.

The gentler pace that pervades most of the season is a change in style for the show. J. Michael Straczynski, executive producer and the writer of all but one of the episodes this year, admits that this was his year to experiment. Episodes such as "A View from the Gallery" and sequences like Lyta and Byron making love certainly reflect that. The approach, although different from what has gone before, follows a pattern set up by the preceding seasons, each one with its own identity. Season One was more episodic, Season Two brought the arc into prominence, Season Three was Babylon 5 fighting back, and Season Four was fast. The tamer pace of Season Five allows the series to explore the consequences of the previous year and makes room for several stand-alone episodes. Some were more successful than others, with "A View from the Gallery," "The Very Long Night of Londo Mollari," and "Day of the Dead" ranking on most people's favorites list. Focusing on specific subsets of the B5 universe, "The Corps Is Mother, the C

orps Is Father" delves a little deeper into the Psi Corps, and "Learning Curve" takes the opportunity to look closer at Ranger training. "A View from the Gallery" is a refreshing episode from the point of view of two maintenance men who not only entertain with their engaging banter, but also provide time for reflection as one of them wonders what it might be like to pilot a Starfury in the heat of battle. "Day of the Dead" is both chilling and moving, giving Londo a final glimpse of happiness with the brief return of Adira and an emotional insight into Lochley's past.

It is the character stories that dominate the fifth year, and no two characters are more engaging than Londo and G'Kar. The history of conflict between their two peoples, their personal histories with each other, and the performances of Peter Jurasik and Andreas Katsulas always produce fireworks. They ended Season Four with a sense of reconciliation, sharing a joke together after Sheridan and Delenn's marriage, but not all issues between them had been resolved.

The issues begin to be addressed in the second episode, "The Very Long Night of Londo Mollari," when Londo, through a series of experiences that force him to face up to his own guilt, genuinely and sincerely apologizes to G'Kar. It clears the air between them, and although G'Kar is not quite prepared to forgive his former enemy, he is able to accept his apology. Their relationship becomes more easy from here on in, described quite succinctly by one of the maintenance men in "A View from the Gallery" as akin to that of a married couple. It is circumstances rather than choice or design that has brought them together, and the continual friction between them is both funny and sad. Peter Jurasik, who plays Londo, aptly describes them as the Odd Couple, bickering away with the banter of a well-rehearsed comedy partnership.

G'Kar becoming Londo's bodyguard keeps them together through some difficult times and allows the relationship to develop further. These two former enemies now have to rely on each other for safety in the Centauri palace. With the discovery of Na'Toth on Centauri Prime and Londo's help in rescuing her, Londo takes the first step toward redeeming himself in G'Kar's eyes. Then, finally, as his planet is being bombed, Londo risks himself to rescue G'Kar from his collapsing jail cell, and G'Kar is brought to a point where he can forgive him.

This final moment between these two is what the whole season had been building toward from their point of view and is one of the most powerful moments they have shared. It is their last good-bye, made all the stronger because of the history that both of them bring to this scene. And lying beneath it is the subtext of Londo's last moments as a free man. He cannot tell anyone, not even G'Kar, about the fate that awaits him. All he can do is hint, which only compounds the sadness for the character. He has done terrible things in a misguided attempt to see his people become powerful again. He has tried to redeem himself and now his greatest enemy is prepared to forgive him, but there is no escaping the consequences for Londo. He knows that he is descending down a dark road, he can see what awaits him at the end of it, yet he has no choice but to follow.

Londo's arc has been one of the strongest throughout the series, following his progression from the drinking, gambling clown he was at the beginning to the lonely emperor he becomes at the end. As the fifth season opens, he knows his destiny is to become emperor, but he cannot know the sorry circumstances that will lead him there. There is a moment of happiness for him in "Day of the Dead"--a night of passion and romance with Adira, and a reminder of what might have been had he taken a different path--but it is only a moment. Political movements take him back to Centauri Prime and a palace where a mad, bumbling regent sits on the throne, ready to kill, if necessary, with conspiracies flitting around the seat of power. It is all ugliness that stems from Londo and his earlier mistakes. Morden saw Londo as the right target for the Shadows to use to start a galactic conflict back in Season Two, and their influence still remains. The Drakh merely took over where their masters left off, controlling the regent with

a keeper attached to his neck, manipulating events to start another war, and ultimately controlling Londo. The scene of Londo sitting on the throne in the Centauri palace with all the trappings of the emperor, but totally alone and helpless to resist the Drakh, is the epitome of sadness for this character. It is a tragedy of one who was led astray, even though, in the end, he was the instrument of his own downfall.

One character who had to make an impact if she was to survive in the fifth season was Lochley. She had a hard act to follow, coming in as she did to replace Claudia Christian's Ivanova. The introduction of Lochley injected some needed conflict into the mix as the season opened. With other new plot lines needing time to establish themselves after the neat way Season Four had been wrapped up, Lochley helps beef up the early episodes by stirring up suspicion and doubt. The very fact that she is wearing an EarthForce uniform on a station that once declared independence from Earth sets her apart from the others. Her undeclared loyalties rile Garibaldi and produce some great fiery scenes between them. She is undoubtedly a tough, militaristic woman, who, it turns out, was on the "wrong" side during the civil war, but never do we really have cause to dislike her.

The credit for that must go to a combination of the writing and the acting. The writing introduces the suspicion and doubt from the other characters--capitalizing upon, rather than avoiding, a certain audience uneasiness at having to replace Ivanova--but never are we allowed to be carried along by it. Garibaldi is pretty isolated in his views, and although he may complain about her, he doesn't seem to have any real reason to do so. In fact, steadily and surely his doubts are proved wrong. The key scene for this is in "Learning Curve," when Garibaldi challenges Lochley about her loyalties and she admits she was on the other side in the fight against Earth. She gives such a spirited and ultimately reasonable speech about the ethics of being a soldier and it not being her place to tear up a constitution that she swore an oath to protect, that Garibaldi's position looks untenable. She even receives a round of applause from many in the mess hall, isolating his position even further. This conflict is finally resolv

ed after Garibaldi does some snooping in her private files and she is forced to admit that Sheridan trusts her implicitly because they were once married. It is worth noting that the performances go a long way toward selling this concept, with Lochley's rather embarrassed admission to Garibaldi and his amused reaction that results in the quip, "How many wives has he got?"

It is in this scene that we begin to see the softer side of Lochley. She admits to having made the mistake of falling in love with the wrong guy, and this serves to make her more human, more rounded, and a more likeable character. Although it has to be said that a lot of work in getting the audience to accept her had been done by this point. She stepped onboard with a workmanlike attitude and a determination, but also a smile. If the maintenance man's comment to Lochley in "A View from the Gallery," "You're okay in my book," was an attempt to convince the audience to accept Lochley, he was mostly preaching to the converted. However, getting the character accepted is not the only battle. There is also the challenge of doing something interesting with her, and the highlight for Lochley has to be "Day of the Dead." In the brief return of her friend, Zoe, Lochley has to confront her uncomfortable past that led to drug addiction, squalor, and almost death. It is a tremendously emotional episode for her.

After facing such opposition from Garibaldi when she first came onboard, it is ironic that Lochley is the one who becomes instrumental in making him face up to his alcoholism. Garibaldi has always been one of the most vibrant characters in the series. With a disreputable past, an often explosive personality, and a history of alcohol abuse, he is somewhat of a loose cannon. Garibaldi's arc in the fifth season exploits that and the philosophy of choices, consequences, and responsibilities that has dominated Babylon 5's storytelling since the first season.

It is significant that Garibaldi's first drink is not taken on the spur of the moment, but clearly after some consideration. He goes shopping, consciously buys a bottle of booze along with a loaf of bread and other provisions, then sits and contemplates his glass before downing it in one. Subconsciously he understands the consequences of returning to the bottle, something that rises to the surface in a stark dream sequence in "Darkness Ascending" in which he imagines himself responsible for the death of his friends and colleagues on a station ravaged by war. Like other hints of the future that have appeared in Babylon 5, it is a prophecy enacted by the rest of the season.

Slowly, steadily, Garibaldi's drinking affects one person after another. His long-term friend on the Drazi Homeworld is killed because alcohol kept him asleep when an assassin came to call. He turns up late and unprepared for meetings, and finally his inaction, brought on by drink, drags the whole Alliance into a potentially devastating war. He fails in his responsibilities and that has consequences not only for him, but for the people he cares about.

These consequences produce some charged moments for Garibaldi as he is gradually forced to face up to his own failures. In the early stages there are hints of remorse as he recounts his friend's death in "The Ragged Edge." Later, as the coherent mask he puts on for other people begins to break down, he exposes his weakness in front of a friend, Zack, and then inevitably in front of the Alliance security council. With his secret so undeniably laid bare, he faces the ultimate confrontation with Sheridan. What makes this scene so effective is that it is played on several levels, a moment that touches a range of emotions; anger, sympathy, sorrow, and friendship.

Once Garibaldi has admitted to his problem, the process of healing begins. With a helping hand from Lochley, he is shown that the support systems he needs to recover were always around him. He has Lise, his friends, and a new life waiting for him on Mars. His desperation was understandable, frustrated at not being able to avenge what Bester did to him, put into a position where he was beaten up and almost shot by rogue telepaths, but the bottle was never the answer.

The story arc for Lennier in the fifth season takes him far away from his beginnings as a sheltered graduate of a Minbari temple and confronts his very private feelings for Delenn. His need to join the Rangers, his dedication to his mission, and his final betrayal of Sheridan all stem from his love for the woman he cannot have. Unable to be around her while she is happily married to another, he leaves Babylon 5 and throws himself wholeheartedly into his Ranger training. When she sends him on an important mission, he responds with equal determination, risking his life for the cause because it is so important to her and because she was the one who asked him. All the while, the subtext of his love remains. His final, fatal moment of weakness in which he decides to let Sheridan die after being such a loyal, faithful, and conscientious companion to Delenn is anguishing to watch. But the groundwork had been carefully laid down. His love for Delenn had, if anything, become stronger since his surprise confession to Marcus back in Season Three. It moved to the surface in his emotional farewell to Delenn before leaving for the Rangers and in his vain hope in "Meditations on the Abyss" that Delenn wants to meet him in Down Below for a clandestine romance rather than to send him on a mission. Morden warns him in "Day of the Dead" that he will betray the Anla'shok, and ten episodes later that is exactly what he does. Lennier later explains it was something that "just happened," a moment born out of emotion, not rationality. Wracked with shame and guilt, he takes off into the galaxy alone.

The season ends by scattering the characters to the four winds, in part to set up possible future adventures for Crusade and the other planned follow-up projects, and in part to show that the process of growth and change continues. It is a bittersweet ending that brings the characters to rest, but does not ensure a happy resolution for them all. Garibaldi seems to have finally left his problems behind him, Franklin is given a promotion and the chance to follow his interest in xenobiology on Earth, G'Kar and Lyta are setting off on unknown adventures, and Babylon 5 is left in the capable hands of the supporting cast. But Sheridan and Delenn's journey to Minbar to find wedded bliss is overshadowed by Lennier's actions, Londo faces the prospect of growing old alone as the Centauri emperor, and the Drakh are still waiting in the wings to strike at Sheridan's son when he comes of age.

The story concludes with "Sleeping in Light," the finale filmed the previous year. Although it is strange to see Ivanova back, it is difficult to imagine a more fitting end to such a landmark series. It is a mostly happy end for those that survived and an uplifting conclusion to their five-year struggle. The emotion is at its height as Sheridan says his final farewells to Delenn, his friends and colleagues, and the Babylon 5 station, itself. At the end his death evokes a sense of wonder as he journeys beyond the Rim.

The fifth season was a difficult year for Babylon 5. Its challenge was to prove to skeptics that there was more story to tell following the events of the first four years. It was a challenge that the series met head-on, and as a result, Babylon 5 remains one of the best examples of science fiction to have been made for television.

When Babylon 5 began, in 1992, many claimed that the series was destined to fail, Babylon 5 creator J. Michael Straczynski recalls. "The odds against us were considerable. I was saying, 'This is going to be a five-year show, period.' They would say, 'What makes you think you will get five years out of this?' [I'd reply] 'We're on a mission from God, okay?'" [Starburst, special 35]

The very achievement of making the show last its full, planned five years has been incredibly important for the people who lived through it. Few shows make it that far--and Babylon 5 nearly didn't. The threat of cancellation was always hanging over it and nearly destroyed it altogether at the end of the fourth year. It was only pulled back from the brink by a change of network, from Warner Bros.' PTEN consortium to cable channel TNT when the former network collapsed. But the commercial success that kept producers, cast, and crew employed for five years is only a side issue in Babylon 5's achievement. Its main success has been fulfilling the story plan that lay at the heart of the show, its famous "five-year arc."

The phrase "five-year arc" has become so synonymous with the show that it tends to get trotted out in a blase fashion. But back in 1992, this was a new concept. Some shows, particularly soap operas, used continuous story lines that progressed with each episode and were often planned as much as two years ahead. But no one had attempted a story on such a grand scale, where the plot points introduced in the beginning would continue to play a significant part throughout the show's entire length until it reached a predetermined conclusion. Television is a fickle business where shows can be canceled on a whim without warning, leaving the rest of the story untold. Television audiences themselves can be fickle, flitting from channel to channel, picking up on a program halfway into its season or missing the odd episode, and so finding it difficult to follow an ongoing story. Then there are production considerations, like the risk the story line is going to be wrecked by the lead actor getting run over by a bus or the producers wanting to change direction after judging the response of the audience. But Joe Straczynski had worked out his story in such detail that he had faith it could work, and with his famous "trap doors" for every character, he could keep his story on track no matter what production considerations intervened. No one actually had an unpleasant encounter with a bus, thankfully, but when there was a need to replace Sinclair with Sheridan, and when the actress playing Talia Winters (Andrea Thompson) wanted to leave to pursue other work, the trap doors came into play and the story continued because it was the story that was important.

And it was the story that excited audiences. The idea of a story arc that lasted five years may have sounded daunting to the television industry, but it hooked viewers in a way that few television programs ever achieve. "We were able to tell a story over five years where things were foreshadowed in year one and it paid off in year three, in a medium where often you set things up in the teaser and pay it off two acts later," Joe says. "We extended it by years and the audience follows it and gets it ... We can say to the television community, 'You're wrong--the viewers are not morons, they're sharp people. If you would teach them and talk to them in a straightforward fashion they will react and come to you.' And they have done that." [Cult Times, issue 31]

This fresh approach to storytelling kept people talking about Babylon 5 down at the pub, over the phone, and on the Internet. Speculation about what was going to happen next, what was the meaning of a certain line of dialogue or a certain scene became more profound precisely because it was all planned out ahead of time. Viewers developed their own theories about everything: What was Kosh hiding under his encounter suit? Could he be an angel? How did he know so much about the future? Could it be that the Vorlons age backwards? Is his apparently benevolent nature hiding his true dark side? It was a series that got people involved, made them think, and kept them coming back week after week for the next installment. It was an intricate story in which every detail could have significance, where watching and rewatching the episodes could provide new insight. "We proved we were right, right on the production, right on the story," Joe says. "They said it would never work. Now, of course, Dark Skies said they had a five-year arc, the new Roddenberry show [Earth: Final Conflict] has a five-year arc--this term has now entered the vernacular. We have created something new. That's a good thing." [Cult Times, issue 31]

What was also new for science fiction television was Babylon 5's nod of respect to the tradition of the written genre. For a long time, even into the nineties, science fiction television was regarded as something for kids. It was about rockets, robots, and ray guns, people with silly costumes and annoying whizkids. That's not to denigrate the many excellent series that preceded Babylon 5--indeed, some of them such as Blake's 7 directly influenced it--but that perception continued to exist and be reflected in some of the shows getting on the air. Babylon 5 broke through that barrier and tapped into an audience that had been brought up on written science fiction. The aliens were real aliens. They may have been limited by the practicalities of a television show in that they had to be played by a human actor--although Kosh was an acknowledgment of that restriction, with his true form hidden under the encounter suit--but they were three-dimensional, with a culture and a philosophy all their own. They walked onto Babylon 5 with a fully sketched background that gave them a depth and a believability rare in science fiction television. The aliens are not simply a metaphor for a part of human nature--e.g., a "warrior race"--but complex peoples with different facets that are gradually revealed. Moreover, the individuals of these alien races have their own personalities, so both G'Kar and Na'Toth are decisively Narn in the way they behave, but are also characters in their own right.

It is clear that the people behind the show understand science fiction. Not only does Babylon 5 get the terminology right--even Star Wars thought a parsec was a length of time, when it's actually a measurement of distance--it also has respect for the concepts that have developed within the genre over the years. In other shows, telepaths tend to be people who can do clever things with their minds, but in Babylon 5, the implications of what it might mean to be telepathic, both to the individual and society, are taken into account. This is a testament partly to the amount of thought put into the framework of Babylon 5 and partly to the tradition of science fiction literature. The Psi Cop played by Walter Koenig is even named in tribute to Alfred Bester, the author of the seminal telepath novel The Demolished Man.

Some of the key people on the show, including Joe Straczynski and producer John Copeland, were fans before they were ever television producers, and it is an enthusiasm that can be seen on the screen. "We brought that passion, our passion for man's exploration of space, our imaginations that were stretched by reading science fiction and fantasy growing up, here to this show," John says. "I know Joe is an avid reader and I think that all translated into this show. This is a thinking person's show, this is a smart show. This is a show that deals with the types of material and things that you normally encounter in books, and that's not the case with most science fiction which is on television, or has been on television, or has been in the movie theater. A lot of them are just shoot-'em-up action adventure stories. I think that folks that read science fiction tend to be brighter, are more thoughtful about things, and you have to deliver that to them if you want them to buy into your show. It has to be a smart and interesting and intelligent show, and I think we've tried to do that here."

The intelligence lies in the nature of the story. Science fiction has often been described as a genre of ideas, and Babylon 5 always delivered compelling ideas, whether they were in the truth about the Vorlons and/or in Sinclair's destiny to become Valen. They stretched the mind and resonated in today's world. If Babylon 5 has achieved its aim in telling a great story, then it has also said something to its audience along the way. Joe Straczynski said he wanted to show that choices have consequences that bring responsibilities, and that theme is explored over and over again. The most demonstrative example of this is probably Londo's story. He hoped his alliance with the Shadows would return the Centauri to greatness, but it only took them into a war that threatened his Homeworld and eventually pulled Londo down with it, to face his responsibility as an aging, ailing emperor of a ravaged people. If you want to sit back and enjoy the adventure, that is fine, but if you want to look deeper there are other issues to consider.

One of the things that science fiction does so well is comment on the present day at one remove, whether that comment be about racism and the benefits of working together, or about the realities of war. It also shows there are no easy answers. Where a traditional television episode might end on a moral high note with a pat answer to a problem, Babylon 5 presents an issue in shades of grey, where there is not always a right answer. One early example is Season One's "Believers," where Franklin must decide whether to save a child against his religious beliefs or let him die. "That's the wonderful thing about doing a story that is set in the future," John Copeland says. "That is something that is done again and again in great works of science fiction. They pose the same moral dilemmas and deal with issues that you're able to look at from a different perspective and it's not sucked into your culture with your nationality wrapped around it. In some ways they [the stories] are extremely moral and other ways they are frustratingly amoral because they become much more like life that way. It's not 'good' or 'bad,' it's grey, and endings don't always necessarily become happy endings, they're just endings. It's like everybody wants to have a happy life--well, you don't, you just have a life."

Babylon 5 has never been afraid to reach a new level of storytelling, whether by breaking the simplistic view that the villains are always the villains and the good guys are always straight or true, or by the unconventional use of flash-forwards. Babylon 5 has been bold and brave with its storytelling, and if one or two elements failed to hit their mark, they are far overshadowed by its successes. The old adage that a story must have a beginning, a middle, and an end, but not necessarily in that order, certainly applies here. In the early days when the show was working hard to set up its complex world, there were hints and visions--"Signs and Portents"--of the great arc that was developing in the background. Later, when the elements of the story were coming together, hints of the future served to intensify the arc. The supreme example of this is "War without End," when Sheridan is thrust forward in time to Centauri Prime where he is a prisoner and Londo is emperor of the devastated planet. Suddenly a whole new set of questions is displayed before the audience.

And then there are the characters. Perhaps it is obvious to say that a drama without good characterization is not dramatic at all, but that has been a flaw of many a science fiction project and television adventure show in the past. In Babylon 5, the people are just as important as the plot--they are affected by the plot, and the plot affects them, until the two are so interwoven that one is part of the other. Each person is vividly drawn, from Londo's characteristic quirk of turning a statement into a rhetorical question--as in, "your recent alliance with Mr. Morden, yes?" to Refa in "Ceremonies of Light and Dark"--to Garibaldi's troubled, alcoholic past. The characters also progress in a way that is rare in television. In a normal episodic television show, where the characters begin at the start of the episode is where they have to end at the end of it. The whole format of an episodic show, designed to appeal to the casual viewer, dictates that to be the case. But with Babylon 5, the arc of the show is also the arc of the characters. They progress, they learn, and they are affected by what happens around them. Two characters, Delenn and Sinclair, even change species! It is the essence of storytelling for novels, plays, and films, but has never traditionally been the resolve of television. The characters in Babylon 5 are vivid, complex, and encourage the audience to take the journey with them. Without such effective characterization, the show would lack much of the depth that is its hallmark.

Babylon 5 has become a landmark in science fiction television, through its approach to both story and production. It was one of the main players in the science fiction boom of the mid-1990s and proved that there was a market out there for intelligent science fiction. For John Copeland, who had spent years trying to sell different science fiction shows to TV networks with fellow producer Douglas Netter, it has been a truly satisfying experience. "What Babylon 5 achieved is to really put a point on the end of the sentence that there is an audience worldwide for science fiction television programming that is not Star Trek," he says. "For the longest time they all thought in the executive suites that Star Trek was its own unique phenomenon. I think as a result of B5 coming on the air, it has made it possible for shows like Space: Above and Beyond and for things like Sliders. We've helped pave the way, along with The X-Files."

Babylon 5's use of special effects has been another one of its achievements. One of the reasons why television networks were skeptical of putting money into science fiction was that they knew how expensive it was to generate special effects. Babylon 5 came in with a new approach, using computer graphics (CGI). It was uncharted territory, and even the man who spearheaded B5's CGI look, Ron Thornton, secretly wasn't entirely sure how he was going to do it. But the result gave a unique look to the series, and the new technique enabled them to do the sort of shots that would have been impossible with traditional model work. Now everyone's doing it. "The thing that has been done with Babylon 5 is to say that you can look at new ways of doing things and be successful," John Copeland says. "There were many people who said, 'Oh you're going to do all computer effects and it's not going to work, it's going to be terrible.' Now you look at Space: Above and Beyond, which came along two years after us, and they tried to go down the exact same road as we did with all digital effects. I think we have shown that these technologies are embraceable for television, that you can manage them within the restraints of a television budget and within a television schedule."

But, in the end, the success of Babylon 5 will be measured by the story it told. "I wanted to create a myth for television on the scale of the Lord of the Rings books or the Foundation books," Joe Straczynski says, and after five years, that was what he had done. It was a large-canvas story that looked back as far as the first sentient beings in the galaxy, followed mankind into a new age, and looked forward to the destruction of the Earth and humanity's transition into a higher form. It spanned alien races with different philosophies, different cultures, and different faces. It saw characters die, be resurrected, fall in love, be betrayed, and fulfill their destiny. The story gave us the Babylon 5 station, which began as our last, best hope for peace; became our last, best hope for victory; then rose from the ashes of a war to head the push for stability and a new Interstellar Alliance. It is a story that is not entirely over because there will be spinoffs, but it is a story that has been concluded. Perhaps one should leave the last word to its creator, J. Michael Straczynski.

After completing the final-ever episode of Babylon 5, "Sleeping in Light," he told fans: "I think ... people will look back at the whole story, through all these long years and say 'It was a good story' and close the cover and put it on the shelf with the other books ... and turn off the lights and go to bed feeling that the time was well spent. Which is the most any writer can ever ask for. To tell a tale worth telling, to make people cry, to make people laugh. And even, once in a while, make them think about things and see the world just a little differently than when they began.

"Everything I set out to say, I said. I've carried this story like a hermit crab carries its shell for six long years, counting the pilot. It's been an awfully long and difficult road, and no one will ever really know just how hard the show was to make. Nor should they, because it isn't the difficulty that makes the story, the story makes the story. But one way or another ... when it airs, the burden is off at last. Then it no longer belongs to me. It belongs to you. As it should be. And, in the end, I think you'll be pleased."

"It's these people. I've worked with them a long time, they're like your family and you see them all the time, and that will be the hardest stuff to leave behind. I won't miss Londo, Londo got to play it out, he found his way to the throne, but I will miss the people."

--Peter Jurasik, Londo

"I've experienced tremendous growth as an actor. I don't even think you can find that in the theater because you never stay with a character long enough. A play is only two hours, but we've had one hundred and ten hours--what a chance to really get into a character and take it through every situation, every twist and turn. So I am just totally grateful for this experience."

--Andreas Katsulas, G'Kar

"I think in the long run Babylon 5 will be looked at and remembered as one of the very best--if not the best--television science fiction series ever made. I'm very proud to be a part of it."

--Bill Mumy, Lennier

"When I first came on the show I had three lines and I turned down two other jobs to do the show because I just really wanted to do it. It was like walking into a comic book. That whole first year was kind of like a mystical experience for me. Every time they called me to come to work, I'd get so thrilled and excited, and I'd turn down other work at times to do the show. This is so much fun to put on this uniform and be a space cop. Man, this is like a dream come true!"

--Jeff Conaway, Zack

"Most important of all has been making friends; good, long-term, solid friends. I love coming to work every day. We have a really close group here and even though we all got into it knowing it was a five-year arc, it's still very sad to see a family break up. No matter where I go I'm always going to take the energy and enthusiasm and the camaraderie of this set with me."

--Jerry Doyle, Garibaldi

"It's been an incredible journey. In Blackpool they've got this big old roller coaster and everyone had to ride it. When you come off, you encourage all your friends 'You gotta go ride the big one.' Babylon 5's the big one and everyone's been telling their friends 'You gotta watch it,' so slowly but surely we're gaining popularity. It's been an amazing ride."

--Patricia Tallman, Lyta

"I think I'll remember the five years I was on Babylon 5 as being part of a phenomenon, of a science fiction chapter that will go down as, I think, a positive addition to the science fiction television genre. I am lucky enough and fortunate enough to be part of that, and that brings a smile to my face."

--Richard Biggs, Franklin

"I get very attached to my job and my work and I'm sad that it's ending. The highlights for me are, number one, getting the chance to direct, number two, to be involved in such a wonderfully rich show, and number three, making friends."

--Stephen Furst, Vir

"It's been a wonderful experience for me. Joe wrote beautiful stuff for me that really touched me and moved me and had so much to do with my own experience. I agree with him so much, and sometimes I think he wrote it exclusively for me."

--Mira Furlan, Delenn

"This has been the greatest. I am very sad that it's over. I'm very proud to have been on it. This was a great place, a great bunch of people to work with, and you don't get that very often. In my twenty-seven years as a professional actor, this is one of the good ones that I will remember."

--Bruce Boxleitner, Sheridan

Babylon 5's Fifth Season

It had been a hard struggle to get a commission for a fifth and final season of Babylon 5. The previous year had been full of uncertainties, with the prospect of cancellation looming so large that portions of the story were slipped into the fourth season to bring the series to a satisfactory conclusion. It was a wise move, had Warner Bros. declared themselves unwilling to stump up the money for more episodes. With the collapse of PTEN, the show had to find a new venue to survive. U.S. cable channel TNT eventually came through at the eleventh hour, having previously obtained the rights to show the first four seasons. This secured a dedicated home for the show and greater exposure in its home country. But after the celebrations died down, one question remained: With some elements of the story moved up into the fourth year, could there really be more story to tell?

The creative force behind the series, writer and executive producer J. Michael Straczynski, had prepared for this moment. In squeezing what story he could into the fourth year, he always knew it was possible that the powers that be would come to their senses and let him have the fifth season he so desired. The remaining story elements planned for Season Five were still untouched. Most obviously, these included the increasing tensions between telepaths and normals--or "mundanes" as they increasingly became known during the fifth season--set up during the preceding seasons, the creation of the new Interstellar Alliance, and Londo's final descent into darkness. After Season Four's frantic pace, the hope was that Season Five was going to be slower and more reflective.

The main arcs for Season Five are the telepath struggle, Londo's rise to power, the bumpy first year of Sheridan's presidency, and the Drakh war. The trouble between telepaths and normals had been building for some time--Lyta had predicted it back in Season Four, and "The Deconstruction of Falling Stars" confirmed that one day there would be a war between telepaths and normals. It is a powder keg waiting to explode, and the spark arrives on Babylon 5 in the shape of Byron. He, himself, is a nonviolent, almost religious figure, but the tension between the two species of humanity is too much to contain even for him. Normals fear telepaths, a fear that has traditionally been tempered by forcing them to join the Psi Corps where they are bound by rules that protect the ordinary citizen. But rogues present a different face: a group of people with extra powers, free to use those powers at their whim. The response to Byron and his followers is inevitable.

This is the type of situation Babylon 5 handles so well, a dilemma where there is no black and white, and no clear solution that can produce a happy ending for all sides. The Psi Corps, as we have seen, can be an oppressive organization and the rogues only want a place to stay and hide from repression. Making a home on Babylon 5 is not easy, and they are immediately confronted with ignorance and prejudice from the bully boys--or "bad guy types," as the scripts often refer to them--in Down Below. In such circumstances, who could fail to sympathize with the rogues, especially when they have such a charismatic, eloquent leader as Byron? He may borrow some of his nice words from the great writers of history, but the words are powerful, enough to command loyalty from the others and draw in Lyta.

Lyta has come to the stage where she has closed herself off to emotion. She risked herself to try to find Sheridan when he fell at Z'ha'dum, she was an important asset during the Shadow War and instrumental in the final battle in Earth's civil war, but still she found little comfort in the nontelepaths she helped. She was forced back into the Psi Corps to survive, and it is not surprising that she tells Byron, "I don't let anybody in anymore." But gradually she's drawn to his charm, finding hope in his philosophy and love for someone who truly cares for her, not for her powers. Finally, she is able to let someone in, in the most intimate way possible, not only sharing her body with him, but also taking down the barriers in her mind, opening a window to the secrets she had been hiding. This sex scene is one of the most enduring images of the season and something uncharacteristic for Babylon 5. It reveals to Byron and his followers that the Vorlons were responsible for creating telepaths and sets the scene for confrontation and tragedy.

Byron has good reason to ask for a Homeworld for telepaths and, on the surface, it would seem to be an acceptable solution to the tensions that have grown up between telepaths and normals. But there is a fatal flaw in his argument. He sincerely believes that telepaths are better than normals, that violence is not their way. But the truth is that evolution may have given them extra talents, but it has not divorced them from human nature. Desperation leads a group of them to respond to their human instincts and turn to violence. From that moment, Byron's cause is doomed. Captain Lochley, left with a hostage situation on her hands, does the only thing she can do to stop the station being held to ransom by terrorists--she calls in Bester and the Psi Cops. It brings the situation to an ugly end. Byron destroys himself, putting an end to the trouble for the moment, but ensuring that his name and his cause live on. He, as Zack predicted the moment he stepped onto the station, has become a martyr. And there Babylon 5 leaves the telepath situation. Its influence lives on, of course, in Lyta, in her hardened determination to achieve a Homeworld for her people.

Then comes the Drakh war--not so much a war; more of a diplomatic crisis for the new Interstellar Alliance, driven by a series of terrorist-like attacks. The characteristic way Babylon 5 builds seemingly small incidents into something potentially devastating is equally effective here. The end of the fourth season left the audience with a sense of closure, and although some matters were left unresolved, it was a satisfactory ending. In bringing the story back up to speed again and introducing new threads, Babylon 5 asks the audience to be patient.

This same trick was used in the first and second seasons, where the series was starting with a blank slate. All was discovery and mystery. The questions What was the hole in Sinclair's mind? Why was Sheridan's destiny so important? What was the Vorlons' secret agenda? What were the Minbari hiding? continued to nag at the audience while events were building into something more significant. The audience was taken on a journey of discovery, learning about the world of Babylon 5, the new alien races not seen before, the characters that lived on the station, and the politics of Earth and the Psi Corps. By the fifth season, much of this material has been explored. The mysteries of the Vorlons and the Shadows are gone, and there is only their legacy to deal with. So something that to Byron and his telepaths is a revelation--that Vorlons created human telepaths--is already known to the audience.

Nonetheless, there is a new struggle to be faced by the members of the Interstellar Alliance, keeping the peace while suspicion and doubt threaten to destroy what they have worked for. Never has Babylon 5 been so much akin to the United Nations as here. The individual races have their own interests to think about, vying for power in a competitive galaxy, with Sheridan in the middle trying to hold it all together. So one attack here, another attack there, with a little misleading evidence to stir the pot, is exactly what is needed to bring the races into conflict. The fragile peace is on the verge of breaking up, barely a year after telling the Shadows and the Vorlons to get the hell out of our galaxy. It is all nicely plotted over several episodes, building small attacks that appear to be the work of Raiders into something more sinister, a concerted effort to destabilize the Alliance. But these maneuverings are not where the drama lies--the drama lies in how they affect the people caught up in them. Indeed, a

ny mystery about who is behind the attacks is deliberately removed by indicating to the audience early on that it is the Centauri. That is important because it focuses attention on Londo. We, as an audience, know exactly what is going on, while he can only suspect something is amiss. We watch helplessly as Londo becomes increasingly isolated by the other races, with evidence steadily mounting against his people. When he finally comes to realize the truth, it is too late to prevent his Homeworld from being bombed and himself from becoming the instrument of the Drakh.

These are the best moments in the season and there are many of them in the final clutch of episodes: Garibaldi's alcoholism being discovered, Delenn and Lennier facing death on a White Star, and the emergence of Lyta's extraordinary powers. They are the payoffs that simply wouldn't have been possible without the setup.

The gentler pace that pervades most of the season is a change in style for the show. J. Michael Straczynski, executive producer and the writer of all but one of the episodes this year, admits that this was his year to experiment. Episodes such as "A View from the Gallery" and sequences like Lyta and Byron making love certainly reflect that. The approach, although different from what has gone before, follows a pattern set up by the preceding seasons, each one with its own identity. Season One was more episodic, Season Two brought the arc into prominence, Season Three was Babylon 5 fighting back, and Season Four was fast. The tamer pace of Season Five allows the series to explore the consequences of the previous year and makes room for several stand-alone episodes. Some were more successful than others, with "A View from the Gallery," "The Very Long Night of Londo Mollari," and "Day of the Dead" ranking on most people's favorites list. Focusing on specific subsets of the B5 universe, "The Corps Is Mother, the C

orps Is Father" delves a little deeper into the Psi Corps, and "Learning Curve" takes the opportunity to look closer at Ranger training. "A View from the Gallery" is a refreshing episode from the point of view of two maintenance men who not only entertain with their engaging banter, but also provide time for reflection as one of them wonders what it might be like to pilot a Starfury in the heat of battle. "Day of the Dead" is both chilling and moving, giving Londo a final glimpse of happiness with the brief return of Adira and an emotional insight into Lochley's past.

It is the character stories that dominate the fifth year, and no two characters are more engaging than Londo and G'Kar. The history of conflict between their two peoples, their personal histories with each other, and the performances of Peter Jurasik and Andreas Katsulas always produce fireworks. They ended Season Four with a sense of reconciliation, sharing a joke together after Sheridan and Delenn's marriage, but not all issues between them had been resolved.