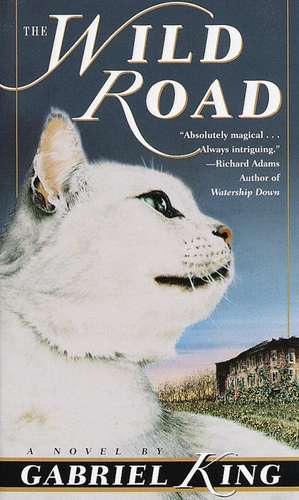

The Wild Road

Autor Gabriel Kingen Limba Engleză Paperback – 28 feb 1999

Secure in a world of privilege and comfort, the kitten Tag is happy as a pampered house pet--until the dreams come. Dreams that pour into his safe, snug world from the wise old cat Majicou: hazy images of travel along the magical highways of the animals, of a mission, and of a terrible responsibility that will fall on young Tag. Armed with the cryptic message that he must bring the King and Queen of cats to Tintagel before the spring equinox, Tag ventures outside. Meanwhile, an evil human known only as the Alchemist doggedly hunts the Queen for his own ghastly ends. And if the Alchemist captures her, the world will never be safe again . . .

Preț: 56.00 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 84

Preț estimativ în valută:

10.72€ • 11.64$ • 9.00£

10.72€ • 11.64$ • 9.00£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 01-15 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780345423030

ISBN-10: 0345423038

Pagini: 480

Dimensiuni: 110 x 178 x 27 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Del Rey Books

ISBN-10: 0345423038

Pagini: 480

Dimensiuni: 110 x 178 x 27 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Del Rey Books

Notă biografică

A lifelong cat lover, Gabriel King has shared a home with every variety of feline, from stray to pedigree. He lives in London.

Extras

Among human beings a cat is merely a cat; among cats a cat is a

prowling shadow in a jungle.

--Karel Capek

They called the kitten Tag. They fed him, and he grew. They put a collar

around his neck. They entertained him, and the world began to take on

shape.

It was his world, full of novelty yet always reliable, exciting yet

secure. He was a small king; and by the time a week was out, he had

explored every inch of his new kingdom. He liked the kitchen best. It was

warm in there on a cold day, and from the windowsill he could see out into

the garden. In the kitchen they made food, which was easy to get off them.

He had bowls of his own to eat it from. He had a box of clean dirt to

scrat in. The kitchen wasn't entirely comfortable--especially in the

morning, when things went off or went around very loudly without

warning--but elsewhere they had given him a large sofa, covered in dark red

velvet, among the scattered cushions of which he scrabbled and burrowed

and slept. He had brass tubs with plants and some very interesting

fireplaces full of dried flowers, out of which flowed odors damp and sooty.

Up a flight of stairs and into every room, every cupboard and corner! It

was big up there, and full of unattended human things. At first he

wouldn't go on his own but always made one of them accompany him while he

inspected the shelves stuffed with clean linen and dusty books.

"Come on, come on!" he urged them. "Here now! Look, here!" They never

answered.

They were too dull.

A further flight up, and it was as if nobody had ever lived there--echoes

on the uncarpeted stairs, gray floorboards and open doors, pale bright

light pouring in through uncurtained windows. Up there, each bare floor

had a smell of its own; each ball of fluff had a personality. If he

listened, he could hear dead spiders contracting behind the woodwork. Left

to himself up there he danced, for reasons he barely understood. It was a

territorial dance, grave yet full of energy. Simply to occupy the space,

perhaps, he leapt and pounced and hurled himself about, then slept in a

pool of sunshine as if someone had switched him off. When he woke, the sun

had moved away, and they were calling him to come and eat more new things.

They called him Tag. He called them dull.

"Come on, dulls!" he urged them. "Come on!"

They had a room where they poured water on themselves. Every morning he

hid outside it and jumped out on the big dull bare feet that passed. Nice

but dull, they were never quick enough or nimble enough to avoid him. They

never learned. They remained shadowy to him--a large smell, cheerful if

meaningless goings-on, a caring face suspended over him like the moon

through the window if he woke afraid. They remained patient, amiable,

easily convinced, less focused than a tin of meat-and-liver dinner. The

dulls were for food or comfort or play. Especially for play. One of his

earliest memories was of chasing soap bubbles. The light of an autumn

evening shifted gently from blue to a deep orange. Up and down the room

rushed Tag, clapping his front paws in the air. He loved the movement. He

loved the heavy warmth of the air. Everything was exciting. Everything was

golden. The iridescence of each bubble was a brand-new world, a brand-new

opportunity. It was like waking up in the morning.

Bubble! Tag thought. Another bubble!

He thought, Chase the bubbles!

As leggy and unsteady, as easily surprised, as easy to tease, as full of

daft energy as every kitten, Tag pursued the bubbles, and the bubbles--each

with its tiny reflected picture of the room in strange, slippery

colors--evaded him smoothly and neatly and then hid among a sheaf of dried

flowers or floated slowly up the chimney or blundered without a care into

a piece of furniture and burst. He heard them burst, in a way a human

being never could, with a sound like tapped porcelain.

Evanescence and infinite renewal!

Any cat who wants to live forever should watch bubbles. Only kittens

should chase them.

Tag would chase anything. But the toy he enjoyed most was a small cloth

mouse with a very energetic odor. It had been bright red to start with.

Now it was rather dirty, and to its original smell had been added that of

floor polish. Tag whacked it around the shiny living room floor. Off it

skidded. Tag skidded after it, scrabbling to keep upright on the tighter

turns.

One day he found a real mouse hiding under the Welsh dresser.

A real mouse was a different thing.

Tag could see it, a little pointed black shape against the gray dimness.

He could smell it too, sharp and terrified against the customary smell of

fluff balls and seasoned pine. It knew he was there! It kept very still,

but there was a lick of light off one beady eye, and he could feel the

thoughts racing and racing through its tiny head. All the mouse's fear was

trapped there under the dresser, stretched taut between the two of them

like a wire. Tag vibrated with it. He wanted to chase and pounce. He

wanted to eat the mouse: he didn't want to eat it. He felt powerful and

predatory; he felt bigger than himself. At the same time he was anxious

and frightened--for himself and the mouse. Eating someone was such a big

step. He rather regretted his bravado with the pet shop finches.

He watched the mouse for some time. It watched him. Suddenly, Tag decided

not to change either of their lives. His old cloth mouse had a nicer smell

anyway. He reached in expertly, hooked it out, and walked away with it in

his jaws. "Got you!" he told it. He flung it in the air and caught it.

After a few minutes he had forgotten the real mouse, though it probably

never forgot him--and his dreams were never the same.

That afternoon he took the cloth mouse with him up to the third floor

where he could pat it about in a drench of cool light.

When he got bored with this he jumped up on the windowsill. From up there

he had a view of the gardens stretching away right and left between the

houses. However much he cajoled or bullied them, the dulls never seemed to

understand that he wanted to go out there. It fascinated him. His own

garden had a lawn full of moss and clover that sloped down toward the

house, where a steep rockery gave way to the lichen-stained tiles of the

checkerboard patio. Lime trees overhung the back fence, along which--almost

obscured by colonies of cotoneaster, monbretia, and fuchsia--ran a dark,

narrow path of crazy paving. Cool smells came up from the garden after

rain. Wood pigeons shifted furtively in the branches all endless sunny

afternoon, then burst into loud, aimless cooing. At twilight, the sleepy

liquid call of blackbird and thrush seemed to come from another world; and

the greens of the lawn looked mysterious and unreal. Dawn filled the trees

with squirrels, who chased one another from branch to branch, looting as

they went, while birds quartered the lawn or hopped in circles around the

mossy stone birdbath.

Transfixed with excitement, Tag watched them pull up worms.

That afternoon, a magpie was in blatant possession of the lawn, strutting

around the birdbath and every so often emitting loud and raucous cries. It

was a big, glossy bird, proud of its elegant black-and-white livery and

metallic blue flashes. Tag had seen it before. He hated its bobbing head

and powerful, ugly beak. He hated its flat, ironic eyes. Most of all he

hated the way it seemed to look directly up at him, as if to say, My lawn!

Tag narrowed his eyes. Angry chattering sounds he couldn't control came

from his throat. He jumped off the windowsill, then back up again.

"Wrong!" he said. "Wrong!"

But the bird pretended not to hear him--though he was certain it could--and

unable to bear its smug proprietorial air, Tag sat down, curled his tail

around himself, and closed his eyes. After a while, he fell asleep,

thinking confusedly, My mouse. This seemed to lead him into a dream.

He dreamed that he was under the Welsh dresser, eating something. Somehow,

the dark gap beneath the dresser was big enough for him to enter; he had

followed something in there, and was eating it. The soft parts had a warm,

acrid, salty taste, and he could hardly get them down fast enough. Before

he was able to swallow the tougher bits he had to shear them with the

carnassial teeth at the side of his jaw, breathing heavily through his

mouth as he did so. That was enjoyable too. Just as he was finishing

off--licking his lips, snuffing the dusty floor where it had been in case

he had missed anything--he heard a voice in the dark whisper quite close to

him, "Tag is not your true name."

He whirled around. Nothing. Yet someone was there under the dresser with

him. He could almost feel the heat of its body, the smell of its breath,

the unsettling companionable feel of it. It had quietly watched him eat

and said nothing. Now he felt guilty, angry, afraid. His fur bristled. He

tried to back out from under the dresser, but now everything was the right

size again and he was stuck, squeezed down tight in a dark space that

smelled of wood and dust and blood with a creature he couldn't see. "Tag,"

it whispered. "Listen. Tag is not your true name." He felt that if he

stayed there any longer, it would push its face right into his, touch him

in the dark, tell him something he didn't want to hear ...

"Tag is my name!" he cried, and woke up--to a loud, rapid hammering noise

near his ear. While he slept, the magpie had flown up from the garden. It

was strutting to and fro on the ledge directly outside the window,

screeching and cawing, flapping its wings against the glass, filling the

whole world with its clamor. Now its face was right next to his, and its

chipped, wicked beak was drumming against the glass and it was shouting at

him.

"Call yourself a cat? Call yourself a cat?"

And he fell off the windowsill and hit his head hard on the floor.

Everything went a soft dark brown color, like comforting fur. When he woke

up again, the bird was gone and he could hear the dulls preparing their

food downstairs, and he thought it had all been the same dream.

Tag had lived in the house for two months. It seemed much longer, a great

stretch of time in which he was never unhappy. He never wanted for

anything. He doubled in size. His sleep was sound, his dreams infrequent

and full of kitten things. All that seemed to be changing. Now, as he

curled up on the velvet sofa, he wondered what would happen when he closed

his eyes. Each time he slept, he lived another life--or fragments of it, a

life of which he had no understanding.

In one dream he was walking beneath a sliver of yellow moon, with ragged

clouds high up; he heard the loud roar of some distant animal. In another,

he saw the vague shape of two cats huddled together with heads bowed,

waiting in the pouring rain; they were so hungry and in such trouble that

when he saw them, a grief he could not understand welled up inside him

like a pain. In a third dream, he was standing on a windswept cliff high

above the sea. There were dark gorse bushes under a strange, unreal light.

There was a sense of vast space, the sound of water crashing rhythmically

on rocks below. In the teeth of the wind, Tag heard a voice at his side

say quietly, "I am one who becomes two; I am two who become four; I am

four who become eight; I am one more after that." It was the voice of a

cat. Or was it?

"Tintagel," it said. "Tag! Tag! Listen! Listen to the waves!"

All the dreams were different, but that voice was always the same--quiet,

persuasive, companionable, frightening. It wanted to tell him things. It

wanted him to do things.

All the dreams were strange; but perhaps this was the strangest dream of

all.

He dreamed it was evening, and he was sitting on a windowsill while behind

him in the room, the dulls ate their food, talking and waving their big

arms about. Tag stared out. It was dark. There were clouds high up,

obscuring the waning moon, but the moonlight broke fitfully through.

Something was happening at the very end of the garden. He couldn't quite

see what it was. Every night, he sensed, animals went along the path down

there, entering the garden at one side and leaving at the other. They were

on business of their own, business to enthral a young cat. It was a

highway, with constantly exciting traffic.

In the dream there was an animal out there, but he couldn't see it clearly

or hear it. For a moment the moonlight seemed to resolve it into the shape

of a large black cat--a cat with only one eye. Then it was nothing but a

shadow again. He shifted his feet uneasily. He wanted to be out there; he

didn't want to be out there. Clouds obscured the moon again. He put his

face close to the glass. "Be quiet!" he tried to tell the dulls. "Watch!

Watch now!"

As he spoke, the animal out there seemed to see him. He felt its eye on

him. He felt its will begin to engage his own. He thought he heard it

whisper, "I have a task for you, Tag. A great task!"

Behind him in the room, the dulls laughed at something one of them had

said. Tag shook himself, expecting to wake up. But when he looked around,

he was still in that room, and he had never been asleep. As if sensing his

confusion, the female got up and, putting her face close to his as if it

wanted to see exactly what he was seeing, stared out into the darkness. It

shivered. "You don't want to go out there," it said softly. "Cold and

dangerous for a little cat like you. Brrr!" It stroked his head. The purr

rose in Tag's throat. When he turned back to the garden, the one-eyed cat

had gone.

Early one morning, before the household was awake, Tag saw the sun coming

up, carmine colored, flat and pale with promise. A few shreds of mist hung

about the branches of the lime trees. Soon, three or four sparrows and a

robin had alighted on the lawn and begun hopping about among the fallen

leaves. This was all as it should be. Tag hunched forward to get a better

look. My birds! he thought. But then they flew up suddenly, to be replaced

by his enemy the magpie, who strode on long legs in a rough circle around

the birdbath, shining with health and self-importance. It stopped,

stretched its neck, opened its beak to reveal a short thick purple-gray

tongue, and let forth its abrasive cry.

"Raaark. Raaark."

Oh yes? thought Tag. We'll see about that!

But what could he do? Only jump on and off the windowsill in a fever of

frustration. At last he heard the dulls getting up, and there was

something else to think about. He raced down the stairs and stood by his

bowl in the kitchen.

"Breakfast," he demanded. Chicken and game casserole! "In here. Put it in

this bowl. Breakfast!"

Chicken and game!

That was a smell he would remember later on.

Two minutes after he had got his face into the bowl, one of the dulls

opened the back door without thinking. Tag felt the cool morning air on

his nose. It was full of smells. It was full of opportunity. And the

magpie was still out there, strutting around the lawn as if he owned it.

My lawn! thought Tag. Breakfast later!

And he was out in a flash, straight between a pair of legs, across the

lawn--scattering leaves and hurling himself at the bird, who turned its sly

black head at the last moment, said clearly, "Not this time, sonny," and

flew like an arrow through a hole in the fence, leaving one small white

body feather floating in the air behind it. Tag, enraged, went sprinting

after, his hind feet digging up lawn and flower bed. He heard the dulls

shouting after him. Then he was through the fence and into the garden next

door. The magpie was sitting on a fence, regarding him amusedly from one

beady eye. "Raaark." Off they went again. Every time he thought he had

caught it, the bird only led him farther afield, until, when Tag looked

back at his house, he couldn't see it any more.

He hesitated a moment.

"Call yourself a cat?" sneered the magpie, almost in his ear. "This is

where you belong, out here in the wild world--not a toy cat on a

windowsill!" But when Tag whirled around, ready to renew the chase, it had

vanished into thin air.

Tag sat down and washed himself. He looked around.

New gardens! New gardens that went on forever. Through one and into the

next, forever.

Out! he thought. I got out!

He forgot the magpie. He forgot his home. For the rest of that day he was

as happy as he'd ever been. He explored the new gardens one by one, moving

farther and farther away from the dulls and their house. There were

gardens overgrown with weeds and elder, in which the sun barely struck

through to the earth and the dusty, powerfully smelling roots. There were

gardens so neat they were just like front rooms. There were gardens full

of rusty household objects. Tag had a look at all of them. They were all

interesting. But by late afternoon he had found the garden of his dreams.

It was wilder than his own, a narrow shady cleft between old brick walls,

sagging wooden trellis, and overgrown buddleia bushes, into which reached

long bright fingers of sun. It was full of ancient flowerpots and white

metal garden furniture green with moss. At one side was a bent old damson

tree, its sagging boughs held up by wooden supports; at the other a

well-grown holly. Tag sat in the sun between them, cleaning his fur. A

family of bullfinches piped from the branches of the damson. A bee hummed

past! After it he went, whacking out with his front paws until he could

clutch the stunned insect inside one of them. He put the bee carefully

into his mouth and let it buzz about a bit in there. What a feeling! Then

he swallowed it. "Not bad," he told himself. "Good bee." For a while he

patrolled an old flower bed now overgrown with mint, in case he got

another. After that, he went to sleep. When he woke up, he was hungry. It

was late afternoon, and he had no idea where he was.

Two hours later, he was huddled--hungry, cold, and disoriented--on someone's

back doorstep. Afternoon had given way to evening as he made his way from

garden to garden, recognizing nothing. At first it had seemed like a great

game. Then the fences had got higher and harder to jump, the tangled rose

briars harder to push through, the smells of other cats more threatening.

Human beings had shouted at him through a window--he had run off

thoughtlessly and got turned back on himself, ending up in the garden he

had started from. Now he was so tired he couldn't think. He knew it wasn't

his own house. But he was grateful to sit on the doorstep anyway. He was

grateful for the old damson tree, spreading its branches over the white

garden furniture glowing in the dusk. These things were familiar, at

least. He gave a little yowl now and then, in case someone came home and

let him in.

As he sat there, the light went slowly out of the sky. The sun was a great

cool red ball behind the garden trees. Rooks began to settle their evening

quarrels--"My branch, I think." "No, my branch!"--the whole ragged ignoble

colony of them whirling up into the sky to wheel and caw before settling

again, one by one into silence. Suddenly the air was colder. Shadows crept

out of the box hedges. The garden seemed to change shape, becoming shorter

and broader. The lawn, the shrubs in their borders, the lighted windows of

the houses yellow with warmth and company--everything seemed closer and yet

further away. The apple trees faded to a uniform gray.

Night had come. Tag had never been out in it before.

He knew the night only from warm rooms behind double-glazed windows. Then

it had seemed exciting. Now it was only menacing and strange. As human

activity decreased, the real sounds and smells of the world came through:

the sudden low twitter of a bird disturbed, the slow tarry reek of leaf

mold from under the hedges, the bitter smell of a rusting iron bucket, a

dog barking somewhere down at the end of the road, thickly woven odors of

snails eating their way through the soft fleshy leaves of the hostas. And

then, suddenly, from the gloom at the very end of the garden, came a smell

that made Tag's heart race with fear and excitement! His head went up.

Almost despite himself, he sniffed the air. Something moving down there!

It was a highway, like the one that ran along the bottom of his own

garden! Something was trotting down there, fast and purposeful, its paws

moving silently across the broken, lichenous old flagstones as it made its

way from left to right along the tunnelly overgrown path between the

flower bed and the sagging board fence. Tag could barely keep still. He

wanted to make himself known. He wanted to hide. Every part of him wanted

to say something. Every part of him wanted to stay silent.

In the end, though, he must have moved, or made some sound, because the

animal on the highway stopped. It sniffed the air for him. He heard it.

Terribly afraid, he huddled into the doorway. Too late. It was aware of

him. He could see a dark silhouette, a thick black shadow with four legs

and a blunt muzzle, its head turning this way and that. A single bright,

pale, reflective eye that seemed to switch itself on suddenly, like a

lamp. It was looking at him. There was a long pause. Then a wave of scent,

a sharp, live, musky reek in the garden air.

"Little cat," it said in a soft voice. "Your true name is not Tag. Do you

want to discover your true name? If so, you must undertake the task which

lies before you."

He shrank back in the doorway until his head was pressed so tightly into

the corner his face hurt. To no avail. The thing that inhabited that

shadow could see him whatever he did. There was a low, grunting laugh.

"Don't be afraid," said the voice. "Come with me now."

Its owner took a pace toward him.

He cowered into his doorway.

There was a sudden impatient sigh, as if the creature had been

interrupted. It paused to listen, then, purposeful and urgent, it loped

off into the night without another word.

Tag huddled on the doorstep until it was light again. Exhaustion made him

shake; anxiety kept him awake. Every sound, familiar or not, seemed to

threaten him, from the abrupt shriek of an owl to the patient snuffling

and rootling of a hedgehog in the next garden. He was afraid to make any

noise of his own.

Toward dawn he fell into a restless sleep, only to dream of the animals on

their highway. Tag could never be sure what he saw--what he sensed--moving

along it. They were cats, certainly, although in the dream they seemed

much larger than a cat should be, and they had deeply disturbing, shadowy

shapes. They moved in their own powerful stink--vague, slippery,

indistinct, always angry or excited. Their voices came toward him from a

long distance, in the echoing yet glutinous speech of dreams.

"A task," they told him, "a great task."

The next morning he was stiff and tired, but the sunshine made him feel

optimistic. Breakfast! he thought. He sat up, stretched himself, and gave

a huge yawn. "Chicken and game!" He jumped on top of a fence and looked

across the gardens. They lay before him: a lawn as precise as a living

room carpet, bordered with regiments of red flowers; then rusty objects

propped against a shed; then bedsheets flapping on a line. He jumped down,

nosed around. There, on the concrete path as it warmed up in the sunshine,

was his own smell from yesterday, faint but distinct!

Follow myself home, he thought. No problem.

But it was a problem.

Chasing the magpie, he had taken an alarmingly random course, zigzagging,

turning back on himself, often going in circles. In the night, other

animals had passed; other scents had overlaid his own. While it was a good

idea, the attempt to follow himself was doomed from the start. High old

brick walls, espaliered with fruit trees, blocked his path. Abundant crops

of nettles forced him to divert. He blundered into another cat--or rather

the insane face of another cat was thrust unexpectedly into his own,

screaming at him so loudly that he jumped in fear and ran off under some

bushes and came out disoriented twenty minutes later to find himself

trapped in a place that didn't even seem to be a garden. The spines of

dying foxgloves mopped and mowed against a tottering wooden fence. What

had once been an open space was now a jungle: fireweed seeding down to

ashes, a choke of brambles and old rose suckers bound together in the

dusty heat by convolvulus and grape ivy. The air was thick, still, and

oppressive, full of the sleepy drone of insects. Eventually he pushed his

way out. He was hot and tired and out of temper. The house in front of him

had blue shutters, peeling to show the gray wood beneath, and a blue door.

Not much else could be seen through the skeins of honeysuckle and wiry

climbing roses colonizing its pebble-dashed walls. Its windows were of

rippled glass, dim with dirt. Compressed between the wilderness and the

house, the remains of its garden--the patch of yellowed lawn on which he

stood, the beds overgrown with rubbery hostas, the tottering wooden shed

which had also at some point been painted blue--would soon be engulfed.

Tag sighed and sat down suddenly in the shade of some terra-cotta pots

full of dead geraniums. It was already noon, and he still hadn't eaten. He

crouched down, tucked his front paws neatly under him, and let his nose

rest on the ground. Not knowing what else to do, he slept. When he woke,

the magpie was perched on a broken pot in front of him.

"Raaark," it said "On your own then, Kit-e-Kat?"

"Don't call me that!" said Tag.

The magpie laughed. "Call yourself a cat?" it asked. It added

mysteriously, "I don't know why he bothers with you. If he could find them

on his own, he wouldn't." Then it put its head on one side, regarded him

with one beady eye, and said with measured nastiness, "Oh yes, you're on

your own now, Kit-e-Kat!"

Tag was enraged. He jumped up and rushed the magpie. "My name's Tag!" he

cried. "I am a cat, and they call me Tag, not Kit-e-Kat!"

The magpie only bobbed its head wickedly and took flight. It flapped with

a dreamy slowness up from the lawn and into the rowan tree. As it flew it

looked less like a bird than a series of brilliant sketches of one. For an

instant--while it was still rising but almost into the tree--it seemed to

wear its own wings like a black, shiny cloak. Then it perched, quickly

ruffled its feathers, and looked down at Tag, its head tilted on one side

to show a bright cruel eye.

"They call me One for Sorrow," it said. "And you won't forget me in a

hurry."

Alone, thought Tag.

He tested this idea until sudden panic swept through him. He ran around

and around the lawn until he was tired again. He licked his fur in the

sunshine for ten minutes. He couldn't think what to do. He jumped up onto

a windowsill and rubbed both sides of his face on the window pane.

"Breakfast!" he demanded. But clearly it would not be feeding him today.

So he jumped down and tried the same with the back door. No luck. Clearly

no one would be feeding him today.

He had a new idea. He would feed himself.

Eat a bee, he thought. Eat more than one.

And he tore off excitedly across the lawn, the little bell on his collar

jingling.

An hour later he had chased four houseflies, a blackbird, two sparrows,

and a leaf. He had caught one of the houseflies and the leaf. The leaf

proved to be unpalatable. No bees were about. All this effort made him

hungrier than before. He went back to the house and jumped up on the

windowsill again.

"Yow!" he said.

Nothing. It was silent and empty in there.

He stalked a wren, which scolded him from a safe place inside a hedge. He

tried it on with two squirrels, who bobbed their tails at him and sped off

along the top of a board fence at a breakneck pace, vying with each other

for the lead and calling "Stuff you!" and "Stuff your nuts, mate!" as they

ran. Then he tried a thrush, which kept a lazy eye on him while it shelled

its breakfast--a yellow snail--against a stone, then rose up neatly as he

pounced, and with no fuss or fluster cleared his optimistic jaws by four

inches and left him clapping his front paws silently on empty air.

"Nice technique," said an interested voice behind him.

"Pretty stupid cat, though," answered another. "Anyone could have caught

that."

Tag thought he recognized one of the voices, but he was too ashamed to

turn around and look. For the rest of that day, he ate flies. They were

easy to catch and, depending on what they had eaten recently, even tasted

good. In the middle of the afternoon he bullied some sparrows off half a

slice of buttered white bread two gardens along the row. Finally, he went

back to the place where he had argued with the thrush. There he caught

some snails. They didn't taste in the slightest bit good, but at least, he

thought, he was denying them to the thrush.

Toward evening it began to rain.

The rain came stealthily at first, a drop here and a drop there. It tapped

and popped on the leaves of the hostas, where it gathered as shiny

beads--each containing a tiny curved image of the world--that soon collapsed

into little short-lived rivulets. The snails, sensing the rain, opened

themselves up gratefully. Then, sensing Tag, they shut themselves away

again. There was a kind of hush around the sound of each raindrop.

Tag watched the snails and waited. A cat with a thick coat doesn't feel

the rain until too late. Suddenly it was pouring down on him, straight as

a stair rod, cold and penetrating as a needle. He was surprised and

disgusted to find himself soaked. His skin twitched. He stretched and

stood up. He shook out first one front paw, then the other. He retreated

to the back doorstep.

No good.

A gust of wind shook the shrubbery and blew the rain across the garden in

swirls, right into his shelter. He sat there grimly for a bit, trying to

lick the damp off his fur, fluffing up, blinking, shaking himself, licking

again. But in the end he had to admit that he was just as wet there as he

would have been in the middle of the lawn.

I hate rain, he thought.

He dashed out into the downpour to try the windowsill.

Wet.

He found a dry patch in the lee of the terra-cotta pots. The wind changed

and blew the rain into his face.

He tried sitting under the trees.

Wet.

Soon it was coming dark. "Stop raining now," said Tag. Every time he

changed position he got wetter. He was hungry again, and cold. But if he

scampered about to keep warm he felt tired very suddenly. He ordered the

rain, "Leave me alone, now." The rain didn't listen. The garden didn't

listen. The wind was like a live thing. It was always blowing from behind

him, ruffling his fur up the wrong way to find and chill any part of him

that still had any warmth left. He turned around and tried to bite the

harder gusts. He ran blindly about or simply sat, becoming more and more

bedraggled. Suddenly he realized that he was sitting by the door of the

garden shed.

Inside, he thought.

He hooked his paw around the bottom of the door and pulled hard. It

wouldn't move. Open! he heard himself think. Open, now! He hooked again

and pulled harder. This made him so weary he needed to sit down; but after

a moment he was cold again and had to force himself to get up.

Hook. Pull. No good.

"Come on, Tag," he encouraged himself. "Come on!"

Hook. Pull. The door scraped open an inch. Then two.

That's enough! thought Tag.

For some minutes he was too worn out to do anything but sit in front of

the door with his head down, looking at nothing. Then he pushed his face

cautiously into the gap, and the rest of him, bedraggled and shivering,

seemed to follow of its own accord.

It rained. Days and nights came and went, and still no one summoned him

for "the task." The house remained empty and the lawn filled with puddles.

Then the last leaves fell from the trees, and the nights drew in tight,

like a collar around a young cat's neck. Smoke hung low over the gardens

in the late afternoon; the days began with thick mists. Winter ushered

itself in, quietly and without fuss, in the voice of the roosting crows,

the raw chill in the evening air. Tag lived in the shed, and soon became

familiar with its pungent smells

of ancient sacks and insecticides, spiderwebs and mice. He never caught a

mouse there, but it was reassuring to think that one day he might. If it

was not warm, the shed was at least dry. The shed saved him.

When he felt strong, he ranged up and down the gardens, three or four

houses in every direction. He ate flies. He ate earthworms. He ate

anything that could be caught without a great expenditure of energy. He

got up in the dawn to beat the squirrels to the scraps of bread and lard

and meat that other cats' dulls put out for the birds. He became thin and

quick but easier and easier to tire. He avoided confrontations. Seen in

the distance in the gardens at sunrise on a cold morning, he was like a

white ghost, a twist of breath in the frost. Close to, his silver coat was

tangled and muddy and out of condition.

Some days it was all he could do to find the energy to crouch at a puddle

and lap up rainwater, then make his way back to the shed. Eat something

tomorrow, he would think; and then after a confused doze get up again in

the belief that tomorrow had already come. Which in a way it had.

He never left the gardens. If he thought about his life, he thought that

this was the way he would live it now. Tiredness, and the comforting sound

of the rain on the roof of the shed.

Then one night everything changed again.

prowling shadow in a jungle.

--Karel Capek

They called the kitten Tag. They fed him, and he grew. They put a collar

around his neck. They entertained him, and the world began to take on

shape.

It was his world, full of novelty yet always reliable, exciting yet

secure. He was a small king; and by the time a week was out, he had

explored every inch of his new kingdom. He liked the kitchen best. It was

warm in there on a cold day, and from the windowsill he could see out into

the garden. In the kitchen they made food, which was easy to get off them.

He had bowls of his own to eat it from. He had a box of clean dirt to

scrat in. The kitchen wasn't entirely comfortable--especially in the

morning, when things went off or went around very loudly without

warning--but elsewhere they had given him a large sofa, covered in dark red

velvet, among the scattered cushions of which he scrabbled and burrowed

and slept. He had brass tubs with plants and some very interesting

fireplaces full of dried flowers, out of which flowed odors damp and sooty.

Up a flight of stairs and into every room, every cupboard and corner! It

was big up there, and full of unattended human things. At first he

wouldn't go on his own but always made one of them accompany him while he

inspected the shelves stuffed with clean linen and dusty books.

"Come on, come on!" he urged them. "Here now! Look, here!" They never

answered.

They were too dull.

A further flight up, and it was as if nobody had ever lived there--echoes

on the uncarpeted stairs, gray floorboards and open doors, pale bright

light pouring in through uncurtained windows. Up there, each bare floor

had a smell of its own; each ball of fluff had a personality. If he

listened, he could hear dead spiders contracting behind the woodwork. Left

to himself up there he danced, for reasons he barely understood. It was a

territorial dance, grave yet full of energy. Simply to occupy the space,

perhaps, he leapt and pounced and hurled himself about, then slept in a

pool of sunshine as if someone had switched him off. When he woke, the sun

had moved away, and they were calling him to come and eat more new things.

They called him Tag. He called them dull.

"Come on, dulls!" he urged them. "Come on!"

They had a room where they poured water on themselves. Every morning he

hid outside it and jumped out on the big dull bare feet that passed. Nice

but dull, they were never quick enough or nimble enough to avoid him. They

never learned. They remained shadowy to him--a large smell, cheerful if

meaningless goings-on, a caring face suspended over him like the moon

through the window if he woke afraid. They remained patient, amiable,

easily convinced, less focused than a tin of meat-and-liver dinner. The

dulls were for food or comfort or play. Especially for play. One of his

earliest memories was of chasing soap bubbles. The light of an autumn

evening shifted gently from blue to a deep orange. Up and down the room

rushed Tag, clapping his front paws in the air. He loved the movement. He

loved the heavy warmth of the air. Everything was exciting. Everything was

golden. The iridescence of each bubble was a brand-new world, a brand-new

opportunity. It was like waking up in the morning.

Bubble! Tag thought. Another bubble!

He thought, Chase the bubbles!

As leggy and unsteady, as easily surprised, as easy to tease, as full of

daft energy as every kitten, Tag pursued the bubbles, and the bubbles--each

with its tiny reflected picture of the room in strange, slippery

colors--evaded him smoothly and neatly and then hid among a sheaf of dried

flowers or floated slowly up the chimney or blundered without a care into

a piece of furniture and burst. He heard them burst, in a way a human

being never could, with a sound like tapped porcelain.

Evanescence and infinite renewal!

Any cat who wants to live forever should watch bubbles. Only kittens

should chase them.

Tag would chase anything. But the toy he enjoyed most was a small cloth

mouse with a very energetic odor. It had been bright red to start with.

Now it was rather dirty, and to its original smell had been added that of

floor polish. Tag whacked it around the shiny living room floor. Off it

skidded. Tag skidded after it, scrabbling to keep upright on the tighter

turns.

One day he found a real mouse hiding under the Welsh dresser.

A real mouse was a different thing.

Tag could see it, a little pointed black shape against the gray dimness.

He could smell it too, sharp and terrified against the customary smell of

fluff balls and seasoned pine. It knew he was there! It kept very still,

but there was a lick of light off one beady eye, and he could feel the

thoughts racing and racing through its tiny head. All the mouse's fear was

trapped there under the dresser, stretched taut between the two of them

like a wire. Tag vibrated with it. He wanted to chase and pounce. He

wanted to eat the mouse: he didn't want to eat it. He felt powerful and

predatory; he felt bigger than himself. At the same time he was anxious

and frightened--for himself and the mouse. Eating someone was such a big

step. He rather regretted his bravado with the pet shop finches.

He watched the mouse for some time. It watched him. Suddenly, Tag decided

not to change either of their lives. His old cloth mouse had a nicer smell

anyway. He reached in expertly, hooked it out, and walked away with it in

his jaws. "Got you!" he told it. He flung it in the air and caught it.

After a few minutes he had forgotten the real mouse, though it probably

never forgot him--and his dreams were never the same.

That afternoon he took the cloth mouse with him up to the third floor

where he could pat it about in a drench of cool light.

When he got bored with this he jumped up on the windowsill. From up there

he had a view of the gardens stretching away right and left between the

houses. However much he cajoled or bullied them, the dulls never seemed to

understand that he wanted to go out there. It fascinated him. His own

garden had a lawn full of moss and clover that sloped down toward the

house, where a steep rockery gave way to the lichen-stained tiles of the

checkerboard patio. Lime trees overhung the back fence, along which--almost

obscured by colonies of cotoneaster, monbretia, and fuchsia--ran a dark,

narrow path of crazy paving. Cool smells came up from the garden after

rain. Wood pigeons shifted furtively in the branches all endless sunny

afternoon, then burst into loud, aimless cooing. At twilight, the sleepy

liquid call of blackbird and thrush seemed to come from another world; and

the greens of the lawn looked mysterious and unreal. Dawn filled the trees

with squirrels, who chased one another from branch to branch, looting as

they went, while birds quartered the lawn or hopped in circles around the

mossy stone birdbath.

Transfixed with excitement, Tag watched them pull up worms.

That afternoon, a magpie was in blatant possession of the lawn, strutting

around the birdbath and every so often emitting loud and raucous cries. It

was a big, glossy bird, proud of its elegant black-and-white livery and

metallic blue flashes. Tag had seen it before. He hated its bobbing head

and powerful, ugly beak. He hated its flat, ironic eyes. Most of all he

hated the way it seemed to look directly up at him, as if to say, My lawn!

Tag narrowed his eyes. Angry chattering sounds he couldn't control came

from his throat. He jumped off the windowsill, then back up again.

"Wrong!" he said. "Wrong!"

But the bird pretended not to hear him--though he was certain it could--and

unable to bear its smug proprietorial air, Tag sat down, curled his tail

around himself, and closed his eyes. After a while, he fell asleep,

thinking confusedly, My mouse. This seemed to lead him into a dream.

He dreamed that he was under the Welsh dresser, eating something. Somehow,

the dark gap beneath the dresser was big enough for him to enter; he had

followed something in there, and was eating it. The soft parts had a warm,

acrid, salty taste, and he could hardly get them down fast enough. Before

he was able to swallow the tougher bits he had to shear them with the

carnassial teeth at the side of his jaw, breathing heavily through his

mouth as he did so. That was enjoyable too. Just as he was finishing

off--licking his lips, snuffing the dusty floor where it had been in case

he had missed anything--he heard a voice in the dark whisper quite close to

him, "Tag is not your true name."

He whirled around. Nothing. Yet someone was there under the dresser with

him. He could almost feel the heat of its body, the smell of its breath,

the unsettling companionable feel of it. It had quietly watched him eat

and said nothing. Now he felt guilty, angry, afraid. His fur bristled. He

tried to back out from under the dresser, but now everything was the right

size again and he was stuck, squeezed down tight in a dark space that

smelled of wood and dust and blood with a creature he couldn't see. "Tag,"

it whispered. "Listen. Tag is not your true name." He felt that if he

stayed there any longer, it would push its face right into his, touch him

in the dark, tell him something he didn't want to hear ...

"Tag is my name!" he cried, and woke up--to a loud, rapid hammering noise

near his ear. While he slept, the magpie had flown up from the garden. It

was strutting to and fro on the ledge directly outside the window,

screeching and cawing, flapping its wings against the glass, filling the

whole world with its clamor. Now its face was right next to his, and its

chipped, wicked beak was drumming against the glass and it was shouting at

him.

"Call yourself a cat? Call yourself a cat?"

And he fell off the windowsill and hit his head hard on the floor.

Everything went a soft dark brown color, like comforting fur. When he woke

up again, the bird was gone and he could hear the dulls preparing their

food downstairs, and he thought it had all been the same dream.

Tag had lived in the house for two months. It seemed much longer, a great

stretch of time in which he was never unhappy. He never wanted for

anything. He doubled in size. His sleep was sound, his dreams infrequent

and full of kitten things. All that seemed to be changing. Now, as he

curled up on the velvet sofa, he wondered what would happen when he closed

his eyes. Each time he slept, he lived another life--or fragments of it, a

life of which he had no understanding.

In one dream he was walking beneath a sliver of yellow moon, with ragged

clouds high up; he heard the loud roar of some distant animal. In another,

he saw the vague shape of two cats huddled together with heads bowed,

waiting in the pouring rain; they were so hungry and in such trouble that

when he saw them, a grief he could not understand welled up inside him

like a pain. In a third dream, he was standing on a windswept cliff high

above the sea. There were dark gorse bushes under a strange, unreal light.

There was a sense of vast space, the sound of water crashing rhythmically

on rocks below. In the teeth of the wind, Tag heard a voice at his side

say quietly, "I am one who becomes two; I am two who become four; I am

four who become eight; I am one more after that." It was the voice of a

cat. Or was it?

"Tintagel," it said. "Tag! Tag! Listen! Listen to the waves!"

All the dreams were different, but that voice was always the same--quiet,

persuasive, companionable, frightening. It wanted to tell him things. It

wanted him to do things.

All the dreams were strange; but perhaps this was the strangest dream of

all.

He dreamed it was evening, and he was sitting on a windowsill while behind

him in the room, the dulls ate their food, talking and waving their big

arms about. Tag stared out. It was dark. There were clouds high up,

obscuring the waning moon, but the moonlight broke fitfully through.

Something was happening at the very end of the garden. He couldn't quite

see what it was. Every night, he sensed, animals went along the path down

there, entering the garden at one side and leaving at the other. They were

on business of their own, business to enthral a young cat. It was a

highway, with constantly exciting traffic.

In the dream there was an animal out there, but he couldn't see it clearly

or hear it. For a moment the moonlight seemed to resolve it into the shape

of a large black cat--a cat with only one eye. Then it was nothing but a

shadow again. He shifted his feet uneasily. He wanted to be out there; he

didn't want to be out there. Clouds obscured the moon again. He put his

face close to the glass. "Be quiet!" he tried to tell the dulls. "Watch!

Watch now!"

As he spoke, the animal out there seemed to see him. He felt its eye on

him. He felt its will begin to engage his own. He thought he heard it

whisper, "I have a task for you, Tag. A great task!"

Behind him in the room, the dulls laughed at something one of them had

said. Tag shook himself, expecting to wake up. But when he looked around,

he was still in that room, and he had never been asleep. As if sensing his

confusion, the female got up and, putting her face close to his as if it

wanted to see exactly what he was seeing, stared out into the darkness. It

shivered. "You don't want to go out there," it said softly. "Cold and

dangerous for a little cat like you. Brrr!" It stroked his head. The purr

rose in Tag's throat. When he turned back to the garden, the one-eyed cat

had gone.

Early one morning, before the household was awake, Tag saw the sun coming

up, carmine colored, flat and pale with promise. A few shreds of mist hung

about the branches of the lime trees. Soon, three or four sparrows and a

robin had alighted on the lawn and begun hopping about among the fallen

leaves. This was all as it should be. Tag hunched forward to get a better

look. My birds! he thought. But then they flew up suddenly, to be replaced

by his enemy the magpie, who strode on long legs in a rough circle around

the birdbath, shining with health and self-importance. It stopped,

stretched its neck, opened its beak to reveal a short thick purple-gray

tongue, and let forth its abrasive cry.

"Raaark. Raaark."

Oh yes? thought Tag. We'll see about that!

But what could he do? Only jump on and off the windowsill in a fever of

frustration. At last he heard the dulls getting up, and there was

something else to think about. He raced down the stairs and stood by his

bowl in the kitchen.

"Breakfast," he demanded. Chicken and game casserole! "In here. Put it in

this bowl. Breakfast!"

Chicken and game!

That was a smell he would remember later on.

Two minutes after he had got his face into the bowl, one of the dulls

opened the back door without thinking. Tag felt the cool morning air on

his nose. It was full of smells. It was full of opportunity. And the

magpie was still out there, strutting around the lawn as if he owned it.

My lawn! thought Tag. Breakfast later!

And he was out in a flash, straight between a pair of legs, across the

lawn--scattering leaves and hurling himself at the bird, who turned its sly

black head at the last moment, said clearly, "Not this time, sonny," and

flew like an arrow through a hole in the fence, leaving one small white

body feather floating in the air behind it. Tag, enraged, went sprinting

after, his hind feet digging up lawn and flower bed. He heard the dulls

shouting after him. Then he was through the fence and into the garden next

door. The magpie was sitting on a fence, regarding him amusedly from one

beady eye. "Raaark." Off they went again. Every time he thought he had

caught it, the bird only led him farther afield, until, when Tag looked

back at his house, he couldn't see it any more.

He hesitated a moment.

"Call yourself a cat?" sneered the magpie, almost in his ear. "This is

where you belong, out here in the wild world--not a toy cat on a

windowsill!" But when Tag whirled around, ready to renew the chase, it had

vanished into thin air.

Tag sat down and washed himself. He looked around.

New gardens! New gardens that went on forever. Through one and into the

next, forever.

Out! he thought. I got out!

He forgot the magpie. He forgot his home. For the rest of that day he was

as happy as he'd ever been. He explored the new gardens one by one, moving

farther and farther away from the dulls and their house. There were

gardens overgrown with weeds and elder, in which the sun barely struck

through to the earth and the dusty, powerfully smelling roots. There were

gardens so neat they were just like front rooms. There were gardens full

of rusty household objects. Tag had a look at all of them. They were all

interesting. But by late afternoon he had found the garden of his dreams.

It was wilder than his own, a narrow shady cleft between old brick walls,

sagging wooden trellis, and overgrown buddleia bushes, into which reached

long bright fingers of sun. It was full of ancient flowerpots and white

metal garden furniture green with moss. At one side was a bent old damson

tree, its sagging boughs held up by wooden supports; at the other a

well-grown holly. Tag sat in the sun between them, cleaning his fur. A

family of bullfinches piped from the branches of the damson. A bee hummed

past! After it he went, whacking out with his front paws until he could

clutch the stunned insect inside one of them. He put the bee carefully

into his mouth and let it buzz about a bit in there. What a feeling! Then

he swallowed it. "Not bad," he told himself. "Good bee." For a while he

patrolled an old flower bed now overgrown with mint, in case he got

another. After that, he went to sleep. When he woke up, he was hungry. It

was late afternoon, and he had no idea where he was.

Two hours later, he was huddled--hungry, cold, and disoriented--on someone's

back doorstep. Afternoon had given way to evening as he made his way from

garden to garden, recognizing nothing. At first it had seemed like a great

game. Then the fences had got higher and harder to jump, the tangled rose

briars harder to push through, the smells of other cats more threatening.

Human beings had shouted at him through a window--he had run off

thoughtlessly and got turned back on himself, ending up in the garden he

had started from. Now he was so tired he couldn't think. He knew it wasn't

his own house. But he was grateful to sit on the doorstep anyway. He was

grateful for the old damson tree, spreading its branches over the white

garden furniture glowing in the dusk. These things were familiar, at

least. He gave a little yowl now and then, in case someone came home and

let him in.

As he sat there, the light went slowly out of the sky. The sun was a great

cool red ball behind the garden trees. Rooks began to settle their evening

quarrels--"My branch, I think." "No, my branch!"--the whole ragged ignoble

colony of them whirling up into the sky to wheel and caw before settling

again, one by one into silence. Suddenly the air was colder. Shadows crept

out of the box hedges. The garden seemed to change shape, becoming shorter

and broader. The lawn, the shrubs in their borders, the lighted windows of

the houses yellow with warmth and company--everything seemed closer and yet

further away. The apple trees faded to a uniform gray.

Night had come. Tag had never been out in it before.

He knew the night only from warm rooms behind double-glazed windows. Then

it had seemed exciting. Now it was only menacing and strange. As human

activity decreased, the real sounds and smells of the world came through:

the sudden low twitter of a bird disturbed, the slow tarry reek of leaf

mold from under the hedges, the bitter smell of a rusting iron bucket, a

dog barking somewhere down at the end of the road, thickly woven odors of

snails eating their way through the soft fleshy leaves of the hostas. And

then, suddenly, from the gloom at the very end of the garden, came a smell

that made Tag's heart race with fear and excitement! His head went up.

Almost despite himself, he sniffed the air. Something moving down there!

It was a highway, like the one that ran along the bottom of his own

garden! Something was trotting down there, fast and purposeful, its paws

moving silently across the broken, lichenous old flagstones as it made its

way from left to right along the tunnelly overgrown path between the

flower bed and the sagging board fence. Tag could barely keep still. He

wanted to make himself known. He wanted to hide. Every part of him wanted

to say something. Every part of him wanted to stay silent.

In the end, though, he must have moved, or made some sound, because the

animal on the highway stopped. It sniffed the air for him. He heard it.

Terribly afraid, he huddled into the doorway. Too late. It was aware of

him. He could see a dark silhouette, a thick black shadow with four legs

and a blunt muzzle, its head turning this way and that. A single bright,

pale, reflective eye that seemed to switch itself on suddenly, like a

lamp. It was looking at him. There was a long pause. Then a wave of scent,

a sharp, live, musky reek in the garden air.

"Little cat," it said in a soft voice. "Your true name is not Tag. Do you

want to discover your true name? If so, you must undertake the task which

lies before you."

He shrank back in the doorway until his head was pressed so tightly into

the corner his face hurt. To no avail. The thing that inhabited that

shadow could see him whatever he did. There was a low, grunting laugh.

"Don't be afraid," said the voice. "Come with me now."

Its owner took a pace toward him.

He cowered into his doorway.

There was a sudden impatient sigh, as if the creature had been

interrupted. It paused to listen, then, purposeful and urgent, it loped

off into the night without another word.

Tag huddled on the doorstep until it was light again. Exhaustion made him

shake; anxiety kept him awake. Every sound, familiar or not, seemed to

threaten him, from the abrupt shriek of an owl to the patient snuffling

and rootling of a hedgehog in the next garden. He was afraid to make any

noise of his own.

Toward dawn he fell into a restless sleep, only to dream of the animals on

their highway. Tag could never be sure what he saw--what he sensed--moving

along it. They were cats, certainly, although in the dream they seemed

much larger than a cat should be, and they had deeply disturbing, shadowy

shapes. They moved in their own powerful stink--vague, slippery,

indistinct, always angry or excited. Their voices came toward him from a

long distance, in the echoing yet glutinous speech of dreams.

"A task," they told him, "a great task."

The next morning he was stiff and tired, but the sunshine made him feel

optimistic. Breakfast! he thought. He sat up, stretched himself, and gave

a huge yawn. "Chicken and game!" He jumped on top of a fence and looked

across the gardens. They lay before him: a lawn as precise as a living

room carpet, bordered with regiments of red flowers; then rusty objects

propped against a shed; then bedsheets flapping on a line. He jumped down,

nosed around. There, on the concrete path as it warmed up in the sunshine,

was his own smell from yesterday, faint but distinct!

Follow myself home, he thought. No problem.

But it was a problem.

Chasing the magpie, he had taken an alarmingly random course, zigzagging,

turning back on himself, often going in circles. In the night, other

animals had passed; other scents had overlaid his own. While it was a good

idea, the attempt to follow himself was doomed from the start. High old

brick walls, espaliered with fruit trees, blocked his path. Abundant crops

of nettles forced him to divert. He blundered into another cat--or rather

the insane face of another cat was thrust unexpectedly into his own,

screaming at him so loudly that he jumped in fear and ran off under some

bushes and came out disoriented twenty minutes later to find himself

trapped in a place that didn't even seem to be a garden. The spines of

dying foxgloves mopped and mowed against a tottering wooden fence. What

had once been an open space was now a jungle: fireweed seeding down to

ashes, a choke of brambles and old rose suckers bound together in the

dusty heat by convolvulus and grape ivy. The air was thick, still, and

oppressive, full of the sleepy drone of insects. Eventually he pushed his

way out. He was hot and tired and out of temper. The house in front of him

had blue shutters, peeling to show the gray wood beneath, and a blue door.

Not much else could be seen through the skeins of honeysuckle and wiry

climbing roses colonizing its pebble-dashed walls. Its windows were of

rippled glass, dim with dirt. Compressed between the wilderness and the

house, the remains of its garden--the patch of yellowed lawn on which he

stood, the beds overgrown with rubbery hostas, the tottering wooden shed

which had also at some point been painted blue--would soon be engulfed.

Tag sighed and sat down suddenly in the shade of some terra-cotta pots

full of dead geraniums. It was already noon, and he still hadn't eaten. He

crouched down, tucked his front paws neatly under him, and let his nose

rest on the ground. Not knowing what else to do, he slept. When he woke,

the magpie was perched on a broken pot in front of him.

"Raaark," it said "On your own then, Kit-e-Kat?"

"Don't call me that!" said Tag.

The magpie laughed. "Call yourself a cat?" it asked. It added

mysteriously, "I don't know why he bothers with you. If he could find them

on his own, he wouldn't." Then it put its head on one side, regarded him

with one beady eye, and said with measured nastiness, "Oh yes, you're on

your own now, Kit-e-Kat!"

Tag was enraged. He jumped up and rushed the magpie. "My name's Tag!" he

cried. "I am a cat, and they call me Tag, not Kit-e-Kat!"

The magpie only bobbed its head wickedly and took flight. It flapped with

a dreamy slowness up from the lawn and into the rowan tree. As it flew it

looked less like a bird than a series of brilliant sketches of one. For an

instant--while it was still rising but almost into the tree--it seemed to

wear its own wings like a black, shiny cloak. Then it perched, quickly

ruffled its feathers, and looked down at Tag, its head tilted on one side

to show a bright cruel eye.

"They call me One for Sorrow," it said. "And you won't forget me in a

hurry."

Alone, thought Tag.

He tested this idea until sudden panic swept through him. He ran around

and around the lawn until he was tired again. He licked his fur in the

sunshine for ten minutes. He couldn't think what to do. He jumped up onto

a windowsill and rubbed both sides of his face on the window pane.

"Breakfast!" he demanded. But clearly it would not be feeding him today.

So he jumped down and tried the same with the back door. No luck. Clearly

no one would be feeding him today.

He had a new idea. He would feed himself.

Eat a bee, he thought. Eat more than one.

And he tore off excitedly across the lawn, the little bell on his collar

jingling.

An hour later he had chased four houseflies, a blackbird, two sparrows,

and a leaf. He had caught one of the houseflies and the leaf. The leaf

proved to be unpalatable. No bees were about. All this effort made him

hungrier than before. He went back to the house and jumped up on the

windowsill again.

"Yow!" he said.

Nothing. It was silent and empty in there.

He stalked a wren, which scolded him from a safe place inside a hedge. He

tried it on with two squirrels, who bobbed their tails at him and sped off

along the top of a board fence at a breakneck pace, vying with each other

for the lead and calling "Stuff you!" and "Stuff your nuts, mate!" as they

ran. Then he tried a thrush, which kept a lazy eye on him while it shelled

its breakfast--a yellow snail--against a stone, then rose up neatly as he

pounced, and with no fuss or fluster cleared his optimistic jaws by four

inches and left him clapping his front paws silently on empty air.

"Nice technique," said an interested voice behind him.

"Pretty stupid cat, though," answered another. "Anyone could have caught

that."

Tag thought he recognized one of the voices, but he was too ashamed to

turn around and look. For the rest of that day, he ate flies. They were

easy to catch and, depending on what they had eaten recently, even tasted

good. In the middle of the afternoon he bullied some sparrows off half a

slice of buttered white bread two gardens along the row. Finally, he went

back to the place where he had argued with the thrush. There he caught

some snails. They didn't taste in the slightest bit good, but at least, he

thought, he was denying them to the thrush.

Toward evening it began to rain.

The rain came stealthily at first, a drop here and a drop there. It tapped

and popped on the leaves of the hostas, where it gathered as shiny

beads--each containing a tiny curved image of the world--that soon collapsed

into little short-lived rivulets. The snails, sensing the rain, opened

themselves up gratefully. Then, sensing Tag, they shut themselves away

again. There was a kind of hush around the sound of each raindrop.

Tag watched the snails and waited. A cat with a thick coat doesn't feel

the rain until too late. Suddenly it was pouring down on him, straight as

a stair rod, cold and penetrating as a needle. He was surprised and

disgusted to find himself soaked. His skin twitched. He stretched and

stood up. He shook out first one front paw, then the other. He retreated

to the back doorstep.

No good.

A gust of wind shook the shrubbery and blew the rain across the garden in

swirls, right into his shelter. He sat there grimly for a bit, trying to

lick the damp off his fur, fluffing up, blinking, shaking himself, licking

again. But in the end he had to admit that he was just as wet there as he

would have been in the middle of the lawn.

I hate rain, he thought.

He dashed out into the downpour to try the windowsill.

Wet.

He found a dry patch in the lee of the terra-cotta pots. The wind changed

and blew the rain into his face.

He tried sitting under the trees.

Wet.

Soon it was coming dark. "Stop raining now," said Tag. Every time he

changed position he got wetter. He was hungry again, and cold. But if he

scampered about to keep warm he felt tired very suddenly. He ordered the

rain, "Leave me alone, now." The rain didn't listen. The garden didn't

listen. The wind was like a live thing. It was always blowing from behind

him, ruffling his fur up the wrong way to find and chill any part of him

that still had any warmth left. He turned around and tried to bite the

harder gusts. He ran blindly about or simply sat, becoming more and more

bedraggled. Suddenly he realized that he was sitting by the door of the

garden shed.

Inside, he thought.

He hooked his paw around the bottom of the door and pulled hard. It

wouldn't move. Open! he heard himself think. Open, now! He hooked again

and pulled harder. This made him so weary he needed to sit down; but after

a moment he was cold again and had to force himself to get up.

Hook. Pull. No good.

"Come on, Tag," he encouraged himself. "Come on!"

Hook. Pull. The door scraped open an inch. Then two.

That's enough! thought Tag.

For some minutes he was too worn out to do anything but sit in front of

the door with his head down, looking at nothing. Then he pushed his face

cautiously into the gap, and the rest of him, bedraggled and shivering,

seemed to follow of its own accord.

It rained. Days and nights came and went, and still no one summoned him

for "the task." The house remained empty and the lawn filled with puddles.

Then the last leaves fell from the trees, and the nights drew in tight,

like a collar around a young cat's neck. Smoke hung low over the gardens

in the late afternoon; the days began with thick mists. Winter ushered

itself in, quietly and without fuss, in the voice of the roosting crows,

the raw chill in the evening air. Tag lived in the shed, and soon became

familiar with its pungent smells

of ancient sacks and insecticides, spiderwebs and mice. He never caught a

mouse there, but it was reassuring to think that one day he might. If it

was not warm, the shed was at least dry. The shed saved him.

When he felt strong, he ranged up and down the gardens, three or four

houses in every direction. He ate flies. He ate earthworms. He ate

anything that could be caught without a great expenditure of energy. He

got up in the dawn to beat the squirrels to the scraps of bread and lard

and meat that other cats' dulls put out for the birds. He became thin and

quick but easier and easier to tire. He avoided confrontations. Seen in

the distance in the gardens at sunrise on a cold morning, he was like a

white ghost, a twist of breath in the frost. Close to, his silver coat was

tangled and muddy and out of condition.

Some days it was all he could do to find the energy to crouch at a puddle

and lap up rainwater, then make his way back to the shed. Eat something

tomorrow, he would think; and then after a confused doze get up again in

the belief that tomorrow had already come. Which in a way it had.

He never left the gardens. If he thought about his life, he thought that

this was the way he would live it now. Tiredness, and the comforting sound

of the rain on the roof of the shed.

Then one night everything changed again.

Recenzii

"Absolutely magical . . . Always intriguing."

--Richard Adams

Author of Watership Down

"A magical quest fantasy--a Watership Down for cat lovers."

--The Daily Telegraph (London)

"A diverting fantasy tale."

--USA Today

--Richard Adams

Author of Watership Down

"A magical quest fantasy--a Watership Down for cat lovers."

--The Daily Telegraph (London)

"A diverting fantasy tale."

--USA Today

Descriere

In the grand storytelling tradition of "Watership Down" and "Tailchaser's Song" comes an epic tale of adventure and danger, of heroism against insurmountable odds, and of love and comradeship among extraordinary animals who must brave "The Wild Road".