The Wild Things

Autor Dave Eggers Autor original Maurice Sendak Spike Jonzeen Limba Engleză Paperback – 28 feb 2010

In this visionary adaptation of Maurice Sendak's classic work, Dave Eggers brings an imaginary world vividly to life, telling the story of a lonely boy navigating the emotional journey away from boyhood.

Preț: 90.70 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 136

Preț estimativ în valută:

17.36€ • 18.02$ • 14.47£

17.36€ • 18.02$ • 14.47£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307475466

ISBN-10: 0307475468

Pagini: 284

Dimensiuni: 132 x 204 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.33 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 0307475468

Pagini: 284

Dimensiuni: 132 x 204 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.33 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

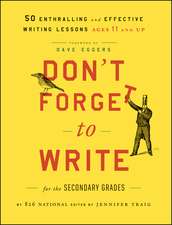

Notă biografică

Dave Eggers is the author of Zeitoun and What Is the What, among other books. He is the editor of McSweeney’s, an independent publishing house in San Francisco, and is the cofounder of 826 National, a network of nonprofit writing and tutoring centers for youth with locations in San Francisco, Los Angeles, New York, Chicago, Boston, Ann Arbor, and Seattle. With his weekly high school class he edits The Best American Nonrequired Reading, a yearly anthology, and with his brother Toph he cowrites the Haggis-on-Way series of semi-informative books, which includes Giraffes? Giraffes!, Animals of the Ocean (in Particular the Giant Squid), and Cold Fusion.

Extras

Matching Stumpy pant for pant, Max chased his cloudwhite

dog through the upstairs hallway, down the wooden stairs, and into the cold open foyer. Max and Stumpy did this often, running and wrestling through the house, though Max’s mother and sister, the two other occupants of the home, didn’t appreciate the volume and violence of the game. Max’s dad lived in the city and phoned on

Wednesdays and Sundays but sometimes did not.

Max lunged toward Stumpy, missed, barreled into the front door, and knocked the doorknob-basket off. The doorknob-basket was a small wicker vessel that Max thought was stupid but Max’s mom insisted on having on the front doorknob for good luck. The main thing the

basket was good for was getting knocked off, and landing on the floor, where it was often stepped on. So Max knocked the basket off, and then Stumpy stepped on it, putting his foot through the bottom with an unfortunate wicker-ripping sound. Max was worried for a second, but then his worry was eclipsed by the sight of Stumpy trying

to walk around the house with a basket stuck to his foot. Max laughed and laughed. Any reasonable person would see the humor in it.

“Are you going to be a freak all day?” Claire asked, suddenly standing over Max. “You’ve only been home for ten minutes.”

His sister Claire was fourteen, almost fifteen, and was no longer interested in Max, not on a consistent basis at least. Claire was a freshman now and the things they always liked to do together—including Wolf and Master, a game Max still thought worthy—were no longer so appealing to her. She had adopted a tone of perpetual dissatisfaction and annoyance with everything Max did, and with most things that existed in the world.

Max didn’t answer Claire’s question; any response would be problematic. If he said “No,” then it would imply he had been acting freakish, and if he said “Yes,” it would mean that not only had he been a freak, and he was admitting it, but that he intended to continue being a freak.

“You better make yourself scarce,” Claire said, repeating one of their dad’s favorite expressions. “I’m having people over.”

If Claire had been thinking clearly, she would have known that to tell Max to become scarce would only make him want to be more prominent, and to tell him that she was having people over would only make him more committed to being present. “Is Meika coming?” he asked. Meika was his favorite among Claire’s friends, the rest of whom were imbeciles. Meika paid attention to him, actually talked to him, asked him questions, had one time even come into his room to play Legos and admire the wolf suit he kept on his closet door. She had not forgotten what was fun.

“None of your business,” Claire said. “Just leave us alone, okay? Don’t ask them to play with your blocks or whatever lame crap you want them to do.”

Max knew that watching and annoying Claire and her friends would be better with someone else, so he went outside, got on his bike, and rode down the street to Clay’s. Clay was a new kid; he lived in one of the just-built houses down the street. And though he was pale and his head too big, Max was giving him a chance.

Max rode down the sidewalk serpentine-style, his head full of possibilities for what he and Clay might do with or, barring that, to Claire’s friends. It was December and the snow, dry and powdery just a few days earlier, was now melting, leaving slush on the roads and sidewalks, a patchy cover on the lawns.

Something was happening in Max’s neighborhood. The old houses were being taken down, and in their place, new, bigger and louder houses were rising. There were fourteen homes on his block, and in the last two years, six of them, all of them smallish, one-story ranches, had been leveled. In each case the same thing had happened: the owners had left or had died of old age, and the new owners had decided that they liked the location of the house, but wanted a far larger one where it stood. It brought to the neighborhood the constant sound of construction, and, thankfully for Max, a near-endless supply of castoff materials—nails, wood, wire, insulation, and tile. With it

all he’d been assembling a sort-of home of his own, in a

tree, in the woods by the lake.

Max pedaled up, dropped his bike, and knocked on the door of Clay Mahoney. He bent down to tie his shoes, and as he finished the second knot on his left shoe, the door flew open.

“Max?” Clay’s mother stood over him, wearing tight black pants and a small white T-shirt—TODAY! YES! It said—over a black lycra top; she was dressed like a competitive downhill skier. Behind her, an exercise video had been paused on the television. On the screen, three muscular women were reaching upward and rightward, desperate and grimacing, for something far beyond the frame.

“Is Clay home?” Max asked, standing up.

“No, I’m sorry Max, he’s not.”

She was holding a large, silver canister with a black handle—some sort of coffee mug—and while taking a sip from it, she looked around the front porch.

“Are you here alone?” she asked.

Max thought a second about this question, looking for a second meaning. Of course he was here alone.

“Yup,” he said.

She had a face, Max had noticed, that always seemed surprised. Her posture and voice aimed at knowingness, but her eyes said Really? What? How is that possible?

“How’d you get here?” she asked.

Another odd question. Max’s bike was lying no more than four feet behind him, in plain sight. Could she not see it?

“I rode,” he said, jerking a thumb over his shoulder.

“Alone?” she asked.

“Yup,” he said. This lady, Max thought.

“Alone?” she repeated. Her eyes had gone wide. Poor Clay. His mom was nuts. Max knew he should be careful about what he might say to a crazy person. Didn’t crazy people need to be treated with great care? He decided to be very polite.

“Yes, Mrs. Mahoney. I… am… alone.” He said the words slowly, carefully, maintaining eye contact all the while.

“Your parents let you ride around on your own? In December? Without a helmet?”

This lady definitely had a problem grasping the obvious. It was obvious that Max was alone, and obvious that he had ridden his bike. And there was nothing on his head, so why ask about the helmet? She was delusional on top of it all. Or maybe functionally blind?

“Yes, Mrs. Mahoney. I don’t need a helmet. I live just down the block. I rode here on the sidewalk.”

He pointed down the street to his own house, which was visible from her door. Mrs. Mahoney put her hand on her forehead and squinted, like a castaway searching the horizon for a rescue vessel. She dropped her hand, returned her eyes to Max, and sighed.

“Well, Clay is at his quilting class,” she said. Max didn’t know what a quilting class was, but it sounded a lot less fun than making icicle-spears and throwing them at birds, which had been on Max’s mind.

“Well, okay. Thanks, Mrs. Mahoney. Tell him I came by,” he said. He waved goodbye to Clay’s crazy mom, turned, and got on his bike. He heard the Mahoney’s door shut as he coasted away. But when he turned onto the sidewalk and toward his house, he found Mrs. Mahoney next to him, striding purposefully, still holding her silver drink canister.

“I can’t let you go alone,” she said, striding briskly alongside him.

“Thanks, Mrs. Mahoney, but I ride alone every day,” he said, pedaling cautiously and again maintaining steady eye contact. Her weirdness had tripled and his heartbeat had doubled.

“Not today you don’t,” she said, grabbing for the seat of Max’s bike.

Now he was getting scared. This woman was not only nuts, but she was following him, grabbing at him. He picked up speed. He figured he could ride faster than she could walk, and he intended to do so. He was now standing on his pedals.

She picked up her pace — still walking! Her elbows were flying left and right, her mouth a quick slash of determination. Was she smiling?

“Ha!” she giggled. “Fun!”

It was always the nuttiest people who smiled while doing the nuttiest things. This lady was far gone.

“Please,” he said, now pedaling as fast as he possibly could. He almost hit a mailbox, the Chungs’, the one bearing a large peace sign; this had caused great controversy in the neighborhood. “Just let me go,” he begged.

“Don’t worry,” she huffed, now at a full jog. “I’ll be right here the whole way.”

How could he shake her? Would she follow him inside his own house? She was no doubt waiting to get him alone and indoors, so she could do something to him. She could knock him cold with the coffee canister. Or maybe she’d grab a pillow, pin him down, and suffocate him? That seemed more her style. She had the clear-eyed, efficient look of a murderous nurse.

Now there was barking. Max turned to see that the Scolas’ dog had joined them, barking at Mrs. Mahoney and nipping her ankles. Mrs. Mahoney took little notice. Her eyes were bigger than ever. The exertion seemed to make her ever-more gleeful.

“Endorphins!” she sang. “Thanks, Max!”

“Please,” he said. “What are you gonna do to me?” It was about ten houses until his own.

“Keep you safe,” she said, “from all this.”

She waved her arm around, indicating the neighborhood that Max was born into and in which he’d been raised. It was a quiet street of tall elms and oaks, ending in a cul-de-sac. Beyond the cul-de-sac was a wooded few acres, then the lake. Nothing nefarious or of note had ever happened on this street, or in their town, or, for that matter, within four hundred miles.

Max swerved suddenly, leaving the sidewalk. Hejumped the curb into the road.

“The road!” Mrs. Mahoney gasped, as if he’d steered his bike into a river of molten lava. The road was empty now and was always empty. But soon she was right behind him, now running, again reaching for his seat.

Max decided it was silly to go home; that’s where she wanted him. He’d be trapped and she’d finish him for sure. His only chance of escape would be the forest.

He sped up again, giving himself enough room to turn around. He did a quick 180 and headed back toward the dead-end, hoping to make it to the woods.

“Where are you going?” she wailed.

Max almost laughed. She wouldn’t follow him into the

woods, would she? He looked back, and though she’d lost

a step or two, it wasn’t long before she was sprinting at

him. Man, she was fast! He was close to the road’s end,

almost at the trees.

“I won’t let you out of my sight!” she falsettoed. “Don’t worry!”

He jumped the curb again — eliciting a terrified howl

from Mrs. Mahoney — and jumbled over the rough grass

and snow. Soon he was quickly ducking under the first low

branches of the tall white-mustached pines, weaving

between the trunks.

“MAAAAAX!” she wailed. “Not the woods!”

He entered the forest and headed toward the ravine.

“Molesters! Drugs! Homeless! Needles!” she gasped.

The ravine was up ahead, about twenty feet deep and twelve feet wide. A month earlier, over the gap he’d put a wide bridge of plywood. If he could get to the gap, cross the bridge, and then pull the plank away in time, he might finally be free.

“Stop!” she yelled.

He swung his bike underneath him, left and right. He’d never ridden so fast. Even the Scola dog was having trouble keeping up; he was still yapping at the lady’s heels.

“Look out!” she screamed. “The what-do-you-call-it! The gorge!”

Duh, he thought. He made it to the bridge and again came a howl of incalculable terror. “Nooooooo!”

He rumbled quickly over the plank. On the other side, he spun out, dropped his bike, and grabbed the plywood. She was almost upon him when he pulled the board free. The bridge fell into the ravine and crashed against the rocks below.

She stopped short. “Dammit!” she yelled. She stood for a second, hands on hips, heaving. “How do you expect me to protect you when you’re all the way over there?”

Max thought of a few clever answers to this question, but instead said nothing. He mounted his bike again, in case Mrs. Mahoney decided to leap over the gap. She was far stronger and faster than he would have guessed, so he couldn’t rule it out.

At that moment, the Scolas’ dog, still running at full speed, chose to pass Mrs. Mahoney, jump over the ravine, and join Max. He flew, effortlessly, and landed on Max’s side. He turned back to face her, then looked up to Max with a toothy grin and happy eyes, as if the two of them had together vanquished a common enemy. Max laughed, and when the dog began barking at the woman doubled over on the edge of the ravine, Max barked, too. They both barked and barked and barked.

dog through the upstairs hallway, down the wooden stairs, and into the cold open foyer. Max and Stumpy did this often, running and wrestling through the house, though Max’s mother and sister, the two other occupants of the home, didn’t appreciate the volume and violence of the game. Max’s dad lived in the city and phoned on

Wednesdays and Sundays but sometimes did not.

Max lunged toward Stumpy, missed, barreled into the front door, and knocked the doorknob-basket off. The doorknob-basket was a small wicker vessel that Max thought was stupid but Max’s mom insisted on having on the front doorknob for good luck. The main thing the

basket was good for was getting knocked off, and landing on the floor, where it was often stepped on. So Max knocked the basket off, and then Stumpy stepped on it, putting his foot through the bottom with an unfortunate wicker-ripping sound. Max was worried for a second, but then his worry was eclipsed by the sight of Stumpy trying

to walk around the house with a basket stuck to his foot. Max laughed and laughed. Any reasonable person would see the humor in it.

“Are you going to be a freak all day?” Claire asked, suddenly standing over Max. “You’ve only been home for ten minutes.”

His sister Claire was fourteen, almost fifteen, and was no longer interested in Max, not on a consistent basis at least. Claire was a freshman now and the things they always liked to do together—including Wolf and Master, a game Max still thought worthy—were no longer so appealing to her. She had adopted a tone of perpetual dissatisfaction and annoyance with everything Max did, and with most things that existed in the world.

Max didn’t answer Claire’s question; any response would be problematic. If he said “No,” then it would imply he had been acting freakish, and if he said “Yes,” it would mean that not only had he been a freak, and he was admitting it, but that he intended to continue being a freak.

“You better make yourself scarce,” Claire said, repeating one of their dad’s favorite expressions. “I’m having people over.”

If Claire had been thinking clearly, she would have known that to tell Max to become scarce would only make him want to be more prominent, and to tell him that she was having people over would only make him more committed to being present. “Is Meika coming?” he asked. Meika was his favorite among Claire’s friends, the rest of whom were imbeciles. Meika paid attention to him, actually talked to him, asked him questions, had one time even come into his room to play Legos and admire the wolf suit he kept on his closet door. She had not forgotten what was fun.

“None of your business,” Claire said. “Just leave us alone, okay? Don’t ask them to play with your blocks or whatever lame crap you want them to do.”

Max knew that watching and annoying Claire and her friends would be better with someone else, so he went outside, got on his bike, and rode down the street to Clay’s. Clay was a new kid; he lived in one of the just-built houses down the street. And though he was pale and his head too big, Max was giving him a chance.

Max rode down the sidewalk serpentine-style, his head full of possibilities for what he and Clay might do with or, barring that, to Claire’s friends. It was December and the snow, dry and powdery just a few days earlier, was now melting, leaving slush on the roads and sidewalks, a patchy cover on the lawns.

Something was happening in Max’s neighborhood. The old houses were being taken down, and in their place, new, bigger and louder houses were rising. There were fourteen homes on his block, and in the last two years, six of them, all of them smallish, one-story ranches, had been leveled. In each case the same thing had happened: the owners had left or had died of old age, and the new owners had decided that they liked the location of the house, but wanted a far larger one where it stood. It brought to the neighborhood the constant sound of construction, and, thankfully for Max, a near-endless supply of castoff materials—nails, wood, wire, insulation, and tile. With it

all he’d been assembling a sort-of home of his own, in a

tree, in the woods by the lake.

Max pedaled up, dropped his bike, and knocked on the door of Clay Mahoney. He bent down to tie his shoes, and as he finished the second knot on his left shoe, the door flew open.

“Max?” Clay’s mother stood over him, wearing tight black pants and a small white T-shirt—TODAY! YES! It said—over a black lycra top; she was dressed like a competitive downhill skier. Behind her, an exercise video had been paused on the television. On the screen, three muscular women were reaching upward and rightward, desperate and grimacing, for something far beyond the frame.

“Is Clay home?” Max asked, standing up.

“No, I’m sorry Max, he’s not.”

She was holding a large, silver canister with a black handle—some sort of coffee mug—and while taking a sip from it, she looked around the front porch.

“Are you here alone?” she asked.

Max thought a second about this question, looking for a second meaning. Of course he was here alone.

“Yup,” he said.

She had a face, Max had noticed, that always seemed surprised. Her posture and voice aimed at knowingness, but her eyes said Really? What? How is that possible?

“How’d you get here?” she asked.

Another odd question. Max’s bike was lying no more than four feet behind him, in plain sight. Could she not see it?

“I rode,” he said, jerking a thumb over his shoulder.

“Alone?” she asked.

“Yup,” he said. This lady, Max thought.

“Alone?” she repeated. Her eyes had gone wide. Poor Clay. His mom was nuts. Max knew he should be careful about what he might say to a crazy person. Didn’t crazy people need to be treated with great care? He decided to be very polite.

“Yes, Mrs. Mahoney. I… am… alone.” He said the words slowly, carefully, maintaining eye contact all the while.

“Your parents let you ride around on your own? In December? Without a helmet?”

This lady definitely had a problem grasping the obvious. It was obvious that Max was alone, and obvious that he had ridden his bike. And there was nothing on his head, so why ask about the helmet? She was delusional on top of it all. Or maybe functionally blind?

“Yes, Mrs. Mahoney. I don’t need a helmet. I live just down the block. I rode here on the sidewalk.”

He pointed down the street to his own house, which was visible from her door. Mrs. Mahoney put her hand on her forehead and squinted, like a castaway searching the horizon for a rescue vessel. She dropped her hand, returned her eyes to Max, and sighed.

“Well, Clay is at his quilting class,” she said. Max didn’t know what a quilting class was, but it sounded a lot less fun than making icicle-spears and throwing them at birds, which had been on Max’s mind.

“Well, okay. Thanks, Mrs. Mahoney. Tell him I came by,” he said. He waved goodbye to Clay’s crazy mom, turned, and got on his bike. He heard the Mahoney’s door shut as he coasted away. But when he turned onto the sidewalk and toward his house, he found Mrs. Mahoney next to him, striding purposefully, still holding her silver drink canister.

“I can’t let you go alone,” she said, striding briskly alongside him.

“Thanks, Mrs. Mahoney, but I ride alone every day,” he said, pedaling cautiously and again maintaining steady eye contact. Her weirdness had tripled and his heartbeat had doubled.

“Not today you don’t,” she said, grabbing for the seat of Max’s bike.

Now he was getting scared. This woman was not only nuts, but she was following him, grabbing at him. He picked up speed. He figured he could ride faster than she could walk, and he intended to do so. He was now standing on his pedals.

She picked up her pace — still walking! Her elbows were flying left and right, her mouth a quick slash of determination. Was she smiling?

“Ha!” she giggled. “Fun!”

It was always the nuttiest people who smiled while doing the nuttiest things. This lady was far gone.

“Please,” he said, now pedaling as fast as he possibly could. He almost hit a mailbox, the Chungs’, the one bearing a large peace sign; this had caused great controversy in the neighborhood. “Just let me go,” he begged.

“Don’t worry,” she huffed, now at a full jog. “I’ll be right here the whole way.”

How could he shake her? Would she follow him inside his own house? She was no doubt waiting to get him alone and indoors, so she could do something to him. She could knock him cold with the coffee canister. Or maybe she’d grab a pillow, pin him down, and suffocate him? That seemed more her style. She had the clear-eyed, efficient look of a murderous nurse.

Now there was barking. Max turned to see that the Scolas’ dog had joined them, barking at Mrs. Mahoney and nipping her ankles. Mrs. Mahoney took little notice. Her eyes were bigger than ever. The exertion seemed to make her ever-more gleeful.

“Endorphins!” she sang. “Thanks, Max!”

“Please,” he said. “What are you gonna do to me?” It was about ten houses until his own.

“Keep you safe,” she said, “from all this.”

She waved her arm around, indicating the neighborhood that Max was born into and in which he’d been raised. It was a quiet street of tall elms and oaks, ending in a cul-de-sac. Beyond the cul-de-sac was a wooded few acres, then the lake. Nothing nefarious or of note had ever happened on this street, or in their town, or, for that matter, within four hundred miles.

Max swerved suddenly, leaving the sidewalk. Hejumped the curb into the road.

“The road!” Mrs. Mahoney gasped, as if he’d steered his bike into a river of molten lava. The road was empty now and was always empty. But soon she was right behind him, now running, again reaching for his seat.

Max decided it was silly to go home; that’s where she wanted him. He’d be trapped and she’d finish him for sure. His only chance of escape would be the forest.

He sped up again, giving himself enough room to turn around. He did a quick 180 and headed back toward the dead-end, hoping to make it to the woods.

“Where are you going?” she wailed.

Max almost laughed. She wouldn’t follow him into the

woods, would she? He looked back, and though she’d lost

a step or two, it wasn’t long before she was sprinting at

him. Man, she was fast! He was close to the road’s end,

almost at the trees.

“I won’t let you out of my sight!” she falsettoed. “Don’t worry!”

He jumped the curb again — eliciting a terrified howl

from Mrs. Mahoney — and jumbled over the rough grass

and snow. Soon he was quickly ducking under the first low

branches of the tall white-mustached pines, weaving

between the trunks.

“MAAAAAX!” she wailed. “Not the woods!”

He entered the forest and headed toward the ravine.

“Molesters! Drugs! Homeless! Needles!” she gasped.

The ravine was up ahead, about twenty feet deep and twelve feet wide. A month earlier, over the gap he’d put a wide bridge of plywood. If he could get to the gap, cross the bridge, and then pull the plank away in time, he might finally be free.

“Stop!” she yelled.

He swung his bike underneath him, left and right. He’d never ridden so fast. Even the Scola dog was having trouble keeping up; he was still yapping at the lady’s heels.

“Look out!” she screamed. “The what-do-you-call-it! The gorge!”

Duh, he thought. He made it to the bridge and again came a howl of incalculable terror. “Nooooooo!”

He rumbled quickly over the plank. On the other side, he spun out, dropped his bike, and grabbed the plywood. She was almost upon him when he pulled the board free. The bridge fell into the ravine and crashed against the rocks below.

She stopped short. “Dammit!” she yelled. She stood for a second, hands on hips, heaving. “How do you expect me to protect you when you’re all the way over there?”

Max thought of a few clever answers to this question, but instead said nothing. He mounted his bike again, in case Mrs. Mahoney decided to leap over the gap. She was far stronger and faster than he would have guessed, so he couldn’t rule it out.

At that moment, the Scolas’ dog, still running at full speed, chose to pass Mrs. Mahoney, jump over the ravine, and join Max. He flew, effortlessly, and landed on Max’s side. He turned back to face her, then looked up to Max with a toothy grin and happy eyes, as if the two of them had together vanquished a common enemy. Max laughed, and when the dog began barking at the woman doubled over on the edge of the ravine, Max barked, too. They both barked and barked and barked.

Recenzii

“Eggers, in this funny and touching novelization of Maurice Sendak’s picture book, is brilliant at portraying the exuberance and chaos of a young boy’s mind and heart.” —San Francisco Chronicle

“[A] terrific new novel. . . . A fresh way to tell us a story we already know so well, about the monstrous forces of love and hate that mark every childhood—and pursue us howling into adulthood.” —Boston Globe

“Dave Eggers has created a novel like childhood itself: sometimes weird, sometimes dark, and full of wonder.” —The Independent (London)

“Eggers strikes the perfect tone. . . . As Max navigates the politics of the island, the story gets progressively creepier, the Wild Things more impulsive, and the most dangerous thing Max can do is hurt someone’s feelings. It’s still Eggers, so that means the humor will always be there in the dark.” —Time Out Chicago

“Deeply imaginative, slightly strange, occasionally dark, and ultimately touching. . . . The writing is crisp and alive, and it works, perhaps better than an adaptation ever should.” —Flavorwire

“Like the original, this is far from the cozy world kids are often fed, but it has real heart—Eggers uses simple but superbly effective prose to suggest that childhood has to be lived without cosseting for us to grow up with any semblance of a normal personality.” —The Independent (London)

“A wonderful read. . . . Eggers makes us privy to Max’s thoughts, fears and desires. He lets us feel the boy’s confusion as anger results in shocking behavior (Max bites his mother’s arm); we feel the rush of being the aggressor in battle and subsequent shame of having inflicted pain; the release of a full-throated howl; the fear of abandonment; the sadness of leaving; the joy of knowing you belong. And we get to know the Wild Things as individuals.” —Montreal Gazette

“Eggers does a fine job portraying the chaotic existence of a very young boy, as well as the innumerable stresses the rest of the world places on him without even thinking.” —The Guardian (London)

“There is probably no cooler figure in American letters than Eggers: his prose is luminous, playful, original.” —The Times (London)

“Everything is in the spirit of Sendak’s book. There are knowing nods—Max carves his name on the boat during the boring trip to the island—and the monsters retain their utter, incomprehensible difference. There is far more emotion: the monsters are petulant, panicky, selfish, vulnerable and violent. . . . The parting is affecting. It won’t just be Max and the monsters that end in a mess of tears.” —The Scotsman

“[A] terrific new novel. . . . A fresh way to tell us a story we already know so well, about the monstrous forces of love and hate that mark every childhood—and pursue us howling into adulthood.” —Boston Globe

“Dave Eggers has created a novel like childhood itself: sometimes weird, sometimes dark, and full of wonder.” —The Independent (London)

“Eggers strikes the perfect tone. . . . As Max navigates the politics of the island, the story gets progressively creepier, the Wild Things more impulsive, and the most dangerous thing Max can do is hurt someone’s feelings. It’s still Eggers, so that means the humor will always be there in the dark.” —Time Out Chicago

“Deeply imaginative, slightly strange, occasionally dark, and ultimately touching. . . . The writing is crisp and alive, and it works, perhaps better than an adaptation ever should.” —Flavorwire

“Like the original, this is far from the cozy world kids are often fed, but it has real heart—Eggers uses simple but superbly effective prose to suggest that childhood has to be lived without cosseting for us to grow up with any semblance of a normal personality.” —The Independent (London)

“A wonderful read. . . . Eggers makes us privy to Max’s thoughts, fears and desires. He lets us feel the boy’s confusion as anger results in shocking behavior (Max bites his mother’s arm); we feel the rush of being the aggressor in battle and subsequent shame of having inflicted pain; the release of a full-throated howl; the fear of abandonment; the sadness of leaving; the joy of knowing you belong. And we get to know the Wild Things as individuals.” —Montreal Gazette

“Eggers does a fine job portraying the chaotic existence of a very young boy, as well as the innumerable stresses the rest of the world places on him without even thinking.” —The Guardian (London)

“There is probably no cooler figure in American letters than Eggers: his prose is luminous, playful, original.” —The Times (London)

“Everything is in the spirit of Sendak’s book. There are knowing nods—Max carves his name on the boat during the boring trip to the island—and the monsters retain their utter, incomprehensible difference. There is far more emotion: the monsters are petulant, panicky, selfish, vulnerable and violent. . . . The parting is affecting. It won’t just be Max and the monsters that end in a mess of tears.” —The Scotsman