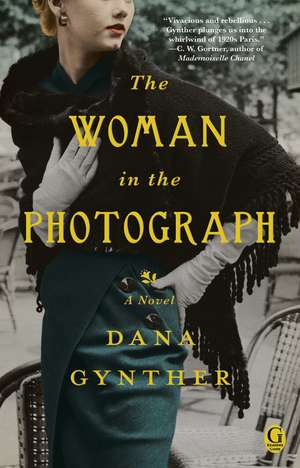

The Woman in the Photograph

Autor Dana Gyntheren Limba Engleză Paperback – 10 sep 2015

Coming into her own more fully every day, Lee models, begins working on her own projects, and even stars in a film, provoking the jealousy of the older and possessive Man Ray. Drinking and carousing is the order of the day, but while hobnobbing with the likes of Picasso and Charlie Chaplin, she also falls in love with the art of photography and finds that her own vision can no longer come second to her mentor's.

The Woman in the Photograph is the richly drawn, tempestuous novel about a talented and fearless young woman caught up in one of the most fascinating times of the twentieth century.

Preț: 123.63 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 185

Preț estimativ în valută:

23.66€ • 24.61$ • 19.53£

23.66€ • 24.61$ • 19.53£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 25 martie-08 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781476731957

ISBN-10: 1476731950

Pagini: 352

Dimensiuni: 135 x 210 x 43 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Editura: Gallery Books

Colecția Gallery Books

ISBN-10: 1476731950

Pagini: 352

Dimensiuni: 135 x 210 x 43 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Editura: Gallery Books

Colecția Gallery Books

Notă biografică

Dana Gynther was raised in St. Louis, Missouri, and Auburn, Alabama. She has an MA in French Literature from the University of Alabama. She has lived in France and currently lives in Valencia, Spain, where she and her husband work as teachers and translators. They have two daughters and an extremely vocal cat.

Extras

The Woman in the Photograph

![]()

Lips pressed together in concentration, Lee sat under a gas lamp at a wooden table, tracing over a penciled design in India ink. With deliberate strokes, she colored in the dark spaces around a stylized artichoke, the central detail of a High Renaissance hat. She was finishing off her first batch of fashionworthy patterns—sketches made in the dim light of the Uffizi Gallery and Pitti Palace, then inked over at the pensione—and was eager to send it to New York and be rid of it.

“Hello there.” Tanja breezed into their room, a knitted shopping bag over her shoulder, a fresh loaf of filone sticking out of the top. She peeked down at Lee’s drawing. “What are you working on?”

“A hat I found yesterday in Perugino’s The Lamentation over the Dead Christ. It made me laugh.” She carefully blew on it, then picked it up to show Tanja. “I mean, look at it! More than a hat, it looks like the tattooed skull of a sailor, like the head of Ishmael’s buddy in Moby-Dick.” She set it back on the table with a small snort. “I thought it was funny—imagining the chic ladies of Manhattan strutting around in hats like these—until I started tracing it. It’s a pain in the neck! I can’t believe I agreed to this ridiculous job.”

“You need a break. Are you hungry? I bought some of that chicken-liver pâté you like. The one with capers and anchovies.”

“Wonderful.”

Lee stood up to stow away her things, to make room at their only table. Slowly guiding her finished drawings into the cardboard portfolio, she knocked over the ink. Deep black seeped across the oak like an evil spirit, onto her cigarettes and over her sketchbook. “Damn it to hell! Grab a towel, a rag, something—”

Tanja snatched the Guardian off her bed, one week old and twice read, and handed it to Lee, who crumpled it to soak up the ink with newsprint.

“Shit, I think I’ve got some on my dress.”

“Who wears ecru to work with India ink?” Tanja muttered, a loud aside.

“Who comes to Florence to work at all?” Lee pitched the soggy newspaper into the bin, then rinsed her hands in the basin in the corner. She examined her knee-length dress, staring down at the spattering of tiny black flecks on the hem of pale brown chiffon. She shrugged—“Not a bad look”—then turned back to Tanja.

“Let’s get out of here and get a drink. I’m desperate for some air.”

They left their dark pensione on the via Porta Rossa and strolled over to the sunlit Piazza della Signoria, the city’s beating heart. In the two weeks they’d been in Florence, they had become habitués of a few local cafés, where the flirty barmen and waiters remembered their names and preferences. Heads always turned as the two slender, short-haired models—one dark, one fair—walked by.

“Lee, Tanja! Le bellissime ragazze!” The awkward youth, his hair slicked back with pomade, his waist cinched in by the strings of a white apron, was quickly joined by an older waiter, whose smile was equally large.

“Sit, sit! Chianti, no?” The older one asked, his limited English the better of the two. “Cold?”

“Si, grazie,” Lee answered. She had picked up a handful of phrases since they’d been in Italy, but was looking forward to being back in France, where she could truly speak the language and not just pretend.

Sitting back with closed eyes, her bare arms soaking up the sun, she tried to think of ways to get out of her research assignment. Would the seven completed drawings be enough? Maybe she could claim tuberculosis, malaria, the plague? Or that she was kidnapped by gypsies? Perhaps Tanja could write a letter for her, saying she’d lost all the feeling in her hands?

The older waiter ceremonially served the wine as the younger one slid a generous plate of almonds to the center of their table. “For you,” he managed.

Lee raised her glass to them with a tired smile, then took a long sip.

“Oh, Tanja, I’m so fed up with these stupid designs.”

“I have some news that might make you feel better. I’ve seen Mr. Porter this morning—”

“Hooray,” Lee broke in, her deadpan voice oozing sarcasm.

Before their departure, Tanja’s grandfather had somehow procured a letter of introduction to an elderly art dealer, Bancroft Porter, one of Florence’s fin de siècle English expatriates and a lifelong bachelor. Since their first meeting the week before, they’d been saddled with him every day; he’d insisted on showing them every last monument, statue, painting—hell, every last rock in the city. Mr. Porter fancied himself their guide and chaperone, but Lee suspected what he really liked was the good-looking boys they attracted.

“Really, Tanja, not Mr. Porter again,” Lee continued, pouring herself another glass. “He reminds me of that art history professor back at the League. What was his name? Dr. Rowell! Remember him, with his jowly drone and never-ending lists of dates?” Lee affected a whiney monotone, “And this master, from 1443 to 1497, used walnut oil to—”

“Oh, Lee, he’s not that bad,” Tanja began, then giggled. “Well, almost. But today he told me that he’s managed to get us into Bernard Berenson’s salon this afternoon.” She beamed at Lee with expectation, but was met with a blank stare. “You know, the historian and critic, the man museums turn to if they’re not sure a piece is authentic? Mr. Porter says Berenson is the leading expert on Renaissance art in the world.”

“Not more Renaissance art! Tanja, I’ve had it up to here.” Tipsy, she flung her hand over her head, nearly hitting a passing waiter. “All of these old expats are the same. Stodgy, self-satisfied, and, well, boring. Like characters out of a Henry James novel. I’d rather spend the afternoon on my own than with them.”

“Working?” Tanja threw her an incredulous look.

“Of course not.”

Feeling the wine move from her empty stomach straight to her head, Lee scooped up a handful of almonds and tipped them into her mouth. Crunching, she gazed around the large square: a horse-drawn cart laden with tomatoes clopped along the ancient brick pavement, past grandiose palazzos and tall, narrow houses; young men lounging under the arcades called out to a trio of girls scurrying off to mass with heads covered in black lace; two clusters of plump, pink tourists—British? or Germans, more like—studied the open-air statues. One lot was peeking up at a marble woman being violently abducted, shading their eyes with Baedeker guidebooks while trying to ignore the hopeful beggars orbiting around them with shy, half-opened hands; the other, at the foot of an equestrian Medici, was swatting away a persistent souvenir vendor. He turned around in frustration and caught Lee’s roving eye. With a professional smile, he made a beeline toward her. He rushed across the square, his arms stretched out to unfold an accordion of cardboard photographs tied together with a glossy red ribbon.

“Signorina.” Nearly breathless, he thrust the clumsily sewn book of picture postcards before her. “Bellissime fotografie.”

Lee glanced down at the gray churches, towers, and panoramic views and shook her head.

“No, grazie.”

“Cinque lire. Molto economico,” he insisted, pushing the photos toward her again.

The older waiter bustled over and growled at the vendor and—after a few staccato hand gestures—he left.

“That’s what I’ll do today.” Lee’s mood lightened swiftly. “Take some photos. Unfold the ol’ Kodak. See if I can take one original shot of this place, find one angle that hasn’t been made into a postcard.”

“Well, it’s up to you. I’m going to go meet Bernard Berenson.”

Lee grinned at her friend. “Have fun, sweetheart.”

• • •

That afternoon, after a heavy siesta, Lee pulled her camera down from the shelf on the wardrobe. She hadn’t taken any photos since their crossing; a roll of six of the two of them—drinking cocktails on deck chairs, hamming it up with lifebuoy rings, peeking into funnels—had come out overexposed and slightly out of focus. Maybe the martinis were to blame? She put in a fresh roll, determined to do better this time around. Her father, an engineer, had a passion for photography—he even had his own darkroom—and Lee knew she’d inherited his tinker’s soul.

With one last glare at the worktable—the empty glass bottle sat next to the ink stain, innocent as poison—she checked herself in the mirror, adjusted the brim of her crinoline sun hat, and headed back to the square.

Now the buttery light came down in a slant, casting interesting shadows. Looking for inspiration, she studied various statues, hoping she didn’t look as slack-jawed and dull as the morning’s Germans. Her camera at her chest, she peered into the viewfinder: David, Hercules, Perseus, Neptune. Each time, she found her gaze drifting down to their groins. Lee hadn’t been with a man since the night before they boarded ship in New York: she missed the heat, excitement, adventure. Looking down at the camera, her face safely hidden by her hat, she smiled to herself, comparing these bronze and marble bodies to ones she had known, tempted to make a photo series of Renaissance penises.

On the pedestal of the Hercules statue, heads of wild beasts adorned every corner. Lee noticed that, from an angle, the wolf’s head looked like it wanted to bite a statue in an arcade behind it. Thinking it a clever shot, she tried to focus, but when the foreground was sharp, the background looked blurry. Sure her father would have known how to fix it, she grudgingly took the shot anyway. Maybe the figure would look like he was running away?

Lee went around the square and took more close-ups of statues from unusual positions: Neptune’s horses seemed to spit, Perseus’s winged sandals became hideous birds. Looking back at the sandals, she wondered whether those might make a splash in New York. Poolside languid ladies, poised to take flight at any moment. Should she draw them, as well? Or, perhaps she could just send the photo? Suddenly, it dawned on her. There was no need to spend hours making tedious sketches or tracing fine lines with that treacherous ink. She could let the machine do the work!

Lee held up her camera and kissed it.

For the next two weeks, Lee tinkered with taking photos in art galleries. It was much easier than drawing, but it was still a challenge. Capturing details—the Florentine patterns, the jewelry, the belts and ribbons—with low-speed film in gloomy, windowless rooms required a level of skill far beyond that of the typical Kodak Girl. But it was a challenge she enjoyed. She bought a tripod, which proved so flimsy that she had to anchor it down with an umbrella, and stationed herself in front of canvases like Botticelli’s Primavera and Titian’s La Bella, adjusting the light and toying with distance until she got it right. Finally, she had amassed enough successful prints to satisfy any employer.

Though still a novice, Lee had decided that photography was the art for her.

• • •

“Tanja, do you really want to spend our last night in Florence with Mr. Porter and his lot?”

Lee was sitting on her packed trunk, buckling her shoes.

“It’s a soirée in our honor. I think it’s sweet.” Tanja screwed on a pair of earrings, then gently powder-puffed her face. “And we haven’t met anyone else we can have a proper conversation with—”

“Proper is the word for it. What I’d give for a few dirty jokes.”

“I’m sure you’ll get plenty of that in Paris. Those bohemians in Montparnasse should keep you entertained.” Tanja smiled at her. “Have you decided yet what you’re going to do there?”

“I’ll think of something.”

That evening, in Bancroft Porter’s nineteenth-century dining room, Lee barely listened to the discussion about servants and other local riffraff, but glanced around at the three other guests. Lord Rukin dominated the table with his loud voice and pre-war mustache while Lady Rukin, at Lee’s side, sat silently, pulling her shoulder blades forward with the determination of a footbinder, trying to make her ample bosom as concave as possible. The other guest, a Mr. Larsen from Copenhagen, pale and effete, was a newcomer to Florence. The obliging Mr. Porter would surely take him under his wing; hiding a smirk behind her napkin, Lee supposed he would prove a much more satisfactory protégé than she and Tanja had.

At the end of the meal, the company made their way to the salon, where the much-discussed Italian maids laid out a variety of after-dinner options—fresh figs and apricots, crunchy biscotti, grappa and amaretto—and disappeared.

“Since it is Tanja and Lee’s last night among us, I have hired some entertainment. A string quartet to play the highlights from Tosca.” Mr. Porter, delighted with himself, swept an arm toward the door, where the black-tied musicians were waiting to enter. “My poor girls, after you leave Italy, you’ll be hard pressed to find music like this.”

Preferring Puccini to vapid conversation, Lee settled back in the fussy armchair with a glass of grappa, but as the musicians launched into an instrumental aria, her mind began to wander. Her eyes flitted around the room, from the antiquated guests to the gilded harpsichord to the ceramic figurines and shadowy landscapes; she wondered how difficult it would be to take photographs in there. Her eyes returned to rest on the pear-shaped violinist, whose back was to her. Lips curling into a smile, she thought again of Man Ray.

Ever since Edward Steichen had shown her Noire et Blanche, she’d been intrigued by him. After that shoot, back at the Vogue offices, she’d asked staffers if they could lay their hands on any more of his work. The image they’d found floored her: an armless woman whose back was pierced with the f-holes of a violin, her curves becoming those of the instrument. Another clean shot, both beautiful and utterly disturbing. She narrowed her eyes, trying to imagine the body of this bottom-heavy musician transforming into his violin. She let out a sigh. This stale old room just didn’t have the Man Ray magic.

During that last week in New York, she had taken advantage of her good-bye dinners and parties to try to get the scoop on him. She found that most of the artists and writers she knew (and even some of the café-society elite) had heard of him, but they only had the barest facts: Mr. Ray was from Brooklyn but had lived in Paris for nearly a decade; he was one of those avant-garde (or “gaga,” according to one source) Surrealists: artists so fascinated by the subconscious, they tried to paint their dreams. And the woman in the photographs? Most everyone agreed she was his lover and muse. One man identified her as a cabaret singer named Kiki. Just Kiki.

Lee had had the vague notion that, once in Paris, she would meet him or even model for him. That maybe she could pose for one of his brilliant ideas. But in the last two weeks, she’d begun to wonder if it was time to step behind the camera. Not only was she bored of having her picture taken, but she’d enjoyed the innovative headwork of taking photos, even of dull design details made under adverse conditions.

Listening to the swell of voiceless opera, she felt inspired. Man Ray could teach her how to be a real photographer. She was interested in his aesthetic—so creative and sexy—but also his technique. By all accounts, he was the most interesting, the most influential, the most daring photographer in Paris. Why learn the craft from anyone else? She quietly toasted the idea with a healthy sip of grappa.

Walking back to the pensione after the soirée, Lee took Tanja’s hand in her own. “Well, that was worthwhile.”

“You enjoyed it? I can’t believe it. The ongoing woes of Lord and Lady Bumpkin and that scaredy-cat Mr. How-terribly-frightful?” She gave Lee a sidelong glance. “During the music, you looked like you were in a trance. I thought the voice of my dead Aunt Mabel was going to come out of your mouth.”

Lee laughed. “I was in a trance. I’ve finally decided what to do when I hit Paris.”

“What’s that?”

“I’m going to take photography lessons from Man Ray.”

“The Surrealist? What makes you think he’s going to teach you?”

“Well, why wouldn’t he?”

I

Lips pressed together in concentration, Lee sat under a gas lamp at a wooden table, tracing over a penciled design in India ink. With deliberate strokes, she colored in the dark spaces around a stylized artichoke, the central detail of a High Renaissance hat. She was finishing off her first batch of fashionworthy patterns—sketches made in the dim light of the Uffizi Gallery and Pitti Palace, then inked over at the pensione—and was eager to send it to New York and be rid of it.

“Hello there.” Tanja breezed into their room, a knitted shopping bag over her shoulder, a fresh loaf of filone sticking out of the top. She peeked down at Lee’s drawing. “What are you working on?”

“A hat I found yesterday in Perugino’s The Lamentation over the Dead Christ. It made me laugh.” She carefully blew on it, then picked it up to show Tanja. “I mean, look at it! More than a hat, it looks like the tattooed skull of a sailor, like the head of Ishmael’s buddy in Moby-Dick.” She set it back on the table with a small snort. “I thought it was funny—imagining the chic ladies of Manhattan strutting around in hats like these—until I started tracing it. It’s a pain in the neck! I can’t believe I agreed to this ridiculous job.”

“You need a break. Are you hungry? I bought some of that chicken-liver pâté you like. The one with capers and anchovies.”

“Wonderful.”

Lee stood up to stow away her things, to make room at their only table. Slowly guiding her finished drawings into the cardboard portfolio, she knocked over the ink. Deep black seeped across the oak like an evil spirit, onto her cigarettes and over her sketchbook. “Damn it to hell! Grab a towel, a rag, something—”

Tanja snatched the Guardian off her bed, one week old and twice read, and handed it to Lee, who crumpled it to soak up the ink with newsprint.

“Shit, I think I’ve got some on my dress.”

“Who wears ecru to work with India ink?” Tanja muttered, a loud aside.

“Who comes to Florence to work at all?” Lee pitched the soggy newspaper into the bin, then rinsed her hands in the basin in the corner. She examined her knee-length dress, staring down at the spattering of tiny black flecks on the hem of pale brown chiffon. She shrugged—“Not a bad look”—then turned back to Tanja.

“Let’s get out of here and get a drink. I’m desperate for some air.”

They left their dark pensione on the via Porta Rossa and strolled over to the sunlit Piazza della Signoria, the city’s beating heart. In the two weeks they’d been in Florence, they had become habitués of a few local cafés, where the flirty barmen and waiters remembered their names and preferences. Heads always turned as the two slender, short-haired models—one dark, one fair—walked by.

“Lee, Tanja! Le bellissime ragazze!” The awkward youth, his hair slicked back with pomade, his waist cinched in by the strings of a white apron, was quickly joined by an older waiter, whose smile was equally large.

“Sit, sit! Chianti, no?” The older one asked, his limited English the better of the two. “Cold?”

“Si, grazie,” Lee answered. She had picked up a handful of phrases since they’d been in Italy, but was looking forward to being back in France, where she could truly speak the language and not just pretend.

Sitting back with closed eyes, her bare arms soaking up the sun, she tried to think of ways to get out of her research assignment. Would the seven completed drawings be enough? Maybe she could claim tuberculosis, malaria, the plague? Or that she was kidnapped by gypsies? Perhaps Tanja could write a letter for her, saying she’d lost all the feeling in her hands?

The older waiter ceremonially served the wine as the younger one slid a generous plate of almonds to the center of their table. “For you,” he managed.

Lee raised her glass to them with a tired smile, then took a long sip.

“Oh, Tanja, I’m so fed up with these stupid designs.”

“I have some news that might make you feel better. I’ve seen Mr. Porter this morning—”

“Hooray,” Lee broke in, her deadpan voice oozing sarcasm.

Before their departure, Tanja’s grandfather had somehow procured a letter of introduction to an elderly art dealer, Bancroft Porter, one of Florence’s fin de siècle English expatriates and a lifelong bachelor. Since their first meeting the week before, they’d been saddled with him every day; he’d insisted on showing them every last monument, statue, painting—hell, every last rock in the city. Mr. Porter fancied himself their guide and chaperone, but Lee suspected what he really liked was the good-looking boys they attracted.

“Really, Tanja, not Mr. Porter again,” Lee continued, pouring herself another glass. “He reminds me of that art history professor back at the League. What was his name? Dr. Rowell! Remember him, with his jowly drone and never-ending lists of dates?” Lee affected a whiney monotone, “And this master, from 1443 to 1497, used walnut oil to—”

“Oh, Lee, he’s not that bad,” Tanja began, then giggled. “Well, almost. But today he told me that he’s managed to get us into Bernard Berenson’s salon this afternoon.” She beamed at Lee with expectation, but was met with a blank stare. “You know, the historian and critic, the man museums turn to if they’re not sure a piece is authentic? Mr. Porter says Berenson is the leading expert on Renaissance art in the world.”

“Not more Renaissance art! Tanja, I’ve had it up to here.” Tipsy, she flung her hand over her head, nearly hitting a passing waiter. “All of these old expats are the same. Stodgy, self-satisfied, and, well, boring. Like characters out of a Henry James novel. I’d rather spend the afternoon on my own than with them.”

“Working?” Tanja threw her an incredulous look.

“Of course not.”

Feeling the wine move from her empty stomach straight to her head, Lee scooped up a handful of almonds and tipped them into her mouth. Crunching, she gazed around the large square: a horse-drawn cart laden with tomatoes clopped along the ancient brick pavement, past grandiose palazzos and tall, narrow houses; young men lounging under the arcades called out to a trio of girls scurrying off to mass with heads covered in black lace; two clusters of plump, pink tourists—British? or Germans, more like—studied the open-air statues. One lot was peeking up at a marble woman being violently abducted, shading their eyes with Baedeker guidebooks while trying to ignore the hopeful beggars orbiting around them with shy, half-opened hands; the other, at the foot of an equestrian Medici, was swatting away a persistent souvenir vendor. He turned around in frustration and caught Lee’s roving eye. With a professional smile, he made a beeline toward her. He rushed across the square, his arms stretched out to unfold an accordion of cardboard photographs tied together with a glossy red ribbon.

“Signorina.” Nearly breathless, he thrust the clumsily sewn book of picture postcards before her. “Bellissime fotografie.”

Lee glanced down at the gray churches, towers, and panoramic views and shook her head.

“No, grazie.”

“Cinque lire. Molto economico,” he insisted, pushing the photos toward her again.

The older waiter bustled over and growled at the vendor and—after a few staccato hand gestures—he left.

“That’s what I’ll do today.” Lee’s mood lightened swiftly. “Take some photos. Unfold the ol’ Kodak. See if I can take one original shot of this place, find one angle that hasn’t been made into a postcard.”

“Well, it’s up to you. I’m going to go meet Bernard Berenson.”

Lee grinned at her friend. “Have fun, sweetheart.”

• • •

That afternoon, after a heavy siesta, Lee pulled her camera down from the shelf on the wardrobe. She hadn’t taken any photos since their crossing; a roll of six of the two of them—drinking cocktails on deck chairs, hamming it up with lifebuoy rings, peeking into funnels—had come out overexposed and slightly out of focus. Maybe the martinis were to blame? She put in a fresh roll, determined to do better this time around. Her father, an engineer, had a passion for photography—he even had his own darkroom—and Lee knew she’d inherited his tinker’s soul.

With one last glare at the worktable—the empty glass bottle sat next to the ink stain, innocent as poison—she checked herself in the mirror, adjusted the brim of her crinoline sun hat, and headed back to the square.

Now the buttery light came down in a slant, casting interesting shadows. Looking for inspiration, she studied various statues, hoping she didn’t look as slack-jawed and dull as the morning’s Germans. Her camera at her chest, she peered into the viewfinder: David, Hercules, Perseus, Neptune. Each time, she found her gaze drifting down to their groins. Lee hadn’t been with a man since the night before they boarded ship in New York: she missed the heat, excitement, adventure. Looking down at the camera, her face safely hidden by her hat, she smiled to herself, comparing these bronze and marble bodies to ones she had known, tempted to make a photo series of Renaissance penises.

On the pedestal of the Hercules statue, heads of wild beasts adorned every corner. Lee noticed that, from an angle, the wolf’s head looked like it wanted to bite a statue in an arcade behind it. Thinking it a clever shot, she tried to focus, but when the foreground was sharp, the background looked blurry. Sure her father would have known how to fix it, she grudgingly took the shot anyway. Maybe the figure would look like he was running away?

Lee went around the square and took more close-ups of statues from unusual positions: Neptune’s horses seemed to spit, Perseus’s winged sandals became hideous birds. Looking back at the sandals, she wondered whether those might make a splash in New York. Poolside languid ladies, poised to take flight at any moment. Should she draw them, as well? Or, perhaps she could just send the photo? Suddenly, it dawned on her. There was no need to spend hours making tedious sketches or tracing fine lines with that treacherous ink. She could let the machine do the work!

Lee held up her camera and kissed it.

For the next two weeks, Lee tinkered with taking photos in art galleries. It was much easier than drawing, but it was still a challenge. Capturing details—the Florentine patterns, the jewelry, the belts and ribbons—with low-speed film in gloomy, windowless rooms required a level of skill far beyond that of the typical Kodak Girl. But it was a challenge she enjoyed. She bought a tripod, which proved so flimsy that she had to anchor it down with an umbrella, and stationed herself in front of canvases like Botticelli’s Primavera and Titian’s La Bella, adjusting the light and toying with distance until she got it right. Finally, she had amassed enough successful prints to satisfy any employer.

Though still a novice, Lee had decided that photography was the art for her.

• • •

“Tanja, do you really want to spend our last night in Florence with Mr. Porter and his lot?”

Lee was sitting on her packed trunk, buckling her shoes.

“It’s a soirée in our honor. I think it’s sweet.” Tanja screwed on a pair of earrings, then gently powder-puffed her face. “And we haven’t met anyone else we can have a proper conversation with—”

“Proper is the word for it. What I’d give for a few dirty jokes.”

“I’m sure you’ll get plenty of that in Paris. Those bohemians in Montparnasse should keep you entertained.” Tanja smiled at her. “Have you decided yet what you’re going to do there?”

“I’ll think of something.”

That evening, in Bancroft Porter’s nineteenth-century dining room, Lee barely listened to the discussion about servants and other local riffraff, but glanced around at the three other guests. Lord Rukin dominated the table with his loud voice and pre-war mustache while Lady Rukin, at Lee’s side, sat silently, pulling her shoulder blades forward with the determination of a footbinder, trying to make her ample bosom as concave as possible. The other guest, a Mr. Larsen from Copenhagen, pale and effete, was a newcomer to Florence. The obliging Mr. Porter would surely take him under his wing; hiding a smirk behind her napkin, Lee supposed he would prove a much more satisfactory protégé than she and Tanja had.

At the end of the meal, the company made their way to the salon, where the much-discussed Italian maids laid out a variety of after-dinner options—fresh figs and apricots, crunchy biscotti, grappa and amaretto—and disappeared.

“Since it is Tanja and Lee’s last night among us, I have hired some entertainment. A string quartet to play the highlights from Tosca.” Mr. Porter, delighted with himself, swept an arm toward the door, where the black-tied musicians were waiting to enter. “My poor girls, after you leave Italy, you’ll be hard pressed to find music like this.”

Preferring Puccini to vapid conversation, Lee settled back in the fussy armchair with a glass of grappa, but as the musicians launched into an instrumental aria, her mind began to wander. Her eyes flitted around the room, from the antiquated guests to the gilded harpsichord to the ceramic figurines and shadowy landscapes; she wondered how difficult it would be to take photographs in there. Her eyes returned to rest on the pear-shaped violinist, whose back was to her. Lips curling into a smile, she thought again of Man Ray.

Ever since Edward Steichen had shown her Noire et Blanche, she’d been intrigued by him. After that shoot, back at the Vogue offices, she’d asked staffers if they could lay their hands on any more of his work. The image they’d found floored her: an armless woman whose back was pierced with the f-holes of a violin, her curves becoming those of the instrument. Another clean shot, both beautiful and utterly disturbing. She narrowed her eyes, trying to imagine the body of this bottom-heavy musician transforming into his violin. She let out a sigh. This stale old room just didn’t have the Man Ray magic.

During that last week in New York, she had taken advantage of her good-bye dinners and parties to try to get the scoop on him. She found that most of the artists and writers she knew (and even some of the café-society elite) had heard of him, but they only had the barest facts: Mr. Ray was from Brooklyn but had lived in Paris for nearly a decade; he was one of those avant-garde (or “gaga,” according to one source) Surrealists: artists so fascinated by the subconscious, they tried to paint their dreams. And the woman in the photographs? Most everyone agreed she was his lover and muse. One man identified her as a cabaret singer named Kiki. Just Kiki.

Lee had had the vague notion that, once in Paris, she would meet him or even model for him. That maybe she could pose for one of his brilliant ideas. But in the last two weeks, she’d begun to wonder if it was time to step behind the camera. Not only was she bored of having her picture taken, but she’d enjoyed the innovative headwork of taking photos, even of dull design details made under adverse conditions.

Listening to the swell of voiceless opera, she felt inspired. Man Ray could teach her how to be a real photographer. She was interested in his aesthetic—so creative and sexy—but also his technique. By all accounts, he was the most interesting, the most influential, the most daring photographer in Paris. Why learn the craft from anyone else? She quietly toasted the idea with a healthy sip of grappa.

Walking back to the pensione after the soirée, Lee took Tanja’s hand in her own. “Well, that was worthwhile.”

“You enjoyed it? I can’t believe it. The ongoing woes of Lord and Lady Bumpkin and that scaredy-cat Mr. How-terribly-frightful?” She gave Lee a sidelong glance. “During the music, you looked like you were in a trance. I thought the voice of my dead Aunt Mabel was going to come out of your mouth.”

Lee laughed. “I was in a trance. I’ve finally decided what to do when I hit Paris.”

“What’s that?”

“I’m going to take photography lessons from Man Ray.”

“The Surrealist? What makes you think he’s going to teach you?”

“Well, why wouldn’t he?”

Recenzii

"An intriguing, elegant novel. Dana Gynther's portrayal of Lee Miller's fascinating life in 1920s Paris makes for compelling reading."

“By turns glamorous and brilliant, tender and tenacious, Lee Miller captured hearts with her photographs and her vibrant persona. Dana Gynther brings the story of the incomparable beauty and her tumultuous relationship with artist Man Ray to vivid life in her latest novel, The Woman in the Photograph.”

"Vivacious and rebellious, Lee Miller strides across the pages of The Woman in the Photograph with her inimitable style. From artistic garrets to Man Ray's photography studio to the elite offices of Vogue, Dana Gynther plunges us into the whirlwind of 1920s Paris."

“Gynther captures the naughty, bawdy ‘20s to perfection with her large and colorful cast of characters… Art and the creative process are at the heart of Gynther’s novel, along with portraits of people we wish to know and a story for readers to devour.”

“By turns glamorous and brilliant, tender and tenacious, Lee Miller captured hearts with her photographs and her vibrant persona. Dana Gynther brings the story of the incomparable beauty and her tumultuous relationship with artist Man Ray to vivid life in her latest novel, The Woman in the Photograph.”

"Vivacious and rebellious, Lee Miller strides across the pages of The Woman in the Photograph with her inimitable style. From artistic garrets to Man Ray's photography studio to the elite offices of Vogue, Dana Gynther plunges us into the whirlwind of 1920s Paris."

“Gynther captures the naughty, bawdy ‘20s to perfection with her large and colorful cast of characters… Art and the creative process are at the heart of Gynther’s novel, along with portraits of people we wish to know and a story for readers to devour.”

Descriere

Set in 1920s Paris, New York socialite and model Lee Miller, catches the eye of Man Ray, one of the twentieth century's defining photographers.