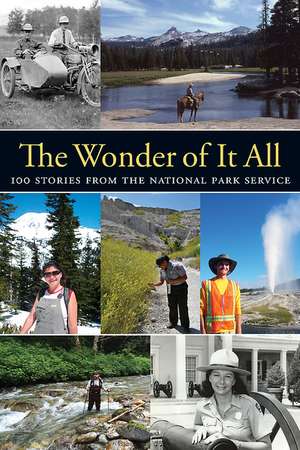

The Wonder of It All: 100 Stories from the National Park Service

Editat de Yosemite Conservancyen Limba Engleză Paperback – 14 mar 2016

Since the founding of the National Park Service in 1916, tens of thousands of NPS employees and volunteers have devoted themselves to preserving our public lands, which today number more than 400. Each person’s NPS career is unique, seasoned with daily duties, grand adventures, and everything in between! Yet there is one common element: each person has plenty of material for terrific stories about living and working in America’s most special places.

These 100 true stories from current and past NPS employees and volunteers make for an engrossing, funny, and often moving read, with something for everyone. The writers welcome visitors, ride the rails, collar caribou, reenact and make history, and every day face the mystery of wildness—including plenty of bears!—all for America’s public lands.

Featuring more than 100 photographs and stories from 80 different parks, monuments, and historic sites, stretching from the coast of Maine to American Samoa, The Wonder of It All is sure to inspire a new generation to cherish the natural and cultural resources that the National Park Service was born to preserve.

These 100 true stories from current and past NPS employees and volunteers make for an engrossing, funny, and often moving read, with something for everyone. The writers welcome visitors, ride the rails, collar caribou, reenact and make history, and every day face the mystery of wildness—including plenty of bears!—all for America’s public lands.

Featuring more than 100 photographs and stories from 80 different parks, monuments, and historic sites, stretching from the coast of Maine to American Samoa, The Wonder of It All is sure to inspire a new generation to cherish the natural and cultural resources that the National Park Service was born to preserve.

Preț: 78.00 lei

Preț vechi: 97.22 lei

-20% Nou

Puncte Express: 117

Preț estimativ în valută:

14.92€ • 15.62$ • 12.35£

14.92€ • 15.62$ • 12.35£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781930238626

ISBN-10: 1930238622

Pagini: 320

Ilustrații: B&W photos

Dimensiuni: 152 x 226 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.48 kg

Editura: Yosemite Conservancy

ISBN-10: 1930238622

Pagini: 320

Ilustrații: B&W photos

Dimensiuni: 152 x 226 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.48 kg

Editura: Yosemite Conservancy

Cuprins

Preface by Jon Jarvis

Foreword by Dayton Duncan

Acknowledgments

1. Getting Started

2. Life-Changing Moments

3. People to Remember

4. Stories from the Field

5. Volunteer Adventures

6. Love of Place

7. Looking Back, Moving Forward

Index of Featured National Park Service Units

Index of Authors and Titles

Quotation Sources

Photograph Credits

Foreword by Dayton Duncan

Acknowledgments

1. Getting Started

2. Life-Changing Moments

3. People to Remember

4. Stories from the Field

5. Volunteer Adventures

6. Love of Place

7. Looking Back, Moving Forward

Index of Featured National Park Service Units

Index of Authors and Titles

Quotation Sources

Photograph Credits

Recenzii

LIBRARY JOURNAL (January 5, 2016):

"Each story is imbued with the authors’ passion for their work and relates insider details that will be of interest to past and future visitors. . . . A fun choice for careers shelves and a great browse for parks enthusiasts."

NATIONAL PARKS TRAVELER (January 20, 2016):

"As we celebrate the National Park Service's centennial in 2016, here's a great read. . . . [Within] this book's covers you'll find descriptions of the singular moments, grand adventures, and careers, that can inspire an outdoor life. You'll want to read, and reread these stories, and perhaps one will touch you enough to volunteer, or make this your own career as the National Park Service embarks on the next 100 years."

Notă biografică

Yosemite Conservancy's publications inspire people to preserve and protect Yosemite National Park’s resources and enrich the visitor’s experience.

Extras

Preface by Jon Jarvis, director, National Park Service

Standing before many large, tattooed Hawaiian men bearing sharktoothed war clubs, feeling rather vulnerable in the lavalava I was wearing (which is little more than a six-foot-long wedgie), I had the honor of being chanted into the circle for the annual ’ava (kava) ceremony at Pu’ukohola Heiau National Historic Site on the big island of Hawai’i. This is the place where King Kamehameha united the islands for the first time, and it is still the center for passionate discussions of Native Hawaiian sovereignty. After hours of singing, chanting, dances, and many coconut-shell cups of the mouth-numbing kava elixir, I was asked to speak before the traditionally dressed group. I said I was both honored and humbled by the responsibility to care for these sacred places, which are not only important for their history but also for their inspirational and cultural value. I said we of the National Park Service are the stewards of the place, but it is our partnership with Native Hawaiians that keeps the stories alive over the centuries. I said we commit to carrying this place and its story into perpetuity. At the end of the ceremony, a man came to me and thanked me; and to seal the deal in the Hawaiian way, we touched foreheads and shared our breath.

National Park Service employees and our many park friends are, at our core, storytellers through place. I have said many times that we must speak for three entities that have no voice: the people of the past, the children of the future, and nature itself. They deserve to be heard, for our actions affect how the past will be remembered, what the future generations will inherit, and how our planet will be treated. Our most powerful tool is story, told with passion and intelligence on the ground where the story emerged. We shoulder the task of understanding these stories from a scientific and scholarly foundation, and must present them, without bias, to a listening public, hoping they will go home with a better understanding and a deeper passion for the past, future, and our environment.

Like my colleagues in the National Park Service and the contributors to this book, we gather our own stories from moving experiences. It can be an encounter with a visitor, especially a child, whose curiosity and wonder are ignited by our skill at showing them the natural world. It can be the act of standing in a place of history, on the bloody fields of the Civil War, or at Thomas Jefferson’s desk, feeling the chill of being in the spot that shaped our country’s independence. It can be the edge of an arroyo, with the canyon wren trilling as the sun settles into the desert. It can be a mountain forest, where the only sound is the soft shush of falling snowflakes. These moments accumulate in us, they give us strength—they reinforce our resolve that these parks need us. And when we share these stories, they build our nation’s commitment to the preservation of our national parks for the enjoyment of future generations.

This book is dedicated to inspiring stories from inspiring places&mdashfrom the past, and for the next one hundred years and beyond. We invite you to find your park and create your own stories.

________________________________________________________

From the Foreword by Dayton Duncan, filmmaker and author

The real power behind the national park idea is always personal. It is something you feel. It is an experience you never forget. As part of the National Park Service’s centennial, when it invites all Americans to “Find Your Park,” it is also launching an ambitious program to get every fourth grade student in the nation to some park, hoping that the youngsters we expose to any park today will become tomorrow’s guardians of “America’s best idea.” We can’t predict what their encounter will do for them. But I think we all know they will be better for it. I know this from personal experience; and since this is a book of stories, I will add my own.

In 1959, when I was a fourth grader in a little town in Iowa, I had my first encounter with national parks. Both of my parents worked—an unusual thing in those days—and until then, what vacations they had were more likely spent repainting our house or staying close to home. We couldn’t afford long trips. But that summer, we borrowed my grandmother’s car and some friends’ camping equipment and headed west, because my mother wanted to broaden my sister’s and my horizons. In preparation, she assigned me to look over maps and tourist brochures from the states we would visit to help plan where we would go. She said that national parks would be a major part of our trip: they were important, she believed, but they were also places we could afford. …

That trip was the greatest adventure of my young life, still vivid in my memory and my imagination as all those new vistas opened up for me. I can’t say that I returned home already knowing that I would end up spending most of my adult life traveling the backroads of this great country, getting to know its varied landscapes and the history that has unfolded in our nation’s own journey across it. But that is what I have ended up doing. Looking back, I think the seed for it was surely planted by my mother when she gave me those maps and those brochures; encouraged me, as a fourth grader, to study them; and then took me to see those places in person. …

And so, forty years later, after I had become a parent, I took my family on a similar trip. I got to watch as my children saw their first geyser, their first moose, their first bears at Yellowstone. …

My daughter shares the same name as my mother, Caroline Emily Duncan, and as I held her little hand as a father, I could also feel the touch of my mother’s hand as a son, nearly half a century earlier. I could feel the passing of generations pulsing through our hands, the past and the present united in that transcendent moment in the presence of something bigger than any of us.

In my imagination, I could sense the future as well. I could imagine—I could feel—my daughter holding the small hand of one of her children some day at that same, still unchanged place, feeling the same thing. And I thought, this is as close to an encounter with eternity as I will ever get in this life.

_________________________________________________________

Story from Chapter 1, "Getting Started":

Rangers Don’t Eat White Bread

by Jim Milestone

It was the summer of 1973; I was a park aid working in the Yosemite Museum. I had been hired as a taxidermist to stuff birds hit by cars and shuttle buses, for study specimens and exhibits.

Shortly after my arrival, however, it was discovered that I knew more about Yosemite than most visitors. So, beyond my duties as the valley’s resident taxidermist, my supervisor chose to put me at the front desk of the visitor center to provide basic information to the multitudes of park visitors. (The visitor center staff was being slammed with millions of visitors, and rather than have one of their talented park interpreters taking up their time explaining where the bathroom was located or how to drive to Glacier Point, they thought this young nineteen-year-old college student from San Francisco could do the job just fine.) This assignment required a park-ranger uniform, so I was driven down to Merced, California, to visit the Alford and Ferguson Uniform Store.

I was proud to wear the National Park Service uniform and especially enjoyed wearing the ranger hat. One day in the visitor center, with nearly a hundred people surrounding the information desk, I pointed my left arm to a bookshelf across the room. As my eyes followed my extended arm, I caught site of the National Park Service arrowhead patch sewn onto the shoulder of my gray, short-sleeve shirt. It gave me pause that I was wearing this historic and iconic arrowhead. I was part of a mission associated with a great agency that managed these spectacular lands—the finest landscapes of America.

One evening after work, I headed back to my tent cabin in Camp 6 and stopped at the ever-crowded grocery store in Yosemite Valley. It was August, and I had been working in Yosemite Valley for over two months. Being a park aid meant minimum pay, and I had a very meager diet. My menu consisted of peanut-butter sandwiches and chicken pot pies.

Having just come from work, I was still wearing my ranger uniform. As I reached up to pull a bag of Wonder Bread off the shelf, a large man’s hand grasped my thin wrist. I heard him say from behind me in a deep, controlled voice, “Ranger’s don’t eat white bread!”

Turning around, expecting to see a park-staff friend, I was surprised to see a tall, bearded fellow who appeared to have just come out of the park’s wilderness. Still holding onto my extended wrist, he directed my arm to the whole-wheat bread section and released it.

“Ranger’s don’t eat white bread!” he repeated. And with that, he walked away to the cash-register line.

I looked at the loaf of whole-wheat bread in my hand and realized that I could eat this. I collected my Concord jam and peanut butter, and headed to the registers, seeking this man out.

Catching up to him, I was laughing to myself at what had just happened.

“So where are you from?” I asked him.

He told me he was from downtown Los Angeles. He said he was a computer programmer in a skyscraper overlooking the city, and his dream job would be that of a park ranger. He saved up all of his vacation time so he could go backpacking in Yosemite every summer. He told me that he would love to have my job in Yosemite; and his image of park rangers involves people who take care of themselves, are in great physical shape, and eat wholesome and healthy food.

On another day, a young maintenance woman came into the Happy Isles Visitor Center and pleaded with me to scare off a black bear that had climbed into her large garbage dumpster. I shut down the center and walked outside to the dumpster. Thirty to forty visitors were standing around it with their Kodak Brownie cameras, taking photos of the bear on top of the large open garbage box. I really didn’t know what to do! But I was wearing a National Park Service ranger uniform, flat hat, and gold badge. So I stood akimbo, with my hands on my waist; and in the deepest voices I could muster, I said loudly, “Bear, get down from there!” The bear heard my voice; looked over his shoulder at me, the ranger; and fled immediately off the dumpster like his life depended on it. The visitors turned to me in awe.

“The Ranger has spoken,” I thought to myself. “This is the coolest thing I have done all summer!” And I turned and walked stoically back to the visitor center without saying another word.

The summer of 1973 left a strong impression on me as to how the public views the perception of the National Park Service ranger. Rangers are composed of an elite group of men and women who have many responsibilities and duties, one of which is upholding the traditions and image of the National Park Service ranger. It is wrapped in the fleeting myth of the Wild West and is as important as any iconic landscape or cultural monument found within the National Park Service’s system. The image of the national park ranger is one of high standards and integrity that we must live by every day as we wear the National Park Service uniform.

Since the summer of 1973, I only eat whole-wheat bread.

_______________________________________________________

Story from "Stories From the Field":

A Good Old-Fashioned Mountain Rescue

by Jane Marie Allen Farmer

In the 1980s, cell phones were nonexistent, which meant rescue could be a long way off. But I was a fresh seasonal “interp” with a new EMT certification and about to use my training.

High atop the Great Smoky Mountains at Peck’s Corner trail shelter, a hiker’s wilderness vacation had abruptly turned lethal. He had a spontaneous pneumothorax—a blown-out lung, and he could be dead by morning.

His friend, unfamiliar with the trails, headed the long way for help. Ten miles later, he hailed a visitor in a car, who drove to relay the critical information. It was sunset when rangers finally got the report.

Foggy weather and tall forest prohibited a helicopter; Peck’s Corner was accessible only by foot or horseback. A horseback rescue team was abysmal but the best alternative. A law-enforcement (LE) ranger quickly set off on foot to triage as the rest of us prepared for the rescue.

We trailered the horses and equipment three-and-a-half miles on a rugged dirt road. As we tacked up in the illumination of the pickup truck’s auxiliary lights, I noticed one saddle had no stirrups. A return to the barn would take another precious hour. It was my mistake, so I would ride the stirrupless saddle six miles up the mountain. The night was destined to be tough.

As we mounted, the triage LE ranger radioed that he had arrived at the trail shelter. He confirmed the injured hiker was in bad shape. With more than six hours since the rescue hiker had left his injured friend, the golden hour of rescue success was well behind us.

Horses like routine. We had surprised them with emergency night duty, so I worried they would be fractious and resentful. Saddle packs were loaded with bulky, heavy oxygen cylinders, and bulged with blankets and medical equipment. Our trail was rough and slinked narrowly up the steep and foggy mountain.

The lead EMT rode Charlie Brown, the most energetic horse. Charlie’s quirks included a strong fear of wild hogs. Unfortunately, wild European hogs were common on this trail. They are most active at night and can sometimes be quite aggressive. I hoped we would not see any that night.

Hauling up the mountain, I had plenty of time to review spontaneous pneumothorax in my head. I wondered how long a person could survive while their ruptured lung gradually filled their chest cavity with air. It seems ironic that the act of breathing could eventually crush the heart and kill a person.

The image of us throwing a corpse over a saddle and tying it to the horse cowboy-style kept floating in and out of my mind. I wondered if the other rangers knew how to secure a corpse to a horse. It was nothing I had learned in EMT training.

The horses delivered us to the shelter in a little under two hours. The man was still alive but in a lot of pain. Via radio, Medical Command ordered us to bring him down immediately—easy for them to say, sitting in their sterile, well-equipped hospital.

Another hour passed as we rearranged our equipment and hoisted the injured man onto Charlie Brown. The guttural groans the hiker emitted as we shoved him up into the saddle made me cringe. This was no way to treat a patient.

Wilderness rescues severely warp many rescue guidelines. Taking a man with a ruptured lung on a horse ride is insane, but it was our only alternative. With an oxygen tank strapped to his saddle, he was destined for the ride for his life.

I led Charlie Brown and his rider back down the mountain. The procession moved slowly. The fog completely darkened the already dangerous mountain trail. Charlie was sure-footed, but the trail seemed to have morphed into a mass of roots, rocks, and holes. Our headlamps dimmed.

I hoped Charlie’s night vision was better than mine, but I guessed he was depending on me to be his eyes. I carefully picked the way down the trail. Every time Charlie took a rough step, the man swayed dangerously and groaned painfully.

Two-thirds down the mountain, Charlie’s head shot up. He stopped abruptly, his eyes widened and ears pricked—the classic symptoms of a frightened horse ready to bolt.

I gently encouraged Charlie to move forward. He tentatively took two steps forward then three quickly back. The whiplash effect elicited a near scream from the patient. What was the matter with this horse? Did he sense something?

Then we all heard it, first on the right and then on the left. The underbrush was rustling all around us. Even in the dark fog, I could see the whites of Charlie’s eyes. We were surrounded by hogs, Charlie’s mortal enemies.

Fearing Charlie would throw his injured passenger, I desperately tried to reassure the horse, as a frightened horse can react violently. If a hog darted across the trail, I could lose control of this animal, ten times my size.

The lead EMT shouted to get out of there. I tugged gently on the reins. Charlie had trusted me this far, and I hoped he would trust me to get him past the hogs.

With little more than a stiffening of his gait, we quickly passed the porcine-infested area. The patient groaned at the pace, but he hung on gamely.

We arrived at the trailhead at 1:30 in the morning, happy to see the lights of a waiting ambulance.

Contrary to my worries, the horses had been great. They performed well without understanding why they were required to take part in the strange nighttime duty. Their ultimate reward was returning to the comfort of their pasture.

My ultimate reward came about a month after the incident in the form of a crudely drawn crayon picture of a brown horse with a black mane and tail. In a child’s block-style letters, it was captioned, “Charlie Brown.” The handwritten note that accompanied it said, “Thank you for saving my daddy’s life.”

It was one of my best ranger days.

Standing before many large, tattooed Hawaiian men bearing sharktoothed war clubs, feeling rather vulnerable in the lavalava I was wearing (which is little more than a six-foot-long wedgie), I had the honor of being chanted into the circle for the annual ’ava (kava) ceremony at Pu’ukohola Heiau National Historic Site on the big island of Hawai’i. This is the place where King Kamehameha united the islands for the first time, and it is still the center for passionate discussions of Native Hawaiian sovereignty. After hours of singing, chanting, dances, and many coconut-shell cups of the mouth-numbing kava elixir, I was asked to speak before the traditionally dressed group. I said I was both honored and humbled by the responsibility to care for these sacred places, which are not only important for their history but also for their inspirational and cultural value. I said we of the National Park Service are the stewards of the place, but it is our partnership with Native Hawaiians that keeps the stories alive over the centuries. I said we commit to carrying this place and its story into perpetuity. At the end of the ceremony, a man came to me and thanked me; and to seal the deal in the Hawaiian way, we touched foreheads and shared our breath.

National Park Service employees and our many park friends are, at our core, storytellers through place. I have said many times that we must speak for three entities that have no voice: the people of the past, the children of the future, and nature itself. They deserve to be heard, for our actions affect how the past will be remembered, what the future generations will inherit, and how our planet will be treated. Our most powerful tool is story, told with passion and intelligence on the ground where the story emerged. We shoulder the task of understanding these stories from a scientific and scholarly foundation, and must present them, without bias, to a listening public, hoping they will go home with a better understanding and a deeper passion for the past, future, and our environment.

Like my colleagues in the National Park Service and the contributors to this book, we gather our own stories from moving experiences. It can be an encounter with a visitor, especially a child, whose curiosity and wonder are ignited by our skill at showing them the natural world. It can be the act of standing in a place of history, on the bloody fields of the Civil War, or at Thomas Jefferson’s desk, feeling the chill of being in the spot that shaped our country’s independence. It can be the edge of an arroyo, with the canyon wren trilling as the sun settles into the desert. It can be a mountain forest, where the only sound is the soft shush of falling snowflakes. These moments accumulate in us, they give us strength—they reinforce our resolve that these parks need us. And when we share these stories, they build our nation’s commitment to the preservation of our national parks for the enjoyment of future generations.

This book is dedicated to inspiring stories from inspiring places&mdashfrom the past, and for the next one hundred years and beyond. We invite you to find your park and create your own stories.

________________________________________________________

From the Foreword by Dayton Duncan, filmmaker and author

The real power behind the national park idea is always personal. It is something you feel. It is an experience you never forget. As part of the National Park Service’s centennial, when it invites all Americans to “Find Your Park,” it is also launching an ambitious program to get every fourth grade student in the nation to some park, hoping that the youngsters we expose to any park today will become tomorrow’s guardians of “America’s best idea.” We can’t predict what their encounter will do for them. But I think we all know they will be better for it. I know this from personal experience; and since this is a book of stories, I will add my own.

In 1959, when I was a fourth grader in a little town in Iowa, I had my first encounter with national parks. Both of my parents worked—an unusual thing in those days—and until then, what vacations they had were more likely spent repainting our house or staying close to home. We couldn’t afford long trips. But that summer, we borrowed my grandmother’s car and some friends’ camping equipment and headed west, because my mother wanted to broaden my sister’s and my horizons. In preparation, she assigned me to look over maps and tourist brochures from the states we would visit to help plan where we would go. She said that national parks would be a major part of our trip: they were important, she believed, but they were also places we could afford. …

That trip was the greatest adventure of my young life, still vivid in my memory and my imagination as all those new vistas opened up for me. I can’t say that I returned home already knowing that I would end up spending most of my adult life traveling the backroads of this great country, getting to know its varied landscapes and the history that has unfolded in our nation’s own journey across it. But that is what I have ended up doing. Looking back, I think the seed for it was surely planted by my mother when she gave me those maps and those brochures; encouraged me, as a fourth grader, to study them; and then took me to see those places in person. …

And so, forty years later, after I had become a parent, I took my family on a similar trip. I got to watch as my children saw their first geyser, their first moose, their first bears at Yellowstone. …

My daughter shares the same name as my mother, Caroline Emily Duncan, and as I held her little hand as a father, I could also feel the touch of my mother’s hand as a son, nearly half a century earlier. I could feel the passing of generations pulsing through our hands, the past and the present united in that transcendent moment in the presence of something bigger than any of us.

In my imagination, I could sense the future as well. I could imagine—I could feel—my daughter holding the small hand of one of her children some day at that same, still unchanged place, feeling the same thing. And I thought, this is as close to an encounter with eternity as I will ever get in this life.

_________________________________________________________

Story from Chapter 1, "Getting Started":

Rangers Don’t Eat White Bread

by Jim Milestone

It was the summer of 1973; I was a park aid working in the Yosemite Museum. I had been hired as a taxidermist to stuff birds hit by cars and shuttle buses, for study specimens and exhibits.

Shortly after my arrival, however, it was discovered that I knew more about Yosemite than most visitors. So, beyond my duties as the valley’s resident taxidermist, my supervisor chose to put me at the front desk of the visitor center to provide basic information to the multitudes of park visitors. (The visitor center staff was being slammed with millions of visitors, and rather than have one of their talented park interpreters taking up their time explaining where the bathroom was located or how to drive to Glacier Point, they thought this young nineteen-year-old college student from San Francisco could do the job just fine.) This assignment required a park-ranger uniform, so I was driven down to Merced, California, to visit the Alford and Ferguson Uniform Store.

I was proud to wear the National Park Service uniform and especially enjoyed wearing the ranger hat. One day in the visitor center, with nearly a hundred people surrounding the information desk, I pointed my left arm to a bookshelf across the room. As my eyes followed my extended arm, I caught site of the National Park Service arrowhead patch sewn onto the shoulder of my gray, short-sleeve shirt. It gave me pause that I was wearing this historic and iconic arrowhead. I was part of a mission associated with a great agency that managed these spectacular lands—the finest landscapes of America.

One evening after work, I headed back to my tent cabin in Camp 6 and stopped at the ever-crowded grocery store in Yosemite Valley. It was August, and I had been working in Yosemite Valley for over two months. Being a park aid meant minimum pay, and I had a very meager diet. My menu consisted of peanut-butter sandwiches and chicken pot pies.

Having just come from work, I was still wearing my ranger uniform. As I reached up to pull a bag of Wonder Bread off the shelf, a large man’s hand grasped my thin wrist. I heard him say from behind me in a deep, controlled voice, “Ranger’s don’t eat white bread!”

Turning around, expecting to see a park-staff friend, I was surprised to see a tall, bearded fellow who appeared to have just come out of the park’s wilderness. Still holding onto my extended wrist, he directed my arm to the whole-wheat bread section and released it.

“Ranger’s don’t eat white bread!” he repeated. And with that, he walked away to the cash-register line.

I looked at the loaf of whole-wheat bread in my hand and realized that I could eat this. I collected my Concord jam and peanut butter, and headed to the registers, seeking this man out.

Catching up to him, I was laughing to myself at what had just happened.

“So where are you from?” I asked him.

He told me he was from downtown Los Angeles. He said he was a computer programmer in a skyscraper overlooking the city, and his dream job would be that of a park ranger. He saved up all of his vacation time so he could go backpacking in Yosemite every summer. He told me that he would love to have my job in Yosemite; and his image of park rangers involves people who take care of themselves, are in great physical shape, and eat wholesome and healthy food.

On another day, a young maintenance woman came into the Happy Isles Visitor Center and pleaded with me to scare off a black bear that had climbed into her large garbage dumpster. I shut down the center and walked outside to the dumpster. Thirty to forty visitors were standing around it with their Kodak Brownie cameras, taking photos of the bear on top of the large open garbage box. I really didn’t know what to do! But I was wearing a National Park Service ranger uniform, flat hat, and gold badge. So I stood akimbo, with my hands on my waist; and in the deepest voices I could muster, I said loudly, “Bear, get down from there!” The bear heard my voice; looked over his shoulder at me, the ranger; and fled immediately off the dumpster like his life depended on it. The visitors turned to me in awe.

“The Ranger has spoken,” I thought to myself. “This is the coolest thing I have done all summer!” And I turned and walked stoically back to the visitor center without saying another word.

The summer of 1973 left a strong impression on me as to how the public views the perception of the National Park Service ranger. Rangers are composed of an elite group of men and women who have many responsibilities and duties, one of which is upholding the traditions and image of the National Park Service ranger. It is wrapped in the fleeting myth of the Wild West and is as important as any iconic landscape or cultural monument found within the National Park Service’s system. The image of the national park ranger is one of high standards and integrity that we must live by every day as we wear the National Park Service uniform.

Since the summer of 1973, I only eat whole-wheat bread.

_______________________________________________________

Story from "Stories From the Field":

A Good Old-Fashioned Mountain Rescue

by Jane Marie Allen Farmer

In the 1980s, cell phones were nonexistent, which meant rescue could be a long way off. But I was a fresh seasonal “interp” with a new EMT certification and about to use my training.

High atop the Great Smoky Mountains at Peck’s Corner trail shelter, a hiker’s wilderness vacation had abruptly turned lethal. He had a spontaneous pneumothorax—a blown-out lung, and he could be dead by morning.

His friend, unfamiliar with the trails, headed the long way for help. Ten miles later, he hailed a visitor in a car, who drove to relay the critical information. It was sunset when rangers finally got the report.

Foggy weather and tall forest prohibited a helicopter; Peck’s Corner was accessible only by foot or horseback. A horseback rescue team was abysmal but the best alternative. A law-enforcement (LE) ranger quickly set off on foot to triage as the rest of us prepared for the rescue.

We trailered the horses and equipment three-and-a-half miles on a rugged dirt road. As we tacked up in the illumination of the pickup truck’s auxiliary lights, I noticed one saddle had no stirrups. A return to the barn would take another precious hour. It was my mistake, so I would ride the stirrupless saddle six miles up the mountain. The night was destined to be tough.

As we mounted, the triage LE ranger radioed that he had arrived at the trail shelter. He confirmed the injured hiker was in bad shape. With more than six hours since the rescue hiker had left his injured friend, the golden hour of rescue success was well behind us.

Horses like routine. We had surprised them with emergency night duty, so I worried they would be fractious and resentful. Saddle packs were loaded with bulky, heavy oxygen cylinders, and bulged with blankets and medical equipment. Our trail was rough and slinked narrowly up the steep and foggy mountain.

The lead EMT rode Charlie Brown, the most energetic horse. Charlie’s quirks included a strong fear of wild hogs. Unfortunately, wild European hogs were common on this trail. They are most active at night and can sometimes be quite aggressive. I hoped we would not see any that night.

Hauling up the mountain, I had plenty of time to review spontaneous pneumothorax in my head. I wondered how long a person could survive while their ruptured lung gradually filled their chest cavity with air. It seems ironic that the act of breathing could eventually crush the heart and kill a person.

The image of us throwing a corpse over a saddle and tying it to the horse cowboy-style kept floating in and out of my mind. I wondered if the other rangers knew how to secure a corpse to a horse. It was nothing I had learned in EMT training.

The horses delivered us to the shelter in a little under two hours. The man was still alive but in a lot of pain. Via radio, Medical Command ordered us to bring him down immediately—easy for them to say, sitting in their sterile, well-equipped hospital.

Another hour passed as we rearranged our equipment and hoisted the injured man onto Charlie Brown. The guttural groans the hiker emitted as we shoved him up into the saddle made me cringe. This was no way to treat a patient.

Wilderness rescues severely warp many rescue guidelines. Taking a man with a ruptured lung on a horse ride is insane, but it was our only alternative. With an oxygen tank strapped to his saddle, he was destined for the ride for his life.

I led Charlie Brown and his rider back down the mountain. The procession moved slowly. The fog completely darkened the already dangerous mountain trail. Charlie was sure-footed, but the trail seemed to have morphed into a mass of roots, rocks, and holes. Our headlamps dimmed.

I hoped Charlie’s night vision was better than mine, but I guessed he was depending on me to be his eyes. I carefully picked the way down the trail. Every time Charlie took a rough step, the man swayed dangerously and groaned painfully.

Two-thirds down the mountain, Charlie’s head shot up. He stopped abruptly, his eyes widened and ears pricked—the classic symptoms of a frightened horse ready to bolt.

I gently encouraged Charlie to move forward. He tentatively took two steps forward then three quickly back. The whiplash effect elicited a near scream from the patient. What was the matter with this horse? Did he sense something?

Then we all heard it, first on the right and then on the left. The underbrush was rustling all around us. Even in the dark fog, I could see the whites of Charlie’s eyes. We were surrounded by hogs, Charlie’s mortal enemies.

Fearing Charlie would throw his injured passenger, I desperately tried to reassure the horse, as a frightened horse can react violently. If a hog darted across the trail, I could lose control of this animal, ten times my size.

The lead EMT shouted to get out of there. I tugged gently on the reins. Charlie had trusted me this far, and I hoped he would trust me to get him past the hogs.

With little more than a stiffening of his gait, we quickly passed the porcine-infested area. The patient groaned at the pace, but he hung on gamely.

We arrived at the trailhead at 1:30 in the morning, happy to see the lights of a waiting ambulance.

Contrary to my worries, the horses had been great. They performed well without understanding why they were required to take part in the strange nighttime duty. Their ultimate reward was returning to the comfort of their pasture.

My ultimate reward came about a month after the incident in the form of a crudely drawn crayon picture of a brown horse with a black mane and tail. In a child’s block-style letters, it was captioned, “Charlie Brown.” The handwritten note that accompanied it said, “Thank you for saving my daddy’s life.”

It was one of my best ranger days.