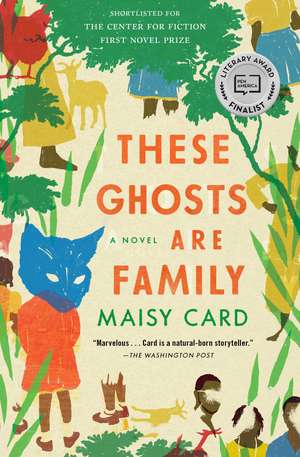

These Ghosts Are Family: A Novel

Autor Maisy Carden Limba Engleză Paperback – 14 apr 2021

A “rich, ambitious debut novel” (The New York Times Book Review) that reveals the ways in which a Jamaican family forms and fractures over generations, in the tradition of Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi.

*An Entertainment Weekly, Millions, and LitHub Most Anticipated Book of 2020 Pick and Buzz Magazine’s Top New Book of the New Decade*

Stanford Solomon’s shocking, thirty-year-old secret is about to change the lives of everyone around him. Stanford has done something no one could ever imagine. He is a man who faked his own death and stole the identity of his best friend. Stanford Solomon is actually Abel Paisley.

And now, nearing the end of his life, Stanford is about to meet his firstborn daughter, Irene Paisley, a home health aide who has unwittingly shown up for her first day of work to tend to the father she thought was dead.

These Ghosts Are Family revolves around the consequences of Abel’s decision and tells the story of the Paisley family from colonial Jamaica to present-day Harlem. There is Vera, whose widowhood forced her into the role of a single mother. There are two daughters and a granddaughter who have never known they are related. And there are others, like the houseboy who loved Vera, whose lives might have taken different courses if not for Abel Paisley’s actions.

This “rich and layered story” (Kirkus Reviews) explores the ways each character wrestles with their ghosts and struggles to forge independent identities outside of the family and their trauma. The result is a “beguiling…vividly drawn, and compelling” (BookPage, starred review) portrait of a family and individuals caught in the sweep of history, slavery, migration, and the more personal dramas of infidelity, lost love, and regret.

Preț: 90.95 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 136

Preț estimativ în valută:

17.41€ • 17.98$ • 14.49£

17.41€ • 17.98$ • 14.49£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 04-18 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781982117443

ISBN-10: 1982117443

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 133 x 203 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Colecția Simon & Schuster

ISBN-10: 1982117443

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 133 x 203 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Colecția Simon & Schuster

Notă biografică

Maisy Card holds an MFA in Fiction from Brooklyn College and is a public librarian. Her writing has appeared in Lenny Letter, School Library Journal, Agni, Sycamore Review, Liars’ League NYC, and Ampersand Review. Maisy was born in St. Catherine, Jamaica, but was raised in Queens, New York. Maisy earned an MLIS from Rutgers University and a BA in English and American Studies from Wesleyan University. She is the author of These Ghosts Are Family.

Extras

1. The True Death of Abel PaisleyTHE TRUE DEATH OF ABEL PAISLEY

Harlem, 2005

Let’s say that you are a sixty-nine-year-old Jamaican man called Stanford, or Stan for short, who once faked your own death. Though you have never used those words to describe what you did. At the time you’d thought of it as seizing an opportunity placed before you by God, but since your wife, Adele, died a month ago, you’ve convinced yourself her heart attack was retribution for your sin. So today you have gathered three of your female descendants in one house, even the daughter who has thought you dead all these years, and decided that you will finally tell them the truth: you are not who you say you are.

You have spent the last twenty years of your second life living in a brownstone in Harlem, running a West Indian grocery store. Recently, you shuttered the store. You have given up on fighting your arthritis pain and are finally sitting in the wheelchair Adele picked out. You are looking out of your parlor window, waiting for your daughter, the one who thinks you are dead, to arrive. It’s been thirty-five years since you’ve seen her, so you study each woman who passes your house for reflections of yourself. You haven’t bothered to shave, press your clothes, or comb your hair.

You are ready to be still and rot. You imagine the death of Stanford Solomon, unlike the abrupt end of Abel Paisley, will be achingly slow; already it feels like you are losing small pieces of yourself daily. To you, old age is the torture you deserve, a slow, insignificant death, your matter dispersing into the air like dandelion seeds until the day there’s nothing left.

When you died the first time, you were still a young man in your thirties and had been working in England for less than a year. It wasn’t easy for an immigrant, especially a black man, to find a decent job back then, but through a boy you’d known back in primary school, Stanford, you’d gotten a room and a job on a ship. You had no idea it was just the beginning of your streak of good luck.

You and Stanford were the chosen wogs they allowed to work alongside the white men. Stanford complained often about London. He hated the cold. He missed his grandmother and the tiny village, Harold Town, where you’d both grown up back in Jamaica. You’d already escaped the countryside for Kingston, and from there, London. You felt free. That sense of freedom and joy only dampened when you thought of the family you left behind. Your first wife, Vera, wrote you long letters weekly about how you’d abandoned her and left her to become a dried-up old spinster. But you both knew perfectly well that it was her idea for you to go to England, where she thought you’d somehow become a better provider. Your son, Vincent, was still in Vera’s womb when you sailed off. Your daughter, Irene, a stumbling toddler. You had barely settled in when Vera’s first letter arrived, with the list of things she wanted you to buy and send to them. With every letter the list grew longer, and you worried that you would never be enough.

The day you died, you were running along the dock because you were late for work while a container was being lowered onto the ship. You stopped short when the container fell, dropped from the crane, and thundered against the deck. You were close enough to hear the screaming.

“Who was it?” you heard someone shout.

“One of the wogs!” another answered. “It’s Abel!”

For a moment you were confused, hearing yourself pronounced dead. It was like one of those movies where the dead person’s spirit stands by watching as a crowd gathers around his body. But no, you were certain, it wasn’t your body, so you boarded the ship. The captain approached you immediately and said, “I’m sorry, mate. No way Abel could have survived that.”

You almost laugh now when you think of it—the one time racism worked in your favor. The captain had gotten his wogs confused, looked you right in the eye, and mistaken you for the other black guy. Abel was dead, crushed under the container. Unrecognizable. But you, Stanford now, could turn and go home.

Perhaps it’s telling about your nature that you did not hesitate. You nodded and turned and walked away, quickly, from Abel and all his responsibilities, before any of the others had a chance to recognize you. Back in your room at the boardinghouse, you riffled through your roommate’s things and learned what it really meant to be Stanford. You and Stanford actually did look alike, which made it a little easier to forgive the fact that all the white people had trouble telling you apart. You were the same height, the same light-brown complexion, the same lanky build. You, Abel, did not arrive dressed for an English winter, so you had even taken to wearing Stanford’s clothes.

Of course, you thought of your family. Your wife, Vera. You thought about the two life insurance policies you’d purchased. The one she’d made you take out before you left, and the one the company made mandatory. You decided that you were worth more to her dead. Vera was beautiful. She would find a new husband, a richer one; the children were young enough to embrace a new father, and they would finally live the life Vera thought that she deserved, the one she had no qualms about constantly demanding of you.

Stanford had little family. No wife. No children. That was what clinched things for you. Stanford was raised by his grandmother, who was in her seventies and losing her eyesight. You could continue writing her letters, sending her a little money, and there was no bother there. What surprised you was how right it felt. At least then.

When you met Adele shortly after you became Stanford, you connected with her immediately. Like you, she was Jamaican and had left her family to work in England, though at nineteen, she was almost fifteen years younger than you. You were as drawn to her as you had been to your first wife, and she to you. The difference was that Adele did not try to remake and mold you. When you told her the truth, the very first night you spent together, that you had taken your friend’s name, she did not try to dissuade you. Instead, she avoided the subject until you proposed, and she said yes on the condition that you live in America. As if leaving that country would leave the lie behind.

Later, the guilt would hit her first, a few years after coming to the U.S. She had started to go to church multiple times a week and suggested that you atone. You remember having laughed at the thought that getting down on your knees could redeem you. But since the day that she collapsed in the store, you’ve been thinking about your past. You’ve been thinking about that word, fake, and you decided you were right to never use it to describe what you’ve done. You are a thief, pure and simple. It wasn’t Stanford’s life you had stolen, for he would have lost that regardless. It was his death. Where is his soul now? Circling the world, looking for a grave that does not yet exist? Isn’t it about time you give him his due?

Your granddaughter has taught you to use the computer to kill some of your idle time. It was easier than you thought to find your first daughter, to track her journey from Jamaica to New York.

You are thinking of the grave that bears your real name and all of the people who needlessly mourned you when Irene finally arrives, the daughter who thinks you are dead. She is under the impression that she has been called to your house to care for an old man in a wheelchair. That old man is you. You didn’t realize just how little you’ve thought about her all these years until you watch her climb the stoop, and all the feeling you should have had for your firstborn suddenly rushes through you.

When she enters, you see her mother Vera’s wide, obstinate mouth, her large, slightly bulbous hazel eyes, her flaring nostrils. You can sense immediately, before she even speaks, that she also has her mother’s brutal tongue. You are intimidated. She has a look that says she is a frayed rope one tug away from snapping, and it occurs to you to wonder if, when you tell her the truth, she will kill you. In that moment, your death—your real death—flashes in your mind.

You have never had a premonition before, but now the certainty of it causes you to slump forward in your wheelchair. You have a vision of a woman supporting your weight as you make your way up the flight of stairs, bringing you all the way to the top, and then just letting you go, as if she’d just remembered she was supposed to be somewhere else.

Your daughter, who moments before had introduced herself as Irene, the name you gave her, bends down and asks, “You alright, Mr. Solomon?” You sit up straight, or as straight as an old man with scoliosis and arthritis can, and say, “You can call me Stanford.”

Now let’s say you are a thirty-seven-year-old home health aide named Irene whose father faked his own death, but you don’t know it yet. Today is the day he will tell you. All you know is that he died when you were very young. You have no memory of him whatsoever. You recognize his face only as a young man in photographs. Though your mother always told you your father was timid and spineless, in one photo you remember a square-jawed man with reddish hair, face lightly freckled, dressed in a police uniform, one hand on his gun, his eyes so astute and focused it felt like they were alive and could see into you. You don’t recognize that face when you meet the old man who is your new client, for his red hair is white, and as far as you know, aging after death is impossible.

You do think it’s strange that this man called the agency and asked for you by name. He claimed another client recommended you, which you find unlikely. You do your job, but you don’t make much effort to be nice. You’ve lived in America for seven years and the only reason you came here at all, the only reason you agreed to do this miserable job in the U.S., was to get away from your family. Your brother and your mother. It seems ironic that you spend your time caring for other people’s parents, when you couldn’t stand the thought of doing so for your own.

Your husband left you and went back to Jamaica after the first month in Miami, but you stayed because you have two children who you’d sworn to keep away from the cancer that raised you. Instead you moved to Brooklyn where you had a childhood friend to help you. But Vera, your mother, died just a year later. Sometimes you regret not waiting. You would at least have inherited her house if you’d stayed in Jamaica. Now you are living in a basement apartment with your two kids, working nine hours a day, six days a week, changing colostomy bags and spoon-feeding strangers to stay afloat.

You misunderstand the look the old man gives you when you introduce yourself. You worry that he’s another pervert, that he’ll sneak pinches when your back is turned or when you’re on your knees, bent over cleaning. It happens so often you’re not even surprised anymore. You are grateful that he’s in a wheelchair—at least he can’t sneak up on you—although it means you’ll probably have to help him to the toilet. You might have to pull down his pants for him, which can lead to all kinds of undesirable propositions.

You are scrutinizing his features, speculating what kind of man you have in front of you, when the image of your father, dressed in a tweed suit, too hot for the Caribbean, that he had specially made for his journey away from you, flashes in your mind, but you don’t know why. It is the only photo you have of the two of you. He is standing under a mango tree with you in his arms. That tree became your favorite growing up. That tree became your father. Whenever you sat under that tree, you asked for things, and even though you rarely got them, you still imagined he could hear you.

It’s always been clear to you that your father’s death was the dividing line between hell and heaven. Even if you do not remember much about those days or years before he left, you know you had seen your mother smile, you carry the physical memory of being picked up and held, you swear there was laughter. Before he died, you didn’t know what it meant to be mishandled, to be jerked, to be shoved, to be slapped, to be pinched or even choked by her. You know because you remember the first time Vera did each of these things to you. Each time, afterward, you sat under the mango tree and asked the man in the picture who you thought was dead and therefore held some supernatural power to please protect you. He never did. Today you will finally know why.

You have always wondered who you’d be, where you would be, if he’d never left, if he had lived. You don’t think you would have run away from home and down the aisle with the first man who stood in front of you. Later, after he reveals his true identity to you, if you were to “accidentally” let him fall down the stairs, knowing the life you’ve lived, a life he caused, would anyone blame you?

Never mind. Instead, you are a thirty-four-year-old heroin addict named Estelle Solomon whose father once faked his own death. He did it before he had you, but you don’t know it yet. Today is the day that he’ll tell you. Sometime in the late afternoon. For now, you are lying, unaware, on a daybed in the basement of your family’s Harlem brownstone, where you’ve lived for the last eight years, since a judge made your parents the legal guardians of your daughter. You had begged your father to let you and Caren move into the garden apartment, right above you, because it has windows. But he screamed, “Is what you need windows fah? Why, when you spend fi yuh whole life asleep?” Instead, they kept your daughter upstairs with them and left you to stay in the basement. Your father seems determined to keep you alive but just as eager to bury you.

You weren’t always such an embarrassment. You worked very hard to become one.

You have been an addict for many years now. But before your mother died, you were also an artist. You could still hustle. You were taking and selling pictures. Occasionally, someone would put your photos on display in a café or a small gallery. Every once in a while you sold something, made a little money, and even came home and gave it to your father, telling him to buy something nice for your daughter with the money your art made you. He would never take it. Worse, he would throw it down on the floor in front of you, so both he and your mother would have to watch you gather the scattered bills from all over the room.

“After me nuh know where that money come from. Me nuh wan’ know what someone like you have fi do to come by it.”

Someone like you. He stopped short of calling you a whore for the sake of your mother. But you could feel how badly he wanted to.

You have always sensed a lie behind your parents’ words, have always suspected that their Jamaica was a place that did not exist. You have always wondered why they never chose, in all these years, to return to that island so perfect. Instead it was always the right weapon to throw in your face, always the only answer to their problems, their main problem always being you.

When you were younger, you would scream back at them that if in Jamaica, the daughters were pure, saved themselves until marriage, stood by their mother’s side every day in the kitchen and watched them cook, brought their father his slippers when he got home from the store, went to church every Sunday, never refused to recite the Lord’s Prayer at the table before a meal, didn’t proclaim themselves agnostics, wanted to be wives instead of artists, always agreed to stack canned food on the shelves of their father’s store after school, didn’t stand under the streetlights at night talking to boys from the block, did their own laundry and their father’s too, did not jump between their parents and cuss their father out every time he raised his voice at their mother, did not promise to kill their father if he dared threaten—only threatened—to one day slap their mother in the face. If in Jamaica, daughters did not run away from home and return pregnant by a man twice their age, did not go out partying instead of staying home with their newborn child, did not walk down the street in skirts so short they barely covered their pum-pum, did not make their mother cry and waste away with worry, never did drugs and if they did, were never so weak that they would become addicted. If in Jamaica, daughters were churned out of factories without the slightest defect, why the fuck didn’t they just go back there and leave you alone?

When your father tells you his secret, that he is not really Stanford Solomon, and therefore you in turn cannot be Estelle Solomon, that your family does not even exist, you will have your answer. And it is perfect.

Say you are an eighteen-year-old college student named Caren who lives in a Harlem brownstone with your mother, who is a heroin addict, and your wheelchair-bound Jamaican grandfather who faked his own death, but you won’t know it for a few hours.

Every morning when you wake up, you remember that your grandmother Adele, the person you loved above everyone else in this world, is gone. She worked so hard to shield you from your mother. She loved you so deep it almost rendered your mother’s love supplementary—a bonus—so that the times when Estelle was lucid enough to pay attention to you felt like a holiday, a special occasion. Every child knows that holidays don’t last. By the time you were eight, you had stopped being disappointed.

You don’t begrudge your mother. You can see how hard she is trying. You know she hates living in your grandfather’s house, but in the month since your grandma died, she no longer vanishes for days at a time, returning with no explanation. For the first time in your life, with the exception of an hour a day when she sneaks outside to score, you know exactly where you’ll find her. Knowing should comfort you, but on the rare occasion when you go to the basement and stare at her, passed out on the daybed, you can’t help but wish it had been her who had a heart attack instead of your grandmother. You think, What a waste of a life. The same words you’d overhear your grandmother mumble when she talked about Estelle. You are ashamed of your thoughts. Most of the time Estelle invokes pity in you, and you conclude that’s worse than hatred, for a child to pity their mother.

Later, when your grandfather tells you that he was born Abel Paisley and not Stanford Solomon, you will understand why your grandmother was so disgusted by Estelle’s addiction. Other people are so desperate to make a better life that they are willing to steal one, while your mother is fine with throwing hers away. Perhaps, a life does not belong exclusively to one person, you learn. Look how easily it can be passed from one person to the next until every bit of it is put to good use. You will wonder if there is someone out there who would wear your life better.

But before that, you notice that from the moment you wake up, your grandpa is acting strange. You had been begging him to get a home health aide for the last year because caring for him was getting to be too much for your grandmother, and now it is too much for you. All of a sudden there is one sitting with him at the kitchen table. He is giddy as he says her name to you, Irene, and you wonder if it has been too long since he’s seen a woman he wasn’t related to.

You are about to smile at Irene when you notice that she doesn’t bother to smile at you, barely tilts her head in your direction, before she returns to reading your grandpa’s newspaper. If your grandmother were here, the two of you would go upstairs and talk about this woman. For a moment, you imagine all of the things you would say about her, until you remember that your grandmother is gone. Briefly you contemplate going down to the basement and telling your mother about Irene, but that would be as exciting as talking to a corpse.

Since your grandmother left you, you’ve found it hard to think about anything else besides getting away from this family. So much so, you’ve started sleeping with one of your professors at City College. It helps the fantasy of running away. The irony that you might be following in your mother’s footsteps doesn’t escape you. Your father had been a professor, but your mother had been a high school girl who’d just had a bunch of college friends. Your birth cost him his marriage and his reputation, and even though he was kind the handful of times you visited him, you know he resented you. You speak to him only on holidays now, even though he just lives in Queens. But still, you want him to be proud of you. You are actually going to get a degree one day. You are actually going to leave this house.

Sometimes you imagine a scenario in which your professor leaves his wife and four children and buys a condo for the two of you in downtown Brooklyn. You are not sure what you would say if he were actually to propose this to you. He hasn’t talked about leaving his wife, hasn’t said he loves you. You might think less of him if he did. Besides, you have no intention of trading your dysfunctional family for another, being the reluctant stepmother to four resentful white kids. In your family, you are known as the smart one for a reason.

Now let’s say that you are a dead woman, six years on the other side, whose husband let you believe he was dead. When you were alive, they called you Vera, but here there is no need for names. You did not know the truth about your husband until your own death, but the timing of the knowledge made it no less infuriating. You have analyzed all the years you spent mad with guilt, thinking you were the one who sent him to his grave.

Death is just one long therapy session. You have gone over every second of your life and divided them into the misery you caused and the misery others caused you. You have been waiting for six years for this motherfucker to die, and you know that the day has finally arrived.

You look at the elaborate theater that your former husband is producing and you laugh (or you imagine yourself laughing; you no longer have a mouth or a face). He has asked the women down to the brownstone’s parlor. He has your daughter—your daughter who he barely even knew—help him move from his wheelchair to his favorite rocking chair, which he thinks makes him appear wise. Clearly, none of the women want to be there. The three of them settle side by side on a crushed-velvet settee barely listening, unaware of their blood connection.

You are there in the room with them, waiting for Abel to gather up his nerve. You have decided to choose one person in his house to be the catalyst of his death, to be briefly possessed by you long enough to get the deed done, but the question of who has stumped you. Who will hurt him the most?

You look at your own daughter, Irene, think she’s owed the revenge, but you can see both the past and the future and know that giving her guilt to carry is not doing her any favors. There is a cruel impulse inside her, one that you gave her, that you do not want to feed. You know that most of her misery was brought about by you. When she dies, you will face your own reckoning, but for now you have no plans to ruin her life any further.

You look at the other two women, his daughter and granddaughter, the products of the weak woman he married after you. You have passed her in the other place, for she’s dead now too. You thought you’d have harsh words for her, that her day of reckoning would come, but you mostly feel sorry for her. You can feel her pining for Abel, pleading with you to spare him, until you’ve recently had no choice but to shut her out.

You are so close to Abel as he tells them you can smell the Wray & Nephew rum on his breath, but he can’t see or sense you. When he says the words I was born Abel Paisley, you see your daughter shake her head. It will take her a while to understand that her father was alive all those years and left her behind to suffer with you. After he says the words I was born Abel Paisley, his daughter Estelle exhales deeply, tears form in her eyes, but then she just bursts out laughing. For the first time in her life, she actually looks at her father with gratitude. She actually turns to the old man and says, “Thank you.” Estelle puts her arms around her daughter, Caren, who, after he tells them, begins to cry.

Irene stands up and crosses the room, kneeling before Abel, and for a moment you worry that she will choke the life out of him before you even have a chance to. Instead she studies his face. She is thinking about the picture, the one under the mango tree, and when she recognizes him, she walks out of the room, collects her purse from the hall, and leaves for good, slamming the front door so hard it shakes you. You look at the two girls left in the room and reassure yourself that no matter which one ends him, it will actually be you. If only he could see you as he’s falling. If you still had a mouth, you would be laughing. If you still had a body, you would dance.

Harlem, 2005

Let’s say that you are a sixty-nine-year-old Jamaican man called Stanford, or Stan for short, who once faked your own death. Though you have never used those words to describe what you did. At the time you’d thought of it as seizing an opportunity placed before you by God, but since your wife, Adele, died a month ago, you’ve convinced yourself her heart attack was retribution for your sin. So today you have gathered three of your female descendants in one house, even the daughter who has thought you dead all these years, and decided that you will finally tell them the truth: you are not who you say you are.

You have spent the last twenty years of your second life living in a brownstone in Harlem, running a West Indian grocery store. Recently, you shuttered the store. You have given up on fighting your arthritis pain and are finally sitting in the wheelchair Adele picked out. You are looking out of your parlor window, waiting for your daughter, the one who thinks you are dead, to arrive. It’s been thirty-five years since you’ve seen her, so you study each woman who passes your house for reflections of yourself. You haven’t bothered to shave, press your clothes, or comb your hair.

You are ready to be still and rot. You imagine the death of Stanford Solomon, unlike the abrupt end of Abel Paisley, will be achingly slow; already it feels like you are losing small pieces of yourself daily. To you, old age is the torture you deserve, a slow, insignificant death, your matter dispersing into the air like dandelion seeds until the day there’s nothing left.

When you died the first time, you were still a young man in your thirties and had been working in England for less than a year. It wasn’t easy for an immigrant, especially a black man, to find a decent job back then, but through a boy you’d known back in primary school, Stanford, you’d gotten a room and a job on a ship. You had no idea it was just the beginning of your streak of good luck.

You and Stanford were the chosen wogs they allowed to work alongside the white men. Stanford complained often about London. He hated the cold. He missed his grandmother and the tiny village, Harold Town, where you’d both grown up back in Jamaica. You’d already escaped the countryside for Kingston, and from there, London. You felt free. That sense of freedom and joy only dampened when you thought of the family you left behind. Your first wife, Vera, wrote you long letters weekly about how you’d abandoned her and left her to become a dried-up old spinster. But you both knew perfectly well that it was her idea for you to go to England, where she thought you’d somehow become a better provider. Your son, Vincent, was still in Vera’s womb when you sailed off. Your daughter, Irene, a stumbling toddler. You had barely settled in when Vera’s first letter arrived, with the list of things she wanted you to buy and send to them. With every letter the list grew longer, and you worried that you would never be enough.

The day you died, you were running along the dock because you were late for work while a container was being lowered onto the ship. You stopped short when the container fell, dropped from the crane, and thundered against the deck. You were close enough to hear the screaming.

“Who was it?” you heard someone shout.

“One of the wogs!” another answered. “It’s Abel!”

For a moment you were confused, hearing yourself pronounced dead. It was like one of those movies where the dead person’s spirit stands by watching as a crowd gathers around his body. But no, you were certain, it wasn’t your body, so you boarded the ship. The captain approached you immediately and said, “I’m sorry, mate. No way Abel could have survived that.”

You almost laugh now when you think of it—the one time racism worked in your favor. The captain had gotten his wogs confused, looked you right in the eye, and mistaken you for the other black guy. Abel was dead, crushed under the container. Unrecognizable. But you, Stanford now, could turn and go home.

Perhaps it’s telling about your nature that you did not hesitate. You nodded and turned and walked away, quickly, from Abel and all his responsibilities, before any of the others had a chance to recognize you. Back in your room at the boardinghouse, you riffled through your roommate’s things and learned what it really meant to be Stanford. You and Stanford actually did look alike, which made it a little easier to forgive the fact that all the white people had trouble telling you apart. You were the same height, the same light-brown complexion, the same lanky build. You, Abel, did not arrive dressed for an English winter, so you had even taken to wearing Stanford’s clothes.

Of course, you thought of your family. Your wife, Vera. You thought about the two life insurance policies you’d purchased. The one she’d made you take out before you left, and the one the company made mandatory. You decided that you were worth more to her dead. Vera was beautiful. She would find a new husband, a richer one; the children were young enough to embrace a new father, and they would finally live the life Vera thought that she deserved, the one she had no qualms about constantly demanding of you.

Stanford had little family. No wife. No children. That was what clinched things for you. Stanford was raised by his grandmother, who was in her seventies and losing her eyesight. You could continue writing her letters, sending her a little money, and there was no bother there. What surprised you was how right it felt. At least then.

When you met Adele shortly after you became Stanford, you connected with her immediately. Like you, she was Jamaican and had left her family to work in England, though at nineteen, she was almost fifteen years younger than you. You were as drawn to her as you had been to your first wife, and she to you. The difference was that Adele did not try to remake and mold you. When you told her the truth, the very first night you spent together, that you had taken your friend’s name, she did not try to dissuade you. Instead, she avoided the subject until you proposed, and she said yes on the condition that you live in America. As if leaving that country would leave the lie behind.

Later, the guilt would hit her first, a few years after coming to the U.S. She had started to go to church multiple times a week and suggested that you atone. You remember having laughed at the thought that getting down on your knees could redeem you. But since the day that she collapsed in the store, you’ve been thinking about your past. You’ve been thinking about that word, fake, and you decided you were right to never use it to describe what you’ve done. You are a thief, pure and simple. It wasn’t Stanford’s life you had stolen, for he would have lost that regardless. It was his death. Where is his soul now? Circling the world, looking for a grave that does not yet exist? Isn’t it about time you give him his due?

Your granddaughter has taught you to use the computer to kill some of your idle time. It was easier than you thought to find your first daughter, to track her journey from Jamaica to New York.

You are thinking of the grave that bears your real name and all of the people who needlessly mourned you when Irene finally arrives, the daughter who thinks you are dead. She is under the impression that she has been called to your house to care for an old man in a wheelchair. That old man is you. You didn’t realize just how little you’ve thought about her all these years until you watch her climb the stoop, and all the feeling you should have had for your firstborn suddenly rushes through you.

When she enters, you see her mother Vera’s wide, obstinate mouth, her large, slightly bulbous hazel eyes, her flaring nostrils. You can sense immediately, before she even speaks, that she also has her mother’s brutal tongue. You are intimidated. She has a look that says she is a frayed rope one tug away from snapping, and it occurs to you to wonder if, when you tell her the truth, she will kill you. In that moment, your death—your real death—flashes in your mind.

You have never had a premonition before, but now the certainty of it causes you to slump forward in your wheelchair. You have a vision of a woman supporting your weight as you make your way up the flight of stairs, bringing you all the way to the top, and then just letting you go, as if she’d just remembered she was supposed to be somewhere else.

Your daughter, who moments before had introduced herself as Irene, the name you gave her, bends down and asks, “You alright, Mr. Solomon?” You sit up straight, or as straight as an old man with scoliosis and arthritis can, and say, “You can call me Stanford.”

Now let’s say you are a thirty-seven-year-old home health aide named Irene whose father faked his own death, but you don’t know it yet. Today is the day he will tell you. All you know is that he died when you were very young. You have no memory of him whatsoever. You recognize his face only as a young man in photographs. Though your mother always told you your father was timid and spineless, in one photo you remember a square-jawed man with reddish hair, face lightly freckled, dressed in a police uniform, one hand on his gun, his eyes so astute and focused it felt like they were alive and could see into you. You don’t recognize that face when you meet the old man who is your new client, for his red hair is white, and as far as you know, aging after death is impossible.

You do think it’s strange that this man called the agency and asked for you by name. He claimed another client recommended you, which you find unlikely. You do your job, but you don’t make much effort to be nice. You’ve lived in America for seven years and the only reason you came here at all, the only reason you agreed to do this miserable job in the U.S., was to get away from your family. Your brother and your mother. It seems ironic that you spend your time caring for other people’s parents, when you couldn’t stand the thought of doing so for your own.

Your husband left you and went back to Jamaica after the first month in Miami, but you stayed because you have two children who you’d sworn to keep away from the cancer that raised you. Instead you moved to Brooklyn where you had a childhood friend to help you. But Vera, your mother, died just a year later. Sometimes you regret not waiting. You would at least have inherited her house if you’d stayed in Jamaica. Now you are living in a basement apartment with your two kids, working nine hours a day, six days a week, changing colostomy bags and spoon-feeding strangers to stay afloat.

You misunderstand the look the old man gives you when you introduce yourself. You worry that he’s another pervert, that he’ll sneak pinches when your back is turned or when you’re on your knees, bent over cleaning. It happens so often you’re not even surprised anymore. You are grateful that he’s in a wheelchair—at least he can’t sneak up on you—although it means you’ll probably have to help him to the toilet. You might have to pull down his pants for him, which can lead to all kinds of undesirable propositions.

You are scrutinizing his features, speculating what kind of man you have in front of you, when the image of your father, dressed in a tweed suit, too hot for the Caribbean, that he had specially made for his journey away from you, flashes in your mind, but you don’t know why. It is the only photo you have of the two of you. He is standing under a mango tree with you in his arms. That tree became your favorite growing up. That tree became your father. Whenever you sat under that tree, you asked for things, and even though you rarely got them, you still imagined he could hear you.

It’s always been clear to you that your father’s death was the dividing line between hell and heaven. Even if you do not remember much about those days or years before he left, you know you had seen your mother smile, you carry the physical memory of being picked up and held, you swear there was laughter. Before he died, you didn’t know what it meant to be mishandled, to be jerked, to be shoved, to be slapped, to be pinched or even choked by her. You know because you remember the first time Vera did each of these things to you. Each time, afterward, you sat under the mango tree and asked the man in the picture who you thought was dead and therefore held some supernatural power to please protect you. He never did. Today you will finally know why.

You have always wondered who you’d be, where you would be, if he’d never left, if he had lived. You don’t think you would have run away from home and down the aisle with the first man who stood in front of you. Later, after he reveals his true identity to you, if you were to “accidentally” let him fall down the stairs, knowing the life you’ve lived, a life he caused, would anyone blame you?

Never mind. Instead, you are a thirty-four-year-old heroin addict named Estelle Solomon whose father once faked his own death. He did it before he had you, but you don’t know it yet. Today is the day that he’ll tell you. Sometime in the late afternoon. For now, you are lying, unaware, on a daybed in the basement of your family’s Harlem brownstone, where you’ve lived for the last eight years, since a judge made your parents the legal guardians of your daughter. You had begged your father to let you and Caren move into the garden apartment, right above you, because it has windows. But he screamed, “Is what you need windows fah? Why, when you spend fi yuh whole life asleep?” Instead, they kept your daughter upstairs with them and left you to stay in the basement. Your father seems determined to keep you alive but just as eager to bury you.

You weren’t always such an embarrassment. You worked very hard to become one.

You have been an addict for many years now. But before your mother died, you were also an artist. You could still hustle. You were taking and selling pictures. Occasionally, someone would put your photos on display in a café or a small gallery. Every once in a while you sold something, made a little money, and even came home and gave it to your father, telling him to buy something nice for your daughter with the money your art made you. He would never take it. Worse, he would throw it down on the floor in front of you, so both he and your mother would have to watch you gather the scattered bills from all over the room.

“After me nuh know where that money come from. Me nuh wan’ know what someone like you have fi do to come by it.”

Someone like you. He stopped short of calling you a whore for the sake of your mother. But you could feel how badly he wanted to.

You have always sensed a lie behind your parents’ words, have always suspected that their Jamaica was a place that did not exist. You have always wondered why they never chose, in all these years, to return to that island so perfect. Instead it was always the right weapon to throw in your face, always the only answer to their problems, their main problem always being you.

When you were younger, you would scream back at them that if in Jamaica, the daughters were pure, saved themselves until marriage, stood by their mother’s side every day in the kitchen and watched them cook, brought their father his slippers when he got home from the store, went to church every Sunday, never refused to recite the Lord’s Prayer at the table before a meal, didn’t proclaim themselves agnostics, wanted to be wives instead of artists, always agreed to stack canned food on the shelves of their father’s store after school, didn’t stand under the streetlights at night talking to boys from the block, did their own laundry and their father’s too, did not jump between their parents and cuss their father out every time he raised his voice at their mother, did not promise to kill their father if he dared threaten—only threatened—to one day slap their mother in the face. If in Jamaica, daughters did not run away from home and return pregnant by a man twice their age, did not go out partying instead of staying home with their newborn child, did not walk down the street in skirts so short they barely covered their pum-pum, did not make their mother cry and waste away with worry, never did drugs and if they did, were never so weak that they would become addicted. If in Jamaica, daughters were churned out of factories without the slightest defect, why the fuck didn’t they just go back there and leave you alone?

When your father tells you his secret, that he is not really Stanford Solomon, and therefore you in turn cannot be Estelle Solomon, that your family does not even exist, you will have your answer. And it is perfect.

Say you are an eighteen-year-old college student named Caren who lives in a Harlem brownstone with your mother, who is a heroin addict, and your wheelchair-bound Jamaican grandfather who faked his own death, but you won’t know it for a few hours.

Every morning when you wake up, you remember that your grandmother Adele, the person you loved above everyone else in this world, is gone. She worked so hard to shield you from your mother. She loved you so deep it almost rendered your mother’s love supplementary—a bonus—so that the times when Estelle was lucid enough to pay attention to you felt like a holiday, a special occasion. Every child knows that holidays don’t last. By the time you were eight, you had stopped being disappointed.

You don’t begrudge your mother. You can see how hard she is trying. You know she hates living in your grandfather’s house, but in the month since your grandma died, she no longer vanishes for days at a time, returning with no explanation. For the first time in your life, with the exception of an hour a day when she sneaks outside to score, you know exactly where you’ll find her. Knowing should comfort you, but on the rare occasion when you go to the basement and stare at her, passed out on the daybed, you can’t help but wish it had been her who had a heart attack instead of your grandmother. You think, What a waste of a life. The same words you’d overhear your grandmother mumble when she talked about Estelle. You are ashamed of your thoughts. Most of the time Estelle invokes pity in you, and you conclude that’s worse than hatred, for a child to pity their mother.

Later, when your grandfather tells you that he was born Abel Paisley and not Stanford Solomon, you will understand why your grandmother was so disgusted by Estelle’s addiction. Other people are so desperate to make a better life that they are willing to steal one, while your mother is fine with throwing hers away. Perhaps, a life does not belong exclusively to one person, you learn. Look how easily it can be passed from one person to the next until every bit of it is put to good use. You will wonder if there is someone out there who would wear your life better.

But before that, you notice that from the moment you wake up, your grandpa is acting strange. You had been begging him to get a home health aide for the last year because caring for him was getting to be too much for your grandmother, and now it is too much for you. All of a sudden there is one sitting with him at the kitchen table. He is giddy as he says her name to you, Irene, and you wonder if it has been too long since he’s seen a woman he wasn’t related to.

You are about to smile at Irene when you notice that she doesn’t bother to smile at you, barely tilts her head in your direction, before she returns to reading your grandpa’s newspaper. If your grandmother were here, the two of you would go upstairs and talk about this woman. For a moment, you imagine all of the things you would say about her, until you remember that your grandmother is gone. Briefly you contemplate going down to the basement and telling your mother about Irene, but that would be as exciting as talking to a corpse.

Since your grandmother left you, you’ve found it hard to think about anything else besides getting away from this family. So much so, you’ve started sleeping with one of your professors at City College. It helps the fantasy of running away. The irony that you might be following in your mother’s footsteps doesn’t escape you. Your father had been a professor, but your mother had been a high school girl who’d just had a bunch of college friends. Your birth cost him his marriage and his reputation, and even though he was kind the handful of times you visited him, you know he resented you. You speak to him only on holidays now, even though he just lives in Queens. But still, you want him to be proud of you. You are actually going to get a degree one day. You are actually going to leave this house.

Sometimes you imagine a scenario in which your professor leaves his wife and four children and buys a condo for the two of you in downtown Brooklyn. You are not sure what you would say if he were actually to propose this to you. He hasn’t talked about leaving his wife, hasn’t said he loves you. You might think less of him if he did. Besides, you have no intention of trading your dysfunctional family for another, being the reluctant stepmother to four resentful white kids. In your family, you are known as the smart one for a reason.

Now let’s say that you are a dead woman, six years on the other side, whose husband let you believe he was dead. When you were alive, they called you Vera, but here there is no need for names. You did not know the truth about your husband until your own death, but the timing of the knowledge made it no less infuriating. You have analyzed all the years you spent mad with guilt, thinking you were the one who sent him to his grave.

Death is just one long therapy session. You have gone over every second of your life and divided them into the misery you caused and the misery others caused you. You have been waiting for six years for this motherfucker to die, and you know that the day has finally arrived.

You look at the elaborate theater that your former husband is producing and you laugh (or you imagine yourself laughing; you no longer have a mouth or a face). He has asked the women down to the brownstone’s parlor. He has your daughter—your daughter who he barely even knew—help him move from his wheelchair to his favorite rocking chair, which he thinks makes him appear wise. Clearly, none of the women want to be there. The three of them settle side by side on a crushed-velvet settee barely listening, unaware of their blood connection.

You are there in the room with them, waiting for Abel to gather up his nerve. You have decided to choose one person in his house to be the catalyst of his death, to be briefly possessed by you long enough to get the deed done, but the question of who has stumped you. Who will hurt him the most?

You look at your own daughter, Irene, think she’s owed the revenge, but you can see both the past and the future and know that giving her guilt to carry is not doing her any favors. There is a cruel impulse inside her, one that you gave her, that you do not want to feed. You know that most of her misery was brought about by you. When she dies, you will face your own reckoning, but for now you have no plans to ruin her life any further.

You look at the other two women, his daughter and granddaughter, the products of the weak woman he married after you. You have passed her in the other place, for she’s dead now too. You thought you’d have harsh words for her, that her day of reckoning would come, but you mostly feel sorry for her. You can feel her pining for Abel, pleading with you to spare him, until you’ve recently had no choice but to shut her out.

You are so close to Abel as he tells them you can smell the Wray & Nephew rum on his breath, but he can’t see or sense you. When he says the words I was born Abel Paisley, you see your daughter shake her head. It will take her a while to understand that her father was alive all those years and left her behind to suffer with you. After he says the words I was born Abel Paisley, his daughter Estelle exhales deeply, tears form in her eyes, but then she just bursts out laughing. For the first time in her life, she actually looks at her father with gratitude. She actually turns to the old man and says, “Thank you.” Estelle puts her arms around her daughter, Caren, who, after he tells them, begins to cry.

Irene stands up and crosses the room, kneeling before Abel, and for a moment you worry that she will choke the life out of him before you even have a chance to. Instead she studies his face. She is thinking about the picture, the one under the mango tree, and when she recognizes him, she walks out of the room, collects her purse from the hall, and leaves for good, slamming the front door so hard it shakes you. You look at the two girls left in the room and reassure yourself that no matter which one ends him, it will actually be you. If only he could see you as he’s falling. If you still had a mouth, you would be laughing. If you still had a body, you would dance.

Descriere

*An Entertainment Weekly and LitHub Most Anticipated Book of 2020 Pick and Buzz Magazine’s Top New Book of the New Decade*