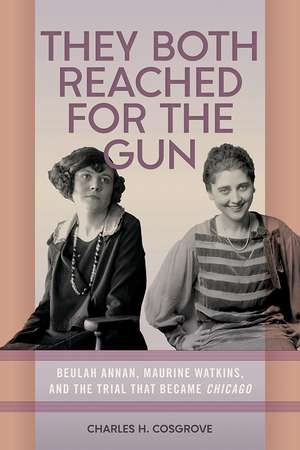

They Both Reached for the Gun: Beulah Annan, Maurine Watkins, and the Trial That Became Chicago

Autor Charles H. Cosgroveen Limba Engleză Paperback – 7 iun 2024

In 1924 Beulah Annan was arrested for killing her lover, Harry Kalsted. Six weeks later, a jury acquitted her of murder. Inspired by the sordid event, trial, and acquittal, reporter Maurine Watkins wrote the play Chicago, a Broadway hit that was adapted several times. Through a fresh retelling of Annan’s story and Watkins’s play, Charles H. Cosgrove provides the first critical examination of the criminal case and an exploration of the era’s social assumptions that made the play’s message so plausible in its time. Cosgrove expertly combines inquest and police records, and interviews with Annan’s relatives, to analyze the participants, the trial, and the play. Although no one will ever know what really happened in that Kenwood apartment, Cosgrove’s interrogation shows how sensationalized Watkins’s writing was. Her reporting on the Annan case perpetuated falsehoods about Annan’s so-called “confession,” and her play inaccurately portrayed Chicago’s criminal justice system. Cosgrove challenges the portrait of Annan as a killer who got away with murder and of Watkins as a savvy reporter and precocious playwright. He exposes the weaknesses of the case against Annan and vindicates the jury that tried her.

Preț: 135.90 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 204

Preț estimativ în valută:

26.01€ • 28.27$ • 21.86£

26.01€ • 28.27$ • 21.86£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 01-15 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780809339389

ISBN-10: 0809339382

Pagini: 240

Ilustrații: 39

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.39 kg

Ediția:First Edition

Editura: Southern Illinois University Press

Colecția Southern Illinois University Press

ISBN-10: 0809339382

Pagini: 240

Ilustrații: 39

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.39 kg

Ediția:First Edition

Editura: Southern Illinois University Press

Colecția Southern Illinois University Press

Notă biografică

Charles H. Cosgrove is emeritus professor of early Christian literature at Garrett Seminary in Evanston, Illinois. He is the author of numerous books, most recently Fortune and Faith in Old Chicago: A Dual Biography of Mayor Augustus Garrett and Seminary Founder Eliza Clark Garrett, and Music at Social Meals in Greek and Roman Antiquity. A lifelong native of the Chicago area, he is an aficionado of the city’s history and makes occasional appearances in the area’s music venues as a jazz trombonist.

Extras

INTRODUCTION

On April 3, 1924, the Chicago police arrested a woman named Beulah Annan for killing a man named Harry Kalsted in her Kenwood apartment on the city’s south side. Harry was Beulah’s lover, and the two of them had consumed a good deal of wine during their afternoon rendezvous, while Beulah’s husband was at work. Police recovered a gun and a blood-stained jazz record.

Beulah’s arrest became immediate front-page news in Chicago and across the country. Six weeks later a Chicago jury acquitted her of murder, and the story was again headline news. A young reporter named Maurine Watkins covered Beulah’s case for the Chicago Tribune and subsequently wrote a play about it. Watkins thought Beulah was guilty and said so. So did her play, Chicago, since its plot was widely known to be based on Beulah’s case.

The play, which became a Broadway hit, was a satire about the Chicago criminal justice system, and it carried a social message, namely, that the city’s falsely chivalric and sentimental all-male juries were making a mockery of the courts by setting free virtually every woman tried for murder. The play lampooned the press, too, for turning crime news into entertainment.

Watkins’s 1926 play was turned into a silent film in 1927, a sound movie starring Ginger Rogers in 1942, and a Bob Fosse musical in the 1970s that was revived to great acclaim in the 1990s and then transformed into the 2002 Rob Marshall movie Chicago, one of most successful movie musicals of all time. Since Marshall’s version, there has been renewed curiosity about the origins of the drama. Besides innumerable webpages, many books have taken up different parts of that history, especially the facts about Beulah Annan. A few have sought to place her in the social context of 1920s Chicago, and some have noted that Maurine Watkins based her play on her reporting on criminal cases involving women, especially the Annan case.

Until now, however, no one has offered a critical examination of the case against Beulah Annan or an exploration of the social assumptions that made the message of Chicago plausible in its own time. My aim is to accomplish these things through a fresh retelling of the story of Beulah Annan and the play she inspired.

Watkins’s message reflected assumptions influenced by the era in which she lived and the newspaper for which she worked. As she herself once noted in an interview with the New York World (January 16, 1927), the Chicago Tribune’s stance on criminal cases was always pro-prosecution. As a Tribune reporter, Watkins reflected this attitude in her coverage of Annan, and she did the same in her play. Chicago portrays its representative police character as an earnest but dumb servant of the law and its representative assistant-state’s-attorney character as a shrewd, honest but weary pursuer of truth and justice engaged in a losing battle against dynamics he cannot control—guilty lying defendants, lying money-grubbing defense attorneys, and misguided juries who become willing fools whenever they are confronted with a female defendant.

The play’s message about the justice system also resonated with the times. For years, Chicagoans had been told that women were committing murder at alarming rates and getting away with it. The papers, usually quoting prosecutors, stoked public anger by quoting raw acquittal figures without context, giving the impression that juries were doing nothing to stem the tide of female killers. Many people believed that the jury system had become an ineffective instrument of justice generally; or at least they worried that this might be so. As a highly regarded 1931 federal study of crime and the criminal-justice system in 1920s Chicago noted, the “news value” of jury trials had fostered an erroneous popular idea about their role in the criminal-justice system. The public had the false impression that “acquittals by juries constitute the predominant mode or method whereby men accused of crime escape conviction and that the jury trial is the weak spot in the administration [of justice].” These observations explain why the premise of Watkins’s play seemed so plausible. The play purported to lay bare all the behind-the-scenes chicanery that was supposedly causing bad jury verdicts in trials of female murder defendants. Similar concerns about juries were prevalent in other cities as well, which gave the play’s message broad appeal. Indeed, theater critics across the country observed that the satire’s ridicule of the criminal justice system in Chicago probably applied to other metropolises, too.

The path of the main character Roxie Hart from arrest to trial to freedom was meant to be typical, and it was widely recognized at the time—from both press coverage of the play and public comments by Watkins herself—that Roxie was based very specifically on Beulah Annan, whose own path through the justice process was supposed to be emblematic. There was even a certain parallel between the way Watkins constructed the plot of the 1926 play and her reporting on the 1924 Annan case. In the opening scene of Chicago, she showed Roxie committing cold-blooded murder, thus leaving no doubt about her guilt in the mind of the audience. The “opening scene” of the real-life Annan case was reported in the Chicago Tribune on the basis of a confession that Annan had allegedly made to the investigating police and prosecutors. The Tribune’s first article about the case—unsigned and not necessarily by Watkins—reported this allegation as fact; subsequent signed articles by Watkins took this fact for granted and used it against Annan. Thus, when Annan herself later talked directly to reporters and claimed self-defense, Watkins told her readers that Annan had retracted her confession, implying that she had concocted a phony defense. The plot structure of Chicago mirrors this: it presents the true facts to the audience right from the start and shows the defendant who has admitted them subsequently and outrageously disavowing them. There was, however, an important difference between the real-life case and that of the play. When the actual text of Annan’s so-called confession became public at an inquest, it revealed that the prosecutors had misrepresented Annan’s words. Watkins’s reporting never pointed out this discrepancy; nor did the other papers. Nor have subsequent re-tellers of Annan’s story.

Investigating the history of Chicago affords a revealing look into ways in which the press, prosecutors, and ultimately even the theater shaped perceptions of crime and criminal justice in 1920s Chicago. In Watkins’s opinion and that of George Pierce Baker, her renowned mentor in drama, the play was a piece of biting social critique about a serious subject, a comedy with an earnest message—an exposé. The satire was also received by critics as a weighty matter. Yet in reality, the problem it attacked was something of a red herring and not the “the weak spot” in the administration of justice in 1920s Chicago. By the same token, the play’s singular focus on a minor issue, which it hyped as an outrage, was a sort of misdirection that reinforced what was already a general public obliviousness to more serious conditions in the city’s criminal-justice system. When Chicago’s corrupt mayor William Hale Thompson told the press that Watkins was “excellently suited to tell the world all it need know about the city of Chicago,” he had reason to be grateful that her satirical exposé focused on a relatively small matter and seemed to exonerate Chicago’s police and prosecutors of any systematically corrupt tendencies. Of course, Watkins was not an investigative reporter, much less a sociologist. Having absorbed prevailing opinions at the Tribune, with which she may already have been sympathetic, she mirrored them in the message of her play.

Among the more serious problems with criminal justice system in 1920s Chicago were the police’s routine use of violence to extort confessions from criminal suspects and the system’s pervasive racial bias against African Americans, especially African American men. Roxie Hart was manifestly white, as were all the other characters in Chicago, as if the main setting of the dramatic action, the women’s wing of Cook County Jail, held no African American women. Yet at one point Roxie complains that she might have to eat “with the wops and the n-----s.” This was meant to draw guffaws from an audience that was expected to agree with Roxie’s white racist sentiments and to find it humorously pretentious that a lowlife like her should be so discriminating about the company she kept in jail. Hence, to the extent that the play carried messages about race, it exploited racism for laughs while insinuating that racism played no role in Chicago’s criminal-justice operations, since Chicago juries supposedly let 98 percent of all female murderers go free, whatever their race.

Although Watkins was actually not “excellently suited” to offer a behind-the-scenes exposé of Chicago’s criminal-justice process, as an avid newspaper reader and a media insider, she was well-equipped to comment on newspapers as money-making enterprises. Her play described the methods of the press in turning crime news into lucrative entertainment, and it made fun of the gushingly sympathetic, so-called “sob-sister” reporting that the tabloids lavished on female defendants. During her days as a reporter, Watkins herself had not been a sob sister. The Chicago Tribune did not encourage that sort of reporting by its female staff; and as one of the staider papers, it reported on homicides in matter-of-fact prose. Watkins’s articles about Annan mixed matter-of-fact prose with touches of wry wit and light mockery. In this respect, she was something of a trailblazer in women’s crime journalism, and her experiments in journalistic tone presaged the satirical approach she used in Chicago.

A close look at reporting styles in the news coverage of Annan also turns up another interesting feature of 1920s journalism. Although news editors at papers with strict journalistic standards demanded factual exactitude about the who, what, when, and where of a story, they granted latitude in quotation. It was deemed sufficient for reporters to use their own words in quoting a subject, so long as they succeeded in conveying the “gist” of what someone said. Loose paraphrase was regularly placed between quotation marks, and no one in the news business seems to have had any reservations about this practice. Even handbooks for would-be reporters written by university professors—academics devoted to raising the standards of journalism—condoned this method of “paraquotation” (my term). As for newspaper readers, they had no way of knowing and probably did not even suspect that many of the quotations they encountered in news articles, across a wide range of topics, were free paraphrases. The possibilities for misrepresentation were rife in paraquotation, and reporters and rewrite staff at certain tabloids felt free to create quotations out of whole cloth.

Creative quotation was certainly practiced by reporters who covered Beulah Annan. To varying degrees, the press fashioned her into a fictionalized character before Watkins turned her into the fictional Roxie Hart. This makes it difficult to pierce the veil to the historical person. Yet the use of critical methods—such as testing quotations against independently established facts, including examples of Annan’s own style of speaking, and comparing quotations in different newspaper accounts that claim to report the same interview—makes it possible to discover places in the news coverage where Annan’s own voice comes through.

By providing a more accurate and detailed history of Beulah Annan, I may give the impression that my aim is to cultivate sympathy for her and even to vindicate her. As for vindication, I leave it to readers to form conclusions, if any, about whether Annan was guilty or innocent of the crime for which she was tried. Having thoroughly examined the evidence myself, I find grounds for reasonable doubt. Hence, one of my aims is to vindicate the jury that tried Annan by showing that the prosecution’s case, indeed the evidence as a whole, was insufficient to warrant a conviction.

As for sympathy, Annan’s rather sad life history may evoke readers’ sympathy at points, unsympathy at other points, indeed a set of mixed feelings overall, along with a good deal of uncertainty about the most crucial thing—whether she killed Harry Kalsted in a drunken rage or in a drunken but genuine fear for her life. I have made every effort to be even-handed in my treatment of her and to proceed similarly with Maurine Watkins, providing context that helps explain each woman’s attitudes and decisions. It may be worth mentioning that readers who participated in the review process for the book arrived at contrary opinions about Annan and Watkins, which ranged from encouraging me to go harder on Watkins by emphasizing how she exploited Annan, to urging me to treat Watkins more sympathetically and to be more severe with Annan.

Beulah Annan would be of little historical importance today had not Watkins’s play made a social message out of her, claiming that Chicago was realistic fiction, “real, all through,” “all straight, without any idea of exaggeration.” In other words, the play was supposed to be an exposé that revealed the truth about Beulah and woman like her, and in so doing presented a scathing behind-the-scenes look at Chicago’s criminal-justice system. While the play was also a comedy, its humor derived not from comedic distortion, so Watkins alleged, but from a realistic display of events that were a mockery in themselves, a travesty of justice. These claims deserve critical examination—a thorough historical investigation of all the relevant facts they purport to represent. The chapters to follow take up this task, and in this respect the present book offers an assessment of Chicago as a social satire, both as Watkins conceived it and as 1920s theater critics received it.

[end of excerpt]

On April 3, 1924, the Chicago police arrested a woman named Beulah Annan for killing a man named Harry Kalsted in her Kenwood apartment on the city’s south side. Harry was Beulah’s lover, and the two of them had consumed a good deal of wine during their afternoon rendezvous, while Beulah’s husband was at work. Police recovered a gun and a blood-stained jazz record.

Beulah’s arrest became immediate front-page news in Chicago and across the country. Six weeks later a Chicago jury acquitted her of murder, and the story was again headline news. A young reporter named Maurine Watkins covered Beulah’s case for the Chicago Tribune and subsequently wrote a play about it. Watkins thought Beulah was guilty and said so. So did her play, Chicago, since its plot was widely known to be based on Beulah’s case.

The play, which became a Broadway hit, was a satire about the Chicago criminal justice system, and it carried a social message, namely, that the city’s falsely chivalric and sentimental all-male juries were making a mockery of the courts by setting free virtually every woman tried for murder. The play lampooned the press, too, for turning crime news into entertainment.

Watkins’s 1926 play was turned into a silent film in 1927, a sound movie starring Ginger Rogers in 1942, and a Bob Fosse musical in the 1970s that was revived to great acclaim in the 1990s and then transformed into the 2002 Rob Marshall movie Chicago, one of most successful movie musicals of all time. Since Marshall’s version, there has been renewed curiosity about the origins of the drama. Besides innumerable webpages, many books have taken up different parts of that history, especially the facts about Beulah Annan. A few have sought to place her in the social context of 1920s Chicago, and some have noted that Maurine Watkins based her play on her reporting on criminal cases involving women, especially the Annan case.

Until now, however, no one has offered a critical examination of the case against Beulah Annan or an exploration of the social assumptions that made the message of Chicago plausible in its own time. My aim is to accomplish these things through a fresh retelling of the story of Beulah Annan and the play she inspired.

Watkins’s message reflected assumptions influenced by the era in which she lived and the newspaper for which she worked. As she herself once noted in an interview with the New York World (January 16, 1927), the Chicago Tribune’s stance on criminal cases was always pro-prosecution. As a Tribune reporter, Watkins reflected this attitude in her coverage of Annan, and she did the same in her play. Chicago portrays its representative police character as an earnest but dumb servant of the law and its representative assistant-state’s-attorney character as a shrewd, honest but weary pursuer of truth and justice engaged in a losing battle against dynamics he cannot control—guilty lying defendants, lying money-grubbing defense attorneys, and misguided juries who become willing fools whenever they are confronted with a female defendant.

The play’s message about the justice system also resonated with the times. For years, Chicagoans had been told that women were committing murder at alarming rates and getting away with it. The papers, usually quoting prosecutors, stoked public anger by quoting raw acquittal figures without context, giving the impression that juries were doing nothing to stem the tide of female killers. Many people believed that the jury system had become an ineffective instrument of justice generally; or at least they worried that this might be so. As a highly regarded 1931 federal study of crime and the criminal-justice system in 1920s Chicago noted, the “news value” of jury trials had fostered an erroneous popular idea about their role in the criminal-justice system. The public had the false impression that “acquittals by juries constitute the predominant mode or method whereby men accused of crime escape conviction and that the jury trial is the weak spot in the administration [of justice].” These observations explain why the premise of Watkins’s play seemed so plausible. The play purported to lay bare all the behind-the-scenes chicanery that was supposedly causing bad jury verdicts in trials of female murder defendants. Similar concerns about juries were prevalent in other cities as well, which gave the play’s message broad appeal. Indeed, theater critics across the country observed that the satire’s ridicule of the criminal justice system in Chicago probably applied to other metropolises, too.

The path of the main character Roxie Hart from arrest to trial to freedom was meant to be typical, and it was widely recognized at the time—from both press coverage of the play and public comments by Watkins herself—that Roxie was based very specifically on Beulah Annan, whose own path through the justice process was supposed to be emblematic. There was even a certain parallel between the way Watkins constructed the plot of the 1926 play and her reporting on the 1924 Annan case. In the opening scene of Chicago, she showed Roxie committing cold-blooded murder, thus leaving no doubt about her guilt in the mind of the audience. The “opening scene” of the real-life Annan case was reported in the Chicago Tribune on the basis of a confession that Annan had allegedly made to the investigating police and prosecutors. The Tribune’s first article about the case—unsigned and not necessarily by Watkins—reported this allegation as fact; subsequent signed articles by Watkins took this fact for granted and used it against Annan. Thus, when Annan herself later talked directly to reporters and claimed self-defense, Watkins told her readers that Annan had retracted her confession, implying that she had concocted a phony defense. The plot structure of Chicago mirrors this: it presents the true facts to the audience right from the start and shows the defendant who has admitted them subsequently and outrageously disavowing them. There was, however, an important difference between the real-life case and that of the play. When the actual text of Annan’s so-called confession became public at an inquest, it revealed that the prosecutors had misrepresented Annan’s words. Watkins’s reporting never pointed out this discrepancy; nor did the other papers. Nor have subsequent re-tellers of Annan’s story.

Investigating the history of Chicago affords a revealing look into ways in which the press, prosecutors, and ultimately even the theater shaped perceptions of crime and criminal justice in 1920s Chicago. In Watkins’s opinion and that of George Pierce Baker, her renowned mentor in drama, the play was a piece of biting social critique about a serious subject, a comedy with an earnest message—an exposé. The satire was also received by critics as a weighty matter. Yet in reality, the problem it attacked was something of a red herring and not the “the weak spot” in the administration of justice in 1920s Chicago. By the same token, the play’s singular focus on a minor issue, which it hyped as an outrage, was a sort of misdirection that reinforced what was already a general public obliviousness to more serious conditions in the city’s criminal-justice system. When Chicago’s corrupt mayor William Hale Thompson told the press that Watkins was “excellently suited to tell the world all it need know about the city of Chicago,” he had reason to be grateful that her satirical exposé focused on a relatively small matter and seemed to exonerate Chicago’s police and prosecutors of any systematically corrupt tendencies. Of course, Watkins was not an investigative reporter, much less a sociologist. Having absorbed prevailing opinions at the Tribune, with which she may already have been sympathetic, she mirrored them in the message of her play.

Among the more serious problems with criminal justice system in 1920s Chicago were the police’s routine use of violence to extort confessions from criminal suspects and the system’s pervasive racial bias against African Americans, especially African American men. Roxie Hart was manifestly white, as were all the other characters in Chicago, as if the main setting of the dramatic action, the women’s wing of Cook County Jail, held no African American women. Yet at one point Roxie complains that she might have to eat “with the wops and the n-----s.” This was meant to draw guffaws from an audience that was expected to agree with Roxie’s white racist sentiments and to find it humorously pretentious that a lowlife like her should be so discriminating about the company she kept in jail. Hence, to the extent that the play carried messages about race, it exploited racism for laughs while insinuating that racism played no role in Chicago’s criminal-justice operations, since Chicago juries supposedly let 98 percent of all female murderers go free, whatever their race.

Although Watkins was actually not “excellently suited” to offer a behind-the-scenes exposé of Chicago’s criminal-justice process, as an avid newspaper reader and a media insider, she was well-equipped to comment on newspapers as money-making enterprises. Her play described the methods of the press in turning crime news into lucrative entertainment, and it made fun of the gushingly sympathetic, so-called “sob-sister” reporting that the tabloids lavished on female defendants. During her days as a reporter, Watkins herself had not been a sob sister. The Chicago Tribune did not encourage that sort of reporting by its female staff; and as one of the staider papers, it reported on homicides in matter-of-fact prose. Watkins’s articles about Annan mixed matter-of-fact prose with touches of wry wit and light mockery. In this respect, she was something of a trailblazer in women’s crime journalism, and her experiments in journalistic tone presaged the satirical approach she used in Chicago.

A close look at reporting styles in the news coverage of Annan also turns up another interesting feature of 1920s journalism. Although news editors at papers with strict journalistic standards demanded factual exactitude about the who, what, when, and where of a story, they granted latitude in quotation. It was deemed sufficient for reporters to use their own words in quoting a subject, so long as they succeeded in conveying the “gist” of what someone said. Loose paraphrase was regularly placed between quotation marks, and no one in the news business seems to have had any reservations about this practice. Even handbooks for would-be reporters written by university professors—academics devoted to raising the standards of journalism—condoned this method of “paraquotation” (my term). As for newspaper readers, they had no way of knowing and probably did not even suspect that many of the quotations they encountered in news articles, across a wide range of topics, were free paraphrases. The possibilities for misrepresentation were rife in paraquotation, and reporters and rewrite staff at certain tabloids felt free to create quotations out of whole cloth.

Creative quotation was certainly practiced by reporters who covered Beulah Annan. To varying degrees, the press fashioned her into a fictionalized character before Watkins turned her into the fictional Roxie Hart. This makes it difficult to pierce the veil to the historical person. Yet the use of critical methods—such as testing quotations against independently established facts, including examples of Annan’s own style of speaking, and comparing quotations in different newspaper accounts that claim to report the same interview—makes it possible to discover places in the news coverage where Annan’s own voice comes through.

By providing a more accurate and detailed history of Beulah Annan, I may give the impression that my aim is to cultivate sympathy for her and even to vindicate her. As for vindication, I leave it to readers to form conclusions, if any, about whether Annan was guilty or innocent of the crime for which she was tried. Having thoroughly examined the evidence myself, I find grounds for reasonable doubt. Hence, one of my aims is to vindicate the jury that tried Annan by showing that the prosecution’s case, indeed the evidence as a whole, was insufficient to warrant a conviction.

As for sympathy, Annan’s rather sad life history may evoke readers’ sympathy at points, unsympathy at other points, indeed a set of mixed feelings overall, along with a good deal of uncertainty about the most crucial thing—whether she killed Harry Kalsted in a drunken rage or in a drunken but genuine fear for her life. I have made every effort to be even-handed in my treatment of her and to proceed similarly with Maurine Watkins, providing context that helps explain each woman’s attitudes and decisions. It may be worth mentioning that readers who participated in the review process for the book arrived at contrary opinions about Annan and Watkins, which ranged from encouraging me to go harder on Watkins by emphasizing how she exploited Annan, to urging me to treat Watkins more sympathetically and to be more severe with Annan.

Beulah Annan would be of little historical importance today had not Watkins’s play made a social message out of her, claiming that Chicago was realistic fiction, “real, all through,” “all straight, without any idea of exaggeration.” In other words, the play was supposed to be an exposé that revealed the truth about Beulah and woman like her, and in so doing presented a scathing behind-the-scenes look at Chicago’s criminal-justice system. While the play was also a comedy, its humor derived not from comedic distortion, so Watkins alleged, but from a realistic display of events that were a mockery in themselves, a travesty of justice. These claims deserve critical examination—a thorough historical investigation of all the relevant facts they purport to represent. The chapters to follow take up this task, and in this respect the present book offers an assessment of Chicago as a social satire, both as Watkins conceived it and as 1920s theater critics received it.

[end of excerpt]

Cuprins

CONTENTS

List of Figures

Preface

A Note on Names

Acknowledgments

Introduction

1. Beulah Mae

2. A Shooting

3. An Alleged Confession

4. Police and Prosecutors Shape the Narrative

5. Inquest into the Death of Harry Kalsted

6. Finding Beulah behind the Press’s Tropes and Paraquotations

7. Maurine Watkins’s News with Wit

8. Back in Owensboro

9. Popular Opinions about Jury Bias in Favor of Women

10. Beulah Annan Goes to Trial

11. Watkins’s Tendentious Reporting on the Annan Trial

12. A Play Is Born

13. The Truth about Chicago’s Criminal Justice System

14. The Short Unhappy Finish to Beulah’s Life

15. Beulah Remembered as Roxie

16. Bob Fosse’s Musical Remake of Maurine Watkins’s Play

Postscript

Abbreviations

Notes

Bibliography

List of Figures

Preface

A Note on Names

Acknowledgments

Introduction

1. Beulah Mae

2. A Shooting

3. An Alleged Confession

4. Police and Prosecutors Shape the Narrative

5. Inquest into the Death of Harry Kalsted

6. Finding Beulah behind the Press’s Tropes and Paraquotations

7. Maurine Watkins’s News with Wit

8. Back in Owensboro

9. Popular Opinions about Jury Bias in Favor of Women

10. Beulah Annan Goes to Trial

11. Watkins’s Tendentious Reporting on the Annan Trial

12. A Play Is Born

13. The Truth about Chicago’s Criminal Justice System

14. The Short Unhappy Finish to Beulah’s Life

15. Beulah Remembered as Roxie

16. Bob Fosse’s Musical Remake of Maurine Watkins’s Play

Postscript

Abbreviations

Notes

Bibliography

Recenzii

“Cosgrove shines a dazzling spotlight on the historical distortions behind the musical Chicago and its source material. With authority and clarity, he argues there never was a Jazz Age Chicago where beautiful women routinely got away with murder. On trial here: the pushback against American women’s social progress.”—Marcia Biederman, author of The Disquieting Death of Emma Gill: Abortion, Death, and Concealment in Victorian New England

“They Both Reached for the Gun is a fascinating exploration of the history behind Chicago, the musical based loosely on the 1924 conviction of Beulah Annan for her lover's murder. Through a careful reexamination of the case, the sensational press coverage, and the transformation of the actual events into entertainment, Cosgrove investigates the sometimes-unhealthy relationship between crime news and entertainment.”—Ann Durkin Keating, North Central College

“In a smooth and flowing style, Cosgrove’s rich insight into a troubled woman’s existence culminating in a questionable indictment and ‘trial-by-press’ presumption of guilt, provides readers with a sobering reassessment of the case, with a glimpse into the era and tabloid culture of the Roaring Twenties.”—Richard C. Lindberg, author of Tales of Forgotten Chicago

“They Both Reached for the Gun is a fascinating exploration of the history behind Chicago, the musical based loosely on the 1924 conviction of Beulah Annan for her lover's murder. Through a careful reexamination of the case, the sensational press coverage, and the transformation of the actual events into entertainment, Cosgrove investigates the sometimes-unhealthy relationship between crime news and entertainment.”—Ann Durkin Keating, North Central College

“In a smooth and flowing style, Cosgrove’s rich insight into a troubled woman’s existence culminating in a questionable indictment and ‘trial-by-press’ presumption of guilt, provides readers with a sobering reassessment of the case, with a glimpse into the era and tabloid culture of the Roaring Twenties.”—Richard C. Lindberg, author of Tales of Forgotten Chicago

Descriere

They Both Reached for the Gun sheds new light on the sordid story of the 1924 shooting of Harry Kalsted, Beulah Annan's trial, the participants, and reporter Maurine Watkins’s 1926 play Chicago, which was later adapted to the Rob Marshall movie Chicago, one of most successful movie musicals of all time.