Things I Didn't Know: Realice su Potencial Eterno Cada Da

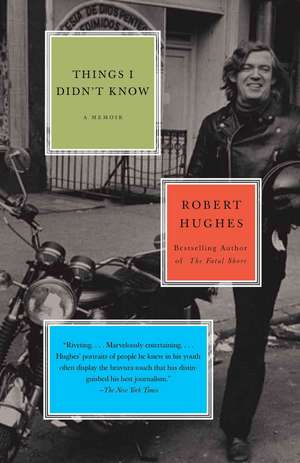

Autor Robert Hughesen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 noi 2007

Preț: 120.26 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 180

Preț estimativ în valută:

23.01€ • 23.78$ • 19.15£

23.01€ • 23.78$ • 19.15£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 04-18 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307385987

ISBN-10: 0307385981

Pagini: 395

Dimensiuni: 134 x 204 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.31 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 0307385981

Pagini: 395

Dimensiuni: 134 x 204 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.31 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Notă biografică

Robert Hughes was born in Australia in 1938. Since 1970 he has lived and worked in the United States, where until 2001 he was chief art critic for Time, to which he still contributes. His books include The Shock of the New, The Fatal Shore, Nothing if Not Critical, Barcelona, and Goya. He is the recipient of a number of awards and prizes for his work.

Extras

chapter one

A Bloody Expat

The most extreme change in my life occurred, out of a blue sky, on the 30th of May, 1999, a little short of my sixty-first birthday.

I was in Western Australia, where I had been making a TV series about my native country. I had taken a couple of days off, and chosen to spend them fishing off the shore of a resort named Eco Beach with a friend, Danny O’Sullivan, a professional guide. We went after small offshore tuna, with fly rods, in an open skiff. It had been a wonderful day: fish breaking everywhere, fighting fiercely when hooked, and one—a small bluefin, about twenty pounds—kept to be eaten later with the crew in Broome.

Now, after a nap, I was on my way back to the Northern Highway, which parallels the huge flat biscuit of a coast where the desert breaks off into the Indian Ocean.

After about ten kilometers, the red dirt road from Eco Beach ended in a cattle gate. I stopped short of it, got out of the car, unhooked the latching chain, swung the gate open. I got back in the car, drove through, stopped again, got out, and closed the gate behind me. Then I hopped back in the car again and drove out onto the tar and concrete of the Great Northern Highway, cautiously looking both ways in the bright, almost horizontal evening light. No road trains galloping toward me: nothing except emptiness. I turned left, heading north for Broome, on the left side of the road, as people have in Australia ever since 1815, when its colonial governor, an autocratic laird named Lachlan Macquarie, decreed that Australians must henceforth ride and drive on the same side as people did in his native Scotland.

It was still daylight, but only just. I flipped my lights on.

There was no crash, no impact, no pain. It was as though nothing had happened. I just drove off the edge of the world, feeling nothing.

I do not know how fast I was going.

I am not a fast driver, or in any way a daring one. Driving has never been second nature to me. I am pawky, old-maidish, behind the wheel. But I collided, head-on, with another car, a Holden Commodore with two people in the front seat and one in the back. It was dusk, about 6:30 p.m. This was the first auto accident I ever had in my life, and I retain absolutely no memory of it. Try as I may, I can dredge nothing up, not even the memory of fear. The slate is wiped clean, as by a damp rag.

I was probably on the wrong (that is, the right-hand) side of the road, over the yellow line—though not very far over. I say “probably” because, at my trial a year later, the magistrate did not find that there was enough evidence to prove, beyond reasonable doubt, that I had been. The Commodore was coming on at some 90 m.p.h., possibly more. I was approaching it at about 50 m.p.h.. Things happen very quickly when two cars have a closing speed of more than 130 m.p.h. It only takes a second for them to get seventy feet closer to one another. No matter how hard you hit the brakes, there isn’t much you can do.

We plowed straight into one another, Commodore registered 7ex 954 into Nissan Pulsar registered 9 yr 650: two red cars in the desert, driver’s side to driver’s side, right headlamp to right headlamp. I have no memory of this. From the moment of impact for weeks to come, I would have no short-term memory of anything. All I know about the actual collision, until after almost a year, when I saw the remains of my rented car in a junkyard in Broome, is what I was told by others.

The other car spun off the highway, skidded down a shallow dirt slope, and ended up half-hidden in the low desert scrub. Its three occupants were injured, two not seriously. Darren William Kelly, thirty-two, the driver, had just come off a stint working on a fishing boat and was heading south to Port Hedland to find any work he could get. He had a broken tibia. Colin Craig Bowe, thirty-six, a builder’s laborer, was riding in the front seat and sustained a broken ankle. Darryn George Bennett, twenty-four, had been working as a deckhand on the same boat as Kelly, the True Blue. Kelly and Bowe were mates; they had known each other for two years. Neither had known Bennett before. He had heard they were driving south to Port Hedland, and he asked for a ride. He was a young itinerant worker in his midtwenties, whose main skill was bricklaying.

Their encounter with the world of writing only added to their misfortunes. All three were addicts and part-time drug dealers. At the moment of the crash, Bennett, in the backseat, was rolling a “cone” of marijuana, a joint. It may or may not have been the first one to be smoked on what was meant to be a thousand-kilometer drive south.

In any case, they had things in common. They had all done jail time. They were young working-class men living now on that side of the law, now on this: sometimes feral, sometimes bewildered, seldom knowing what the next month, let alone the next birthday, would bring.

Not long after he had recovered from the injuries of the collision, Bennett tried to tear the face off an enemy in a bar with a broken bottle. Bowe, as soon as his injuries had healed, attempted an armed robbery, but was arrested, tried, and sentenced to ten years in jail.

Bennett was by far the worst hurt of the three. The impact catapulted him forward against the restraint of the seat belt and gave him a perforated bowel. He had no skeletal damage. All three of them were able to struggle out of the wreck of the Commodore, which had not rolled over. The effort of doing so was agonizing for Bennett, who collapsed on the verge of the road, his guts flooded with pain.

If the Commodore was badly smashed up, my Nissan Pulsar was an inchoate mass of red metal and broken glass, barely recognizable as having once been a car. When at last I saw it in Broome on the eve of my trial, eleven months later, I couldn’t see how a cockroach could have survived that wreck, let alone a human being.

The car had telescoped. The driver’s seat had slammed forward, pinning me against the steering wheel, which was twisted out of shape by the impact of my body, nearly impaling me on the steering column. Much of the driver’s side of the Pulsar’s body had been ripped away, whether by the initial impact or, later, by the hydraulic tools used by the fire brigade and ambulance crew in their long struggle to free me from the wreckage. It looked like a half-car. It was as though the fat, giant foot of God from the old Monty Python graphics had stamped on it and ground it into the concrete. Later, I would make derogatory noises about “that piece of Jap shit” I’d been driving. I was wrong, of course. The damage had saved my life: the gradual collapse and telescoping of the Nissan’s body, compressed into milliseconds, had absorbed and dissipated far more of the impact energy than a more rigid frame could have done.

Now it was folded around me like crude origami. I could scarcely move a finger. Trapped, intermittently conscious, deep in shock and bloodier than Banquo, I had only the vaguest notion of what had happened to me. Whatever it might have been, it was far beyond my experience. I did not recognize my own injuries, and had no idea how bad they were. As it turned out, they were bad enough. Under extreme impact, bones may not break neatly. They can explode into fragments, like a cookie hit by a hammer, and that’s what happened to several of mine.

The catalog of trauma turned out to be long. Most of it was concentrated on the right-hand side of my body—the side that bore the brunt of the collision. As the front of the Nissan collapsed, my right foot was forced through the floor and doubled underneath me; hours later, when my rescuers were at last able to get a partial glimpse of it, they thought the whole foot had been sheared off at the ankle. The chief leg bones below my right knee, the tibia and the fibula, were broken into five pieces. The knee structure was more or less intact, but my right femur, or thigh bone, was broken twice, and the ball joint that connected it to my hip was damaged. Four ribs on my right side had snapped and their sharp ends had driven through the tissue of my lungs, lacerating them and causing pneumothorax, a deflation of the lungs and the dangerous escape of air into the chest cavity. My right collarbone and my sternum were broken. The once rigid frame of my chest had turned wobbly, its structural integrity gone, like a crushed birdcage. My right arm was a wreck—the elbow joint had taken some of the direct impact, and its bones were now a mosaic of breakages. But I am left-handed, and the left arm was in better shape, except for the hand, which had been (in the expressive technical term used by doctors) “de-gloved,” stripped of its skin and much of the muscular structure around the thumb.

But I had been lucky. Almost all the damage was skeletal. The internal soft tissues, liver, spleen, heart, were undamaged, or at worst merely bruised and shocked. My brain was intact—although it wasn’t working very well—and the most important part of my bone structure, the spine, was untouched.

That was a near miracle. Spines go out of service all too easily. The merest hairline crack in the spine can turn a healthy, reasonably athletic man into a paralyzed cripple: this is what happened to poor Christopher Reeve, the former Superman, in a fall from a horse, and it eventually killed him. The idea of being what specialists laconically call a “high quad”—paraplegic from the neck down, unable even to write your own end by loading a shotgun and sticking its muzzle in your mouth—has always appalled me.

But I wasn’t thinking clearly enough to be afraid of that. What I was afraid of, and mortally, was burning to death. Some are afraid of heights, others of rats, or mad dogs, or of death by drowning. My especial terror is fire, and now I realized that my nostrils were full of the banal stench of gasoline. Somewhere in the Nissan a line had ruptured. I could not move. I could only wait. There seemed to be little point in praying; in any case, there is no entity I believe in enough to pray to. Samuel Johnson once said that the prospect of being hanged concentrates a man’s mind wonderfully. The prospect, extended over hours, of dying in a gasoline fireball does much the same. It dissolves your more commonplace troubles—money, divorce, the difficulty of writing—and shows you what you really want to use your life for.

At one point I saw Death. He was sitting at a desk, like a banker. He made no gesture, but he opened his mouth and I looked right down his throat, which distended to become a tunnel: the bocca d’inferno of old Christian art. He expected me to yield, to go in. This filled me with abhorrence, a hatred of nonbeing. Not fear, exactly: more like passionate revolt. In that moment I realized that there is nothing whatever outside of the life we have; that the “meaning of life” is nothing other than life itself, obstinately asserting itself against emptiness and nullity. Life was so powerful, so demanding, and in my concussion and delirium, even as my systems were shutting down, I wanted it so much. Whatever this was, it was nothing like the nice, uplifting kind of near-death experience that religious writers, particularly those of an American-style fundamentalist bent, like to effuse about. Perhaps the simple truth is that, near death, you have visions and hallucinations of what most preoccupies you in life. I am a skeptic to whom the idea that a benign God created us and watches over us is something between a fairy story and a bad joke. People of a religious bent, however, are apt under such conditions to see the familiar kitsch of near-death experience—the tunnel of white light with Jesus at the end, as featured in the uplifting accounts of a score of American Kmart mystics. Jesus must have been busy with them when my time came: he didn’t show. There was, as far as I could tell, absolutely nothing on the other side.

So I was stuck; unable to move, and no more than intermittently conscious. Later, Kelly would testify that despite the injury to his leg he was able to make his way to my car and ask me what had happened; that I asked him the same question, and said, “I’m sorry, mate, I’m terribly sorry, I’m not sure if I fell asleep.” It has always been my habit to apologize first and ask questions later, and Sgt. Matt Turner, the Broome officer who was the first policeman at the scene, would later recount that I showed an almost silly degree of courtesy as rescue workers tried to extract me from the wreck, apologizing again and again for the inconvenience I was causing him and them.

It would be some hours before these rescuers got to the crash site. The person who set the machinery of rescue going had already been there. He was a middle-aged Aborigine named, rather fittingly, Joe Fishhook. He and his family lived nearby, at an Aboriginal settlement not far from Eco Beach named Bidyadanga. He was driving south in his truck, with his wife, Angie Wilridge, and their teenage daughter Ruth, along with a few members of their extended family, when the Commodore overtook them, zooming past at what he guessed to be about a hundred miles an hour. (Later, a police observer at the scene of the crash looked at the speedometer of the Commodore and saw that the needle was stuck by the collision impact at 150 k.p.h., about 90 m.p.h.)

Shortly afterward Fishhook came upon the wreck and saw the remains of my Pulsar straddling the center line of the highway. He stopped, got out, and tried but failed to free me from the wreck. I was crushed into it, like a sardine in a can squashed by a hammer. Fishhook gingerly checked that I was still breathing, but he couldn’t find any document that identified me. He checked the back of the Pulsar—the hatch door, at least, opened—and looked inside the cooler, finding the little tuna. Something snagged his attention. The fish was fresh, newly caught, but there was no tackle in the car. So I must have been fishing with someone else’s gear. That meant a professional guide. And how many such pros were there on this stretch of coast? Only one that Fishhook knew of—Danny O’Sullivan, a few kilometers away at Eco Beach, which was also where the nearest phone was.

After this excellent deduction, leaving his wife and daughter at the wreck, Fishhook spun a U-turn and drove back to the Eco turnoff. Twenty minutes later, burning red gravel all the way, he found Danny in the resort bar. Did he have a client who was taking a little bluefin home to Broome? Sure, said Danny: my mate Bob Hughes. Well, said Joey Fishhook equably, you better get up the road quick smart: he’s wrecked on the highway, he’s in deep shit, your mate is.

Danny rang the Broome police. He rang the Broome hospital. He sprinted downstairs, with Joey Fishhook close behind him. The two men took off in their cars, Danny accompanied by a former ambulance officer who now worked at the Eco Beach resort, Lorraine Lee. When the heat is on, Danny has a foot on the accelerator heavier than a rhino’s, and he reached the crash site in almost no time at all, by 6:45 p.m. He checked me out. I was as white as dirty skim milk and my breathing was shallow; I was sliding into a coma. “Bob, Bob mate, come on, bastard, wake up.” I could hear him, but he seemed very far away, as though we were in mutually distant rooms of a large, echoing house.

Lorraine Lee had brought some towels, with which she stanched the flow of blood from my head and left hand. I kept straining to hear Danny, but the effort was frustrated by waves of pain from my collarbone. Danny has a hand tough enough to strangle a crocodile. Fishing with him in the past, I have seen him reach lightning fast into a small line of breaking water and seize a passing shovelnose shark by the tail, hoicking it out of the wave with a feral grin of pleasure. Unfortunately, he now had my shoulder in a vise-like grip. It was meant to be comradely and reassuring, but he was squeezing broken bone. “You’re going to be fine, mate,” he was saying encouragingly. The pain was taking me over. “Oh Danny,” I whined, “it hurts, it hurts so much, it’s really bad, make it stop.” He kept squeezing the broken bone, sending bolts of fresh anguish through me. “She’ll be right, cobber,” he said. “She’s going to be right as rain. Just hang in there.” Squeeze from him, squawk from me. It took a few minutes to get cause and effect straightened out.

Then something passed between us that may never have happened; I am still not sure. I kept passing out and waking woozily up, and whenever I surfaced into consciousness I could still smell the petrol, that sickly smell building up to finish me off with one spark. I didn’t want to die at all, but most of all I didn’t want to die that way. I thought Danny owned a .38, and I implored him to finish me off if the car blew. “Just kill me,” I kept saying, or thought I did. “Just take me out, one shot, you know what to do.” And he, I think, swore that he would. But I do not know, and, looking back on it, I realize that I had asked the morally impossible of my friend, so perhaps I had never really asked it at all. I don’t know, and on a very deep level I remain uncertain and afraid to ask. But the desire to die before I could burn was very strong.

The absurdity made me sick. I thought of dying without ever seeing my sweetheart Doris again, never feeling that silky skin or hearing that soft voice in my ear. I had been through so many erotic miseries and matrimonial weirdnesses to reach Doris, the first woman ever to make me completely happy—and now it seemed that I would never revisit the paradise of the senses and the ecstasy of mutual trust to which she had granted me access. Instead there would be the opposite of paradise. It wasn’t dying as such that I feared, but dying in a hot blast, the air sucked out of my lungs, strangling on flame inside an uprushing column of unbearable heat: everything the Jesuits had told me about the crackling and eternal terrors of Hell now came back, across a chasm of fifty years. I could envision this. It would look like one of the Limbourg brothers’ illustrations to the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry—the picture of Satan bound down on a fiery grid, exhaling a spiral of helpless little burned souls into the air.

But the fire didn’t come. Neither did the fire brigade, nor the police, nor an ambulance. Some passing traffic stopped, including a semitrailer truck. Quite an array of vehicles was beginning to build up to the north and south of my Nissan, and these included some cars and four-wheel-drive pick- ups (known in Australia as “utes,” short for “utility vehicles”) driven by Aborigines. It being Friday night, there was meant to be a dance at the Bidyadanga settlement, and by twos and threes a curious group of Aborigines began to accumulate by the wreck.

They were behind me, so I couldn’t see them. I could hear them, though: a thin chanting, to the beat of handclaps, to which I could attach no meaning. Later I was told that the Aborigines had assembled in a half-circle behind my car, and were trying to sing me back to life. It must have seemed unlikely that they would succeed, but one person who was convinced they would was Joey Fishhook’s teenage daughter. She later said she saw what she stubbornly insisted was a spirit-apparition, not far from the Nissan. It was of no particular color. It looked in all respects human, except that it moved through the bush soundlessly, with a sort of elusive lightness.

This creature, or entity, is known to Aborigines as a feather-foot. It is not easy to say what a feather-foot is, or what it does. It is definitely not an animal spirit. It is a native equivalent of the Greek manifestation of Hermes as an emissary of Hades, in his role as Hermes Psychopompos, the “guider of souls.” It is neither hostile nor friendly: it just turns up at the site of an impending or possible death, and passes judgment on the soul and its prospects of survival in further incarnations. I didn’t see it, of course; even if it had been there, my vision was too blurred to see anything quick moving, and I couldn’t turn my head. But I like to think that perhaps it was a feather-foot, and that it had not found me altogether unacceptable.

Whether it could boast a real feather-foot or not, the Bidyadanga settlement did have its own nurse, a Filipina Catholic religious sister named Juliana Custodio. As soon as word about the collision reached her at Bidyadanga, she drove to the site to see if there was anything she could do. In the event, there wasn’t much. She found me, according to the police report, “trapped in the car, awake and talking, asking about his fish, swearing with the pain and then apologizing. Juliana said, ‘He was such a gentleman!’ She saw that his hip and chest bones were out of alignment . . . he was sweating and cold but his heart and pulse rate were very strong and his blood pressure normal.”

Sister Juliana did her best to get a saline IV into one of my veins, but they had collapsed. She wiped off the worst of the blood and applied some dressings to my head wounds. I kept sliding into patches of insensibility and she struggled to keep me awake, not with drugs, but simply by talking to me. Our conversation can’t have kept my wandering attention, because I soon gave up on it and started, as I was told later, to count aloud, backward from a hundred, one number slurring into the next—“forry-five, forry-four, forry-three . . .” Then I would lose track and have to start again, at a hundred. I thought I was trying to stay conscious, but Sister Juliana thought I was counting off my last moments; bystanders saw this good and devoted woman weeping with pity and frustration. Maybe we were both right. Later she would ask the Catholic priest at Bidyadanga, Father Patrick da Silva, to say a Mass for my recovery. “Juliana rang the hospital in Perth a few times during his stay,” the police report concludes, “and followed his progress with interest. She kept saying, ‘He was such a gentleman!’ ”

Meanwhile, a sea fog had rolled in from the Indian Ocean, slowing the sparse traffic to a crawl. Cars on the Great Northern Highway couldn’t make more than 60 k.p.h. (40 m.p.h.). It must have been two hours after the crash, close to nine o’clock, when a rescue team of volunteers from the Broome Fire Brigade at last reached the spot. Its men tugged and twisted at the door, but it would hardly budge. Eventually, they brought out the drastic solution to crushed car bodies—the so-called Jaws of Life, a massive pair of shears powered by hydraulic pressure. I was only dimly aware of this tool as it chomped through the Pulsar; I felt apprehensive but curiously distant as its blades groaned against the metal. Would they slip and chew my leg off? I didn’t much care; all I wanted was to be out of the danger of fire, away from the reek of gasoline. I was vaguely aware of skilled hands wiggling the lower parts of my legs, working them free. I felt, rather than heard, a resonant crunch deep down in my frame, at some level of my skeleton that had never been disturbed before, like the deep crack of an extracted tooth breaking free from the jawbone, as the shears bit off the spokes of the steering wheel whose rim was crushed into my thorax. The wheel was lifted free; one of the firemen tossed it in the back of the car, where I would find it nearly a year later. My whole chest felt light and empty now that the pressure was off. There was surprisingly little pain in it: this was due to shock, of course. Concerned faces were all around me. “I’m sorry about this,” I kept babbling. “I’m sorry to be so much trouble.” “You’ll be right, mate,” one of the firemen kept saying. “We’ll have you out of this in two ticks.” And they did, to my eternal gratitude. I felt a delirious sensation of lightness as I was lifted clear of the car. They slid a stretcher under me. My head felt swollen on its feeble stalk of a neck, lolling like a melon. Was my neck broken? I couldn’t frame the words of the question. At least I knew I could see and feel, and was alive. Luminescence was all around me: flashing, stuttering lights, red and orange punctuated by magnesium flashes, burning in haloes through the fog. In their intermittent flare I saw the face of Danny O’Sullivan, bending over me. His mouth turned down hideously—no, it was upside down, so he must be smiling.

“You’d have to be the toughest old bastard I know, cobber,” he said encouragingly.

Oh no, Danny, I wanted to say; you know dozens of guys who are tougher than me; dear God, I’m old and fat and I’m not going to last it through. “No, no, bullshit,” I managed to croak.

Danny reflected for a moment. “Ah well,” he conceded, “you’d have to be the toughest old art critic, anyway.”

That’ll do for me, I thought, and promptly swooned, like some crinolined Virginian lady in a novel. The stretcher locked onto its rails in the ambulance; it slid in with a clunk, the door slammed, and the medicos bent over me. I would not wake up for several weeks.

The first doctor to reach me from Broome had been Dr. Barbara Jarad, who was on call for the Aboriginal Medical Services at the Broome hospital that night. She had set off with the police in what she laughingly called “a high-speed pursuit vehicle”—creeping along, because of the fog, at 60 k.p.h. (40 m.p.h.). She talked on the police radio with Sister Juliana, who said she’d had difficulty getting a needle into me to administer saline. My veins are weak and recessive; under shock, they become almost impossible to find, rolling away from the needle. In the ambulance, Dr. Jarad got a saline needle in my arm, but on the road it ceased to work long before we reached the Broome hospital; I wasn’t tied down properly and the rolling of my body and the jolts of the vehicle kept pulling the needle out of the vein. I kept talking, not very lucidly; I gave the doctor my name and a few other details, but told her I had been born in 1995. It’s normal procedure to keep a trauma patient talking if you can, so that you can easily tell if he passes out. At the hospital the medical head, Dr. Tony Franklin, got another saline feed in my other arm, and Dr. Jarad did what she called a cut-down on my left, intact ankle, opening up the skin and flesh with a scalpel to expose a vein; not the easiest of maneuvers with a fleshy, overweight subject like myself.

It was now somewhat past midnight, almost six hours since the crash. The Broome hospital had been on the radio to the Flying Doctor Service. It could fly me more than 1,000 miles south to Perth, the capital of Western Australia, which had a bigger hospital than Broome’s—one that included an Intensive Care Unit.

And intensive care was what I was going to need. The doctors in Perth had me on the operating table for thirteen hours straight and, I was told much later, they nearly lost me several times. Their work was extraordinary. All the odds, I take it, were against my survival, and without these doctors and the immense devotion and skill of their work I could not possibly have survived. I ended up in semi-stable condition, with tubes running in and out of me, and a ventilator doing my breathing.

I was in intensive care for five weeks, in a semiconscious delirium, while the doctors and nurses of Royal Perth Hospital labored to put me together and bring me back, detail by detail, to life. I don’t know that I’d recommend to the unwary foreigner that he or she ought to live in West Australia. But I do know that, if one has the misfortune to undergo a near-fatal car smash, West Australia—and, specifically, the Royal Perth Hospital—is an extremely good place to be.

And then he knew no more.” It was the standard exit from an action paragraph in the books of my childhood: Bulldog Drummond is sapped on the back of the head, Hero X falls through a trapdoor, Macho Y realizes, all too late, that the tea he has sipped in the villain’s Shanghai parlor contained a powerful drug. The room spins, consciousness goes. We wake (if we are lucky) remembering nothing. Not an erasure, in which the traces of an earlier design may, however vaguely, be discerned. Instead, a whiteout.

If only.

The word “coma,” if my experience is any guide, covers a host of states that slide into one another unpredictably.

If “coma” means the cessation of awareness or internal consciousness—the black hole, the blank wall—then I wasn’t in a coma for those five and a half weeks in the Intensive Care Unit of Royal Perth.

On the contrary: at least some of the time I was living with (literally) fantastic intensity, my mind pervaded by narrative phantasms of extreme clarity and unshakeable, Daliesque vividness. But I couldn’t communicate them to the outside world, or to anyone in it, including the doctors, the nurses, and my worried and puzzled friends. I was sealed off, boiling with hallucination.

I don’t remember feeling frustrated by this: in some way I knew that even if I had been able to describe these states and narratives, these loved ones could not have understood their import. It would have taken too much explaining. This, you might say, was my unconscious mind being smart, saving its energies as best it could. To explain the details, to show by what twisting, metaphor-ridden paths they led back to core experiences whose nature was barely evident even to me, would have been a hopeless task; I lay in the middle of these narratives like a man who has cut the binding strings on a coil of fencing wire which, springing anarchically from confinement, now has him in its tangled embrace. These dreams were tenacious. Normally I dream in a fairly episodic way, and the thread easily gets lost. But in the coma, I had the frightening sensation of being lost in an exceptionally, crazily vivid parallel life, one that had cross-connections to my own but which could not be set aside—because, I realized later, I was close to death and could not get a grip on any reality that could pull me out of hallucination. I was not aware that I was not alone: my fantasies were too thickly peopled to let in real people who were close to me.

From the Hardcover edition.

A Bloody Expat

The most extreme change in my life occurred, out of a blue sky, on the 30th of May, 1999, a little short of my sixty-first birthday.

I was in Western Australia, where I had been making a TV series about my native country. I had taken a couple of days off, and chosen to spend them fishing off the shore of a resort named Eco Beach with a friend, Danny O’Sullivan, a professional guide. We went after small offshore tuna, with fly rods, in an open skiff. It had been a wonderful day: fish breaking everywhere, fighting fiercely when hooked, and one—a small bluefin, about twenty pounds—kept to be eaten later with the crew in Broome.

Now, after a nap, I was on my way back to the Northern Highway, which parallels the huge flat biscuit of a coast where the desert breaks off into the Indian Ocean.

After about ten kilometers, the red dirt road from Eco Beach ended in a cattle gate. I stopped short of it, got out of the car, unhooked the latching chain, swung the gate open. I got back in the car, drove through, stopped again, got out, and closed the gate behind me. Then I hopped back in the car again and drove out onto the tar and concrete of the Great Northern Highway, cautiously looking both ways in the bright, almost horizontal evening light. No road trains galloping toward me: nothing except emptiness. I turned left, heading north for Broome, on the left side of the road, as people have in Australia ever since 1815, when its colonial governor, an autocratic laird named Lachlan Macquarie, decreed that Australians must henceforth ride and drive on the same side as people did in his native Scotland.

It was still daylight, but only just. I flipped my lights on.

There was no crash, no impact, no pain. It was as though nothing had happened. I just drove off the edge of the world, feeling nothing.

I do not know how fast I was going.

I am not a fast driver, or in any way a daring one. Driving has never been second nature to me. I am pawky, old-maidish, behind the wheel. But I collided, head-on, with another car, a Holden Commodore with two people in the front seat and one in the back. It was dusk, about 6:30 p.m. This was the first auto accident I ever had in my life, and I retain absolutely no memory of it. Try as I may, I can dredge nothing up, not even the memory of fear. The slate is wiped clean, as by a damp rag.

I was probably on the wrong (that is, the right-hand) side of the road, over the yellow line—though not very far over. I say “probably” because, at my trial a year later, the magistrate did not find that there was enough evidence to prove, beyond reasonable doubt, that I had been. The Commodore was coming on at some 90 m.p.h., possibly more. I was approaching it at about 50 m.p.h.. Things happen very quickly when two cars have a closing speed of more than 130 m.p.h. It only takes a second for them to get seventy feet closer to one another. No matter how hard you hit the brakes, there isn’t much you can do.

We plowed straight into one another, Commodore registered 7ex 954 into Nissan Pulsar registered 9 yr 650: two red cars in the desert, driver’s side to driver’s side, right headlamp to right headlamp. I have no memory of this. From the moment of impact for weeks to come, I would have no short-term memory of anything. All I know about the actual collision, until after almost a year, when I saw the remains of my rented car in a junkyard in Broome, is what I was told by others.

The other car spun off the highway, skidded down a shallow dirt slope, and ended up half-hidden in the low desert scrub. Its three occupants were injured, two not seriously. Darren William Kelly, thirty-two, the driver, had just come off a stint working on a fishing boat and was heading south to Port Hedland to find any work he could get. He had a broken tibia. Colin Craig Bowe, thirty-six, a builder’s laborer, was riding in the front seat and sustained a broken ankle. Darryn George Bennett, twenty-four, had been working as a deckhand on the same boat as Kelly, the True Blue. Kelly and Bowe were mates; they had known each other for two years. Neither had known Bennett before. He had heard they were driving south to Port Hedland, and he asked for a ride. He was a young itinerant worker in his midtwenties, whose main skill was bricklaying.

Their encounter with the world of writing only added to their misfortunes. All three were addicts and part-time drug dealers. At the moment of the crash, Bennett, in the backseat, was rolling a “cone” of marijuana, a joint. It may or may not have been the first one to be smoked on what was meant to be a thousand-kilometer drive south.

In any case, they had things in common. They had all done jail time. They were young working-class men living now on that side of the law, now on this: sometimes feral, sometimes bewildered, seldom knowing what the next month, let alone the next birthday, would bring.

Not long after he had recovered from the injuries of the collision, Bennett tried to tear the face off an enemy in a bar with a broken bottle. Bowe, as soon as his injuries had healed, attempted an armed robbery, but was arrested, tried, and sentenced to ten years in jail.

Bennett was by far the worst hurt of the three. The impact catapulted him forward against the restraint of the seat belt and gave him a perforated bowel. He had no skeletal damage. All three of them were able to struggle out of the wreck of the Commodore, which had not rolled over. The effort of doing so was agonizing for Bennett, who collapsed on the verge of the road, his guts flooded with pain.

If the Commodore was badly smashed up, my Nissan Pulsar was an inchoate mass of red metal and broken glass, barely recognizable as having once been a car. When at last I saw it in Broome on the eve of my trial, eleven months later, I couldn’t see how a cockroach could have survived that wreck, let alone a human being.

The car had telescoped. The driver’s seat had slammed forward, pinning me against the steering wheel, which was twisted out of shape by the impact of my body, nearly impaling me on the steering column. Much of the driver’s side of the Pulsar’s body had been ripped away, whether by the initial impact or, later, by the hydraulic tools used by the fire brigade and ambulance crew in their long struggle to free me from the wreckage. It looked like a half-car. It was as though the fat, giant foot of God from the old Monty Python graphics had stamped on it and ground it into the concrete. Later, I would make derogatory noises about “that piece of Jap shit” I’d been driving. I was wrong, of course. The damage had saved my life: the gradual collapse and telescoping of the Nissan’s body, compressed into milliseconds, had absorbed and dissipated far more of the impact energy than a more rigid frame could have done.

Now it was folded around me like crude origami. I could scarcely move a finger. Trapped, intermittently conscious, deep in shock and bloodier than Banquo, I had only the vaguest notion of what had happened to me. Whatever it might have been, it was far beyond my experience. I did not recognize my own injuries, and had no idea how bad they were. As it turned out, they were bad enough. Under extreme impact, bones may not break neatly. They can explode into fragments, like a cookie hit by a hammer, and that’s what happened to several of mine.

The catalog of trauma turned out to be long. Most of it was concentrated on the right-hand side of my body—the side that bore the brunt of the collision. As the front of the Nissan collapsed, my right foot was forced through the floor and doubled underneath me; hours later, when my rescuers were at last able to get a partial glimpse of it, they thought the whole foot had been sheared off at the ankle. The chief leg bones below my right knee, the tibia and the fibula, were broken into five pieces. The knee structure was more or less intact, but my right femur, or thigh bone, was broken twice, and the ball joint that connected it to my hip was damaged. Four ribs on my right side had snapped and their sharp ends had driven through the tissue of my lungs, lacerating them and causing pneumothorax, a deflation of the lungs and the dangerous escape of air into the chest cavity. My right collarbone and my sternum were broken. The once rigid frame of my chest had turned wobbly, its structural integrity gone, like a crushed birdcage. My right arm was a wreck—the elbow joint had taken some of the direct impact, and its bones were now a mosaic of breakages. But I am left-handed, and the left arm was in better shape, except for the hand, which had been (in the expressive technical term used by doctors) “de-gloved,” stripped of its skin and much of the muscular structure around the thumb.

But I had been lucky. Almost all the damage was skeletal. The internal soft tissues, liver, spleen, heart, were undamaged, or at worst merely bruised and shocked. My brain was intact—although it wasn’t working very well—and the most important part of my bone structure, the spine, was untouched.

That was a near miracle. Spines go out of service all too easily. The merest hairline crack in the spine can turn a healthy, reasonably athletic man into a paralyzed cripple: this is what happened to poor Christopher Reeve, the former Superman, in a fall from a horse, and it eventually killed him. The idea of being what specialists laconically call a “high quad”—paraplegic from the neck down, unable even to write your own end by loading a shotgun and sticking its muzzle in your mouth—has always appalled me.

But I wasn’t thinking clearly enough to be afraid of that. What I was afraid of, and mortally, was burning to death. Some are afraid of heights, others of rats, or mad dogs, or of death by drowning. My especial terror is fire, and now I realized that my nostrils were full of the banal stench of gasoline. Somewhere in the Nissan a line had ruptured. I could not move. I could only wait. There seemed to be little point in praying; in any case, there is no entity I believe in enough to pray to. Samuel Johnson once said that the prospect of being hanged concentrates a man’s mind wonderfully. The prospect, extended over hours, of dying in a gasoline fireball does much the same. It dissolves your more commonplace troubles—money, divorce, the difficulty of writing—and shows you what you really want to use your life for.

At one point I saw Death. He was sitting at a desk, like a banker. He made no gesture, but he opened his mouth and I looked right down his throat, which distended to become a tunnel: the bocca d’inferno of old Christian art. He expected me to yield, to go in. This filled me with abhorrence, a hatred of nonbeing. Not fear, exactly: more like passionate revolt. In that moment I realized that there is nothing whatever outside of the life we have; that the “meaning of life” is nothing other than life itself, obstinately asserting itself against emptiness and nullity. Life was so powerful, so demanding, and in my concussion and delirium, even as my systems were shutting down, I wanted it so much. Whatever this was, it was nothing like the nice, uplifting kind of near-death experience that religious writers, particularly those of an American-style fundamentalist bent, like to effuse about. Perhaps the simple truth is that, near death, you have visions and hallucinations of what most preoccupies you in life. I am a skeptic to whom the idea that a benign God created us and watches over us is something between a fairy story and a bad joke. People of a religious bent, however, are apt under such conditions to see the familiar kitsch of near-death experience—the tunnel of white light with Jesus at the end, as featured in the uplifting accounts of a score of American Kmart mystics. Jesus must have been busy with them when my time came: he didn’t show. There was, as far as I could tell, absolutely nothing on the other side.

So I was stuck; unable to move, and no more than intermittently conscious. Later, Kelly would testify that despite the injury to his leg he was able to make his way to my car and ask me what had happened; that I asked him the same question, and said, “I’m sorry, mate, I’m terribly sorry, I’m not sure if I fell asleep.” It has always been my habit to apologize first and ask questions later, and Sgt. Matt Turner, the Broome officer who was the first policeman at the scene, would later recount that I showed an almost silly degree of courtesy as rescue workers tried to extract me from the wreck, apologizing again and again for the inconvenience I was causing him and them.

It would be some hours before these rescuers got to the crash site. The person who set the machinery of rescue going had already been there. He was a middle-aged Aborigine named, rather fittingly, Joe Fishhook. He and his family lived nearby, at an Aboriginal settlement not far from Eco Beach named Bidyadanga. He was driving south in his truck, with his wife, Angie Wilridge, and their teenage daughter Ruth, along with a few members of their extended family, when the Commodore overtook them, zooming past at what he guessed to be about a hundred miles an hour. (Later, a police observer at the scene of the crash looked at the speedometer of the Commodore and saw that the needle was stuck by the collision impact at 150 k.p.h., about 90 m.p.h.)

Shortly afterward Fishhook came upon the wreck and saw the remains of my Pulsar straddling the center line of the highway. He stopped, got out, and tried but failed to free me from the wreck. I was crushed into it, like a sardine in a can squashed by a hammer. Fishhook gingerly checked that I was still breathing, but he couldn’t find any document that identified me. He checked the back of the Pulsar—the hatch door, at least, opened—and looked inside the cooler, finding the little tuna. Something snagged his attention. The fish was fresh, newly caught, but there was no tackle in the car. So I must have been fishing with someone else’s gear. That meant a professional guide. And how many such pros were there on this stretch of coast? Only one that Fishhook knew of—Danny O’Sullivan, a few kilometers away at Eco Beach, which was also where the nearest phone was.

After this excellent deduction, leaving his wife and daughter at the wreck, Fishhook spun a U-turn and drove back to the Eco turnoff. Twenty minutes later, burning red gravel all the way, he found Danny in the resort bar. Did he have a client who was taking a little bluefin home to Broome? Sure, said Danny: my mate Bob Hughes. Well, said Joey Fishhook equably, you better get up the road quick smart: he’s wrecked on the highway, he’s in deep shit, your mate is.

Danny rang the Broome police. He rang the Broome hospital. He sprinted downstairs, with Joey Fishhook close behind him. The two men took off in their cars, Danny accompanied by a former ambulance officer who now worked at the Eco Beach resort, Lorraine Lee. When the heat is on, Danny has a foot on the accelerator heavier than a rhino’s, and he reached the crash site in almost no time at all, by 6:45 p.m. He checked me out. I was as white as dirty skim milk and my breathing was shallow; I was sliding into a coma. “Bob, Bob mate, come on, bastard, wake up.” I could hear him, but he seemed very far away, as though we were in mutually distant rooms of a large, echoing house.

Lorraine Lee had brought some towels, with which she stanched the flow of blood from my head and left hand. I kept straining to hear Danny, but the effort was frustrated by waves of pain from my collarbone. Danny has a hand tough enough to strangle a crocodile. Fishing with him in the past, I have seen him reach lightning fast into a small line of breaking water and seize a passing shovelnose shark by the tail, hoicking it out of the wave with a feral grin of pleasure. Unfortunately, he now had my shoulder in a vise-like grip. It was meant to be comradely and reassuring, but he was squeezing broken bone. “You’re going to be fine, mate,” he was saying encouragingly. The pain was taking me over. “Oh Danny,” I whined, “it hurts, it hurts so much, it’s really bad, make it stop.” He kept squeezing the broken bone, sending bolts of fresh anguish through me. “She’ll be right, cobber,” he said. “She’s going to be right as rain. Just hang in there.” Squeeze from him, squawk from me. It took a few minutes to get cause and effect straightened out.

Then something passed between us that may never have happened; I am still not sure. I kept passing out and waking woozily up, and whenever I surfaced into consciousness I could still smell the petrol, that sickly smell building up to finish me off with one spark. I didn’t want to die at all, but most of all I didn’t want to die that way. I thought Danny owned a .38, and I implored him to finish me off if the car blew. “Just kill me,” I kept saying, or thought I did. “Just take me out, one shot, you know what to do.” And he, I think, swore that he would. But I do not know, and, looking back on it, I realize that I had asked the morally impossible of my friend, so perhaps I had never really asked it at all. I don’t know, and on a very deep level I remain uncertain and afraid to ask. But the desire to die before I could burn was very strong.

The absurdity made me sick. I thought of dying without ever seeing my sweetheart Doris again, never feeling that silky skin or hearing that soft voice in my ear. I had been through so many erotic miseries and matrimonial weirdnesses to reach Doris, the first woman ever to make me completely happy—and now it seemed that I would never revisit the paradise of the senses and the ecstasy of mutual trust to which she had granted me access. Instead there would be the opposite of paradise. It wasn’t dying as such that I feared, but dying in a hot blast, the air sucked out of my lungs, strangling on flame inside an uprushing column of unbearable heat: everything the Jesuits had told me about the crackling and eternal terrors of Hell now came back, across a chasm of fifty years. I could envision this. It would look like one of the Limbourg brothers’ illustrations to the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry—the picture of Satan bound down on a fiery grid, exhaling a spiral of helpless little burned souls into the air.

But the fire didn’t come. Neither did the fire brigade, nor the police, nor an ambulance. Some passing traffic stopped, including a semitrailer truck. Quite an array of vehicles was beginning to build up to the north and south of my Nissan, and these included some cars and four-wheel-drive pick- ups (known in Australia as “utes,” short for “utility vehicles”) driven by Aborigines. It being Friday night, there was meant to be a dance at the Bidyadanga settlement, and by twos and threes a curious group of Aborigines began to accumulate by the wreck.

They were behind me, so I couldn’t see them. I could hear them, though: a thin chanting, to the beat of handclaps, to which I could attach no meaning. Later I was told that the Aborigines had assembled in a half-circle behind my car, and were trying to sing me back to life. It must have seemed unlikely that they would succeed, but one person who was convinced they would was Joey Fishhook’s teenage daughter. She later said she saw what she stubbornly insisted was a spirit-apparition, not far from the Nissan. It was of no particular color. It looked in all respects human, except that it moved through the bush soundlessly, with a sort of elusive lightness.

This creature, or entity, is known to Aborigines as a feather-foot. It is not easy to say what a feather-foot is, or what it does. It is definitely not an animal spirit. It is a native equivalent of the Greek manifestation of Hermes as an emissary of Hades, in his role as Hermes Psychopompos, the “guider of souls.” It is neither hostile nor friendly: it just turns up at the site of an impending or possible death, and passes judgment on the soul and its prospects of survival in further incarnations. I didn’t see it, of course; even if it had been there, my vision was too blurred to see anything quick moving, and I couldn’t turn my head. But I like to think that perhaps it was a feather-foot, and that it had not found me altogether unacceptable.

Whether it could boast a real feather-foot or not, the Bidyadanga settlement did have its own nurse, a Filipina Catholic religious sister named Juliana Custodio. As soon as word about the collision reached her at Bidyadanga, she drove to the site to see if there was anything she could do. In the event, there wasn’t much. She found me, according to the police report, “trapped in the car, awake and talking, asking about his fish, swearing with the pain and then apologizing. Juliana said, ‘He was such a gentleman!’ She saw that his hip and chest bones were out of alignment . . . he was sweating and cold but his heart and pulse rate were very strong and his blood pressure normal.”

Sister Juliana did her best to get a saline IV into one of my veins, but they had collapsed. She wiped off the worst of the blood and applied some dressings to my head wounds. I kept sliding into patches of insensibility and she struggled to keep me awake, not with drugs, but simply by talking to me. Our conversation can’t have kept my wandering attention, because I soon gave up on it and started, as I was told later, to count aloud, backward from a hundred, one number slurring into the next—“forry-five, forry-four, forry-three . . .” Then I would lose track and have to start again, at a hundred. I thought I was trying to stay conscious, but Sister Juliana thought I was counting off my last moments; bystanders saw this good and devoted woman weeping with pity and frustration. Maybe we were both right. Later she would ask the Catholic priest at Bidyadanga, Father Patrick da Silva, to say a Mass for my recovery. “Juliana rang the hospital in Perth a few times during his stay,” the police report concludes, “and followed his progress with interest. She kept saying, ‘He was such a gentleman!’ ”

Meanwhile, a sea fog had rolled in from the Indian Ocean, slowing the sparse traffic to a crawl. Cars on the Great Northern Highway couldn’t make more than 60 k.p.h. (40 m.p.h.). It must have been two hours after the crash, close to nine o’clock, when a rescue team of volunteers from the Broome Fire Brigade at last reached the spot. Its men tugged and twisted at the door, but it would hardly budge. Eventually, they brought out the drastic solution to crushed car bodies—the so-called Jaws of Life, a massive pair of shears powered by hydraulic pressure. I was only dimly aware of this tool as it chomped through the Pulsar; I felt apprehensive but curiously distant as its blades groaned against the metal. Would they slip and chew my leg off? I didn’t much care; all I wanted was to be out of the danger of fire, away from the reek of gasoline. I was vaguely aware of skilled hands wiggling the lower parts of my legs, working them free. I felt, rather than heard, a resonant crunch deep down in my frame, at some level of my skeleton that had never been disturbed before, like the deep crack of an extracted tooth breaking free from the jawbone, as the shears bit off the spokes of the steering wheel whose rim was crushed into my thorax. The wheel was lifted free; one of the firemen tossed it in the back of the car, where I would find it nearly a year later. My whole chest felt light and empty now that the pressure was off. There was surprisingly little pain in it: this was due to shock, of course. Concerned faces were all around me. “I’m sorry about this,” I kept babbling. “I’m sorry to be so much trouble.” “You’ll be right, mate,” one of the firemen kept saying. “We’ll have you out of this in two ticks.” And they did, to my eternal gratitude. I felt a delirious sensation of lightness as I was lifted clear of the car. They slid a stretcher under me. My head felt swollen on its feeble stalk of a neck, lolling like a melon. Was my neck broken? I couldn’t frame the words of the question. At least I knew I could see and feel, and was alive. Luminescence was all around me: flashing, stuttering lights, red and orange punctuated by magnesium flashes, burning in haloes through the fog. In their intermittent flare I saw the face of Danny O’Sullivan, bending over me. His mouth turned down hideously—no, it was upside down, so he must be smiling.

“You’d have to be the toughest old bastard I know, cobber,” he said encouragingly.

Oh no, Danny, I wanted to say; you know dozens of guys who are tougher than me; dear God, I’m old and fat and I’m not going to last it through. “No, no, bullshit,” I managed to croak.

Danny reflected for a moment. “Ah well,” he conceded, “you’d have to be the toughest old art critic, anyway.”

That’ll do for me, I thought, and promptly swooned, like some crinolined Virginian lady in a novel. The stretcher locked onto its rails in the ambulance; it slid in with a clunk, the door slammed, and the medicos bent over me. I would not wake up for several weeks.

The first doctor to reach me from Broome had been Dr. Barbara Jarad, who was on call for the Aboriginal Medical Services at the Broome hospital that night. She had set off with the police in what she laughingly called “a high-speed pursuit vehicle”—creeping along, because of the fog, at 60 k.p.h. (40 m.p.h.). She talked on the police radio with Sister Juliana, who said she’d had difficulty getting a needle into me to administer saline. My veins are weak and recessive; under shock, they become almost impossible to find, rolling away from the needle. In the ambulance, Dr. Jarad got a saline needle in my arm, but on the road it ceased to work long before we reached the Broome hospital; I wasn’t tied down properly and the rolling of my body and the jolts of the vehicle kept pulling the needle out of the vein. I kept talking, not very lucidly; I gave the doctor my name and a few other details, but told her I had been born in 1995. It’s normal procedure to keep a trauma patient talking if you can, so that you can easily tell if he passes out. At the hospital the medical head, Dr. Tony Franklin, got another saline feed in my other arm, and Dr. Jarad did what she called a cut-down on my left, intact ankle, opening up the skin and flesh with a scalpel to expose a vein; not the easiest of maneuvers with a fleshy, overweight subject like myself.

It was now somewhat past midnight, almost six hours since the crash. The Broome hospital had been on the radio to the Flying Doctor Service. It could fly me more than 1,000 miles south to Perth, the capital of Western Australia, which had a bigger hospital than Broome’s—one that included an Intensive Care Unit.

And intensive care was what I was going to need. The doctors in Perth had me on the operating table for thirteen hours straight and, I was told much later, they nearly lost me several times. Their work was extraordinary. All the odds, I take it, were against my survival, and without these doctors and the immense devotion and skill of their work I could not possibly have survived. I ended up in semi-stable condition, with tubes running in and out of me, and a ventilator doing my breathing.

I was in intensive care for five weeks, in a semiconscious delirium, while the doctors and nurses of Royal Perth Hospital labored to put me together and bring me back, detail by detail, to life. I don’t know that I’d recommend to the unwary foreigner that he or she ought to live in West Australia. But I do know that, if one has the misfortune to undergo a near-fatal car smash, West Australia—and, specifically, the Royal Perth Hospital—is an extremely good place to be.

And then he knew no more.” It was the standard exit from an action paragraph in the books of my childhood: Bulldog Drummond is sapped on the back of the head, Hero X falls through a trapdoor, Macho Y realizes, all too late, that the tea he has sipped in the villain’s Shanghai parlor contained a powerful drug. The room spins, consciousness goes. We wake (if we are lucky) remembering nothing. Not an erasure, in which the traces of an earlier design may, however vaguely, be discerned. Instead, a whiteout.

If only.

The word “coma,” if my experience is any guide, covers a host of states that slide into one another unpredictably.

If “coma” means the cessation of awareness or internal consciousness—the black hole, the blank wall—then I wasn’t in a coma for those five and a half weeks in the Intensive Care Unit of Royal Perth.

On the contrary: at least some of the time I was living with (literally) fantastic intensity, my mind pervaded by narrative phantasms of extreme clarity and unshakeable, Daliesque vividness. But I couldn’t communicate them to the outside world, or to anyone in it, including the doctors, the nurses, and my worried and puzzled friends. I was sealed off, boiling with hallucination.

I don’t remember feeling frustrated by this: in some way I knew that even if I had been able to describe these states and narratives, these loved ones could not have understood their import. It would have taken too much explaining. This, you might say, was my unconscious mind being smart, saving its energies as best it could. To explain the details, to show by what twisting, metaphor-ridden paths they led back to core experiences whose nature was barely evident even to me, would have been a hopeless task; I lay in the middle of these narratives like a man who has cut the binding strings on a coil of fencing wire which, springing anarchically from confinement, now has him in its tangled embrace. These dreams were tenacious. Normally I dream in a fairly episodic way, and the thread easily gets lost. But in the coma, I had the frightening sensation of being lost in an exceptionally, crazily vivid parallel life, one that had cross-connections to my own but which could not be set aside—because, I realized later, I was close to death and could not get a grip on any reality that could pull me out of hallucination. I was not aware that I was not alone: my fantasies were too thickly peopled to let in real people who were close to me.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Riveting. . . . Marvelously entertaining. . . . Hughes’ portraits of people he knew in his youth often display the bravura touch that has distinguished his best journalism.” —The New York Times“[Hughes] deftly intertwines personal and cultural history in this fiercely erudite memoir. . . . A fascinating examination of artistic patrimony and the formation of a critic.” —The New Yorker“Splendid. . . . Hughes has turned his hand to autobiography, with predictably and gratifyingly rewarding results.” —The Washington Post Book World“Hughes is the sort of ebullient writer who floods his reader with great bursting accumulations of words and gets carried away with the sheer exuberance of his narrative. It is compelling. You don’t want to miss a sentence” —The Christian Science Monitor