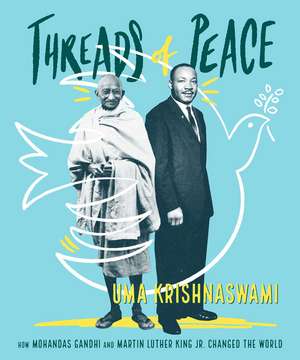

Threads of Peace: How Mohandas Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr. Changed the World

Autor Uma Krishnaswamien Limba Engleză Paperback – 28 sep 2022 – vârsta de la 9 ani

Mohandas Gandhi and Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. both shook and changed the world in their quest for peace among all people, but what threads connected these great activists together in their shared goal of social revolution?

A lawyer and activist, tiny of stature with giant ideas, in British-ruled India at the beginning of the 20th century.

A minister from Georgia with a thunderous voice and hopes for peace at the height of the civil rights movement in America.

Born more than a half-century apart, with seemingly little in common except one shared wish, both would go on to be icons of peaceful resistance and human decency. Both preached love for all human beings, regardless of race or religion. Both believed that freedom and justice were won by not one, but many. Both met their ends in the most unpeaceful of ways—assassination.

But what led them down the path of peace? How did their experiences parallel...and diverge? Threads of Peace keenly examines and celebrates these extraordinary activists’ lives, the threads that connect them, and the threads of peace they laid throughout the world, for us to pick up, and weave together.

Preț: 58.55 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 88

Preț estimativ în valută:

11.20€ • 11.63$ • 9.37£

11.20€ • 11.63$ • 9.37£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 22 februarie-08 martie

Livrare express 08-14 februarie pentru 45.47 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781481416795

ISBN-10: 1481416790

Pagini: 336

Ilustrații: f-c cvr (fx: spot gloss on matte)+4C int. ill.-photos; digital

Dimensiuni: 191 x 229 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.86 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Atheneum/Caitlyn Dlouhy Books

Colecția Atheneum/Caitlyn Dlouhy Books

ISBN-10: 1481416790

Pagini: 336

Ilustrații: f-c cvr (fx: spot gloss on matte)+4C int. ill.-photos; digital

Dimensiuni: 191 x 229 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.86 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Atheneum/Caitlyn Dlouhy Books

Colecția Atheneum/Caitlyn Dlouhy Books

Notă biografică

Uma Krishnaswami is the author of several books for children including The Grand Plan to Fix Everything and The Problem with Being Slightly Heroic. She was born in New Delhi, India, and now lives in British Columbia, Canada.

Extras

Chapter 1: A Place of Warm Breezes

PORBANDAR, INDIA: 1869

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi came into the world in a seaside town called Porbandar in the Kathiawar Peninsula of western India. It is a place of warm breezes. The land juts out into the Arabian Sea, its ear turned to the ocean and to the world beyond.

Once a bustling port, Porbandar was now a sleepy town on the water’s edge. Outside its borders, vast tracts of the Indian subcontinent lay under the rule of the British. Scattered in between were princely states, large and small, still ruled by Indian kings.

Some were kind rulers, others tyrannical. Some were independent in name. Most quaked at the power of the British Empire on their doorsteps. In turn, the British kept an eye on the Indian royals, to make sure that none of them gained any real strength.

The kingdom of Porbandar was too small to pose any threat to the British. It consisted of a single town, on a coastal strip less than twenty-five miles wide. Its creamy-white limestone buildings earned it the name of the “White City.”

Map of British India, 1867

The British in India

The British came as traders to India—and stayed.

The East India Company had been chartered in 1600 to buy and sell spices. Over the years, the company also traded in tea, indigo, salt, silk, cotton, and other goods—among them, vast quantities of the drug opium, sold to China. Soon the company built permanent offices and took over large areas of land.

By the mid-nineteenth century, the company ran much of the country. It collected taxes. It employed an army. It was the face of the British government in India, and it ruled harshly.

In 1857, twelve years before Gandhi’s birth, a rebellion by Indian soldiers in the company army had been brutally crushed by British commanders. The company was dissolved and its powers taken over by the British government. In 1876, Queen Victoria was crowned Empress of India. This was the beginning of the British rule that came to be called “the Raj.”

The Gandhi family home, a hundred years old, with twelve rooms and three floors, stood in a narrow lane. Its thick walls kept the interior cool even in the hottest summers. In some rooms, the walls were painted with floral and geometric designs. Evening breezes blew over the rooftop, where the children played.

The women of the household ran the kitchen—chopping vegetables with great curving knife-blades, grinding millet into flour, stirring pots of lentils and rice over crackling wood-fires. They slathered rounds of flat bread with ghee made from scalded butter. The fragrance of ground spices, homemade pickles, and chutneys wafted into the central courtyard.

Mohandas lived in this house with his father, Karamchand Gandhi (“Kaba” for short), and his mother, Putliba. Putliba was Kaba Gandhi’s fourth wife. The first two had died in childbirth, and the third was childless and ill. Kaba wanted a son, so he had asked and obtained his third wife’s permission to marry Putliba. His sick third wife, however, remained living with the family until her death. The white-walled house was also home to two daughters from Kaba’s earlier marriages, Mohandas’s half sisters, and of course to Putliba and Kaba’s other children—a daughter, Raliat, and two sons, Laxmidas and Karsandas.

Kaba’s Wives

Under the law, Kaba Gandhi didn’t need his wife’s permission to marry again. Hindu men in nineteenth-century India were allowed to have more than one wife at a time.

Mohandas’s mother, Putliba, and Mohandas’s father, Kaba Gandhi

Raliat loved the new baby. She played with Mohandas and carried him everywhere, hardly putting him down for a moment. As he grew to be a toddler, she said her little brother was “restless as mercury,” unable to “sit still even for a little while. He must be either playing or roaming about.” He was mischievous, too. When they went to the marketplace, he’d chase the neighborhood dogs and tweak their ears.

Kaba Gandhi’s father had been the diwan to the ruler of Porbandar. Kaba, who held the job of letter writer and clerk, inherited his father’s high office upon his death. As a token of the promotion, the ruler presented him with a silver inkstand and inkpot. Kaba could read and write in his native Gujarati language, although, like many Indians of the time, he knew no English.

diwan | (also dewan) noun In 19th century India, the chief minister or finance minister of a princely state

Kaba was preoccupied with his work and traveled often. When the fortunes of Porbandar’s ruler waned, he began to look for work in other local kingdoms. The new baby saw little of his father.

But the women of the house loved and indulged young Mohandas. Fondly, they called him “Monia.” They played with him and teased him. While cooking delicious vegetarian meals for the family, they took care to make special sweets for Mohandas. One of the household servants in particular, Rambha, doted on him. She became his loving nurse.

Mohandas adored his mother. She was gentle yet strong. Once, a poisonous scorpion got into the house and ran over her bare feet. Everyone panicked. Mohandas cowered. But his mother simply scooped the insect up and threw it out the window.

Mohandas at age seven

Scorpions were not the only things Mohandas feared. Even in the embrace of a loving family, he was timid and struck by frequent terrors. He was afraid of the dark and of ghosts, evil spirits, and demons. He was sure they waited for him around every dark corner or lurked in twilight shadows. His nurse, Rambha, tried her best to bolster his courage. She told him to repeat the name of Rama, the god-prince of Hindu mythology, so good and noble that chanting his name was said to drive away all evil.

“Rama, Rama!” The boy intoned the holy name over and over. It did no good. Come nightfall, he could not shake his fear.

Yet the same excitable imagination that stoked anxiety also drew him to the faith of his mother. Most Hindu families mainly worshipped one—or at most a few—of the many gods in the Hindu tradition. Putliba worshipped them all! She took her son to numerous temples in the area. She even took him to one where the walls were inscribed with writings from both Hindu scriptures and the Muslim holy book, the Quran. A shy boy paying attention to his mother’s words and actions, Mohandas likely absorbed some of her open-minded religious views.

“The outstanding impression my mother has left on my memory is that of saintliness. She was deeply religious. She would not think of taking her meals without her daily prayers. Going to the temple was one of her daily duties. It was a Vaishnava Hindu temple, dedicated to the god Vishnu, filled with carved images, the sounds of bells, and the murmurs of ancient chants. She took vows to fast for religious holidays, and kept them meticulously. Illness was no excuse for relaxing them…. To keep two or three consecutive fasts was nothing to her. ”—M. K. Gandhi

PORBANDAR, INDIA: 1869

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi came into the world in a seaside town called Porbandar in the Kathiawar Peninsula of western India. It is a place of warm breezes. The land juts out into the Arabian Sea, its ear turned to the ocean and to the world beyond.

Once a bustling port, Porbandar was now a sleepy town on the water’s edge. Outside its borders, vast tracts of the Indian subcontinent lay under the rule of the British. Scattered in between were princely states, large and small, still ruled by Indian kings.

Some were kind rulers, others tyrannical. Some were independent in name. Most quaked at the power of the British Empire on their doorsteps. In turn, the British kept an eye on the Indian royals, to make sure that none of them gained any real strength.

The kingdom of Porbandar was too small to pose any threat to the British. It consisted of a single town, on a coastal strip less than twenty-five miles wide. Its creamy-white limestone buildings earned it the name of the “White City.”

Map of British India, 1867

The British in India

The British came as traders to India—and stayed.

The East India Company had been chartered in 1600 to buy and sell spices. Over the years, the company also traded in tea, indigo, salt, silk, cotton, and other goods—among them, vast quantities of the drug opium, sold to China. Soon the company built permanent offices and took over large areas of land.

By the mid-nineteenth century, the company ran much of the country. It collected taxes. It employed an army. It was the face of the British government in India, and it ruled harshly.

In 1857, twelve years before Gandhi’s birth, a rebellion by Indian soldiers in the company army had been brutally crushed by British commanders. The company was dissolved and its powers taken over by the British government. In 1876, Queen Victoria was crowned Empress of India. This was the beginning of the British rule that came to be called “the Raj.”

The Gandhi family home, a hundred years old, with twelve rooms and three floors, stood in a narrow lane. Its thick walls kept the interior cool even in the hottest summers. In some rooms, the walls were painted with floral and geometric designs. Evening breezes blew over the rooftop, where the children played.

The women of the household ran the kitchen—chopping vegetables with great curving knife-blades, grinding millet into flour, stirring pots of lentils and rice over crackling wood-fires. They slathered rounds of flat bread with ghee made from scalded butter. The fragrance of ground spices, homemade pickles, and chutneys wafted into the central courtyard.

Mohandas lived in this house with his father, Karamchand Gandhi (“Kaba” for short), and his mother, Putliba. Putliba was Kaba Gandhi’s fourth wife. The first two had died in childbirth, and the third was childless and ill. Kaba wanted a son, so he had asked and obtained his third wife’s permission to marry Putliba. His sick third wife, however, remained living with the family until her death. The white-walled house was also home to two daughters from Kaba’s earlier marriages, Mohandas’s half sisters, and of course to Putliba and Kaba’s other children—a daughter, Raliat, and two sons, Laxmidas and Karsandas.

Kaba’s Wives

Under the law, Kaba Gandhi didn’t need his wife’s permission to marry again. Hindu men in nineteenth-century India were allowed to have more than one wife at a time.

Mohandas’s mother, Putliba, and Mohandas’s father, Kaba Gandhi

Raliat loved the new baby. She played with Mohandas and carried him everywhere, hardly putting him down for a moment. As he grew to be a toddler, she said her little brother was “restless as mercury,” unable to “sit still even for a little while. He must be either playing or roaming about.” He was mischievous, too. When they went to the marketplace, he’d chase the neighborhood dogs and tweak their ears.

Kaba Gandhi’s father had been the diwan to the ruler of Porbandar. Kaba, who held the job of letter writer and clerk, inherited his father’s high office upon his death. As a token of the promotion, the ruler presented him with a silver inkstand and inkpot. Kaba could read and write in his native Gujarati language, although, like many Indians of the time, he knew no English.

diwan | (also dewan) noun In 19th century India, the chief minister or finance minister of a princely state

Kaba was preoccupied with his work and traveled often. When the fortunes of Porbandar’s ruler waned, he began to look for work in other local kingdoms. The new baby saw little of his father.

But the women of the house loved and indulged young Mohandas. Fondly, they called him “Monia.” They played with him and teased him. While cooking delicious vegetarian meals for the family, they took care to make special sweets for Mohandas. One of the household servants in particular, Rambha, doted on him. She became his loving nurse.

Mohandas adored his mother. She was gentle yet strong. Once, a poisonous scorpion got into the house and ran over her bare feet. Everyone panicked. Mohandas cowered. But his mother simply scooped the insect up and threw it out the window.

Mohandas at age seven

Scorpions were not the only things Mohandas feared. Even in the embrace of a loving family, he was timid and struck by frequent terrors. He was afraid of the dark and of ghosts, evil spirits, and demons. He was sure they waited for him around every dark corner or lurked in twilight shadows. His nurse, Rambha, tried her best to bolster his courage. She told him to repeat the name of Rama, the god-prince of Hindu mythology, so good and noble that chanting his name was said to drive away all evil.

“Rama, Rama!” The boy intoned the holy name over and over. It did no good. Come nightfall, he could not shake his fear.

Yet the same excitable imagination that stoked anxiety also drew him to the faith of his mother. Most Hindu families mainly worshipped one—or at most a few—of the many gods in the Hindu tradition. Putliba worshipped them all! She took her son to numerous temples in the area. She even took him to one where the walls were inscribed with writings from both Hindu scriptures and the Muslim holy book, the Quran. A shy boy paying attention to his mother’s words and actions, Mohandas likely absorbed some of her open-minded religious views.

“The outstanding impression my mother has left on my memory is that of saintliness. She was deeply religious. She would not think of taking her meals without her daily prayers. Going to the temple was one of her daily duties. It was a Vaishnava Hindu temple, dedicated to the god Vishnu, filled with carved images, the sounds of bells, and the murmurs of ancient chants. She took vows to fast for religious holidays, and kept them meticulously. Illness was no excuse for relaxing them…. To keep two or three consecutive fasts was nothing to her. ”—M. K. Gandhi

Recenzii

History has been carefully intertwined with the present in this engaging and reflective book.

A reflective presentation that will inspire young peacemakers.

An in-depth and well-researched volume that complements existing YA biographies on these two individuals by forging a little-known connection between American Black activism and the Indian nonviolent movement.

A reflective presentation that will inspire young peacemakers.

An in-depth and well-researched volume that complements existing YA biographies on these two individuals by forging a little-known connection between American Black activism and the Indian nonviolent movement.

Descriere

A look at Mahatma Ghandi and Martin Luther King Jr., two very different men on a very similar mission--cultural revolution through peace; now in paperback!