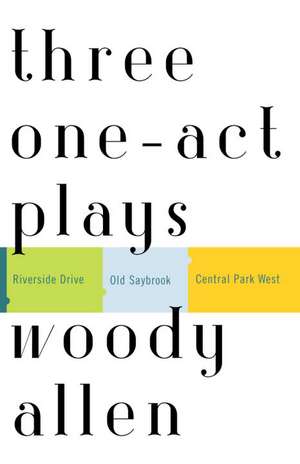

Three One-Act Plays: Riverside Drive Old Saybrook Central Park West

Autor Woody Allenen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 dec 2003

Woody Allen’s first dramatic writing published in years, “Riverside Drive,” “Old Saybrook,” and “Central Park West” are humorous, insightful, and unusually readable plays about infidelity. The characters, archetypal New Yorkers all, start out talking innocently enough, but soon the most unexpected things arise—and the reader enjoys every minute of it (though not all the characters do).

These plays (successfully produced on the New York stage and in regional theaters on the East Coast) dramatize Allen’s continuing preoccupation with people who rationalize their actions, hide what they’re doing, and inevitably slip into sexual deception—all of it revealed in Allen’s quintessentially pell-mell dialogue.

Preț: 98.71 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 148

Preț estimativ în valută:

18.89€ • 20.53$ • 15.88£

18.89€ • 20.53$ • 15.88£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 31 martie-14 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780812972443

ISBN-10: 0812972449

Pagini: 224

Dimensiuni: 133 x 205 x 12 mm

Greutate: 0.17 kg

Ediția:New.

Editura: Random House Trade

ISBN-10: 0812972449

Pagini: 224

Dimensiuni: 133 x 205 x 12 mm

Greutate: 0.17 kg

Ediția:New.

Editura: Random House Trade

Notă biografică

Woody Allen writes and directs. He lives in New York.

Extras

Chapter 1

Curtain rises on a gray day in New York. There might even be some hint of fog. The setting suggests a secluded spot by the embankment of the Hudson River where one can lean over the rail, watch the boats and see the New Jersey shoreline. Probably the West Seventies or Eighties.

Jim Swain, a writer, somewhere between forty and fifty, is waiting nervously, checking his watch, pacing, trying a number on his cellular phone to no response. He’s obviously waiting to meet someone.

He rubs his hands together, checks for some drizzle and perhaps pulls his jacket up a bit as he feels at least a damp mist.

Presently, a large, homeless man, unshaven, a street dweller of approximately Jim’s age, drifts on with a kind of eye on Jim. His name is Fred.

Fred eventually drifts closer to Jim, who has become increasingly aware of his presence and, while not exactly afraid, is wary of being in a desolate area with a large, unsavory type. Add to this that Jim wants his rendezvous with whomever he is waiting for to be very private. Finally, Fred engages him.

fred

Rainy day.

(Jim nods, agreeing but not wanting to encourage conversation.)

A drizzle.

(Jim nods with a wan smile.)

Or should I say mizzle—mist and drizzle.

jim

Um.

fred

(pause)

Look at how fast the current’s moving. You throw your cap into the river it’ll be out in the open sea in twenty minutes.

jim

(begrudging but polite)

Uh-huh . . .

fred

(pause)

The Hudson River travels three hundred and fifteen miles beginning in the Adirondacks and emptying finally into the vast Atlantic Ocean.

jim

Interesting.

fred

No it’s not. Ever wonder what it’d be like if the current ran in the opposite direction?

jim

I haven’t actually.

fred

Chaos—the world would be out of sync. You throw your cap in it’d get carried up to Poughkeepsie rather than out to sea.

jim

Yes . . . well . . .

fred

Ever been to Poughkeepsie?

jim

What?

fred

Ever been to Poughkeepsie?

jim

Me?

fred

(looks around; they’re alone)

Who else?

jim

Why do you ask?

fred

It’s a simple question.

jim

If I was in Poughkeepsie?

fred

Were you?

jim

(considers the question, decides he’ll answer)

No, I haven’t. OK?

fred

So if you haven’t, why are you so guilty?

jim

Look, I’m a little preoccupied.

fred

You don’t come here often, do you?

jim

Why?

fred

Interesting.

jim

What do you want? Are you going to hit me up for a touch? Here, here’s a buck.

fred

Hey—I only asked if you came here often.

jim

(getting impatient)

No. I’m meeting someone. I have a lot on my mind.

fred

What a day you picked.

jim

I didn’t know it would be this nasty.

fred

Don’t you watch the weather on TV? Christ, it seems that all they talk about is the goddamn weather. You really care on Riverside Drive if there are gusty winds in the Appalachian Valley? I mean, Jesus, gimme a break.

jim

Well, it was nice talking to you.

fred

Look—you can hardly see Jersey—there’s such a fog.

jim

It’s OK. It’s a blessing . . .

fred

Right. I don’t like it any better than you do.

jim

Actually I’m joking—I’m being

fred

Frivolous? . . . Flippant?

jim

Mildly sarcastic.

fred

It’s understandable.

jim

It is?

fred

Knowing how I feel about Montclair.

jim

How would I know how you feel about Montclair?

fred

I won’t even bother to comment on that.

jim

Er—yeah—well—I’d like to get back to my thoughts.

(Looks at watch.)

fred

What time you expect her?

jim

What are you talking about? Please leave me alone.

fred

It’s a free country. I can stay here and stare at New Jersey if I want.

jim

Fine. But don’t talk to me.

fred

Don’t answer.

jim

(takes out cell phone)

Hey look, do you want me to call the police?

fred

And tell them what?

jim

That you’re harassing me—aggressive panhandling.

fred

Suppose I took that cell phone and tossed it right into the river. Twenty minutes it’d be carried off into the Atlantic. Of course, if the current ran the other way it’d wind up in Poughkeepsie. Do I mean Poughkeepsie or Tarrytown?

jim

(a bit scared and angry)

I’ve been to Tarrytown in case you were going to ask me that next.

fred

Where’d you stay there?

jim

Pocantico Hills. I used to live there. Is that OK with you?

fred

Now they call it Sleepy Hollow—sounds better for the tourists.

jim

Uh-huh.

fred

Cash in on all that Ichabod Crane crap. Rip Van Winkle. It’s all packaging.

jim

Look—I was deep in thought

fred

Hey—we’re talking literature. You’re a writer.

jim

How do you know that?

fred

C’mon—it’s me.

jim

Are you going to tell me you can tell because of my costume?

fred

You’re in costume?

jim

It’s the tweed jacket and the corduroys, right?

fred

Jean-Paul Sartre said that after the age of thirty a man is responsible for his own face.

jim

Camus said that.

fred

Sartre.

jim

Camus. Sartre said a man assumes the traits of his occupation—a waiter will gradually walk like a waiter—a bank clerk gestures like one—because they want to become things.

fred

But you’re not a thing.

jim

I try not to be.

fred

Because it’s safe to be a thing—because things don’t perish. Like The Wall—the men being executed want to become one with the wall they’re put up in front of—to lose themselves in the stone—to become solid, permanent, to endure, in other words, to live, to be alive.

jim

(considers him—then)

I’d love to discuss this with you another time.

fred

Good, when?

jim

Right now I’m a little busy . . .

fred

Well, when? You want to have lunch, I’m free all week.

jim

I don’t really know.

fred

I wrote a funny thing based on Irving.

jim

Irving who?

fred

Washington Irving—remember? We had talked about Ichabod Crane.

jim

I didn’t know we were back on that.

fred

The headless horseman is doomed to ride the countryside, holding his head under his arm. He was a German soldier killed in the war.

jim

A Hessian.

fred

So he rides right into an all-night drugstore and the head says—I have a terrible headache—and the druggist says, here, take these two Extra Strength Excedrin—and the body pays for them and helps the head take two. And then we cut to them later in the night, riding over a bridge, and the head says, I feel great—the headache is gone—I’m a new man—and then the body begins to get sad and thinks how unlucky he is because if he gets a backache, he can’t find relief, not being attached to the head

jim

How can the body think anything?

fred

Nobody’s going to ask that question.

jim

Why not? It’s obvious.

fred

That’s why. That’s why you’re good at construction and dialogue but you lack inspiration. That’s why you have to rely on me. Although it was a pretty sleazy thing to do.

jim

Do what? What are you talking about?

fred

I’m talking about money—some kind of payment and a credit of some sort.

jim

Look, I’m meeting someone.

fred

I know, I know, she’s late.

jim

You don’t know and mind your own business.

fred

All right—you’re meeting a broad—you want to be alone? Let’s get the business end of it out of the way and I’m off.

jim

What business?

fred

In a minute you’re gonna tell me this whole thing is Kafkaesque.

jim

It’s worse than Kafkaesque.

fred

Really? Is it—postmodern?

jim

What do you want?

fred

A percentage and a credit on your movie. I realize it’s too late for a credit on the prints that are already in distribution, but I should have a royalty on those and a cut and my name on all subsequent prints. Not fifty percent but something fair.

jim

Are you nuts? Why should I give you anything?

fred

Because I gave you the idea.

jim

You gave me?

fred

Well—you took it from me

jim

I took your idea?

fred

And you sold your first film script—and the movie seems like a success and I want what’s due me.

jim

I didn’t take your idea.

fred

Jim, let’s not play games.

jim

Let’s not you play games and don’t call me Jim.

fred

OK—James. Written by James L. Swain—but everyone calls you Jim.

jim

How do you know what everyone calls me?

fred

I see it, I hear it.

jim

Where? What are you talking about?

fred

Jim Swain—Central Park West and Seventy-eighth—BMW—license plate JIMBO ONE—talk about vanity plates . . . Jimmy Connors is Jimbo One, not you—and I’ve seen you trying to hit a tennis ball so don’t try and con me.

jim

Have you been following me?

fred

That mousey brunette—that’s Lola?

jim

My wife’s hardly mousey!

fred

OK, “mousey” was the wrong word—she’s—not rodentine exactly

jim

She’s a beautiful woman.

fred

It’s all very subjective.

jim

Who the hell do you think you are?

fred

I’d never say it to her face.

jim

I’m her husband and I love her.

fred

Then why are you cheating?

jim

What?

fred

I think I know what the other one looks like. She’s a little on the cheap side, no?

jim

There is no other one.

fred

Then who are you meeting?

jim

None of your goddamn business, and if you don’t get out of here I’m going to call the police.

fred

That’s the last thing you want if you’re having a clandestine rendezvous.

jim

How did you know my wife’s name is Lola?

fred

I’ve heard you call her Lola.

jim

Have you been stalking me?

fred

Do I look like a stalker?

jim

Yes.

fred

I’m a writer. At least I was years ago. Till my visions overtook me.

jim

Well, your imagination is too creative for me.

fred

I know. That’s why you ripped me off.

jim

I didn’t steal your idea.

fred

Not just my idea. It was autobiographical. So in a way you stole my life.

jim

If there were any similarities between my film and your life, I assure you, they’re coincidental.

fred

I’m not the kind of guy who sues. Some people are litigation-prone.

(with some suggestion of menace)

I like to settle between the parties.

jim

How did I take your idea?

fred

You overheard me tell the plot.

jim

To who? Where?

fred

Central Park.

jim

I heard you in Central Park?

fred

That’s right.

jim

To who? When?

fred

To John.

jim

Who?

fred

John.

jim

John who?

fred

Big John.

jim

Who?

fred

Big John.

jim

Who the hell is Big John?

fred

I don’t know—he’s a homeless guy. Was. I heard he got his throat cut in a shelter.

jim

You told some tale to a homeless man and you’re saying I overheard you?

fred

And used it.

jim

I never saw you in my life.

fred

Christ, I’ve been stalking you for months.

jim

Stalking me?

fred

And I know everything about you but you never even noticed me. And I’m not a little guy. I’m big. I could probably snap your neck in half with one hand.

jim

(nervous)

Look—whoever you are, I promise

fred

The name’s Fred. Fred Savage. Good name for a writer, isn’t it? For Best Original Screenplay, the envelope please—and the winners are Frederick R. Savage and James L. Swain for The Journey.

jim

I wrote The Journey. And it was my idea.

fred

Jim, you overheard me telling it to John Kelly. Poor John. He was walking on York Avenue and they were hoisting a piano and the rope came undone—God, it was awful . . .

jim

You said he was knifed at a shelter.

fred

Foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of small minds.

jim

Look, Fred—I never stole anybody’s idea. First, I don’t need to because I have my own ideas, and second, I wouldn’t even if I ran dry, OK?

fred

But the story’s all there. My breakdown, the straitjacket, my last-minute panic—the rubber between my teeth, then the electric shocks—my God—of course I was violent

jim

You’re violent?

fred

In and out.

jim

Look, I’m starting to get a little alarmed.

fred

Don’t worry, she’ll be here.

jim

Over you, not her. OK—if you think you’re a writer

fred

I said years ago—before my collapse—before all that unpleasantness occurred—I wrote for an agency.

jim

Unpleasantness?

fred

It’s morbid, I don’t want to relive it.

jim

What kind of an agency?

fred

An ad agency. I wrote commercials. Like that idea for the Extra Strength Excedrin one. It didn’t fly. We ran it up the flagpole but it just didn’t fly. Too Cartesian.

jim

And you became—unhinged.

fred

Not over that. Who cares that they reject my idea? Those gray flannel philistines. No, my problem arose from other sources.

jim

Like what?

fred

Like small cadres of men who had banded together to form a conspiratorial network—a network dedicated to my undoing, to my humiliation, to my defeat both physical and mental. A network so vast and complex that to this day it employs undercover agents in organizations as diverse as the CIA and the Cuban underground. Forces so malevolent that they cost me my job, my marriage, and what little bank account I had left. They trailed me, tapped my phone, and communicated in code with my psychiatrist by sending electrical signals from the top of the Empire State Building, through my inner ear, directly to his rubber raft at Martha’s Vineyard. So don’t give me your goddamn sob stories and deal with me like a mensch!

jim

I’m frightened, Fred—I gotta level with you. I want to do the right thing by you

fred

Then do it. There’s no need to be scared. I haven’t been off my medicine long enough to lose control—at least I don’t think I have

jim

What do you take?

fred

A number of antipsychotic mixtures.

jim

A cocktail.

fred

Except I don’t drink it out of a stemmed glass.

jim

But you can’t just go off those things

fred

I’m fine, I’m fine. Don’t start accusing me like the others.

jim

No, I’m not

fred

Let’s talk turkey.

jim

I had intended to prove to you logically I couldn’t have taken your idea

fred

My life, my life—you stole my life.

jim

Your life—your autobiography, whatever. I think I can show you step by step

fred

Logic can be very deceptive. You stole my life, you stole my soul.

jim

I don’t need your life. I have a fine life of my own.

fred

Who are you to say you don’t need my life?

Curtain rises on a gray day in New York. There might even be some hint of fog. The setting suggests a secluded spot by the embankment of the Hudson River where one can lean over the rail, watch the boats and see the New Jersey shoreline. Probably the West Seventies or Eighties.

Jim Swain, a writer, somewhere between forty and fifty, is waiting nervously, checking his watch, pacing, trying a number on his cellular phone to no response. He’s obviously waiting to meet someone.

He rubs his hands together, checks for some drizzle and perhaps pulls his jacket up a bit as he feels at least a damp mist.

Presently, a large, homeless man, unshaven, a street dweller of approximately Jim’s age, drifts on with a kind of eye on Jim. His name is Fred.

Fred eventually drifts closer to Jim, who has become increasingly aware of his presence and, while not exactly afraid, is wary of being in a desolate area with a large, unsavory type. Add to this that Jim wants his rendezvous with whomever he is waiting for to be very private. Finally, Fred engages him.

fred

Rainy day.

(Jim nods, agreeing but not wanting to encourage conversation.)

A drizzle.

(Jim nods with a wan smile.)

Or should I say mizzle—mist and drizzle.

jim

Um.

fred

(pause)

Look at how fast the current’s moving. You throw your cap into the river it’ll be out in the open sea in twenty minutes.

jim

(begrudging but polite)

Uh-huh . . .

fred

(pause)

The Hudson River travels three hundred and fifteen miles beginning in the Adirondacks and emptying finally into the vast Atlantic Ocean.

jim

Interesting.

fred

No it’s not. Ever wonder what it’d be like if the current ran in the opposite direction?

jim

I haven’t actually.

fred

Chaos—the world would be out of sync. You throw your cap in it’d get carried up to Poughkeepsie rather than out to sea.

jim

Yes . . . well . . .

fred

Ever been to Poughkeepsie?

jim

What?

fred

Ever been to Poughkeepsie?

jim

Me?

fred

(looks around; they’re alone)

Who else?

jim

Why do you ask?

fred

It’s a simple question.

jim

If I was in Poughkeepsie?

fred

Were you?

jim

(considers the question, decides he’ll answer)

No, I haven’t. OK?

fred

So if you haven’t, why are you so guilty?

jim

Look, I’m a little preoccupied.

fred

You don’t come here often, do you?

jim

Why?

fred

Interesting.

jim

What do you want? Are you going to hit me up for a touch? Here, here’s a buck.

fred

Hey—I only asked if you came here often.

jim

(getting impatient)

No. I’m meeting someone. I have a lot on my mind.

fred

What a day you picked.

jim

I didn’t know it would be this nasty.

fred

Don’t you watch the weather on TV? Christ, it seems that all they talk about is the goddamn weather. You really care on Riverside Drive if there are gusty winds in the Appalachian Valley? I mean, Jesus, gimme a break.

jim

Well, it was nice talking to you.

fred

Look—you can hardly see Jersey—there’s such a fog.

jim

It’s OK. It’s a blessing . . .

fred

Right. I don’t like it any better than you do.

jim

Actually I’m joking—I’m being

fred

Frivolous? . . . Flippant?

jim

Mildly sarcastic.

fred

It’s understandable.

jim

It is?

fred

Knowing how I feel about Montclair.

jim

How would I know how you feel about Montclair?

fred

I won’t even bother to comment on that.

jim

Er—yeah—well—I’d like to get back to my thoughts.

(Looks at watch.)

fred

What time you expect her?

jim

What are you talking about? Please leave me alone.

fred

It’s a free country. I can stay here and stare at New Jersey if I want.

jim

Fine. But don’t talk to me.

fred

Don’t answer.

jim

(takes out cell phone)

Hey look, do you want me to call the police?

fred

And tell them what?

jim

That you’re harassing me—aggressive panhandling.

fred

Suppose I took that cell phone and tossed it right into the river. Twenty minutes it’d be carried off into the Atlantic. Of course, if the current ran the other way it’d wind up in Poughkeepsie. Do I mean Poughkeepsie or Tarrytown?

jim

(a bit scared and angry)

I’ve been to Tarrytown in case you were going to ask me that next.

fred

Where’d you stay there?

jim

Pocantico Hills. I used to live there. Is that OK with you?

fred

Now they call it Sleepy Hollow—sounds better for the tourists.

jim

Uh-huh.

fred

Cash in on all that Ichabod Crane crap. Rip Van Winkle. It’s all packaging.

jim

Look—I was deep in thought

fred

Hey—we’re talking literature. You’re a writer.

jim

How do you know that?

fred

C’mon—it’s me.

jim

Are you going to tell me you can tell because of my costume?

fred

You’re in costume?

jim

It’s the tweed jacket and the corduroys, right?

fred

Jean-Paul Sartre said that after the age of thirty a man is responsible for his own face.

jim

Camus said that.

fred

Sartre.

jim

Camus. Sartre said a man assumes the traits of his occupation—a waiter will gradually walk like a waiter—a bank clerk gestures like one—because they want to become things.

fred

But you’re not a thing.

jim

I try not to be.

fred

Because it’s safe to be a thing—because things don’t perish. Like The Wall—the men being executed want to become one with the wall they’re put up in front of—to lose themselves in the stone—to become solid, permanent, to endure, in other words, to live, to be alive.

jim

(considers him—then)

I’d love to discuss this with you another time.

fred

Good, when?

jim

Right now I’m a little busy . . .

fred

Well, when? You want to have lunch, I’m free all week.

jim

I don’t really know.

fred

I wrote a funny thing based on Irving.

jim

Irving who?

fred

Washington Irving—remember? We had talked about Ichabod Crane.

jim

I didn’t know we were back on that.

fred

The headless horseman is doomed to ride the countryside, holding his head under his arm. He was a German soldier killed in the war.

jim

A Hessian.

fred

So he rides right into an all-night drugstore and the head says—I have a terrible headache—and the druggist says, here, take these two Extra Strength Excedrin—and the body pays for them and helps the head take two. And then we cut to them later in the night, riding over a bridge, and the head says, I feel great—the headache is gone—I’m a new man—and then the body begins to get sad and thinks how unlucky he is because if he gets a backache, he can’t find relief, not being attached to the head

jim

How can the body think anything?

fred

Nobody’s going to ask that question.

jim

Why not? It’s obvious.

fred

That’s why. That’s why you’re good at construction and dialogue but you lack inspiration. That’s why you have to rely on me. Although it was a pretty sleazy thing to do.

jim

Do what? What are you talking about?

fred

I’m talking about money—some kind of payment and a credit of some sort.

jim

Look, I’m meeting someone.

fred

I know, I know, she’s late.

jim

You don’t know and mind your own business.

fred

All right—you’re meeting a broad—you want to be alone? Let’s get the business end of it out of the way and I’m off.

jim

What business?

fred

In a minute you’re gonna tell me this whole thing is Kafkaesque.

jim

It’s worse than Kafkaesque.

fred

Really? Is it—postmodern?

jim

What do you want?

fred

A percentage and a credit on your movie. I realize it’s too late for a credit on the prints that are already in distribution, but I should have a royalty on those and a cut and my name on all subsequent prints. Not fifty percent but something fair.

jim

Are you nuts? Why should I give you anything?

fred

Because I gave you the idea.

jim

You gave me?

fred

Well—you took it from me

jim

I took your idea?

fred

And you sold your first film script—and the movie seems like a success and I want what’s due me.

jim

I didn’t take your idea.

fred

Jim, let’s not play games.

jim

Let’s not you play games and don’t call me Jim.

fred

OK—James. Written by James L. Swain—but everyone calls you Jim.

jim

How do you know what everyone calls me?

fred

I see it, I hear it.

jim

Where? What are you talking about?

fred

Jim Swain—Central Park West and Seventy-eighth—BMW—license plate JIMBO ONE—talk about vanity plates . . . Jimmy Connors is Jimbo One, not you—and I’ve seen you trying to hit a tennis ball so don’t try and con me.

jim

Have you been following me?

fred

That mousey brunette—that’s Lola?

jim

My wife’s hardly mousey!

fred

OK, “mousey” was the wrong word—she’s—not rodentine exactly

jim

She’s a beautiful woman.

fred

It’s all very subjective.

jim

Who the hell do you think you are?

fred

I’d never say it to her face.

jim

I’m her husband and I love her.

fred

Then why are you cheating?

jim

What?

fred

I think I know what the other one looks like. She’s a little on the cheap side, no?

jim

There is no other one.

fred

Then who are you meeting?

jim

None of your goddamn business, and if you don’t get out of here I’m going to call the police.

fred

That’s the last thing you want if you’re having a clandestine rendezvous.

jim

How did you know my wife’s name is Lola?

fred

I’ve heard you call her Lola.

jim

Have you been stalking me?

fred

Do I look like a stalker?

jim

Yes.

fred

I’m a writer. At least I was years ago. Till my visions overtook me.

jim

Well, your imagination is too creative for me.

fred

I know. That’s why you ripped me off.

jim

I didn’t steal your idea.

fred

Not just my idea. It was autobiographical. So in a way you stole my life.

jim

If there were any similarities between my film and your life, I assure you, they’re coincidental.

fred

I’m not the kind of guy who sues. Some people are litigation-prone.

(with some suggestion of menace)

I like to settle between the parties.

jim

How did I take your idea?

fred

You overheard me tell the plot.

jim

To who? Where?

fred

Central Park.

jim

I heard you in Central Park?

fred

That’s right.

jim

To who? When?

fred

To John.

jim

Who?

fred

John.

jim

John who?

fred

Big John.

jim

Who?

fred

Big John.

jim

Who the hell is Big John?

fred

I don’t know—he’s a homeless guy. Was. I heard he got his throat cut in a shelter.

jim

You told some tale to a homeless man and you’re saying I overheard you?

fred

And used it.

jim

I never saw you in my life.

fred

Christ, I’ve been stalking you for months.

jim

Stalking me?

fred

And I know everything about you but you never even noticed me. And I’m not a little guy. I’m big. I could probably snap your neck in half with one hand.

jim

(nervous)

Look—whoever you are, I promise

fred

The name’s Fred. Fred Savage. Good name for a writer, isn’t it? For Best Original Screenplay, the envelope please—and the winners are Frederick R. Savage and James L. Swain for The Journey.

jim

I wrote The Journey. And it was my idea.

fred

Jim, you overheard me telling it to John Kelly. Poor John. He was walking on York Avenue and they were hoisting a piano and the rope came undone—God, it was awful . . .

jim

You said he was knifed at a shelter.

fred

Foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of small minds.

jim

Look, Fred—I never stole anybody’s idea. First, I don’t need to because I have my own ideas, and second, I wouldn’t even if I ran dry, OK?

fred

But the story’s all there. My breakdown, the straitjacket, my last-minute panic—the rubber between my teeth, then the electric shocks—my God—of course I was violent

jim

You’re violent?

fred

In and out.

jim

Look, I’m starting to get a little alarmed.

fred

Don’t worry, she’ll be here.

jim

Over you, not her. OK—if you think you’re a writer

fred

I said years ago—before my collapse—before all that unpleasantness occurred—I wrote for an agency.

jim

Unpleasantness?

fred

It’s morbid, I don’t want to relive it.

jim

What kind of an agency?

fred

An ad agency. I wrote commercials. Like that idea for the Extra Strength Excedrin one. It didn’t fly. We ran it up the flagpole but it just didn’t fly. Too Cartesian.

jim

And you became—unhinged.

fred

Not over that. Who cares that they reject my idea? Those gray flannel philistines. No, my problem arose from other sources.

jim

Like what?

fred

Like small cadres of men who had banded together to form a conspiratorial network—a network dedicated to my undoing, to my humiliation, to my defeat both physical and mental. A network so vast and complex that to this day it employs undercover agents in organizations as diverse as the CIA and the Cuban underground. Forces so malevolent that they cost me my job, my marriage, and what little bank account I had left. They trailed me, tapped my phone, and communicated in code with my psychiatrist by sending electrical signals from the top of the Empire State Building, through my inner ear, directly to his rubber raft at Martha’s Vineyard. So don’t give me your goddamn sob stories and deal with me like a mensch!

jim

I’m frightened, Fred—I gotta level with you. I want to do the right thing by you

fred

Then do it. There’s no need to be scared. I haven’t been off my medicine long enough to lose control—at least I don’t think I have

jim

What do you take?

fred

A number of antipsychotic mixtures.

jim

A cocktail.

fred

Except I don’t drink it out of a stemmed glass.

jim

But you can’t just go off those things

fred

I’m fine, I’m fine. Don’t start accusing me like the others.

jim

No, I’m not

fred

Let’s talk turkey.

jim

I had intended to prove to you logically I couldn’t have taken your idea

fred

My life, my life—you stole my life.

jim

Your life—your autobiography, whatever. I think I can show you step by step

fred

Logic can be very deceptive. You stole my life, you stole my soul.

jim

I don’t need your life. I have a fine life of my own.

fred

Who are you to say you don’t need my life?