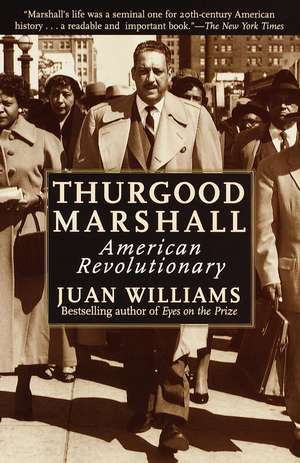

Thurgood Marshall: American Revolutionary

Autor Juan Williamsen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 ian 2000 – vârsta de la 15 până la 18 ani

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

From the bestselling author of Eyes on the Prize, here is the definitive biography of the great lawyer and Supreme Court justice.

Preț: 112.80 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 169

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.60€ • 22.26$ • 18.13£

21.60€ • 22.26$ • 18.13£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 01-15 februarie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780812932997

ISBN-10: 0812932994

Pagini: 504

Ilustrații: 37 B&W PHOTOS;1 16P B&W INSERT

Dimensiuni: 129 x 210 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.41 kg

Ediția:Pbk.

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0812932994

Pagini: 504

Ilustrații: 37 B&W PHOTOS;1 16P B&W INSERT

Dimensiuni: 129 x 210 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.41 kg

Ediția:Pbk.

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

Notă biografică

Juan Williams has been a political analyst and national correspondent for The Washington Post for twenty-one years. He has written for Fortune,The Atlantic Monthly, Ebony, GQ, and Newsweek, for which he is a regular columnist. Mr. Williams has earned widespread critical acclaim for a series of documentaries, including one that won him an Emmy Award. His numerous and frequent television appearances include Oprah, Nightline, Washington Week in Review, CNN's Crossfire (where he often served as co-host), and Capitol Gang Sunday. Currently a regular panelist on Fox News Sunday, he lives in Washington, D.C.

Extras

Right Time, Right Man?

Rumors flew that night. Supreme Court Justice Tom Clark had resigned a few hours earlier. By that Monday evening, Solicitor General Thurgood Marshall and his wife, Cissy, heard that the president was set to name Clark's replacement the very next morning. At the Marshalls' small green town house on G Street in Southwest Washington, D.C., the phone was ringing. Friends, family, and even politicians were calling to see if Thurgood had heard anything about his chances for the job. But all the Marshalls could say was that they had heard rumors.

As Marshall dressed for Clark's retirement party on that muggy Washington night of June 12, 1967, he looked at his reflection in the mirror. Years ago some of his militant critics had called him "half-white" for his straight hair, pointed nose, and light tan skin. Now, at fifty-eight, his face had grown heavy, with sagging jowls and dark bags under his eyes. His once black hair, even his mustache, was now mostly a steely gray. And he looked worried. He did have on a good dark blue suit, the uniform of a Washington power player. But the conservative suit looked old and out of place in an era of Afros and dashikis. And even the best suit might not be strong enough armor for the high-stakes political fight he was preparing for tonight. At this moment the six-foot-two-inch Marshall, who weighed well over two hundred pounds, felt powerless. He was fearful that he was about to lose his only chance to become a Supreme Court justice.

Staring in the mirror as if it were a crystal ball, Marshall could see clearly only that he would have one last chance to convince the president he was the right man. That chance would come tonight at Justice Clark's retirement party.

In his two years as solicitor general there had been constant rumors floating around the capital about Marshall being positioned by the president to become the first black man on the high court. However, with one exception, no one at the White House had ever spoken to him about the job. That exception was President Lyndon Johnson. Whenever Johnson talked about the Supreme Court in front of him, the tall, intense Texan made a point of turning to Marshall, thrusting a finger in his face, and reminding him there was no promise that he would ever have a job on the high court.

But Johnson was privately talking about putting Marshall on the Supreme Court. For a southern politician, Johnson had a strong sense of racial justice. As a skinny twenty-year-old, he had taught school to poor Hispanic children in south Texas and seen firsthand the disadvantages they faced. Now Johnson's fabled political instincts had drawn him to the idea that he would be hailed by history as the president who put the first black on the Supreme Court. The president had set the wheels in motion by making Marshall the nation's first black solicitor general. And he had confided to his wife, Lady Bird, that he wanted to appoint Marshall to the Supreme Court. But the president had been having second thoughts about Marshall. Was he really a good lawyer? And what about talk that Marshall was lazy? Was it realistic to think he could win enough votes to get by white racists in the Senate and be confirmed?

As he finished getting ready for the party, Marshall replayed all the rumors he had heard about why the president was reluctant to appoint him to the high court. Thinking about it, Marshall got grumpy, then angry. His chance to be in the history books as the first black man on the Supreme Court was fading, and he felt abandoned. The word around the capital was that the nomination would be announced tomorrow. Marshall had heard nothing from the White House.

Rumors flew that night. Supreme Court Justice Tom Clark had resigned a few hours earlier. By that Monday evening, Solicitor General Thurgood Marshall and his wife, Cissy, heard that the president was set to name Clark's replacement the very next morning. At the Marshalls' small green town house on G Street in Southwest Washington, D.C., the phone was ringing. Friends, family, and even politicians were calling to see if Thurgood had heard anything about his chances for the job. But all the Marshalls could say was that they had heard rumors.

As Marshall dressed for Clark's retirement party on that muggy Washington night of June 12, 1967, he looked at his reflection in the mirror. Years ago some of his militant critics had called him "half-white" for his straight hair, pointed nose, and light tan skin. Now, at fifty-eight, his face had grown heavy, with sagging jowls and dark bags under his eyes. His once black hair, even his mustache, was now mostly a steely gray. And he looked worried. He did have on a good dark blue suit, the uniform of a Washington power player. But the conservative suit looked old and out of place in an era of Afros and dashikis. And even the best suit might not be strong enough armor for the high-stakes political fight he was preparing for tonight. At this moment the six-foot-two-inch Marshall, who weighed well over two hundred pounds, felt powerless. He was fearful that he was about to lose his only chance to become a Supreme Court justice.

Staring in the mirror as if it were a crystal ball, Marshall could see clearly only that he would have one last chance to convince the president he was the right man. That chance would come tonight at Justice Clark's retirement party.

In his two years as solicitor general there had been constant rumors floating around the capital about Marshall being positioned by the president to become the first black man on the high court. However, with one exception, no one at the White House had ever spoken to him about the job. That exception was President Lyndon Johnson. Whenever Johnson talked about the Supreme Court in front of him, the tall, intense Texan made a point of turning to Marshall, thrusting a finger in his face, and reminding him there was no promise that he would ever have a job on the high court.

But Johnson was privately talking about putting Marshall on the Supreme Court. For a southern politician, Johnson had a strong sense of racial justice. As a skinny twenty-year-old, he had taught school to poor Hispanic children in south Texas and seen firsthand the disadvantages they faced. Now Johnson's fabled political instincts had drawn him to the idea that he would be hailed by history as the president who put the first black on the Supreme Court. The president had set the wheels in motion by making Marshall the nation's first black solicitor general. And he had confided to his wife, Lady Bird, that he wanted to appoint Marshall to the Supreme Court. But the president had been having second thoughts about Marshall. Was he really a good lawyer? And what about talk that Marshall was lazy? Was it realistic to think he could win enough votes to get by white racists in the Senate and be confirmed?

As he finished getting ready for the party, Marshall replayed all the rumors he had heard about why the president was reluctant to appoint him to the high court. Thinking about it, Marshall got grumpy, then angry. His chance to be in the history books as the first black man on the Supreme Court was fading, and he felt abandoned. The word around the capital was that the nomination would be announced tomorrow. Marshall had heard nothing from the White House.

Recenzii

"Marshall's life was a seminal one for twentieth-century American history, and it is well told in Mr. Williams's readable and important book."--The New York Times

"This is a must-read for all Americans concerned with the struggle for civil and individual rights."--Booklist (Editors' Choice, 1998)

"Engaging--remarkable in its vivid and detailed account of its subject."--The Washington Post Book World

"Magisterial." --Time magazine

"This is a must-read for all Americans concerned with the struggle for civil and individual rights."--Booklist (Editors' Choice, 1998)

"Engaging--remarkable in its vivid and detailed account of its subject."--The Washington Post Book World

"Magisterial." --Time magazine

Descriere

The bestselling author of "Eyes on the Prize" has written the definitive biography of the great lawyer and Supreme Court justice, now in trade paper. of photos.

Premii

- Black Caucus of the American Library Association Literary_award Honor Book, 1999