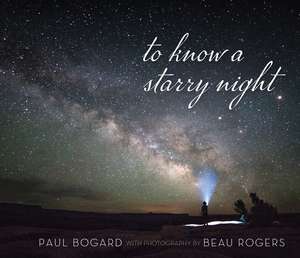

To Know a Starry Night

Autor Paul Bogard Fotograf Beau Rogersen Limba Engleză Hardback – 11 oct 2021 – vârsta ani

“Against a backdrop rich with purples, blues, and shades of black, a blaze of stars glittering across a vast empty sky spurs our curiosity about the past, driving us inevitably to ponder the future. For millennia, the night sky has been a collective canvas for our stories, maps, traditions, beliefs, and discoveries. Over the course of time, continents have formed and eroded, sea levels have risen and fallen, the chemistry of our atmosphere has changed, and yet the daily cycle of light to dark has remained pretty much the same . . . until the last 100 years.”

—Karen Trevino, from the foreword

No matter where we live, what language we speak, or what culture shapes our worldview, there is always the night. The darkness is a reminder of the ebb and flow, of an opportunity to recharge, of the movement of time. But how many of us have taken the time to truly know a starry night? To really know it.

Combining the lyrical writing of Paul Bogard with the stunning night-sky photography of Beau Rogers, To Know a Starry Night explores the powerful experience of being outside under a natural starry sky\--how important it is to human life, and how so many people don’t know this experience. As the night sky increasingly becomes flooded with artificial-light pollution, this poignant work helps us reconnect with the natural darkness of night, an experience that now, in our time, is fading from our lives.

—Karen Trevino, from the foreword

No matter where we live, what language we speak, or what culture shapes our worldview, there is always the night. The darkness is a reminder of the ebb and flow, of an opportunity to recharge, of the movement of time. But how many of us have taken the time to truly know a starry night? To really know it.

Combining the lyrical writing of Paul Bogard with the stunning night-sky photography of Beau Rogers, To Know a Starry Night explores the powerful experience of being outside under a natural starry sky\--how important it is to human life, and how so many people don’t know this experience. As the night sky increasingly becomes flooded with artificial-light pollution, this poignant work helps us reconnect with the natural darkness of night, an experience that now, in our time, is fading from our lives.

Preț: 336.67 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 505

Preț estimativ în valută:

64.42€ • 68.89$ • 53.71£

64.42€ • 68.89$ • 53.71£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781647790127

ISBN-10: 1647790123

Pagini: 144

Ilustrații: 79 color photos

Dimensiuni: 241 x 241 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.92 kg

Editura: University of Nevada Press

Colecția University of Nevada Press

ISBN-10: 1647790123

Pagini: 144

Ilustrații: 79 color photos

Dimensiuni: 241 x 241 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.92 kg

Editura: University of Nevada Press

Colecția University of Nevada Press

Recenzii

“More than the lyricism of Bogard’s prose and the beauty of Rogers’ photography, the book can be taken as a wakeup call to get out there and be alone with the night—if we can find one without the neighbor’s spotlights.”

—Youth Services Book Review

“Paul Bogard is the unofficial poet laureate of dark skies. This is a terrific work.”

—Christopher Cokinos, author of Hope Is the Thing with Feathers and The Fallen Sky

“Paul Bogard is a friend to International Dark-Sky Association and to the cause of protecting dark skies around the world. . . . While there are many vital reasons to reduce and control the use of artificial light at night--the waste of money and energy, the needless carbon emissions, the impacts on human and environmental health--it's this loss of the night sky experience that, in the end, inspires us to our work. To Know a Starry Night is a beautiful testament to the night and will inspire readers around the world with a new—or renewed—desire to have this experience as their own.”

—Ruskin Hartley, International Dark-Sky Association

“Paul Bogard brings attention to what we have lost, how our night skies are fading and growing dimmer over time, and how we can strive to protect our starry nights.”

—Roberta Moore, co-editor of Wild Nevada

"As an astronomer, I think I know the night sky. But Paul and Beau's book reminds me I mostly know it in small pieces on camera monitors and telescope displays. Through their prose and photographs I am reminded that in reality the night is a multisensory experience, one that includes mind as well as emotion, feeling as well as seeing. Their book is a beautiful testament to how much of ourselves we lose as our city lights obscure the stars."

—Dr. Tyler Nordgren, astronomer and artist

“An ode to joy of contemplating the starry sky. . . . The wonderful photographs by Beau Rogers will urge you to search for a dark place to see a star-filled night sky, and Paul will show how to reconcile yourself with the real night, or discover it for the first time. To savor it, to sip it in its complete essence, with your dark-adapted sight, with its sounds, its scents, its temperature, all different from their day counterparts.”

—Fabio Falchi, author of The World Atlas of Light Pollution, ISTIL - Light Pollution Science and Technology Institute

—Youth Services Book Review

“Paul Bogard is the unofficial poet laureate of dark skies. This is a terrific work.”

—Christopher Cokinos, author of Hope Is the Thing with Feathers and The Fallen Sky

“Paul Bogard is a friend to International Dark-Sky Association and to the cause of protecting dark skies around the world. . . . While there are many vital reasons to reduce and control the use of artificial light at night--the waste of money and energy, the needless carbon emissions, the impacts on human and environmental health--it's this loss of the night sky experience that, in the end, inspires us to our work. To Know a Starry Night is a beautiful testament to the night and will inspire readers around the world with a new—or renewed—desire to have this experience as their own.”

—Ruskin Hartley, International Dark-Sky Association

“Paul Bogard brings attention to what we have lost, how our night skies are fading and growing dimmer over time, and how we can strive to protect our starry nights.”

—Roberta Moore, co-editor of Wild Nevada

"As an astronomer, I think I know the night sky. But Paul and Beau's book reminds me I mostly know it in small pieces on camera monitors and telescope displays. Through their prose and photographs I am reminded that in reality the night is a multisensory experience, one that includes mind as well as emotion, feeling as well as seeing. Their book is a beautiful testament to how much of ourselves we lose as our city lights obscure the stars."

—Dr. Tyler Nordgren, astronomer and artist

“An ode to joy of contemplating the starry sky. . . . The wonderful photographs by Beau Rogers will urge you to search for a dark place to see a star-filled night sky, and Paul will show how to reconcile yourself with the real night, or discover it for the first time. To savor it, to sip it in its complete essence, with your dark-adapted sight, with its sounds, its scents, its temperature, all different from their day counterparts.”

—Fabio Falchi, author of The World Atlas of Light Pollution, ISTIL - Light Pollution Science and Technology Institute

Notă biografică

Paul Bogard is the author of several books, including The End of Night and The Ground Beneath Us. He is also the author/editor of Let There Be Night. A native Minnesotan, Bogard is now an associate professor of English at Hamline University in Saint Paul, Minnesota, where he teaches writing and environmental literature. For more information, visit paul-bogard.com.

Beau Rogers leads photography workshops across the American West and teaches English at Mohave Community College’s Bullhead City, Arizona, campus. For more information, visit GoWest.photography.com.

Beau Rogers leads photography workshops across the American West and teaches English at Mohave Community College’s Bullhead City, Arizona, campus. For more information, visit GoWest.photography.com.

Extras

Darkness

"In a dark time/the eye begins to see." -Theodore Roethke, In a Dark Time

On the darkest night I have ever known I said goodbye to a friend and started walking back to my family's cabin. Between those points lay a hundred yards of dark woods, maybe the darkest they had ever been. It was a cloudy night with no moon or stars, and only a few lights around the lake. Seven years old, I walked slowly-eyes adjusting as they could, dry pine needles beneath my steps-until I made it about halfway, then stopped. I could no longer see the light from my neighbor's doorway and could not yet see the light from ours. I couldn't even see my hand before my face. The woods around me were filled with animals beginning to move, to use the cover of darkness to live. In the ground beneath me, in a constant dark, were the countless creatures that keep the forest soil alive. Above me, beyond the clouds, were layered blankets of stars. Inside me, amid the dark miracles of blood, muscle, and bone, my heart beat fast. But otherwise, I was alone. In this darkness I felt submerged, the presence pressing from all sides. I looked up past the pines to where, on a clear night, constellations would shine, but tonight a cloudy black wool came down to the treetops. Who knew what else this darkness might hold? When I caught brief sight through the pines of our cabin door's glow, I took off.

I ran down the one-lane road, sandy gravel kicked behind and didn't stop until I reached the light. I raced across the front yard-the same yard where for a lifetime I have stood in awe beneath the Milky Way-and didn't pause in leaving the dark behind.

I think of that darkness now, so many years later. Peppered with stars, washed by moonlight, the same natural darkness every night for all of time before that moment. I feel grateful to have known it as a child, to have such darkness a part of me that won't ever leave.

***

I want my daughter to know darkness like this. But the darkest place I have ever been, the darkness of my childhood, no longer exists. We are lucky, the place we have known—the lake (though not as clear) and woods (though splotched with more houses)—still more or less exists. But the darkness I knew then has faded. The ever-larger small towns to the northwest and south have made sure of that. There simply is more light on the horizon and overhead. And so, the night sky I knew as a child is gone because the darkness that held that sky is gone.

The term "shifting environmental baseline" describes how each new generation marks as reality the world as they experience it and the reality against which they will judge any change. But if that reality has been steadily diminished through the years, each new generation knows a living world less abundant and diverse than did those who came before. It's the idea that my two-year-old will never know the darkness I knew in these woods four decades ago, but when we walk down that same gravel road in summers to come, she will think it very dark, maybe the darkest place she has ever been.

And it is still dark at our lake cabin, just not as dark as it used to be. In that sense, it is the same as most anywhere people live. The places that are still primitively dark, such as the oceans, the Outback, the Amazon, are places most of us will never even visit-let alone inhabit. Their level of darkness is no longer our experience of night. In the urban areas where increasing numbers of us live-by 2050 some two-thirds of the world's human population-there is more and more artificial light, less and less natural darkness.

A good illustration of this new reality is that for most people living in cities around the world, our eyes seldom adjust from daylight to dark. Normally, as the world darkens, our eyes would shift to scotopic or "night-vision," moving from favoring "cones" (which show us the world in color) to favoring "rods" (which detect fainter light but not color). In natural conditions this happens over time-thirty minutes is good, a couple of hours better. But in a modern city flooded with artificial light, this rarely happens at all. This is why a gas lamp in a modern city seems ridiculously dim. But to a 19th-century city dweller, eyes adjusted to darkness, these lamps would have seemed impressively bright.

We live our nights swamped in a darkness diluted with artificial light. As a result, we mostly have no idea what we are missing, what we are losing. We have no idea what it's like to be out on a naturally dark night.

***

About twenty years ago, an amateur astronomer named John Bortle decided to make this clear. He had grown used to other astronomers-younger ones, especially-urging him to visit some star-gazing spot they described as "so dark!" only to find there what he had found everywhere, that this new location was not nearly as dark as his companions believed. In 2001, he published "the Bortle Dark-Sky Scale," which named nine levels of darkness. The scale begins at 9 (our brightest places-any of the world's cities, with rare exceptions) and progresses down to 1 (our darkest places, with no evidence of artificial light).

Ever since learning of Bortle's scale, I have been fascinated by the concept. But when I asked a National Park Service friend where I could experience "Bortle Scale 1," he laughed and suggested Australia. What about here in the US? Depending on whom you asked, he said, there were few if any places left in the lower 48 with that kind of darkness. When later I spent a night in Death Valley National Park with another Park Service friend, he told me that he had ranked the level of darkness in more than 200 NPS locations and named only three as Bortle Scale 1. Two of these he told me-"The Racetrack" in Death Valley, and a spot along the Green River in southern Utah-and the third he kept a secret.

Think of this. Bortle Scale 1 is natural darkness, night without artificial light-none on the horizon, none in the sky. It is night's darkness as it would have been for all of time before gas and then, especially, electric lighting. Which, for many rural places in the US, means until just a few decades ago. We have taken the natural state of things and-over the entire country-diminished it. We have introduced the artificial into the natural, and our experience of night is not what it was. We no longer experience the darkness that our ancestors-even, for many, our own grandparents-experienced.

Consider this too: on that scale of darkness, where 9 represents our lit-up cities and 1 this natural darkness, most Americans and Europeans and city-dwellers worldwide live in level 5 and above. That is, we rarely or never experience a night any darker than midway on the scale. So, our nights are not just a bit brighter than those who came before us knew, but a lot brighter.

Perhaps this makes sense in a city where we live immersed in artificial light. (Indeed, once you start seeing the lights, you see them all around.) But once we get away from urban areas? In satellite images the white city splotches seem surrounded by expanses of darkness. It looks as though once we get outside the cities we get back into the dark. Unfortunately, that's not the whole story.

In 2001, a group of Italian and American astronomers produced The World Atlas of the Artificial Night Sky Brightness. Using computer-generated color-coded images, they created a map of the world's light pollution. The US east of the Mississippi, northern Europe, Japan-wealthy, highly-populated areas of the Atlas bloomed with bright yellows, oranges, and reds bordered by fluorescent greens and blues, with cities around the world spotted white. Even into black oceans and seas did a gray buffer move from illuminated shores. As impressive as these images were when the Atlas was updated in 2016, the spread of light had gotten worse. Almost everywhere is growing brighter, the new map seemed to say, and almost nowhere is growing darker.

While the Bortle Scale gives us a way to talk about darkness in specific locations, the World Atlas gives us an overview of natural darkness around the world and just how rare it has become. On this map, nowhere in western Europe remains naturally dark. You would have to venture out into the seas to find that kind of darkness. The same is true of the lower 48 US states, where the map only natural darkness only in scraps and patches, and none east of the Great Plains.

These and other tools offer us ways to talk about light pollution's spread, but most of all they help us grasp something intangible: the diminishing darkness in our everyday experience of life. Darkness is the essential quality of night. With its diminishing, all the other qualities that make our experiences of a starry night-such as solitude, wildness, and mystery-are diminished as well.

"In a dark time," wrote Roethke, "the eye begins to see." He was focused on the figurative, but his words ring true of the literal as well. Only from our darkest places do we see the night's faintest lights.

"In a dark time/the eye begins to see." -Theodore Roethke, In a Dark Time

On the darkest night I have ever known I said goodbye to a friend and started walking back to my family's cabin. Between those points lay a hundred yards of dark woods, maybe the darkest they had ever been. It was a cloudy night with no moon or stars, and only a few lights around the lake. Seven years old, I walked slowly-eyes adjusting as they could, dry pine needles beneath my steps-until I made it about halfway, then stopped. I could no longer see the light from my neighbor's doorway and could not yet see the light from ours. I couldn't even see my hand before my face. The woods around me were filled with animals beginning to move, to use the cover of darkness to live. In the ground beneath me, in a constant dark, were the countless creatures that keep the forest soil alive. Above me, beyond the clouds, were layered blankets of stars. Inside me, amid the dark miracles of blood, muscle, and bone, my heart beat fast. But otherwise, I was alone. In this darkness I felt submerged, the presence pressing from all sides. I looked up past the pines to where, on a clear night, constellations would shine, but tonight a cloudy black wool came down to the treetops. Who knew what else this darkness might hold? When I caught brief sight through the pines of our cabin door's glow, I took off.

I ran down the one-lane road, sandy gravel kicked behind and didn't stop until I reached the light. I raced across the front yard-the same yard where for a lifetime I have stood in awe beneath the Milky Way-and didn't pause in leaving the dark behind.

I think of that darkness now, so many years later. Peppered with stars, washed by moonlight, the same natural darkness every night for all of time before that moment. I feel grateful to have known it as a child, to have such darkness a part of me that won't ever leave.

***

I want my daughter to know darkness like this. But the darkest place I have ever been, the darkness of my childhood, no longer exists. We are lucky, the place we have known—the lake (though not as clear) and woods (though splotched with more houses)—still more or less exists. But the darkness I knew then has faded. The ever-larger small towns to the northwest and south have made sure of that. There simply is more light on the horizon and overhead. And so, the night sky I knew as a child is gone because the darkness that held that sky is gone.

The term "shifting environmental baseline" describes how each new generation marks as reality the world as they experience it and the reality against which they will judge any change. But if that reality has been steadily diminished through the years, each new generation knows a living world less abundant and diverse than did those who came before. It's the idea that my two-year-old will never know the darkness I knew in these woods four decades ago, but when we walk down that same gravel road in summers to come, she will think it very dark, maybe the darkest place she has ever been.

And it is still dark at our lake cabin, just not as dark as it used to be. In that sense, it is the same as most anywhere people live. The places that are still primitively dark, such as the oceans, the Outback, the Amazon, are places most of us will never even visit-let alone inhabit. Their level of darkness is no longer our experience of night. In the urban areas where increasing numbers of us live-by 2050 some two-thirds of the world's human population-there is more and more artificial light, less and less natural darkness.

A good illustration of this new reality is that for most people living in cities around the world, our eyes seldom adjust from daylight to dark. Normally, as the world darkens, our eyes would shift to scotopic or "night-vision," moving from favoring "cones" (which show us the world in color) to favoring "rods" (which detect fainter light but not color). In natural conditions this happens over time-thirty minutes is good, a couple of hours better. But in a modern city flooded with artificial light, this rarely happens at all. This is why a gas lamp in a modern city seems ridiculously dim. But to a 19th-century city dweller, eyes adjusted to darkness, these lamps would have seemed impressively bright.

We live our nights swamped in a darkness diluted with artificial light. As a result, we mostly have no idea what we are missing, what we are losing. We have no idea what it's like to be out on a naturally dark night.

***

About twenty years ago, an amateur astronomer named John Bortle decided to make this clear. He had grown used to other astronomers-younger ones, especially-urging him to visit some star-gazing spot they described as "so dark!" only to find there what he had found everywhere, that this new location was not nearly as dark as his companions believed. In 2001, he published "the Bortle Dark-Sky Scale," which named nine levels of darkness. The scale begins at 9 (our brightest places-any of the world's cities, with rare exceptions) and progresses down to 1 (our darkest places, with no evidence of artificial light).

Ever since learning of Bortle's scale, I have been fascinated by the concept. But when I asked a National Park Service friend where I could experience "Bortle Scale 1," he laughed and suggested Australia. What about here in the US? Depending on whom you asked, he said, there were few if any places left in the lower 48 with that kind of darkness. When later I spent a night in Death Valley National Park with another Park Service friend, he told me that he had ranked the level of darkness in more than 200 NPS locations and named only three as Bortle Scale 1. Two of these he told me-"The Racetrack" in Death Valley, and a spot along the Green River in southern Utah-and the third he kept a secret.

Think of this. Bortle Scale 1 is natural darkness, night without artificial light-none on the horizon, none in the sky. It is night's darkness as it would have been for all of time before gas and then, especially, electric lighting. Which, for many rural places in the US, means until just a few decades ago. We have taken the natural state of things and-over the entire country-diminished it. We have introduced the artificial into the natural, and our experience of night is not what it was. We no longer experience the darkness that our ancestors-even, for many, our own grandparents-experienced.

Consider this too: on that scale of darkness, where 9 represents our lit-up cities and 1 this natural darkness, most Americans and Europeans and city-dwellers worldwide live in level 5 and above. That is, we rarely or never experience a night any darker than midway on the scale. So, our nights are not just a bit brighter than those who came before us knew, but a lot brighter.

Perhaps this makes sense in a city where we live immersed in artificial light. (Indeed, once you start seeing the lights, you see them all around.) But once we get away from urban areas? In satellite images the white city splotches seem surrounded by expanses of darkness. It looks as though once we get outside the cities we get back into the dark. Unfortunately, that's not the whole story.

In 2001, a group of Italian and American astronomers produced The World Atlas of the Artificial Night Sky Brightness. Using computer-generated color-coded images, they created a map of the world's light pollution. The US east of the Mississippi, northern Europe, Japan-wealthy, highly-populated areas of the Atlas bloomed with bright yellows, oranges, and reds bordered by fluorescent greens and blues, with cities around the world spotted white. Even into black oceans and seas did a gray buffer move from illuminated shores. As impressive as these images were when the Atlas was updated in 2016, the spread of light had gotten worse. Almost everywhere is growing brighter, the new map seemed to say, and almost nowhere is growing darker.

While the Bortle Scale gives us a way to talk about darkness in specific locations, the World Atlas gives us an overview of natural darkness around the world and just how rare it has become. On this map, nowhere in western Europe remains naturally dark. You would have to venture out into the seas to find that kind of darkness. The same is true of the lower 48 US states, where the map only natural darkness only in scraps and patches, and none east of the Great Plains.

These and other tools offer us ways to talk about light pollution's spread, but most of all they help us grasp something intangible: the diminishing darkness in our everyday experience of life. Darkness is the essential quality of night. With its diminishing, all the other qualities that make our experiences of a starry night-such as solitude, wildness, and mystery-are diminished as well.

"In a dark time," wrote Roethke, "the eye begins to see." He was focused on the figurative, but his words ring true of the literal as well. Only from our darkest places do we see the night's faintest lights.

Cuprins

Table of Contents

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Foreword: Karen Trevino

Foreword: Scott Slovic

1. Introduction

2. Darkness

3. Fear

4. Knowledge

5. Solace

6. Solitude

7. Moonlight

8. Wildness

9. Mystery

About the Author and Photographer

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Foreword: Karen Trevino

Foreword: Scott Slovic

1. Introduction

2. Darkness

3. Fear

4. Knowledge

5. Solace

6. Solitude

7. Moonlight

8. Wildness

9. Mystery

About the Author and Photographer

Descriere

Combining the lyrical writing from Paul Bogard with night-sky photography from Beau Rogers, To Know A Starry Night explores the powerful experience of being outside under a natural starry sky.