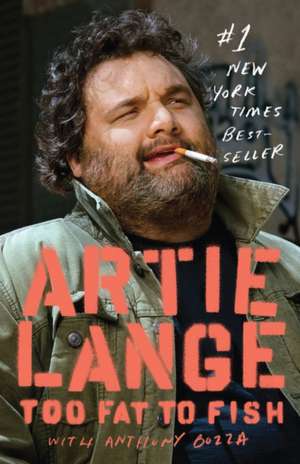

Too Fat to Fish

Autor Artie Lange Anthony Bozzaen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mai 2009

When Artie Lange joined the permanent cast of The Howard Stern Show in 2001, it was possibly the greatest thing ever to happen in the Stern universe, second only to the show’s move to the wild, uncensored frontier of satellite radio. Lange provided what Stern had yet to find all in the same place: a wit quick enough to keep pace with his own, a pathetic self-image to dwarf his own, a personal history both heartbreaking and hilarious, and an ingrained sense of self-sabotage that continually keeps things interesting.

A natural storyteller with a bottomless pit of material, Lange grew up in a close-knit, working-class Italian family in Union, New Jersey, a maniacal Yankees fan who pursued the two things his father said he was cut out for—sports and comedy. Tragically, Artie Lange Sr. never saw the truth in that prediction: He became a quadriplegic in an accident when Artie was eighteen and died soon after. But as with every trial in his life, from his drug addiction to his obesity to his fights with his mother, Artie mines the humor, pathos, and humanity in these events and turns them into comedy classics.

True fans of the Stern Show will find Artie gold in these pages: hilarious tales that couldn’t have happened to anyone else. There are stories from his days driving a Jersey cab, working as a longshoreman in Port Newark, and navigating the dark circuit of stand-up comedy. There are outrageous episodes from the frenzied heights of his coked-up days at MADtv, surprisingly moving stories from his childhood, and an account of his recent U.S.O. tour that is equally stirring and irreverent. But also in this volume are stories Artie’s never told before, including some that he deemed too revealing for radio.

Wild, shocking, and drop-dead hilarious, Too Fat to Fish is Artie Lange giving everything he’s got to give. And like a true pro, the man never disappoints.

Preț: 114.79 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 172

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.97€ • 23.49$ • 18.31£

21.97€ • 23.49$ • 18.31£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 27 martie-10 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780385526579

ISBN-10: 0385526571

Pagini: 306

Ilustrații: 16-PP COLOR PHOTO INSERT; B/W PHOTOS THROUGHOUT

Dimensiuni: 136 x 205 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Editura: Spiegel & Grau

ISBN-10: 0385526571

Pagini: 306

Ilustrații: 16-PP COLOR PHOTO INSERT; B/W PHOTOS THROUGHOUT

Dimensiuni: 136 x 205 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Editura: Spiegel & Grau

Extras

If my father’s trial was my first victory as a performer, then meeting Frankie Valli was my first run-in with one of my peers. I was about eighteen months old, so Frankie and I didn’t have much to talk about, but how we met is another shining example of just what kind of nut my father was. He was amazing–a legitimately crazy Newark street kid with brazen self-confidence and a wild sense of humor that our family and almost everyone we knew found incredibly endearing. There are all types of funny, and his type got you laughing and made you shake your head at just how fucking nuts he was, but you never lost sight of the fact that he meant his jokes, gags, and teasing in an affectionate way.

For those who don’t know, Frankie Valli and the Four Seasons were in the late ’50s and ’60s what Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band is to the post—baby boomer generation: The Four Seasons was the singing group for people living in New Jersey. Frankie Valli himself grew up in north Newark, in a housing project called the Stephen Crane Village, which was close to where both of my parents were from. My mother grew up just a couple of blocks away on North 7th Street, while my father lived a few miles away in south Newark. My mom and dad were born around the same year as Bob Dylan, but he was never their spokesman: The whole sixties folk scene and after it the hippie, Woodstock stuff didn’t really affect them at all. It wasn’t just that their upbringing was so different from that of the middle-class rich kids who “tuned in, turned on, and dropped out,” it was that they didn’t relate to the message at all.

The soundtrack of my parents’ young adulthood was simple and it never wavered: early rock and roll. And to them, Frankie Valli and the Four Seasons were the coolest group in the world. To this day, my mother still doesn’t like any of the boomer rock associated with her generation, aside from the Beatles, of course, which transcends all. She loves Chuck Berry, all things Motown, Bobby Darin, and all of the great fifties crooners. My father loved the same stuff, though for a brief period of time he grew his hair kind of long and listened to The Doors. I remember him singing “Roadhouse Blues” and “Light My Fire” really loud in the truck on his way to work. But it wasn’t any kind of statement other than that he liked the tunes.

The Frankie Valli mind-set was different; it embodied the values of the hardworking families from Newark and Union, who did everything they could to try to get a better life for their kids. It was the background music of their lives and it spoke about their lives, so it meant a lot to them. And because of that, especially among my Italian friends, it means a lot to us. The sound wasn’t current even when I was a kid, but Frankie Valli and the Four Seasons was something that bonded every Italian kid in Union to one another. It was like an unspoken thing, probably in the same way old Italian singers like Louis Prima had meaning for our parents because of their parents. There wasn’t a sense of rebelling against your parents’ music when it came to Frankie Valli–that would be like going against the family. And if there’s one thing all Italians know, it’s that you never, ever go against the family.

I don’t care what anybody says, it’s great music. When I was driving around with my friends, we could easily throw in a Frankie Valli tape and listen to it and really enjoy it. My buddy Mike Ciccone and I see eye to eye over this because in both of our houses growing up, Frankie and the Four Seasons was always on and our parents were always singing along. One night when we were about nineteen, we were out driving in Mike’s Mustang convertible with the radio tuned to CBS-FM, the great oldies station, when “Rag Doll” came on. We sat there enjoying the harmonies and Frankie’s amazingly high voice until the kids who were out with us, sitting in the backseat, interrupted our good time.

“What is this shit?” one of them said. “Get this shit off, put on PLJ!”

My buddy Ciccone was one of those guys who really did not take shit, at any time, from anybody. I will never forget how he calmly lowered the volume and looked over at me, and on cue, we said together: “Frankie Valli is fucking cool, man.” There was no way we were going to let anyone talk shit. The others could have gotten out and walked for all we cared.

Those two didn’t know what they were missing: The Four Seasons easily had thirty or forty Top Ten hit records. And now there’s the musical Jersey Boys, based on Frankie Valli’s life story. I have seen it three times now, and I am far from what you’d call a patron of the theater. Really, it is the only Broadway musical I could ever see myself sitting through, because, much like The Sopranos, it has what you need to keep me interested: a good story, Jersey references like crazy, and an amazing sound track. Anyway, in the late sixties, my father started his own business.

For years he had hung antennas, run wires, and repaired TVs for American Radio on Route 22 in Union. Once he was married and had a child (me), he took stock and decided he needed to make some changes. He was living with his wife and child in a small apartment on Reynolds Terrace in Orange, New Jersey, and like a guy in a Four Seasons song, my father wanted a better life. He decided to buy his own van and hustle as hard as he could to make it on his own. My dad was definitely a hard worker and an achiever, so he got that van, he worked his ass off, and, once he’d saved enough for a down payment, he bought us a house in the suburbs for thirty grand.

Status symbols were important to my father–like having the most expensive new car that he could reasonably afford and taking the family on a big vacation every summer. For two weeks, usually in August, we would go down to Wildwood Crest, New Jersey. We went to Wildwood each summer until I was about twelve, and I have so many good memories of those summers with my family that mean the world to me. In the summer of ’69, I was a few months away from turning two and my sister was just a few months old. My grandmother on my mother’s side, Grandma Caprio, stayed home with my sister to give my mom a bit of a break.

Off we went, down the Shore and headed for the Olympic Motel. The Olympic was fine, but it was definitely a motel, not a hotel–nothing too luxurious, just a place to stay right there on the ocean. (In later years we switched to the Crusader Motel.) Wildwood Crest was teeming with people from North Jersey and Philadelphia who’d come to have an old-fashioned good time on the beach. They wanted to play ball, get a nice bite to eat on the Wildwood boardwalk, which was home to some amazing cheesesteak restaurants, or nearby Seaside Heights, which also had great places for cheesesteak. Where you got your cheesesteaks was always a source of debate. In Seaside, there was Steaks Unlimited and Midway, which was a walk-up joint that used synthetic, welfarestyle cheese. That might sound disgusting, but let me tell you, when you’re drunk, five Midway cheesesteaks are just about the best thing in the world–that welfare cheese goes down real easy. While we’re on the subject, though, J.R.’s Cheesesteak and Steaks Unlimited are my favorites, and on the Wildwood Crest boardwalk I prefer the places that use real cheese–some even use mozzarella, which I have found to improve just about anything.

By the summer of ’69 my parents’ favorite band, the Four Seasons, had hit a bit of a dry patch after a tremendous run of six or seven years of hits. That creative lull happens to everyone at some point, but this was worse, because the music of the time was changing too, so they weren’t winning any new fans. Like so many groups of that era, they were forced to play much smaller venues. The week we happened to be in Wildwood, they were playing a five-night engagement at the Starlight Ballroom, which was a decent-sized venue, but nothing worth writing home about.

My mother and father really wanted to go see them, but they had no idea what they’d do with me for those few hours, so they kind of put it out of their minds. Or at least my mother did; my old man was not the type to be discouraged by anything. One afternoon as they were passing the front desk at the motel, they asked the clerk how to get to the Starlight because they’d heard Frankie Valli was playing. There are certain people in this world who somehow earn the trust of strangers without even trying because of the way they carry themselves. My father was one of them.

“I will give you a little hint,” the clerk said, leaning forward. “Frankie Valli is actually staying right here in the motel.”

“Really?” my mother said, smiling.

“What do you know?” my father said.

There are also certain people in this world who know how to capitalize on a situation regardless of odds or etiquette. My father was one of them too. Being a natural smooth talker, Pop was able to get the room number out of the guy. My father was charming enough that all he probably did was slip the guy a sawbuck. For all you pussies who don’t know what a sawbuck is, it’s a ten dollar bill.

We went up to the floor and passed by the room but didn’t see any action. The next day, we went back, and sure enough, as my father’s crazy luck would go, Frankie Valli’s door was ajar. My parents debated about what to do: knock and introduce themselves as fans or just wander in like they didn’t know he was there, pretending they were looking for someone else. Neither idea made sense to my father. He had a better one.

“Okay, here’s what we’re gonna do,” he told my mom. “That door is open just enough for Little Artie to crawl through. Let’s pretend he got away from us while we were walking down the hall, and he just went in there.”

“Absolutely not!” my mother half-shouted. “No, Artie, that is just crazy.”

“What’s he gonna say? It’s a kid coming in his room! That way we don’t look like two nuts camping outside of his room waiting to jump him or something. It’ll break the ice!”

“We are talking about a baby–how are you going to tell him to do that? No, we are not doing that,” my mom said.

“Oh yeah? Watch this.”

My father took one of my favorite toys and, over the sound of my mother’s protests, threw it inside Frankie Valli’s room.

“Oh Jesus, what have you done, Artie?” my mom said, shaking her head.

My father knew that I went just about anywhere that toy went, and sure enough, I crawled right in there after it. Then they sat there, out in the hall, waiting for something to happen.

“So what now?” my mother asked.

“Shh!” my father said. “He’s gonna come out here in a minute holding the baby, and he’s gonna look around and ask whose kid he is. And then we’re gonna meet him. We’ll get an autograph and maybe a picture, and that’s it, okay?”

Well, that didn’t happen. Five minutes went by, ten minutes, fifteen minutes. My mother, as any mother would, started to get really worried. My father kept reassuring her with statements like:

“What? You think Frankie Valli is actually a kidnapper now and he’s doing something crazy with him?”

“Who knows?” she said. “You don’t!” That’s how my mother would deal with him: She’d remind him that his version of a situation wasn’t the only possible scenario, and then follow up with about fifty-two completely logical alternatives. Typically, my father would have absolutely no answer for these.

In this case, she had plenty to work with:

“What if he was in the room with a girl?”

“There could be naked people in there!”

“He is a STAR! You have no idea what those people do in their hotel rooms!”

“There could be some shady character in there dividing up money.”

“He could be on drugs.”

“A million different illegal things could be happening in there, Artie! You don’t know!”

At these times my father would listen, usually rolling his eyes, for as long as he could stand it. Then he’d do something about it. In this case, he walked over to the door and pushed it open. He and my mother walked in slowly and didn’t see anything close to the Sodom and Gomorrah my mother had imagined. At first they didn’t see anything at all. Then they looked toward the bathroom, where the light was on and the door was open. And there I was, sitting on the sink in Frankie Valli’s bathroom, playing with my toy, with a big smile on my face. Next to me, in a robe, shaving, was Frankie Valli. He was amusing me with a blob of shaving cream.

“Okay, little man,” he was saying. “We’re gonna find your parents right after I’m done shaving, but I hope they’re not far, because I’m in a hurry, kid.”

As someone who has become a bit of a celebrity, if this were to happen to me, I would have called the FBI. But there was Frankie Valli, in his room, in a robe, shaving, when a toddler crawled in unannounced. And then the kid’s parents show up? I’m much too suspicious–that would be too much for me. But this was a different time, and my father had that crazy Newark mentality that Frankie Valli definitely recognized and I’m sure could relate to. I’ve made my mom tell this story so many times that I have to believe her when she swears that, as insane as it sounds, it was not an awkward moment.

“Oh, we’re really sorry,” my father said. “We were looking all over for him–thank you so much for taking care of him. We are really sorry he crawled in here.”

Frankie, from the beginning, was completely cordial and they started talking like it was no big deal that they were in his hotel room under the strangest possible pretenses. At some point in the conversation, my mother and father admitted that they were big fans.

“You know what?” Frankie said. “You want to come to one of the shows?”

“We’d love to!” my mother said. “We just can’t find a babysitter for our son.”

“Well, don’t worry about that,” Frankie said. “Bring him. We’ll leave him backstage with some of the girls we have on tour. He will be completely safe, I promise you. Just bring him along, and you’ll come with us. Why don’t you get everything you need and we’ll go down to the show in a few minutes.”

Just like that, my parents went from wondering if they’d even be able to get tickets to meeting Frankie in his room to attending the show as Frankie’s guests! And it wasn’t just for that night–Frankie invited them down to two or three shows. He saw that they were a young couple, in love but struggling with money, and he was very, very generous with them. One of the nights after the show he asked them to come out to dinner with him, the Four Seasons, and everyone else on the tour, and since they were all just people from Newark, my parents fit in just fine. Even though Frankie Valli and the band were hitting some hard times, they weren’t anything less than gracious and humble.

At some point, my parents and I were hanging out with Frankie and his crew, on the terrace at the motel. My father had bought a camera for my mom in the motel lobby, and she took a bunch of pictures. She got me, my father, and Frankie Valli, as well as a few of me alone with Frankie, and then my dad took a few of my mom and Frankie. Actually, my parents took pictures in every conceivable configuration of themselves, me, and Frankie Valli. Most of them were lost in the shuffle over the years, but for most of my childhood the best ones were proudly displayed in our house in Union in one of those square plastic picture cubes.

Talk about status symbols: Displaying a big plastic cube full of pictures of Frankie Valli in your home in North Jersey was like driving through the ghetto in a brand new Bentley. People would come over and pick up the thing and say, “Wow! How do you know Frankie Valli?”

“We’re friends with him,” my father would proudly say. “We were on vacation together there, down the Shore.”

The truth was, after that week, my parents completely lost touch with Frankie Valli and never saw him again. I asked my mother if they got Frankie’s contact information and tried to see him again, but she said no. She talked my dad into just being happy with the time they had had with Frankie there that week. She didn’t want to stay in touch and bug him, which in modern terms we call stalking.

My mother also wouldn’t ever have wanted Frankie to think they were taking advantage of his generosity.

They might not have spent time with him again, but they continued to watch Frankie’s career closely and remained big fans and supporters. When Jersey Boys opened on Broadway and Frankie was back in the news, I mentioned to Howard how I’d met him as a toddler and I had my mom dig out the one remaining picture we still have with him. It was up on the Stern Web site for a while, and now here it is, forever in print.

I’ve stared at this picture so many times over the years, because it shows my father in his heyday. He’s twenty-four or twenty-five years old, and as you can see, he looked like a movie star back then, my old man. He’s in great shape from climbing roofs, and there I

am, sitting on his knee, blond hair, dressed in all my little babyrabilia.

And there’s Frankie Valli looking at me, smiling, trying to make me laugh. I get so unbelievably emotional when I look at this that sometimes I just start to cry. That moment captures so much: It’s my family, it’s my father, and it’s Frankie Valli, a New Jersey hero who was to my father what Bruce Springsteen is to me. I’m there with my hero, meeting his hero. It’s hard for me to see myself as just a cute little kid, unaffected by life, without a care in the world. I had no idea then what I would later do to myself and my body as an adult.

When Jersey Boys opened in 2005, it became an instant success, taking in something like 400 grand in ticket sales in just one day. It’s still packing houses on Broadway, and it’s gone on to be a huge national touring production as well. As soon as I heard about it, I immediately got tickets to take my mother to see it for her birthday.

Four of us went: my mother; my beloved godmother, Aunt Dee, who is my mom’s younger sister Diane; my sister, Stacey; and me. I’ve seen it two more times since, and I assure you, it must be good for me to be recommending it here in my book. Did you think when you picked up this book that Artie Lange would be giving you tips on great Broadway musicals? Really, if you get a chance, see fucking Jersey Boys when you’re in town because it is the most fun you will ever have, whether you like the music or not.

All of that attention a few years ago put Frankie Valli back in the public eye again: He was on a few talk shows, he got a small role on The Sopranos, and he released an album covering love songs from the sixties. This was around 2006—2007, when The Stern Show was making the move over to satellite radio. One day Gary Dell’Abate, the show’s producer, came in and said to Howard during a break, “Would you like to have Frankie Valli in as a guest?” We’d just had Paul Anka on, who had delivered in such an amazing way–he really was one of the best guests we’d ever had. Howard did one of his classic, brilliant interviews, and Anka told great stories about Sinatra and the old days. People at the show had been on the fence about having him, but Anka blew other guests away. So when Frankie Valli came up, I stepped in.

“Oh man, that’d be great,” I said. “Look, you know, I got this great story about meeting him as a baby, and I could bring in the picture of me and him and see if it jars anything in his memory at all when we do the interview.Would it be all right if I had my mom up here to say hi to him in the greenroom after? She literally has not seen or talked to him in person since this week that she and my father and I spent with the Four Seasons at this motel in the summer of ’69.”

Howard, as anyone who’s met him or heard him in action knows, is always thinking–that guy’s mind is just incredibly quick.

“That would be great to do on the air if your mother agrees to it,” he said. “Let’s do it.”

I called my mom that afternoon, all excited to make this reunion happen. Now, my mother really hates being on camera and hates attention–in that way and so many other ways, she’s the complete opposite of me. It took some time and a lot of badgering, but eventually I convinced her to come up to the show that day and see what would happen. Then, of course, some shit luck went on and for whatever reason Gary wasn’t able to book Frankie. Then Frankie’s character on The Sopranos got whacked, so he wasn’t in the public eye anymore. But the musical is still going strong and I’m still holding out, hoping that one day Frankie Valli will come up and do The Stern Show and I’ll be able to reunite him with my mom. It’s sappy and odds are that he doesn’t remember a thing, but it would mean a lot to her and to me and to the memory of my dad to be able to stand there with him and show him that picture. It would be a special memory coming full circle. In my life, things like that are what I live for and what I look forward to. In the meantime, I’ve always got the musical.

From the Hardcover edition.

For those who don’t know, Frankie Valli and the Four Seasons were in the late ’50s and ’60s what Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band is to the post—baby boomer generation: The Four Seasons was the singing group for people living in New Jersey. Frankie Valli himself grew up in north Newark, in a housing project called the Stephen Crane Village, which was close to where both of my parents were from. My mother grew up just a couple of blocks away on North 7th Street, while my father lived a few miles away in south Newark. My mom and dad were born around the same year as Bob Dylan, but he was never their spokesman: The whole sixties folk scene and after it the hippie, Woodstock stuff didn’t really affect them at all. It wasn’t just that their upbringing was so different from that of the middle-class rich kids who “tuned in, turned on, and dropped out,” it was that they didn’t relate to the message at all.

The soundtrack of my parents’ young adulthood was simple and it never wavered: early rock and roll. And to them, Frankie Valli and the Four Seasons were the coolest group in the world. To this day, my mother still doesn’t like any of the boomer rock associated with her generation, aside from the Beatles, of course, which transcends all. She loves Chuck Berry, all things Motown, Bobby Darin, and all of the great fifties crooners. My father loved the same stuff, though for a brief period of time he grew his hair kind of long and listened to The Doors. I remember him singing “Roadhouse Blues” and “Light My Fire” really loud in the truck on his way to work. But it wasn’t any kind of statement other than that he liked the tunes.

The Frankie Valli mind-set was different; it embodied the values of the hardworking families from Newark and Union, who did everything they could to try to get a better life for their kids. It was the background music of their lives and it spoke about their lives, so it meant a lot to them. And because of that, especially among my Italian friends, it means a lot to us. The sound wasn’t current even when I was a kid, but Frankie Valli and the Four Seasons was something that bonded every Italian kid in Union to one another. It was like an unspoken thing, probably in the same way old Italian singers like Louis Prima had meaning for our parents because of their parents. There wasn’t a sense of rebelling against your parents’ music when it came to Frankie Valli–that would be like going against the family. And if there’s one thing all Italians know, it’s that you never, ever go against the family.

I don’t care what anybody says, it’s great music. When I was driving around with my friends, we could easily throw in a Frankie Valli tape and listen to it and really enjoy it. My buddy Mike Ciccone and I see eye to eye over this because in both of our houses growing up, Frankie and the Four Seasons was always on and our parents were always singing along. One night when we were about nineteen, we were out driving in Mike’s Mustang convertible with the radio tuned to CBS-FM, the great oldies station, when “Rag Doll” came on. We sat there enjoying the harmonies and Frankie’s amazingly high voice until the kids who were out with us, sitting in the backseat, interrupted our good time.

“What is this shit?” one of them said. “Get this shit off, put on PLJ!”

My buddy Ciccone was one of those guys who really did not take shit, at any time, from anybody. I will never forget how he calmly lowered the volume and looked over at me, and on cue, we said together: “Frankie Valli is fucking cool, man.” There was no way we were going to let anyone talk shit. The others could have gotten out and walked for all we cared.

Those two didn’t know what they were missing: The Four Seasons easily had thirty or forty Top Ten hit records. And now there’s the musical Jersey Boys, based on Frankie Valli’s life story. I have seen it three times now, and I am far from what you’d call a patron of the theater. Really, it is the only Broadway musical I could ever see myself sitting through, because, much like The Sopranos, it has what you need to keep me interested: a good story, Jersey references like crazy, and an amazing sound track. Anyway, in the late sixties, my father started his own business.

For years he had hung antennas, run wires, and repaired TVs for American Radio on Route 22 in Union. Once he was married and had a child (me), he took stock and decided he needed to make some changes. He was living with his wife and child in a small apartment on Reynolds Terrace in Orange, New Jersey, and like a guy in a Four Seasons song, my father wanted a better life. He decided to buy his own van and hustle as hard as he could to make it on his own. My dad was definitely a hard worker and an achiever, so he got that van, he worked his ass off, and, once he’d saved enough for a down payment, he bought us a house in the suburbs for thirty grand.

Status symbols were important to my father–like having the most expensive new car that he could reasonably afford and taking the family on a big vacation every summer. For two weeks, usually in August, we would go down to Wildwood Crest, New Jersey. We went to Wildwood each summer until I was about twelve, and I have so many good memories of those summers with my family that mean the world to me. In the summer of ’69, I was a few months away from turning two and my sister was just a few months old. My grandmother on my mother’s side, Grandma Caprio, stayed home with my sister to give my mom a bit of a break.

Off we went, down the Shore and headed for the Olympic Motel. The Olympic was fine, but it was definitely a motel, not a hotel–nothing too luxurious, just a place to stay right there on the ocean. (In later years we switched to the Crusader Motel.) Wildwood Crest was teeming with people from North Jersey and Philadelphia who’d come to have an old-fashioned good time on the beach. They wanted to play ball, get a nice bite to eat on the Wildwood boardwalk, which was home to some amazing cheesesteak restaurants, or nearby Seaside Heights, which also had great places for cheesesteak. Where you got your cheesesteaks was always a source of debate. In Seaside, there was Steaks Unlimited and Midway, which was a walk-up joint that used synthetic, welfarestyle cheese. That might sound disgusting, but let me tell you, when you’re drunk, five Midway cheesesteaks are just about the best thing in the world–that welfare cheese goes down real easy. While we’re on the subject, though, J.R.’s Cheesesteak and Steaks Unlimited are my favorites, and on the Wildwood Crest boardwalk I prefer the places that use real cheese–some even use mozzarella, which I have found to improve just about anything.

By the summer of ’69 my parents’ favorite band, the Four Seasons, had hit a bit of a dry patch after a tremendous run of six or seven years of hits. That creative lull happens to everyone at some point, but this was worse, because the music of the time was changing too, so they weren’t winning any new fans. Like so many groups of that era, they were forced to play much smaller venues. The week we happened to be in Wildwood, they were playing a five-night engagement at the Starlight Ballroom, which was a decent-sized venue, but nothing worth writing home about.

My mother and father really wanted to go see them, but they had no idea what they’d do with me for those few hours, so they kind of put it out of their minds. Or at least my mother did; my old man was not the type to be discouraged by anything. One afternoon as they were passing the front desk at the motel, they asked the clerk how to get to the Starlight because they’d heard Frankie Valli was playing. There are certain people in this world who somehow earn the trust of strangers without even trying because of the way they carry themselves. My father was one of them.

“I will give you a little hint,” the clerk said, leaning forward. “Frankie Valli is actually staying right here in the motel.”

“Really?” my mother said, smiling.

“What do you know?” my father said.

There are also certain people in this world who know how to capitalize on a situation regardless of odds or etiquette. My father was one of them too. Being a natural smooth talker, Pop was able to get the room number out of the guy. My father was charming enough that all he probably did was slip the guy a sawbuck. For all you pussies who don’t know what a sawbuck is, it’s a ten dollar bill.

We went up to the floor and passed by the room but didn’t see any action. The next day, we went back, and sure enough, as my father’s crazy luck would go, Frankie Valli’s door was ajar. My parents debated about what to do: knock and introduce themselves as fans or just wander in like they didn’t know he was there, pretending they were looking for someone else. Neither idea made sense to my father. He had a better one.

“Okay, here’s what we’re gonna do,” he told my mom. “That door is open just enough for Little Artie to crawl through. Let’s pretend he got away from us while we were walking down the hall, and he just went in there.”

“Absolutely not!” my mother half-shouted. “No, Artie, that is just crazy.”

“What’s he gonna say? It’s a kid coming in his room! That way we don’t look like two nuts camping outside of his room waiting to jump him or something. It’ll break the ice!”

“We are talking about a baby–how are you going to tell him to do that? No, we are not doing that,” my mom said.

“Oh yeah? Watch this.”

My father took one of my favorite toys and, over the sound of my mother’s protests, threw it inside Frankie Valli’s room.

“Oh Jesus, what have you done, Artie?” my mom said, shaking her head.

My father knew that I went just about anywhere that toy went, and sure enough, I crawled right in there after it. Then they sat there, out in the hall, waiting for something to happen.

“So what now?” my mother asked.

“Shh!” my father said. “He’s gonna come out here in a minute holding the baby, and he’s gonna look around and ask whose kid he is. And then we’re gonna meet him. We’ll get an autograph and maybe a picture, and that’s it, okay?”

Well, that didn’t happen. Five minutes went by, ten minutes, fifteen minutes. My mother, as any mother would, started to get really worried. My father kept reassuring her with statements like:

“What? You think Frankie Valli is actually a kidnapper now and he’s doing something crazy with him?”

“Who knows?” she said. “You don’t!” That’s how my mother would deal with him: She’d remind him that his version of a situation wasn’t the only possible scenario, and then follow up with about fifty-two completely logical alternatives. Typically, my father would have absolutely no answer for these.

In this case, she had plenty to work with:

“What if he was in the room with a girl?”

“There could be naked people in there!”

“He is a STAR! You have no idea what those people do in their hotel rooms!”

“There could be some shady character in there dividing up money.”

“He could be on drugs.”

“A million different illegal things could be happening in there, Artie! You don’t know!”

At these times my father would listen, usually rolling his eyes, for as long as he could stand it. Then he’d do something about it. In this case, he walked over to the door and pushed it open. He and my mother walked in slowly and didn’t see anything close to the Sodom and Gomorrah my mother had imagined. At first they didn’t see anything at all. Then they looked toward the bathroom, where the light was on and the door was open. And there I was, sitting on the sink in Frankie Valli’s bathroom, playing with my toy, with a big smile on my face. Next to me, in a robe, shaving, was Frankie Valli. He was amusing me with a blob of shaving cream.

“Okay, little man,” he was saying. “We’re gonna find your parents right after I’m done shaving, but I hope they’re not far, because I’m in a hurry, kid.”

As someone who has become a bit of a celebrity, if this were to happen to me, I would have called the FBI. But there was Frankie Valli, in his room, in a robe, shaving, when a toddler crawled in unannounced. And then the kid’s parents show up? I’m much too suspicious–that would be too much for me. But this was a different time, and my father had that crazy Newark mentality that Frankie Valli definitely recognized and I’m sure could relate to. I’ve made my mom tell this story so many times that I have to believe her when she swears that, as insane as it sounds, it was not an awkward moment.

“Oh, we’re really sorry,” my father said. “We were looking all over for him–thank you so much for taking care of him. We are really sorry he crawled in here.”

Frankie, from the beginning, was completely cordial and they started talking like it was no big deal that they were in his hotel room under the strangest possible pretenses. At some point in the conversation, my mother and father admitted that they were big fans.

“You know what?” Frankie said. “You want to come to one of the shows?”

“We’d love to!” my mother said. “We just can’t find a babysitter for our son.”

“Well, don’t worry about that,” Frankie said. “Bring him. We’ll leave him backstage with some of the girls we have on tour. He will be completely safe, I promise you. Just bring him along, and you’ll come with us. Why don’t you get everything you need and we’ll go down to the show in a few minutes.”

Just like that, my parents went from wondering if they’d even be able to get tickets to meeting Frankie in his room to attending the show as Frankie’s guests! And it wasn’t just for that night–Frankie invited them down to two or three shows. He saw that they were a young couple, in love but struggling with money, and he was very, very generous with them. One of the nights after the show he asked them to come out to dinner with him, the Four Seasons, and everyone else on the tour, and since they were all just people from Newark, my parents fit in just fine. Even though Frankie Valli and the band were hitting some hard times, they weren’t anything less than gracious and humble.

At some point, my parents and I were hanging out with Frankie and his crew, on the terrace at the motel. My father had bought a camera for my mom in the motel lobby, and she took a bunch of pictures. She got me, my father, and Frankie Valli, as well as a few of me alone with Frankie, and then my dad took a few of my mom and Frankie. Actually, my parents took pictures in every conceivable configuration of themselves, me, and Frankie Valli. Most of them were lost in the shuffle over the years, but for most of my childhood the best ones were proudly displayed in our house in Union in one of those square plastic picture cubes.

Talk about status symbols: Displaying a big plastic cube full of pictures of Frankie Valli in your home in North Jersey was like driving through the ghetto in a brand new Bentley. People would come over and pick up the thing and say, “Wow! How do you know Frankie Valli?”

“We’re friends with him,” my father would proudly say. “We were on vacation together there, down the Shore.”

The truth was, after that week, my parents completely lost touch with Frankie Valli and never saw him again. I asked my mother if they got Frankie’s contact information and tried to see him again, but she said no. She talked my dad into just being happy with the time they had had with Frankie there that week. She didn’t want to stay in touch and bug him, which in modern terms we call stalking.

My mother also wouldn’t ever have wanted Frankie to think they were taking advantage of his generosity.

They might not have spent time with him again, but they continued to watch Frankie’s career closely and remained big fans and supporters. When Jersey Boys opened on Broadway and Frankie was back in the news, I mentioned to Howard how I’d met him as a toddler and I had my mom dig out the one remaining picture we still have with him. It was up on the Stern Web site for a while, and now here it is, forever in print.

I’ve stared at this picture so many times over the years, because it shows my father in his heyday. He’s twenty-four or twenty-five years old, and as you can see, he looked like a movie star back then, my old man. He’s in great shape from climbing roofs, and there I

am, sitting on his knee, blond hair, dressed in all my little babyrabilia.

And there’s Frankie Valli looking at me, smiling, trying to make me laugh. I get so unbelievably emotional when I look at this that sometimes I just start to cry. That moment captures so much: It’s my family, it’s my father, and it’s Frankie Valli, a New Jersey hero who was to my father what Bruce Springsteen is to me. I’m there with my hero, meeting his hero. It’s hard for me to see myself as just a cute little kid, unaffected by life, without a care in the world. I had no idea then what I would later do to myself and my body as an adult.

When Jersey Boys opened in 2005, it became an instant success, taking in something like 400 grand in ticket sales in just one day. It’s still packing houses on Broadway, and it’s gone on to be a huge national touring production as well. As soon as I heard about it, I immediately got tickets to take my mother to see it for her birthday.

Four of us went: my mother; my beloved godmother, Aunt Dee, who is my mom’s younger sister Diane; my sister, Stacey; and me. I’ve seen it two more times since, and I assure you, it must be good for me to be recommending it here in my book. Did you think when you picked up this book that Artie Lange would be giving you tips on great Broadway musicals? Really, if you get a chance, see fucking Jersey Boys when you’re in town because it is the most fun you will ever have, whether you like the music or not.

All of that attention a few years ago put Frankie Valli back in the public eye again: He was on a few talk shows, he got a small role on The Sopranos, and he released an album covering love songs from the sixties. This was around 2006—2007, when The Stern Show was making the move over to satellite radio. One day Gary Dell’Abate, the show’s producer, came in and said to Howard during a break, “Would you like to have Frankie Valli in as a guest?” We’d just had Paul Anka on, who had delivered in such an amazing way–he really was one of the best guests we’d ever had. Howard did one of his classic, brilliant interviews, and Anka told great stories about Sinatra and the old days. People at the show had been on the fence about having him, but Anka blew other guests away. So when Frankie Valli came up, I stepped in.

“Oh man, that’d be great,” I said. “Look, you know, I got this great story about meeting him as a baby, and I could bring in the picture of me and him and see if it jars anything in his memory at all when we do the interview.Would it be all right if I had my mom up here to say hi to him in the greenroom after? She literally has not seen or talked to him in person since this week that she and my father and I spent with the Four Seasons at this motel in the summer of ’69.”

Howard, as anyone who’s met him or heard him in action knows, is always thinking–that guy’s mind is just incredibly quick.

“That would be great to do on the air if your mother agrees to it,” he said. “Let’s do it.”

I called my mom that afternoon, all excited to make this reunion happen. Now, my mother really hates being on camera and hates attention–in that way and so many other ways, she’s the complete opposite of me. It took some time and a lot of badgering, but eventually I convinced her to come up to the show that day and see what would happen. Then, of course, some shit luck went on and for whatever reason Gary wasn’t able to book Frankie. Then Frankie’s character on The Sopranos got whacked, so he wasn’t in the public eye anymore. But the musical is still going strong and I’m still holding out, hoping that one day Frankie Valli will come up and do The Stern Show and I’ll be able to reunite him with my mom. It’s sappy and odds are that he doesn’t remember a thing, but it would mean a lot to her and to me and to the memory of my dad to be able to stand there with him and show him that picture. It would be a special memory coming full circle. In my life, things like that are what I live for and what I look forward to. In the meantime, I’ve always got the musical.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Compulsively readable . . . this debut memoir from the comedian best known as Howard Stern’s radio show sidekick is scrappy, funny, tumultuous and profane.”—Publishers Weekly