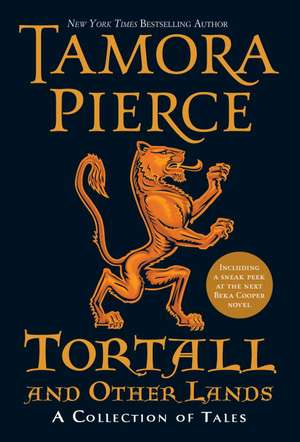

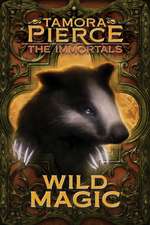

Tortall and Other Lands: A Collection of Tales

Autor Tamora Pierceen Limba Engleză Hardback – 31 ian 2011 – vârsta de la 12 ani

Preț: 120.91 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 181

Preț estimativ în valută:

23.14€ • 24.74$ • 19.29£

23.14€ • 24.74$ • 19.29£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780375866760

ISBN-10: 0375866760

Pagini: 369

Dimensiuni: 151 x 214 x 32 mm

Greutate: 0.51 kg

Editura: Random House Books for Young Readers

ISBN-10: 0375866760

Pagini: 369

Dimensiuni: 151 x 214 x 32 mm

Greutate: 0.51 kg

Editura: Random House Books for Young Readers

Notă biografică

New York Times bestselling writer Tamora Pierce captured the imagination of readers more than 20 years ago with Alanna: The First Adventure. She has written 16 books about the extraordinary kingdom of Tortall, with another to come in fall 2011. She lives in upstate New York, with her husband and an assortment of wildlife.

Extras

Student of Ostriches

My story began as my mother carried me in her belly to the great Nawolu trade fair. Because she was pregnant, our tribe let Mama ride high on the back of our finest camel, which meant she was also lookout for our caravan. It was she who spotted the lion and gave the warning. Our warriors closed in tight around our people to keep them safe, but they were in no danger from the lion.

He was a young male, with no lionesses to guard him as he stalked a young ostrich who strayed from its parents. He drew closer to his intended prey. Its mama and papa raced toward the lion, faster than horses, their large eyes fixed on the threat. The lion was young and ignorant. He snarled as one ostrich kicked him. Then the other did the same. On and on the ostriches kicked the lion until he was a fur sack of bones.

As the ostriches led their children away, my mama said, she felt me kick in her belly for the first time.

If the kicking ostriches were a good omen for our family, they were not for my papa. Two months later he was wounded in the leg in a battle with an enemy tribe. It never healed completely, forcing him to leave the ranks of the warriors and join the ranks of the wood-carvers, though he never complained. Not long after my papa began to walk with a cane, I was born. Papa was sad for a little while, because I was a girl. He would have liked a son to take his place as a warrior, but he always said that when I first smiled at him, he could not be sad anymore.

When I was six years old, I asked my parents if I could learn to go outside the village wall with the animal herds. Who could be happy inside the walls when the world lay outside? My parents spoke to our chief, who agreed that I could learn to watch goats on the rocky edges of the great plains on which the world was born.

Of course, I did not begin alone. My ten-year-old cousin Ogin was appointed to teach me. On that first morning I followed him and his dogs to a grazing place. Once the goats were settled, I asked him, “What must I learn?”

“First, you learn to use the herder’s weapon, the sling,” Ogin said. He was very tall and lean, like a stick with muscles. “You must be able to help the dogs drive off enemies.” He held up a strip of leather.

I practiced the twirl and the release of the stone in the sling until my shoulders were sore. For a change of pace, Ogin taught me the words to name the goats’ marks and parts until I knew them by heart. Once my muscles were relaxed again, I would take up the sling once more.

When it was time to eat our noon food, my cousin took the goats, the dogs, and me up onto a rock outcropping. From there we could see the plain stretch out before us under its veil of dusty air. This was my reward, this long view of the first step to the world. I almost forgot how to eat. Lonely trees fanned their branches out in flat-topped sprays. Vultures roosted in their branches. Veils of tall grass separated the herds of zebra, wildebeest, and gazelle in the distance. Lions waited near a watering hole close to our rocks as giraffes nibbled the leaves of thorny trees on the other side.

Watching it all, I saw movement. I gasped. “Ogin—there! Are those—are they ostriches?”

“You think, because your mama saw them, they are cousins to you?” he teased me. “What is it, Kylaia? Will you grow tail feathers and race them?”

The ostriches were running. They had long, powerful legs. When they ran, they opened their legs up and stretched. They were not delicate like the gazelle, like my older sisters. They ran in long, loping strides. Watching them, I thought, I want to run like that.

For a year I was Ogin’s apprentice. He taught me to keep the goats moving in the lands around the stone lookout place, so there would be grass throughout the year. He was patient and he did not laugh at me as I struggled to learn to be a dead shot with a sling, a careful tracker, and one who understood the ways of the dogs, the goats, and the wild creatures of the plains.

Ogin taught me to run, too, as he and my sisters did, like gazelles, on the balls of their feet. After our noon meals, as Ogin napped, I would practice my ostrich running. I opened up my strides, dug in my feet, and thrust out my chest, imagining myself to be a great bird, eating the ground with my big feet. Each day I ran a little farther and a little faster as Ogin and the dogs slept, and the goats and the birds looked on.

When I had followed Ogin for a year, my uncle the herd chief came out with us. Ogin made me show off my skills with the goats and the dogs.

“Tomorrow morning, come to me,” said my uncle. “You shall have a herd and dogs of your own.”

It was my seventh birthday. I was so proud! I was now a true member of the village with proper work to do. Papa gave me a wooden ball painted with colored stripes. Mama and my sisters had woven me new clothes and a cape for the cold. I ran through the village to show off my ball and to tell my friends that I was now a true worker.

My story began as my mother carried me in her belly to the great Nawolu trade fair. Because she was pregnant, our tribe let Mama ride high on the back of our finest camel, which meant she was also lookout for our caravan. It was she who spotted the lion and gave the warning. Our warriors closed in tight around our people to keep them safe, but they were in no danger from the lion.

He was a young male, with no lionesses to guard him as he stalked a young ostrich who strayed from its parents. He drew closer to his intended prey. Its mama and papa raced toward the lion, faster than horses, their large eyes fixed on the threat. The lion was young and ignorant. He snarled as one ostrich kicked him. Then the other did the same. On and on the ostriches kicked the lion until he was a fur sack of bones.

As the ostriches led their children away, my mama said, she felt me kick in her belly for the first time.

If the kicking ostriches were a good omen for our family, they were not for my papa. Two months later he was wounded in the leg in a battle with an enemy tribe. It never healed completely, forcing him to leave the ranks of the warriors and join the ranks of the wood-carvers, though he never complained. Not long after my papa began to walk with a cane, I was born. Papa was sad for a little while, because I was a girl. He would have liked a son to take his place as a warrior, but he always said that when I first smiled at him, he could not be sad anymore.

When I was six years old, I asked my parents if I could learn to go outside the village wall with the animal herds. Who could be happy inside the walls when the world lay outside? My parents spoke to our chief, who agreed that I could learn to watch goats on the rocky edges of the great plains on which the world was born.

Of course, I did not begin alone. My ten-year-old cousin Ogin was appointed to teach me. On that first morning I followed him and his dogs to a grazing place. Once the goats were settled, I asked him, “What must I learn?”

“First, you learn to use the herder’s weapon, the sling,” Ogin said. He was very tall and lean, like a stick with muscles. “You must be able to help the dogs drive off enemies.” He held up a strip of leather.

I practiced the twirl and the release of the stone in the sling until my shoulders were sore. For a change of pace, Ogin taught me the words to name the goats’ marks and parts until I knew them by heart. Once my muscles were relaxed again, I would take up the sling once more.

When it was time to eat our noon food, my cousin took the goats, the dogs, and me up onto a rock outcropping. From there we could see the plain stretch out before us under its veil of dusty air. This was my reward, this long view of the first step to the world. I almost forgot how to eat. Lonely trees fanned their branches out in flat-topped sprays. Vultures roosted in their branches. Veils of tall grass separated the herds of zebra, wildebeest, and gazelle in the distance. Lions waited near a watering hole close to our rocks as giraffes nibbled the leaves of thorny trees on the other side.

Watching it all, I saw movement. I gasped. “Ogin—there! Are those—are they ostriches?”

“You think, because your mama saw them, they are cousins to you?” he teased me. “What is it, Kylaia? Will you grow tail feathers and race them?”

The ostriches were running. They had long, powerful legs. When they ran, they opened their legs up and stretched. They were not delicate like the gazelle, like my older sisters. They ran in long, loping strides. Watching them, I thought, I want to run like that.

For a year I was Ogin’s apprentice. He taught me to keep the goats moving in the lands around the stone lookout place, so there would be grass throughout the year. He was patient and he did not laugh at me as I struggled to learn to be a dead shot with a sling, a careful tracker, and one who understood the ways of the dogs, the goats, and the wild creatures of the plains.

Ogin taught me to run, too, as he and my sisters did, like gazelles, on the balls of their feet. After our noon meals, as Ogin napped, I would practice my ostrich running. I opened up my strides, dug in my feet, and thrust out my chest, imagining myself to be a great bird, eating the ground with my big feet. Each day I ran a little farther and a little faster as Ogin and the dogs slept, and the goats and the birds looked on.

When I had followed Ogin for a year, my uncle the herd chief came out with us. Ogin made me show off my skills with the goats and the dogs.

“Tomorrow morning, come to me,” said my uncle. “You shall have a herd and dogs of your own.”

It was my seventh birthday. I was so proud! I was now a true member of the village with proper work to do. Papa gave me a wooden ball painted with colored stripes. Mama and my sisters had woven me new clothes and a cape for the cold. I ran through the village to show off my ball and to tell my friends that I was now a true worker.

Descriere

Collected here for the first time are all of the tales from the land of Tortall, featuring both previously unknown characters as well as old friends.