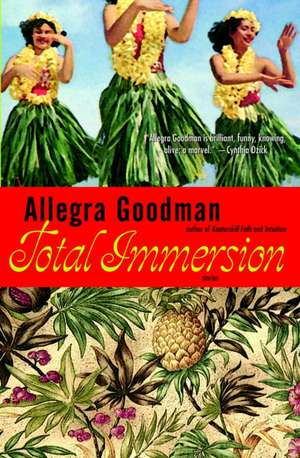

Total Immersion

Autor Allegra Goodmanen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 iul 1998

Total Immersion

In these and other exquisite stories, Allegra Goodman fills rooms with laughter and voices, captures dinner parties, seaside picnics, academic grudges, shul politics, and the kind of hurts that only families and lovers can know. Featuring two new stories previously published in The New Yorker, Total Immersion is Allegra Goodman's first collection of short fiction—a masterful work from one of the most powerful and eloquent voices on the American literary landscape.

Preț: 121.63 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 182

Preț estimativ în valută:

23.27€ • 24.36$ • 19.37£

23.27€ • 24.36$ • 19.37£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 10-24 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780385332996

ISBN-10: 0385332998

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 133 x 203 x 21 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Dial Press

ISBN-10: 0385332998

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 133 x 203 x 21 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Dial Press

Notă biografică

Allegra Goodman’s novels includeThe Chalk Artist, Intuition, The Cookbook Collector, Paradise Park,andKaaterskill Falls(a National Book Award finalist).Her fiction has appeared inThe New Yorker, Commentary, andPloughsharesand has been anthologized inThe O. Henry AwardsandBest American Short Stories.She has written two collections of short stories,The Family MarkowitzandTotal Immersionand a novel for younger readers,The Other Side of the Island.Her essays and reviews have appeared inThe New York Times Book Review, The Wall Street Journal, The New Republic, The Boston Globe, The Jewish Review of Books, andThe American Scholar.Raised in Honolulu, Goodman studied English and philosophy at Harvard and received a PhD in English literature from Stanford. She is the recipient of a Whiting Writer’s Award, the Salon Award for Fiction, and a fellowship from the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced study. She lives with her family in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where she is writing a new novel.

Extras

Onionskin

Dr. Friedell,

This is to apologize if I offended you in class a few weeks ago, though I realize you probably forgot the whole thing by now. I was the one who stood up and said "Fuck Augustine." What I meant was I didn't take the class to read him, I took it to learn about religion--God, prayer, ritual, the Madonna mother-goddess figure, forgiveness, miracles, sin, abortion, death, the big moral concepts. Because obviously I am not eighteen and I work, so school is not an academic exercise for me, and not just me, as I'm sure you'd realize if you looked around the room one of these days and saw there are thirty- and forty-year-olds and some a lot older than you are in the class--the point is, when you've been through marriage, kids, jobs, welfare, and the whole gamut and you come back to school you're ready for the real thing, and as far as I'm concerned Augustine's Conception of the Soul or whatever is not it. What is "it"? you're asking--well, that's what I came to find out, so you tell me. Obviously what you are paid for is to deal with the big religious issues and you are not dealing with them, which is what I was trying to point out when I made that remark in class, which I apologize for tone-wise but not for my feelings behind it.

My feelings still are that basically as a "mature student" I was supposed to feel grateful that the University of Hawaii let me in or gave me a second chance on life or whatever, like I am the lowly unwashed and I should come in the gates to be blessed by the big phallus. Or I am a housewife coming "back" to "school" driving my white Isuzu and eating my curds and whey. Look, I didn't come to salivate at your office door. You like to make distinctions, so you should make distinctions between you the employee and me the customer. You're the guy behind the counter.

Can I take a guess at what you're thinking?--"Another crazed woman in my class anti the educational system." But I'm not, I'm putting everything I've got on the line for religion.

Because the thing is that after I walked out on your class I sat down by the sausage trees near Moore Hall and I started watching the undergrads walking by in their Bermuda shorts going to lunch without a thought in their heads. I felt bad because for some reason I sort of believed in the universe part of university, that it was all about Life and Time and God, and Freedom, and when I got back in it was just so male and linear and there wasn't any magic in the religion classes, it was all a construct--the angels were symbols and the miracles were just things in nature. So I got up and took all my books to the bookstore and sold them back (for less than half what I paid for them) and I went home--a room in a termite palace. As I was saying before, I felt really bad because I think you might have the wrong idea about me--you probably don't know how into school I really was. I originally dropped out of Simmons in 1974 for a lot of reasons, my father died for one thing, but basically because I didn't see myself in school at that time in my life. The only thing I could really see myself doing was folk dancing--I was in the original core Israeli folk-dancing group at MIT, which you probably have never even heard of, but it's actually nationally famous--it's almost like the model for all the other clubs in the country. I spent those "college" years living in Brighton and dancing. When I say dancing I'm talking about a way of life--I knew over two hundred dances and I also did Balkan. We would get over to MIT and dance straight from 8:30 to 11 p.m., steaming into Walker Gym straight from the snow to sweat like you would not believe. We stripped down every night from coats, sweaters, and boots to tank tops, gauze skirts, bare feet, and cutoffs, and when we left we were so hot we carried our parkas under our arms. I actually knew a lot of the key people in the folk scene and performed in New York at some of the big festivals. So that was kind of my "schooling." I was a secretary--actually for two years I temped, we were all menial slaves in the folk club, with a few graduate students and programmers sprinkled in. At the time I was in a relationship with one of them, which is how I ended up going to Hawaii--he had an upgrade deal. After a week he freaked out and took off for Fiji, and I was stranded at a fleabag joint in Waikiki with about twenty-two dollars to my name and the room bill.

When he took off I sold my return ticket and got a job busing tables at Zippy's, then I worked in the kitchen doing prep, then I worked in the find-a-pearl oyster stand in the International Marketplace, then I sold gold electroplated cockroaches when they were in, then I sold paraphernalia and sex toys in back where Oriental Imports used to be, behind The Stop Light and the bikini store on King Street, then after that place folded I got a job in Crack Seed World, then I landed a job in luggage at Shirokya, worked at Longs Drugs checkout, and did inventory at The Good Earth. I was thinking about going back to Boston. Thinking a lot, Dr. Friedell--it was happening at an underground level. I realize you aren't interested in what kind of thinking a student who walks out of Augustine is experiencing, because you can't think about anything that hasn't been totally hashed out already by geniuses--that's the impression you give me anyway, all that stuff about us living on the last mushroom of the dunghill of Romanticism and standing on the shoulders of giants, and all you can do when you go back to school is learn how to use the library and document everything. Why do they make such a big deal about plagiarism if it's all been said already? Not that I think you're actually reading this, since it's written on onionskin in ball-point when you only accept typed stuff.

While I was working those different jobs I taught folk dancing at Kaimuki Y (once) and the temple (five x). I went to a Hebrew class at the temple because I was teaching all these dances to Israeli music and I didn't know Hebrew, but every time we would get past the alphabet some new guy or some kid would come into the class and we had to learn the alphabet again, so I never got beyond the letters. A total joke. Rabbi Siegel up at the temple used to go on these digressions, so obviously we never got anywhere, and finally after class I went up and said, "Rabbi, aren't we all just wasting time in here?"

He looks at me under the fluorescent lights in the Learning Center, which is all white linoleum and woodgrain tables and green plastic chairs, and nailed up on the walls all the Old World stuff, those ticky-tacky pictures of the bearded men. Rabbi Siegel faces me in his suit with his silver tie pin. "Sharon," he says, "I'm sorry you feel that way."

"I want to learn Hebrew," I said. "Isn't that what we're here for?"

"Sharon, I think you realize that in the end the words are the least important aspect of what I'm trying to teach. Come here," he says, pushing me into the sanctuary. He was one of those big-time formal rabbis who wore black robes at services and had like a whole set of hand signals for the organist--I think he was a frustrated conductor or actor. We go into the sanctuary and he flicks on the lights, floodlighting the temple ceiling, stained glass, et cetera. "Sharon," he says, "Judaism is more than a few simple phrases. It's a culture, one of music & art, poetry & light, it is the intimate & the sublime, exalted &"--I forget the exact words. "Think of the lyric music of the Psalms," he tells me. "While the Egyptians were building tombs we were singing of life and love, while the monuments of the ancients were crumbling to dust we were treading over the ruins in a tradition that arced back over the millennia and forward to the future. Our friends in class may never remember a word of Hebrew, but if they can sense something of the grandeur of our tradition the historic sweep of the epic blah blah blah chosen people."

I guess I sort of gave him a look, because this chosen-people crap was always one of my big problems with organized religion.

He heaves a big sigh, folds his arms over his belly. "I think you know how strongly I feel about that one," he says. "Each people is dear to God in its own way, and I often make the analogy to the different states of the Union." He was a great guy, Siegel, but when you asked him a question it was like throwing a bottle in the ocean and just watching it drift away over all his metaphors and comparisons plus the incidents it reminded him of. And as far as where I was coming from in the folk movement, he hadn't a clue because he was into "High" art, which goes back to what I was saying about the past. Siegel used to say "When I say the Bor'chu--"Bless ye the Lord'--I think how fitting a trumpet fanfare would be right there."

Meanwhile I was getting really alienated, not so much by him but by life in general, and by the kind of things I was doing, and I sort of disappeared for a while on Molokai with a guy I was having a relationship with at the time and grew pot out there on government land, and I really got into the Hawaiian way of life and just nature out there, the greenness and the livingness of the rain forest. It's just so pure out there where the hotel moguls don't have their greasy colonialist paws on it yet, with the chrome and glass and penned-in dolphins and chlorinated-swimming-pool bars and the hills paved over with Day-Glo golf courses and the electric patrol carts to ward off trespassers and the guys who have to comb the sand out with rakes every morning. We lived in an abandoned toolshed/bungalow thing that this botanist had originally built as a field station. The roaches bit, although you understand out there because they're hungry too. You kind of got to understand the Jainists with their temples with the plank floors over the insects and just that basically every creature has just as much right to do whatever as you do. So anyway we lived out there maybe a couple of years and slowed way down, no telephone, newspaper, or any of that shit--shut out all the noise. The problem was, the government was trying to wipe us off the map--not that we were on the map, but the Feds were always looking--and we had to move a lot of times, plus there were naturally poachers and we had to set traps, and so of course we had to worry all the time some hiker would get killed walking the wrong way. We had to keep a gun out there too, which was a pain in the ass morally, because I've always been a complete pacifist. Looking back, we definitely would've gotten killed if we were any better at farming than we were, but we didn't grow much surplus--the marketing scene was something we were just not that into. I would compare what we did more to the eighteenth-century utopia "Make your garden grow."

As it turned out Kekui's (the guy I was living with's) father died, we heard through his sister Roslind. So we fly into Honolulu for the funeral, a shock, let me tell you, coming into Disneyland, with the high-school kids in aloha-print bathing suits with those plumeria leis on their arms or decapitated carnations strung together--"lei greeters" for the package tours and the Japanese honeymooners in their white white tennis whites. And in front of all of them is Mrs. Eldridge standing with her car keys in her red muumuu and her hair piled up on her head with a red hibiscus at her ear--a big woman, not fat, big like an opera singer, big like photos of Princess Ruth when she sat at the Summer Palace on her throne.

We got to the funeral up in Makiki at the church there, I forget the name, and after the ceremony in the car she, meaning Mrs. Eldridge, turns to Kekui and me, who she hasn't said a word to all day, and she says, "KK, you're coming home."

"What?" he says.

"Roslind and her kids have the back room, Minnie and her kids are in front, Earl and Matthew have Minnie's room, Leilan and Mitchell are upstairs," she says.

"What?" he says.

"We cleaned out your room," she tells him.

"Excuse me?" I say.

"Keep quiet, girl," she says. We drive up to their house in Aina Hina with two plumeria trees in front, not a flower left--they picked them all off for the grandkids' May Day pageant. She had six of the eight kids living in the house and about five grandchildren. There were all these add-ons in back and a second story above the garage--Mr. Eldridge was a contractor. And there were something like seven cars in the driveway plus a boat and a tour van, just to give you an idea. We sit down inside, everyone depressed from the funeral, some of the babies crying. Mrs. Eldridge takes them on her knee, she looks around like she was ready to take everyone on her knee. For what? To rock us? To hit us? "KK," she says, "you've come back home to stay."

"Excuse me?" I say.

"Quiet, girl," she says.

"I have an application for you," she says. She brings out a bunch of forms. "West Oahu College," she says. "I brought up all my children to go to college. Okay?"

KK looks down totally crushed with this heavy guilt--he never went to visit his parents or his father before he died, and this was probably some oedipal thing with his father dying and him coming home to Mother--the minister at the funeral gave a whole speech about obedience and duty to the parents in times of sorrow.

"Everyone in this family is a worker," she says. "You filling this out?" She gives him the application forms.

"Yeah," he says.

"Goddammit!" I get up off the floor. "You dickless idiot! Don't you care about me at all? You're going to leave me in Molokai so you can live with your mother?"

"Get your mouth out of my house," Mrs. Eldridge declares, standing up in her full dimensions. "Hippie girl, just 'cause you washed up here on Oahu you don't need to come invading my family. Go back to where you started--California, England, Holland, or whatever nationality you are. And don't you dare walk around taking the Lord's name in vain blaspheming my husband's funeral. Get your pakalolo face away or Earl'll get his badge out and arrest you!"

* * *

So the upshot was Kekui and I broke up and I ended up getting a job at Paradise Jeweller and actually picked up some Cantonese there and got kind of close with the family--went to a lot of the family functions and stuff like that. They were working on evangelizing me and we had some really interesting conversations--they were Pentecostalists--and I went to church with them a couple of times out of my interest in religion. This is what I think you don't realize about me, Dr. Friedell, that this has been my lifelong interest--don't tell me I haven't thought about the concepts. So that's when I started at the university and took religion courses. And they were great experiences, let me make that clear--I never had a problem until you. I got an A in Hindu Myth, I got an A in Jesus and Liberation, and only your course threw me for a loop--I mean, can I be honest? Religious Thinkers has been totally frustrating in that you keep sidestepping the issues and you are totally obsessed with detail--I mean, were you raised a Pharisee?

So the point is I sat there in Moore Hall, I listened, I read these books you were assigning, but what you couldn

Dr. Friedell,

This is to apologize if I offended you in class a few weeks ago, though I realize you probably forgot the whole thing by now. I was the one who stood up and said "Fuck Augustine." What I meant was I didn't take the class to read him, I took it to learn about religion--God, prayer, ritual, the Madonna mother-goddess figure, forgiveness, miracles, sin, abortion, death, the big moral concepts. Because obviously I am not eighteen and I work, so school is not an academic exercise for me, and not just me, as I'm sure you'd realize if you looked around the room one of these days and saw there are thirty- and forty-year-olds and some a lot older than you are in the class--the point is, when you've been through marriage, kids, jobs, welfare, and the whole gamut and you come back to school you're ready for the real thing, and as far as I'm concerned Augustine's Conception of the Soul or whatever is not it. What is "it"? you're asking--well, that's what I came to find out, so you tell me. Obviously what you are paid for is to deal with the big religious issues and you are not dealing with them, which is what I was trying to point out when I made that remark in class, which I apologize for tone-wise but not for my feelings behind it.

My feelings still are that basically as a "mature student" I was supposed to feel grateful that the University of Hawaii let me in or gave me a second chance on life or whatever, like I am the lowly unwashed and I should come in the gates to be blessed by the big phallus. Or I am a housewife coming "back" to "school" driving my white Isuzu and eating my curds and whey. Look, I didn't come to salivate at your office door. You like to make distinctions, so you should make distinctions between you the employee and me the customer. You're the guy behind the counter.

Can I take a guess at what you're thinking?--"Another crazed woman in my class anti the educational system." But I'm not, I'm putting everything I've got on the line for religion.

Because the thing is that after I walked out on your class I sat down by the sausage trees near Moore Hall and I started watching the undergrads walking by in their Bermuda shorts going to lunch without a thought in their heads. I felt bad because for some reason I sort of believed in the universe part of university, that it was all about Life and Time and God, and Freedom, and when I got back in it was just so male and linear and there wasn't any magic in the religion classes, it was all a construct--the angels were symbols and the miracles were just things in nature. So I got up and took all my books to the bookstore and sold them back (for less than half what I paid for them) and I went home--a room in a termite palace. As I was saying before, I felt really bad because I think you might have the wrong idea about me--you probably don't know how into school I really was. I originally dropped out of Simmons in 1974 for a lot of reasons, my father died for one thing, but basically because I didn't see myself in school at that time in my life. The only thing I could really see myself doing was folk dancing--I was in the original core Israeli folk-dancing group at MIT, which you probably have never even heard of, but it's actually nationally famous--it's almost like the model for all the other clubs in the country. I spent those "college" years living in Brighton and dancing. When I say dancing I'm talking about a way of life--I knew over two hundred dances and I also did Balkan. We would get over to MIT and dance straight from 8:30 to 11 p.m., steaming into Walker Gym straight from the snow to sweat like you would not believe. We stripped down every night from coats, sweaters, and boots to tank tops, gauze skirts, bare feet, and cutoffs, and when we left we were so hot we carried our parkas under our arms. I actually knew a lot of the key people in the folk scene and performed in New York at some of the big festivals. So that was kind of my "schooling." I was a secretary--actually for two years I temped, we were all menial slaves in the folk club, with a few graduate students and programmers sprinkled in. At the time I was in a relationship with one of them, which is how I ended up going to Hawaii--he had an upgrade deal. After a week he freaked out and took off for Fiji, and I was stranded at a fleabag joint in Waikiki with about twenty-two dollars to my name and the room bill.

When he took off I sold my return ticket and got a job busing tables at Zippy's, then I worked in the kitchen doing prep, then I worked in the find-a-pearl oyster stand in the International Marketplace, then I sold gold electroplated cockroaches when they were in, then I sold paraphernalia and sex toys in back where Oriental Imports used to be, behind The Stop Light and the bikini store on King Street, then after that place folded I got a job in Crack Seed World, then I landed a job in luggage at Shirokya, worked at Longs Drugs checkout, and did inventory at The Good Earth. I was thinking about going back to Boston. Thinking a lot, Dr. Friedell--it was happening at an underground level. I realize you aren't interested in what kind of thinking a student who walks out of Augustine is experiencing, because you can't think about anything that hasn't been totally hashed out already by geniuses--that's the impression you give me anyway, all that stuff about us living on the last mushroom of the dunghill of Romanticism and standing on the shoulders of giants, and all you can do when you go back to school is learn how to use the library and document everything. Why do they make such a big deal about plagiarism if it's all been said already? Not that I think you're actually reading this, since it's written on onionskin in ball-point when you only accept typed stuff.

While I was working those different jobs I taught folk dancing at Kaimuki Y (once) and the temple (five x). I went to a Hebrew class at the temple because I was teaching all these dances to Israeli music and I didn't know Hebrew, but every time we would get past the alphabet some new guy or some kid would come into the class and we had to learn the alphabet again, so I never got beyond the letters. A total joke. Rabbi Siegel up at the temple used to go on these digressions, so obviously we never got anywhere, and finally after class I went up and said, "Rabbi, aren't we all just wasting time in here?"

He looks at me under the fluorescent lights in the Learning Center, which is all white linoleum and woodgrain tables and green plastic chairs, and nailed up on the walls all the Old World stuff, those ticky-tacky pictures of the bearded men. Rabbi Siegel faces me in his suit with his silver tie pin. "Sharon," he says, "I'm sorry you feel that way."

"I want to learn Hebrew," I said. "Isn't that what we're here for?"

"Sharon, I think you realize that in the end the words are the least important aspect of what I'm trying to teach. Come here," he says, pushing me into the sanctuary. He was one of those big-time formal rabbis who wore black robes at services and had like a whole set of hand signals for the organist--I think he was a frustrated conductor or actor. We go into the sanctuary and he flicks on the lights, floodlighting the temple ceiling, stained glass, et cetera. "Sharon," he says, "Judaism is more than a few simple phrases. It's a culture, one of music & art, poetry & light, it is the intimate & the sublime, exalted &"--I forget the exact words. "Think of the lyric music of the Psalms," he tells me. "While the Egyptians were building tombs we were singing of life and love, while the monuments of the ancients were crumbling to dust we were treading over the ruins in a tradition that arced back over the millennia and forward to the future. Our friends in class may never remember a word of Hebrew, but if they can sense something of the grandeur of our tradition the historic sweep of the epic blah blah blah chosen people."

I guess I sort of gave him a look, because this chosen-people crap was always one of my big problems with organized religion.

He heaves a big sigh, folds his arms over his belly. "I think you know how strongly I feel about that one," he says. "Each people is dear to God in its own way, and I often make the analogy to the different states of the Union." He was a great guy, Siegel, but when you asked him a question it was like throwing a bottle in the ocean and just watching it drift away over all his metaphors and comparisons plus the incidents it reminded him of. And as far as where I was coming from in the folk movement, he hadn't a clue because he was into "High" art, which goes back to what I was saying about the past. Siegel used to say "When I say the Bor'chu--"Bless ye the Lord'--I think how fitting a trumpet fanfare would be right there."

Meanwhile I was getting really alienated, not so much by him but by life in general, and by the kind of things I was doing, and I sort of disappeared for a while on Molokai with a guy I was having a relationship with at the time and grew pot out there on government land, and I really got into the Hawaiian way of life and just nature out there, the greenness and the livingness of the rain forest. It's just so pure out there where the hotel moguls don't have their greasy colonialist paws on it yet, with the chrome and glass and penned-in dolphins and chlorinated-swimming-pool bars and the hills paved over with Day-Glo golf courses and the electric patrol carts to ward off trespassers and the guys who have to comb the sand out with rakes every morning. We lived in an abandoned toolshed/bungalow thing that this botanist had originally built as a field station. The roaches bit, although you understand out there because they're hungry too. You kind of got to understand the Jainists with their temples with the plank floors over the insects and just that basically every creature has just as much right to do whatever as you do. So anyway we lived out there maybe a couple of years and slowed way down, no telephone, newspaper, or any of that shit--shut out all the noise. The problem was, the government was trying to wipe us off the map--not that we were on the map, but the Feds were always looking--and we had to move a lot of times, plus there were naturally poachers and we had to set traps, and so of course we had to worry all the time some hiker would get killed walking the wrong way. We had to keep a gun out there too, which was a pain in the ass morally, because I've always been a complete pacifist. Looking back, we definitely would've gotten killed if we were any better at farming than we were, but we didn't grow much surplus--the marketing scene was something we were just not that into. I would compare what we did more to the eighteenth-century utopia "Make your garden grow."

As it turned out Kekui's (the guy I was living with's) father died, we heard through his sister Roslind. So we fly into Honolulu for the funeral, a shock, let me tell you, coming into Disneyland, with the high-school kids in aloha-print bathing suits with those plumeria leis on their arms or decapitated carnations strung together--"lei greeters" for the package tours and the Japanese honeymooners in their white white tennis whites. And in front of all of them is Mrs. Eldridge standing with her car keys in her red muumuu and her hair piled up on her head with a red hibiscus at her ear--a big woman, not fat, big like an opera singer, big like photos of Princess Ruth when she sat at the Summer Palace on her throne.

We got to the funeral up in Makiki at the church there, I forget the name, and after the ceremony in the car she, meaning Mrs. Eldridge, turns to Kekui and me, who she hasn't said a word to all day, and she says, "KK, you're coming home."

"What?" he says.

"Roslind and her kids have the back room, Minnie and her kids are in front, Earl and Matthew have Minnie's room, Leilan and Mitchell are upstairs," she says.

"What?" he says.

"We cleaned out your room," she tells him.

"Excuse me?" I say.

"Keep quiet, girl," she says. We drive up to their house in Aina Hina with two plumeria trees in front, not a flower left--they picked them all off for the grandkids' May Day pageant. She had six of the eight kids living in the house and about five grandchildren. There were all these add-ons in back and a second story above the garage--Mr. Eldridge was a contractor. And there were something like seven cars in the driveway plus a boat and a tour van, just to give you an idea. We sit down inside, everyone depressed from the funeral, some of the babies crying. Mrs. Eldridge takes them on her knee, she looks around like she was ready to take everyone on her knee. For what? To rock us? To hit us? "KK," she says, "you've come back home to stay."

"Excuse me?" I say.

"Quiet, girl," she says.

"I have an application for you," she says. She brings out a bunch of forms. "West Oahu College," she says. "I brought up all my children to go to college. Okay?"

KK looks down totally crushed with this heavy guilt--he never went to visit his parents or his father before he died, and this was probably some oedipal thing with his father dying and him coming home to Mother--the minister at the funeral gave a whole speech about obedience and duty to the parents in times of sorrow.

"Everyone in this family is a worker," she says. "You filling this out?" She gives him the application forms.

"Yeah," he says.

"Goddammit!" I get up off the floor. "You dickless idiot! Don't you care about me at all? You're going to leave me in Molokai so you can live with your mother?"

"Get your mouth out of my house," Mrs. Eldridge declares, standing up in her full dimensions. "Hippie girl, just 'cause you washed up here on Oahu you don't need to come invading my family. Go back to where you started--California, England, Holland, or whatever nationality you are. And don't you dare walk around taking the Lord's name in vain blaspheming my husband's funeral. Get your pakalolo face away or Earl'll get his badge out and arrest you!"

* * *

So the upshot was Kekui and I broke up and I ended up getting a job at Paradise Jeweller and actually picked up some Cantonese there and got kind of close with the family--went to a lot of the family functions and stuff like that. They were working on evangelizing me and we had some really interesting conversations--they were Pentecostalists--and I went to church with them a couple of times out of my interest in religion. This is what I think you don't realize about me, Dr. Friedell, that this has been my lifelong interest--don't tell me I haven't thought about the concepts. So that's when I started at the university and took religion courses. And they were great experiences, let me make that clear--I never had a problem until you. I got an A in Hindu Myth, I got an A in Jesus and Liberation, and only your course threw me for a loop--I mean, can I be honest? Religious Thinkers has been totally frustrating in that you keep sidestepping the issues and you are totally obsessed with detail--I mean, were you raised a Pharisee?

So the point is I sat there in Moore Hall, I listened, I read these books you were assigning, but what you couldn

Recenzii

"Goodman is brilliant at capturing the clutter of both interior and exterior life."—Los Angeles Times

"Allegra Goodman is a remarkably gifted young writer, with a penchant for getting swiftly to the truth of things."—Chaim Potok

"Allegra Goodman is a remarkably gifted young writer, with a penchant for getting swiftly to the truth of things."—Chaim Potok

Descriere

In a collection of exquisite stories, Allegra Goodman fills rooms with laughter and voices, captures dinner parties, seaside picnics, academic grudges, shul politics, and the kind of hurts only families and lovers can know--a masterful work from one of the most powerful and eloquent voices on the American literary landscape.