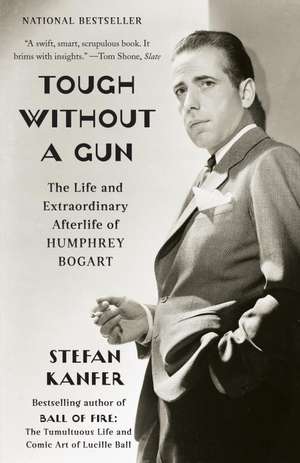

Tough Without a Gun: The Life and Extraordinary Afterlife of Humphrey Bogart

Autor Stefan Kanferen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 ian 2012

Preț: 114.60 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 172

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.93€ • 22.90$ • 18.15£

21.93€ • 22.90$ • 18.15£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 04-18 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307455819

ISBN-10: 0307455815

Pagini: 288

Ilustrații: 16 PP. B&W

Dimensiuni: 132 x 203 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Editura: VINTAGE BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0307455815

Pagini: 288

Ilustrații: 16 PP. B&W

Dimensiuni: 132 x 203 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Editura: VINTAGE BOOKS

Notă biografică

Stefan Kanfer’s books include Ball of Fire: The Tumultuous Life and Comic Art of Lucille Ball; Stardust Lost: The Triumph, Tragedy, and Mishugas of the Yiddish Theater in America; and Somebody: The Reckless Life and Remarkable Career of Marlon Brando. He was a writer and editor at Time for more than twenty years and was its first bylined film critic, a post he held between 1967 and 1972. He is also the primary interviewer in the Academy Award–nominated documentary The Line King and editor of an anthology of Groucho Marx’s comedy, The Essential Groucho. He is a Literary Lion of the New York Public Library and recipient of numerous writing awards. He lives in New York and on Cape Cod.

Extras

chapter 1

The End Depends on the Beginning

i

In the 150-year history of cinema, few performers have arrived with a more impressive résumé of monetary privilege and social distinction. Humphrey Bogart's father, Belmont DeForest Bogart, was a high-toned graduate of Phillips Andover prep school and Columbia University; his medical degree came from Yale. Belmont rarely failed to inform classmates and colleagues that the Bogarts of Holland were among the earliest settlers in New York, and that one of their ancestors was the first "European" child to be born in that state.

Actually, the Bogarts had been a line of burghers and truck farmers until Belmont's father, Adam, came along. He married late, became an innkeeper to support his wife and child, and compulsively tinkered in his off-hours. Lithography-etching on large, unwieldy stones-had become popular in the later nineteenth century; Adam seized the day, creating a process for transfering lithographs to portable sheets of tin. Printers wanted in on this new invention, and the sales made him a rich man. It was a classic case of an old family with new money, very much in the spirit of the nineteenth century. Adam relocated to Manhattan, taking comfort in the knowledge that many a New York City plutocrat had humble beginnings: Jacob Astor started out as a fur trapper; Peter Schermerhorn as a ship chandler; Frederick and William Rhinelander as bakers; Peter Lorillard as a tobacco merchant.

Adam maneuvered the family name into the Blue Book of New York City society and, after his wife died, concentrated all his energy and ambition on his only son. There would be no hayseed in this boy's hair; no scent of the carbolic acid used to clean hotel rooms would cling to his clothes as it had to his father's. Adam was sharply aware of Power of Personality, a book by the business writer Orison Swett Marden. "In this fiercely competitive age," warned the author, "when the law of the survival of the fittest acts with seemingly merciless rigor, no one can afford to be indifferent to the smallest detail of dress, or manner, or appearance, that will add to his chance of success." Adam's son was caparisoned in the right wardrobe, sent to the best private schools, given a generous allowance. Pushed and prodded to get on in this ruthless new world, Belmont aimed high. Early on, he made up his mind to major in science and biology, get admitted to Yale Medical School, and then forge his own reputation as a physician. By his early thirties Dr. Bogart had realized his goals, serving on the staffs of three prominent Manhattan hospitals: Bellevue, St. Luke's, and Sloan.

During that time, however, an accident wholly altered his life. He was riding in a horse-drawn ambulance when the animal got spooked in traffic, reared, and overturned the vehicle. Belmont's leg was broken, badly set, and then reset to correct the original errors. Morphine and other drugs were prescribed to lessen the misery. He leaned on them to get through the nights.

Still, he was tall, slim, and attractive; sporting a cane, he continued to make his professional rounds and attend parties, customarily introduced as one of the city's most eligible bachelors. It was at one of those preaccident fêtes that the thirty-year-old medical man had met the twenty-nine-year-old daughter of a Rochester, New York, stove salesman. Maud Humphrey was almost Belmont's height, not quite beautiful, but striking, with russet hair, a determined jaw, and a slender, shapely figure. She was also famous. At the age of sixteen the art prodigy had sold drawings to magazines. After studying in Paris and New York she caught on as an illustrator of calendars, children's books, and advertisements for Ivory soap and Metropolitan Life Insurance. Everywhere Belmont looked, he saw her pictures.

In their intelligent study, Maud Humphrey: Her Permanent Imprint on American Illustration, Karen Choppa and Paul Humphrey suggest that, skilled as she was, Maud owed much of her early success to industrial timing. Just as Enrico Caruso came along when single-sided wax recordings were being mass-produced, so Maud's meticulous watercolor technique turned out to be ideal for the brand-new methods of lithographic reproduction. Her renderings of moppets and misses were sentimental without being cloying, and expertly done; they made her the best-known illustrator of her time. When she and Belmont Bogart first met, he was drawing a yearly salary of twenty thousand dollars, an excellent sum in those days. Maud Humphrey was already earning more than twice as much.

A liaison began, interrupted by Maud's militant feminism: Belmont's nineteenth-century, male-centered view made the suffragist uncomfortable. They broke off. Two years later she heard about his accident and dropped by to express her sympathy. She paid another call, and another, and another. During one rendezvous the pair abruptly decided that personal politics be damned, they could not live without each other. A week later an item appeared in the Ontario County Times of June 15, 1898. It explained that in view of Dr. Bogart's indisposition,

Miss Humphrey thought she would rather nurse her husband through his trial than visit him duly chaperoned at stated intervals, so about the middle of the week the young couple announced casually that they were going to be married Saturday, and they were, with only a handful of cousins to give away the orphaned artist. The honeymoon will be spent in a hospital. Mrs. Bogart, nee Humphrey, is a connection of Admiral Dewey, and is also related to the Churchills and the Van Rensselaers.

The newlyweds bought a four-story town house at 245 West 103rd Street, between Riverside Drive and West End Avenue, then a toney address. Down the hill was Riverside Park, leading to the mile-wide Hudson River and the picturesque craggy Palisades; across the street was the Hotel Marseille, city home of folks like Sara Roosevelt, mother of the future president Franklin Delano Roosevelt. The Bogarts had four live-in help (two maids, a cook, and a laundress); their combined salaries added up to less than twenty dollars a week. In 1899, Maud gave birth to the Bogarts' first child and only son. He had something of his father's dark coloring, modified by his mother's delicate bone structure. The boy was christened with her maiden name, and there was great rejoicing. Before Humphrey was out of swaddling clothes Belmont made plans to enter him at Phillips Andover, predicting that someday young Bogart would become a doctor, like his old man. Over the next five years two daughters were added to the family. In keeping with Maud's progressive outlook, all three children were instructed to address her by her first name. None of them ever called her "Mother." She was not a great believer in hugs, either. A pat on the back or a soft clip on the shoulder was her way of showing affection. Belmont was undemonstrative as well, but this was in keeping with a man of his class and period. Thus he had enormous expectations of his handsome son; thus he assumed that Frances and Catherine would simply marry well and raise their own families. Maud demurred. They could have lives and jobs of their own; a new day was dawning for women. It was the beginning of many arguments about the family, and about life itself.

For more than a decade the three little Bogarts enjoyed an atmosphere of ostentatious comfort, surrounded by reproductions of classical statues, heavy tapestries, and overstuffed horsehair couches and chairs. They played with the latest toys, were luxuriously togged, and ate the best food money could buy. When Maud and Belmont dined out, it was at stylish restaurants like Delmonico's and the Lafayette, but those occasions were rare; they were around the house much of the time. The doctor received patients in a mahogany-lined office on the first floor, and the artist did her work in a studio at the top of the house. On many occasions she sketched and painted until after midnight, when the only sound was the cooing of pigeons on the roof. Belmont raised them in his spare time; it was one of his many hobbies. His favorite avocation was sailing, something he had done as a youth. To that end, the Bogarts acquired an estate on the exclusive shore of Canandaigua Lake, one of the long, wide Finger Lakes in upstate New York. Willow Brook's fifty-five acres contained a working farm, an icehouse, and broad lawns leading down to the dock where Belmont kept a yacht he called the Comrade.

So far, so Edwardian. Yet there were cracks in this grand façade, imperceptible to most outsiders but sadly apparent to Humphrey, Frances, and Catherine. For Maud and Belmont were running out of mutual affection. It was not a question of lovers or mistresses. They had gradually, and then not so gradually, grown apart, vanishing into their professional obligations and political beliefs, into alcohol, and, in Belmont's case, into morphine addiction. They fought much of the time, usually behind closed doors. But in hot weather secrets could not be kept so easily. Maud suffered from migraine headaches, and through the open windows her throaty voice could be overheard by neighbors, bawling out the children for some trivial misbehavior. Her outbursts were often followed by Belmont's own tantrums. Those could lead to harsh corporal punishment; like his father before him, Belmont was a believer in the razor strop as an instrument of moral instruction. At Willow Brook the children's lives veered between the terror of evening quarrels and the delights of lyrical summer afternoons.

For Humphrey, some of the pleasure came from his newfound role as leader of the Seneca Point Gang. This was a self-styled group of adolescent boys who addressed him as "Hump," a nickname he found congenial. They skinny-dipped in local streams, built their own clubhouse of spare planks, played war with lead soldiers, and put on amateurish stage plays at the lakefront beach. There was nothing remarkable about these productions except for the costumes. They were the real thing, Broadway discards donated by William Aloysius Brady, a patient of Dr. Bogart's.

Despite his Irish-sounding name, Bill Brady was a Jewish theatrical producer. At a time when New York society referred to Jews by such code references as NOKD (Not Our Kind, Darling) and restrictive covenants barred "Hebrews" from certain city neighborhoods, the Bogarts displayed few of the standard social biases. Maud was uncomfortable with Jews, but she considered herself a freethinker and a realist. One had to get along with all sorts of people these days. Belmont liked the idea of befriending a man who had managed two undisputed heavyweight champions, James Corbett and James Jeffries, bankrolled touring companies, married the glamorous actress Grace George, and owned the Playhouse Theater on 48th Street. Brady's son, Bill Jr., was an occasional houseguest and honorary gang member; more often he and Humphrey formed their own mini-gang back in the city, where they checked out Sarah Bernhardt and W. C. Fields at the Palace, broke up at the antics of Chaplin and Keaton, and gazed approvingly at the manly images of John Barrymore and Francis X. Bushman in nickelodeons. Bill Sr. had little use for movies-he told the boys they were a passing fad, full of exaggerated gestures by overemoting hambones. He was fond of quoting the director Marshall Neilan: "The sooner the stage people who have come into pictures get out, the better for the pictures."

The End Depends on the Beginning

i

In the 150-year history of cinema, few performers have arrived with a more impressive résumé of monetary privilege and social distinction. Humphrey Bogart's father, Belmont DeForest Bogart, was a high-toned graduate of Phillips Andover prep school and Columbia University; his medical degree came from Yale. Belmont rarely failed to inform classmates and colleagues that the Bogarts of Holland were among the earliest settlers in New York, and that one of their ancestors was the first "European" child to be born in that state.

Actually, the Bogarts had been a line of burghers and truck farmers until Belmont's father, Adam, came along. He married late, became an innkeeper to support his wife and child, and compulsively tinkered in his off-hours. Lithography-etching on large, unwieldy stones-had become popular in the later nineteenth century; Adam seized the day, creating a process for transfering lithographs to portable sheets of tin. Printers wanted in on this new invention, and the sales made him a rich man. It was a classic case of an old family with new money, very much in the spirit of the nineteenth century. Adam relocated to Manhattan, taking comfort in the knowledge that many a New York City plutocrat had humble beginnings: Jacob Astor started out as a fur trapper; Peter Schermerhorn as a ship chandler; Frederick and William Rhinelander as bakers; Peter Lorillard as a tobacco merchant.

Adam maneuvered the family name into the Blue Book of New York City society and, after his wife died, concentrated all his energy and ambition on his only son. There would be no hayseed in this boy's hair; no scent of the carbolic acid used to clean hotel rooms would cling to his clothes as it had to his father's. Adam was sharply aware of Power of Personality, a book by the business writer Orison Swett Marden. "In this fiercely competitive age," warned the author, "when the law of the survival of the fittest acts with seemingly merciless rigor, no one can afford to be indifferent to the smallest detail of dress, or manner, or appearance, that will add to his chance of success." Adam's son was caparisoned in the right wardrobe, sent to the best private schools, given a generous allowance. Pushed and prodded to get on in this ruthless new world, Belmont aimed high. Early on, he made up his mind to major in science and biology, get admitted to Yale Medical School, and then forge his own reputation as a physician. By his early thirties Dr. Bogart had realized his goals, serving on the staffs of three prominent Manhattan hospitals: Bellevue, St. Luke's, and Sloan.

During that time, however, an accident wholly altered his life. He was riding in a horse-drawn ambulance when the animal got spooked in traffic, reared, and overturned the vehicle. Belmont's leg was broken, badly set, and then reset to correct the original errors. Morphine and other drugs were prescribed to lessen the misery. He leaned on them to get through the nights.

Still, he was tall, slim, and attractive; sporting a cane, he continued to make his professional rounds and attend parties, customarily introduced as one of the city's most eligible bachelors. It was at one of those preaccident fêtes that the thirty-year-old medical man had met the twenty-nine-year-old daughter of a Rochester, New York, stove salesman. Maud Humphrey was almost Belmont's height, not quite beautiful, but striking, with russet hair, a determined jaw, and a slender, shapely figure. She was also famous. At the age of sixteen the art prodigy had sold drawings to magazines. After studying in Paris and New York she caught on as an illustrator of calendars, children's books, and advertisements for Ivory soap and Metropolitan Life Insurance. Everywhere Belmont looked, he saw her pictures.

In their intelligent study, Maud Humphrey: Her Permanent Imprint on American Illustration, Karen Choppa and Paul Humphrey suggest that, skilled as she was, Maud owed much of her early success to industrial timing. Just as Enrico Caruso came along when single-sided wax recordings were being mass-produced, so Maud's meticulous watercolor technique turned out to be ideal for the brand-new methods of lithographic reproduction. Her renderings of moppets and misses were sentimental without being cloying, and expertly done; they made her the best-known illustrator of her time. When she and Belmont Bogart first met, he was drawing a yearly salary of twenty thousand dollars, an excellent sum in those days. Maud Humphrey was already earning more than twice as much.

A liaison began, interrupted by Maud's militant feminism: Belmont's nineteenth-century, male-centered view made the suffragist uncomfortable. They broke off. Two years later she heard about his accident and dropped by to express her sympathy. She paid another call, and another, and another. During one rendezvous the pair abruptly decided that personal politics be damned, they could not live without each other. A week later an item appeared in the Ontario County Times of June 15, 1898. It explained that in view of Dr. Bogart's indisposition,

Miss Humphrey thought she would rather nurse her husband through his trial than visit him duly chaperoned at stated intervals, so about the middle of the week the young couple announced casually that they were going to be married Saturday, and they were, with only a handful of cousins to give away the orphaned artist. The honeymoon will be spent in a hospital. Mrs. Bogart, nee Humphrey, is a connection of Admiral Dewey, and is also related to the Churchills and the Van Rensselaers.

The newlyweds bought a four-story town house at 245 West 103rd Street, between Riverside Drive and West End Avenue, then a toney address. Down the hill was Riverside Park, leading to the mile-wide Hudson River and the picturesque craggy Palisades; across the street was the Hotel Marseille, city home of folks like Sara Roosevelt, mother of the future president Franklin Delano Roosevelt. The Bogarts had four live-in help (two maids, a cook, and a laundress); their combined salaries added up to less than twenty dollars a week. In 1899, Maud gave birth to the Bogarts' first child and only son. He had something of his father's dark coloring, modified by his mother's delicate bone structure. The boy was christened with her maiden name, and there was great rejoicing. Before Humphrey was out of swaddling clothes Belmont made plans to enter him at Phillips Andover, predicting that someday young Bogart would become a doctor, like his old man. Over the next five years two daughters were added to the family. In keeping with Maud's progressive outlook, all three children were instructed to address her by her first name. None of them ever called her "Mother." She was not a great believer in hugs, either. A pat on the back or a soft clip on the shoulder was her way of showing affection. Belmont was undemonstrative as well, but this was in keeping with a man of his class and period. Thus he had enormous expectations of his handsome son; thus he assumed that Frances and Catherine would simply marry well and raise their own families. Maud demurred. They could have lives and jobs of their own; a new day was dawning for women. It was the beginning of many arguments about the family, and about life itself.

For more than a decade the three little Bogarts enjoyed an atmosphere of ostentatious comfort, surrounded by reproductions of classical statues, heavy tapestries, and overstuffed horsehair couches and chairs. They played with the latest toys, were luxuriously togged, and ate the best food money could buy. When Maud and Belmont dined out, it was at stylish restaurants like Delmonico's and the Lafayette, but those occasions were rare; they were around the house much of the time. The doctor received patients in a mahogany-lined office on the first floor, and the artist did her work in a studio at the top of the house. On many occasions she sketched and painted until after midnight, when the only sound was the cooing of pigeons on the roof. Belmont raised them in his spare time; it was one of his many hobbies. His favorite avocation was sailing, something he had done as a youth. To that end, the Bogarts acquired an estate on the exclusive shore of Canandaigua Lake, one of the long, wide Finger Lakes in upstate New York. Willow Brook's fifty-five acres contained a working farm, an icehouse, and broad lawns leading down to the dock where Belmont kept a yacht he called the Comrade.

So far, so Edwardian. Yet there were cracks in this grand façade, imperceptible to most outsiders but sadly apparent to Humphrey, Frances, and Catherine. For Maud and Belmont were running out of mutual affection. It was not a question of lovers or mistresses. They had gradually, and then not so gradually, grown apart, vanishing into their professional obligations and political beliefs, into alcohol, and, in Belmont's case, into morphine addiction. They fought much of the time, usually behind closed doors. But in hot weather secrets could not be kept so easily. Maud suffered from migraine headaches, and through the open windows her throaty voice could be overheard by neighbors, bawling out the children for some trivial misbehavior. Her outbursts were often followed by Belmont's own tantrums. Those could lead to harsh corporal punishment; like his father before him, Belmont was a believer in the razor strop as an instrument of moral instruction. At Willow Brook the children's lives veered between the terror of evening quarrels and the delights of lyrical summer afternoons.

For Humphrey, some of the pleasure came from his newfound role as leader of the Seneca Point Gang. This was a self-styled group of adolescent boys who addressed him as "Hump," a nickname he found congenial. They skinny-dipped in local streams, built their own clubhouse of spare planks, played war with lead soldiers, and put on amateurish stage plays at the lakefront beach. There was nothing remarkable about these productions except for the costumes. They were the real thing, Broadway discards donated by William Aloysius Brady, a patient of Dr. Bogart's.

Despite his Irish-sounding name, Bill Brady was a Jewish theatrical producer. At a time when New York society referred to Jews by such code references as NOKD (Not Our Kind, Darling) and restrictive covenants barred "Hebrews" from certain city neighborhoods, the Bogarts displayed few of the standard social biases. Maud was uncomfortable with Jews, but she considered herself a freethinker and a realist. One had to get along with all sorts of people these days. Belmont liked the idea of befriending a man who had managed two undisputed heavyweight champions, James Corbett and James Jeffries, bankrolled touring companies, married the glamorous actress Grace George, and owned the Playhouse Theater on 48th Street. Brady's son, Bill Jr., was an occasional houseguest and honorary gang member; more often he and Humphrey formed their own mini-gang back in the city, where they checked out Sarah Bernhardt and W. C. Fields at the Palace, broke up at the antics of Chaplin and Keaton, and gazed approvingly at the manly images of John Barrymore and Francis X. Bushman in nickelodeons. Bill Sr. had little use for movies-he told the boys they were a passing fad, full of exaggerated gestures by overemoting hambones. He was fond of quoting the director Marshall Neilan: "The sooner the stage people who have come into pictures get out, the better for the pictures."

Recenzii

"A swift, smart, scrupulous book. It brims with insights." —Tom Shone, Slate

"Terrific. . . . Kanfer is particularly good in sketching [Bogart's] lasting influence." —Los Angeles Times

"Evocative. . . . Gives the reader a palpable sense of the sadly truncated arc of [Bogart's] life." —Michiko Kakutani, The New York Times

"Insightful. . . . The value of this book lies in Kanfer's insights into and analysis of the way that Bogart worked " —Chicago Sun-Times

"There may be no better analysis of Bogart’s mysterious and enduring appeal." —The Daily Beast

“Gracefully written. . . . [Kanfer] approaches the complicated and difficult man Katharine Hepburn called ‘one of the biggest guys I ever met’ with a fair, discerning eye. . . . Both sensitive and agile. . . . An insightful, compassionate portrait of a man who cared about his craft and, close friends said, camouflaged a kind and generous heart with a sardonic wit and snarl.” —Dallas Morning News

“Excellent. . . . A moving, psychologically intimate portrait of an icon that leaves some of the mystique intact.” —A.V. Club

“A readable and entertaining biography that reflects the author’s delight in his subject and the world in which Bogart thrived.” —Denver Post

“If you, like most of us, think of Bogart in Casablanca, The African Queen, and perhaps The Maltese Falcon, and you’ve always wondered what was behind the cool guy in the trench coat and the fedora, this book will tell you—in spades.” —Providence Journal

“Numerous…apt descriptions of Bogart’s film persona flow through Kanfer’s [book].” —Courier-Journal

“Kanfer does a thorough job of taking us on a journey through the making of Bogart’s other films. . . . Kanfer is at his best when framing Bogie’s career against the social and cultural mood of each era, and exploring Bogie’s flourishing cult status since his death in 1957.” —Newsday

“[Kanfer’s] skill with words is as smooth as the Scotch Bogart loved. . . . With this biography, just sit back and savour. Kanfer takes you enjoyably through stories.” —Vancouver Sun

“It's the afterlife that matters, and the best part of Mr. Kanfer's account is his analysis of Bogart's role as what cultural historians call a "modal personality" of his time—and what a long time it has been." —The Wall Street Journal

"Terrific. . . . Kanfer is particularly good in sketching [Bogart's] lasting influence." —Los Angeles Times

"Evocative. . . . Gives the reader a palpable sense of the sadly truncated arc of [Bogart's] life." —Michiko Kakutani, The New York Times

"Insightful. . . . The value of this book lies in Kanfer's insights into and analysis of the way that Bogart worked " —Chicago Sun-Times

"There may be no better analysis of Bogart’s mysterious and enduring appeal." —The Daily Beast

“Gracefully written. . . . [Kanfer] approaches the complicated and difficult man Katharine Hepburn called ‘one of the biggest guys I ever met’ with a fair, discerning eye. . . . Both sensitive and agile. . . . An insightful, compassionate portrait of a man who cared about his craft and, close friends said, camouflaged a kind and generous heart with a sardonic wit and snarl.” —Dallas Morning News

“Excellent. . . . A moving, psychologically intimate portrait of an icon that leaves some of the mystique intact.” —A.V. Club

“A readable and entertaining biography that reflects the author’s delight in his subject and the world in which Bogart thrived.” —Denver Post

“If you, like most of us, think of Bogart in Casablanca, The African Queen, and perhaps The Maltese Falcon, and you’ve always wondered what was behind the cool guy in the trench coat and the fedora, this book will tell you—in spades.” —Providence Journal

“Numerous…apt descriptions of Bogart’s film persona flow through Kanfer’s [book].” —Courier-Journal

“Kanfer does a thorough job of taking us on a journey through the making of Bogart’s other films. . . . Kanfer is at his best when framing Bogie’s career against the social and cultural mood of each era, and exploring Bogie’s flourishing cult status since his death in 1957.” —Newsday

“[Kanfer’s] skill with words is as smooth as the Scotch Bogart loved. . . . With this biography, just sit back and savour. Kanfer takes you enjoyably through stories.” —Vancouver Sun

“It's the afterlife that matters, and the best part of Mr. Kanfer's account is his analysis of Bogart's role as what cultural historians call a "modal personality" of his time—and what a long time it has been." —The Wall Street Journal

Descriere

Kanfer delivers the definitive biography of one of the great movie icons of the 20th century, and a wide-reaching appraisal of the actor's singular legacy. Through it all, Kanfer paints a background of the social and cultural context in which Bogart became, for all time, the one and only Bogie.