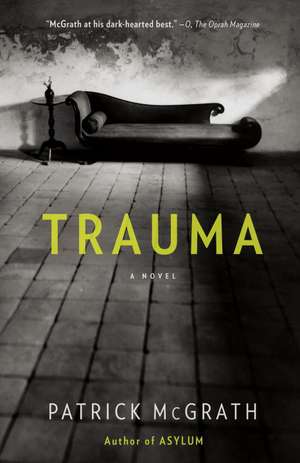

Trauma

Autor Patrick McGrathen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mar 2009

Preț: 82.70 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 124

Preț estimativ în valută:

15.83€ • 16.35$ • 13.17£

15.83€ • 16.35$ • 13.17£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400075492

ISBN-10: 1400075491

Pagini: 226

Dimensiuni: 132 x 204 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 1400075491

Pagini: 226

Dimensiuni: 132 x 204 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Notă biografică

Patrick McGrath is the author of six previous novels, including Asylum and Spider, and two collections of stories. He lives in New York.

Extras

My mother’s first depressive illness occurred when I was seven years old, and I felt it was my fault. I felt I should have prevented it. This was about a year before my father left us. His name was Fred Weir. In those days he could be generous, amusing, an expansive man—my brother, Walt, plays the role at times—but there were signs, perceptible to me if not to others, when an explosion was imminent. Then the sudden loss of temper, the storming from the room, the slamming door at the end of the hall and the appalled silence afterward. But I could deflect all this. I would play the fool, or be the baby, distract him from the mounting wave of boredom and frustration he must have felt at being trapped within the suffocating domestic atmosphere my mother liked to foster. Later, when she began writing books, she fostered no atmosphere at all other than genteel squalor and heavy drinking and gloom. But by then my father was long gone.

In those days we lived in shabby discomfort in a large apartment on West Eighty-seventh Street, where my brother lives with his family today. I never contested Walt’s right to have it after Mom died, and have come to terms with the fact that to me she left nothing. Indeed, it amuses me that she would throw this one last insult in my face from beyond the grave. It was more appropriate that Walt should have the apartment, given the size of his family, and me living alone, although Walt didn’t actually need the apartment. Walt was a wealthy man—Walter Weir, the painter? But I don’t resent this, although having said that, or rather, had I heard one of my patients say it, I would at once detect the anger behind the words. With consummate skill I would then extricate the truth, bring it up to the surface where we both could face it square: You hated your mother! You hate her still!

I am, as will be apparent by now, a psychiatrist. I do professionally that which you do naturally for those you care for, those whose welfare has been entrusted to you. My office was for many years on Park Avenue, which is less impressive than it sounds. The rent was low, and so were my fees. I worked mostly with victims of trauma, who of all the mentally disturbed people in the city of New York feel it most acutely, that they are owed for what they’ve suffered. It makes them slow to pay their bills. I chose this line of work because of my mother, and I am not alone in this. It is the mothers who propel most of us into psychiatry, usually because we have failed them.

Often a patient will be referred to me, and after the preliminaries have been completed and he, or more usually she, is settled comfortably, this will be her question: Where would you like me to begin?

“Just tell me what you’ve been thinking about.”

“Nothing.”

“What were you thinking about on your way to this appointment?”

And so it begins. I listen. Mine is a profession that might on the surface appear to suit the passive personality. But don’t be too quick to assume that we are uninterested in power. I sit there pondering while you tell me your thoughts, and with my grunts and sighs, my occasional interruptions, I guide you toward what I believe to be the true core and substance of your problem. It is not a scientific endeavor. No, I feel my way into your experience with an intuition based on little more than a few years of practice, and reading, and focused introspection; in other words, there is much of art in what I do.

My mother did eventually recover, but there is a strong correlation between depression and anger and at some level she stayed angry. It was largely directed at my father, of course. I have a clear memory of the day I first became aware of my parents’ dynamic of abandonment and rage. Fred had taken Walter and me to lunch, a thing he did occasionally when he was in town and remembered that he had two sons living on West Eighty-seventh Street. For me these were stressful events, starting with the cab ride to an East Side steakhouse, though in fact any time spent with my father was stressful. One summer he took us on a road trip upstate to a hotel in the Catskills, a journey of pure unmitigated hell, the endless hours sitting beside Walter in the back of the Buick as we drove through the endless mountains, and the atmosphere never less than explosive—

Fred Weir was still handsome then, his dark hair swept back from a sharp peak in a high-templed forehead, a tall, athletic fellow with a charming grin. He wasn’t a successful man but he gave the impression of being one, and when he took us out to lunch I marveled at the peremptory tone with which he addressed the waiters, brisk unsmiling men in starched white aprons who, in that adult room of wood paneling and cigar smoke, thoroughly intimidated the lanky, nervous adolescent I then was. My anxiety was not eased by the presence of steak knives with heavy wooden handles and sharp serrated blades, and a sort of diabolical trolley that was wheeled, steaming, to the table by a stout man with a pencil mustache who with the flourish of a gleaming knife indicated the meat and demanded to know where I wanted it carved.

When Fred grew bored with us and showed signs of calling for the check, Walt would ask him for investment advice, claiming to have considerable funds stashed away. Walt was always more curious about our father than I was. As a boy he was intrigued as to what went on in our parents’ bedroom, when they shared a bedroom, that is. He wanted to get in there and find out what they did.

Mom was distressed when we returned from these outings, having in our absence awoken to the possibility that Fred might exert a stronger influence over her boys than she did and that we too would then be lost to her. It fell to me to assure her of our love and loyalty. Then she lavished her affection on me for a while, until she grew distracted and drifted off down the hall to her study. Hearing the door close and the tap-tap-tap of the typewriter, I knew she would not come out before it was time for a cocktail. I was comforted by the sound of the typewriter. If she was typing then she wasn’t crying, although later she was able to do both at once.

But I remember one day when we returned to the apartment and she wasn’t waiting in the hallway as we came up the stairs. This was unusual. We let ourselves in and at once heard her crying in her bedroom. It was pitiful. Walter said he was going out again, I could do what I wanted. I see myself with great clarity at that moment. The choice was simple. I could walk out of the apartment with him and spend an hour or two in Central Park, or I could go and knock on my mother’s bedroom door and ask her what was wrong. I remember sitting down on the chair in the hallway, beside the low desk with the telephone on it, where she always left her keys on the tray and fixed her hair in the mirror on the wall above it.

“I’m not waiting,” Walt said from the front door.

A sudden fresh gust of misery from the bedroom.

“I think I’ll stay.”

“Suit yourself,” he said, and the front door closed behind him.

For another minute I sat on the chair in the hallway, then stood up and walked slowly toward her room. This is how psychiatrists are made.

Much of my later childhood and adolescence followed this pattern. I did not make friends easily, and I was more content by far with a book than with the company of my contemporaries. Walter by contrast was a gregarious boy and often brought his friends back to the apartment. This was a source of pleasure to my mother, although if she was depressed she would withdraw to her bedroom. At times like this it was a cause of concern to me that Walter’s friends made so much noise. I remember I stood in the doorway of the living room once and asked them to be quiet, as Mom was resting. They were dancing to Bill Haley. Walter would have been about seventeen; I was three years younger. I remember he turned the record player off and they all stared at me, six or seven of them, older kids I’d seen in the corridors of the high school we attended on the Upper West Side.

“What did you say?” said Walter.

If it hadn’t been for the fact that Mom was trying to sleep I would have fled.

“I said, I think you should turn it down.”

They all stared at me in silence. It was a form of mockery. “What did you say?” said Walter again.

“Turn it down! She’s trying to get some sleep!”

He looked at the others and solemnly repeated my words. They started laughing. They slapped their thighs, they yelped like hyenas; they lifted their heads and howled, all to humiliate me. Then Mom’s bedroom door opened down the hall. She shuffled toward the living room, yawning. She was in her robe, barefoot, and she hadn’t brushed her hair. It was the middle of the afternoon and I felt embarrassed for her in front of Walter’s friends, who had fallen silent. She stood in the doorway and asked what was going on, and Walter told her. She was still half asleep. She turned to me.

“Don’t be silly, Charlie, I was only reading. You people have fun, I don’t care.”

She went back to her room with a wave of her hand and I left the apartment feeling angry and ashamed.

When I returned to New York after my residency at Johns Hopkins, I didn’t move back to Eighty-seventh Street. Mom told me she didn’t want me in the apartment. She said she needed silence in order to write. I understood what she was telling me. It was not a rejection, though it was framed in those terms, because she also gave me a new set of keys. Don’t abandon me, she was saying. She was stabilized on antidepressants but there were still times when she would suddenly, precipitately go down, and then it was me she needed.

From the Hardcover edition.

In those days we lived in shabby discomfort in a large apartment on West Eighty-seventh Street, where my brother lives with his family today. I never contested Walt’s right to have it after Mom died, and have come to terms with the fact that to me she left nothing. Indeed, it amuses me that she would throw this one last insult in my face from beyond the grave. It was more appropriate that Walt should have the apartment, given the size of his family, and me living alone, although Walt didn’t actually need the apartment. Walt was a wealthy man—Walter Weir, the painter? But I don’t resent this, although having said that, or rather, had I heard one of my patients say it, I would at once detect the anger behind the words. With consummate skill I would then extricate the truth, bring it up to the surface where we both could face it square: You hated your mother! You hate her still!

I am, as will be apparent by now, a psychiatrist. I do professionally that which you do naturally for those you care for, those whose welfare has been entrusted to you. My office was for many years on Park Avenue, which is less impressive than it sounds. The rent was low, and so were my fees. I worked mostly with victims of trauma, who of all the mentally disturbed people in the city of New York feel it most acutely, that they are owed for what they’ve suffered. It makes them slow to pay their bills. I chose this line of work because of my mother, and I am not alone in this. It is the mothers who propel most of us into psychiatry, usually because we have failed them.

Often a patient will be referred to me, and after the preliminaries have been completed and he, or more usually she, is settled comfortably, this will be her question: Where would you like me to begin?

“Just tell me what you’ve been thinking about.”

“Nothing.”

“What were you thinking about on your way to this appointment?”

And so it begins. I listen. Mine is a profession that might on the surface appear to suit the passive personality. But don’t be too quick to assume that we are uninterested in power. I sit there pondering while you tell me your thoughts, and with my grunts and sighs, my occasional interruptions, I guide you toward what I believe to be the true core and substance of your problem. It is not a scientific endeavor. No, I feel my way into your experience with an intuition based on little more than a few years of practice, and reading, and focused introspection; in other words, there is much of art in what I do.

My mother did eventually recover, but there is a strong correlation between depression and anger and at some level she stayed angry. It was largely directed at my father, of course. I have a clear memory of the day I first became aware of my parents’ dynamic of abandonment and rage. Fred had taken Walter and me to lunch, a thing he did occasionally when he was in town and remembered that he had two sons living on West Eighty-seventh Street. For me these were stressful events, starting with the cab ride to an East Side steakhouse, though in fact any time spent with my father was stressful. One summer he took us on a road trip upstate to a hotel in the Catskills, a journey of pure unmitigated hell, the endless hours sitting beside Walter in the back of the Buick as we drove through the endless mountains, and the atmosphere never less than explosive—

Fred Weir was still handsome then, his dark hair swept back from a sharp peak in a high-templed forehead, a tall, athletic fellow with a charming grin. He wasn’t a successful man but he gave the impression of being one, and when he took us out to lunch I marveled at the peremptory tone with which he addressed the waiters, brisk unsmiling men in starched white aprons who, in that adult room of wood paneling and cigar smoke, thoroughly intimidated the lanky, nervous adolescent I then was. My anxiety was not eased by the presence of steak knives with heavy wooden handles and sharp serrated blades, and a sort of diabolical trolley that was wheeled, steaming, to the table by a stout man with a pencil mustache who with the flourish of a gleaming knife indicated the meat and demanded to know where I wanted it carved.

When Fred grew bored with us and showed signs of calling for the check, Walt would ask him for investment advice, claiming to have considerable funds stashed away. Walt was always more curious about our father than I was. As a boy he was intrigued as to what went on in our parents’ bedroom, when they shared a bedroom, that is. He wanted to get in there and find out what they did.

Mom was distressed when we returned from these outings, having in our absence awoken to the possibility that Fred might exert a stronger influence over her boys than she did and that we too would then be lost to her. It fell to me to assure her of our love and loyalty. Then she lavished her affection on me for a while, until she grew distracted and drifted off down the hall to her study. Hearing the door close and the tap-tap-tap of the typewriter, I knew she would not come out before it was time for a cocktail. I was comforted by the sound of the typewriter. If she was typing then she wasn’t crying, although later she was able to do both at once.

But I remember one day when we returned to the apartment and she wasn’t waiting in the hallway as we came up the stairs. This was unusual. We let ourselves in and at once heard her crying in her bedroom. It was pitiful. Walter said he was going out again, I could do what I wanted. I see myself with great clarity at that moment. The choice was simple. I could walk out of the apartment with him and spend an hour or two in Central Park, or I could go and knock on my mother’s bedroom door and ask her what was wrong. I remember sitting down on the chair in the hallway, beside the low desk with the telephone on it, where she always left her keys on the tray and fixed her hair in the mirror on the wall above it.

“I’m not waiting,” Walt said from the front door.

A sudden fresh gust of misery from the bedroom.

“I think I’ll stay.”

“Suit yourself,” he said, and the front door closed behind him.

For another minute I sat on the chair in the hallway, then stood up and walked slowly toward her room. This is how psychiatrists are made.

Much of my later childhood and adolescence followed this pattern. I did not make friends easily, and I was more content by far with a book than with the company of my contemporaries. Walter by contrast was a gregarious boy and often brought his friends back to the apartment. This was a source of pleasure to my mother, although if she was depressed she would withdraw to her bedroom. At times like this it was a cause of concern to me that Walter’s friends made so much noise. I remember I stood in the doorway of the living room once and asked them to be quiet, as Mom was resting. They were dancing to Bill Haley. Walter would have been about seventeen; I was three years younger. I remember he turned the record player off and they all stared at me, six or seven of them, older kids I’d seen in the corridors of the high school we attended on the Upper West Side.

“What did you say?” said Walter.

If it hadn’t been for the fact that Mom was trying to sleep I would have fled.

“I said, I think you should turn it down.”

They all stared at me in silence. It was a form of mockery. “What did you say?” said Walter again.

“Turn it down! She’s trying to get some sleep!”

He looked at the others and solemnly repeated my words. They started laughing. They slapped their thighs, they yelped like hyenas; they lifted their heads and howled, all to humiliate me. Then Mom’s bedroom door opened down the hall. She shuffled toward the living room, yawning. She was in her robe, barefoot, and she hadn’t brushed her hair. It was the middle of the afternoon and I felt embarrassed for her in front of Walter’s friends, who had fallen silent. She stood in the doorway and asked what was going on, and Walter told her. She was still half asleep. She turned to me.

“Don’t be silly, Charlie, I was only reading. You people have fun, I don’t care.”

She went back to her room with a wave of her hand and I left the apartment feeling angry and ashamed.

When I returned to New York after my residency at Johns Hopkins, I didn’t move back to Eighty-seventh Street. Mom told me she didn’t want me in the apartment. She said she needed silence in order to write. I understood what she was telling me. It was not a rejection, though it was framed in those terms, because she also gave me a new set of keys. Don’t abandon me, she was saying. She was stabilized on antidepressants but there were still times when she would suddenly, precipitately go down, and then it was me she needed.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“McGrath at his dark-hearted best.” —O, The Oprah Magazine“Beautifully crafted and paced, Trauma [is] either a superb psychological thriller or a masterly evocation of modern alienation and despair. . . . A terrific literary entertainment, one that will keep you on edge.” —The Washington Post “Full of sensitive, well-observed touches [and] elegant when it needs to be. . . . McGrath makes us see that our own minds are the most haunted of houses.” —Los Angeles Times“Ambitious. . . . McGrath uses his potent storytelling powers to draw us into [his narrator's] fevered brain and convey his emotional distress.” —The New York Times"The inversion of roles, the blurring of the boundaries between the rational and the irrational, the violence, the twisted sexual passions, the slipperiness of memory: these are familiar themes in McGrath's fiction. Here they are recombined in powerful and imaginative ways. Trauma is a gripping psychological thriller. McGrath's prose is taut and lean; his way with characters is deft; and his explorations of the dark side of human nature are disturbing. And at the novel's centre, the descent of its narrator from a false sense of superiority into a pit of madness and despair is handled with great skill." —Andrew Scull, The Times Literary Supplement“Tortuous, often gripping…The novel is aptly titled, since trauma can be said to be the origin and the end of its insidiously uncoiling developments.” —Sven Birkerts, The New York Times Book Review“A haunting story of a man in the grip of a painful and beautifully articulated spiritual malaise.” —Publishers Weekly

Descriere

The bestselling author of "Asylum" and a master of contemporary psychological terror returns with a riveting novel about a psychiatrist who treats trauma patients and experiences some traumas of his own.

Caracteristici

This is Patrick McGrath's biggest book since his acclaimed Asylum and will appeal to fans of Paul Auster's Leviathan and of the work of Kazuo Ishiguro and Graham Swift