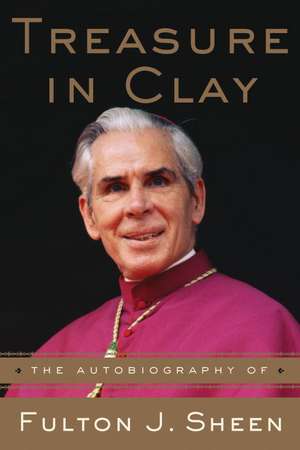

Treasure in Clay: The Autobiography of Fulton J. Sheen

Autor Fulton J. Sheen, F Sheenen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 ian 1982

Completed shortly before his death in 1979, Treasure in Clay is the autobiography of Fulton J. Sheen, the preeminent teacher, preacher, and pastor of American Catholicism.

Called “the Great Communicator” by Billy Graham and “a prophet of the times” by Pope Pius XII, Sheen was the voice of American Catholicism for nearly fifty years. In addition to his prolific writings, Sheen dominated the airwaves, first in radio, and later television, with his signature program “Life is Worth Living,” drawing an average of 30 million viewers a week in the 1950s. Sheen had the ears of everyone from presidents to the common men, women, and children in the pews, and his uplifting message of faith, hope, and love shaped generations of Catholics.

Here in Sheen’s own words are reflections from his childhood, his years in seminary, his academic career, his media stardom, his pastoral work, his extensive travels, and much more. Readers already familiar with Sheen and as well as those coming to him for the first time will find a fascinating glimpse into the Catholic world Sheen inhabited, and will find inspiration in Sheen’s heartfelt recollections. Treasure in Clay is a classic book and a lasting testament to a life that was worth living.

Preț: 102.47 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 154

Preț estimativ în valută:

19.61€ • 21.31$ • 16.49£

19.61€ • 21.31$ • 16.49£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 31 martie-14 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780385177092

ISBN-10: 0385177097

Pagini: 388

Dimensiuni: 133 x 203 x 27 mm

Greutate: 0.38 kg

Ediția:Comp & Unabrdgd.

Editura: Galilee Book

ISBN-10: 0385177097

Pagini: 388

Dimensiuni: 133 x 203 x 27 mm

Greutate: 0.38 kg

Ediția:Comp & Unabrdgd.

Editura: Galilee Book

Notă biografică

Fulton Sheen (1895 – 1979) was one of the most prominent Catholic leaders in American history. He was bishop of Rochester, national director of the Society for the Propagation of the Faith, a participant in the Second Vatican council, and television’s first religious broadcaster. He is author of numerous books, including Life of Christ, and his cause for canonization is currently under consideration.

Extras

One

It All Depends on How You Look At It

When the record of any human life is set down, there are three pairs of eyes who see it in a different light. There is the life:

1. As I see it.

2. As others see it.

3. As God sees it.

Let it be said here at the beginning that this is not my real autobiography. That was written twenty-one centuries ago, published and placarded in three languages, and made available to everyone in Western civilization.

Carlyle was wrong in saying that "there is no life of a man faithfully recorded." Mine was! The ink used was blood, the parchment was skin, the pen was a spear. Over eighty chapters make up the book, each for a year of my life. Though I pick it up every day, it never reads the same. The more I lift my eyes from its pages, the more I feel the need of doing my own autobiography that all might see what I want them to see. But the more I fasten my gaze on it, the more I see that everything worthwhile in it was received as a gift from Heaven. Why then should I glory in it?

That old autobiographical volume was like the sun. The farther I walked from it, the deeper and the longer were the shadows that stretched before my eyes: regrets, remorse and fears. But as I walked toward it, the shadows fell behind me, less awesome but still reminders of what I had left undone. But when I took the book into my hands, there were no shadows either fore or aft, but the supernal joy of being bathed in light. It was like walking directly under the sun, no mirages to solicit, no phantoms to follow.

That autobiography is the crucifix--the inside story of my life not in the way it walks the stage of time, but how it was recorded, taped and written in the Book of Life. It is not the autobiography that I tell you, but the autobiography I read to myself. In the crown of thorns, I see my pride, my grasping for earthly toys in the pierced Hands, my flight from shepherding care in the pierced Feet, my wasted love in the wounded Heart, and my prurient desires in the flesh hanging from Him like purple rags. Almost every time I turn a page of that book, my heart weeps at what eros has done to agape, what the "I" has done to the "Thou," what the professed friend has done to the Beloved.

But there have been moments in that autobiography when my heart leaped with joy at being invited to His Last Supper; when I grieved when one of my own left His side to blister His lips with a kiss; when I tried falteringly to help carry His gibbet to the Hill of the Skull; when I moved a few steps closer to Mary to help draw the thrust sword from her heart; when I hoped to be now and then in life a disciple like the disciple called "Beloved"; when I rejoiced at bringing other Magdalenes to the Cross to become the love we fall just short of in all love; when I tried to emulate the centurion and press cold water to thirsty lips; when, like Peter, I ran to an empty tomb and then, at a seashore, had my heart broken a thousand times as He kept asking over and over again in my life: "Do you love Me?" These are the more edifying moments of the autobiography which can be written as a kind of second and less authentic edition than the real autobiography written two thousand years ago.

What is contained in this edition is not the whole truth--the Scars are the whole truth. My life, as I see it, is crossed up with the crucifix. Only the two of us--my Lord and I--read it, and as the years go on we spend more and more time reading it together. What it contains will be telecast to the world on the Day of Judgment.

What you read is truth nevertheless, but on a lower level: the narrative of a jewel and its setting, the treasure and its wrapping, the lily and its pond.

How, then, do I see my life? I see it as a priest. That means I am no longer my own but at every moment of existence acting in the person of Christ. As a United States ambassador in a foreign country whether at recreation or in council chambers is always being judged as a representative of our country, so too a priest is always an ambassador of Christ. But that is only one side of the coin. The priest is still a man.

That is why the title of this autobiography is Treasure in Clay. It is taken from a letter St. Paul wrote to the Corinthians about himself and other apostles of the Lord as being no better than "pots" of earthenware to contain the treasure. The example may have been the clay lamps in which oil was put to hold light. I have chosen this text to indicate the contrast between the nobility of the vocation to the priesthood and the frailty of the human nature which houses it. We have the awesome power to act in Persona Christi, that is, to forgive the grossest of sins, to transplant the Cross of Calvary to the altar, to give divine birth to thousands of children at the baptismal font, and to usher souls on deathbeds to the Kingdom of Heaven.

But, on the other hand, we look like anyone else. We have the same weaknesses as other men, some to the bottle, or a woman, or a dollar, or a desire to be a little higher in the hierarchy of power. Each priest is a man with a body of soft clay. To keep that treasure pure, he has to be stretched out on a cross of fire. Our fall can be greater than the fall of anyone else because of the height from which we tumble. Of all the bad men, bad religious men are the worst, because they were called to be closer to Christ.

That is why it is hard for one with this calling to write an autobiography, because there is enacted the frightening tension between the dignity of his calling and the corruptibility of his clay. As Cardinal Newman wrote: "I could not even bear the scrutiny of an angel; how then can I see Thee and live? I should be seared as grass, should I be exposed to the glow of Thy Countenance." But at the very white-hot center of this tension between the divinity of the mission and the poor weak human instrumentality there is always the outpouring of the love of Christ. He never permits any of us to be tempted beyond our strength; and even in our weaknesses He loves us, for the Good Shepherd loves lost shepherds, as much as lost sheep. The tension is greatest, perhaps, for those who try to love Him with total surrender.

But the way I see my life in conformity with my vocation is different from how others might see it. That is why there are biographies as well as autobiographies. Even biographies can differ one from the other: the life of Christ that John left in his Gospel is quite different from the life that Judas would have written had he used a pen instead of a halter. Biographies generally are not written until one becomes a celebrity--or until one who is not known well enough to talk to is known well enough to talk about.

Shakespeare surmised that, in biography,

The evil that men do lives after them,

The good is oft interred with their bones.

But when it comes to writing about a bishop who is given the throne a few feet above the people, there is danger of seeing him in pomp and dignity. Again, appealing to Shakespeare:

Man, proud man

Dressed in a little brief authority,

Most ignorant of what he's most assur'd,

His glossy essence, like an angry ape,

Plays such fantastic tricks before high heaven

As make the angels weep.

When one enjoys some popularity in the world, such as the Lord has given to me in great measure, one is praised and respected even beyond desserts. As a little boy wrote to me on my eighty-fourth birthday: "I hop you have a happy birthday. I hop you will live long and I hop that one day you will be Pop."

At the end of a long life, one generally finds that there are two things said: things that are too good to be true and things that are too bad to be true. The excess is on the side of credit, which is indeed a tribute to the laity who see the priest as he is really supposed to be--"another Christ."

The Lord does not choose the best. I was not given a vocation because God, in His divine wisdom, saw that I would be better than other men. Even God's love is blind. I know thousands of men who are far more deserving of being a priest than I am. He often chooses weak instruments in order that His power might be manifested; otherwise it would seem that the good was done by the clay, rather than by the Spirit. The Lord came into Jerusalem on an ass. He can ride into New York and London and down the middle aisle of any cathedral in a human nature that is not much better. The Lord does not hold in great esteem those who are high in popularity polls: "Woe to you when all men speak well of you."

This might seem to put the Gospel in a repulsive light, but what our Lord meant was that we may begin to believe our newspaper clippings and to be carried away by what the world thinks of us. Generally, the more we accept popular estimates, the less time we spend on our knees examining conscience. The outer world becomes so full of limelight as to make us forget the light within. Praise often creates in us a false impression that we deserve it. Our reaction to it changes with the years: in the beginning one is embarrassed and flustered; then we love it while claiming that it runs off us like water off a duck's back--but the duck likes water! The latter stage is apt to end in cynicism as we wonder what the one who praises really wants.

Finally, there is my life as God sees it. Here the judgment is completely different. Man reads the face but God reads the heart. David was not chosen for his good looks, nor Elijah rejected because of his. Our Lord has a double view of us: the way He intended us to be and the way we corresponded to His grace. God took a great risk in giving us free will as parents do when they grant freedom to their children. The prophet Jeremiah offers a very beautiful story of the difference between the ideal that God has for each of us and the way we make ourselves. God writes the final epitaph--not on monuments but on hearts. I only know that those who received more talents from God will be more strictly judged. When a man has been given much, much will be expected of him; and the more a man might have had entrusted to him, the more he could be required to repay. God has given me not only a vocation, but He enriched it with opportunities and gifts, which means that He will expect me to pay a high income tax on the Final Day.

How God will judge I know not, but I trust that He will see me with mercy and compassion. I am only certain that there will be three surprises in Heaven. First of all, I will see some people there whom I never expected to see. Second, there will be a number whom I expect to be there who will not be there. And, even relying on His mercy, the biggest surprise of all may be that I will be there.

Two

The Molding of the Clay

Clay has to be molded, and that is done primarily in the family, which is more sacred than the state. The determining mold of my early life was the decision of my parents that each of their children should be well educated. This resolve was born not out of their own education, but their lack of it. My father never went beyond the third grade because his father felt he was needed on the farm. My mother had no more than an eighth-grade education at a time when there was one teacher for all the grades.

On my mother's side both my grandparents came from Croghan, a little village in County Roscommon, Ireland, near the town of Boyle. My father's father (whom I never knew because he died when I was quite small) was born in Ireland also. My father's mother, however, was born in Indiana. Unfortunately, she, too, died before I was old enough to know her.

My father, Newton Sheen, and my mother, Delia Fulton, owned a hardware store in El Paso, Illinois, about thirty miles east of Peoria. One day, my father sent the store's errand boy down to the basement for some merchandise. The boy--who later on became a banker in the town--saw his father enter the front door as he was coming back up the stairs. The boy was smoking a cigarette, which was almost anathema for a young boy in those days. Fearful of his father, he threw it under the stairs. It fell in a fifty-gallon can of gasoline and the whole business section of El Paso burned down! Perhaps to recoup the losses, and in order to earn his living, my father then moved to a farm which he had inherited from his father.

From earliest age I showed a distaste for anything associated with farm life, and my father often said that, as a young boy, I took a saw and destroyed one of the endgates of his best wagon. By this time, there were two sons in the family, I being the oldest and Joe next in line, following me by two years. I suppose that being poor creates in some a desire to be rich; but in any case, my parents' want of education begot in them a resolve that their children should be educated. So they moved to Peoria in order that I might be enrolled in St. Mary's, the parochial school there, and begin a Christian education.

It was at this point in my life that I was given the name of Fulton. It seems that I cried for almost the first two years of my mortal life. Later, as a boy, I was so embarrassed when visiting relatives and a family doctor would always begin the conversation to my mother: "Oh, this is the boy who never stopped crying." I became such a burden to my mother that her own mother and father would often relieve her tears. Jokingly, relatives and friends would say to my mother: "Oh, he's Fulton's baby." When I was enrolled in the parochial school my grandfather Fulton was asked my name and he answered: "It's Fulton." Though I had been baptized Peter in St. Mary's Church in El Paso, Illinois, I now was called Fulton. In the course of time, my brother Joe became a lawyer in Chicago, and the one next to him, Tom, became a doctor in New York, and the fourth, Al, entered industry--so the children of Newton and Delia Sheen did receive an education. Thirty or forty years later, when I was taken to a hospital in New York after collapsing in a radio studio, my brother the doctor discovered that as a child I had had tuberculosis, which produced the profuse tears, and they in turn produced calcium, which helped cure the affliction and give me a strong set of lungs. In any case, after taking the name John at Confirmation, I became Fulton John Sheen.

It All Depends on How You Look At It

When the record of any human life is set down, there are three pairs of eyes who see it in a different light. There is the life:

1. As I see it.

2. As others see it.

3. As God sees it.

Let it be said here at the beginning that this is not my real autobiography. That was written twenty-one centuries ago, published and placarded in three languages, and made available to everyone in Western civilization.

Carlyle was wrong in saying that "there is no life of a man faithfully recorded." Mine was! The ink used was blood, the parchment was skin, the pen was a spear. Over eighty chapters make up the book, each for a year of my life. Though I pick it up every day, it never reads the same. The more I lift my eyes from its pages, the more I feel the need of doing my own autobiography that all might see what I want them to see. But the more I fasten my gaze on it, the more I see that everything worthwhile in it was received as a gift from Heaven. Why then should I glory in it?

That old autobiographical volume was like the sun. The farther I walked from it, the deeper and the longer were the shadows that stretched before my eyes: regrets, remorse and fears. But as I walked toward it, the shadows fell behind me, less awesome but still reminders of what I had left undone. But when I took the book into my hands, there were no shadows either fore or aft, but the supernal joy of being bathed in light. It was like walking directly under the sun, no mirages to solicit, no phantoms to follow.

That autobiography is the crucifix--the inside story of my life not in the way it walks the stage of time, but how it was recorded, taped and written in the Book of Life. It is not the autobiography that I tell you, but the autobiography I read to myself. In the crown of thorns, I see my pride, my grasping for earthly toys in the pierced Hands, my flight from shepherding care in the pierced Feet, my wasted love in the wounded Heart, and my prurient desires in the flesh hanging from Him like purple rags. Almost every time I turn a page of that book, my heart weeps at what eros has done to agape, what the "I" has done to the "Thou," what the professed friend has done to the Beloved.

But there have been moments in that autobiography when my heart leaped with joy at being invited to His Last Supper; when I grieved when one of my own left His side to blister His lips with a kiss; when I tried falteringly to help carry His gibbet to the Hill of the Skull; when I moved a few steps closer to Mary to help draw the thrust sword from her heart; when I hoped to be now and then in life a disciple like the disciple called "Beloved"; when I rejoiced at bringing other Magdalenes to the Cross to become the love we fall just short of in all love; when I tried to emulate the centurion and press cold water to thirsty lips; when, like Peter, I ran to an empty tomb and then, at a seashore, had my heart broken a thousand times as He kept asking over and over again in my life: "Do you love Me?" These are the more edifying moments of the autobiography which can be written as a kind of second and less authentic edition than the real autobiography written two thousand years ago.

What is contained in this edition is not the whole truth--the Scars are the whole truth. My life, as I see it, is crossed up with the crucifix. Only the two of us--my Lord and I--read it, and as the years go on we spend more and more time reading it together. What it contains will be telecast to the world on the Day of Judgment.

What you read is truth nevertheless, but on a lower level: the narrative of a jewel and its setting, the treasure and its wrapping, the lily and its pond.

How, then, do I see my life? I see it as a priest. That means I am no longer my own but at every moment of existence acting in the person of Christ. As a United States ambassador in a foreign country whether at recreation or in council chambers is always being judged as a representative of our country, so too a priest is always an ambassador of Christ. But that is only one side of the coin. The priest is still a man.

That is why the title of this autobiography is Treasure in Clay. It is taken from a letter St. Paul wrote to the Corinthians about himself and other apostles of the Lord as being no better than "pots" of earthenware to contain the treasure. The example may have been the clay lamps in which oil was put to hold light. I have chosen this text to indicate the contrast between the nobility of the vocation to the priesthood and the frailty of the human nature which houses it. We have the awesome power to act in Persona Christi, that is, to forgive the grossest of sins, to transplant the Cross of Calvary to the altar, to give divine birth to thousands of children at the baptismal font, and to usher souls on deathbeds to the Kingdom of Heaven.

But, on the other hand, we look like anyone else. We have the same weaknesses as other men, some to the bottle, or a woman, or a dollar, or a desire to be a little higher in the hierarchy of power. Each priest is a man with a body of soft clay. To keep that treasure pure, he has to be stretched out on a cross of fire. Our fall can be greater than the fall of anyone else because of the height from which we tumble. Of all the bad men, bad religious men are the worst, because they were called to be closer to Christ.

That is why it is hard for one with this calling to write an autobiography, because there is enacted the frightening tension between the dignity of his calling and the corruptibility of his clay. As Cardinal Newman wrote: "I could not even bear the scrutiny of an angel; how then can I see Thee and live? I should be seared as grass, should I be exposed to the glow of Thy Countenance." But at the very white-hot center of this tension between the divinity of the mission and the poor weak human instrumentality there is always the outpouring of the love of Christ. He never permits any of us to be tempted beyond our strength; and even in our weaknesses He loves us, for the Good Shepherd loves lost shepherds, as much as lost sheep. The tension is greatest, perhaps, for those who try to love Him with total surrender.

But the way I see my life in conformity with my vocation is different from how others might see it. That is why there are biographies as well as autobiographies. Even biographies can differ one from the other: the life of Christ that John left in his Gospel is quite different from the life that Judas would have written had he used a pen instead of a halter. Biographies generally are not written until one becomes a celebrity--or until one who is not known well enough to talk to is known well enough to talk about.

Shakespeare surmised that, in biography,

The evil that men do lives after them,

The good is oft interred with their bones.

But when it comes to writing about a bishop who is given the throne a few feet above the people, there is danger of seeing him in pomp and dignity. Again, appealing to Shakespeare:

Man, proud man

Dressed in a little brief authority,

Most ignorant of what he's most assur'd,

His glossy essence, like an angry ape,

Plays such fantastic tricks before high heaven

As make the angels weep.

When one enjoys some popularity in the world, such as the Lord has given to me in great measure, one is praised and respected even beyond desserts. As a little boy wrote to me on my eighty-fourth birthday: "I hop you have a happy birthday. I hop you will live long and I hop that one day you will be Pop."

At the end of a long life, one generally finds that there are two things said: things that are too good to be true and things that are too bad to be true. The excess is on the side of credit, which is indeed a tribute to the laity who see the priest as he is really supposed to be--"another Christ."

The Lord does not choose the best. I was not given a vocation because God, in His divine wisdom, saw that I would be better than other men. Even God's love is blind. I know thousands of men who are far more deserving of being a priest than I am. He often chooses weak instruments in order that His power might be manifested; otherwise it would seem that the good was done by the clay, rather than by the Spirit. The Lord came into Jerusalem on an ass. He can ride into New York and London and down the middle aisle of any cathedral in a human nature that is not much better. The Lord does not hold in great esteem those who are high in popularity polls: "Woe to you when all men speak well of you."

This might seem to put the Gospel in a repulsive light, but what our Lord meant was that we may begin to believe our newspaper clippings and to be carried away by what the world thinks of us. Generally, the more we accept popular estimates, the less time we spend on our knees examining conscience. The outer world becomes so full of limelight as to make us forget the light within. Praise often creates in us a false impression that we deserve it. Our reaction to it changes with the years: in the beginning one is embarrassed and flustered; then we love it while claiming that it runs off us like water off a duck's back--but the duck likes water! The latter stage is apt to end in cynicism as we wonder what the one who praises really wants.

Finally, there is my life as God sees it. Here the judgment is completely different. Man reads the face but God reads the heart. David was not chosen for his good looks, nor Elijah rejected because of his. Our Lord has a double view of us: the way He intended us to be and the way we corresponded to His grace. God took a great risk in giving us free will as parents do when they grant freedom to their children. The prophet Jeremiah offers a very beautiful story of the difference between the ideal that God has for each of us and the way we make ourselves. God writes the final epitaph--not on monuments but on hearts. I only know that those who received more talents from God will be more strictly judged. When a man has been given much, much will be expected of him; and the more a man might have had entrusted to him, the more he could be required to repay. God has given me not only a vocation, but He enriched it with opportunities and gifts, which means that He will expect me to pay a high income tax on the Final Day.

How God will judge I know not, but I trust that He will see me with mercy and compassion. I am only certain that there will be three surprises in Heaven. First of all, I will see some people there whom I never expected to see. Second, there will be a number whom I expect to be there who will not be there. And, even relying on His mercy, the biggest surprise of all may be that I will be there.

Two

The Molding of the Clay

Clay has to be molded, and that is done primarily in the family, which is more sacred than the state. The determining mold of my early life was the decision of my parents that each of their children should be well educated. This resolve was born not out of their own education, but their lack of it. My father never went beyond the third grade because his father felt he was needed on the farm. My mother had no more than an eighth-grade education at a time when there was one teacher for all the grades.

On my mother's side both my grandparents came from Croghan, a little village in County Roscommon, Ireland, near the town of Boyle. My father's father (whom I never knew because he died when I was quite small) was born in Ireland also. My father's mother, however, was born in Indiana. Unfortunately, she, too, died before I was old enough to know her.

My father, Newton Sheen, and my mother, Delia Fulton, owned a hardware store in El Paso, Illinois, about thirty miles east of Peoria. One day, my father sent the store's errand boy down to the basement for some merchandise. The boy--who later on became a banker in the town--saw his father enter the front door as he was coming back up the stairs. The boy was smoking a cigarette, which was almost anathema for a young boy in those days. Fearful of his father, he threw it under the stairs. It fell in a fifty-gallon can of gasoline and the whole business section of El Paso burned down! Perhaps to recoup the losses, and in order to earn his living, my father then moved to a farm which he had inherited from his father.

From earliest age I showed a distaste for anything associated with farm life, and my father often said that, as a young boy, I took a saw and destroyed one of the endgates of his best wagon. By this time, there were two sons in the family, I being the oldest and Joe next in line, following me by two years. I suppose that being poor creates in some a desire to be rich; but in any case, my parents' want of education begot in them a resolve that their children should be educated. So they moved to Peoria in order that I might be enrolled in St. Mary's, the parochial school there, and begin a Christian education.

It was at this point in my life that I was given the name of Fulton. It seems that I cried for almost the first two years of my mortal life. Later, as a boy, I was so embarrassed when visiting relatives and a family doctor would always begin the conversation to my mother: "Oh, this is the boy who never stopped crying." I became such a burden to my mother that her own mother and father would often relieve her tears. Jokingly, relatives and friends would say to my mother: "Oh, he's Fulton's baby." When I was enrolled in the parochial school my grandfather Fulton was asked my name and he answered: "It's Fulton." Though I had been baptized Peter in St. Mary's Church in El Paso, Illinois, I now was called Fulton. In the course of time, my brother Joe became a lawyer in Chicago, and the one next to him, Tom, became a doctor in New York, and the fourth, Al, entered industry--so the children of Newton and Delia Sheen did receive an education. Thirty or forty years later, when I was taken to a hospital in New York after collapsing in a radio studio, my brother the doctor discovered that as a child I had had tuberculosis, which produced the profuse tears, and they in turn produced calcium, which helped cure the affliction and give me a strong set of lungs. In any case, after taking the name John at Confirmation, I became Fulton John Sheen.

Recenzii

PRAISE FOR TREASURE IN CLAY

“Sheen...wrote of his sixty-year priesthood, from curate to bishop, with the same ability to simultaneously entertain and elucidate that made him a media star.”—Publishers Weekly

“Sheen...wrote of his sixty-year priesthood, from curate to bishop, with the same ability to simultaneously entertain and elucidate that made him a media star.”—Publishers Weekly