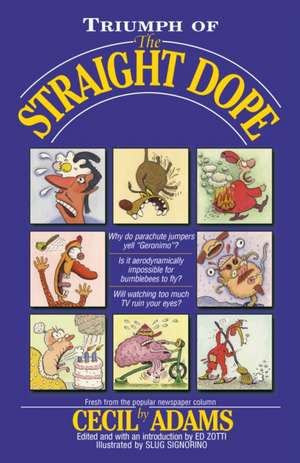

Triumph of the Straight Dope

Autor Cecil Adams Editat de Ed Zotti Ilustrat de Slug Signorinoen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 ian 1999 – vârsta de la 14 până la 18 ani

Is it aerodynamically impossible for bumblebees to fly?

Will watching too much TV ruin your eyes?

Fresh from the popular newspaper column by CECIL ADAMS!

WHAT IS CECIL ADAMS'S IQ?

"Do you want it in scientific notation? Little Ed, get out the slide rule."

--Cecil Adams

For more than a quarter of a century Cecil Adams has been courageously

attempting to lift the veil of ignorance surrounding the modern world.

Now, in his fifth book, he takes yet another stab, dissecting such classic

conundrums as

--If you swim less than an hour after eating, will you get cramps and die?

--What's the difference between a Looney Tune and a Merrie Melody?

--Can you see a Munchkin committing suicide in The Wizard of Oz?

--Was The Texas Chainsaw Massacre based on actual events?

--Did medieval lords really have "the right of the first night"?

And much more!

THE CRITICS: STILL RAVING AFTER ALL THESE YEARS!

"Trenchant, witty answers to the great imponderables."

--Denver Post

Preț: 114.09 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 171

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.84€ • 22.79$ • 18.31£

21.84€ • 22.79$ • 18.31£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 20 februarie-06 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780345420084

ISBN-10: 034542008X

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 21 mm

Greutate: 0.4 kg

Editura: BALLANTINE BOOKS

ISBN-10: 034542008X

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 21 mm

Greutate: 0.4 kg

Editura: BALLANTINE BOOKS

Notă biografică

Cecil Adams is author of The Straight Dope, More of the Straight Dope, Return of the Straight Dope, and The Straight Dope Tells All. All of Cecil's dealings with the public are handled by his editor and confidant, Ed Zotti, author of Know It All!, who has been sworn to secrecy. Consequently, little is known about Cecil's private life.

Extras

Just what does "colitis" mean? In the song "Hotel California" by the Eagles the first lines are, "On a dark desert highway, cool wind in my hair, warm smell of colitis rising up through the air." I remember I tried looking it up at a university library years ago and couldn't find the answer. I know songwriters sometimes make up words, but I didn't see a Dr. Seuss credit on the album.

--Wendy Martin, via the Internet

Uh, Wendy. It's colitas, not colitis. Colitis (pronounced koe-LIE-tis) is an inflammation of the large intestine. You're probably thinking of that famous Beatles lyric, "the girl with colitis goes by."

As for "Hotel California," you realize a lot of people aren't troubled so much by colitas as by the meaning of the whole damn song. Figuring that we should start with the general and move to the particular, I provide the following commonly heard theories:

1. The Hotel California is a real hotel located in (pick one) Baja California on the coastal highway between Cabo San Lucas and La Paz or else near Santa Barbara. In other words, the song is a hard look at the modern hospitality industry, which is plagued by guests who "check out any time [they] like" but then "never leave."

2. The Hotel California is a mental hospital. I see one guy on the Web has identified it as "Camarillo State Hospital in Ventura County between L.A. and Santa Barbara."

3. It's about satanism. Isn't everything?

4. Hotel California is a metaphor for cocaine addiction. See "You can check out any time you like but you can never leave." This comes from the published comments of Glenn Frey, one of the coauthors.

5. It's about the pitfalls of living in southern California in the 1970s, my interpretation since first listen. Makes perfect sense, and goddammit, who you going to believe, some ignorant rock star or me?

6. My fave, posted to the Usenet by Thomas Dzubin of Vancouver, British Columbia: "There was this fireworks factory just three blocks from the Hotel California ... and it blew up! Big tragedy. One of the workers was named Wurn Snell and he was from the town of Colitas in Greece. One of the workers who escaped the explosion talked to another guy ... I think it was probably Don Henley ... and Don asked what the guy saw. The worker said, "Wurn Snell of Colitas ... rising up through the air."

He's also got this bit about "on a dark dessert highway, Cool Whip in my hair." Well, I thought it was funny.

OK, back to colitas. Personally, I had the idea colitas was a type of desert flower. Apparently not. Type "colitas" into a Web search engine and you get about 50 song-lyric hits plus, curiously, a bunch of citations from Mexican and Spanish restaurant menus. Hmm, one thinks, were the Eagles rhapsodizing about the smell of some good carryout? We asked some native Spanish speakers and learned that colitas is the diminutive feminine plural of the Spanish cola, tail. Little tail. Looking for a little ... we suddenly recalled a (male) friend's guess that colitas referred to a certain feature of the female anatomy. We paused. Naah. Back to those menus. "Colitas de langosta enchiladas" was baby lobster tails simmered in hot sauce with Spanish rice. One thinks: You know, I could write a love song around a phrase like that.

Enough of these distractions. By and by, a denizen of soc.culture.spain wrote: "Colitas is little tails, but here the author is referring to 'colas,' the tip of a marijuana branch, where it is more potent and with more sap (said to be the best part of the leaves)." We knew with an instant shock of certainty that this was the correct interpretation. The Eagles, with the prescience given only to true artists, were touting the virtues of high-quality industrial hemp! (See page 129.) And to think some people thought this song was about drugs.

Our Suspicions Confirmed

This E-mail just in from Eagles management honcho Irving Azoff: "In response to your [recent] memo, in 1976, during the writing of the song 'Hotel California' by Messrs. Henley and Frey, the word 'colitas' was translated for them by their Mexican-American road manager as 'little buds.' You have obviously already done the necessary extrapolation. Thank you for your inquiry."

I knew it.

Why did Charles Manson believe that the Beatles song "Helter Skelter" was about the upcoming race war? Are there any documents that you own that say why in hell he would think this, other than the fact that he is crazy?

--J.C. from MI

I'd say the fact that he's crazy pretty well covers it. "Helter Skelter," which appeared on the Beatles' White Album, was Paul McCartney's attempt to outrock Pete Townshend of the Who. Some Beatles fans describe the song as heavy metal, which is putting it a bit strongly. But it had more energy than most McCartney compositions of the period, and the descending refrain "helter skelter" lent it an edginess that made it stick in the mind.

The song's musical qualities had very little to do with its subject matter, however. "In England, home of the Beatles, 'helter skelter' is another name for a slide in an amusement park," Manson prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi tells us in his book about the case, Helter Skelter. The Oxford English Dictionary further clarifies that a helter skelter is "a towerlike structure used in funfairs and pleasure grounds, with an external spiral passage for sliding down on a mat." Recall the opening line: "When I get to the bottom I go back to the top of the slide/Where I stop and I turn and I go for a ride." It's a joke, get it? The Rolling Stones might do this faux bad-guy thing about putting a knife right down your throat, but the ever-whimsical McCartney figured he'd rock the house singing about playground equipment.

All this went over the head of Charles Manson. He thought Helter Skelter was the coming race war and the White Album was a call to arms. If you're in a certain frame of mind you can understand some of this--e.g., the "piggies" in the tune of the same name, who need a "damn good whacking," and the sounds of gunfire in "Revolution 9." But to think that the line "you were only waiting for this moment to arise" in the song "Blackbird" was an invitation to black people to start an insurrection ... sure, Charlie. Whatever you say. Now put down that gun.

In your book The Straight Dope you were asked whether John Wayne had ever served in the military. You said no--that though Wayne as a youth had wanted to become a naval officer, "during World War II, he was rejected for military service." However, it may be more interesting than that. According to a recent Wayne bio, for all his vaunted patriotism, Wayne may actually have tried to stay out of the service.

--Virgiejo, via AOL

John Wayne, draft dodger? Oh, what delicious (if cheap) irony! But that judgment is a little harsh. As Garry Wills tells the story in his book John Wayne's America: The Politics of Celebrity (1997), the Duke faced a tough choice at the outset of World War II. If he wimped out, don't be so sure a lot of us wouldn't have done the same.

At the time of Pearl Harbor, Wayne was 34 years old. His marriage was on the rocks, but he still had four kids to support. His career was taking off, in large part on the strength of his work in the classic Western Stagecoach (1939). But he wasn't rich. Should he chuck it all and enlist? Many of Hollywood's big names, such as Henry Fonda, Jimmy Stewart, and Clark Gable, did just that. (Fonda, Wills points out, was 37 at the time and had a wife and three kids.) But these were established stars. Wayne knew that if he took a few years off for military service, there was a good chance that by the time he got back he'd be over the hill.

Besides, he specialized in the kind of movies a nation at war wanted to see, in which a rugged American hero overcame great odds. Recognizing that Hollywood was an important part of the war effort, Washington had told California draft boards to go easy on actors. Perhaps rationalizing that he could do more good at home, Wayne obtained 3-A status, "deferred for [family] dependency reasons." He told friends he'd enlist after he made just one or two more movies.

The real question is why he never did so. Wayne cranked out thirteen movies during the war, many with war-related themes. Most of the films were enormously successful, and within a short time the Duke was one of America's most popular stars. His bankability now firmly established, he could have joined the military, secure in the knowledge that Hollywood would welcome him back later. He even made a halfhearted effort to sign up, sending in the paperwork to enlist in the naval photography unit commanded by a good friend, director John Ford.

But he didn't follow through. Nobody really knows why; Wayne didn't like to talk about it. A guy who prided himself on doing his own stunts, he doesn't seem to have lacked physical courage. One suspects he just found it was a lot more fun being a Hollywood hero than the real kind. Many movie-star soldiers had enlisted in the first flush of patriotism after Pearl Harbor. As the war ground on, slogging it out in the trenches seemed a lot less exciting. The movies, on the other hand, had put Wayne well on the way to becoming a legend. "Wayne increasingly came to embody the American fighting man," Wills writes. In late 1943 and early 1944 he entertained the troops in the Pacific theater as part of a USO tour. An intelligence big shot asked him to give his impression of Douglas MacArthur. He was fawned over by the press when he got back. Meanwhile, he was having a torrid affair with a beautiful Mexican woman. How could military service compare with that?

In 1944 Wayne received a 2-A classification, "deferred in support of [the] national ... interest." A month later the Selective Service decided to revoke many previous deferments and reclassified him 1-A. But Wayne's studio appealed and got his 2-A status reinstated until after the war ended.

People who knew Wayne say he felt bad about not having served. Some think his guilty conscience was one reason he became such a superpatriot later. The fact remains that the man who came to symbolize American patriotism and pride had a chance to do more than just act the part, and he let it pass.

Some Warner Brothers cartoons are called Looney Tunes; some are called Merrie Melodies. What's the difference between the two?

--Arnold Wright Blan, Sugar Hill, Georgia

My initial idea was to tell you that Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies reflected the dichotomy between the Apollonian and Dionysian impulses or, if you will, the classical and romantic modes of creative expression. However, even I couldn't keep up a crock like that. Then I figured, This is Hollywood, there's gotta be some mercenary angle to it. Sure enough. While there were differences between Tunes and Melodies, the main reason for having two separate series was that's the way they'd structured the deal.

At the outset, the two series were made under separate agreements between Warner Brothers and producer Leon Schlesinger, using different production teams. The Looney Tunes series, created by Hugh Harman and Rudolph Ising, was introduced in 1930. A blatant rip-off of Disney's Silly Symphonies series, each Looney Tune was required to have one full chorus from a song from a Warner feature film. The cartoons typically were run prior to the main feature at theaters, and the idea was that they would promote WB product. (Among other things, the company had various music-publishing concerns.) The schedule called for a new cartoon approximately once a month.

The Tunes were immediately popular, and the following year Warner commissioned Schlesinger to produce a sister series called Merrie Melodies, which also appeared monthly. (The volume of cartoons fluctuated in later years, but the two series were always produced in roughly equal numbers.) At this point Harman and Ising divided responsibilities, with Harman in charge of Looney Tunes and Ising handling the Melodies. Merrie Melodies also featured Warner songs, but where Tunes had regular characters, Melodies for the most part were one-shots, without continuing characters. Another difference was that Melodies were shot in color starting in 1934, while Tunes stayed black-and-white.

In my younger days I would have stopped right there. However, if there's one thing I've learned in this business it's that you can never overestimate the anality of film and animation buffs. Someone would inevitably have made the following observations:

1. By the late 1930s regular characters started appearing in Merrie Melodies, and by the 1940s the same characters were appearing interchangeably in both series.

2. Some of Schlesinger's production people switched freely back and forth between series.

3. Looney Tunes were shot in color after 1943.

4. Leon Schlesinger retired in 1944 and Warner Brothers began doing cartoon production in-house, after which time (and probably long before which time) there was no reason to maintain any distinction between Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies. The two separate series titles persisted because, you know, there'd always been two separate series titles, and they had different theme music, and why rock the boat?

5. Nyaah nyaah nyaah nyaah.

So childish. Nonetheless, the fact remains that the difference between Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies was pretty much an existential thing. On a practical level it prepares us to deal with the many meaningless distinctions of life--e.g., Pepsi versus Coke, MasterCard versus Visa, and the Democrats versus the GOP. The Saturday-morning 'toons just a way to kill time? Please. They're Introduction to Reality 101.

While leafing through my Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock N' Roll, I came upon the horrifying fact that Chuck Berry's "Johnny B. Goode," the song that started rock, peaked at #8 in 1958. What seven forgettable songs were deemed better than this classic?--Tim Ring, Montreal, Quebec

Cecil loves the classics as much as the next guy, but let's not get carried away. "Johnny B. Goode" did not start rock. Even "Maybellene," Chuck Berry's first hit (#5 in 1955), did not start rock, although it was one of the earliest rock tunes to make it big. If you've got to pick one tune that put rock 'n' roll over the top, I still say it's got to be Bill Haley's "Rock Around the Clock," which became--admittedly not right away--a monster hit, selling 22 million copies. And let's not forget the righteous contribution of Alan Freed, the Cleveland DJ who attached the term "rock 'n' roll" to the emerging new sound in 1954.

"Johnny B. Goode" peaked at #8 on the Billboard charts on May 5, 1958. My assistant Little Ed, in his ceaseless drive to muck up my holy work, threw out all my old Billboards last spring, but I still have the monthly composite chart for May 1958 compiled by Dave McAleer, on which "Johnny B. Goode" ranks #11. It got beaten out by the following tunes, some of which, God help me, I cannot remember, and some of which, God help me, I can't forget: 1) "All I Have to Do Is Dream," Everly Brothers; 2) "Witch Doctor," David Seville; 3) "Wear My Ring Around Your Neck," Elvis Presley; 4) "Twilight Time," Platters; 5) "He's Got the Whole World (In His Hands)," Laurie London; 6) "Return to Me," Dean Martin; 7) "Book of Love," Monotones; 8) "Looking Back/Do I Like It," Nat "King" Cole; 9) "Tequila," Champs; 10) "Oh Lonesome Me/I Can't Stop Lovin' You," Don Gibson.

Don't feel sorry for Chuck Berry, though. He had two other Top 40 hits in 1958, "Sweet Little Sixteen" (peaked at #2) and "Carol" (#18), plus several others that made it into the Top 100. And he definitely had the last laugh. In a career that included such gems as "Roll Over Beethoven" (#29, 1956) and "No Particular Place to Go" (#10, 1964), his only #1 hit was the inane "My Ding-a-Ling," which held the top spot for two weeks in 1972.

There was a news story a few years back about a jazz musician who died and was found to be a woman after living her life as a man. She was married and had three grown children who refused to believe their father was a woman. No one I ask remembers this. Do you?

--SMENGI, via AOL

You think I could forget the story of Billy Tipton? Yes, she lived as a man from age 21 till the day she died at age 74. Yes, her three sons (all adopted) never suspected a thing. But that's not the bizarre part. She lived with five women in succession, all of them attractive, a couple of them knockouts. She had intercourse with at least two of them and, who knows, maybe all five. But of the three we know about in detail, none tumbled to the fact that her husband was a woman (one figured it out later). At first you might think: Man, I thought my spouse was oblivious. But the more charitable view is that they were taken in by one of the great performances of all time.

We know as much as we know about Billy thanks to a newly published biography by Diane Wood Middlebrook, Suits Me: The Double Life of Billy Tipton. Middlebrook reports that Dorothy Lucille Tipton decided to become Billy Tipton in 1935, ostensibly because it was the only way an aspiring jazz musician could get work in an almost exclusively male business. The transformation wasn't all that tough. Billy's face was boyish, and her figure was more Coke can than Coke bottle. (She had sizable breasts but no waist.) A sheet wrapped around her chest, men's clothes, and a bit of padding in the crotch, and she easily passed. In fact, Billy was positively handsome; women thought he was a doll. A talented pianist, horn player, and tenor, he quickly found a gig with a band.

At first Billy was strictly a cross-dresser, making no great effort to conceal her femaleness during her off hours. She lived with a woman with the unusual name of Non Earl Harrell, in what other musicians assumed was a lesbian relationship. Initially they were based in Oklahoma City, but by 1940 they had moved to Joplin, Missouri, then an entertainment center. There Billy began to masquerade as a male full-time, a pose he would adopt for the rest of his life.

Billy and Non Earl broke up in 1942. After a liaison of some years with a singer named June, Billy took up with Betty Cox, a pretty 19-year-old with a striking figure. The two stayed together for seven years, during which time they had what Betty recalled as a passionate heterosexual relationship, including intercourse. She even thought she'd had a miscarriage once. How could you share a bed with someone for seven years and not realize he was a she? Breathtaking naïveté had to be part of it, plus the fact that, as an accomplished entertainer who was 13 years Betty's senior, Billy called the shots. They made love only in the dark. Billy never removed his underwear and wore a jockstrap that Betty later speculated was fitted with a "prosthesis." He wore massive chest bindings at all times, supposedly for an old injury. He would not let himself be touched below the waist or disturbed in the bathroom. Betty also may have been a bit distracted. Acquaintances said she went out with other men while she was with Billy, and while she appears to have been genuinely fond of him, in some ways this may have been a marriage of convenience for both.

A turning point in Billy's life came in 1958. He had his own trio and a growing reputation, and a new hotel in Reno wanted to hire his group as its house band. He seemed on the verge of, if not the big time, at least a fairly high-profile career. But Billy declined. Instead he took a job as a booking agent in Spokane, Washington, playing music on the side. Middlebrook thinks he feared fame would lead to discovery and decided he'd gone as far as he dared.

At this point Billy was living with a sometime call girl, but in the early '60s he left her for a beautiful but troubled stripper named Kitty Kelly. She claimed she and Billy never had sex, but in other respects they lived a stereotypical suburban life. They adopted three boys, but neither could handle the kids during adolescence, and after a bitter quarrel in 1980 Billy moved into a trailer with his sons. From there it was all downhill. The boys split, his income dried up, and he spent his last years broke. Refusing to see a doctor despite failing health, he collapsed and died in 1989. The paramedics who were trying to revive him uncovered the truth. Death must have come as a relief; he had been on stage nearly 54 years.

In movies, when someone lands a punch there's this nifty slappy sound that real punches just don't make. What is that sound?

--Adam S., New Haven, Connecticut

Welcome to the world of "Foley artists," the unsung geniuses who create the larger-than-life sound effects that make a flick come alive. For a good face punch, a Foley artist might hit a piece of raw meat with his fist, maybe wearing a tight leather glove for enhanced smackiness. I'm told rib cuts are particularly good to use because they have bones to give a crunchy effect. Then again, maybe the Foley artist will just punch himself--hard. The beauty of Foley--named after Jack Foley, chief sound effects guru at Universal for many years--is that nobody's telling you exactly what you have to do. All that counts is that it works on-screen.

Foley art is made necessary by the fact that 1) you need "action noise" (i.e., more than just the actors talking) to make a movie scene seem real, and 2) miking the entire stage or location during shooting just isn't practical. Even if it were, real-life sounds often don't have the oomph the big screen demands. In addition, dubs for foreign markets often require that a sound track be created completely from scratch. So Foley artists add sound in postproduction. The most basic type of Foley consists of one or more people walking around in a well-miked "Foley pit" filled with gravel, sand, loose audiotape (to mimic the sound of crunching leaves), etc., to re-create the sounds of the actors in motion. They do this while watching the movie with the sound off, synchronizing their movements with the action on the screen. This requires a good sense of timing and rhythm, and maybe for that reason a lot of Foley artists are also musicians.

Some Foley effects have been around since the dawn of the talkies--for example, walking on cornstarch in a burlap bag to create the sound of crunching snow. Another time-tested technique is drawing a paddle full of nails across a piece of glass to create the sound of branches scratching on a windowpane.

Other sound effects are of more recent vintage. Foley artist Greg Mauer told us he was recently working on a vampire flick that had a scene in which a character's guts get pulled out. Greg used raw chicken, which he likes because you get a nice moist sound he describes as "slimy." For a simple broken bone there's nothing like the crisp sound of snapping a stalk of celery or a chicken bone.

Not all Foley is fake. If a scene calls for somebody falling, a lot of Foley artists figure there's no substitute for actually falling. Same with walking on sand. But if you need the sound of 150 people running around, no way you're actually going to cram 150 people into the Foley pit. Instead you have maybe three Foley artists laying down a half-dozen tracks. Mix 'em together and voilà--crowd noise.

As you might surmise in this age of high-tech special effects, cinema sound can involve lots of fancy enhancements you'd need a degree in computer science to understand. But it's good to know there's still a place in the movie business for guts and red meat.

While watching a recent interview with Emmylou Harris, I was horrified when a member of the audience asked a rather personal question about Gram Parsons ("Why did Gram Parsons kill himself at such a young age?"). Ms. Harris handled the question gracefully and moved on to other, more pertinent topics (the sad state of commercial country music), but the question got me thinking. I've been a fan of Parsons's music but don't really know all that much about him as a person, other than that he died young and there was some controversy surrounding his death. Can you fill me in?

--Jamie D., East Lansing, Michigan

Glad to. Some guys lead weird lives, some guys have weird deaths. Not everybody has a weird cremation.

Gram Parsons has become something of a cult figure in the music business. He never hit it big, and few outside a small circle remember him now. But people who ought to know say he was one of the pioneers behind the country-rock phenomenon of the late 1960s and early '70s. A member of the Byrds for a short time, Parsons was the creative force behind their 1968 country album, Sweetheart of the Rodeo, which many consider a classic. He went on to form the Flying Burrito Brothers and later invited then unknown Emmylou Harris out to L.A. to sing on his solo album, GP (1973), helping to launch her career. He hung out with the Rolling Stones (his influence can be heard on several cuts from Exile on Main Street) and had a big impact on Elvis Costello, Linda Ronstadt, Tom Petty, and the Eagles. Remember New Riders of the Purple Sage and Pure Prairie League? They owed a lot to Parsons. He's received many posthumous honors and musical tributes; Emmylou Harris is working on a tribute album now, 25 years after his death. Best of all, he was born Ingram Cecil Connor III (Parsons came from his stepfather), and you gotta love a guy with a name like that.

Parsons wasn't a suicide, but he killed himself, all right. Blessed with charm and cash (his mother's family had made a pile in the citrus business), he got into booze and drugs early. In September 1973 he finished recording an album and went with some friends to an inn at Joshua Tree National Monument, one of his favorite places. The group spent much of the day by the pool getting tanked. By evening Gram looked like hell and went to his room to sleep. Later, on their way out for some food, his friends were unable to rouse him, so they left, returning a little before midnight. By that time Parsons was pretty far gone. Taken to a hospital, he was pronounced dead shortly after midnight on September 19. A lab analysis found large amounts of alcohol and morphine in his system; apparently the combination killed him. News coverage of his demise was eclipsed by the death of Jim Croce around the same time. Parsons was 26 years old.

So far, your typical live-fast-die-young story. Then it gets strange. Before his death Parsons had said that he wanted to be cremated at Joshua Tree and have his ashes spread over Cap Rock, a prominent natural feature there. But after his death his stepfather arranged to have the body shipped home for a private funeral, to which none of his music buddies were invited. Said buddies would have none of it. Fortified by beer and vodka, they decided to steal Parsons's body and conduct their own last rites.

Having ferreted out the shipping arrangements, Phil Kaufman (Parsons's road manager) and another man drove out to the airport in a borrowed hearse, fed the poor schmuck in charge of the body a load of baloney about a last-minute change of plans, signed the release "Jeremy Nobody," and made off with Parsons's remains. They bought five gallons of gas, drove 150 miles to Joshua Tree, and by moonlight dragged the coffin as close to Cap Rock as they could. Kaufman pried open the lid to reveal Parsons's naked cadaver, poured in the gas, and tossed in a match. A massive fireball erupted. The authorities gave chase but, as one account puts it, "were encumbered by sobriety," and the desperadoes escaped.

The men were tracked down a few days later, but there was no law against stealing a body, so they were charged with stealing the coffin or, as one cop put it, "Gram Theft Parsons." (Cops are such a riot.) Convicted, they were ordered to pay $750, the cost of the coffin. What was left of Parsons was buried in New Orleans.

So, youthful high jinks or breathless stupidity? All I know is, I'd want my friends to show a little more enterprise keeping me alive than torching my corpse.

A friend pointed out a haunting secret tucked away in the depths of The Wizard of Oz. Way in the background at the end of the scene where the angry trees shake apples onto Dorothy, the Tin Man, and the Scarecrow, you can see a man who is supposedly hanging himself. As the trio dances off on the Yellow Brick Road singing "We're Off to See the Wizard," you can catch a glimpse of this man supposedly setting out a block, hanging himself, and lastly kicking the block out with his foot. Although this image is real enough to give you chills, it could conceivably be a fake. Is it? If it is real, then why did the director keep it in the movie? What is the story of this man?

--James Leary, via the Internet

You may say: Cecil, why are you spending time on this obviously brain-damaged question? Come on, tell me you wouldn't jump at a chance to call up Munchkins. Besides, I looked at the movie, and you know what? There is something strange going on.

The alleged suicide comes not at the end of the apple-tossing scene (at which point the Tin Woodsman hasn't yet appeared) but roughly eight minutes later, after the Wicked Witch has made a surprise visit and then vanished in a cloud of orange smoke. Resolving to be brave, Dorothy, the Scarecrow, and the now-present Tin Man link arms, march out to the Yellow Brick Road, and dance around a bit. In the background at this point, in about the center of the frame, one can see a dimly lit stand of trees. Something is moving near these trees, but it's hard to make out what. The trio sashays off toward the rear of the set, in the general direction of the trees, then veers and exits stage right. Just as they leave the frame, a limblike thing near the trees swings up briefly into a horizontal position, then drops again. A suicide kicking the ladder out from beneath himself? Or--you have to consider all the possibilities--the leg of a naked woman in the throes of a passionate embrace?

You can guess what I saw. However, the most common version of the legend has it that this is the on-camera suicide of a despairing Munchkin. (Runner-up: a despairing, or just accident-prone, stagehand. Some claim the victim had recently been fired.)

The Straight Dope research department, known for its dogged investigative skills, tracked down Stephen Cox, author of an entertaining volume titled The Munchkins of Oz (1996). Cox, who interviewed more than 30 Munchkins to collect stories about the making of the movie, dismissed the suicide story and hinted at an alternative theory, which we'll get to in a moment. He also put us in touch with Mickey Carroll, 78, one of 13 Munchkins still alive today (out of an original 124). Carroll said he'd first heard the story about five years before but also thought it was bunk. "We were on the set for two months," he said. "I think I would have known if someone committed suicide." (Incidentally, several Munchkins did get fired--one for threatening his wife with a gun--but apparently none was the suicidal type.)

Well, OK. But then what are we seeing? Cox points out that if you look closely during the eight or nine minutes preceding the "suicide," i.e., from just before Dorothy and the Scarecrow encounter the apple-tossing trees, you can spot a large bird strolling around the set--maybe a crane or a stork. (For much of the time it appears to be tethered near the house on which the Wicked Witch perches.) Presumably the bird is supposed to provide atmosphere, but basically all it does is pop into the frame at odd moments. Reviewing the "suicide" with this in mind, we instantly realize: it's the stupid bird pecking the ground and then flapping its wings! Though, this being Hollywood Babylon and all, a naked woman's leg can't be entirely ruled out. But the adult in us knows the truth.

Recently on your America Online site you posted your old column about Rock'n Rollen Stewart, the guy who used to hold up those "John 3:16" signs at sports events. You may be interested to know that Stewart is now serving a life sentence in jail.

--Name withheld, via AOL

Yowsah. I lost track of Rollen after talking to him in 1987. At the time he struck me, and I'd say most people, as a harmless if obsessed flake. Shows how wrong you can be. A few years later Stewart went completely off his nut, staged a series of bombings, and wound up in prison after a bizarre kidnapping stunt. The whole story is told in The Rainbow Man/John 3:16, a documentary by San Francisco filmmaker Sam Green. If you doubt that too much TV is bad for you, you won't after seeing this flick.

Stewart's problems started during his childhood in Spokane, Washington. His parents were alcoholics. His father died when Rollen was seven. His mother was killed in a house fire when he was 15. That same year his sister was strangled by her boyfriend. A shy kid, Rollen got into drag racing in high school, married his first love, and opened a speed shop. But his wife soon left him. Crushed, he sold the shop and moved to a mountain ranch, where he became a marijuana farmer, tried to grow the world's longest mustache, and watched a lot of TV.

In 1976, looking for a way to make his mark, Rollen conceived the idea of becoming famous by constantly popping up in the background of televised sporting events. Wearing a multicolored Afro wig (hence the nickname "Rainbow Man"), he'd carry a battery-powered TV to keep track of the cameras, wait for his moment, then jump into the frame, giving the thumbs-up and grinning. Rollen figured he'd be able to parlay his underground (OK, background) celebrity into a few lucrative TV gigs and retire rich. But except for one Budweiser commercial, it didn't happen.

Feeling depressed after the 1980 Super Bowl, he began watching a preacher on the TV in his hotel room and found Jesus. He began showing up at TV events wearing T-shirts emblazoned with "Jesus Saves" and various Bible citations, most frequently John 3:16 ("For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son," etc.). Later accompanied by his wife, a fellow Christian he married in the mid-80s, he spent all his time traveling to sports events around the country, lived in his car, and subsisted on savings and donations. He guesses he was seen at more than a thousand events all told.

This brings us to the late '80s. By now Rollen had gotten his 15 minutes of fame and was the target of increasing harassment by TV and stadium officials. His wife left him, saying he had choked her because she held up a sign in the wrong location. His car was totaled by a drunk driver, his money ran out, and he wound up homeless in L.A. Increasingly convinced that the end was near, Rollen decided to create a radically different media character. He set off a string of bombs in a church, a Christian bookstore, a newspaper office, and several other locations. Meanwhile, he sent out apocalyptic letters that included a hit list of preachers, signing the letters "the Antichrist." Rollen says he wanted to call attention to the Christian message, and while this may seem like a sick way to go about it, it wasn't much weirder than waving signs in the end zone at football games. In any case, no one was hurt in the bombings, which mostly involved stink bombs.

On September 22, 1992, believing the Rapture was only six days away and having prepared himself by watching TV for 18 hours a day, Stewart began his last "presentation." Posing as a contractor, he picked up two day laborers in downtown L.A., then drove to an airport hotel. Taking the men up to a room, he unexpectedly walked in on a chambermaid. In the confusion that followed he drew a gun, the two men escaped, and the maid locked herself in the bathroom. The police surrounded the joint, and Rollen demanded a three-hour press conference, hoping to make his last national splash. He didn't get it. After a nine-hour siege the cops threw in a concussion grenade, kicked down the door, and dragged him away.

About to be given three life sentences for kidnapping, Rollen threw a tantrum in the courtroom and now blames everything on a society that's "bigoted toward Jesus Christ." A cop who negotiated with him by phone during the hotel standoff had a better take on it: "With all due respect, maybe you look at a little bit too much TV." For info on the Rainbow Man documentary, write Sam Green, 2437 Peralta St., Suite C, Oakland, CA 94607.

From The Straight Dope Message Board

Subj: The four races of men

From: Jeuvohed

I know about Caucasoid, Mongoloid, and Negroid. What's the fourth?

From: Bermuda999

Hemorrhoid.

From: DMG550

Paranoid?

From: JonRandall

Herculoid.

From: FixedBack

Celluloid.

From: PUNditOK

Polaroid. While polaroids tend to be odd sized when compared with other races, there is no doubt that their rapid development gives them an evolutionary edge.

Textul de pe ultima copertă

For more than a quarter of a century Cecil Adams has been courageously attempting to lift the veil of ignorance surrounding the modern world. Now, in his fifth book, he takes yet another stab, dissecting such classic conundrums as

-- If you swim less than an hour after eating, will you get cramps and die?

-- What's the difference between a Looney Tune and a Merrie Melody?

-- Can you see a Munchkin committing suicide in The Wizard of Oz?

-- Was The Texas Chainsaw Massacre based on actual events?

-- Did medieval lords really have "the right of the first night"?

-- If you swim less than an hour after eating, will you get cramps and die?

-- What's the difference between a Looney Tune and a Merrie Melody?

-- Can you see a Munchkin committing suicide in The Wizard of Oz?

-- Was The Texas Chainsaw Massacre based on actual events?

-- Did medieval lords really have "the right of the first night"?

And much more!

Descriere

The newest collection of Adams' wacky and witty columns syndicated by the "Chicago Reader". Illustrations.