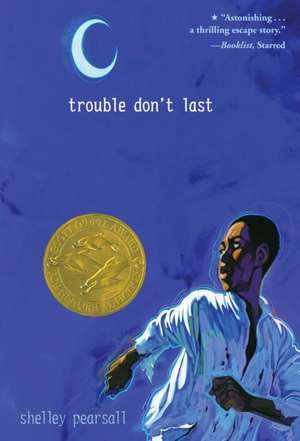

Trouble Don't Last

Autor Shelley Pearsallen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 noi 2003 – vârsta de la 8 până la 12 ani

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

Sunshine State Young Reader's Award (2005), Nevada Young Readers' Award (2004), Rebecca Caudill Young Readers Book Award (2005)

The journey north seems much more frightening than Master Hackler ever was, and Samuel’s not sure what freedom means aside from running, hiding, and starving. But as they move from one refuge to the next on the Underground Railroad, Samuel uncovers the secret of his own past—and future. And old Harrison begins to see past a whole lifetime of hurt to the promise of a new life—and a poignant reunion—

in Canada.

In a heartbreaking and hopeful first novel, Shelley Pearsall tells a suspenseful, emotionally charged story of freedom and family. Trouble Don't Last includes a historical note and map.

Preț: 50.46 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 76

Preț estimativ în valută:

9.66€ • 10.11$ • 7.99£

9.66€ • 10.11$ • 7.99£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780440418115

ISBN-10: 0440418119

Pagini: 239

Dimensiuni: 148 x 178 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.17 kg

Editura: DELL YEARLING

ISBN-10: 0440418119

Pagini: 239

Dimensiuni: 148 x 178 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.17 kg

Editura: DELL YEARLING

Notă biografică

A former middle school teacher and historian, Shelley Pearsall is now working on her next historical novel and leading writing workshops for children.

Trouble Don’t Last is her first novel.

Pearsall did extensive research while writing Trouble Don’t Last and traveled to towns along the escape route–including crossing the Ohio River in a boat and visiting a community in Chatham, Ontario, another destination for runaway slaves. “I’ve found that learning about history in an imaginative way often sticks with students longer than review questions in a text-book,” says Pearsall.

AUTHOR'S NOTE

The Underground Railroad is a familiar American story. It is filled with dramatic tales of secret rooms, brave abolitionists, and midnight journeys. But sometimes the real heroes of the story–the runaways themselves–are left in the background. What did they think and feel as they tried to reach freedom? What was their journey like? Whom did the runaways trust and whom did they fear? This book grew from my wondering about these questions. . . .

In my research, I learned that the Underground Railroad was not a clear, organized network that led runaways from the South to the North. Actually, the term referred to any safe routes or hiding places used by runaways–so there were hundreds, even thousands of "underground railroads."

Most runaways traveled just the way that Samuel and Harrison did–using whatever temporary hiding places or means of transportation they could find. As the number of actual railroad lines increased throughout the country in the 1850's, some runaways even hid on railroad cars when travelling from one place to another. They called this "riding the steam cars" or "going the faster way."

I also discovered that runaways were not as helpless or ill-prepared as they are sometimes portrayed. Historical records indicate that many slaves planned carefully for their journey. They brought provisions such as food and extra clothing with them. Since transportation and guides could cost money, some slaves saved money for their escape, while others, like Samuel and Harrison, received money from individuals they met during their journey.

White abolitionists and sympathetic religious groups like the Quakers aided many runaways on the Underground Railroad. However, free African Americans played an equally important role. They kept runaways in their homes and settlements, and served as guides, wagon drivers, and even decoys.

In fact, the character of the river man is based on the real-life story of a black Underground Railroad guide named John P. Parker. Like the River Man, John Parker was badly beaten as a young slave, and so he never traveled anywhere without a pistol in his pocket and a knife in his belt. During a fifteen year period, he ferried more than 400 runaways across the Ohio River, and a $ 1000 reward was once offered for his capture. After the Civil War, he became a successful businessman in Ripley, Ohio, and patent several inventions.

I am often asked what other parts of the novel are factual. The gray yarn being sent as a sign? The baby buried below the church floor? Lung fever? Guides named Ham and Eggs?

The answer is yes. Most of the events and names used in this novel are real, but they come from many different sources. I discovered names like Ordee Lee and Ham and Eggs in old letters and records of the Underground Railroad. The character of Hetty Scott is based on a description I found in John Parker's autobiography. The heart-wrenching tale of Ordee Lee saving the locks of hair from his family comes from a slave's actual account. However, I adapted all of this material to fit into the story of Samuel and Harrison–so time periods and locations have often been changed.

One of the most memorable aspects of writing this book was taking a trip to northern Kentucky and southern Ohio in late summer. To be able to describe the Cornfield Bottoms and the Ohio River, I walked down to the river late at night to see what it looked like and how it sounded in the darkness. To be able to write about Samuel's mother, I stood on a street corner in Old Washington, Kentucky, where slaves were once auctioned. I even stayed in houses that had been in existence during the years of the Underground Railroad.

I chose the southern Ohio and northern Kentucky region for my setting since it had been a very active area for the Underground Railroad. I selected the year 1859 because Congress passed a national law called the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, which affected everyone involved in the Underground Railroad. Severe penalties such as heavy fines and jail time awaited anyone–white or black–who helped or harbored runaway slaves anywhere in the United States after 1850.

The law also required people to return runaway slaves to their owners, even if the runaways were living in free states like Ohio. African-Americans like August and Belle, who had papers to prove their freedom, were safe from capture even though their lives were sometimes restricted by local and state "black laws." However, runaway slaves were only safe if they left the country and went to places like Canada or Mexico. That is why Samuel and Harrison had to journey all the way to Canada to be free in 1859.

So, if you visited Canada today, would you still find a peaceful place called Harrison's Pond? And is there a tumbledown farmhouse somewhere in Kentucky with an old burying-ground for slaves nearby?

Harrison's Pond and Blue Ash, Kentucky, are places in my imagination, but there are many other places to visit with solemn footsteps and remember. I hope that you will.

–Shelley Pearsall

From the Hardcover edition.

Trouble Don’t Last is her first novel.

Pearsall did extensive research while writing Trouble Don’t Last and traveled to towns along the escape route–including crossing the Ohio River in a boat and visiting a community in Chatham, Ontario, another destination for runaway slaves. “I’ve found that learning about history in an imaginative way often sticks with students longer than review questions in a text-book,” says Pearsall.

AUTHOR'S NOTE

The Underground Railroad is a familiar American story. It is filled with dramatic tales of secret rooms, brave abolitionists, and midnight journeys. But sometimes the real heroes of the story–the runaways themselves–are left in the background. What did they think and feel as they tried to reach freedom? What was their journey like? Whom did the runaways trust and whom did they fear? This book grew from my wondering about these questions. . . .

In my research, I learned that the Underground Railroad was not a clear, organized network that led runaways from the South to the North. Actually, the term referred to any safe routes or hiding places used by runaways–so there were hundreds, even thousands of "underground railroads."

Most runaways traveled just the way that Samuel and Harrison did–using whatever temporary hiding places or means of transportation they could find. As the number of actual railroad lines increased throughout the country in the 1850's, some runaways even hid on railroad cars when travelling from one place to another. They called this "riding the steam cars" or "going the faster way."

I also discovered that runaways were not as helpless or ill-prepared as they are sometimes portrayed. Historical records indicate that many slaves planned carefully for their journey. They brought provisions such as food and extra clothing with them. Since transportation and guides could cost money, some slaves saved money for their escape, while others, like Samuel and Harrison, received money from individuals they met during their journey.

White abolitionists and sympathetic religious groups like the Quakers aided many runaways on the Underground Railroad. However, free African Americans played an equally important role. They kept runaways in their homes and settlements, and served as guides, wagon drivers, and even decoys.

In fact, the character of the river man is based on the real-life story of a black Underground Railroad guide named John P. Parker. Like the River Man, John Parker was badly beaten as a young slave, and so he never traveled anywhere without a pistol in his pocket and a knife in his belt. During a fifteen year period, he ferried more than 400 runaways across the Ohio River, and a $ 1000 reward was once offered for his capture. After the Civil War, he became a successful businessman in Ripley, Ohio, and patent several inventions.

I am often asked what other parts of the novel are factual. The gray yarn being sent as a sign? The baby buried below the church floor? Lung fever? Guides named Ham and Eggs?

The answer is yes. Most of the events and names used in this novel are real, but they come from many different sources. I discovered names like Ordee Lee and Ham and Eggs in old letters and records of the Underground Railroad. The character of Hetty Scott is based on a description I found in John Parker's autobiography. The heart-wrenching tale of Ordee Lee saving the locks of hair from his family comes from a slave's actual account. However, I adapted all of this material to fit into the story of Samuel and Harrison–so time periods and locations have often been changed.

One of the most memorable aspects of writing this book was taking a trip to northern Kentucky and southern Ohio in late summer. To be able to describe the Cornfield Bottoms and the Ohio River, I walked down to the river late at night to see what it looked like and how it sounded in the darkness. To be able to write about Samuel's mother, I stood on a street corner in Old Washington, Kentucky, where slaves were once auctioned. I even stayed in houses that had been in existence during the years of the Underground Railroad.

I chose the southern Ohio and northern Kentucky region for my setting since it had been a very active area for the Underground Railroad. I selected the year 1859 because Congress passed a national law called the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, which affected everyone involved in the Underground Railroad. Severe penalties such as heavy fines and jail time awaited anyone–white or black–who helped or harbored runaway slaves anywhere in the United States after 1850.

The law also required people to return runaway slaves to their owners, even if the runaways were living in free states like Ohio. African-Americans like August and Belle, who had papers to prove their freedom, were safe from capture even though their lives were sometimes restricted by local and state "black laws." However, runaway slaves were only safe if they left the country and went to places like Canada or Mexico. That is why Samuel and Harrison had to journey all the way to Canada to be free in 1859.

So, if you visited Canada today, would you still find a peaceful place called Harrison's Pond? And is there a tumbledown farmhouse somewhere in Kentucky with an old burying-ground for slaves nearby?

Harrison's Pond and Blue Ash, Kentucky, are places in my imagination, but there are many other places to visit with solemn footsteps and remember. I hope that you will.

–Shelley Pearsall

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

TROUBLE

Truth is, trouble follows me like a shadow.

To begin with, I was born a slave when other folks is born white. My momma was a slave and her momma a slave before that, so you can see we are nothing but a family of trouble. Master sold Momma before I was even old enough to remember her, and two old slaves named Harrison and Lilly had to raise me up like I was one of their own, even though I wasn't. Then, when I was in my eleventh year, the old slave Harrison decided to jump into trouble himself, and he tried to run away.

Problem was, I had to go with him.

THE BROKEN PLATE

It all started on a just-so day in the month of September 1859, when I broke my master's plate while clearing the supper table. I tried to tell Lilly that if Master Hackler hadn't taken a piece of bread and sopped pork fat all over his old plate, I wouldn't have dropped it.

But Lilly kept her lips pressed tight together, saying nothing as she scraped the vegetable scraps into the hog pails.

"And Young Mas Seth was sticking his foot this-away and that-away, tryin to trip me up," I added.

Lilly didn't even look at me, just kept scraping and scraping with her big, brown hands.

"Maybe it was a spirit--could be Old Mas Hackler's dead spirit--that got ahold of me right then and made that plate fly right outta my hands."

Lilly looked up and snorted, "Spirits. If Old Mas Hackler wanted to haunt this house, he'd go an' turn a whole table on its end, not bother with one little china plate in your hands." She pointed her scraping knife at me. "You gotta be more careful, Samuel, or they gonna sell you off sure as anything, and I can't do nothin to help you then. You understand me, child?"

"Yes'm," I answered, looking down at my feet. Every time Lilly said something like this to me, which was more often than not, it always brought up the same picture in my head. A picture of my momma. She had been sold when I was hardly even standing on my own two legs. Right after the Old Master Hackler had died. Lilly said that selling off my momma paid for his fancy carved headstone and oak burying box, but I'm not sure all that is true.

In my mind, I could see my momma being taken away in the back of Master's wagon, just the way Lilly told me. Her name was Hannah, and she was a tall, straight-backed woman with gingerbread skin like mine. Lilly said that she was wearing a blue-striped headwrap tied around her hair, and she was leaning over with her head down in her hands when they rode off. The only thing Lilly knew was that they took her to the courthouse in Washington, Kentucky, to sell her.

After my momma had gone, it had fallen on Lilly's shoulders to raise me as if I was her own boy, even though she wasn't any relation of mine and she'd already had two sons and four daughters, all sold off or dead. But she said I had more trouble in me than all six of her children rolled up together. "I gotta be on your heels day and night," she was always telling me. "And even that don't keep the bad things from happening."

When she was finished with the hog pails, Lilly came over to me. "How's that chin doin?" She lifted the cold rag I'd been holding and looked underneath. "Miz Catherine got good aim, I give her that."

After I had broken the china plate, Master Hackler's loud, redheaded wife, Miz Catherine, had flung her table fork at me. "You aren't worth the price of a broken plate, you know that?" she hollered, and sent one of the silver forks flying. Good thing I had sense enough not to duck my head down, so it hit right where she was aiming, square on my chin. Even though it stung all the way up to my ear, I didn't make a face. I was half-proud of myself for that.

"You pick up every little piece," Miz Catherine had snapped, pointing at the floor. "Every single piece with those worthless, black fingers of yours, and I'll decide what to do about your carelessness."

After that, Lilly had come barreling in to save me. She had helped me sweep up the white shards that had flown all over, and she told Miz Catherine that she would pay for the plate. Master usually gave Lilly a dollar to keep every Christmas. "What you think that plate cost?" Lilly asked Miz Catherine as she swept.

"How much do you have?" Miz Catherine sniffed.

"Maybe $4 saved up."

"Then I imagine it will cost you $4."

So the redheaded devil Miz Catherine had taken most of Lilly's savings just for my broken plate--although, truth was, Lilly really had $6 tucked away. And she had given me a banged-up chin. But, as Lilly always said, it could have been worse.

Then we heard Master Hackler's heavy footsteps coming down the hall. He walks hard on his heels, so you can always tell him from the others.

"You be quiet as a country graveyard," Lilly warned. "And gimme that cloth." Quick as anything, she snatched the cloth from my chin and began wiping a plate with it.

"Still cleaning up from supper?" Master Hackler said, peering around the doorway. "Samuel's made you mighty slow this evening, Lilly."

"Yes, he sho' has." Lilly kept her head down and wiped the plates in fast circles. "But I always git everything done, you know. Don't sleep a wink till everything gits done."

From the Hardcover edition.

Truth is, trouble follows me like a shadow.

To begin with, I was born a slave when other folks is born white. My momma was a slave and her momma a slave before that, so you can see we are nothing but a family of trouble. Master sold Momma before I was even old enough to remember her, and two old slaves named Harrison and Lilly had to raise me up like I was one of their own, even though I wasn't. Then, when I was in my eleventh year, the old slave Harrison decided to jump into trouble himself, and he tried to run away.

Problem was, I had to go with him.

THE BROKEN PLATE

It all started on a just-so day in the month of September 1859, when I broke my master's plate while clearing the supper table. I tried to tell Lilly that if Master Hackler hadn't taken a piece of bread and sopped pork fat all over his old plate, I wouldn't have dropped it.

But Lilly kept her lips pressed tight together, saying nothing as she scraped the vegetable scraps into the hog pails.

"And Young Mas Seth was sticking his foot this-away and that-away, tryin to trip me up," I added.

Lilly didn't even look at me, just kept scraping and scraping with her big, brown hands.

"Maybe it was a spirit--could be Old Mas Hackler's dead spirit--that got ahold of me right then and made that plate fly right outta my hands."

Lilly looked up and snorted, "Spirits. If Old Mas Hackler wanted to haunt this house, he'd go an' turn a whole table on its end, not bother with one little china plate in your hands." She pointed her scraping knife at me. "You gotta be more careful, Samuel, or they gonna sell you off sure as anything, and I can't do nothin to help you then. You understand me, child?"

"Yes'm," I answered, looking down at my feet. Every time Lilly said something like this to me, which was more often than not, it always brought up the same picture in my head. A picture of my momma. She had been sold when I was hardly even standing on my own two legs. Right after the Old Master Hackler had died. Lilly said that selling off my momma paid for his fancy carved headstone and oak burying box, but I'm not sure all that is true.

In my mind, I could see my momma being taken away in the back of Master's wagon, just the way Lilly told me. Her name was Hannah, and she was a tall, straight-backed woman with gingerbread skin like mine. Lilly said that she was wearing a blue-striped headwrap tied around her hair, and she was leaning over with her head down in her hands when they rode off. The only thing Lilly knew was that they took her to the courthouse in Washington, Kentucky, to sell her.

After my momma had gone, it had fallen on Lilly's shoulders to raise me as if I was her own boy, even though she wasn't any relation of mine and she'd already had two sons and four daughters, all sold off or dead. But she said I had more trouble in me than all six of her children rolled up together. "I gotta be on your heels day and night," she was always telling me. "And even that don't keep the bad things from happening."

When she was finished with the hog pails, Lilly came over to me. "How's that chin doin?" She lifted the cold rag I'd been holding and looked underneath. "Miz Catherine got good aim, I give her that."

After I had broken the china plate, Master Hackler's loud, redheaded wife, Miz Catherine, had flung her table fork at me. "You aren't worth the price of a broken plate, you know that?" she hollered, and sent one of the silver forks flying. Good thing I had sense enough not to duck my head down, so it hit right where she was aiming, square on my chin. Even though it stung all the way up to my ear, I didn't make a face. I was half-proud of myself for that.

"You pick up every little piece," Miz Catherine had snapped, pointing at the floor. "Every single piece with those worthless, black fingers of yours, and I'll decide what to do about your carelessness."

After that, Lilly had come barreling in to save me. She had helped me sweep up the white shards that had flown all over, and she told Miz Catherine that she would pay for the plate. Master usually gave Lilly a dollar to keep every Christmas. "What you think that plate cost?" Lilly asked Miz Catherine as she swept.

"How much do you have?" Miz Catherine sniffed.

"Maybe $4 saved up."

"Then I imagine it will cost you $4."

So the redheaded devil Miz Catherine had taken most of Lilly's savings just for my broken plate--although, truth was, Lilly really had $6 tucked away. And she had given me a banged-up chin. But, as Lilly always said, it could have been worse.

Then we heard Master Hackler's heavy footsteps coming down the hall. He walks hard on his heels, so you can always tell him from the others.

"You be quiet as a country graveyard," Lilly warned. "And gimme that cloth." Quick as anything, she snatched the cloth from my chin and began wiping a plate with it.

"Still cleaning up from supper?" Master Hackler said, peering around the doorway. "Samuel's made you mighty slow this evening, Lilly."

"Yes, he sho' has." Lilly kept her head down and wiped the plates in fast circles. "But I always git everything done, you know. Don't sleep a wink till everything gits done."

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

* “This memorable portrayal . . . proves gripping from beginning to end.”–Starred, Publishers Weekly

* “A thrilling escape story, right until the last chapter.”–Starred, Booklist

“Strong characters and an innovative, suspenseful plot distinguish Pearsall’s first novel . . . A compelling story.”–School Library Journal

“One of the best underground railroad narratives in recent years . . . This succeeds as a suspenseful historical adventure.”–Kirkus Reviews

“Pearsall’s heartbreaking, yet hopeful story provides a fine supplement to lessons on slavery.”–Teacher Magazine

AWARDS

The 2003 Scott O’ Dell Award for Historical Fiction

A Booklist Top 10 First Novel

A Booklist Top Ten Historical Fiction for Youth

From the Hardcover edition.

* “A thrilling escape story, right until the last chapter.”–Starred, Booklist

“Strong characters and an innovative, suspenseful plot distinguish Pearsall’s first novel . . . A compelling story.”–School Library Journal

“One of the best underground railroad narratives in recent years . . . This succeeds as a suspenseful historical adventure.”–Kirkus Reviews

“Pearsall’s heartbreaking, yet hopeful story provides a fine supplement to lessons on slavery.”–Teacher Magazine

AWARDS

The 2003 Scott O’ Dell Award for Historical Fiction

A Booklist Top 10 First Novel

A Booklist Top Ten Historical Fiction for Youth

From the Hardcover edition.

Descriere

Samuel, an 11-year-old Kentucky slave, and Harrison, the elderly slave who helped raise him, attempt to escape to Canada via the Underground Railroad in this acclaimed novel that includes historical notes and a map.

Premii

- Sunshine State Young Reader's Award Nominee, 2005

- Nevada Young Readers' Award Nominee, 2004

- Rebecca Caudill Young Readers Book Award Nominee, 2005

- Nutmeg Book Award Nominee, 2006

- Georgia Children's Book Award Nominee, 2005

- Jefferson Cup Honor Book, 2003

- Scott O Dell Award for Historical Fiction Winner, 2003

- Massachusetts Children's Book Award Nominee, 2005