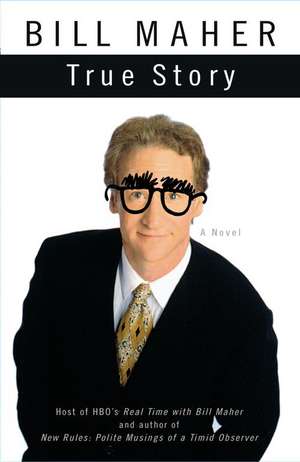

True Story: A Novel

Autor Bill Maheren Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 sep 2005

Preț: 113.51 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 170

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.72€ • 22.68$ • 17.94£

21.72€ • 22.68$ • 17.94£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 25 martie-08 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780743291354

ISBN-10: 0743291352

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 140 x 214 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Colecția Simon & Schuster

ISBN-10: 0743291352

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 140 x 214 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Colecția Simon & Schuster

Cuprins

Contents

Foreword

The Act You're Not Good Enough to See

More Green, Asshole

It's a Living Hell, but It's a Living

Show Me the Most Beautiful Woman in the World, and Somewhere There's a Guy Who's Tired of Fucking Her

Good Evening, Ladies and Geniuses

Love Is When You Don't Feel Shitty After You Come

The Work Isn't Bad -- but the Hour!

No Set, No Hamburger

Loyalty Is a One-way Street

The Nice-Ass Act of 1980

You Better Be a Winner in This Business, Because if You're Not, It's Shit

It's Easy to Do Great, It's Hard to Be Great

When Opportunity Knocks, All Some People Do Is Complain About the Noise

People: The Problem That Won't Go Away

I Dreamed I Went to See Mort Sahl, and He Was Doing Dog-and-Cat Material

When You Can't Light the Joint, You're Stoned Enough

The Power of Negative Thinking

The Sweet Stench of Success

Epilogue: The Future Isn't What It Used to Be

Extras

Chapter One: The Act You're Not Good Enough to See

Five comedians sat on a train. They were Dick, Shit, Fat, Chink, and Buick, so pseudonymed for their specialities de fare: Dick, who did dick jokes; Shit, who did shit jokes; Fat, who did fat jokes; Chink, who made fun of the way Oriental people spoke; and Buick, the observationalist, whom everyone called Buck, and so he came to be called Buck.

"Hey, get down off there!" ejaculated the conductor, and the giggling colleagues dismounted and took their rightful places inside the gleaming trispangled Amtrak Minuteman, bound for Trenton, Philadelphia, Wilmington, Baltimore, and Washington, D.C., towns where comedy was king and the audience peasants.

Near the back of the train, the comedians found a suitable enclave where three could face two and sprawled inside it. Fat took up two seats alongside his mentor, Dick, while the Damon and Pythias of comedy, Shit and Buck, sandwiched their protégé, Chink, on the opposing bench. The boys were dressed in the casual attire of the day: sneakers, Sasson jeans, sweatshirts, button-downs, and almost-leather jackets or blue hooded parkas. Except for Buck, who enjoyed the distinction of always dressing in a sports jacket and tie. They could have passed for any other five young white men who were completely out of their minds.

After the train pulled out of Penn Station, Shit got up to use the bathroom and then returned to his seat completely naked. The other boys laughed at the sight of him, although certainly not as hard as they would have laughed if it was the first time they'd seen him do such a thing. It was the first time for the other passengers, however -- but since they were New Yorkers, they probably had seen naked people in public before, probably that day. What they didn't know was that Shit and his friends were not actually dangerous, just comedians -- young comedians at that -- and playing was simply their day job.

Amtrak conductors dreaded groups of young comedians. Sometimes comedians could cohabit for a while in an enclosed area, but more often than not, play-fighting would get out of hand or one of them would attempt to pick something off another's fur and cause a yelp, or drop a rock on his head, and pretty soon the conductor would have to come by and distract them with bananas. This quintet counted itself more mature than most young comics, which is a little like saying absolutely nothing at all.

It was difficult, in fact, even to measure maturity among comedians by any of the usual societal yardsticks; certainly, age was not a factor. Shit and Dick -- who, in fairness, had outgrown their nicknames, earned during those first few panicky months of stand-up, when mention of those subjects was the only way they knew to ensure the steady oxygen of laughter -- were the eldest, at twenty-nine and thirty-five. But Shit, as worldly as he was -- and he was -- just liked to get naked. He was especially fond of walking into the men's room of a nightclub when one of his friends was onstage, then emerging sans attire for a casual stroll back to the bar. Of course, the comic onstage would have to stop Shit to ask if he hadn't forgotten something, at which point Shit would feign embarrassment and hasten back to the loo, only to reemerge with a drink in his hand and a thanks for the reminder. Not that trains and nightclubs were the only places where Shit liked to get naked: bachelor parties, double dates, hotel rooms, Yankee Stadium -- any place where other comedians were around to appreciate it, and the chance for arrest minimal, would do.

The chance for arrest on the train was getting a little stronger as Shit remained nude in his seat, but Dick was in the middle of a story, so Shit's arrest, if it came, would have to wait. Especially since the story was about Shit and Dick and another comedian getting naked the week before at an all-girl Catholic school in upstate New York, where the trio had been hired to perform.

"You didn't tell me about that," Buck whined.

"Do I have to tell you every time it happens?" Shit joshed. Still, Buck was a little hurt.

"So we walk in," Dick continued, "and there's two nuns and another woman -- not a nun but, you know, nunlike -- and they were all real nervous that we were gonna say something improper or do something like, Christ, I don't know, get naked or something."

"Why did they book you in the first place?" Fat asked.

"Who knows, shut up," Dick said quickly, but then smiled at his idolator. "Anyway, they didn't want us anywhere near the girls, so right away they hustle us down into this underground rec room with a lot of pictures of Jesus on the walls and a Ping-Pong table."

"Jesus loved Ping-Pong. He invented that Chinese grip," Buck offered.

"Although for some reason he's better known for other things," Shit added.

"They had Ping-Pong leagues back then -- the National and the Aramaic," Chink topped, with -- to no one's surprise -- the better joke.

"Anyway," Dick tracked, "they put us down there and tell us to stay put until it's time to do the show."

The boys were laughing already, because they knew the punchline.

"I had to." Shit smiled, and everyone nodded sympathetically, as one might for a more normal addiction, like gambling or defecating on glass coffee tables.

"But I didn't have to!" Dick shouted with a big laugh. "Except now I'm the only one with my clothes on, so -- "

"Peer pressure," Buck said.

"Exactly -- I mean, hey, what am I, not gonna get naked? No. So then the two nuns and the other chick come back, and these boneheads are playing Ping-Pong -- "

"Naked?" Fat asked.

"Have you been listening to the story?" Shit asked him.

"Yeah, naked," Dick scolded Fat. "Naked, okay? We were naked, this is a naked story. We're naked. And then the nuns come in -- the nuns were not naked, did I make that clear? -- and they see two guys playing Ping-Pong, and their dicks are flopping around, and I'm standing on a chair over the net like I'm judging!"

Everybody howled at that. Then Fat asked: "Who won?"

More howling. More big passenger-alarming howling, which made the conductor come by, and he was howling mad. But Shit had talked his way out of nakeder spots than this, and he toddled off to the bathroom to get dressed. When he returned, though, Shit was in a decidedly fouler mood than when he'd left, which may have been due to the restrictiveness of clothing or just because he liked descending into fouler moods.

"Mind if I eat while you smoke?" he snarled at Dick and Buck, who had lit up just as Shit removed the foil on his Amtrak-microwaved lunch.

"Easy, pal," said Buck. "God, you're as ornery as..."

"As a man stuck for a metaphor?" Shit countered.

"Boy, you're in a mood," the normally apolitical Chink interposed. "What's eatin' ya?"

"Comedy, boys. Comedy is eating me alive."

With that the others sang out in ridicule of Shit, condemning him for the negative attitude he was now imposing upon their jolly sojourn. They all liked to perpetuate the myth amongst themselves, and especially among civilians, that they were special members of society by virtue of their exemption from all accouterments of the rat race -- i.e., alarm clocks, regular hours, long days, bosses, offices, or the need to concentrate on anything for more than a few seconds. They wore the deadly sin of sloth like a badge of honor, and they relished the chance run-in with childhood friends who'd listen, mouth agape, to the description of a life comprised of recess.

But Shit wasn't buying it today. He bullishly pressed on with a discussion of reality.

"We're being exploited," he said. "They're filling that room every night of the week, getting a five-dollar cover and a two-drink minimum, and we're getting cab fare."

Shit was referring to The Club, the premier Manhattan showcase club on the Upper East Side, where the boys were among forty or so young comedians and comediennes presently getting their acts together. On this particular Friday afternoon, however, they were taking those acts on the road, and on the road -- well, the wages sucked there, too: $250 a weekend for the headliner, $150 for the middle act, $75 for the MC.

But at least now, in 1979, there was a road. Veterans like Dick and Shit, who'd already been at this game for four years, remembered when the only places for a young comic to get onstage were the handful of showcase clubs in New York and L.A. These hot spots, of which The Club was currently the hottest, presented a score of comedians every night, offering them exposure in the country's media capitals and a place to "work out" in exchange for their services, gratis. But as the decade drew to a close, a major new trend in the comedy boom was catching fire: the local comedy club. In cities all across the country, a new vaudeville was slouching to be born. Restaurant basements, hotel lounges, old coffeehouses -- even storefronts -- were being converted into clubs where two or three of these young comedians from New York or L.A. could be brought in each weekend to perform stand-up comedy. It was a trend that fed on itself: Encouraged by the expanding number of young comics available, clubs opened up by the score, and encouraged by all the places to work, hundreds of young men and women began to quit their day jobs.

So what wasn't to like?

To Buck, the recent comedy boom was the ultimate in bad luck. Because he was not part of a trend! He was one of the ones who was born to do it! He would have been a comedian in any era, and curse the luck that he came of age just as every asshole in America who had ever gotten a laugh at a fraternity party was now crowding the field. For decades, to be a comedian had meant you were literally one in a million, as there were certainly no more than two hundred professional comedians in the whole country. But now, just as he was ready to fulfill his lifelong dream, comedians were positively pullulating, breeding like mosquitoes after a wet spring in these stagnant pools they called comedy clubs. Buck laughed every time Johnny Carson brought a new comedian on The Tonight Show with the standard comedy-is-the-hardest-commodity-in-our-business-to-find introduction.

Hardest commodity to find? You could barely swing a dead cat nowadays without hitting some dickhead who called himself a comedian!

And the more comedians there were, the more the bargaining power of each descended.

"How many seats in the Washington club?" Shit continued, still on his high horse, "Three hundred? Same with Philly. And they're collecting five or six at the door, plus drinks, times four shows. You figure it out."

"You're just pissed because you're middling for me," Buck kidded, with a mischievous glint in his eye.

"Blow me," Shit responded, with absolutely no glint.

Shit, Buck, and Dick, you see, were on a mission of mercy this weekend, helping the novice members of the group, Chink and Fat, secure their very first out-of-town gigs, as MCs in Baltimore and Wilmington, respectively. Unlike at The Club, the MC job in an out-of-town club was the least important, consisting mainly of warming up the crowd for fifteen minutes, then introducing the middle act and the headliner, who performed the bulk of the real comedy for the evening. Thus the task of local MC was normally handled by someone local -- even, at times, by a noncomedian, like the owner of the club or a hostess or Gallagher. But Buck and Shit had persuaded the owner of Shennanagins, the Baltimore club, to let Chink get his feet wet on the road in this manner, and in return for this favor, they had agreed to co-headline, thereby ensuring that the show would at least have two veteran acts should Chink prove to be a disaster. Dick, being perhaps the strongest and most in-demand performer currently working in the New York comedy pool, was not asked to make a similar concession -- not that Buck and Shit should have been asked to, either. But if the owner of Shennanagins, Harvey Karrakarrass, had given a comedian something for nothing, he would have faced possible disciplinary action from the Schmucks' Association, to which all club owners belonged.

And, in truth, Buck and Shit were happy to do it: They loved Chink and believed in him. Moreover, they enjoyed doing good, almost as much as they enjoyed the idea that they were doing good. Children of the sixties, Shit and Buck held forth on the train about the new humanity alive at The Club -- how different it was from the bad old days there! Why, in days gone by, the senior acts barely spoke to the rookies, and certainly never gave them a helping hand. But then a revolution of kindness swept over the comic landscape behind its charismatic leader, Shit. Upon gaining his own stature at The Club, Shit reached out to the tyros who came along after him. One of them was Buck, who'd arrived on the scene only a year and a half ago -- not that you'd know it by the way he carried himself. Buck was the kind of guy who could have headlined only twice before in his life and make it sound for all the world as if he was a grizzled veteran. And since he had only headlined twice before, this talent came in handy.

Now, if he only had an act.

An act would have really been helpful a few months earlier, when Buck did his second headlining gig, in Montreal. The owner there wanted an hour from the headliner, and Buck assured him an hour would be no problem. But in truth, an hour was quite a problem, because Buck did not have an hour of material. He did not have a half hour of material, but with a liberal sprinkling of "Where you from?"s with an uncommonly receptive audience, he had been able to clock in close enough to the usual forty-five-minute headliner finish line to pass muster on his first headlining gig, at Shennanagins.

So Buck went to Montreal feeling pretty cocky -- quite a feat for a comedian who was 90 percent attitude and 10 percent act. Of course, a formula like that was right at home in the Big Apple: One colleague had already suggested that Buck bill himself as "the act you're not good enough to see." Buck enjoyed that. He liked having a reputation, even if it was a bad one.

And he didn't want to lose it. So when he got back to New York and everyone asked how things had gone up in Canada, he said they had gone well -- referring, apparently, to timely air service, pleasant hotel accommodations, and delightful sightseeing in the day.

As for the shows, he had suffered only a bit less horribly than the crowds who had had to watch him that weekend -- watch him die four slow, painful deaths. Nothing in his past experience as a comedian -- and almost all of it to that point had been pretty tough -- had prepared him for that. At The Club, yes, the first year had been a nightmare onstage, but every comedian's first year is a nightmare: going on for three drunks at two in the morning, desperately trying to find a distinctive voice, and being rudely awakened to the fact that having been a funny guy all your life is a world apart from being a professional comedian. But at least at The Club you were just one comic in a nightly parade, and the worst beating never lasted more than twenty minutes. But in Montreal, there he was, fifteen minutes into an hour show, and pretty much wad-shot of material.

And no closing bit! The Jordache jeans commercial -- which he "parodied" by sticking his ass out -- did not run in Canada. The biggest laugh Buck got in Montreal that weekend came from his unintentionally mispronouncing the name of the renegade Quebecois prime minister, René Levesque.

Onstage those nights, Buck thought about stealing from his friends -- who would know, it's Canada -- but he had too much pride for that. He even had too much pride to get off at forty-five or fifty or fifty-five, for crying out loud! How much more merciful that would have been for all concerned, not least the audience. Sitting through Buck was like watching an insect that suffers the misfortune of being only half stomped under someone's heel. He writhed and stammered and got hostile atop a little wooden platform in a small basement that had a liquor license while people despised him in two languages.

Buck was not a comedian who bombed gracefully. It was just so hard for him to say nothing when a good joke died. That was all he ever had to do -- say nothing and go on to the next one; the crowd wouldn't even have realized a joke had been told, and they would have still liked him. What could be easier than to just shut up?

Except for one thing: It hurt. To Buck, an unrequited joke was like offering someone a gift and having it thrown back in your face.

That, and one other tiny, little thing: They were wrong! They, sitting there, staring at him as if it were his fault! To say nothing would be acceding to that misconception -- and what kind of weenie takes upon himself the sins of others?

Jesus Christ?

Oh, Him.

At night in the hotel room, Buck cried and thought about something from Greek History 201, some character named Silenus, who told somebody in some play or book or something: "You ask what is best for you? Nothingness. To never have been born. To not be."

Well, hey -- who needs to listen to a gloomy gus like that? Especially since, other than Montreal, things had finally started going well for Buck. Just the fact that he was working out of town proved that he was finally "on the raft": that was the image that kept going through Buck's mind all through that first year at The Club, when he wanted so badly to pull himself out of the intolerable nobody-newcomer sea and get on board with the dozen or so regulars, like Shit and Dick. Their support sustained him in those trying times -- it meant so much to have their respect, to know they thought of him as a contender and not a pretender -- but it still wasn't being one of them. It wasn't being part of the elite cadre, who went on at a decent hour any night they came in and who treated each other like peers and who did real paying gigs around the city, for fifty bucks here, seventy-five there, and sometimes, on weekends out of town, for even more, enough to finally start earning their living from comedy.

From comedy! What a rush that was, to actually be making your living from this! Maybe even to be despised by the waiters at the Blue Spoon diner: that was the ultimate sign of arrival, because the actors who waited tables at the Blue Spoon hated the comedians who ate there -- you could see it in their eyes and by the way they threw the food at them -- because actors had to work a real job until they hit pay dirt, whereas comedians were finaglers who knew how to survive without busing tables for Greeks. The more the actor-waiters hated the comics, the more the comedians loved it. Oh, how wonderful that would be, Buck thought -- to be someone waiters hated and threw food at!

But to move up at The Club was an ordeal even for so ambitious a comer as Buck. There was something of an old-boy network in place, and the dozen or so spots in prime time (after ten and before one, or between the time the crowd warmed up and burned out) went to the same comics every night, the ones who'd been there for three or five or even seven years. At The Club, seniority counted.

Seniority really pissed Buck off. This was show business, he thought -- not the Ford motor plant. How could they keep putting up the same people, the same people who obviously weren't going anywhere or else they'd have been there by now?

Buck had a point about that. Some of the guys on the raft really weren't that talented. Buck wanted to whisper that opinion to Dick or to another supportive colleague, Norma, because they were the reigning MCs at The Club and as such had the power to choose who went on -- but he hesitated. That is, he paused for half a second before saying it.

"He rambles on so much before the punchline," Buck might say with a cringing disdain about some poor act who couldn't hear him because he was busy onstage.

"Yeah," Dick would giggle. "And after."

Damn, you just couldn't denigrate another comedian behind his back enough for it to have any impact. Everybody bitched about everybody, so nobody really listened.

Eventually, though, perseverance paid off for Buck one Friday night. The other off-the-raft comics didn't even come in on the weekends because, unlike the weeknights, the Friday-Saturday lineups were prescheduled, so there wasn't even a chance for a rookie to get on -- unless somebody didn't show up. For months this was what Buck had been hoping for -- that some comic with a scheduled spot would be unable to find a cab or would oversleep or, if it had to be, would get bludgeoned to death on the subway.

When it finally happened (the comedian, thank God, survived the bludgeoning), Buck at long last got his chance in prime time. He was nervous and he was raw and he still had a lot of bad habits. But Buck was right about one thing: He was born to do it, and that night he proved it.

After the show, Buck went home to his shithole studio apartment on West 49th Street and exulted, just sat up all night and exulted. He was on the raft. He'd broken through, and it was a feeling that compared to only two other moments in his life -- the day he came into the Little League championship game as a relief pitcher and saved it for his team before the whole town, and the night during sophomore year in high school after his first successful date, when he walked home in such a stupor that he overshot his own house by half a mile.

Buck smiled and thought about those two moments and now this third one.

Then he stopped exulting: Twenty-four years old, and I can count only three great moments in my life?

Jesus, this show business shit better pay off.

"I see Ted Kennedy's going to announce today."

Shit leaned back against the Amtrak-brown upholstery and spread The New York Times before him.

"Throwing his hat into the river, is he?" Dick asked.

"Illegal spritz," Buck announced, using the term that meant a comic was committing the faux pas of deploying stage material in a social setting.

"Get outta here," Dick answered. "I don't do political stuff."

"Nobody does anymore," Shit lamented.

"I do," Buck protested, perhaps referring to his insightful routine about the choice in the last election being akin to someone asking, "If you had to, what would you rather eat, shit or puke?"

"I mean nobody does it exclusively, like Mort Sahl," Shit explained.

"Who?" Fat wanted to know.

"Kids today," said Shit, shaking his head. "It's gonna be him and Reagan."

Oh, thought Fat: Mort Sahl would be running against Reagan.

"You think Kennedy'll beat Carter for the nomination?" Buck asked Shit.

"Oh yeah. The Democrats can't resist nominating a Kennedy. Will Rogers said, 'I don't belong to an organized party, I'm a Democrat.'"

"I hope he didn't open with it," Dick snickered.

"Why do you hate the Kennedys so much?" Buck asked Shit. "I never understand that -- you're Irish, Catholic, charming, witty, arrogant. You grew up in Boston. Is it just that you think you should have been a Kennedy?"

"They're just horrible people. Snot-nosed rich kids on an ego trip."

Buck bridled: "So? You can't do good for people if you're on an ego trip? Isn't there such a thing as an ego trip for good? A fucking snotty-ass Park Avenue surgeon, okay -- but he's brilliant, his ego trip is saving lives: 'Saved another one today, honey. They didn't think it could be done, but luckily I was around.' I mean, he's a dick, but he saves lives."

"So why does he have to be a dick about it?" Shit objected.

"Why? Who the fuck knows. Maybe because he wouldn't have the confidence to cut open your chest if he wasn't. You take away all the people who do important things because they're dicks, who'd be left to run things?"

"So this is your we-need-the-dicks-to-run-things theory," Shit mocked with a gentle smile.

"Are you familiar with the no-room-at-the-inn syndrome?" Buck shot back.

"No, but I am familiar with the no-room-service-at-the-inn syndrome. That's where you have to go down to the coffee shop for incense and myrrh, which is just as well, because room-service myrrh is usually wildly overpriced," Shit joked.

"No, it means the world does not want a powerful birth. When they know a Jesus is coming into the world, there's never any room at the inn."

"Maybe they were remodeling that week," Dick kidded.

"And you're saying that's why they killed the Kennedys?" Shit asked.

"No, I wasn't, but now that you mention it, that's exactly right. It's always the people that give hope who get shot -- Lincoln, King, the Kennedys."

"McKinley," Fat said, surprising everyone.

"Ah yes, McKinley," Shit said. "Gave every kid in America hope, 'cause they figured if he could grow up to be president, everybody had a shot."

"Ted Kennedy," Chink piped up. "His brother was a hero because he smashed his boat during the war, this guy drives a car into a river. Close, Ted, real close, but it's gotta be a boat. There's gotta be some kinda war goin' on."

"That's so funny," Buck pronounced. "You gotta do that."

"He speaks in material," Shit added.

"Do we have to talk about politics?" Fat asked, pissed that once again Chink had scored with the big boys.

"Everything's politics," Shit said. "Talking about us getting paid what we deserve, that's politics."

"So stop talking about it." Dick laughed.

"You know, the reason we don't get paid at The Club," Buck rejoined, unable to forgo the argument he and Shit had already rehearsed a dozen times, "is because The Club is a place to work out, not to work. It's a trade-off. They use us, and we use them to get our act together. If they paid us real money, we'd be obligated to do our best set every time. We couldn't experiment."

"Oh, come on," Shit returned. "How much experimenting is really going on in there? Everybody's so afraid they'll lose their place at the trough, they do their best set every time anyway."

"I don't," Buck said.

"You don't have a best set," Dick teased.

"No, you need a guitar for that," Buck came back, implying that Dick's use of a musical instrument adulterated the purity of straight monologue.

But Dick was genuinely ungored. Most comics were thin-skinned and easily goreable, but not Dick. He was hard to gore, no matter how many brightly colored sharp sticks one stuck into his back.

"That place is our studio," Buck continued. "Stand-up comedy is an art form. You don't pay the artist to go to class and learn shading and perspective."

"We need a union," Shit stated flatly, and then launched into his speech about how the club owners were scum and how the comedians could break their exploitative lock if only they would band together.

But the comedians did not want to talk politics on this afternoon, so Shit's jeremiad was quickly hushed. Dick especially was bored by the subject because he was -- and would be the first to admit that he was -- still a little boy. Not that this wasn't true of most comedians, but with Dick it was more literal. He was a little boy who continued to enjoy all the pleasures of little boydom -- pinball, video games, comic books, cartoons -- although none of those pleasures came close to supplying the fun that kept on coming from the best new toy any towheaded lad could ever hope to receive on his thirteenth birthday: an erection. And being a comedian was just the best job in the world for a boy who wanted to play with that toy all the time.

Dick's reputation as a hound was so notorious in the comedy world that on the signature wall of one club's green room, below where Dick had signed his name, someone had added the words fucked this and then punched a small hole in the wall.

Dick did not mind. He remained so permanently pleased at his accomplishment of avoiding work and getting a lot of women that he was not even bothered by the slightly embarrassing predicament of being a thirty-five-year-old young comedian. It may not have been the perfect situation, but, like for Russians who once defended communism because they remembered the czar, it beat the old life -- which for Dick was his twenties, when he had worked as an engineer and hated every minute of it. Dick never tired of explaining why being a comedian had it all over anything else a man might do to make his living.

"If you work in an office, you see the same chicks every day. Okay, four of them are married, one's a dyke, two of them are ugly -- so after you fucked the pretty one, you're done. But us -- say you do five shows a week, average a hundred people a show, half of them are women, that's two hundred and fifty new women you could meet every week."

Of course, Dick's ceaseless philandering did have its downside, such as it sometimes bothered his wife -- but since she'd already divorced him, there wasn't much she could do about it except move out, which she so far hadn't done. This arrangement baffled everybody: a couple divorced for three years yet still living as man and wife with their eleven-year-old son, Joel, in a nice apartment in the Riverdale section of the Bronx. (Dick also maintained a small pied-à-pussy on the East Side of Manhattan.) People who didn't know the couple well surmised that it was a marriage of convenience, devoid of passion, but that was not the case. It was, in fact, a marriage of constant inconvenience, with plenty of passion. Dick loved having sex with Janet, because wooing her out of the constant state of resentment and hatred she felt for him was just a different form of the song and dance he had to perform for strange women to get them into bed. It was the song and dance, more than the sex, that motivated Dick -- and the fact that the one form of it always made the other more exciting was the beauty of his system. Dick often told his cronies how much he loved to come home to his marital bed after a weekend away cruising bimbos -- although even Janet drew the line the time she found a blond hair while removing her husband's underpants. Janet didn't like the arrangement; she wasn't a happy woman. But for some reason, she let Dick have his cake and fuck it, too. She knew he wouldn't change, but she was tragically unable to extricate herself from a man who believed that "finding a blond hair in your underwear is what show business is all about."

Perhaps, then, they stayed together for the child. Janet could not deny that Dick and Joel had a special relationship. Certainly, no son could have asked for a more constant playmate, even if it did come in the person of his father. Dick often took Joel on gigs near home, especially if it was a club where they could play pinball or video games together before he went onstage. Then, after the show, Joel would watch his father try to score in a different way. Dick never betrayed the slightest embarrassment while chatting up a girl closer to his son's age than his own, although on the way home he always told the boy, "Don't tell your mother about this."

As for Joel, he seemed to take it all in stride. He was a bit of a brat, but only because Dick simply had not an iota of will to discipline his boy. Discipline was not a part of their relationship, or of Dick's character or in his vocabulary. To hear Dick and his son talk to each other was a riot, because it sounded more like two young brothers -- arguing over trivial matters, calling each other names, leading each other i

Five comedians sat on a train. They were Dick, Shit, Fat, Chink, and Buick, so pseudonymed for their specialities de fare: Dick, who did dick jokes; Shit, who did shit jokes; Fat, who did fat jokes; Chink, who made fun of the way Oriental people spoke; and Buick, the observationalist, whom everyone called Buck, and so he came to be called Buck.

"Hey, get down off there!" ejaculated the conductor, and the giggling colleagues dismounted and took their rightful places inside the gleaming trispangled Amtrak Minuteman, bound for Trenton, Philadelphia, Wilmington, Baltimore, and Washington, D.C., towns where comedy was king and the audience peasants.

Near the back of the train, the comedians found a suitable enclave where three could face two and sprawled inside it. Fat took up two seats alongside his mentor, Dick, while the Damon and Pythias of comedy, Shit and Buck, sandwiched their protégé, Chink, on the opposing bench. The boys were dressed in the casual attire of the day: sneakers, Sasson jeans, sweatshirts, button-downs, and almost-leather jackets or blue hooded parkas. Except for Buck, who enjoyed the distinction of always dressing in a sports jacket and tie. They could have passed for any other five young white men who were completely out of their minds.

After the train pulled out of Penn Station, Shit got up to use the bathroom and then returned to his seat completely naked. The other boys laughed at the sight of him, although certainly not as hard as they would have laughed if it was the first time they'd seen him do such a thing. It was the first time for the other passengers, however -- but since they were New Yorkers, they probably had seen naked people in public before, probably that day. What they didn't know was that Shit and his friends were not actually dangerous, just comedians -- young comedians at that -- and playing was simply their day job.

Amtrak conductors dreaded groups of young comedians. Sometimes comedians could cohabit for a while in an enclosed area, but more often than not, play-fighting would get out of hand or one of them would attempt to pick something off another's fur and cause a yelp, or drop a rock on his head, and pretty soon the conductor would have to come by and distract them with bananas. This quintet counted itself more mature than most young comics, which is a little like saying absolutely nothing at all.

It was difficult, in fact, even to measure maturity among comedians by any of the usual societal yardsticks; certainly, age was not a factor. Shit and Dick -- who, in fairness, had outgrown their nicknames, earned during those first few panicky months of stand-up, when mention of those subjects was the only way they knew to ensure the steady oxygen of laughter -- were the eldest, at twenty-nine and thirty-five. But Shit, as worldly as he was -- and he was -- just liked to get naked. He was especially fond of walking into the men's room of a nightclub when one of his friends was onstage, then emerging sans attire for a casual stroll back to the bar. Of course, the comic onstage would have to stop Shit to ask if he hadn't forgotten something, at which point Shit would feign embarrassment and hasten back to the loo, only to reemerge with a drink in his hand and a thanks for the reminder. Not that trains and nightclubs were the only places where Shit liked to get naked: bachelor parties, double dates, hotel rooms, Yankee Stadium -- any place where other comedians were around to appreciate it, and the chance for arrest minimal, would do.

The chance for arrest on the train was getting a little stronger as Shit remained nude in his seat, but Dick was in the middle of a story, so Shit's arrest, if it came, would have to wait. Especially since the story was about Shit and Dick and another comedian getting naked the week before at an all-girl Catholic school in upstate New York, where the trio had been hired to perform.

"You didn't tell me about that," Buck whined.

"Do I have to tell you every time it happens?" Shit joshed. Still, Buck was a little hurt.

"So we walk in," Dick continued, "and there's two nuns and another woman -- not a nun but, you know, nunlike -- and they were all real nervous that we were gonna say something improper or do something like, Christ, I don't know, get naked or something."

"Why did they book you in the first place?" Fat asked.

"Who knows, shut up," Dick said quickly, but then smiled at his idolator. "Anyway, they didn't want us anywhere near the girls, so right away they hustle us down into this underground rec room with a lot of pictures of Jesus on the walls and a Ping-Pong table."

"Jesus loved Ping-Pong. He invented that Chinese grip," Buck offered.

"Although for some reason he's better known for other things," Shit added.

"They had Ping-Pong leagues back then -- the National and the Aramaic," Chink topped, with -- to no one's surprise -- the better joke.

"Anyway," Dick tracked, "they put us down there and tell us to stay put until it's time to do the show."

The boys were laughing already, because they knew the punchline.

"I had to." Shit smiled, and everyone nodded sympathetically, as one might for a more normal addiction, like gambling or defecating on glass coffee tables.

"But I didn't have to!" Dick shouted with a big laugh. "Except now I'm the only one with my clothes on, so -- "

"Peer pressure," Buck said.

"Exactly -- I mean, hey, what am I, not gonna get naked? No. So then the two nuns and the other chick come back, and these boneheads are playing Ping-Pong -- "

"Naked?" Fat asked.

"Have you been listening to the story?" Shit asked him.

"Yeah, naked," Dick scolded Fat. "Naked, okay? We were naked, this is a naked story. We're naked. And then the nuns come in -- the nuns were not naked, did I make that clear? -- and they see two guys playing Ping-Pong, and their dicks are flopping around, and I'm standing on a chair over the net like I'm judging!"

Everybody howled at that. Then Fat asked: "Who won?"

More howling. More big passenger-alarming howling, which made the conductor come by, and he was howling mad. But Shit had talked his way out of nakeder spots than this, and he toddled off to the bathroom to get dressed. When he returned, though, Shit was in a decidedly fouler mood than when he'd left, which may have been due to the restrictiveness of clothing or just because he liked descending into fouler moods.

"Mind if I eat while you smoke?" he snarled at Dick and Buck, who had lit up just as Shit removed the foil on his Amtrak-microwaved lunch.

"Easy, pal," said Buck. "God, you're as ornery as..."

"As a man stuck for a metaphor?" Shit countered.

"Boy, you're in a mood," the normally apolitical Chink interposed. "What's eatin' ya?"

"Comedy, boys. Comedy is eating me alive."

With that the others sang out in ridicule of Shit, condemning him for the negative attitude he was now imposing upon their jolly sojourn. They all liked to perpetuate the myth amongst themselves, and especially among civilians, that they were special members of society by virtue of their exemption from all accouterments of the rat race -- i.e., alarm clocks, regular hours, long days, bosses, offices, or the need to concentrate on anything for more than a few seconds. They wore the deadly sin of sloth like a badge of honor, and they relished the chance run-in with childhood friends who'd listen, mouth agape, to the description of a life comprised of recess.

But Shit wasn't buying it today. He bullishly pressed on with a discussion of reality.

"We're being exploited," he said. "They're filling that room every night of the week, getting a five-dollar cover and a two-drink minimum, and we're getting cab fare."

Shit was referring to The Club, the premier Manhattan showcase club on the Upper East Side, where the boys were among forty or so young comedians and comediennes presently getting their acts together. On this particular Friday afternoon, however, they were taking those acts on the road, and on the road -- well, the wages sucked there, too: $250 a weekend for the headliner, $150 for the middle act, $75 for the MC.

But at least now, in 1979, there was a road. Veterans like Dick and Shit, who'd already been at this game for four years, remembered when the only places for a young comic to get onstage were the handful of showcase clubs in New York and L.A. These hot spots, of which The Club was currently the hottest, presented a score of comedians every night, offering them exposure in the country's media capitals and a place to "work out" in exchange for their services, gratis. But as the decade drew to a close, a major new trend in the comedy boom was catching fire: the local comedy club. In cities all across the country, a new vaudeville was slouching to be born. Restaurant basements, hotel lounges, old coffeehouses -- even storefronts -- were being converted into clubs where two or three of these young comedians from New York or L.A. could be brought in each weekend to perform stand-up comedy. It was a trend that fed on itself: Encouraged by the expanding number of young comics available, clubs opened up by the score, and encouraged by all the places to work, hundreds of young men and women began to quit their day jobs.

So what wasn't to like?

To Buck, the recent comedy boom was the ultimate in bad luck. Because he was not part of a trend! He was one of the ones who was born to do it! He would have been a comedian in any era, and curse the luck that he came of age just as every asshole in America who had ever gotten a laugh at a fraternity party was now crowding the field. For decades, to be a comedian had meant you were literally one in a million, as there were certainly no more than two hundred professional comedians in the whole country. But now, just as he was ready to fulfill his lifelong dream, comedians were positively pullulating, breeding like mosquitoes after a wet spring in these stagnant pools they called comedy clubs. Buck laughed every time Johnny Carson brought a new comedian on The Tonight Show with the standard comedy-is-the-hardest-commodity-in-our-business-to-find introduction.

Hardest commodity to find? You could barely swing a dead cat nowadays without hitting some dickhead who called himself a comedian!

And the more comedians there were, the more the bargaining power of each descended.

"How many seats in the Washington club?" Shit continued, still on his high horse, "Three hundred? Same with Philly. And they're collecting five or six at the door, plus drinks, times four shows. You figure it out."

"You're just pissed because you're middling for me," Buck kidded, with a mischievous glint in his eye.

"Blow me," Shit responded, with absolutely no glint.

Shit, Buck, and Dick, you see, were on a mission of mercy this weekend, helping the novice members of the group, Chink and Fat, secure their very first out-of-town gigs, as MCs in Baltimore and Wilmington, respectively. Unlike at The Club, the MC job in an out-of-town club was the least important, consisting mainly of warming up the crowd for fifteen minutes, then introducing the middle act and the headliner, who performed the bulk of the real comedy for the evening. Thus the task of local MC was normally handled by someone local -- even, at times, by a noncomedian, like the owner of the club or a hostess or Gallagher. But Buck and Shit had persuaded the owner of Shennanagins, the Baltimore club, to let Chink get his feet wet on the road in this manner, and in return for this favor, they had agreed to co-headline, thereby ensuring that the show would at least have two veteran acts should Chink prove to be a disaster. Dick, being perhaps the strongest and most in-demand performer currently working in the New York comedy pool, was not asked to make a similar concession -- not that Buck and Shit should have been asked to, either. But if the owner of Shennanagins, Harvey Karrakarrass, had given a comedian something for nothing, he would have faced possible disciplinary action from the Schmucks' Association, to which all club owners belonged.

And, in truth, Buck and Shit were happy to do it: They loved Chink and believed in him. Moreover, they enjoyed doing good, almost as much as they enjoyed the idea that they were doing good. Children of the sixties, Shit and Buck held forth on the train about the new humanity alive at The Club -- how different it was from the bad old days there! Why, in days gone by, the senior acts barely spoke to the rookies, and certainly never gave them a helping hand. But then a revolution of kindness swept over the comic landscape behind its charismatic leader, Shit. Upon gaining his own stature at The Club, Shit reached out to the tyros who came along after him. One of them was Buck, who'd arrived on the scene only a year and a half ago -- not that you'd know it by the way he carried himself. Buck was the kind of guy who could have headlined only twice before in his life and make it sound for all the world as if he was a grizzled veteran. And since he had only headlined twice before, this talent came in handy.

Now, if he only had an act.

An act would have really been helpful a few months earlier, when Buck did his second headlining gig, in Montreal. The owner there wanted an hour from the headliner, and Buck assured him an hour would be no problem. But in truth, an hour was quite a problem, because Buck did not have an hour of material. He did not have a half hour of material, but with a liberal sprinkling of "Where you from?"s with an uncommonly receptive audience, he had been able to clock in close enough to the usual forty-five-minute headliner finish line to pass muster on his first headlining gig, at Shennanagins.

So Buck went to Montreal feeling pretty cocky -- quite a feat for a comedian who was 90 percent attitude and 10 percent act. Of course, a formula like that was right at home in the Big Apple: One colleague had already suggested that Buck bill himself as "the act you're not good enough to see." Buck enjoyed that. He liked having a reputation, even if it was a bad one.

And he didn't want to lose it. So when he got back to New York and everyone asked how things had gone up in Canada, he said they had gone well -- referring, apparently, to timely air service, pleasant hotel accommodations, and delightful sightseeing in the day.

As for the shows, he had suffered only a bit less horribly than the crowds who had had to watch him that weekend -- watch him die four slow, painful deaths. Nothing in his past experience as a comedian -- and almost all of it to that point had been pretty tough -- had prepared him for that. At The Club, yes, the first year had been a nightmare onstage, but every comedian's first year is a nightmare: going on for three drunks at two in the morning, desperately trying to find a distinctive voice, and being rudely awakened to the fact that having been a funny guy all your life is a world apart from being a professional comedian. But at least at The Club you were just one comic in a nightly parade, and the worst beating never lasted more than twenty minutes. But in Montreal, there he was, fifteen minutes into an hour show, and pretty much wad-shot of material.

And no closing bit! The Jordache jeans commercial -- which he "parodied" by sticking his ass out -- did not run in Canada. The biggest laugh Buck got in Montreal that weekend came from his unintentionally mispronouncing the name of the renegade Quebecois prime minister, René Levesque.

Onstage those nights, Buck thought about stealing from his friends -- who would know, it's Canada -- but he had too much pride for that. He even had too much pride to get off at forty-five or fifty or fifty-five, for crying out loud! How much more merciful that would have been for all concerned, not least the audience. Sitting through Buck was like watching an insect that suffers the misfortune of being only half stomped under someone's heel. He writhed and stammered and got hostile atop a little wooden platform in a small basement that had a liquor license while people despised him in two languages.

Buck was not a comedian who bombed gracefully. It was just so hard for him to say nothing when a good joke died. That was all he ever had to do -- say nothing and go on to the next one; the crowd wouldn't even have realized a joke had been told, and they would have still liked him. What could be easier than to just shut up?

Except for one thing: It hurt. To Buck, an unrequited joke was like offering someone a gift and having it thrown back in your face.

That, and one other tiny, little thing: They were wrong! They, sitting there, staring at him as if it were his fault! To say nothing would be acceding to that misconception -- and what kind of weenie takes upon himself the sins of others?

Jesus Christ?

Oh, Him.

At night in the hotel room, Buck cried and thought about something from Greek History 201, some character named Silenus, who told somebody in some play or book or something: "You ask what is best for you? Nothingness. To never have been born. To not be."

Well, hey -- who needs to listen to a gloomy gus like that? Especially since, other than Montreal, things had finally started going well for Buck. Just the fact that he was working out of town proved that he was finally "on the raft": that was the image that kept going through Buck's mind all through that first year at The Club, when he wanted so badly to pull himself out of the intolerable nobody-newcomer sea and get on board with the dozen or so regulars, like Shit and Dick. Their support sustained him in those trying times -- it meant so much to have their respect, to know they thought of him as a contender and not a pretender -- but it still wasn't being one of them. It wasn't being part of the elite cadre, who went on at a decent hour any night they came in and who treated each other like peers and who did real paying gigs around the city, for fifty bucks here, seventy-five there, and sometimes, on weekends out of town, for even more, enough to finally start earning their living from comedy.

From comedy! What a rush that was, to actually be making your living from this! Maybe even to be despised by the waiters at the Blue Spoon diner: that was the ultimate sign of arrival, because the actors who waited tables at the Blue Spoon hated the comedians who ate there -- you could see it in their eyes and by the way they threw the food at them -- because actors had to work a real job until they hit pay dirt, whereas comedians were finaglers who knew how to survive without busing tables for Greeks. The more the actor-waiters hated the comics, the more the comedians loved it. Oh, how wonderful that would be, Buck thought -- to be someone waiters hated and threw food at!

But to move up at The Club was an ordeal even for so ambitious a comer as Buck. There was something of an old-boy network in place, and the dozen or so spots in prime time (after ten and before one, or between the time the crowd warmed up and burned out) went to the same comics every night, the ones who'd been there for three or five or even seven years. At The Club, seniority counted.

Seniority really pissed Buck off. This was show business, he thought -- not the Ford motor plant. How could they keep putting up the same people, the same people who obviously weren't going anywhere or else they'd have been there by now?

Buck had a point about that. Some of the guys on the raft really weren't that talented. Buck wanted to whisper that opinion to Dick or to another supportive colleague, Norma, because they were the reigning MCs at The Club and as such had the power to choose who went on -- but he hesitated. That is, he paused for half a second before saying it.

"He rambles on so much before the punchline," Buck might say with a cringing disdain about some poor act who couldn't hear him because he was busy onstage.

"Yeah," Dick would giggle. "And after."

Damn, you just couldn't denigrate another comedian behind his back enough for it to have any impact. Everybody bitched about everybody, so nobody really listened.

Eventually, though, perseverance paid off for Buck one Friday night. The other off-the-raft comics didn't even come in on the weekends because, unlike the weeknights, the Friday-Saturday lineups were prescheduled, so there wasn't even a chance for a rookie to get on -- unless somebody didn't show up. For months this was what Buck had been hoping for -- that some comic with a scheduled spot would be unable to find a cab or would oversleep or, if it had to be, would get bludgeoned to death on the subway.

When it finally happened (the comedian, thank God, survived the bludgeoning), Buck at long last got his chance in prime time. He was nervous and he was raw and he still had a lot of bad habits. But Buck was right about one thing: He was born to do it, and that night he proved it.

After the show, Buck went home to his shithole studio apartment on West 49th Street and exulted, just sat up all night and exulted. He was on the raft. He'd broken through, and it was a feeling that compared to only two other moments in his life -- the day he came into the Little League championship game as a relief pitcher and saved it for his team before the whole town, and the night during sophomore year in high school after his first successful date, when he walked home in such a stupor that he overshot his own house by half a mile.

Buck smiled and thought about those two moments and now this third one.

Then he stopped exulting: Twenty-four years old, and I can count only three great moments in my life?

Jesus, this show business shit better pay off.

"I see Ted Kennedy's going to announce today."

Shit leaned back against the Amtrak-brown upholstery and spread The New York Times before him.

"Throwing his hat into the river, is he?" Dick asked.

"Illegal spritz," Buck announced, using the term that meant a comic was committing the faux pas of deploying stage material in a social setting.

"Get outta here," Dick answered. "I don't do political stuff."

"Nobody does anymore," Shit lamented.

"I do," Buck protested, perhaps referring to his insightful routine about the choice in the last election being akin to someone asking, "If you had to, what would you rather eat, shit or puke?"

"I mean nobody does it exclusively, like Mort Sahl," Shit explained.

"Who?" Fat wanted to know.

"Kids today," said Shit, shaking his head. "It's gonna be him and Reagan."

Oh, thought Fat: Mort Sahl would be running against Reagan.

"You think Kennedy'll beat Carter for the nomination?" Buck asked Shit.

"Oh yeah. The Democrats can't resist nominating a Kennedy. Will Rogers said, 'I don't belong to an organized party, I'm a Democrat.'"

"I hope he didn't open with it," Dick snickered.

"Why do you hate the Kennedys so much?" Buck asked Shit. "I never understand that -- you're Irish, Catholic, charming, witty, arrogant. You grew up in Boston. Is it just that you think you should have been a Kennedy?"

"They're just horrible people. Snot-nosed rich kids on an ego trip."

Buck bridled: "So? You can't do good for people if you're on an ego trip? Isn't there such a thing as an ego trip for good? A fucking snotty-ass Park Avenue surgeon, okay -- but he's brilliant, his ego trip is saving lives: 'Saved another one today, honey. They didn't think it could be done, but luckily I was around.' I mean, he's a dick, but he saves lives."

"So why does he have to be a dick about it?" Shit objected.

"Why? Who the fuck knows. Maybe because he wouldn't have the confidence to cut open your chest if he wasn't. You take away all the people who do important things because they're dicks, who'd be left to run things?"

"So this is your we-need-the-dicks-to-run-things theory," Shit mocked with a gentle smile.

"Are you familiar with the no-room-at-the-inn syndrome?" Buck shot back.

"No, but I am familiar with the no-room-service-at-the-inn syndrome. That's where you have to go down to the coffee shop for incense and myrrh, which is just as well, because room-service myrrh is usually wildly overpriced," Shit joked.

"No, it means the world does not want a powerful birth. When they know a Jesus is coming into the world, there's never any room at the inn."

"Maybe they were remodeling that week," Dick kidded.

"And you're saying that's why they killed the Kennedys?" Shit asked.

"No, I wasn't, but now that you mention it, that's exactly right. It's always the people that give hope who get shot -- Lincoln, King, the Kennedys."

"McKinley," Fat said, surprising everyone.

"Ah yes, McKinley," Shit said. "Gave every kid in America hope, 'cause they figured if he could grow up to be president, everybody had a shot."

"Ted Kennedy," Chink piped up. "His brother was a hero because he smashed his boat during the war, this guy drives a car into a river. Close, Ted, real close, but it's gotta be a boat. There's gotta be some kinda war goin' on."

"That's so funny," Buck pronounced. "You gotta do that."

"He speaks in material," Shit added.

"Do we have to talk about politics?" Fat asked, pissed that once again Chink had scored with the big boys.

"Everything's politics," Shit said. "Talking about us getting paid what we deserve, that's politics."

"So stop talking about it." Dick laughed.

"You know, the reason we don't get paid at The Club," Buck rejoined, unable to forgo the argument he and Shit had already rehearsed a dozen times, "is because The Club is a place to work out, not to work. It's a trade-off. They use us, and we use them to get our act together. If they paid us real money, we'd be obligated to do our best set every time. We couldn't experiment."

"Oh, come on," Shit returned. "How much experimenting is really going on in there? Everybody's so afraid they'll lose their place at the trough, they do their best set every time anyway."

"I don't," Buck said.

"You don't have a best set," Dick teased.

"No, you need a guitar for that," Buck came back, implying that Dick's use of a musical instrument adulterated the purity of straight monologue.

But Dick was genuinely ungored. Most comics were thin-skinned and easily goreable, but not Dick. He was hard to gore, no matter how many brightly colored sharp sticks one stuck into his back.

"That place is our studio," Buck continued. "Stand-up comedy is an art form. You don't pay the artist to go to class and learn shading and perspective."

"We need a union," Shit stated flatly, and then launched into his speech about how the club owners were scum and how the comedians could break their exploitative lock if only they would band together.

But the comedians did not want to talk politics on this afternoon, so Shit's jeremiad was quickly hushed. Dick especially was bored by the subject because he was -- and would be the first to admit that he was -- still a little boy. Not that this wasn't true of most comedians, but with Dick it was more literal. He was a little boy who continued to enjoy all the pleasures of little boydom -- pinball, video games, comic books, cartoons -- although none of those pleasures came close to supplying the fun that kept on coming from the best new toy any towheaded lad could ever hope to receive on his thirteenth birthday: an erection. And being a comedian was just the best job in the world for a boy who wanted to play with that toy all the time.

Dick's reputation as a hound was so notorious in the comedy world that on the signature wall of one club's green room, below where Dick had signed his name, someone had added the words fucked this and then punched a small hole in the wall.

Dick did not mind. He remained so permanently pleased at his accomplishment of avoiding work and getting a lot of women that he was not even bothered by the slightly embarrassing predicament of being a thirty-five-year-old young comedian. It may not have been the perfect situation, but, like for Russians who once defended communism because they remembered the czar, it beat the old life -- which for Dick was his twenties, when he had worked as an engineer and hated every minute of it. Dick never tired of explaining why being a comedian had it all over anything else a man might do to make his living.

"If you work in an office, you see the same chicks every day. Okay, four of them are married, one's a dyke, two of them are ugly -- so after you fucked the pretty one, you're done. But us -- say you do five shows a week, average a hundred people a show, half of them are women, that's two hundred and fifty new women you could meet every week."

Of course, Dick's ceaseless philandering did have its downside, such as it sometimes bothered his wife -- but since she'd already divorced him, there wasn't much she could do about it except move out, which she so far hadn't done. This arrangement baffled everybody: a couple divorced for three years yet still living as man and wife with their eleven-year-old son, Joel, in a nice apartment in the Riverdale section of the Bronx. (Dick also maintained a small pied-à-pussy on the East Side of Manhattan.) People who didn't know the couple well surmised that it was a marriage of convenience, devoid of passion, but that was not the case. It was, in fact, a marriage of constant inconvenience, with plenty of passion. Dick loved having sex with Janet, because wooing her out of the constant state of resentment and hatred she felt for him was just a different form of the song and dance he had to perform for strange women to get them into bed. It was the song and dance, more than the sex, that motivated Dick -- and the fact that the one form of it always made the other more exciting was the beauty of his system. Dick often told his cronies how much he loved to come home to his marital bed after a weekend away cruising bimbos -- although even Janet drew the line the time she found a blond hair while removing her husband's underpants. Janet didn't like the arrangement; she wasn't a happy woman. But for some reason, she let Dick have his cake and fuck it, too. She knew he wouldn't change, but she was tragically unable to extricate herself from a man who believed that "finding a blond hair in your underwear is what show business is all about."

Perhaps, then, they stayed together for the child. Janet could not deny that Dick and Joel had a special relationship. Certainly, no son could have asked for a more constant playmate, even if it did come in the person of his father. Dick often took Joel on gigs near home, especially if it was a club where they could play pinball or video games together before he went onstage. Then, after the show, Joel would watch his father try to score in a different way. Dick never betrayed the slightest embarrassment while chatting up a girl closer to his son's age than his own, although on the way home he always told the boy, "Don't tell your mother about this."

As for Joel, he seemed to take it all in stride. He was a bit of a brat, but only because Dick simply had not an iota of will to discipline his boy. Discipline was not a part of their relationship, or of Dick's character or in his vocabulary. To hear Dick and his son talk to each other was a riot, because it sounded more like two young brothers -- arguing over trivial matters, calling each other names, leading each other i

Recenzii

"Anyone considering a career in stand-up comedy should read this book, then consider something else, because all this great stuff is over."

-- Jerry Seinfeld

"One of the funniest novels since John Kennedy Toole's A Confederacy of Dunces."

-- Library Journal

"Crisp, funny, bitter and wise....Bill Maher really knows stand-up comedy."

-- Steve Allen

"This is the novel I would have written about stand-up comedy if I was a sick egghead like Bill Maher."

-- Roseanne

-- Jerry Seinfeld

"One of the funniest novels since John Kennedy Toole's A Confederacy of Dunces."

-- Library Journal

"Crisp, funny, bitter and wise....Bill Maher really knows stand-up comedy."

-- Steve Allen

"This is the novel I would have written about stand-up comedy if I was a sick egghead like Bill Maher."

-- Roseanne