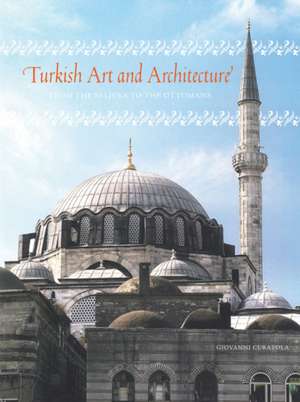

Turkish Art and Architecture: From the Seljuks to the Ottomans

Editat de Giovanni Curatolaen Limba Engleză Hardback – 2 noi 2010

This vibrantly illustrated volume chronicles nearly a millennium of Islamic art and architecture in Turkey.

Illustrated with some 250 attractive and well-chosen color photographs, Turkish Art and Architecture is fascinating reading for anyone with an interest in Turkey, and an essential reference for any student of Islamic art and architecture.

The Anatolian peninsula, one of the oldest seats of civilization, has been ruled by a succession of great powers, including the Romans and their successors in the East, the Byzantines. Its Islamic era began in 1071, when the Seljuk Turks, nomads from Central Asia who had already taken control of Persia, defeated the Byzantine army at Manzikert and moved west, creating a new sultanate in Anatolia. The Seljuks were eventually succeeded in this region by the Ottoman Turks, who crossed the Bosphorus to conquer an exhausted Constantinople in 1453, and went on to extend their power far beyond the borders of modern Turkey, establishing an empire that endured until the early twentieth century.

Ruling over a land that had always been at the crossroads of east and west, these Islamic dynasties developed a cosmopolitan art and architecture. As art historian Giovanni Curatola demonstrates in this insightful new book, they combined elements of the prestigious Persian style and memories of their nomadic past with local Mediterranean traditions, and also adopted local building materials, such as stone and wood. Curatola introduces us first to the new types of buildings introduced by the Seljuks—like the caravansary and the türbe, or mausoleum—and then to the sophisticated architectural achievements of the Ottomans, which culminated in the great domed mosques constructed by the master builder Mimar Sinan (d. 1588). He also traces the history of the decorative arts in Turkey, which included lavishly ornamented carpets, manuscripts, armor, and ceramics.

Illustrated with some 250 attractive and well-chosen color photographs, Turkish Art and Architecture is fascinating reading for anyone with an interest in Turkey, and an essential reference for any student of Islamic art and architecture.

The Anatolian peninsula, one of the oldest seats of civilization, has been ruled by a succession of great powers, including the Romans and their successors in the East, the Byzantines. Its Islamic era began in 1071, when the Seljuk Turks, nomads from Central Asia who had already taken control of Persia, defeated the Byzantine army at Manzikert and moved west, creating a new sultanate in Anatolia. The Seljuks were eventually succeeded in this region by the Ottoman Turks, who crossed the Bosphorus to conquer an exhausted Constantinople in 1453, and went on to extend their power far beyond the borders of modern Turkey, establishing an empire that endured until the early twentieth century.

Ruling over a land that had always been at the crossroads of east and west, these Islamic dynasties developed a cosmopolitan art and architecture. As art historian Giovanni Curatola demonstrates in this insightful new book, they combined elements of the prestigious Persian style and memories of their nomadic past with local Mediterranean traditions, and also adopted local building materials, such as stone and wood. Curatola introduces us first to the new types of buildings introduced by the Seljuks—like the caravansary and the türbe, or mausoleum—and then to the sophisticated architectural achievements of the Ottomans, which culminated in the great domed mosques constructed by the master builder Mimar Sinan (d. 1588). He also traces the history of the decorative arts in Turkey, which included lavishly ornamented carpets, manuscripts, armor, and ceramics.

Preț: 553.10 lei

Preț vechi: 601.19 lei

-8% Nou

Puncte Express: 830

Preț estimativ în valută:

105.84€ • 111.29$ • 87.45£

105.84€ • 111.29$ • 87.45£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 26 martie-09 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780789210821

ISBN-10: 0789210827

Pagini: 280

Dimensiuni: 240 x 325 x 30 mm

Greutate: 2.38 kg

Editura: Abbeville Publishing Group

Colecția Abbeville Press

ISBN-10: 0789210827

Pagini: 280

Dimensiuni: 240 x 325 x 30 mm

Greutate: 2.38 kg

Editura: Abbeville Publishing Group

Colecția Abbeville Press

Cuprins

Table of Contents from Turkish Art and Architecture

Introduction

Chapter 1: Historical Notes

Chapter 2: Seljuk Architecture: Ornate Stone

Chapter 3: Decorative Arts: Between Byzantium and Central Asia

Chapter 4: Transition and Innovation, 14th to 15th Century

Chapter 5: 1453, from Constantinople to Istanbul

Chapter 6: Sinan, the Genius at Work

Chapter 7: A Glorious Empire, Ottoman Decorative Arts

Chapter 8: After Sinan, Life Goes On

Chapter 9: The 19th and 20th Century, A Decline?

Plans of Key Monuments

Bibliography

Index of Names, Places and Monuments

Introduction

Chapter 1: Historical Notes

Chapter 2: Seljuk Architecture: Ornate Stone

Chapter 3: Decorative Arts: Between Byzantium and Central Asia

Chapter 4: Transition and Innovation, 14th to 15th Century

Chapter 5: 1453, from Constantinople to Istanbul

Chapter 6: Sinan, the Genius at Work

Chapter 7: A Glorious Empire, Ottoman Decorative Arts

Chapter 8: After Sinan, Life Goes On

Chapter 9: The 19th and 20th Century, A Decline?

Plans of Key Monuments

Bibliography

Index of Names, Places and Monuments

Recenzii

"Intricately detailed descriptions with 250 striking photographs, with images of some of the most devoutly illuminating Mosque architecture ever seen between book covers." — ArchNewsNow(dot)com

Notă biografică

Giovanni Curatola, a professor of Muslim archaeology and art history at the University of Udine, has curated such exhibitions as Islamic Art in Italy and Shamans and Dervishes of the Steppes. He is also the editor of The Art and Architecture of Mesopotamia and the co-author of The Art and Architecture of Persia, both published by Abbeville Press.

Extras

Excerpt from Turkish Art and Architecture

Introduction

I do not know how common it is for someone to write a book in order to pay a debt, but it can happen, and that is the case here. Not in the sense that the proceeds from this book will settle any accounts, which I think only occurs with fairly prolific novelists, or political and public figures writing their memoirs, but in a broader way. Simply by living in (and often traveling through) places that begin to feel familiar—on all levels—you come across people who, perhaps unwittingly, expand your horizons, offering you new perspectives, stimuli, and chances for reflection. This was my experience. Writing about Turkey is my way to thank this country. The synthesis of knowledge represented in this book is obviously not only mine. Due to my academic background and profession this book’s approach and content are centered around art history (and to some extent archaeology). But in this writing I hope the perfumes and colors of Turkey, my many meetings and encounters, in solitude and company, also appear, converging in a story that began thirty-five years ago and that I hope has yet to end.

Why Turkey? I have thought about this a great deal, and the answer is simple—and true! I am Italian, and as such find Turkish society, that ancient civilization with its incredible stratifications, the nearest to my own. The similarity I have found between these two regions is hard to describe, but I feel deeply that it is not so much pure affinity as maternal twinship—two children born of the same mother, but brought up differently. It is not only a geographical proximity; it is a more structured, innate, and anthropological connection (maybe it has something to do with Etruscan origins, the Etruscans perhaps having also come from the East). There is certainly a wider Mediterranean perspective, although this can seem and often is very vague. It has something, a lot, to do with the food—olive oil, wine, bread, and fruit (the cherries Lucullus brought to Italy from Anatolian Kerasa), flavors I rediscover everywhere and which help me to understand, to interpret, and to feel at home in Turkey.

I am not claiming to provide a comprehensive narrative, from the Hitties (and before) to the present day, as I lack the technical and cultural tools for this. However, in Turkish art history there seems to me to be an extraordinary and never-belied continuity with the past, albeit a confused one. Let’s just say that there is a synecdoche, an aspect capable of illuminating a whole society. The starting point, present and potent, is Islam at the moment of its strongest impact. Although not triumphant right away, it had a firm grip, summarized by a date, 1071, when the Seljuk Turks defeated Byzantium at Manzikert on the shores of Lake Van, the most eastern of the Anatolian lakes. From this starting point I will do on to recount a world that is a fascinating compendium of differing contributions. The importance of the historic past is obvious, but in the Turkish case three primary influences (and inspirations) meet: the Turkish tribes’ roots in the distant steppes of Central Asia (with both Chinese and Indian influences); the Mediterranean topography, a beautiful land surrounded by the sea but also a land of harsh mountain ranges, plateaus, and vast plains (let’s not forget that Turkey borders on Mesopotamia), a world that for simplicity’s sake we will call Byzantine; and lastly, the influence of Islam—not the Islam of today’s Muslim world, obviously, but that vast and in some ways contradictory Islam of the year 1000. These three nuanced components—and they are only the main ones—create a mosaic or, better still, a kaleidoscopic vision of a country.

I have mentioned that I will be looking at the subject from an artistic viewpoint, and architecture inevitably enters into this picture. Its capacity to transform an area and to reflect the image of a civilization earns it a privileged space in these pages. But decorative arts are equally important. And we have an extremely vast field of investigation to cover: wood furniture (Anatolian production of which ranks among the most significant in the world); carpets, also structurally fundamental; and wall tiles—not just famous sixteenth century ones from Iznik, but also those widely used in the thirteenth century. And then there are the miniatures, the textiles, the glass, the metalwork…I cannot focus on all of these arts in detail, but will highlight the reciprocal influences and relations, attempting to represent the complexity of all these phenomena and their respective sources, as well as the fantastic vitality and wealth of an important civilization that is not so very different from our own.

Introduction

I do not know how common it is for someone to write a book in order to pay a debt, but it can happen, and that is the case here. Not in the sense that the proceeds from this book will settle any accounts, which I think only occurs with fairly prolific novelists, or political and public figures writing their memoirs, but in a broader way. Simply by living in (and often traveling through) places that begin to feel familiar—on all levels—you come across people who, perhaps unwittingly, expand your horizons, offering you new perspectives, stimuli, and chances for reflection. This was my experience. Writing about Turkey is my way to thank this country. The synthesis of knowledge represented in this book is obviously not only mine. Due to my academic background and profession this book’s approach and content are centered around art history (and to some extent archaeology). But in this writing I hope the perfumes and colors of Turkey, my many meetings and encounters, in solitude and company, also appear, converging in a story that began thirty-five years ago and that I hope has yet to end.

Why Turkey? I have thought about this a great deal, and the answer is simple—and true! I am Italian, and as such find Turkish society, that ancient civilization with its incredible stratifications, the nearest to my own. The similarity I have found between these two regions is hard to describe, but I feel deeply that it is not so much pure affinity as maternal twinship—two children born of the same mother, but brought up differently. It is not only a geographical proximity; it is a more structured, innate, and anthropological connection (maybe it has something to do with Etruscan origins, the Etruscans perhaps having also come from the East). There is certainly a wider Mediterranean perspective, although this can seem and often is very vague. It has something, a lot, to do with the food—olive oil, wine, bread, and fruit (the cherries Lucullus brought to Italy from Anatolian Kerasa), flavors I rediscover everywhere and which help me to understand, to interpret, and to feel at home in Turkey.

I am not claiming to provide a comprehensive narrative, from the Hitties (and before) to the present day, as I lack the technical and cultural tools for this. However, in Turkish art history there seems to me to be an extraordinary and never-belied continuity with the past, albeit a confused one. Let’s just say that there is a synecdoche, an aspect capable of illuminating a whole society. The starting point, present and potent, is Islam at the moment of its strongest impact. Although not triumphant right away, it had a firm grip, summarized by a date, 1071, when the Seljuk Turks defeated Byzantium at Manzikert on the shores of Lake Van, the most eastern of the Anatolian lakes. From this starting point I will do on to recount a world that is a fascinating compendium of differing contributions. The importance of the historic past is obvious, but in the Turkish case three primary influences (and inspirations) meet: the Turkish tribes’ roots in the distant steppes of Central Asia (with both Chinese and Indian influences); the Mediterranean topography, a beautiful land surrounded by the sea but also a land of harsh mountain ranges, plateaus, and vast plains (let’s not forget that Turkey borders on Mesopotamia), a world that for simplicity’s sake we will call Byzantine; and lastly, the influence of Islam—not the Islam of today’s Muslim world, obviously, but that vast and in some ways contradictory Islam of the year 1000. These three nuanced components—and they are only the main ones—create a mosaic or, better still, a kaleidoscopic vision of a country.

I have mentioned that I will be looking at the subject from an artistic viewpoint, and architecture inevitably enters into this picture. Its capacity to transform an area and to reflect the image of a civilization earns it a privileged space in these pages. But decorative arts are equally important. And we have an extremely vast field of investigation to cover: wood furniture (Anatolian production of which ranks among the most significant in the world); carpets, also structurally fundamental; and wall tiles—not just famous sixteenth century ones from Iznik, but also those widely used in the thirteenth century. And then there are the miniatures, the textiles, the glass, the metalwork…I cannot focus on all of these arts in detail, but will highlight the reciprocal influences and relations, attempting to represent the complexity of all these phenomena and their respective sources, as well as the fantastic vitality and wealth of an important civilization that is not so very different from our own.