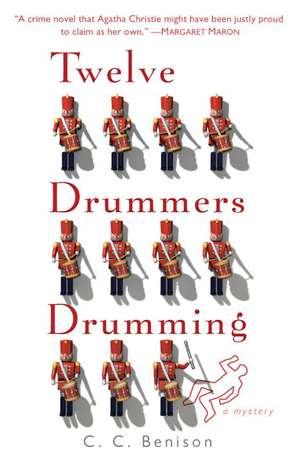

Twelve Drummers Drumming: A Father Christmas Mystery: Father Christmas, cartea 1

Autor C. C. Benisonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 29 oct 2012

Preț: 129.37 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 194

Preț estimativ în valută:

24.76€ • 26.91$ • 20.81£

24.76€ • 26.91$ • 20.81£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 31 martie-14 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780440246466

ISBN-10: 0440246466

Pagini: 400

Dimensiuni: 133 x 204 x 22 mm

Greutate: 0.29 kg

Editura: Bantam

Seria Father Christmas

ISBN-10: 0440246466

Pagini: 400

Dimensiuni: 133 x 204 x 22 mm

Greutate: 0.29 kg

Editura: Bantam

Seria Father Christmas

Notă biografică

C. C. Benison has worked as a writer and editor for newspapers and magazines, as a book editor, and as a contributor to nonfiction books. A graduate of the University of Manitoba and Carleton University, he is the author of four previous novels, including Death at Buckingham Palace. He lives in Winnipeg.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

chapter one

“Thinking of stealing that book, Father?”

The voice at his shoulder startled Tom Christmas. He looked down to see Fred Pike, the village’s elfin handyman, smiling at him with a kind of manic glee.

“What?”

“Stealing that book?”

Tom blinked at Fred, then snatched his hand from the book. Steal This Book was the title. Someone named Abbie Hoffman was apparently the writer. The cover said as much.

“Despite the title’s invitation, I don’t think so,” Tom said, running his finger between his neck and his dog collar. He put the book down next to a copy of The Anarchist Cookbook, which was being offered for thirty pence. In the middle distance, between two rows of stalls, a hefty lad he recognised as Colm Parry’s son Declan, all got up like a Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle, was struggling to push a large drum on a trolley across the lawn towards the stage. Another lad, similarly dressed, was pulling at the other end.

“Thou shalt not steal,” warned Fred.

“Yes.” Tom nodded agreeably. “I’ve heard that.”

Grinning, Fred passed on towards the display of cider-making machinery, near the stage where the two boys were still struggling with the drum. Tom scratched his head, then turned to look at the other titles, all of them political in nature. He picked up a small volume with a red plastic slipcover. Quotations from Mao Tse-Tung. Well-thumbed, it opened at a page that proclaimed, “Political power comes from the barrel of a gun.” Gently, Tom replaced the book. The other bookstalls were a sea of used Jeffrey Archer and Barbara Cartland, but this was a stall of another colour. He thought he knew whose books these once were. But who in a village nestled in the South Devon hills could be enticed to buy them? Even at prices many pence shy of a pound?

“This is quite the collection,” he said to Belinda Swan, the publican’s wife, who was minding the stall. She reminded him of the Willendorf Venus, fleshy and voluptuous in a way that would have stirred a skinny hunter-gatherer, only attired in the modern way: sealed in stretch trousers and miraculously buttressed beneath a deeply scooped blouse.

“Not very Christian, are they?” she responded, picking up Confessions of a Revolutionary and regarding it askance. “We did wonder, but as it’s for the church, we thought you wouldn’t mind, Father.”

“I wish you wouldn’t—”

“Vicar, I mean.”

“Tom is fine.”

“Right. Tom it is. I’ll remember this time. But with your family name, you know, sometimes we can’t—”

“Help it,” he said, finishing her thought. It was a bane of his existence. Once, as a teenager, he’d gone to a fancy-dress party kitted out as Father Christmas, all white cotton-candy beard and hair and itchy red wool, and the honorific—or gibe—clung to him ever after. At the vicar factory at Cambridge he was Father Christmas. As curate in south London he was Father Christmas. In his ministry in Bristol he was Father Christmas. This though he wasn’t High Church. The mercy was his late wife hadn’t been named Mary. His adoptive mother had been, but she had wisely retained her maiden name.

Belinda picked up the Quotations. “I think Ned was the last person in the world who still cared what whatsisnamehere, Mao Tse-tung, thought about anything.”

“What about a billion Chinese?”

“Oh, do you think? I thought the Chinese had rather gone off all this rigmarole.” She opened the book at random and read aloud: “‘We must always use our brains and think everything over carefully.’” Her well-plucked eyebrows went up a notch. “Hard to argue with that. Maybe I should have my kids read this instead of Harry Potter.”

“I take it these books are all Ned’s.”

“Yes, his daughter said to take the lot. ‘Take them, I don’t want to look at them,’ she said. ‘You can burn them,” she said. Well, book burning didn’t seem very nice, so—”

“I’ll buy that one then.” Tom reached into his pocket and pulled out a pound coin.

“Are you sure?”

“To remember Ned, then.”

“But you never met him.”

“Not in the corruptible flesh, no.”

“Of course,” Belinda said, taking the coin and counting out seventy-five pence change. “That’s how you came to us, isn’t it? In a roundabout way. Fancy old Red Ned having a Christian burial. I expect he’s still spinning.”

By chance—or perhaps by design, though arguing the latter was a bit teleological—Tom and his daughter Miranda had been visiting Thornford Regis the week of Ned Skynner’s funeral, staying with his wife’s sister Julia and her husband Alastair. A music teacher at a Hamlyn Ferrers Grammar School outside Paignton, Julia filled in occasionally as organist at St. Nicholas Church and had been called upon to do so for Ned’s funeral that day in early April just over a year ago. Julia had looked at him askance when he’d volunteered to accompany her to the ceremony.

“The expression ‘busman’s holiday’ comes to mind,” she’d said with a smile, though her eyes telegraphed a deeper concern for him, unnecessarily attending a morbid rite for a complete stranger, five months after his wife’s homicide. But Tom was just as happy not to be left with his brother-in-law Alastair, whose disapproval seemed to fall on him like fine rain whenever circumstance threw the two of them together. Besides, funerals, intermittent or in clusters, were part measure of a priest’s life; his professionalism demanded he suspend his own grief to ease the grief of others, and he had done so: Twelve days after Lisbeth’s funeral at the synagogue in St. John’s Wood Road in London, he had taken a funeral at St. Dunstan’s, for a child, no less, and had managed—somehow, just barely—to keep his own heart from breaking.

And, if he had been looking for another reason to accompany Julia, a more frivolous one, he had it: He had not seen the interior of St. Nicholas Church, the grey weather-beaten Norman tower he had glimpsed the day before as he’d driven down into the village. There had been only one impediment. He couldn’t very well take his nine-year-old daughter, to—of all things—a funeral, not so soon after her mother’s death. But Alastair, who had taken the day off from his medical duties, volunteered to abandon plans for his own round of golf and take Miranda to Abbey Park in Torquay to play crazy golf. Tom hadn’t been sure if Alastair wanted to avoid his company or Julia’s. Good manners prevailed before guests, but no central heating could thaw the icy atmosphere between husband and wife that week.

What he would never have known is that he would wind up taking the funeral. The incumbent vicar, the Reverend Peter Kinsey, who had had the living for a mere eighteen months, had failed to appear. Everything else had been at the ready. Ned, at his daughter’s insistence, had been delivered to the lych-gate in a less-than-proletarian mahogany box with brass handles. Julia was at the organ gently working her way through “Ave Verum,” “Love Divine, All Loves Excelling,” and “Morning Has Broken.” There was a lovely display of lilies, forsythia, and iris, with daffodils in separate vases. And there was a decent turnout, Tom later learned, not least because many of the old villagers were amused to see Ned, who had spent four decades declaring religion to be the opiate of the masses from his seat in the pub, getting a send-off from one of the opiate manufacturer’s franchise operations.

Impatience had turned to puzzlement, then to consternation when, after about twenty minutes, the vicar didn’t appear. A call round to the vicarage produced no vicar; nor did it produce the vicar’s housekeeper, Madrun Prowse, who had gone to visit her deaf mother in Cornwall. The Reverend Mr. Kinsey wasn’t at the pub, where the wake was to take place, nor was he at any of the other public places in the village. His mobile was switched off, too. One or two villagers thought someone might have called one or two female parishioners on the off chance, but they kept that to themselves out of respect for Ned’s big send-off. Finally, someone realised that Kinsey’s Audi was missing. It was a Tuesday. Vicar’s day off was Monday. Perhaps he’d gone away for the day and got waylaid somewhere.

Though he might have phoned, someone groused.

It was a chilly April afternoon and the temperamental heating system in the church—adequate, Tom was to later learn, for a fifty-minute Sunday service—was less so for a congregation that had been waiting ninety minutes for the show to begin. The verger might have taken the service, but he was down with flu. The funeral director was able, but Karla Skynner, Ned’s daughter and a churchwarden, determined to sanitise her father’s history in a blaze of Christian piety and learning there was a vicar in the house, beseeched—well, it was more “commanded”—Tom to step in. To Julia’s horror he did—though dressed in corduroy trousers and a battered Barbour, he didn’t feel he would quite fill the contours of the role. Never mind. The vestments were hanging in the vestry, including a purple chasuble. He acquitted himself well enough. He mounted the pulpit and intoned the familiar words: I am the resurrection and the life. As he did so, in this little country church, with its freshly lime-washed walls, its slightly crooked aisle, and its aromas of wood polish, old books, and gently disintegrating woolen kneelers, he felt unaccountably at peace, in a way he had not since that awful autumn day when he had found Lisbeth lying in a pool of blood in the south porch of St. Dunstan’s. It was as though he had come home. As he looked past the faces of the mourners in the front pews to the shifts of light streaming through the Victorian stained glass, he found himself almost brimming with gratitude for the unexpected gift of this moment.

The Reverend Peter Kinsey never did show. In fact, the vicar seemed to have vanished from the face of the earth. Consternation had turned to outright worry three days later when Jago Prowse pointed out that the vicar couldn’t have left the village in his car, because he, Jago, was servicing the very car at Thorn Cross Garage and was having trouble with a very tricky fuel injection system. After that it was police, press, and endless speculation. As the village attempted to recover from this unsettling situation, retired clergy were called upon to fill in for Sunday services. The archdeacon helped, too, as did the rural dean. Even the bishop came down from Exeter to preach a wise sermon. But after two months of intermittent police investigation, Peter Kinsey’s reappearance was declared unlikely. There was, officially, a vacancy in the parish.

But a week’s rest, contemplation, and solitary walks in Devon had helped soften the metaphysical rage that had scorched Tom’s soul in the wake of Lisbeth’s death and decided him for change. He needed a safe place for his daughter, and he needed a rest from the turmoil of inner-city team ministry. As soon as he’d returned with Miranda to Bristol, he sent his CV to the bishop of Exeter, asking to be considered for any vacancy. There was a vacancy, as it turned out—in Thornford Regis—and, in due course Tom was appointed to the living of Thornford Regis. In the magisterial terms of the Church of England, the interview and inspection process was extraordinarily speedy. But a traumatised flock needed a new shepherd. Tom packed up Miranda’s and his things, bade sad farewell to his colleagues at St. Dunstan’s, and made the journey to Thornford Regis for the buttercup-strewn life in a West Country village described by the Times travel supplement as “sleepy” and by the AA Guide to Country Towns and Villages of England as “really a very pretty place.”

From the Hardcover edition.

“Thinking of stealing that book, Father?”

The voice at his shoulder startled Tom Christmas. He looked down to see Fred Pike, the village’s elfin handyman, smiling at him with a kind of manic glee.

“What?”

“Stealing that book?”

Tom blinked at Fred, then snatched his hand from the book. Steal This Book was the title. Someone named Abbie Hoffman was apparently the writer. The cover said as much.

“Despite the title’s invitation, I don’t think so,” Tom said, running his finger between his neck and his dog collar. He put the book down next to a copy of The Anarchist Cookbook, which was being offered for thirty pence. In the middle distance, between two rows of stalls, a hefty lad he recognised as Colm Parry’s son Declan, all got up like a Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle, was struggling to push a large drum on a trolley across the lawn towards the stage. Another lad, similarly dressed, was pulling at the other end.

“Thou shalt not steal,” warned Fred.

“Yes.” Tom nodded agreeably. “I’ve heard that.”

Grinning, Fred passed on towards the display of cider-making machinery, near the stage where the two boys were still struggling with the drum. Tom scratched his head, then turned to look at the other titles, all of them political in nature. He picked up a small volume with a red plastic slipcover. Quotations from Mao Tse-Tung. Well-thumbed, it opened at a page that proclaimed, “Political power comes from the barrel of a gun.” Gently, Tom replaced the book. The other bookstalls were a sea of used Jeffrey Archer and Barbara Cartland, but this was a stall of another colour. He thought he knew whose books these once were. But who in a village nestled in the South Devon hills could be enticed to buy them? Even at prices many pence shy of a pound?

“This is quite the collection,” he said to Belinda Swan, the publican’s wife, who was minding the stall. She reminded him of the Willendorf Venus, fleshy and voluptuous in a way that would have stirred a skinny hunter-gatherer, only attired in the modern way: sealed in stretch trousers and miraculously buttressed beneath a deeply scooped blouse.

“Not very Christian, are they?” she responded, picking up Confessions of a Revolutionary and regarding it askance. “We did wonder, but as it’s for the church, we thought you wouldn’t mind, Father.”

“I wish you wouldn’t—”

“Vicar, I mean.”

“Tom is fine.”

“Right. Tom it is. I’ll remember this time. But with your family name, you know, sometimes we can’t—”

“Help it,” he said, finishing her thought. It was a bane of his existence. Once, as a teenager, he’d gone to a fancy-dress party kitted out as Father Christmas, all white cotton-candy beard and hair and itchy red wool, and the honorific—or gibe—clung to him ever after. At the vicar factory at Cambridge he was Father Christmas. As curate in south London he was Father Christmas. In his ministry in Bristol he was Father Christmas. This though he wasn’t High Church. The mercy was his late wife hadn’t been named Mary. His adoptive mother had been, but she had wisely retained her maiden name.

Belinda picked up the Quotations. “I think Ned was the last person in the world who still cared what whatsisnamehere, Mao Tse-tung, thought about anything.”

“What about a billion Chinese?”

“Oh, do you think? I thought the Chinese had rather gone off all this rigmarole.” She opened the book at random and read aloud: “‘We must always use our brains and think everything over carefully.’” Her well-plucked eyebrows went up a notch. “Hard to argue with that. Maybe I should have my kids read this instead of Harry Potter.”

“I take it these books are all Ned’s.”

“Yes, his daughter said to take the lot. ‘Take them, I don’t want to look at them,’ she said. ‘You can burn them,” she said. Well, book burning didn’t seem very nice, so—”

“I’ll buy that one then.” Tom reached into his pocket and pulled out a pound coin.

“Are you sure?”

“To remember Ned, then.”

“But you never met him.”

“Not in the corruptible flesh, no.”

“Of course,” Belinda said, taking the coin and counting out seventy-five pence change. “That’s how you came to us, isn’t it? In a roundabout way. Fancy old Red Ned having a Christian burial. I expect he’s still spinning.”

By chance—or perhaps by design, though arguing the latter was a bit teleological—Tom and his daughter Miranda had been visiting Thornford Regis the week of Ned Skynner’s funeral, staying with his wife’s sister Julia and her husband Alastair. A music teacher at a Hamlyn Ferrers Grammar School outside Paignton, Julia filled in occasionally as organist at St. Nicholas Church and had been called upon to do so for Ned’s funeral that day in early April just over a year ago. Julia had looked at him askance when he’d volunteered to accompany her to the ceremony.

“The expression ‘busman’s holiday’ comes to mind,” she’d said with a smile, though her eyes telegraphed a deeper concern for him, unnecessarily attending a morbid rite for a complete stranger, five months after his wife’s homicide. But Tom was just as happy not to be left with his brother-in-law Alastair, whose disapproval seemed to fall on him like fine rain whenever circumstance threw the two of them together. Besides, funerals, intermittent or in clusters, were part measure of a priest’s life; his professionalism demanded he suspend his own grief to ease the grief of others, and he had done so: Twelve days after Lisbeth’s funeral at the synagogue in St. John’s Wood Road in London, he had taken a funeral at St. Dunstan’s, for a child, no less, and had managed—somehow, just barely—to keep his own heart from breaking.

And, if he had been looking for another reason to accompany Julia, a more frivolous one, he had it: He had not seen the interior of St. Nicholas Church, the grey weather-beaten Norman tower he had glimpsed the day before as he’d driven down into the village. There had been only one impediment. He couldn’t very well take his nine-year-old daughter, to—of all things—a funeral, not so soon after her mother’s death. But Alastair, who had taken the day off from his medical duties, volunteered to abandon plans for his own round of golf and take Miranda to Abbey Park in Torquay to play crazy golf. Tom hadn’t been sure if Alastair wanted to avoid his company or Julia’s. Good manners prevailed before guests, but no central heating could thaw the icy atmosphere between husband and wife that week.

What he would never have known is that he would wind up taking the funeral. The incumbent vicar, the Reverend Peter Kinsey, who had had the living for a mere eighteen months, had failed to appear. Everything else had been at the ready. Ned, at his daughter’s insistence, had been delivered to the lych-gate in a less-than-proletarian mahogany box with brass handles. Julia was at the organ gently working her way through “Ave Verum,” “Love Divine, All Loves Excelling,” and “Morning Has Broken.” There was a lovely display of lilies, forsythia, and iris, with daffodils in separate vases. And there was a decent turnout, Tom later learned, not least because many of the old villagers were amused to see Ned, who had spent four decades declaring religion to be the opiate of the masses from his seat in the pub, getting a send-off from one of the opiate manufacturer’s franchise operations.

Impatience had turned to puzzlement, then to consternation when, after about twenty minutes, the vicar didn’t appear. A call round to the vicarage produced no vicar; nor did it produce the vicar’s housekeeper, Madrun Prowse, who had gone to visit her deaf mother in Cornwall. The Reverend Mr. Kinsey wasn’t at the pub, where the wake was to take place, nor was he at any of the other public places in the village. His mobile was switched off, too. One or two villagers thought someone might have called one or two female parishioners on the off chance, but they kept that to themselves out of respect for Ned’s big send-off. Finally, someone realised that Kinsey’s Audi was missing. It was a Tuesday. Vicar’s day off was Monday. Perhaps he’d gone away for the day and got waylaid somewhere.

Though he might have phoned, someone groused.

It was a chilly April afternoon and the temperamental heating system in the church—adequate, Tom was to later learn, for a fifty-minute Sunday service—was less so for a congregation that had been waiting ninety minutes for the show to begin. The verger might have taken the service, but he was down with flu. The funeral director was able, but Karla Skynner, Ned’s daughter and a churchwarden, determined to sanitise her father’s history in a blaze of Christian piety and learning there was a vicar in the house, beseeched—well, it was more “commanded”—Tom to step in. To Julia’s horror he did—though dressed in corduroy trousers and a battered Barbour, he didn’t feel he would quite fill the contours of the role. Never mind. The vestments were hanging in the vestry, including a purple chasuble. He acquitted himself well enough. He mounted the pulpit and intoned the familiar words: I am the resurrection and the life. As he did so, in this little country church, with its freshly lime-washed walls, its slightly crooked aisle, and its aromas of wood polish, old books, and gently disintegrating woolen kneelers, he felt unaccountably at peace, in a way he had not since that awful autumn day when he had found Lisbeth lying in a pool of blood in the south porch of St. Dunstan’s. It was as though he had come home. As he looked past the faces of the mourners in the front pews to the shifts of light streaming through the Victorian stained glass, he found himself almost brimming with gratitude for the unexpected gift of this moment.

The Reverend Peter Kinsey never did show. In fact, the vicar seemed to have vanished from the face of the earth. Consternation had turned to outright worry three days later when Jago Prowse pointed out that the vicar couldn’t have left the village in his car, because he, Jago, was servicing the very car at Thorn Cross Garage and was having trouble with a very tricky fuel injection system. After that it was police, press, and endless speculation. As the village attempted to recover from this unsettling situation, retired clergy were called upon to fill in for Sunday services. The archdeacon helped, too, as did the rural dean. Even the bishop came down from Exeter to preach a wise sermon. But after two months of intermittent police investigation, Peter Kinsey’s reappearance was declared unlikely. There was, officially, a vacancy in the parish.

But a week’s rest, contemplation, and solitary walks in Devon had helped soften the metaphysical rage that had scorched Tom’s soul in the wake of Lisbeth’s death and decided him for change. He needed a safe place for his daughter, and he needed a rest from the turmoil of inner-city team ministry. As soon as he’d returned with Miranda to Bristol, he sent his CV to the bishop of Exeter, asking to be considered for any vacancy. There was a vacancy, as it turned out—in Thornford Regis—and, in due course Tom was appointed to the living of Thornford Regis. In the magisterial terms of the Church of England, the interview and inspection process was extraordinarily speedy. But a traumatised flock needed a new shepherd. Tom packed up Miranda’s and his things, bade sad farewell to his colleagues at St. Dunstan’s, and made the journey to Thornford Regis for the buttercup-strewn life in a West Country village described by the Times travel supplement as “sleepy” and by the AA Guide to Country Towns and Villages of England as “really a very pretty place.”

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Splendid . . . An intelligent and empathic protagonist and skillful prose make this a winner.”—Publishers Weekly (starred review)

“[C. C.] Benison does an admirable job balancing humor with suspense. . . . Father Christmas’s first case leaves you eager for his next.”—The Wall Street Journal

“A crime novel that Agatha Christie might have been justly proud to claim as her own.”—Margaret Maron, New York Times bestselling author of Christmas Mourning

“Highly recommended . . . a marvelous series debut.”—Library Journal

“The perfect treat for suspense fans in a holiday mood.”—BookPage

“[C. C.] Benison does an admirable job balancing humor with suspense. . . . Father Christmas’s first case leaves you eager for his next.”—The Wall Street Journal

“A crime novel that Agatha Christie might have been justly proud to claim as her own.”—Margaret Maron, New York Times bestselling author of Christmas Mourning

“Highly recommended . . . a marvelous series debut.”—Library Journal

“The perfect treat for suspense fans in a holiday mood.”—BookPage