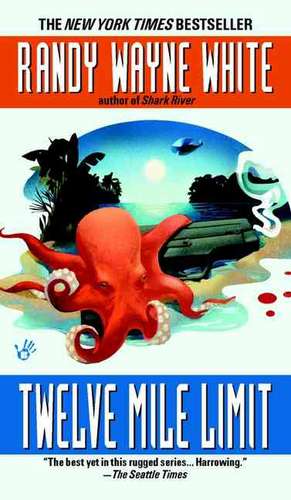

Twelve Mile Limit: Doc Ford, cartea 9

Autor Randy Wayne Whiteen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mai 2003 – vârsta de la 18 ani

It starts out as a fun excursion for four divers off the Florida coast. Two days later only one is found alive-naked atop a light tower in the Gulf of Mexico. What happened during those 48 hours? Doc Ford thinks he's prepared for the truth. He isn't.

Preț: 51.92 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 78

Preț estimativ în valută:

9.94€ • 10.35$ • 8.40£

9.94€ • 10.35$ • 8.40£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 14-28 februarie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780425190739

ISBN-10: 0425190730

Pagini: 368

Dimensiuni: 112 x 177 x 26 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: G.P. Putnam's Sons

Seria Doc Ford

ISBN-10: 0425190730

Pagini: 368

Dimensiuni: 112 x 177 x 26 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: G.P. Putnam's Sons

Seria Doc Ford

Recenzii

"The best Yet in this rugged series." -Seattle Times

"A rip-roaring novel...a colossal leap for this series."-Fort Lauderdale Sun-Sentinel

"A rip-roaring novel...a colossal leap for this series."-Fort Lauderdale Sun-Sentinel

Notă biografică

Randy Wayne White is the author of seventeen previous Doc Ford novels and four collections of nonfiction. He lives in an old house built on an Indian mound in Pineland, Florida.

Extras

Twelve Mile Limit Randy Wayne White

Copyright ã 2002 by Randy Wayne White

Part One

Prologue

On Sunday, November 4, a Coast Guard helicopter was operating fifty-two nautical miles off Marco Island on the west coast of Florida, when a crewman spotted a naked woman on the highest platform of a 160-foot navigational tower.

In the crew chief’s report, the woman was described as a “very healthy and fit” redhead. The woman was waving what turned out to be a wet suit. She was trying to attract the helicopter crew’s attention.

The helicopter, a Jayhawk H-60, was in the area searching for a twenty-five-foot pleasure boat that had been reported overdue nearly two days earlier. According to the report, the motor vessel, Seminole Wind, had left Marco on Friday morning with a party of one man, three women. According to relatives, the foursome had planned to spend the day offshore, fishing and SCUBA diving, but did not return Friday afternoon as expected. The Coast Guard had been searching for the Seminole Wind since Friday night. The crew of the Jayhawk was looking for a disabled boat, not a naked woman waving a wet suit from a light tower.

The helicopter flew east past the tower, banked south, then hovered beside the platform. One of the crew signaled the woman with a thumbs-up. It was a question. The woman signaled a thumbs-up in return—she was okay. Then the woman wiggled into her wet suit, climbed down to a lower platform, and dived into the water. The crew of the Jayhawk dropped a basket seat and winched her aboard.

It was 9:54 a.m.

The woman they rescued was thirty-six-year-old Amelia Gardner of St. Petersburg, a passenger on the vessel that had been reported overdue, the Seminole Wind.

According to the Coast Guard report, the woman was given a mug of coffee from a Thermos and asked what happened. She replied that she’d been a guest on a boat that sank. When the crew chief asked where the boat had sunk, Gardner replied, “Oh dear, God! You mean you haven’t found them?”

She was referring to the two women and one man who’d been aboard with her: the boat’s owner, Michael Sanford, age thirty-five, of Siesta Key; Grace Walker, twenty-nine, a Sarasota realtor; and Janet Mueller, thirty-three, who lived on a houseboat at Jensen’s Marina on Captiva Island and worked part-time for Sanibel Biological Supply, a business owned by a man named Marion Ford.

A Coast Guard crewman shook his head and told the distraught woman, “Nope. We’ve had crews searching for thirty-six hours straight and no one’s seen a thing.”

Gardner told the crew that Sanford’s boat had swamped and capsized at around 3 p.m. Friday while anchored over the Baja California, a wreck they’d been diving. She said the four of them had held on to the anchor line until the boat finally sank at around 7 p.m. and they were set adrift. By then, it was dark, waves had gotten bigger, the wind stronger, and she was gradually swept away from the others in rough seas. Because she had no other options, Gardner began swimming toward the light tower, which she’d been told was approximately four miles away.

“I never thought I was going to make it,” she told the crew chief. “I was sure I was going to die.”

She said that it was a little after 11 p.m., according to her dive watch, when she finally reached the tower, climbed up the service ladder, and collapsed, exhausted, on the lower platform. She’d been on the tower since 11 p.m. Friday—thirty-five hours—and she told them she was very thirsty. She was sunburned, she had barnacle cuts on her hands and legs, and she appeared to be suffering from exposure.

When Gardner was offered the option of being flown to a hospital or remaining on station, she replied that she wanted the helicopter to continue searching. She told crewmen that all three of her companions were wearing wet suits and inflated BCD vests, buoyancy compensator devices. “We’ll find them, we’ve got to find them,” she said, and offered to help the crew get Loran—an electronic navigational system that aids mariners in determining positions at sea—coordinates for the California wreck from her former dive instructor, who lived aboard a trawler at Burnt Store Marina near Punta Gorda.

The crew chief told Gardner that they already had the coordinates for the wreck.

The helicopter crew, with Gardner aboard, searched for two more hours but found nothing—nor did what, by now, was an even bigger search group that included a second H-60 helicopter, a C-130 fixed wing aircraft, the Coast Guard’s eighty-two-foot cutter Point Swift, and a forty-one-foot utility cruiser. The U.S. Coast Guard Auxiliary and other volunteers were also providing boats and crew, but the smaller vessels could not search offshore because the wind was now blowing twenty knots out of the east-northeast.

Hopes of recovering the three missing divers remained high, however. They were all young, all in good shape, and they were all wearing wet suits and inflated vests.

As one of the Coast Guard staff assured Gardner, “Don’t worry, we’re the very best in the world at finding people lost at sea.”

Which is true.

Copyright ã 2002 by Randy Wayne White

Part One

Prologue

On Sunday, November 4, a Coast Guard helicopter was operating fifty-two nautical miles off Marco Island on the west coast of Florida, when a crewman spotted a naked woman on the highest platform of a 160-foot navigational tower.

In the crew chief’s report, the woman was described as a “very healthy and fit” redhead. The woman was waving what turned out to be a wet suit. She was trying to attract the helicopter crew’s attention.

The helicopter, a Jayhawk H-60, was in the area searching for a twenty-five-foot pleasure boat that had been reported overdue nearly two days earlier. According to the report, the motor vessel, Seminole Wind, had left Marco on Friday morning with a party of one man, three women. According to relatives, the foursome had planned to spend the day offshore, fishing and SCUBA diving, but did not return Friday afternoon as expected. The Coast Guard had been searching for the Seminole Wind since Friday night. The crew of the Jayhawk was looking for a disabled boat, not a naked woman waving a wet suit from a light tower.

The helicopter flew east past the tower, banked south, then hovered beside the platform. One of the crew signaled the woman with a thumbs-up. It was a question. The woman signaled a thumbs-up in return—she was okay. Then the woman wiggled into her wet suit, climbed down to a lower platform, and dived into the water. The crew of the Jayhawk dropped a basket seat and winched her aboard.

It was 9:54 a.m.

The woman they rescued was thirty-six-year-old Amelia Gardner of St. Petersburg, a passenger on the vessel that had been reported overdue, the Seminole Wind.

According to the Coast Guard report, the woman was given a mug of coffee from a Thermos and asked what happened. She replied that she’d been a guest on a boat that sank. When the crew chief asked where the boat had sunk, Gardner replied, “Oh dear, God! You mean you haven’t found them?”

She was referring to the two women and one man who’d been aboard with her: the boat’s owner, Michael Sanford, age thirty-five, of Siesta Key; Grace Walker, twenty-nine, a Sarasota realtor; and Janet Mueller, thirty-three, who lived on a houseboat at Jensen’s Marina on Captiva Island and worked part-time for Sanibel Biological Supply, a business owned by a man named Marion Ford.

A Coast Guard crewman shook his head and told the distraught woman, “Nope. We’ve had crews searching for thirty-six hours straight and no one’s seen a thing.”

Gardner told the crew that Sanford’s boat had swamped and capsized at around 3 p.m. Friday while anchored over the Baja California, a wreck they’d been diving. She said the four of them had held on to the anchor line until the boat finally sank at around 7 p.m. and they were set adrift. By then, it was dark, waves had gotten bigger, the wind stronger, and she was gradually swept away from the others in rough seas. Because she had no other options, Gardner began swimming toward the light tower, which she’d been told was approximately four miles away.

“I never thought I was going to make it,” she told the crew chief. “I was sure I was going to die.”

She said that it was a little after 11 p.m., according to her dive watch, when she finally reached the tower, climbed up the service ladder, and collapsed, exhausted, on the lower platform. She’d been on the tower since 11 p.m. Friday—thirty-five hours—and she told them she was very thirsty. She was sunburned, she had barnacle cuts on her hands and legs, and she appeared to be suffering from exposure.

When Gardner was offered the option of being flown to a hospital or remaining on station, she replied that she wanted the helicopter to continue searching. She told crewmen that all three of her companions were wearing wet suits and inflated BCD vests, buoyancy compensator devices. “We’ll find them, we’ve got to find them,” she said, and offered to help the crew get Loran—an electronic navigational system that aids mariners in determining positions at sea—coordinates for the California wreck from her former dive instructor, who lived aboard a trawler at Burnt Store Marina near Punta Gorda.

The crew chief told Gardner that they already had the coordinates for the wreck.

The helicopter crew, with Gardner aboard, searched for two more hours but found nothing—nor did what, by now, was an even bigger search group that included a second H-60 helicopter, a C-130 fixed wing aircraft, the Coast Guard’s eighty-two-foot cutter Point Swift, and a forty-one-foot utility cruiser. The U.S. Coast Guard Auxiliary and other volunteers were also providing boats and crew, but the smaller vessels could not search offshore because the wind was now blowing twenty knots out of the east-northeast.

Hopes of recovering the three missing divers remained high, however. They were all young, all in good shape, and they were all wearing wet suits and inflated vests.

As one of the Coast Guard staff assured Gardner, “Don’t worry, we’re the very best in the world at finding people lost at sea.”

Which is true.

Descriere

A fun excursion for four divers off the Florida coast ends two days later when only one--a friend of Doc Ford's--is found alive. Doc thinks he's prepared for the truth about what happened. He's not.