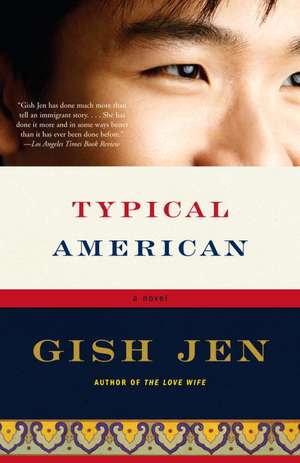

Typical American

Autor Gish Jenen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 dec 2007

Gish Jen reinvents the American immigrant story through the Chang family, who first come to the United States with no intention of staying. When the Communists assume control of China in 1949, though, Ralph Chang, his sister Theresa, and his wife Helen, find themselves in a crisis. At first, they cling to their old-world ideas of themselves. But as they begin to dream the American dream of self-invention, they move poignantly and ironically from people who disparage all that is “typical American” to people who might be seen as typically American themselves. With droll humor and a deep empathy for her characters, Gish Jen creates here a superbly engrossing story that resonates with wit and wisdom even as it challenges the reader to reconsider what a typical American might be today.

Preț: 90.95 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 136

Preț estimativ în valută:

17.41€ • 17.98$ • 14.49£

17.41€ • 17.98$ • 14.49£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307389220

ISBN-10: 0307389227

Pagini: 296

Dimensiuni: 132 x 203 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 0307389227

Pagini: 296

Dimensiuni: 132 x 203 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Notă biografică

Gish Jen is the author of the novels Typical American, Mona in the Promised Land, The Love Wife and Who’s Irish, a book of stories. Her honors include the Lannan Award for Fiction and the Strauss Living Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. She lives with her husband and two children in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Extras

A BOY

WITH HIS HANDS

OVER HIS EARS

IT'S AN American story: Before he was a thinker, or a doer, or an engineer, much less an imagineer like his self-made-millionaire friend Grover Ding, Ralph Chang was just a small boy in China, struggling to grow up his father's son. We meet him at age six. He doesn't know where or what America is, but he does know, already, that he's got round ears that stick out like the sideview mirrors of the only car in town--his father's. Often he wakes up to find himself tied by his ears to a bedpost, or else he finds loops of string around them, to which are attached dead bugs. "Earrings!" his cousins laugh. His mother tells him something like, It's only a phase. (This is in Shanghainese.) After a while the other boys will grow up, she says, he should ignore them. Until they grow up? he thinks, and instead--more sensibly--walks around covering his ears with his hands. He presses them back, hoping to train them to bring him less pain. Silly boy! Everyone teases him except his mother, who pleads patiently.

"That's not the way." She frowns. "Are you listening?"

He nods, hands over his ears.

"How can you listen with your hands over your ears?"

He shrugs. "I'm listening."

Back and forth. Until finally, irked, she says what his tutor always says, "You listen but don't hear!"--distinguishing, the way the Chinese will, between effort and result. Verbs in English are simple. One listens. After all, why should a listening person not hear? What's taken for granted in English, though, is spelled out in Chinese; there's even a verb construction for this purpose. Ting de jian in Mandarin means, one listens and hears. Ting bu jian means, one listens but fails to hear. People hear what they can, see what they can, do what they can; that's the understanding. It's an old culture talking. Everywhere there are limits.

As Ralph, who back then was not Ralph yet, but still Yifeng--Intent on the Peak--already knew. His mother wheedles, patient again. "No hands on your ears during lessons, okay? As it is, you have trouble enough." If he stops, she promises, she'll give him preserved plums, mooncakes, money. If he doesn't, "Do you realize your father will beat me too?"

"Lazy," says his father. "Stupid. What do you do besides eat and sleep all day?" The upright scholar, the ex--government official, calls him a fan tong--a rice barrel. He has an assignment for his son: Yifeng will please study his Older Sister. He will please observe everything she does, and simply copy her.

His Older Sister (Yifeng calls her Bai Xiao, Know-It-All) blushes.

Hands over his ears, Yifeng presses, presses, presses.

It's 1947; Yifeng's more or less grown up. The Anti-Japanese War has been over for two years. Now there's wreckage, and inflation, and moral collapse. Or so it seems to his father as, on a fan-cooled veranda, he entertains apocalyptic thoughts of marching armies, a new dynasty, the end of society as they know it.

"Might there be something nicer to talk about?" suggests his mother.

But his father will talk destruction and gloom if he wants to. Degeneracy! he says. Stupidity! Corruption! These have been his lifelong enemies; thanks to them he no longer holds office.

"Too much rice wine," muses Ralph's mother.

This is in a small town in Jiangsu province, outside Shanghai, a place of dusty shops and rutted roads, of timber and clay--a place where every noise has a known source. Somewhere in the city, the girl who will become Helen hums Western love songs to herself; on a convent school diamond, Know-It-All (that is, Theresa) fields grounders from her coach. Ralph, though--Yifeng--is on his way home from his job at the Transportation Department. His mother knows this. As his father prepares to write an article--he has an inkstone out, and a wolf's hair maobi--his mother prepares to speak up.

His father announces that he's going to write about Degeneracy! Stupidity! Corruption!

"America," his mother says then.

His father goes on grinding his ink. Yifeng simply cannot be going abroad.

"But it seems, perhaps, that he is."

Silence. His father's hand hovers over the inkstone, circling. He presses just so hard, no harder. He holds his ink stick upright.

A fellowship from the government! Field training! His son, an advanced engineer! No one knows what's possible like a father. His ink blackens; and in the end he can't be kept from making a few discreet inquiries, among friends. This is how he discovers that things are indeed more involved than they at first appeared. Though Yifeng has scored seventeenth on the department exam, he is one of the ten picked to go.

"No door like a back door," says his father.

"Your only son," pleads his mother.

His father looks away. "Opposites begin in one another," he says. And, "Yi dai qing qing, qi dai huai"--one generation pure, the next good for nothing.

Of course, in the end, Yifeng did come to the United States anyway, his stomach burbling with fool hope. But it was privately, not through the government, and not for advanced field training, but for graduate study. A much greater opportunity, as everyone agreed. He could bring back a degree!

"A degree," he echoed dully.

His mother arranged a send-off banquet, packed him a black trunk full of Western-style clothes.

"Your father would like to give you this," she told him at the dock. As his father stared off into the Shanghai harbor--at the true ships in the distance, the ragtag boats by the shore--she slid a wristwatch into Yifeng's hand.

Yifeng nodded. "I'll remember him always."

It was hot.

On the way to America, Yifeng studied. He reviewed his math, his physics, his English, struggling for long hours with his broken-backed books, and as the boat rocked and pitched he set out two main goals for himself. He was going to be first in his class, and he was not going home until he had his doctorate rolled up to hand his father. He also wrote down a list of subsidiary aims.

1. I will cultivate virtue. (A true scholar being a good scholar; as the saying went, there was no carving rotten wood.)

2. I will bring honor to the family.

What else?

3. I will do five minutes of calisthenics daily.

4. I will eat only what I like, instead of eating everything.

5. 1 will on no account keep eating after everyone else has stopped.

6. I will on no account have anything to do with girls.

On 7 through 10, he was stuck until he realized that number 6 about the girls was so important it counted for at least four more than itself. For girls, he knew, were what happened to even the cleverest, most diligent, most upright of scholars; the scholars kissed, got syphilis, and died without getting their degrees.

He studied in the sun, in the rain, by every shape moon. The ocean sang and spit; it threw itself on the deck. Still he studied. He studied as the horizon developed, finally, a bit of skin--land! He studied as that skin thickened, and deformed, and resolved, shaping itself as inevitably as a fetus growing eyes, growing ears. Even when islands began to heave their brown, bristled backs up through the sea (a morning sea so shiny it seemed to have turned into light and light and light), he watched only between pages. For this was what he'd vowed as a corollary of his main aim--to study until he could see the pylons of the Golden Gate Bridge.

That splendor! That radiance! True, it wasn't the Statue of Liberty, but still in his mind its span glowed bright, an image of freedom, and hope, and relief for the seasick. The day his boat happened into harbor, though, he couldn't make out the bridge until he was almost under it, what with the fog; and all there was to hear were foghorns. These honked high, low, high, low, over and over, like a demented musician playing his favorite two notes.

How was anyone supposed to be able to read?

Years later, when he told this story, he'd claim that the only sightseeing he did was to make a trip back to the bridge, in better weather, to have his picture taken. Unfortunately, he forgot his camera. As for the train ride to New York--famous mountains lumbered by, famous rivers, plains, canyons, the whole holy American spectacle, without his looking up once.

"So how'd you know what you were passing, then," his younger daughter would ask. (This was Mona, who was just like that, a mosquito.)

"I hear what other people talk," he'd say--at least usually. Once, though, he blushed. "I almost never take a look at." He shrugged, sheepish. "Interesting."

New York. He admitted that maybe he had taken a look around there too. And what of it? The idea city still gleamed then, after all, plus this was the city of cities, a place that promised to be recalled as an era. Ralph toured the century to date--its subway, its many mighty bridges, its highways. He was awed by the Empire State Building. Those pilings! He wondered at roller coasters, Ferris wheels. At cafeterias--eating factories, these seemed to him, most advanced and efficient, especially the Automats with their machines lit bright as a stage. The mundane details of life impressed him too--the neatly made milk cartons, the spring-loaded window shades, the electric iceboxes everywhere. Only he even saw these things, it seemed; only he considered how they had been made, the gears turning, the levers tilting. Even haircuts done by machine here! The very air smelled of oil. Nothing was made of bamboo.

He did notice.

By and large, though, he really did study. He studied as he walked, as he ate. The first week. The second week.

The third week, however, what could happen even to the cleverest, most diligent, most upright of scholars (and he was at least diligent, he allowed) happened to him.

"She was some--what you call?--tart," he said.

A BOY

WITH HIS HAT

OVER HIS CROTCH

PICTURE HIM. Young, orotund. Longish hair managed with grease. A new, light gray, too dressy, double-breasted suit made him look even shorter than his five feet three and three-quarter inches. Otherwise he was himself--large-faced, dimpled, with eyebrows that rode nervously up and up, away from his flat, wide, placid nose. He had small teeth set in vast expanses of gum; those round ears; and delicate, almost maidenly skin that tended to flush and pale with the waxing and waning of his digestive problems. Everywhere he went, he carried a Panama hat with him, though he never put it on, and it was always in his way; he seemed to have picked up an idea about gentlemen, or hats--something--that was proving hard to let go.

In sum, he was a doll, and the Foreign Student Affairs secretary, though she loathed her job, loathed her boss, loathed working, liked him.

"Name?" he repeated, or rather "nem," which he knew to be wrong. He turned red, thinking of his trouble with long a's, th's, l's, consonants at the ends of words. Was it beneath a scholar to hate the alphabet? Anyway, he did.

"Naaame," she said, writing it down. She'd seen this before, foreign students who could read and write and speak a little, but who just couldn't get the conversation. N-A-M-E.

"Name Y. F. Chang." (His surname as he pronounced it then sounded like the beginning of angst; it would be years before he was used to hearing Chang rhyme with twang.)

"Eng-lish-name," said Cammy. E-N-G-L-I-S-H-N-A-M-E.

"I Chin-ese," he said, and was about to explain that Y. F. were his initials when she laughed.

"Eng-lish-name," she said again.

"What you laughing?"

Later he realized this to be a very daring thing to ask, that he never would have asked a Chinese girl why she was laughing. But then, a Chinese girl never would have been laughing, not like that. Not a nice Chinese girl, anyway. What a country he was in!

"I'm laughing at you." Her voice rang, playful yet deeper than he would have expected. She smelled of perfume. He could not begin to guess her age. "At you!"

"Me?" With mock offense, he drew his chin back.

"You," she said again. "Me?" "You." "Me?" They were joking! In English! Shuo de chu--he spoke, and the words came out! Ting de dong--he listened and understood!

"English name," she said again, finally. She showed him her typewriter, the form she had to fill out.

"No English name." How to say initials? He was sorry to disappoint her. Then he brightened. "You give me."

"I-give-you-a-name?"

"Sure. You give." There was something about speaking English that carried him away.

"I'll-hang-onto-this-form-overnight," she tried to tell him.

"That-way-you-find-a-name-you-like-better-you-can-tell-me-tomorrow."

Too much, he didn't get it. Anyway, he waited, staring--exercising the outsider's privilege, to be rude. How colorful she was! Orange hair, pink face, blue eyes. Red nails. Green dress. And under the dress, breasts large and solid as earthworks. He thought of the burial mounds that dotted the Chinese countryside--the small mounds for nobodies, the big mounds for big shots. This woman put him in mind of the biggest mound he had ever seen: in Shandong, that was, Confucius's grave.

Meanwhile, she ran through her ex-beaux. Robert? Eugene? Norman? She toyed with a stray curl. Fred? John? Steve? Ken? "Ralph," she said finally. She wrote it down. R-A-L-P-H. "Do you like it?"

"Sure!" He beamed.

Walking home, though, Ralph was less sanguine. Had he been too hasty? He did this, he knew; he dispensed with things, trying to be like other people--decisive, practical--only to discover he'd overdone it. His stomach puckered with anxiety. And sure enough, when he asked around later he found that the other Chinese students (there were five of them in the master's degree program) had all stuck with their initials, or picked names for themselves, carefully, or else had wise people help them.

"Ralph," said smooth-faced Old Chao (Old Something-or-another being what younger classmates called older classmates, who in turn called them Little Something-or-another). He looked it up in a book he had. "Means wolf," he said, then looked that up in a dictionary. "A kind of dog," he translated.

A kind of dog, thought Ralph.

For himself, Old Chao had Henry, which turned out to be the name of at least eight kings. "My father picked it for me," he said.

It would have been better if Ralph sounded a bit more like Yifeng; in the art of picking English names (which everyone seemed to know except him), that was considered desirable. But so what? And who cared what it meant? Ralph decided that what was on the form didn't matter. He was a man with a mission; what mattered was that he register for the right courses, that he attend the right classes, that he buy the right books. All of this proved more difficult than he'd anticipated. He discovered, for instance, that he wasn't on the class list for two of his courses, and that for one of them, enrollment was already closed. To address these problems, he did what he did when his tuition didn't arrive, and when his other two classes turned out to meet at the same time: he found his way to the Foreign Student Affairs Office, where gaily colored Cammy would help him.

WITH HIS HANDS

OVER HIS EARS

IT'S AN American story: Before he was a thinker, or a doer, or an engineer, much less an imagineer like his self-made-millionaire friend Grover Ding, Ralph Chang was just a small boy in China, struggling to grow up his father's son. We meet him at age six. He doesn't know where or what America is, but he does know, already, that he's got round ears that stick out like the sideview mirrors of the only car in town--his father's. Often he wakes up to find himself tied by his ears to a bedpost, or else he finds loops of string around them, to which are attached dead bugs. "Earrings!" his cousins laugh. His mother tells him something like, It's only a phase. (This is in Shanghainese.) After a while the other boys will grow up, she says, he should ignore them. Until they grow up? he thinks, and instead--more sensibly--walks around covering his ears with his hands. He presses them back, hoping to train them to bring him less pain. Silly boy! Everyone teases him except his mother, who pleads patiently.

"That's not the way." She frowns. "Are you listening?"

He nods, hands over his ears.

"How can you listen with your hands over your ears?"

He shrugs. "I'm listening."

Back and forth. Until finally, irked, she says what his tutor always says, "You listen but don't hear!"--distinguishing, the way the Chinese will, between effort and result. Verbs in English are simple. One listens. After all, why should a listening person not hear? What's taken for granted in English, though, is spelled out in Chinese; there's even a verb construction for this purpose. Ting de jian in Mandarin means, one listens and hears. Ting bu jian means, one listens but fails to hear. People hear what they can, see what they can, do what they can; that's the understanding. It's an old culture talking. Everywhere there are limits.

As Ralph, who back then was not Ralph yet, but still Yifeng--Intent on the Peak--already knew. His mother wheedles, patient again. "No hands on your ears during lessons, okay? As it is, you have trouble enough." If he stops, she promises, she'll give him preserved plums, mooncakes, money. If he doesn't, "Do you realize your father will beat me too?"

"Lazy," says his father. "Stupid. What do you do besides eat and sleep all day?" The upright scholar, the ex--government official, calls him a fan tong--a rice barrel. He has an assignment for his son: Yifeng will please study his Older Sister. He will please observe everything she does, and simply copy her.

His Older Sister (Yifeng calls her Bai Xiao, Know-It-All) blushes.

Hands over his ears, Yifeng presses, presses, presses.

It's 1947; Yifeng's more or less grown up. The Anti-Japanese War has been over for two years. Now there's wreckage, and inflation, and moral collapse. Or so it seems to his father as, on a fan-cooled veranda, he entertains apocalyptic thoughts of marching armies, a new dynasty, the end of society as they know it.

"Might there be something nicer to talk about?" suggests his mother.

But his father will talk destruction and gloom if he wants to. Degeneracy! he says. Stupidity! Corruption! These have been his lifelong enemies; thanks to them he no longer holds office.

"Too much rice wine," muses Ralph's mother.

This is in a small town in Jiangsu province, outside Shanghai, a place of dusty shops and rutted roads, of timber and clay--a place where every noise has a known source. Somewhere in the city, the girl who will become Helen hums Western love songs to herself; on a convent school diamond, Know-It-All (that is, Theresa) fields grounders from her coach. Ralph, though--Yifeng--is on his way home from his job at the Transportation Department. His mother knows this. As his father prepares to write an article--he has an inkstone out, and a wolf's hair maobi--his mother prepares to speak up.

His father announces that he's going to write about Degeneracy! Stupidity! Corruption!

"America," his mother says then.

His father goes on grinding his ink. Yifeng simply cannot be going abroad.

"But it seems, perhaps, that he is."

Silence. His father's hand hovers over the inkstone, circling. He presses just so hard, no harder. He holds his ink stick upright.

A fellowship from the government! Field training! His son, an advanced engineer! No one knows what's possible like a father. His ink blackens; and in the end he can't be kept from making a few discreet inquiries, among friends. This is how he discovers that things are indeed more involved than they at first appeared. Though Yifeng has scored seventeenth on the department exam, he is one of the ten picked to go.

"No door like a back door," says his father.

"Your only son," pleads his mother.

His father looks away. "Opposites begin in one another," he says. And, "Yi dai qing qing, qi dai huai"--one generation pure, the next good for nothing.

Of course, in the end, Yifeng did come to the United States anyway, his stomach burbling with fool hope. But it was privately, not through the government, and not for advanced field training, but for graduate study. A much greater opportunity, as everyone agreed. He could bring back a degree!

"A degree," he echoed dully.

His mother arranged a send-off banquet, packed him a black trunk full of Western-style clothes.

"Your father would like to give you this," she told him at the dock. As his father stared off into the Shanghai harbor--at the true ships in the distance, the ragtag boats by the shore--she slid a wristwatch into Yifeng's hand.

Yifeng nodded. "I'll remember him always."

It was hot.

On the way to America, Yifeng studied. He reviewed his math, his physics, his English, struggling for long hours with his broken-backed books, and as the boat rocked and pitched he set out two main goals for himself. He was going to be first in his class, and he was not going home until he had his doctorate rolled up to hand his father. He also wrote down a list of subsidiary aims.

1. I will cultivate virtue. (A true scholar being a good scholar; as the saying went, there was no carving rotten wood.)

2. I will bring honor to the family.

What else?

3. I will do five minutes of calisthenics daily.

4. I will eat only what I like, instead of eating everything.

5. 1 will on no account keep eating after everyone else has stopped.

6. I will on no account have anything to do with girls.

On 7 through 10, he was stuck until he realized that number 6 about the girls was so important it counted for at least four more than itself. For girls, he knew, were what happened to even the cleverest, most diligent, most upright of scholars; the scholars kissed, got syphilis, and died without getting their degrees.

He studied in the sun, in the rain, by every shape moon. The ocean sang and spit; it threw itself on the deck. Still he studied. He studied as the horizon developed, finally, a bit of skin--land! He studied as that skin thickened, and deformed, and resolved, shaping itself as inevitably as a fetus growing eyes, growing ears. Even when islands began to heave their brown, bristled backs up through the sea (a morning sea so shiny it seemed to have turned into light and light and light), he watched only between pages. For this was what he'd vowed as a corollary of his main aim--to study until he could see the pylons of the Golden Gate Bridge.

That splendor! That radiance! True, it wasn't the Statue of Liberty, but still in his mind its span glowed bright, an image of freedom, and hope, and relief for the seasick. The day his boat happened into harbor, though, he couldn't make out the bridge until he was almost under it, what with the fog; and all there was to hear were foghorns. These honked high, low, high, low, over and over, like a demented musician playing his favorite two notes.

How was anyone supposed to be able to read?

Years later, when he told this story, he'd claim that the only sightseeing he did was to make a trip back to the bridge, in better weather, to have his picture taken. Unfortunately, he forgot his camera. As for the train ride to New York--famous mountains lumbered by, famous rivers, plains, canyons, the whole holy American spectacle, without his looking up once.

"So how'd you know what you were passing, then," his younger daughter would ask. (This was Mona, who was just like that, a mosquito.)

"I hear what other people talk," he'd say--at least usually. Once, though, he blushed. "I almost never take a look at." He shrugged, sheepish. "Interesting."

New York. He admitted that maybe he had taken a look around there too. And what of it? The idea city still gleamed then, after all, plus this was the city of cities, a place that promised to be recalled as an era. Ralph toured the century to date--its subway, its many mighty bridges, its highways. He was awed by the Empire State Building. Those pilings! He wondered at roller coasters, Ferris wheels. At cafeterias--eating factories, these seemed to him, most advanced and efficient, especially the Automats with their machines lit bright as a stage. The mundane details of life impressed him too--the neatly made milk cartons, the spring-loaded window shades, the electric iceboxes everywhere. Only he even saw these things, it seemed; only he considered how they had been made, the gears turning, the levers tilting. Even haircuts done by machine here! The very air smelled of oil. Nothing was made of bamboo.

He did notice.

By and large, though, he really did study. He studied as he walked, as he ate. The first week. The second week.

The third week, however, what could happen even to the cleverest, most diligent, most upright of scholars (and he was at least diligent, he allowed) happened to him.

"She was some--what you call?--tart," he said.

A BOY

WITH HIS HAT

OVER HIS CROTCH

PICTURE HIM. Young, orotund. Longish hair managed with grease. A new, light gray, too dressy, double-breasted suit made him look even shorter than his five feet three and three-quarter inches. Otherwise he was himself--large-faced, dimpled, with eyebrows that rode nervously up and up, away from his flat, wide, placid nose. He had small teeth set in vast expanses of gum; those round ears; and delicate, almost maidenly skin that tended to flush and pale with the waxing and waning of his digestive problems. Everywhere he went, he carried a Panama hat with him, though he never put it on, and it was always in his way; he seemed to have picked up an idea about gentlemen, or hats--something--that was proving hard to let go.

In sum, he was a doll, and the Foreign Student Affairs secretary, though she loathed her job, loathed her boss, loathed working, liked him.

"Name?" he repeated, or rather "nem," which he knew to be wrong. He turned red, thinking of his trouble with long a's, th's, l's, consonants at the ends of words. Was it beneath a scholar to hate the alphabet? Anyway, he did.

"Naaame," she said, writing it down. She'd seen this before, foreign students who could read and write and speak a little, but who just couldn't get the conversation. N-A-M-E.

"Name Y. F. Chang." (His surname as he pronounced it then sounded like the beginning of angst; it would be years before he was used to hearing Chang rhyme with twang.)

"Eng-lish-name," said Cammy. E-N-G-L-I-S-H-N-A-M-E.

"I Chin-ese," he said, and was about to explain that Y. F. were his initials when she laughed.

"Eng-lish-name," she said again.

"What you laughing?"

Later he realized this to be a very daring thing to ask, that he never would have asked a Chinese girl why she was laughing. But then, a Chinese girl never would have been laughing, not like that. Not a nice Chinese girl, anyway. What a country he was in!

"I'm laughing at you." Her voice rang, playful yet deeper than he would have expected. She smelled of perfume. He could not begin to guess her age. "At you!"

"Me?" With mock offense, he drew his chin back.

"You," she said again. "Me?" "You." "Me?" They were joking! In English! Shuo de chu--he spoke, and the words came out! Ting de dong--he listened and understood!

"English name," she said again, finally. She showed him her typewriter, the form she had to fill out.

"No English name." How to say initials? He was sorry to disappoint her. Then he brightened. "You give me."

"I-give-you-a-name?"

"Sure. You give." There was something about speaking English that carried him away.

"I'll-hang-onto-this-form-overnight," she tried to tell him.

"That-way-you-find-a-name-you-like-better-you-can-tell-me-tomorrow."

Too much, he didn't get it. Anyway, he waited, staring--exercising the outsider's privilege, to be rude. How colorful she was! Orange hair, pink face, blue eyes. Red nails. Green dress. And under the dress, breasts large and solid as earthworks. He thought of the burial mounds that dotted the Chinese countryside--the small mounds for nobodies, the big mounds for big shots. This woman put him in mind of the biggest mound he had ever seen: in Shandong, that was, Confucius's grave.

Meanwhile, she ran through her ex-beaux. Robert? Eugene? Norman? She toyed with a stray curl. Fred? John? Steve? Ken? "Ralph," she said finally. She wrote it down. R-A-L-P-H. "Do you like it?"

"Sure!" He beamed.

Walking home, though, Ralph was less sanguine. Had he been too hasty? He did this, he knew; he dispensed with things, trying to be like other people--decisive, practical--only to discover he'd overdone it. His stomach puckered with anxiety. And sure enough, when he asked around later he found that the other Chinese students (there were five of them in the master's degree program) had all stuck with their initials, or picked names for themselves, carefully, or else had wise people help them.

"Ralph," said smooth-faced Old Chao (Old Something-or-another being what younger classmates called older classmates, who in turn called them Little Something-or-another). He looked it up in a book he had. "Means wolf," he said, then looked that up in a dictionary. "A kind of dog," he translated.

A kind of dog, thought Ralph.

For himself, Old Chao had Henry, which turned out to be the name of at least eight kings. "My father picked it for me," he said.

It would have been better if Ralph sounded a bit more like Yifeng; in the art of picking English names (which everyone seemed to know except him), that was considered desirable. But so what? And who cared what it meant? Ralph decided that what was on the form didn't matter. He was a man with a mission; what mattered was that he register for the right courses, that he attend the right classes, that he buy the right books. All of this proved more difficult than he'd anticipated. He discovered, for instance, that he wasn't on the class list for two of his courses, and that for one of them, enrollment was already closed. To address these problems, he did what he did when his tuition didn't arrive, and when his other two classes turned out to meet at the same time: he found his way to the Foreign Student Affairs Office, where gaily colored Cammy would help him.

Recenzii

“Gish Jen has done much more than tell an immigrant story. . . . She has done it more and in some ways better than it has ever been done before.” —Los Angeles Times Book Review

“The immigrant experience will never be the same. . . . A comedy . . . a tragedy . . . a pure delight.” —The Boston Globe

“An irresistible novel . . . suspenseful, startling, heartrending, without ever losing its comic touch.” —Entertainment Weekly

“No paraphrase could capture the intelligence of Gish Jen’s prose, its epigrammatic sweep and swiftness. . . . The author just keeps coming at you line after stunning line.” —The New York Times Book Review

“The immigrant experience will never be the same. . . . A comedy . . . a tragedy . . . a pure delight.” —The Boston Globe

“An irresistible novel . . . suspenseful, startling, heartrending, without ever losing its comic touch.” —Entertainment Weekly

“No paraphrase could capture the intelligence of Gish Jen’s prose, its epigrammatic sweep and swiftness. . . . The author just keeps coming at you line after stunning line.” —The New York Times Book Review

Descriere

This wonderful, bittersweet novel of misadventure and creeping assimilation begins in 1947, when the Shanghai-based Changs send young Ralph halfway around the world to study in New York. He sets off with two goals in mind--to master engineering and to avoid girls at any cost.