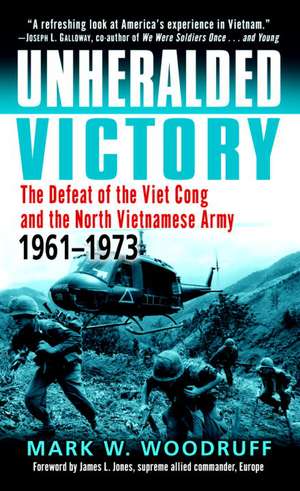

Unheralded Victory: The Defeat of the Viet Cong and the North Vietnamese Army, 1961-1973

Autor Mark W. Woodruff James L Jonesen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 sep 2005

Preț: 51.92 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 78

Preț estimativ în valută:

9.93€ • 10.37$ • 8.22£

9.93€ • 10.37$ • 8.22£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780891418665

ISBN-10: 0891418660

Pagini: 394

Dimensiuni: 107 x 176 x 29 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: Presidio Press

ISBN-10: 0891418660

Pagini: 394

Dimensiuni: 107 x 176 x 29 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: Presidio Press

Notă biografică

Mark W. Woodruff enlisted in the Marine Corps in July 1967, serving in Vietnam with Foxtrot Company, 2nd Battalion, 3rd Marine Regiment from December 1967 to December 1968. After leaving the Marine Corps, he received his B.A. and M.A. in psychology from Pepperdine University in California. He is now a lieutenant commander in the Royal Australian Navy and a psychologist with the Vietnam Veterans Counseling Service in Perth, Australia. He is also the author of Foxtrot Ridge.

Extras

Two Different Countries, Many Different Wars

Most Americans seem accustomed to using the term “the Vietnam War” to describe the period of American involvement there. In so doing, Americans ignore the centuries of conflict before America became involved and the decades of continuing conflict after America withdrew in 1973. In fact, the recorded history of what is now known as “Vietnam” began in 207 B.C. when a Chinese warlord named Trieu Da established the kingdom of Nam Viet, extending from the area now known as Da Nang northward to southern China. In 111 B.C., the Chinese under Han emperor, Wu Ti, laid claim and ruled for the next thousand years. The separate kingdom of Champa lay to the south running from Nam Viet to the Mekong Delta.1

While the Chinese dominated the northern kingdom of Nam Viet, the southern kingdom of Champa was Hindu and influenced by India. Further to the west, and also on the extreme southern tip, lay another Hindu kingdom, Funan, conquered by the Mon-Khymer people of the Cambodian empire in the 6th century.

The southern kingdom of Champa was often at war with the northern kingdom of Nam Viet, but maintained a separate identity until being conquered by Nam Viet in 1471. Saigon and the Mekong Delta were taken from Cambodia during the period 1700–1760. Although nominally ruled by the Le dynasty, this area, which occupies the rough geographical boundaries known today as “Vietnam,” continued to be divided, ruled by the Trinh family in the north and the Nguyen family in the south.

Throughout the 17th century, the animosity between the people of the north and the people of the south was so great that a long and bloody war ensued between them. Between 1627 and 1673, the aggressive Trinh emperors of the north tried seven different times to invade the south, but each time they were stopped by the Nguyens’ defenses. The southerners had constructed two 20-foot-high walls, one of them six miles long and the other twenty miles long at the point where the coastal plain was at its narrowest: the 17th parallel. In the late 1700s, the northerners briefly prevailed but a survivor of the southern family, Nguyen Anh, occupied Saigon and the Mekong Delta. After a 14-year struggle, the southerners seized Hue and Hanoi with French military aid. In 1802, Nguyen Anh assumed the throne as Emperor Gia Long of a united Vietnam.

Gia Long’s successors, however, distrusted the French and, more specifically, their Christianity and, by 1820, they were expelling French missionaries and imprisoning or executing Vietnamese converts to Christianity. The French responded militarily and, with Napoleon III on the French throne, set about establishing French colonial rule. This French intervention superseded domestic, north-versus-south politics for over 100 years, commencing in 1847. Although occupied by the Japanese in World War II, the French quickly reestablished control at the end of the war. The Communist Viet Minh forces, which had fought against the Japanese, now turned their attention to the French.

Weapons captured by the Communist Chinese in Korea began to flow to the Viet Minh in the early 1950s. The French and their Vietnamese allies fought a seesaw battle with the Viet Minh forces. In France itself, the French Communist Party was a major political force committed to the support of the Viet Minh. America, concerned about the Soviet threat to Europe and keen to have a strong, non-Communist France, increasingly financed the French effort but stayed out of direct involvement.

The French eventually tired of the struggle, disheartened by their defeat in the battle of Dien Bien Phu, which took place deep in the north of the country. A cease-fire was signed in Geneva in 1954, establishing the 17th parallel, that same narrow stretch of coastal plain where the Nguyens had built their defensive walls and previously fought the northerners, as the border separating the southern Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam) and the northern Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam). Elections were scheduled to be held in two years.

While the French had tired of the struggle and no longer backed the fight, the Communists, too, had suffered massively in their battles. Nikita Khrushchev’s memoirs make it clear that the Communist troops were at the point of exhaustion and needed the cease-fire in order to regroup and rebuild. Even their own official history, written in 1970, makes reference to the fact that the Communists were not then strong enough to seize the whole of Vietnam.2

Ho Chi Minh’s government was installed in North Vietnam, while the government of one-time emperor (1925–1945) Bao Dai was installed in South Vietnam. While it is often said that Ho Chi Minh could have won an election in 1954, when South Vietnam was in chaos and he was riding a crest of popularity from having ousted the French, the situation changed quickly. Within a few weeks, 850,000 people fled from North Vietnam to South Vietnam, most of them Catholics and small landowners fearful of the Communists. Only some 80,000 people went to the North, almost all of them guerrilla cadres who had fought the French.3

The actual effect of this massive population shift was never tested at the polls. The elections were not held. South Vietnam, which had not signed the Geneva Accords, did not believe the Communists in North Vietnam would allow a fair election. In January 1957, the International Control Commission (ICC), comprising observers from India, Poland, and Canada, agreed with this perception, reporting that neither South nor North Vietnam had honored the armistice agreement. With the French gone, a return to the traditional power struggle between north and south had begun again. At the 15th Meeting of the Party’s Central Committee in May of 1959, North Vietnam formally decided to take up arms against the government of South Vietnam.4

The war against South Vietnam was fought by the Hanoi-backed, southern-born Viet Cong as well as directly by the North Vietnamese Army itself. The goals of the Viet Cong and North Vietnam were parallel but not identical. The Viet Cong sought to achieve power in South Vietnam; the North Vietnamese sought to annex the South and “unify” Vietnam. Viet Cong Minister of Justice, Truong Nhu Tang, summed up the Southern viewpoint by saying that historically “. . . there were substantial economic, social, and cultural distinctions between North and South (let alone the ethnic minority regions) that argue for a regional rather than a centralized approach to unity.” But North Vietnam, despite its protestations at the time, sought to have both North and South Vietnam ruled under the North Vietnamese flag. The two forces’ “marriage of convenience” would last only briefly; but, while it did, they would mount savage attacks on South Vietnam.5

Unlike the French previously, the United States in the 1960s did not seek colonies or an empire. Rather, the United States was committed to backing any nation that opposed Communism. The Korean War was still fresh in American memories and only an uneasy truce had stopped the fighting there. Soviet tanks had crushed the Hungarian revolution only five years before and now sat poised to launch an attack against western Europe. Tensions in Europe were at their peak. Within months these tensions would result in building the Berlin Wall dividing Communist East from democratic West. With this backdrop of global military confrontation between the superpowers, President John F. Kennedy viewed the situation in South Vietnam with increasing concern as spring turned to summer in 1961.

Most Americans seem accustomed to using the term “the Vietnam War” to describe the period of American involvement there. In so doing, Americans ignore the centuries of conflict before America became involved and the decades of continuing conflict after America withdrew in 1973. In fact, the recorded history of what is now known as “Vietnam” began in 207 B.C. when a Chinese warlord named Trieu Da established the kingdom of Nam Viet, extending from the area now known as Da Nang northward to southern China. In 111 B.C., the Chinese under Han emperor, Wu Ti, laid claim and ruled for the next thousand years. The separate kingdom of Champa lay to the south running from Nam Viet to the Mekong Delta.1

While the Chinese dominated the northern kingdom of Nam Viet, the southern kingdom of Champa was Hindu and influenced by India. Further to the west, and also on the extreme southern tip, lay another Hindu kingdom, Funan, conquered by the Mon-Khymer people of the Cambodian empire in the 6th century.

The southern kingdom of Champa was often at war with the northern kingdom of Nam Viet, but maintained a separate identity until being conquered by Nam Viet in 1471. Saigon and the Mekong Delta were taken from Cambodia during the period 1700–1760. Although nominally ruled by the Le dynasty, this area, which occupies the rough geographical boundaries known today as “Vietnam,” continued to be divided, ruled by the Trinh family in the north and the Nguyen family in the south.

Throughout the 17th century, the animosity between the people of the north and the people of the south was so great that a long and bloody war ensued between them. Between 1627 and 1673, the aggressive Trinh emperors of the north tried seven different times to invade the south, but each time they were stopped by the Nguyens’ defenses. The southerners had constructed two 20-foot-high walls, one of them six miles long and the other twenty miles long at the point where the coastal plain was at its narrowest: the 17th parallel. In the late 1700s, the northerners briefly prevailed but a survivor of the southern family, Nguyen Anh, occupied Saigon and the Mekong Delta. After a 14-year struggle, the southerners seized Hue and Hanoi with French military aid. In 1802, Nguyen Anh assumed the throne as Emperor Gia Long of a united Vietnam.

Gia Long’s successors, however, distrusted the French and, more specifically, their Christianity and, by 1820, they were expelling French missionaries and imprisoning or executing Vietnamese converts to Christianity. The French responded militarily and, with Napoleon III on the French throne, set about establishing French colonial rule. This French intervention superseded domestic, north-versus-south politics for over 100 years, commencing in 1847. Although occupied by the Japanese in World War II, the French quickly reestablished control at the end of the war. The Communist Viet Minh forces, which had fought against the Japanese, now turned their attention to the French.

Weapons captured by the Communist Chinese in Korea began to flow to the Viet Minh in the early 1950s. The French and their Vietnamese allies fought a seesaw battle with the Viet Minh forces. In France itself, the French Communist Party was a major political force committed to the support of the Viet Minh. America, concerned about the Soviet threat to Europe and keen to have a strong, non-Communist France, increasingly financed the French effort but stayed out of direct involvement.

The French eventually tired of the struggle, disheartened by their defeat in the battle of Dien Bien Phu, which took place deep in the north of the country. A cease-fire was signed in Geneva in 1954, establishing the 17th parallel, that same narrow stretch of coastal plain where the Nguyens had built their defensive walls and previously fought the northerners, as the border separating the southern Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam) and the northern Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam). Elections were scheduled to be held in two years.

While the French had tired of the struggle and no longer backed the fight, the Communists, too, had suffered massively in their battles. Nikita Khrushchev’s memoirs make it clear that the Communist troops were at the point of exhaustion and needed the cease-fire in order to regroup and rebuild. Even their own official history, written in 1970, makes reference to the fact that the Communists were not then strong enough to seize the whole of Vietnam.2

Ho Chi Minh’s government was installed in North Vietnam, while the government of one-time emperor (1925–1945) Bao Dai was installed in South Vietnam. While it is often said that Ho Chi Minh could have won an election in 1954, when South Vietnam was in chaos and he was riding a crest of popularity from having ousted the French, the situation changed quickly. Within a few weeks, 850,000 people fled from North Vietnam to South Vietnam, most of them Catholics and small landowners fearful of the Communists. Only some 80,000 people went to the North, almost all of them guerrilla cadres who had fought the French.3

The actual effect of this massive population shift was never tested at the polls. The elections were not held. South Vietnam, which had not signed the Geneva Accords, did not believe the Communists in North Vietnam would allow a fair election. In January 1957, the International Control Commission (ICC), comprising observers from India, Poland, and Canada, agreed with this perception, reporting that neither South nor North Vietnam had honored the armistice agreement. With the French gone, a return to the traditional power struggle between north and south had begun again. At the 15th Meeting of the Party’s Central Committee in May of 1959, North Vietnam formally decided to take up arms against the government of South Vietnam.4

The war against South Vietnam was fought by the Hanoi-backed, southern-born Viet Cong as well as directly by the North Vietnamese Army itself. The goals of the Viet Cong and North Vietnam were parallel but not identical. The Viet Cong sought to achieve power in South Vietnam; the North Vietnamese sought to annex the South and “unify” Vietnam. Viet Cong Minister of Justice, Truong Nhu Tang, summed up the Southern viewpoint by saying that historically “. . . there were substantial economic, social, and cultural distinctions between North and South (let alone the ethnic minority regions) that argue for a regional rather than a centralized approach to unity.” But North Vietnam, despite its protestations at the time, sought to have both North and South Vietnam ruled under the North Vietnamese flag. The two forces’ “marriage of convenience” would last only briefly; but, while it did, they would mount savage attacks on South Vietnam.5

Unlike the French previously, the United States in the 1960s did not seek colonies or an empire. Rather, the United States was committed to backing any nation that opposed Communism. The Korean War was still fresh in American memories and only an uneasy truce had stopped the fighting there. Soviet tanks had crushed the Hungarian revolution only five years before and now sat poised to launch an attack against western Europe. Tensions in Europe were at their peak. Within months these tensions would result in building the Berlin Wall dividing Communist East from democratic West. With this backdrop of global military confrontation between the superpowers, President John F. Kennedy viewed the situation in South Vietnam with increasing concern as spring turned to summer in 1961.

Recenzii

“An inspired–and long-overdue–reexamination of the scoreboard from the much-disputed Southeast Asian war games played by a generation of Americans who served in Vietnam.”

–Dale A. Dye, Captain (Ret.), U.S. Marine Corps

“An informative read that will stir your emotions and keep your interest.”

–Leatherneck

“An extremely useful –and important–book.”

–Marine Corps Gazette

–Dale A. Dye, Captain (Ret.), U.S. Marine Corps

“An informative read that will stir your emotions and keep your interest.”

–Leatherneck

“An extremely useful –and important–book.”

–Marine Corps Gazette

Descriere

This carefully analyzed perspective on the Vietnam War makes a compelling case for the tactical victory of the allied military over the Viet Cong and the North Vietnamese Army throughout the conflict.