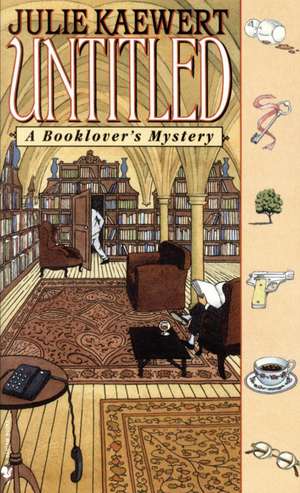

Untitled

Autor Julie Kaewerten Limba Engleză Paperback – 2 noi 1999

Publisher Alex Plumtree is in for the most astounding week of his life. First he comes into possession of a rare, centuries-old book, rumored destroyed on orders of King Edward IV. Then he receives an undreamed-of honor: an invitation to join a select society of book collectors...who are also some of the most powerful men and women in England.

But Alex's triumph quickly turns sour. The book vanishes from Alex's office. His initiation weekend with the Dibdin Club is rife with bizarre behavior, appalling accidents--and a death that sends Alex reeling. He quickly begins to suspect that his valuable find is even more than it seemed on first glance. For hidden in its pages is a shocking secret that could change the history of books forever...as well as the face of the modern world. And there are people--and foreign powers--who would do anything to keep this secret from coming to light.

All Alex has to do is figure out what that secret is. If he can stay alive long enough.

Preț: 45.35 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 68

Preț estimativ în valută:

8.68€ • 9.10$ • 7.22£

8.68€ • 9.10$ • 7.22£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 11-25 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780553577174

ISBN-10: 0553577174

Pagini: 338

Dimensiuni: 107 x 175 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.16 kg

Editura: PENGUIN RANDOM HOUSE LLC

ISBN-10: 0553577174

Pagini: 338

Dimensiuni: 107 x 175 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.16 kg

Editura: PENGUIN RANDOM HOUSE LLC

Extras

A room without books is like a body without a soul.

--Cicero

Finding the world's rarest book in my library that Sunday afternoon was a bibliophile's dream. But now I'd give anything if I hadn't caught a glimpse of its hiding place behind my bookshelves. For while that outwardly charming volume fascinated and delighted the bibliomaniac world, it held dangerous secrets--secrets that not only ignited hostilities that had simmered for a millennium, but took from me everything I held most precious.

On that unforgettable afternoon I sat at my desk in the library, scrawling American addresses on ivory wedding invitation envelopes--hundreds of them. Sarah Townsend, my intended, had insisted my handwriting was infinitely preferable to that of the commercial calligraphers she knew. I wasn't sure I agreed, but anything for Sarah. A few hundred envelopes? Delighted, my love.

It was also infinitely preferable to the nasty task of home maintenance that awaited me outside. One of our ancient oaks, which had been ailing for several years, had keeled over against the house in a violent gale the previous week. It was still perched there, waiting to cause a new disaster. I'd intended to get to it that weekend, but . . .

The doorbell rang. I checked my watch as I rose and went to the door, stretching luxuriously. Four o'clock on a Sunday afternoon. The Sunday Times was still strewn about the sofa in pleasant disarray, its rumours of deepening hostilities between America and Iraq as remote as those faraway deserts. Even the lesser evil of a flu epidemic in London seemed remote, with the roses blooming and the birds singing outside the open French doors. Ah, but life was good here at the Orchard, long the family home of the Plumtree clan. The oak could wait. And it was time for tea.

I swung open the door, enjoying its characteristic creak on the old hinge.

"Max!" I exclaimed. "What a pleasant surprise. I was just going to put the kettle--"

"Sorry, Alex." My brother pushed past me, all business, into the hallway. "I need to borrow a book, if you don't mind. Sorry to disturb."

"Not at all," I murmured. I closed the front door and followed him into the library. I was used to Max's brief enthusiasms, his frequent small emergencies. I understood him well: He was simply a more concentrated version of myself. Emotionally, Max was more mercurial; physically, he was smaller and darker. He went straight to the shelf of reference books.

I watched him, as I leaned against my desk. "I've just been addressing the invitations for the Nantucket ceremony," I began to explain.

"Ah," he said distractedly, clearly not hearing a word I'd said. The vows I would take in little more than two months were not uppermost in his mind.

"I read in the paper this morning that aliens contacted the Queen. They spoke through her corgis at a polo match in Windsor Great Park."

"That's nice," he muttered, continuing to search through the richly stocked shelves--a bit wildly, it seemed to me. He was certainly in a flap about something.

"Not there," he said. "Damn! A client of mine--an anonymous one, funnily enough--said he'd already tried Maggs. They couldn't help him. So if I could, it'd be a coup. And I know we had that volume here . . . that heraldry volume Dad was forever showing us. I won't sell ours, of course, but at least my client could see it. And," Max said with exaggerated emphasis, quite pleased with himself, "if I have to meet with him, I can find out who he is. The book was a private issue, you know, a Dibdin Club edition. I have the impression he's after a more modern volume than the one we have, but I can't exactly remember the date of ours."

"Yes, I know the one you mean. It must be here somewhere." I went to a different wall of shelves to help him look; we had a very relaxed system of ordering our books, which allowed us the thrill of a treasure hunt each time we looked for an uncommon volume. And a Dibdin edition was a treasure . . . the Dibdin Club was the most prestigious group of bibliophiles in all England. Each year, one member chose an exceedingly rare volume from his or her own library and reissued it for the other members. It was a bit like a printing society, only less bourgeois and far more private. The Dibdin stopped just short of royalty, and its members held the loftiest titles--and books--in the land.

"Ah-ha!" Max cried, triumphantly snatching a large volume off the shelf.

"What's that?" I asked, squinting at the bookshelves. I went across to my brother, suddenly intrigued.

"Really, Alex!" Max rolled his eyes in exasperation. "I know you're busy with the wedding, my boy, but the world does carry on. I just told you it was the

Dibdin edition on heraldry, which I'd--"

"No, no, sorry. I mean what"--I bent down to reach to the back of the shelf--"is this?"

I knelt and lifted out several other books, placing them on the floor. Then I studied the wall behind the bookshelf more carefully. At this hour and season the sun was on the shelf directly; normally, I would have drawn the curtains by now to shield the spines from excessive light. "I do believe," I said, following a rectangular outline cut into the wood with my fingertips, "that there's something here."

I pushed on the rectangle, and it sprang outward toward me, opening on a hinge at its left edge. "I don't believe this," Max said incredulously, kneeling next to me and breathing down my neck. "Dad had another safe in the shelves?"

I wanted a torch; it was dark in the space, and I didn't fancy sticking my hand inside without knowing what was there. But I couldn't wait. I reached in and found that the area was quite small, perhaps twelve inches wide by eight deep. My fingers met with a hard object that felt very much like--why was I surprised?--a book. I pulled it out. Max and I found ourselves staring at a smallish volume, perhaps eight by six inches and half an inch thick.

"What are you doing here, then?" I said under my breath to the book.

Having something just short of an obsession with antiquarian books, I knew instantly that this was not any old volume. Its covers were upholstered with wine-red-velvet fabric. The covers and book itself were bound together with leather thongs; the binding of a very old book indeed--an incunable, in fact, a book from the cradle period of printing in the late fifteenth century. Book collectors positively salivated over such books, and often paid a great deal of money for them. Most were carefully preserved in museums.

Max and I exchanged a glance.

There was no title in the velvet on the front cover. I turned the book over and saw that the back cover was blank as well. The spine, too, was utterly devoid of print or decoration. Carefully, I lifted the cover to discover pristine, creamy-white rag paper. Rag, unlike modern woody stuff, held up miraculously well over the centuries without so much as discolouring.

"Good Lord," Max murmured as we stared down at the words on the page. "This is incredible. Look at that black letter--and you can see that they dampened the paper, which made a very deep impression. Alex, this is unquestionably an incunable."

"You're right. And look at the binding--definitely English. They've put the straps and clasps from the bottom up instead of the continental bottom down."

On the fine page before us, set in thick Gothic black-letter type, were the words:

DOMINUS SERVET VERITATEM ET VIRUM QUI EAM SCRIBIT

The remnants of my school Latin struggled to organise themselves into a translation. "God preserve the truth, and the man who writes--or prints?--it. . . . most unusual," I said.

"Mmm," Max replied. I knew he'd noticed, too, that there was no forematter, no early pages listing author, printer, or binder. Nor was there any date, though the heavy black-letter print and primitive printing process told us the book was likely to be fifteenth century. Just the rather dire Latin verse, followed by several blank pages.

Eagerly, I turned another page and found more black ink. The dark Gothic words opposed a breathtaking woodcut print of a knight in armour. A coat of arms ornamented the cloth covering his chain mail. He stood facing the reader, sword and shield in hand, features hidden by the metal helmet, and I noticed that a tiny four-poster was one of the symbols in the design on his chest. As best I could translate from Middle English the print opposite the woodcut of the knight, it said:

This is the story of the Royal Order of the Bedchamber, the loyal group of men who have pledged their lives to protect the King over the last three hundred years. We wish to tell the Order's history, and important historical facts known for centuries only to members of the Royal Order of the Bedchamber. These facts have never before been revealed, and were preserved by word of mouth within the Order until Giovanni Boccaccio became acquainted with a member of the Order, was captivated by the story, and wrote it down in 1371. We have printed it now thanks to the miracle of the printing press. We pray that no offence will be taken by His Majesty, King Edward IV, from our effort to record this magnificent truth.

So the book I held in my hands was an account of the daily activities of the knights of the Royal Order of the Bedchamber, evidently the king's closest and most loyal protectors. I'd never heard of them, but that didn't mean they couldn't have existed. I looked at Max. "Late fifteenth century, then, if the reigning monarch was Edward IV. But why would he take offence? It almost sounds as if the author expected the king to be displeased."

Max shrugged impatiently. "Let's have a look through the rest."

I turned through the remaining pages. The book contained only sixteen leaves; the last featured a stunningly detailed illustration, again from a woodcut, of a small four-poster surrounded by curtains. A knight knelt next to the bed dramatically, dripping dagger drawn at his side, a rampant lion with a crown in its teeth posturing aggressively on the coat of arms on his chest.

The pattern in the fabric of the bed curtains consisted of so many cross-hatchings that at first glance my eye imagined a multitude of nearly microscopic letters jumbled together and crossed by fine lines. When I looked more closely, I couldn't distinguish any letters at all. Holding the book a bit farther away, I blinked and looked again, trying to sort out the tiny patterns my eye perceived.

Not letters after all, I decided, but merely a design of overwhelming detail and precision, not to mention beauty. I turned back to the beginning to read the book's text. There was really very little print; a huge initial capital letter began the scant lines of text on each page.

It is the duty of each Knight of the Order to make the King safe, to guard his Bedchamber while he is sleeping, to taste his wine, water and mead before allowing him to drink. All Knights of the Order are sworn to give their lives before allowing any harm to come to His Majesty.

I turned another page.

For this reason the Knights of the Order are considered the bravest and most faithful of the realm. Because the King is appointed by God to reign over His people, the Knights serve God as well as the King. And so the tale I am about to relate is all the more tragic, because a Knight failed in his duty to both God and King.

The book went on for a bit here about the traditions of the Order, the specific duties of the knights and how they were carried out. I could hear Max breathing aloud as he too read. Then there came a fascinating bit about King Richard the Lion-Heart and the Crusades:

One of the most worrisome periods for the Knights of the Order was the Crusades. The Knights found themselves deeply suspicious of Saladin, the Sultan of Babylon with whom Richard established a firm friendship and even a truce in the Second Crusade. Every day the Knights expected the Saracen to commit some act of treachery toward their King, but this never came to pass. The unlikely friendship between the two rulers extended so far that King Richard offered his sister Joanna's hand in marriage to Saladin's brother, Al-Adil, as a peace offering. In the end, it was King Richard who grew tired of waiting for Saladin to deliver certain monies and the True Cross of Christ as agreed. It was our own King who broke the truce and slaughtered Saladin's people.

I read on, fascinated at this view of history through the knight's eyes. Several anecdotes later, I found a stunner:

Legend has held for hundreds of years that Richard the Lion-Heart died of a crossbow wound from a common poacher, after a disagreement with a peasant about some old coins the peasant had unearthed. This is not true; we wish the truth to be known. His Majesty lay abed for some time, recovering from his wound, which had unfortunately festered. As the noble Knight of the Order of the Bedchamber watched from behind the bed curtains one night, ever vigilant on behalf of his monarch, the Master of the Order crept in to the room.

Now, there was no reason for anyone to enter his Bedchamber at that hour unless they meant him harm. But the Master of the Order of the Bedchamber was much trusted and not a little feared, as it was known he had a violent temper, and his close relationship with His Majesty had never been doubted. True, his lands had been revoked with his title that spring over some perceived lack of loyalty, but the Master of the Order had seemed repentant for whatever had caused his penury and humiliation.

The Knight watched from behind the bed as the Master advanced and searched the Bedchamber for members of the Order such as himself. Seeing no one, and neglecting to look in the one spot the guarding Knight occupied, he proceeded to genuflect and kneel silently at the King's bedside.

Then, as the Knight guarded His Majesty silently from behind the curtain on the far side of the bed, he perceived that the Master of the Order made a subtle movement. While the Knight noted it, he did not reveal himself to see, as it did not seem violent and he surmised that the Master had merely been genuflecting.

Shortly thereafter the Master rose, genuflected once again, and left the room.

When the Knight came round the bed to check on His Majesty, the King seemed oddly pale. The Knight looked upon him closely and realised that his spirit had passed into the next world. After telling the account you have just read to his vassal outside the door, the Knight impaled himself on his sword and was found on the floor beside the King's bed, dead. May God have mercy upon us all.

--Cicero

Finding the world's rarest book in my library that Sunday afternoon was a bibliophile's dream. But now I'd give anything if I hadn't caught a glimpse of its hiding place behind my bookshelves. For while that outwardly charming volume fascinated and delighted the bibliomaniac world, it held dangerous secrets--secrets that not only ignited hostilities that had simmered for a millennium, but took from me everything I held most precious.

On that unforgettable afternoon I sat at my desk in the library, scrawling American addresses on ivory wedding invitation envelopes--hundreds of them. Sarah Townsend, my intended, had insisted my handwriting was infinitely preferable to that of the commercial calligraphers she knew. I wasn't sure I agreed, but anything for Sarah. A few hundred envelopes? Delighted, my love.

It was also infinitely preferable to the nasty task of home maintenance that awaited me outside. One of our ancient oaks, which had been ailing for several years, had keeled over against the house in a violent gale the previous week. It was still perched there, waiting to cause a new disaster. I'd intended to get to it that weekend, but . . .

The doorbell rang. I checked my watch as I rose and went to the door, stretching luxuriously. Four o'clock on a Sunday afternoon. The Sunday Times was still strewn about the sofa in pleasant disarray, its rumours of deepening hostilities between America and Iraq as remote as those faraway deserts. Even the lesser evil of a flu epidemic in London seemed remote, with the roses blooming and the birds singing outside the open French doors. Ah, but life was good here at the Orchard, long the family home of the Plumtree clan. The oak could wait. And it was time for tea.

I swung open the door, enjoying its characteristic creak on the old hinge.

"Max!" I exclaimed. "What a pleasant surprise. I was just going to put the kettle--"

"Sorry, Alex." My brother pushed past me, all business, into the hallway. "I need to borrow a book, if you don't mind. Sorry to disturb."

"Not at all," I murmured. I closed the front door and followed him into the library. I was used to Max's brief enthusiasms, his frequent small emergencies. I understood him well: He was simply a more concentrated version of myself. Emotionally, Max was more mercurial; physically, he was smaller and darker. He went straight to the shelf of reference books.

I watched him, as I leaned against my desk. "I've just been addressing the invitations for the Nantucket ceremony," I began to explain.

"Ah," he said distractedly, clearly not hearing a word I'd said. The vows I would take in little more than two months were not uppermost in his mind.

"I read in the paper this morning that aliens contacted the Queen. They spoke through her corgis at a polo match in Windsor Great Park."

"That's nice," he muttered, continuing to search through the richly stocked shelves--a bit wildly, it seemed to me. He was certainly in a flap about something.

"Not there," he said. "Damn! A client of mine--an anonymous one, funnily enough--said he'd already tried Maggs. They couldn't help him. So if I could, it'd be a coup. And I know we had that volume here . . . that heraldry volume Dad was forever showing us. I won't sell ours, of course, but at least my client could see it. And," Max said with exaggerated emphasis, quite pleased with himself, "if I have to meet with him, I can find out who he is. The book was a private issue, you know, a Dibdin Club edition. I have the impression he's after a more modern volume than the one we have, but I can't exactly remember the date of ours."

"Yes, I know the one you mean. It must be here somewhere." I went to a different wall of shelves to help him look; we had a very relaxed system of ordering our books, which allowed us the thrill of a treasure hunt each time we looked for an uncommon volume. And a Dibdin edition was a treasure . . . the Dibdin Club was the most prestigious group of bibliophiles in all England. Each year, one member chose an exceedingly rare volume from his or her own library and reissued it for the other members. It was a bit like a printing society, only less bourgeois and far more private. The Dibdin stopped just short of royalty, and its members held the loftiest titles--and books--in the land.

"Ah-ha!" Max cried, triumphantly snatching a large volume off the shelf.

"What's that?" I asked, squinting at the bookshelves. I went across to my brother, suddenly intrigued.

"Really, Alex!" Max rolled his eyes in exasperation. "I know you're busy with the wedding, my boy, but the world does carry on. I just told you it was the

Dibdin edition on heraldry, which I'd--"

"No, no, sorry. I mean what"--I bent down to reach to the back of the shelf--"is this?"

I knelt and lifted out several other books, placing them on the floor. Then I studied the wall behind the bookshelf more carefully. At this hour and season the sun was on the shelf directly; normally, I would have drawn the curtains by now to shield the spines from excessive light. "I do believe," I said, following a rectangular outline cut into the wood with my fingertips, "that there's something here."

I pushed on the rectangle, and it sprang outward toward me, opening on a hinge at its left edge. "I don't believe this," Max said incredulously, kneeling next to me and breathing down my neck. "Dad had another safe in the shelves?"

I wanted a torch; it was dark in the space, and I didn't fancy sticking my hand inside without knowing what was there. But I couldn't wait. I reached in and found that the area was quite small, perhaps twelve inches wide by eight deep. My fingers met with a hard object that felt very much like--why was I surprised?--a book. I pulled it out. Max and I found ourselves staring at a smallish volume, perhaps eight by six inches and half an inch thick.

"What are you doing here, then?" I said under my breath to the book.

Having something just short of an obsession with antiquarian books, I knew instantly that this was not any old volume. Its covers were upholstered with wine-red-velvet fabric. The covers and book itself were bound together with leather thongs; the binding of a very old book indeed--an incunable, in fact, a book from the cradle period of printing in the late fifteenth century. Book collectors positively salivated over such books, and often paid a great deal of money for them. Most were carefully preserved in museums.

Max and I exchanged a glance.

There was no title in the velvet on the front cover. I turned the book over and saw that the back cover was blank as well. The spine, too, was utterly devoid of print or decoration. Carefully, I lifted the cover to discover pristine, creamy-white rag paper. Rag, unlike modern woody stuff, held up miraculously well over the centuries without so much as discolouring.

"Good Lord," Max murmured as we stared down at the words on the page. "This is incredible. Look at that black letter--and you can see that they dampened the paper, which made a very deep impression. Alex, this is unquestionably an incunable."

"You're right. And look at the binding--definitely English. They've put the straps and clasps from the bottom up instead of the continental bottom down."

On the fine page before us, set in thick Gothic black-letter type, were the words:

DOMINUS SERVET VERITATEM ET VIRUM QUI EAM SCRIBIT

The remnants of my school Latin struggled to organise themselves into a translation. "God preserve the truth, and the man who writes--or prints?--it. . . . most unusual," I said.

"Mmm," Max replied. I knew he'd noticed, too, that there was no forematter, no early pages listing author, printer, or binder. Nor was there any date, though the heavy black-letter print and primitive printing process told us the book was likely to be fifteenth century. Just the rather dire Latin verse, followed by several blank pages.

Eagerly, I turned another page and found more black ink. The dark Gothic words opposed a breathtaking woodcut print of a knight in armour. A coat of arms ornamented the cloth covering his chain mail. He stood facing the reader, sword and shield in hand, features hidden by the metal helmet, and I noticed that a tiny four-poster was one of the symbols in the design on his chest. As best I could translate from Middle English the print opposite the woodcut of the knight, it said:

This is the story of the Royal Order of the Bedchamber, the loyal group of men who have pledged their lives to protect the King over the last three hundred years. We wish to tell the Order's history, and important historical facts known for centuries only to members of the Royal Order of the Bedchamber. These facts have never before been revealed, and were preserved by word of mouth within the Order until Giovanni Boccaccio became acquainted with a member of the Order, was captivated by the story, and wrote it down in 1371. We have printed it now thanks to the miracle of the printing press. We pray that no offence will be taken by His Majesty, King Edward IV, from our effort to record this magnificent truth.

So the book I held in my hands was an account of the daily activities of the knights of the Royal Order of the Bedchamber, evidently the king's closest and most loyal protectors. I'd never heard of them, but that didn't mean they couldn't have existed. I looked at Max. "Late fifteenth century, then, if the reigning monarch was Edward IV. But why would he take offence? It almost sounds as if the author expected the king to be displeased."

Max shrugged impatiently. "Let's have a look through the rest."

I turned through the remaining pages. The book contained only sixteen leaves; the last featured a stunningly detailed illustration, again from a woodcut, of a small four-poster surrounded by curtains. A knight knelt next to the bed dramatically, dripping dagger drawn at his side, a rampant lion with a crown in its teeth posturing aggressively on the coat of arms on his chest.

The pattern in the fabric of the bed curtains consisted of so many cross-hatchings that at first glance my eye imagined a multitude of nearly microscopic letters jumbled together and crossed by fine lines. When I looked more closely, I couldn't distinguish any letters at all. Holding the book a bit farther away, I blinked and looked again, trying to sort out the tiny patterns my eye perceived.

Not letters after all, I decided, but merely a design of overwhelming detail and precision, not to mention beauty. I turned back to the beginning to read the book's text. There was really very little print; a huge initial capital letter began the scant lines of text on each page.

It is the duty of each Knight of the Order to make the King safe, to guard his Bedchamber while he is sleeping, to taste his wine, water and mead before allowing him to drink. All Knights of the Order are sworn to give their lives before allowing any harm to come to His Majesty.

I turned another page.

For this reason the Knights of the Order are considered the bravest and most faithful of the realm. Because the King is appointed by God to reign over His people, the Knights serve God as well as the King. And so the tale I am about to relate is all the more tragic, because a Knight failed in his duty to both God and King.

The book went on for a bit here about the traditions of the Order, the specific duties of the knights and how they were carried out. I could hear Max breathing aloud as he too read. Then there came a fascinating bit about King Richard the Lion-Heart and the Crusades:

One of the most worrisome periods for the Knights of the Order was the Crusades. The Knights found themselves deeply suspicious of Saladin, the Sultan of Babylon with whom Richard established a firm friendship and even a truce in the Second Crusade. Every day the Knights expected the Saracen to commit some act of treachery toward their King, but this never came to pass. The unlikely friendship between the two rulers extended so far that King Richard offered his sister Joanna's hand in marriage to Saladin's brother, Al-Adil, as a peace offering. In the end, it was King Richard who grew tired of waiting for Saladin to deliver certain monies and the True Cross of Christ as agreed. It was our own King who broke the truce and slaughtered Saladin's people.

I read on, fascinated at this view of history through the knight's eyes. Several anecdotes later, I found a stunner:

Legend has held for hundreds of years that Richard the Lion-Heart died of a crossbow wound from a common poacher, after a disagreement with a peasant about some old coins the peasant had unearthed. This is not true; we wish the truth to be known. His Majesty lay abed for some time, recovering from his wound, which had unfortunately festered. As the noble Knight of the Order of the Bedchamber watched from behind the bed curtains one night, ever vigilant on behalf of his monarch, the Master of the Order crept in to the room.

Now, there was no reason for anyone to enter his Bedchamber at that hour unless they meant him harm. But the Master of the Order of the Bedchamber was much trusted and not a little feared, as it was known he had a violent temper, and his close relationship with His Majesty had never been doubted. True, his lands had been revoked with his title that spring over some perceived lack of loyalty, but the Master of the Order had seemed repentant for whatever had caused his penury and humiliation.

The Knight watched from behind the bed as the Master advanced and searched the Bedchamber for members of the Order such as himself. Seeing no one, and neglecting to look in the one spot the guarding Knight occupied, he proceeded to genuflect and kneel silently at the King's bedside.

Then, as the Knight guarded His Majesty silently from behind the curtain on the far side of the bed, he perceived that the Master of the Order made a subtle movement. While the Knight noted it, he did not reveal himself to see, as it did not seem violent and he surmised that the Master had merely been genuflecting.

Shortly thereafter the Master rose, genuflected once again, and left the room.

When the Knight came round the bed to check on His Majesty, the King seemed oddly pale. The Knight looked upon him closely and realised that his spirit had passed into the next world. After telling the account you have just read to his vassal outside the door, the Knight impaled himself on his sword and was found on the floor beside the King's bed, dead. May God have mercy upon us all.

Recenzii

"A treat for booklovers."

--Tales from a Red Herring

"As always, absorbing and enlightening."

--Rendezvous

--Tales from a Red Herring

"As always, absorbing and enlightening."

--Rendezvous