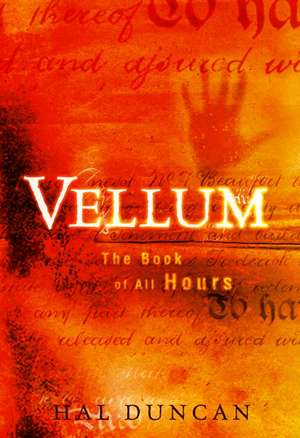

Vellum: The Book of All Hours

Autor Hal Duncanen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mar 2006

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

Spectrum Awards (2007), Locus Awards (2006)

VELLUM: THE BOOK OF ALL HOURS

It’s 2017 and angels and demons walk the earth. Once they were human; now they are unkin, transformed by the ancient machine-code language of reality itself. They seek The Book of All Hours, the mythical tome within which the blueprint for all reality is transcribed, which has been lost somewhere in the Vellum–the vast realm of eternity upon which our world is a mere scratch.

The Vellum, where the unkin are gathering for war.

The Vellum, where a fallen angel and a renegade devil are about to settle an age-old feud.

The Vellum, where the past, present, and future will collide with ancient worlds and myths.

And the Vellum will burn. . . .

Preț: 105.60 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 158

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.21€ • 20.83$ • 17.06£

20.21€ • 20.83$ • 17.06£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780345487315

ISBN-10: 0345487311

Pagini: 463

Dimensiuni: 162 x 230 x 27 mm

Greutate: 0.55 kg

Editura: Del Rey Books

Locul publicării:New York, NY

ISBN-10: 0345487311

Pagini: 463

Dimensiuni: 162 x 230 x 27 mm

Greutate: 0.55 kg

Editura: Del Rey Books

Locul publicării:New York, NY

Notă biografică

Born in 1971, Hal Duncan grew up in small-town Ayrshire, Scotland, and now lives in the West End of Glasgow. He is a member of the Glasgow SF Writers’ Circle and is currently working part-time as a computer programmer. Vellum is his first novel.

Extras

One - A Door Out of Reality

From the Great Beyond

From the Great Beyond she heard it, coming from the Deep Within. From the Great Beyond the goddess heard it, coming from the Deep Within. From the Great Beyond Inanna heard it, coming from the Deep Within.

She gave up heaven and earth, to journey down into the underworld, Inanna did, gave up her role as queen of heavens, holy priestess of the earth, to journey down into the underworld. In Uruk and in Badtibira, in Zabalam and Nippur, in Kish and in Akkad, she abandoned all her temples to descend into the Kur.

She gathered up the seven me into her hands, and with them in her hands, in her possession, she began her preparations.

Her lashes painted black with kohl, she laid the sugurra, crown of the steppe, upon her head, and fingered locks of fine, dark hair that fell across her forehead, touched them into place. She fastened tiny lapis beads around her neck and let a double strand of beads fall to her breast. Around her chest, she bound a golden breastplate that called quietly to men and youths, come to me, come, with warm, metallic grace. She slipped a golden bracelet over her soft hand, onto her slender wrist, and took a lapis rod and line in hand.

And finally, she furled her royal robe around her body.

Inanna set out for the Kur, her faithful servant, Lady Shubur, with her.

“Lady Shubur,” said Inanna, “my sukkal who gives wise consul, my steadfast support, the warrior who guards my flank, I am descending to the Kur, the underworld. If I do not return then sound a lamentation for me in the ruins. Pound the drum for me in the assemblies where the unkin gather and around the houses of the gods. Tear at your eyes, your mouth, your thighs. Wearing the beggar’s single robe of soiled sackcloth, then, go to the temple of the Lord Ilil in Nippur. Enter his sacred shrine and cry to him. Say these words:

“O father Lord Ilil, do not leave your daughter to death and damnation. Will you let your shining silver lie buried forever in the dust? Will you see your precious lapis shattered into shards of stone for the stoneworker, your aromatic cedar cut up into wood for the woodworker? Do not let the queen of heaven, holy priestess of the earth, be slaughtered in the Kur.

“If Lord Ilil will not assist you,” she said, “go to Ur, to the temple of Sin, and weep before my father. If he will not assist you, go to Eridu, to Enki’s temple, weep before the god of wisdom. Enki knows the food of life; he knows the water of life; he knows the secrets. I am sure he will not let me die.”

Thick with Trees and Thunderstorms

North Carolina, where the old 70 that runs from Hickory to Asheville cuts across the 225 running up from the south, from Spartanburg and beyond, up through the Blue Ridge Mountains and a land that’s thick with trees and thunderstorms. It’s on the map, but it’s a small town, or at least it looks it, hidden from the freeway, until you cut down past the sign that says Welcome to Marion, a Progressive Town, and gun your bike slow through the streets of the town center with its thrift stores and pharmacy, fire department, town hall, the odd music store or specialist shop that’s yet to lose its market to the Wal-Mart just a short drive down the road.

She rides past the calm, brick-fronted architecture that’s still somewhere in the 1950s, sleeping, waiting for a future that’s never going to happen, dreaming of a past that never really went away, out of the small town center and on to a commercial strip of fast-food restaurants and diners, a steak house and a Japanese, a derelict cinema sitting lonely in the middle of its own car park—all of these buildings just strung along the road like cheap plastic beads on a ragged necklace. She pulls off the road into a Hardee’s, switches off the engine and kicks down the bike-stand.

The burger tastes good—real meat in a thick, rough-shapen hunk, not some thin bland patty of processed gristle and fat—and she washes it down with deep sucking slurps of Mountain Dew, and twirls the straw in the cardboard bucket of a cup to rattle the ice as she looks out the window at the road, hot in the summer sun, humid and heavy. The sky is a brilliant blue, the blue of a Madonna’s robes, stretching up into forever, stretching—

—and she stands in front of the mirror in the washroom, leaning on the sink a second, dizzy with a sudden buzz, a hum, a song that ripples through her body like the air over a hot road shimmers in the sun. The Cant. Shit, she thinks. She must be getting close. She looks at the watch sitting up on top of the hand-dryer. The second hand flicks back and forth, random, sporadic, like one of those airplane instruments in a movie where the plane is going down in an electrical storm.

It’s August 4th, 2017. Sort of.

Steady again, she studies her eyes, black with mascara and with lack of sleep, and pushes her dark red hair back from her forehead. Even splashing more water on her face she still feels like a fucking zombie. Fucking zombie retro biker chick, she thinks. Beads in her hair, a beaded choker round her neck, a chicken-bone charm necklace over a gold circuit-patterned T-shirt. Shit, she looks like her fucking techno-hippy mother.

She picks up her watch and slips it over her wrist, reels out the earphones from the stick clipped to her belt and puts them in, clipping them into the booster sockets in her earrings so her lenses can pick up the video signals. The Sony VR5 logo flickers briefly across her vision as she shoulders her way out through the door, tapping at the datastick to switch it onto audio-only. She doesn’t need a heads-up weather forecast with ghost images of clouds or sunbursts, or a Routefinder sprite floating at every turnoff to point her this way or that. Not today.

She grabs her helmet from the handlebar of the bike and puts it on as she swings her leg up over the seat, flicks up the stand, zips up her leather biker jacket, kicks the engine into life.

The antique creature of steel and chrome growls between her legs, and another antique creature—one of leather and vinyl—screams in her ears.

“Looooooooooooooord!” howls Iggy Pop, and the murderous guitar of the Stooges’ TV Eye kicks in, as Phreedom Messenger opens up the throttle on the bike and roars out of her pit stop on the way to hell.

whore of babylon, queen of heaven

And Inanna continued on her way toward the underworld. She journeyed from ancient Sumer up the land between the rivers Tigris and Euphrates, through the whole of Babylon and into Hittite Haran. She traveled into Canaan with the Habiru who called her Ishtar. She went with them into Egypt and they called her Ashtaroth when she returned, leaving behind only a memory, the myth of Isis. She saw god-kings and city-states rise and fall, patriarchs murdered by sons who took their places and their names, armies and wars of territory and dominion. She traveled with the armies, with the whores and the musicians and the eunuch priests, offering solace in their tents, in tabernacles of sex and salvation. She had bastard sons by kings. She washed the feet of gods amongst men.

She saw villages burned and statues toppled. She saw kingdoms become federations, federations become empires. She saw whole dynasties of deities overthrown, their names and faces obliterated from the monuments they’d built, so, unlike them, she took new names, new faces. Times changed and she changed with them. She never accepted the new order that was tearing down the old around her, but she knew better than to fight it, watching the others stripped of honor, stripped of reverence, stripped of godhood, still calling themselves Sovereigns even as the Covenant shattered every idol in their temples. So she traveled as supplicant, as refugee, with mystery as her protector rather than force, cults rather than armies. She saw the seeds she dropped behind her take root in the earth and grow only to be crushed by military boots. She traveled with slaves and criminals.

She went from Israel, to Byzantium and Rome, this Queen of Heaven, Blessed Mother, full of grace, her new name and old titles echoing amongst the vaults of stone cathedrals, spaces as vast and hollow as the temples left long empty in Uruk and Badtibira, Zabalam and Nippur, Kish and Akkad.

She traveled in statues and pietàs, painted in indigo and gold in old Renaissance frescoes, Russian icons; traveled to the New World with conquistadors and missionaries, to plantations where the slaves danced round the fires at night, possessed by gods, by saints, by loas and orishas; journeyed across time to a New Age of carnival mythologies and stars worshipped in glossy parchments sold at newsstands, of rosaries and Tarot cards and television earth mothers fussing over the broken hearts and wounded prides of soft, spoiled inner children.

She journeyed on the road of no return, to the dark mansion of the god of death, the house where those who enter never leave, where those who enter lose all light, and feed on dust, clay for their bread. They see no sun; they dwell in night, clothed in black feathers of the carrion crow. Over the door and the bolt of the dark house, dust settles, moss and mildew grow.

She stopped, this Whore of Babylon, this Queen of Heaven. Inanna stopped before the entrance to the underworld, and turned to look back at her servant who had followed her down through the centuries, the millennia.

“Go now, Lady Shubur,” she said. “Do not forget my words.”

“My Queen,” says Lady Shubur.

“Go.”

A Sculpture of Time and Space

She shifts the engine to a lower gear, a lower growl, swings low and wide around the corners, slower as the bike climbs the steep, winding road into the mountains. White wooden churches stand with bible quotes lettered on hoardings at the side of the road, and shabby prefab houses perch in their little plots with leaning porches and pots of dying flowers in hanging baskets. They nestle in amongst the deep trees of bear and deer; this is hunting territory, a place of pickup trucks and men in armored vests with high-powered rifles and coolers filled with beer. Stars and Stripes on every house. On a dirt track coming off the road at her right-hand side a rustbucket of a car sits up on bricks, the legend #1 Dawg scrawled in paint across the battered panels of its side.

The bike swings left and right in wide curves round the tight corners and she leans down into them, following the flow, the rhythm of the constant turns and twists. The road snakes on right up into the hills and she snakes with it, like a cobra reared up ready to strike but swaying side to side, charmed by the music in its contours, switching gears, from growl to roar and back again. Slow and wide. Fast and tight. Left. Right. Left. Right. Sunlight flickers blinding white through the canopy of trees like the end of an old celluloid film rattling through a projector.

The road cuts deep into the sharp-carved shadows of tall trees for a second, slices between dark juts of moss-slicked rock and through a concrete underpass; and she takes the circling slip road off to the right and turns and turns, and then she’s up and out and on the Blue Ridge Parkway, riding the wide road that runs from mountain spine to mountain spine along the length of the whole range. And the sun is hot but the air is clear and crisp as a cool spring and she can look out to her left and to her right and see the world on either side, the hills in the beyond, the valleys in between, the vast, green, rough, soft sculpture of time and space, of earth and sky.

It’s places like this that you can’t tell where the world ends and the Vellum begins, she thinks. For all its asphalt artifice, for all the wooden mileage signposts scattered along its way, for all that you can look down into the valleys and still see the houses and churches, schools and factories of small towns cradled in the folds, up here reality, like the air, is thinner. The road is just a scratch on the skin of a god; if you came off it, she thinks, if you smashed straight through one of the low wooden fences and shot out into the air, you might crash right out of this world and into another, into a world empty of human life or filled with animal ghosts.

But those aren’t the kind of world she’s looking for, not by a long shot.

Inanna at the Gates of Hell

“Gatekeeper, open up your gate for me,” Inanna called. “If you refuse, I’ll smash this door, shatter the bolt, splinter the post. I’ll tear these doors down and raise up the dead to feast upon the living, until there are more dead souls walking in the world than are alive.”

Inanna stood before the outer gates of Kur, and she knocked loudly.

“Open the doors, you keeper of the gate,” she cried, her voice fierce. “Open up the doors, Neti! I come alone and ask for entry.”

“And who are you?” asked Neti, surly chief gatekeeper of the Kur.

“I am Inanna, Queen of Heavens, on my way into the West.”

“If you are really Queen of Heavens,” Neti said, “and on your way into the West, Inanna, why, why has your heart made you a traveler on the road of no return?”

“My sister, Eresh of the Greater Earth,” Inanna answered, “is the reason. I have come to see the funeral rites of Gugalanna, Bull of Heaven, her dead husband. I have come to see the rites, the funeral beer of his libations poured into the cup. Now open up.”

“Wait here, Inanna,” Neti said, “and I will give your message to my queen.”

And Neti, chief keeper of the gates of Kur, turned and entered the palace of Eresh, the Queen of the Underworld, of the Greater Earth.

Mary or Anna, Esther or Diana, Phreedom flicks through the many cards she carries in her wallet, all the identities she travels in. She picks one out almost at random—an Anna, this time—hands it to the clerk behind the counter. He smiles at her and she can’t help herself from thinking of the cheap motels she’s stayed in where the clerks are all sim sprites, electronic ghosts with just enough AI behind them to take care of check-ins and check-outs. Sim answerers are the cheaper option, now, than the old service sector wage slaves of the past; she’s kind of surprised that this place has a flesh receptionist. But maybe they just haven’t caught up with the times.

Another town, another Comfort Inn, she thinks. This time it’s Marion, but it could be anywhere. She watches as the clerk slashes the card through the machine and turns to watch the screen, waiting for confirmation. And she pauses, pen poised in her hand over the book, flicks her eyes up to the clock on the back wall and sees the second hand tick round, once, twice, then stop. The clerk is still, stopped in his stoop, one hand laid on the monitor, his drumming fingers caught between the beats. She flicks backward through the pages of the book, scanning the names for one that has a different look. She’s no idea what name he might have used here, but she knows she’ll know it when she sees it, by the little signs, not in the handwriting, in the snake of an s, the round mounds of an m, but in the imprints that it makes, not in the paper but in reality itself. The unkin can wear whatever names they want, whatever guises, but they still wear their nature in their attitude, in their actions. They leave traces.

And as it turns out, he hasn’t even bothered to use a false name.

Thomas Messenger.

It’s black ink on white paper but she sees it glowing white with a black aura, like its own afterimage. So her brother was here right enough.

She lets the second hand tick forward on the clock, and the clerk rises from his stoop, turns back to her.

“My queen,” said Neti, “a maid stands at the palace gates. She stands as firm as the foundations of a city wall, tall as the skies and wide as all the lands. She comes prepared, the seven me gathered into her hands. Her eyes are shadowed with dark kohl and in her hand she holds a lapis rod and line. Across her forehead fall her fine, dark locks of hair, arranged with care. She wears small lapis beads around her neck, a double strand of beads across her breast. Around her chest a breastplate calls, speaks to all men, says come, come to me. On her head she wears the sugurra, crown of the steppe, and there’s a golden bracelet on her wrist. My queen, she wears the royal robes wrapped round her body.”

And Phreedom swipes the keycard through the lock and opens the door into a room that’s just like every other room in this Comfort Inn, in every Comfort Inn, in every cheap hotel in every nowhere town in every state she’s been in. She dumps the helmet on the wooden dresser as the door clicks shut behind her, drapes the jacket on the back of a chair. She slips the chicken-bone necklace off over her head, unhooks the choker, slips the watch off of her wrist, and unclips the datastick at her hip, lays them all on the dark wood veneer. She peels the T-shirt off and lets it drop on top of the double bed’s thin fitted quilt of green and garish flowers, heads for the bathroom where—

The water from the shower head rains over her hand, hot patterings and trickling trails between her fingers. Her blue jeans lie crumpled on the floor but Phreedom has no memory of taking them off. Fuck, she thinks. Another cut. Another fold in time, a little nick in the Vellum. She’s on the threshold here.

She steps into the shower.

Broken Minutes and Bent Hours

“She is here, your sister Inanna, who carries the great whipping stick, the keppu toy, to stir the abzu up as Enki watches.”

When Eresh of the Greater Earth heard this, she slapped her thigh, bit at her bottom lip. When Eresh of the Greater Earth heard this, she raged.

“What have I done to anger her? I eat and drink with the Anunnaki, clay for my bread and stagnant water for my beer. What brings her here? I weep for young men and the sweethearts they’ve abandoned without choice. I weep for girls torn from their lover’s laps. I weep for children born before their time to die before they’ve lived.”

Her face turned scarlet as cut tamarisk, her lips as purple as a kuninu-vessel’s rim. She took the problem to her heart and brooded on it. After a while she spoke:

“Come, Neti, my chief keeper of the gates of Kur, and listen carefully to what I say: Lock up and bolt the seven gates of Kur, then, one by one, open each gate and let Inanna enter through the crack. Bring her down. But as she enters, take her regal costume from her, take the crown, the necklace and the beads that fall across her breast, the golden breastplate on her chest, the bracelet and the rod and line. Strip her of everything, even the royal robe, and let the holy priestess of the earth, the Queen of Heaven, enter here bowed low.”

Neti listened to his queen’s words, locked and bolted all the seven gates of Kur, the city of the dead. Then he opened the outer gate.

“Come, Inanna, enter,” Neti said to her, and as Inanna entered the first gate, the sugurra, crown of the steppe, was taken from her head.

“What is this?” asked Inanna.

“Quiet, Inanna,” she was told, “the customs of the city of the dead are perfect. They may not be questioned.”

And: Click. The door of Phreedom’s room swings slow upon its spring, snicks shut behind her as she steps out into the corridor, plastic magnetic keycard in her hand in her pocket.

Other unkin, she knows, have other methods for finding those who don’t want to be found. Some use the old ways: scrying in mirrors for a vision of their quarry on a corner, standing under a street sign; or sniffing out a psychic scent like bloodhounds, following it on foot across whole continents; or listening, head cocked, for the faintest echo of a unique sound, a voiceprint rippling across the atmosphere, half a world away. The Cant travels far.

Then there’s those who use absurd artifacts of their own invention, reinvention, mojo compasses and Geiger counters with their guts rewired to chitter randomly, palmtops with programs compiled into trinary, designed to print onscreen displays of names and assignations written into history before history even existed, the ancient me written in modern media. Some just find someone they think might know and rip an address straight out of their head. Phreedom’s no stranger to these methods.

“Where’s your brother, little girl?” he’d said.

“I don’t know.”

“We’ll see about that,” he’d said, his fingers curling round her throat.

No. Phreedom’s no stranger to these methods, but she works by something more like instinct, intuition. The unkin leave their traces in the times they travel through as much as in the spaces and the things, and Phreedom’s following a trail of broken minutes and bent hours that’s as . . . legible to her as Tom’s signature in the hotel guest book, even if it is a little . . . confused. In terms of time, her brother’s trail reads like some chain-gang fugitive crashing through bushes, crossing rivers, doubling back to cross again, stealing a car, exchanging clothes with a hobo and riding the railroad in a whole different direction—trying everything, anything, to get the bloodhounds off his trail. Phreedom knows that there’s some hounds you just can’t shake. She knows she has to find her brother before they do. Scratch that. She knows she has to find her brother before they did.

A Speck of Dirt Under a Fingernail

As she stepped through the second gate, the small lapis beads were taken from around her neck. And once again Inanna asked, “What is this?”

“Quiet, Inanna,” Neti told her. “The customs of the city of the dead are perfect. They may not be questioned.”

Click. The bar-handle of the door into the stairwell unlatches at the press of her hand, and she steps past the vending and ice machines on the landing, down the stairs toward the exit.

“I’ve found a way,” he says. “A sort of loophole, a door out of reality . . . In Ash—”

She cuts him off, fingers across his lips, and shakes her head.

They sit in the roadhouse—it’s about a year ago—sipping at their beers and looking across the booth at each other. Their bikes are parked outside and in a little while they’ll both go out, they’ll give each other one last hug before they kick the stands up, gun the engines and head off in different directions. She’s spent the last two years looking for him, praying that he doesn’t know what she does, that he isn’t like her, like Finnan. But she can see it in his eyes, like fear or fury. And he shows her his mark, on his chest, under his shirt, over his heart. Most people would just see smooth flesh, the beads and the mojo bag, the silver cross and dog tags. She sees his graving, his secret name written in light in the unkin script, like a luminous tattoo. He might as well have a halo, or horns.

“Don’t tell me,” she says. “It’s too dangerous if I know.”

And all she wants right now is for the world to be the way it was when they were kids, before the simple surface that they knew was stripped away and all the flesh and bones of its metaphysique shown underneath, the rippling sinews of paths twisted out of time and space, the tendons stretching between centuries, the white-bone structures of an eternity jointed, articulated, rebuilt by creatures that had stepped out of the mundane world long before either of them were even born. Creatures like they’d become, not even knowing it, and, in doing so, damned themselves to this insane existence. What do you do if the end of the world is coming and you’re an angel who doesn’t want to fight? Where do you go?

“The Vellum,” he says.

The Vellum. Like giving it a name makes it any more comprehensible, any more sane. A world under the world—or after it, or beyond it, inside, outside—those ideas don’t even fucking apply. Where’s the Vellum? Outside the mundane cosmos, as the ancients thought, further by far than they could possibly imagine in their measures of the heavens dwarfed by actualities of galaxies and clusters? Or buried in a speck of dirt under a fingernail? Where do the gods come from? Where do people go when they die? Where do angels travel in packs for fear of being slaughtered by their own shadows, huddle in fortress heavens against a void they need a fucking God of Gods to conquer? Phreedom’s seen a glimpse of it, just once, a plain of bird skulls stretching for as far as she can see, a vision given to her as a threat the day that she herself became one of these inhuman things. It was a warning given to a little girl who knew too much already, a message: this is what you’re getting yourself into. As desolate and vast as that vision might have been, she knows, it was only a tiny corner of the infinite Vellum.

She looks at him, her brother, Thomas. His eyes are brown flecked with green, as hers are green with flecks of brown; where his hair’s brown pushing for auburn, hers is rust red, streaked with ginger. They’re both autumn—if you listen to that kind of Eurotrash fashionazi shit on the webworlds—but where he’s kicking through the first fall leaves, she’s dancing round a Halloween bonfire.

“I’ll go into the Vellum,” Thomas says. “The Covenant won’t find me. Finnan—”

“Fuck Finnan,” she snarls. “If it wasn’t for that fucker, we’d have never . . .”

Never what? Never touched infinity? Never heard the Cant that resonates in every fiber of their fucking bodies? Never learned to hear that language, read the gravings of it in the world and in themselves, their own secret names? Never become unkin?

But she knows it isn’t true, that there was something in her that couldn’t help but be attracted to the crazy guy who lived in his castle of junk in the trailer park out in the middle of the desert where they came every winter, year after year, with their mom and dad, a snowbird family of the semi- nomadic Winnebago tribe. He didn’t hunt them out. He didn’t come to them and offer them eternity in the sand under their feet. They’d gone to him, first her brother then herself, because they just knew—in the way he touched the dry wind like a blind man feeling someone’s face, in the way he turned his head to watch vortices of cigarette smoke curl in the air—they knew he had some kind of way of reading the secrets hidden in the world around them. If it hadn’t been him who showed her—showed them both the world beneath the world, it would have been someone else, some other place, some other time.

But still, she can’t help hating him a little for the hell that hunts them both now, both her brother and herself. Or the heaven, rather.

Angels on Your Body

From her breast the double strand of beads were taken at the third gate.

“What is this?” Inanna asked, but, “Quiet, Inanna,” she was told again. “The ways of the underworld are perfect. They may not be questioned.”

Creak.

“Thanks.” The old guy smiles as he steps past her through the door she’s holding open and she nods “You’re welcome” and walks out into the car park.

“Angels on your body,” he calls after her, some misplaced Californian craziness of a blessing.

She swings her leg over the bike.

Most people have it wrong, she knows now. They think the unkin—wandering through their myths and legends, calling themselves gods here, angels there—they think these creatures rule eternity, own it as their realm. But eternity, the Vellum, is like . . . the media of reality itself, the blank page on which everything is written, on which anything could be written. The Vellum isn’t the absolute certainty of some city-state of Heaven; no, it’s the vast wilderness of uncertainty, possibility, the fucking primal chaos itself, and this angel empire of their dreams is just a colony of settlers trying to tame it, make it fit with their mad puritan ideals, a town of walls and fences, of warped zeal, of hatred and fear, holding out against the storms and the strange natives, and riding out with their cavalry and swords and guns to slaughter every painted savage and naked squaw who won’t accept their righteous laws of sin and purity. Angels and demons. Or the Covenant and the Sovereign Powers, as they like to call themselves. To the angels, even eternity itself is just another hell of redskin enemies to be purged and rebuilt, New Jerusalem . . . their New World. She wonders if they’ll have slave ships ferrying dead sinners to their Western Lands to toil in plantation purgatories.

For a second, looking across at her brother, in the roadhouse, she has a sudden image of him in a Civil War uniform, all the braiding torn from it and gray with dust so you can’t tell what side he’s on, or was on before he started running. She blinks and he’s normal again. That’s the thing about eternity. It gets fucking everywhen.

“They won’t find me,” he says.

“You won’t find him,” she screams, and she twists, snarling and cursing, sobbing, spitting blood and tears as one of the bastard fucking unkin pins her arms, wrenching them back behind her, cracking electric pain through dislocated shoulders, while the other gathers a fistful of her hair to snap her head back with one hand and, with the other, pound his fist into her face, into her jaw, again and again and again, till all that she can do is moan. I’ll kill you. I’ll fucking kill you, she’s thinking. I’ll fucking kill you all.

She can feel his mind touching on hers, a whisper inside her head, “Where is he?” The cigarette still burns in the ashtray on the Formica tabletop of Finnan’s long-abandoned trailer. She shouldn’t have come back here. The smoke curls upward, languid; the cigarette itself is mostly ash now.

He turns to look at the table, then peers into her face.

“Ash?” he says. “What are you thinking, little girl?”

She looks at the cigarette, stares at the cigarette, the ash, that ash, not any other, not the spoken syllable of an interrupted word. She’s not giving these fuckers anything.

“Fuck you,” she says, and he punches her again.

“We’ll find him,” the one holding her arms is saying in her ear. “You can make it easy for us, easy for yourself, but either way we’ll still find him. Please.”

Good cop, bad cop. Carter and Pechorin, they introduced themselves as. Golden Boy and Count Dracula, she thought with a sneer, dismissing them until they took off their shades and she saw just how empty their eyes were.

Fuck you. Fuck you, she thinks. I’ll fucking kill you. And you won’t find him.

The punching stops. She can’t see anything anymore, for the blood and the blinding buzz saw sparks of pain, but she can feel him pawing at her now, pulling at her jeans, ripping her T-shirt. It’s six months since she last saw her brother, but the scent of memory is strong on her; it’s what led them to her in their hunt for him. They’re gearing up for the apocalypse. Most of the unkin are already signed to one side or the other, and it’s only the odd new blood, born in a backwater, living on the move, who’ve managed to evade the gatherers. For all she knows its only her and Finnan and her brother that are still free. And she’s not even sure about herself.

I’ll fucking kill you all.

She can feel his hand pushing inside her jeans; she’s falling into herself, the only escape from the brutality of angels. He starts to grunt, his fingers pushing, probing.

You won’t find him.

But I will.

Hunter Seeker

When she entered the fourth gate, the breastplate was stripped from her chest.

“What is this?” asked Inanna.

“Quiet, Inanna,” she was told, “the customs of the city of the dead are perfect. They may not be questioned.”

Doom. She catches a glimpse of past or future, an echo across reality, across the present . . . across the road: a car door thudding shut as two men in black suits stand, arms folded, bug-eyed in black shades, beckoning to the person standing where she is now, to her brother Thomas. It’s superimposed over her view just like a sim world in her lenses would be, but she knows this is no electronic apparition. She knows those fuckers; her personal demons, they are, those angels of death, hired gods. Fucking unkin. She can spot them a mile off. She can spot them a month off.

The vision only lasts a second, but it’s enough to follow.

From the Great Beyond

From the Great Beyond she heard it, coming from the Deep Within. From the Great Beyond the goddess heard it, coming from the Deep Within. From the Great Beyond Inanna heard it, coming from the Deep Within.

She gave up heaven and earth, to journey down into the underworld, Inanna did, gave up her role as queen of heavens, holy priestess of the earth, to journey down into the underworld. In Uruk and in Badtibira, in Zabalam and Nippur, in Kish and in Akkad, she abandoned all her temples to descend into the Kur.

She gathered up the seven me into her hands, and with them in her hands, in her possession, she began her preparations.

Her lashes painted black with kohl, she laid the sugurra, crown of the steppe, upon her head, and fingered locks of fine, dark hair that fell across her forehead, touched them into place. She fastened tiny lapis beads around her neck and let a double strand of beads fall to her breast. Around her chest, she bound a golden breastplate that called quietly to men and youths, come to me, come, with warm, metallic grace. She slipped a golden bracelet over her soft hand, onto her slender wrist, and took a lapis rod and line in hand.

And finally, she furled her royal robe around her body.

Inanna set out for the Kur, her faithful servant, Lady Shubur, with her.

“Lady Shubur,” said Inanna, “my sukkal who gives wise consul, my steadfast support, the warrior who guards my flank, I am descending to the Kur, the underworld. If I do not return then sound a lamentation for me in the ruins. Pound the drum for me in the assemblies where the unkin gather and around the houses of the gods. Tear at your eyes, your mouth, your thighs. Wearing the beggar’s single robe of soiled sackcloth, then, go to the temple of the Lord Ilil in Nippur. Enter his sacred shrine and cry to him. Say these words:

“O father Lord Ilil, do not leave your daughter to death and damnation. Will you let your shining silver lie buried forever in the dust? Will you see your precious lapis shattered into shards of stone for the stoneworker, your aromatic cedar cut up into wood for the woodworker? Do not let the queen of heaven, holy priestess of the earth, be slaughtered in the Kur.

“If Lord Ilil will not assist you,” she said, “go to Ur, to the temple of Sin, and weep before my father. If he will not assist you, go to Eridu, to Enki’s temple, weep before the god of wisdom. Enki knows the food of life; he knows the water of life; he knows the secrets. I am sure he will not let me die.”

Thick with Trees and Thunderstorms

North Carolina, where the old 70 that runs from Hickory to Asheville cuts across the 225 running up from the south, from Spartanburg and beyond, up through the Blue Ridge Mountains and a land that’s thick with trees and thunderstorms. It’s on the map, but it’s a small town, or at least it looks it, hidden from the freeway, until you cut down past the sign that says Welcome to Marion, a Progressive Town, and gun your bike slow through the streets of the town center with its thrift stores and pharmacy, fire department, town hall, the odd music store or specialist shop that’s yet to lose its market to the Wal-Mart just a short drive down the road.

She rides past the calm, brick-fronted architecture that’s still somewhere in the 1950s, sleeping, waiting for a future that’s never going to happen, dreaming of a past that never really went away, out of the small town center and on to a commercial strip of fast-food restaurants and diners, a steak house and a Japanese, a derelict cinema sitting lonely in the middle of its own car park—all of these buildings just strung along the road like cheap plastic beads on a ragged necklace. She pulls off the road into a Hardee’s, switches off the engine and kicks down the bike-stand.

The burger tastes good—real meat in a thick, rough-shapen hunk, not some thin bland patty of processed gristle and fat—and she washes it down with deep sucking slurps of Mountain Dew, and twirls the straw in the cardboard bucket of a cup to rattle the ice as she looks out the window at the road, hot in the summer sun, humid and heavy. The sky is a brilliant blue, the blue of a Madonna’s robes, stretching up into forever, stretching—

—and she stands in front of the mirror in the washroom, leaning on the sink a second, dizzy with a sudden buzz, a hum, a song that ripples through her body like the air over a hot road shimmers in the sun. The Cant. Shit, she thinks. She must be getting close. She looks at the watch sitting up on top of the hand-dryer. The second hand flicks back and forth, random, sporadic, like one of those airplane instruments in a movie where the plane is going down in an electrical storm.

It’s August 4th, 2017. Sort of.

Steady again, she studies her eyes, black with mascara and with lack of sleep, and pushes her dark red hair back from her forehead. Even splashing more water on her face she still feels like a fucking zombie. Fucking zombie retro biker chick, she thinks. Beads in her hair, a beaded choker round her neck, a chicken-bone charm necklace over a gold circuit-patterned T-shirt. Shit, she looks like her fucking techno-hippy mother.

She picks up her watch and slips it over her wrist, reels out the earphones from the stick clipped to her belt and puts them in, clipping them into the booster sockets in her earrings so her lenses can pick up the video signals. The Sony VR5 logo flickers briefly across her vision as she shoulders her way out through the door, tapping at the datastick to switch it onto audio-only. She doesn’t need a heads-up weather forecast with ghost images of clouds or sunbursts, or a Routefinder sprite floating at every turnoff to point her this way or that. Not today.

She grabs her helmet from the handlebar of the bike and puts it on as she swings her leg up over the seat, flicks up the stand, zips up her leather biker jacket, kicks the engine into life.

The antique creature of steel and chrome growls between her legs, and another antique creature—one of leather and vinyl—screams in her ears.

“Looooooooooooooord!” howls Iggy Pop, and the murderous guitar of the Stooges’ TV Eye kicks in, as Phreedom Messenger opens up the throttle on the bike and roars out of her pit stop on the way to hell.

whore of babylon, queen of heaven

And Inanna continued on her way toward the underworld. She journeyed from ancient Sumer up the land between the rivers Tigris and Euphrates, through the whole of Babylon and into Hittite Haran. She traveled into Canaan with the Habiru who called her Ishtar. She went with them into Egypt and they called her Ashtaroth when she returned, leaving behind only a memory, the myth of Isis. She saw god-kings and city-states rise and fall, patriarchs murdered by sons who took their places and their names, armies and wars of territory and dominion. She traveled with the armies, with the whores and the musicians and the eunuch priests, offering solace in their tents, in tabernacles of sex and salvation. She had bastard sons by kings. She washed the feet of gods amongst men.

She saw villages burned and statues toppled. She saw kingdoms become federations, federations become empires. She saw whole dynasties of deities overthrown, their names and faces obliterated from the monuments they’d built, so, unlike them, she took new names, new faces. Times changed and she changed with them. She never accepted the new order that was tearing down the old around her, but she knew better than to fight it, watching the others stripped of honor, stripped of reverence, stripped of godhood, still calling themselves Sovereigns even as the Covenant shattered every idol in their temples. So she traveled as supplicant, as refugee, with mystery as her protector rather than force, cults rather than armies. She saw the seeds she dropped behind her take root in the earth and grow only to be crushed by military boots. She traveled with slaves and criminals.

She went from Israel, to Byzantium and Rome, this Queen of Heaven, Blessed Mother, full of grace, her new name and old titles echoing amongst the vaults of stone cathedrals, spaces as vast and hollow as the temples left long empty in Uruk and Badtibira, Zabalam and Nippur, Kish and Akkad.

She traveled in statues and pietàs, painted in indigo and gold in old Renaissance frescoes, Russian icons; traveled to the New World with conquistadors and missionaries, to plantations where the slaves danced round the fires at night, possessed by gods, by saints, by loas and orishas; journeyed across time to a New Age of carnival mythologies and stars worshipped in glossy parchments sold at newsstands, of rosaries and Tarot cards and television earth mothers fussing over the broken hearts and wounded prides of soft, spoiled inner children.

She journeyed on the road of no return, to the dark mansion of the god of death, the house where those who enter never leave, where those who enter lose all light, and feed on dust, clay for their bread. They see no sun; they dwell in night, clothed in black feathers of the carrion crow. Over the door and the bolt of the dark house, dust settles, moss and mildew grow.

She stopped, this Whore of Babylon, this Queen of Heaven. Inanna stopped before the entrance to the underworld, and turned to look back at her servant who had followed her down through the centuries, the millennia.

“Go now, Lady Shubur,” she said. “Do not forget my words.”

“My Queen,” says Lady Shubur.

“Go.”

A Sculpture of Time and Space

She shifts the engine to a lower gear, a lower growl, swings low and wide around the corners, slower as the bike climbs the steep, winding road into the mountains. White wooden churches stand with bible quotes lettered on hoardings at the side of the road, and shabby prefab houses perch in their little plots with leaning porches and pots of dying flowers in hanging baskets. They nestle in amongst the deep trees of bear and deer; this is hunting territory, a place of pickup trucks and men in armored vests with high-powered rifles and coolers filled with beer. Stars and Stripes on every house. On a dirt track coming off the road at her right-hand side a rustbucket of a car sits up on bricks, the legend #1 Dawg scrawled in paint across the battered panels of its side.

The bike swings left and right in wide curves round the tight corners and she leans down into them, following the flow, the rhythm of the constant turns and twists. The road snakes on right up into the hills and she snakes with it, like a cobra reared up ready to strike but swaying side to side, charmed by the music in its contours, switching gears, from growl to roar and back again. Slow and wide. Fast and tight. Left. Right. Left. Right. Sunlight flickers blinding white through the canopy of trees like the end of an old celluloid film rattling through a projector.

The road cuts deep into the sharp-carved shadows of tall trees for a second, slices between dark juts of moss-slicked rock and through a concrete underpass; and she takes the circling slip road off to the right and turns and turns, and then she’s up and out and on the Blue Ridge Parkway, riding the wide road that runs from mountain spine to mountain spine along the length of the whole range. And the sun is hot but the air is clear and crisp as a cool spring and she can look out to her left and to her right and see the world on either side, the hills in the beyond, the valleys in between, the vast, green, rough, soft sculpture of time and space, of earth and sky.

It’s places like this that you can’t tell where the world ends and the Vellum begins, she thinks. For all its asphalt artifice, for all the wooden mileage signposts scattered along its way, for all that you can look down into the valleys and still see the houses and churches, schools and factories of small towns cradled in the folds, up here reality, like the air, is thinner. The road is just a scratch on the skin of a god; if you came off it, she thinks, if you smashed straight through one of the low wooden fences and shot out into the air, you might crash right out of this world and into another, into a world empty of human life or filled with animal ghosts.

But those aren’t the kind of world she’s looking for, not by a long shot.

Inanna at the Gates of Hell

“Gatekeeper, open up your gate for me,” Inanna called. “If you refuse, I’ll smash this door, shatter the bolt, splinter the post. I’ll tear these doors down and raise up the dead to feast upon the living, until there are more dead souls walking in the world than are alive.”

Inanna stood before the outer gates of Kur, and she knocked loudly.

“Open the doors, you keeper of the gate,” she cried, her voice fierce. “Open up the doors, Neti! I come alone and ask for entry.”

“And who are you?” asked Neti, surly chief gatekeeper of the Kur.

“I am Inanna, Queen of Heavens, on my way into the West.”

“If you are really Queen of Heavens,” Neti said, “and on your way into the West, Inanna, why, why has your heart made you a traveler on the road of no return?”

“My sister, Eresh of the Greater Earth,” Inanna answered, “is the reason. I have come to see the funeral rites of Gugalanna, Bull of Heaven, her dead husband. I have come to see the rites, the funeral beer of his libations poured into the cup. Now open up.”

“Wait here, Inanna,” Neti said, “and I will give your message to my queen.”

And Neti, chief keeper of the gates of Kur, turned and entered the palace of Eresh, the Queen of the Underworld, of the Greater Earth.

Mary or Anna, Esther or Diana, Phreedom flicks through the many cards she carries in her wallet, all the identities she travels in. She picks one out almost at random—an Anna, this time—hands it to the clerk behind the counter. He smiles at her and she can’t help herself from thinking of the cheap motels she’s stayed in where the clerks are all sim sprites, electronic ghosts with just enough AI behind them to take care of check-ins and check-outs. Sim answerers are the cheaper option, now, than the old service sector wage slaves of the past; she’s kind of surprised that this place has a flesh receptionist. But maybe they just haven’t caught up with the times.

Another town, another Comfort Inn, she thinks. This time it’s Marion, but it could be anywhere. She watches as the clerk slashes the card through the machine and turns to watch the screen, waiting for confirmation. And she pauses, pen poised in her hand over the book, flicks her eyes up to the clock on the back wall and sees the second hand tick round, once, twice, then stop. The clerk is still, stopped in his stoop, one hand laid on the monitor, his drumming fingers caught between the beats. She flicks backward through the pages of the book, scanning the names for one that has a different look. She’s no idea what name he might have used here, but she knows she’ll know it when she sees it, by the little signs, not in the handwriting, in the snake of an s, the round mounds of an m, but in the imprints that it makes, not in the paper but in reality itself. The unkin can wear whatever names they want, whatever guises, but they still wear their nature in their attitude, in their actions. They leave traces.

And as it turns out, he hasn’t even bothered to use a false name.

Thomas Messenger.

It’s black ink on white paper but she sees it glowing white with a black aura, like its own afterimage. So her brother was here right enough.

She lets the second hand tick forward on the clock, and the clerk rises from his stoop, turns back to her.

“My queen,” said Neti, “a maid stands at the palace gates. She stands as firm as the foundations of a city wall, tall as the skies and wide as all the lands. She comes prepared, the seven me gathered into her hands. Her eyes are shadowed with dark kohl and in her hand she holds a lapis rod and line. Across her forehead fall her fine, dark locks of hair, arranged with care. She wears small lapis beads around her neck, a double strand of beads across her breast. Around her chest a breastplate calls, speaks to all men, says come, come to me. On her head she wears the sugurra, crown of the steppe, and there’s a golden bracelet on her wrist. My queen, she wears the royal robes wrapped round her body.”

And Phreedom swipes the keycard through the lock and opens the door into a room that’s just like every other room in this Comfort Inn, in every Comfort Inn, in every cheap hotel in every nowhere town in every state she’s been in. She dumps the helmet on the wooden dresser as the door clicks shut behind her, drapes the jacket on the back of a chair. She slips the chicken-bone necklace off over her head, unhooks the choker, slips the watch off of her wrist, and unclips the datastick at her hip, lays them all on the dark wood veneer. She peels the T-shirt off and lets it drop on top of the double bed’s thin fitted quilt of green and garish flowers, heads for the bathroom where—

The water from the shower head rains over her hand, hot patterings and trickling trails between her fingers. Her blue jeans lie crumpled on the floor but Phreedom has no memory of taking them off. Fuck, she thinks. Another cut. Another fold in time, a little nick in the Vellum. She’s on the threshold here.

She steps into the shower.

Broken Minutes and Bent Hours

“She is here, your sister Inanna, who carries the great whipping stick, the keppu toy, to stir the abzu up as Enki watches.”

When Eresh of the Greater Earth heard this, she slapped her thigh, bit at her bottom lip. When Eresh of the Greater Earth heard this, she raged.

“What have I done to anger her? I eat and drink with the Anunnaki, clay for my bread and stagnant water for my beer. What brings her here? I weep for young men and the sweethearts they’ve abandoned without choice. I weep for girls torn from their lover’s laps. I weep for children born before their time to die before they’ve lived.”

Her face turned scarlet as cut tamarisk, her lips as purple as a kuninu-vessel’s rim. She took the problem to her heart and brooded on it. After a while she spoke:

“Come, Neti, my chief keeper of the gates of Kur, and listen carefully to what I say: Lock up and bolt the seven gates of Kur, then, one by one, open each gate and let Inanna enter through the crack. Bring her down. But as she enters, take her regal costume from her, take the crown, the necklace and the beads that fall across her breast, the golden breastplate on her chest, the bracelet and the rod and line. Strip her of everything, even the royal robe, and let the holy priestess of the earth, the Queen of Heaven, enter here bowed low.”

Neti listened to his queen’s words, locked and bolted all the seven gates of Kur, the city of the dead. Then he opened the outer gate.

“Come, Inanna, enter,” Neti said to her, and as Inanna entered the first gate, the sugurra, crown of the steppe, was taken from her head.

“What is this?” asked Inanna.

“Quiet, Inanna,” she was told, “the customs of the city of the dead are perfect. They may not be questioned.”

And: Click. The door of Phreedom’s room swings slow upon its spring, snicks shut behind her as she steps out into the corridor, plastic magnetic keycard in her hand in her pocket.

Other unkin, she knows, have other methods for finding those who don’t want to be found. Some use the old ways: scrying in mirrors for a vision of their quarry on a corner, standing under a street sign; or sniffing out a psychic scent like bloodhounds, following it on foot across whole continents; or listening, head cocked, for the faintest echo of a unique sound, a voiceprint rippling across the atmosphere, half a world away. The Cant travels far.

Then there’s those who use absurd artifacts of their own invention, reinvention, mojo compasses and Geiger counters with their guts rewired to chitter randomly, palmtops with programs compiled into trinary, designed to print onscreen displays of names and assignations written into history before history even existed, the ancient me written in modern media. Some just find someone they think might know and rip an address straight out of their head. Phreedom’s no stranger to these methods.

“Where’s your brother, little girl?” he’d said.

“I don’t know.”

“We’ll see about that,” he’d said, his fingers curling round her throat.

No. Phreedom’s no stranger to these methods, but she works by something more like instinct, intuition. The unkin leave their traces in the times they travel through as much as in the spaces and the things, and Phreedom’s following a trail of broken minutes and bent hours that’s as . . . legible to her as Tom’s signature in the hotel guest book, even if it is a little . . . confused. In terms of time, her brother’s trail reads like some chain-gang fugitive crashing through bushes, crossing rivers, doubling back to cross again, stealing a car, exchanging clothes with a hobo and riding the railroad in a whole different direction—trying everything, anything, to get the bloodhounds off his trail. Phreedom knows that there’s some hounds you just can’t shake. She knows she has to find her brother before they do. Scratch that. She knows she has to find her brother before they did.

A Speck of Dirt Under a Fingernail

As she stepped through the second gate, the small lapis beads were taken from around her neck. And once again Inanna asked, “What is this?”

“Quiet, Inanna,” Neti told her. “The customs of the city of the dead are perfect. They may not be questioned.”

Click. The bar-handle of the door into the stairwell unlatches at the press of her hand, and she steps past the vending and ice machines on the landing, down the stairs toward the exit.

“I’ve found a way,” he says. “A sort of loophole, a door out of reality . . . In Ash—”

She cuts him off, fingers across his lips, and shakes her head.

They sit in the roadhouse—it’s about a year ago—sipping at their beers and looking across the booth at each other. Their bikes are parked outside and in a little while they’ll both go out, they’ll give each other one last hug before they kick the stands up, gun the engines and head off in different directions. She’s spent the last two years looking for him, praying that he doesn’t know what she does, that he isn’t like her, like Finnan. But she can see it in his eyes, like fear or fury. And he shows her his mark, on his chest, under his shirt, over his heart. Most people would just see smooth flesh, the beads and the mojo bag, the silver cross and dog tags. She sees his graving, his secret name written in light in the unkin script, like a luminous tattoo. He might as well have a halo, or horns.

“Don’t tell me,” she says. “It’s too dangerous if I know.”

And all she wants right now is for the world to be the way it was when they were kids, before the simple surface that they knew was stripped away and all the flesh and bones of its metaphysique shown underneath, the rippling sinews of paths twisted out of time and space, the tendons stretching between centuries, the white-bone structures of an eternity jointed, articulated, rebuilt by creatures that had stepped out of the mundane world long before either of them were even born. Creatures like they’d become, not even knowing it, and, in doing so, damned themselves to this insane existence. What do you do if the end of the world is coming and you’re an angel who doesn’t want to fight? Where do you go?

“The Vellum,” he says.

The Vellum. Like giving it a name makes it any more comprehensible, any more sane. A world under the world—or after it, or beyond it, inside, outside—those ideas don’t even fucking apply. Where’s the Vellum? Outside the mundane cosmos, as the ancients thought, further by far than they could possibly imagine in their measures of the heavens dwarfed by actualities of galaxies and clusters? Or buried in a speck of dirt under a fingernail? Where do the gods come from? Where do people go when they die? Where do angels travel in packs for fear of being slaughtered by their own shadows, huddle in fortress heavens against a void they need a fucking God of Gods to conquer? Phreedom’s seen a glimpse of it, just once, a plain of bird skulls stretching for as far as she can see, a vision given to her as a threat the day that she herself became one of these inhuman things. It was a warning given to a little girl who knew too much already, a message: this is what you’re getting yourself into. As desolate and vast as that vision might have been, she knows, it was only a tiny corner of the infinite Vellum.

She looks at him, her brother, Thomas. His eyes are brown flecked with green, as hers are green with flecks of brown; where his hair’s brown pushing for auburn, hers is rust red, streaked with ginger. They’re both autumn—if you listen to that kind of Eurotrash fashionazi shit on the webworlds—but where he’s kicking through the first fall leaves, she’s dancing round a Halloween bonfire.

“I’ll go into the Vellum,” Thomas says. “The Covenant won’t find me. Finnan—”

“Fuck Finnan,” she snarls. “If it wasn’t for that fucker, we’d have never . . .”

Never what? Never touched infinity? Never heard the Cant that resonates in every fiber of their fucking bodies? Never learned to hear that language, read the gravings of it in the world and in themselves, their own secret names? Never become unkin?

But she knows it isn’t true, that there was something in her that couldn’t help but be attracted to the crazy guy who lived in his castle of junk in the trailer park out in the middle of the desert where they came every winter, year after year, with their mom and dad, a snowbird family of the semi- nomadic Winnebago tribe. He didn’t hunt them out. He didn’t come to them and offer them eternity in the sand under their feet. They’d gone to him, first her brother then herself, because they just knew—in the way he touched the dry wind like a blind man feeling someone’s face, in the way he turned his head to watch vortices of cigarette smoke curl in the air—they knew he had some kind of way of reading the secrets hidden in the world around them. If it hadn’t been him who showed her—showed them both the world beneath the world, it would have been someone else, some other place, some other time.

But still, she can’t help hating him a little for the hell that hunts them both now, both her brother and herself. Or the heaven, rather.

Angels on Your Body

From her breast the double strand of beads were taken at the third gate.

“What is this?” Inanna asked, but, “Quiet, Inanna,” she was told again. “The ways of the underworld are perfect. They may not be questioned.”

Creak.

“Thanks.” The old guy smiles as he steps past her through the door she’s holding open and she nods “You’re welcome” and walks out into the car park.

“Angels on your body,” he calls after her, some misplaced Californian craziness of a blessing.

She swings her leg over the bike.

Most people have it wrong, she knows now. They think the unkin—wandering through their myths and legends, calling themselves gods here, angels there—they think these creatures rule eternity, own it as their realm. But eternity, the Vellum, is like . . . the media of reality itself, the blank page on which everything is written, on which anything could be written. The Vellum isn’t the absolute certainty of some city-state of Heaven; no, it’s the vast wilderness of uncertainty, possibility, the fucking primal chaos itself, and this angel empire of their dreams is just a colony of settlers trying to tame it, make it fit with their mad puritan ideals, a town of walls and fences, of warped zeal, of hatred and fear, holding out against the storms and the strange natives, and riding out with their cavalry and swords and guns to slaughter every painted savage and naked squaw who won’t accept their righteous laws of sin and purity. Angels and demons. Or the Covenant and the Sovereign Powers, as they like to call themselves. To the angels, even eternity itself is just another hell of redskin enemies to be purged and rebuilt, New Jerusalem . . . their New World. She wonders if they’ll have slave ships ferrying dead sinners to their Western Lands to toil in plantation purgatories.

For a second, looking across at her brother, in the roadhouse, she has a sudden image of him in a Civil War uniform, all the braiding torn from it and gray with dust so you can’t tell what side he’s on, or was on before he started running. She blinks and he’s normal again. That’s the thing about eternity. It gets fucking everywhen.

“They won’t find me,” he says.

“You won’t find him,” she screams, and she twists, snarling and cursing, sobbing, spitting blood and tears as one of the bastard fucking unkin pins her arms, wrenching them back behind her, cracking electric pain through dislocated shoulders, while the other gathers a fistful of her hair to snap her head back with one hand and, with the other, pound his fist into her face, into her jaw, again and again and again, till all that she can do is moan. I’ll kill you. I’ll fucking kill you, she’s thinking. I’ll fucking kill you all.

She can feel his mind touching on hers, a whisper inside her head, “Where is he?” The cigarette still burns in the ashtray on the Formica tabletop of Finnan’s long-abandoned trailer. She shouldn’t have come back here. The smoke curls upward, languid; the cigarette itself is mostly ash now.

He turns to look at the table, then peers into her face.

“Ash?” he says. “What are you thinking, little girl?”

She looks at the cigarette, stares at the cigarette, the ash, that ash, not any other, not the spoken syllable of an interrupted word. She’s not giving these fuckers anything.

“Fuck you,” she says, and he punches her again.

“We’ll find him,” the one holding her arms is saying in her ear. “You can make it easy for us, easy for yourself, but either way we’ll still find him. Please.”

Good cop, bad cop. Carter and Pechorin, they introduced themselves as. Golden Boy and Count Dracula, she thought with a sneer, dismissing them until they took off their shades and she saw just how empty their eyes were.

Fuck you. Fuck you, she thinks. I’ll fucking kill you. And you won’t find him.

The punching stops. She can’t see anything anymore, for the blood and the blinding buzz saw sparks of pain, but she can feel him pawing at her now, pulling at her jeans, ripping her T-shirt. It’s six months since she last saw her brother, but the scent of memory is strong on her; it’s what led them to her in their hunt for him. They’re gearing up for the apocalypse. Most of the unkin are already signed to one side or the other, and it’s only the odd new blood, born in a backwater, living on the move, who’ve managed to evade the gatherers. For all she knows its only her and Finnan and her brother that are still free. And she’s not even sure about herself.

I’ll fucking kill you all.

She can feel his hand pushing inside her jeans; she’s falling into herself, the only escape from the brutality of angels. He starts to grunt, his fingers pushing, probing.

You won’t find him.

But I will.

Hunter Seeker

When she entered the fourth gate, the breastplate was stripped from her chest.

“What is this?” asked Inanna.

“Quiet, Inanna,” she was told, “the customs of the city of the dead are perfect. They may not be questioned.”

Doom. She catches a glimpse of past or future, an echo across reality, across the present . . . across the road: a car door thudding shut as two men in black suits stand, arms folded, bug-eyed in black shades, beckoning to the person standing where she is now, to her brother Thomas. It’s superimposed over her view just like a sim world in her lenses would be, but she knows this is no electronic apparition. She knows those fuckers; her personal demons, they are, those angels of death, hired gods. Fucking unkin. She can spot them a mile off. She can spot them a month off.

The vision only lasts a second, but it’s enough to follow.

Recenzii

“In Vellum–a monstrously brilliant and often hilarious novel of mad Irishmen, bad angels, femmes fatales, and demons–we are presented with the tale of a war occurring throughout the breadth and depth of time and space. Hal Duncan has, at the very least, created the Guernica of science fiction.”

–Lucius Shepard, author of A Handbook of American Prayer

“A mind-blowing read that’s genuinely unlike anything you’ve ever read before . . . Vellum has expanded fantasy’s limits like nothing published in years.”

–SFX (five-star “must-read” review)

“Duncan’s writing is fluent and powerful. He possesses an imagination capable of both conjuring worlds and capturing the intricacies of moments. Vellum is more than a novel; it’s a vision.”

–Jeffrey Ford, author of The Girl in the Glass

“A remarkably ambitious debut novel. For lovers of innovative fantasy, it’s a must-read.”

–Interzone

“Vellum is a revelation–the opening gambit in the career of a mind-blowing colossal talent whose impact will be felt for decades.”

–Jeff VanderMeer, author of City of Saints and Madmen

–Lucius Shepard, author of A Handbook of American Prayer

“A mind-blowing read that’s genuinely unlike anything you’ve ever read before . . . Vellum has expanded fantasy’s limits like nothing published in years.”

–SFX (five-star “must-read” review)

“Duncan’s writing is fluent and powerful. He possesses an imagination capable of both conjuring worlds and capturing the intricacies of moments. Vellum is more than a novel; it’s a vision.”

–Jeffrey Ford, author of The Girl in the Glass

“A remarkably ambitious debut novel. For lovers of innovative fantasy, it’s a must-read.”

–Interzone

“Vellum is a revelation–the opening gambit in the career of a mind-blowing colossal talent whose impact will be felt for decades.”

–Jeff VanderMeer, author of City of Saints and Madmen

Descriere

A smash hit in England, this dark epic fantasy is an extraordinary, incendiary debut from a bold new talent. It is 2017, when a fallen angel and a renegade devil are about to settle a feud that reaches back to the beginnings of human existence.

Premii

- Spectrum Awards Winner, 2007

- Locus Awards Nominee, 2006