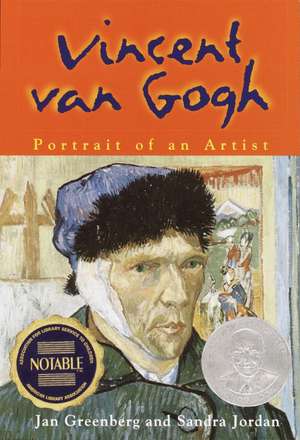

Vincent Van Gogh: Portrait of an Artist

Autor Jan Greenberg, Sandra Jane Jordanen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 dec 2002 – vârsta de la 10 ani

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

In a career spanning only a decade, Van Gogh painted many great works, yet fame eluded him. This lack of recognition increased his self-doubts and bitter disappointments. Today, however, Van Gogh stands as a giant among artists.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 37.98 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 57

Preț estimativ în valută:

7.27€ • 7.56$ • 6.00£

7.27€ • 7.56$ • 6.00£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 24 martie-07 aprilie

Livrare express 08-14 martie pentru 15.01 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780440419174

ISBN-10: 0440419174

Pagini: 132

Ilustrații: FULL-COLOR AND B&W PHOTOS

Dimensiuni: 132 x 197 x 7 mm

Greutate: 0.12 kg

Editura: Yearling Books

ISBN-10: 0440419174

Pagini: 132

Ilustrații: FULL-COLOR AND B&W PHOTOS

Dimensiuni: 132 x 197 x 7 mm

Greutate: 0.12 kg

Editura: Yearling Books

Extras

A Brabant Boy

1853-75

I have nature and art and poetry. If that is not enough what is?

--Letter to Theo, January 1874

ON MARCH 30, 1853, the handsome, soberly dressed Reverend Theodorus van Gogh entered the ancient town hall of Groot-Zundert, in the Brabant, a province of the Netherlands. He opened the birth register to number twenty-nine, where exactly one year earlier he sadly had written "Vincent Willem van Gogh, stillborn." Beside the inscription he wrote again "Vincent Willem van Gogh," the name of his new, healthy son, who was sleeping soundly next to his mother in the tiny parsonage across the square. The baby's arrival was an answered prayer for the still-grieving family.

The first Vincent lay buried in a tiny grave by the door of the church where Pastor van Gogh preached. The Vincent who lived grew to be a sturdy redheaded boy. Every Sunday on his way to church, young Vincent would pass the headstone carved with the name he shared. Did he feel as if his dead brother were the rightful Vincent, the one who would remain perfect in his parents' hearts, and that he was merely an unsatisfactory replacement? That might have been one of the reasons he spent so much of his life feeling like a lonely outsider, as if he didn't fit anywhere in the world.

Despite his dramatic beginning, Vincent had an ordinary childhood, giving no hint of the painter he would become. The small parsonage, with an upstairs just two windows wide under a slanting roof, quickly grew crowded. By the time he was six he had two sisters, Anna and Elizabeth, and one brother, Theo, whose gentle nature made him their mother's favorite. The youngest van Goghs, Wilhelmien (called Wil) and Cornelius, were born after Vincent went away to school.

Their mother, Anna Carbentus van Gogh, herself one of eight, came from an artistic background. Her father had been a bookbinder to the royal family. A gifted amateur artist who filled notebooks with drawings of plants and flowers, she thought Vincent had a pleasant talent that might be useful someday. She didn't suspect he would develop into a great artist. In fact she recalled only that he once modeled an elephant out of clay but smashed it when she and his father praised it more than he thought they should. For the same reason he tore up a drawing of a cat climbing a tree. It wasn't his artistic ability but his obstinate personality that left the biggest impression on his mother. That willful stubbornness turned up again and again as he grew older.

With a big family and a little house, the children spent a lot of time out of doors. The freckled, red-haired Vincent, solitary by nature, often wandered by himself in the fields and heaths that surrounded the parsonage. He became familiar with the seasons of planting and harvest and with the hardworking local farm families whose labors connected them to the soil. The strong feeling he developed for the rural landscape of Brabant and the lives of its peasants would be one of the major influences in his life.

Mostly he did what boys like to do. He collected bugs and birds' nests. He teased his sisters. He built sand castles in the garden with Theo. Sometimes he invented games for all of them to play. After one exciting day his brothers and sisters thanked Vincent by staging a ceremony, and, with mock formality, presented him with a rosebush from their father's garden.

Theodorus, Vincent's father, a pastor from a long line of pastors, was one of eleven children. His family had been members of the bourgeois for generations, with middle-class connections all over the Netherlands. People in Groot-Zundert called Mr. van Gogh the "Handsome Pastor" for his good looks but found his long sermons boring. The province of Brabant, where the village was located, was a farming district populated mainly by Catholics. The pastor's Dutch Reformed congregation had only 120 members, and as a result, he didn't make much money. Family finances were tight. Vincent attended the village school until his parents, worried that the peasant children were making their son rough, hired a governess to teach the children at home.

When Vincent was only eleven, his parents sent him away to Mr. Provily's school in the nearby town of Zevenbergen. Waving goodbye on the steps of the school, he watched his mother and father's little yellow carriage drive down the road until it disappeared. The gray autumn sky matched his mood. His parents noticed how sad he looked. A few weeks later, as Vincent stood in the corner of the playground, someone told him he had a visitor. His father had come back to check on him. Overcome with emotion, Vincent fell on his father's neck, but still he had to remain in school. Though he would visit and even live at home in the years to follow, it was the beginning of what he felt to be a life of exile.

Vincent's schoolmasters didn't consider him an outstanding student. He was intelligent but no scholar. Still, after two years at Mr. Provily's, Vincent moved up. His parents valued education, and they sent their eldest son to an impressive new school in the nearby town of Tilburg--King Willem II State Secondary School.

The school had nine teachers for only thirty-six pupils, so Vincent's days were busy. He took a long list of courses: Dutch, German, French, English, arithmetic, history, geography, geometry, botany, zoology, gymnastics, calligraphy, linear drawing, and freehand drawing. The drawing classes were considered part of a well-rounded gentleman's education, not preparation for a career. He ended his first term well enough to be one of five boys in his class of ten who were promoted. However, in March of the following year, the family took him out of school, probably for financial reasons. He left with a passion for novels and poetry and a working knowledge of four languages. In that era many children finished school at fifteen and apprenticed in a trade, but Vincent sat at home for more than a year before the family reached a decision about his future.

Three of his father's five brothers--Uncle Vincent (whose nickname was Cent), Uncle Cor, and Uncle Heim--owned flourishing art galleries, the charismatic Uncle Cent being the most successful of the three. The French firm of Goupil et Cie, with headquarters in Paris and branches in London, Brussels, and The Hague, had purchased his gallery and made him a partner. Cent, now semiretired for health reasons, maintained an interest in the firm. Married but with no children of his own, he took an active role in the lives of his young nephews and nieces. So Vincent, his namesake, was offered an opportunity to learn the art business.

In July 1869 Vincent began his apprenticeship in The Hague, an elegant and historic town that was the center of the Netherlands government. The Goupil gallery branch there looked like an upper-class drawing room, not a commercial establishment. Doorways between the rooms were draped with swags of heavy fabric trimmed with fringe. Oriental rugs covered the floors. On the brocaded walls, gold-framed pictures hung all the way to the ceiling. Customers at Goupil could see for themselves how the paintings would look in their own richly decorated houses.

1853-75

I have nature and art and poetry. If that is not enough what is?

--Letter to Theo, January 1874

ON MARCH 30, 1853, the handsome, soberly dressed Reverend Theodorus van Gogh entered the ancient town hall of Groot-Zundert, in the Brabant, a province of the Netherlands. He opened the birth register to number twenty-nine, where exactly one year earlier he sadly had written "Vincent Willem van Gogh, stillborn." Beside the inscription he wrote again "Vincent Willem van Gogh," the name of his new, healthy son, who was sleeping soundly next to his mother in the tiny parsonage across the square. The baby's arrival was an answered prayer for the still-grieving family.

The first Vincent lay buried in a tiny grave by the door of the church where Pastor van Gogh preached. The Vincent who lived grew to be a sturdy redheaded boy. Every Sunday on his way to church, young Vincent would pass the headstone carved with the name he shared. Did he feel as if his dead brother were the rightful Vincent, the one who would remain perfect in his parents' hearts, and that he was merely an unsatisfactory replacement? That might have been one of the reasons he spent so much of his life feeling like a lonely outsider, as if he didn't fit anywhere in the world.

Despite his dramatic beginning, Vincent had an ordinary childhood, giving no hint of the painter he would become. The small parsonage, with an upstairs just two windows wide under a slanting roof, quickly grew crowded. By the time he was six he had two sisters, Anna and Elizabeth, and one brother, Theo, whose gentle nature made him their mother's favorite. The youngest van Goghs, Wilhelmien (called Wil) and Cornelius, were born after Vincent went away to school.

Their mother, Anna Carbentus van Gogh, herself one of eight, came from an artistic background. Her father had been a bookbinder to the royal family. A gifted amateur artist who filled notebooks with drawings of plants and flowers, she thought Vincent had a pleasant talent that might be useful someday. She didn't suspect he would develop into a great artist. In fact she recalled only that he once modeled an elephant out of clay but smashed it when she and his father praised it more than he thought they should. For the same reason he tore up a drawing of a cat climbing a tree. It wasn't his artistic ability but his obstinate personality that left the biggest impression on his mother. That willful stubbornness turned up again and again as he grew older.

With a big family and a little house, the children spent a lot of time out of doors. The freckled, red-haired Vincent, solitary by nature, often wandered by himself in the fields and heaths that surrounded the parsonage. He became familiar with the seasons of planting and harvest and with the hardworking local farm families whose labors connected them to the soil. The strong feeling he developed for the rural landscape of Brabant and the lives of its peasants would be one of the major influences in his life.

Mostly he did what boys like to do. He collected bugs and birds' nests. He teased his sisters. He built sand castles in the garden with Theo. Sometimes he invented games for all of them to play. After one exciting day his brothers and sisters thanked Vincent by staging a ceremony, and, with mock formality, presented him with a rosebush from their father's garden.

Theodorus, Vincent's father, a pastor from a long line of pastors, was one of eleven children. His family had been members of the bourgeois for generations, with middle-class connections all over the Netherlands. People in Groot-Zundert called Mr. van Gogh the "Handsome Pastor" for his good looks but found his long sermons boring. The province of Brabant, where the village was located, was a farming district populated mainly by Catholics. The pastor's Dutch Reformed congregation had only 120 members, and as a result, he didn't make much money. Family finances were tight. Vincent attended the village school until his parents, worried that the peasant children were making their son rough, hired a governess to teach the children at home.

When Vincent was only eleven, his parents sent him away to Mr. Provily's school in the nearby town of Zevenbergen. Waving goodbye on the steps of the school, he watched his mother and father's little yellow carriage drive down the road until it disappeared. The gray autumn sky matched his mood. His parents noticed how sad he looked. A few weeks later, as Vincent stood in the corner of the playground, someone told him he had a visitor. His father had come back to check on him. Overcome with emotion, Vincent fell on his father's neck, but still he had to remain in school. Though he would visit and even live at home in the years to follow, it was the beginning of what he felt to be a life of exile.

Vincent's schoolmasters didn't consider him an outstanding student. He was intelligent but no scholar. Still, after two years at Mr. Provily's, Vincent moved up. His parents valued education, and they sent their eldest son to an impressive new school in the nearby town of Tilburg--King Willem II State Secondary School.

The school had nine teachers for only thirty-six pupils, so Vincent's days were busy. He took a long list of courses: Dutch, German, French, English, arithmetic, history, geography, geometry, botany, zoology, gymnastics, calligraphy, linear drawing, and freehand drawing. The drawing classes were considered part of a well-rounded gentleman's education, not preparation for a career. He ended his first term well enough to be one of five boys in his class of ten who were promoted. However, in March of the following year, the family took him out of school, probably for financial reasons. He left with a passion for novels and poetry and a working knowledge of four languages. In that era many children finished school at fifteen and apprenticed in a trade, but Vincent sat at home for more than a year before the family reached a decision about his future.

Three of his father's five brothers--Uncle Vincent (whose nickname was Cent), Uncle Cor, and Uncle Heim--owned flourishing art galleries, the charismatic Uncle Cent being the most successful of the three. The French firm of Goupil et Cie, with headquarters in Paris and branches in London, Brussels, and The Hague, had purchased his gallery and made him a partner. Cent, now semiretired for health reasons, maintained an interest in the firm. Married but with no children of his own, he took an active role in the lives of his young nephews and nieces. So Vincent, his namesake, was offered an opportunity to learn the art business.

In July 1869 Vincent began his apprenticeship in The Hague, an elegant and historic town that was the center of the Netherlands government. The Goupil gallery branch there looked like an upper-class drawing room, not a commercial establishment. Doorways between the rooms were draped with swags of heavy fabric trimmed with fringe. Oriental rugs covered the floors. On the brocaded walls, gold-framed pictures hung all the way to the ceiling. Customers at Goupil could see for themselves how the paintings would look in their own richly decorated houses.

Notă biografică

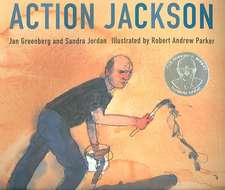

Jan Greenberg and Sandra Jordan

Premii

- Robert F. Sibert Informational Book Award Honor Book, 2002