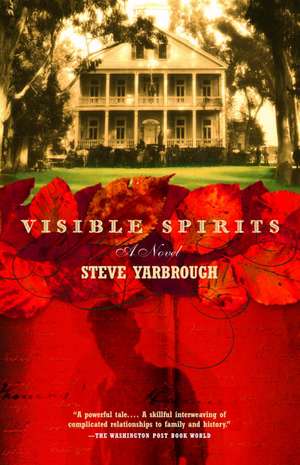

Visible Spirits: Vintage Contemporaries

Autor Steve Yarbroughen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 iul 2002

Into this charged atmosphere rides Tandy Payne–prodigal son of a prominent planter and brother of the current mayor, and a dissolute gambler looking to reclaim the family estate. When he takes advantage of a perceived slight from the town’s black postmistress, the ensuing clash with his principled brother results in a harrowing confrontation. Fueled by dark and brutal memories, their familial dispute quickly spreads through the countryside. Steve Yarbrough confronts character with morality, reason with blood, in this moving novel that explores the farthest boundaries of human nature.

Din seria Vintage Contemporaries

-

Preț: 109.95 lei

Preț: 109.95 lei -

Preț: 101.80 lei

Preț: 101.80 lei -

Preț: 96.52 lei

Preț: 96.52 lei -

Preț: 107.46 lei

Preț: 107.46 lei -

Preț: 91.77 lei

Preț: 91.77 lei -

Preț: 101.88 lei

Preț: 101.88 lei -

Preț: 111.51 lei

Preț: 111.51 lei -

Preț: 119.87 lei

Preț: 119.87 lei -

Preț: 99.75 lei

Preț: 99.75 lei -

Preț: 97.34 lei

Preț: 97.34 lei -

Preț: 111.92 lei

Preț: 111.92 lei -

Preț: 117.87 lei

Preț: 117.87 lei -

Preț: 95.92 lei

Preț: 95.92 lei -

Preț: 113.56 lei

Preț: 113.56 lei -

Preț: 132.88 lei

Preț: 132.88 lei -

Preț: 108.09 lei

Preț: 108.09 lei -

Preț: 115.42 lei

Preț: 115.42 lei -

Preț: 106.04 lei

Preț: 106.04 lei -

Preț: 96.11 lei

Preț: 96.11 lei -

Preț: 87.84 lei

Preț: 87.84 lei -

Preț: 99.51 lei

Preț: 99.51 lei -

Preț: 105.41 lei

Preț: 105.41 lei -

Preț: 99.30 lei

Preț: 99.30 lei -

Preț: 120.26 lei

Preț: 120.26 lei -

Preț: 103.74 lei

Preț: 103.74 lei -

Preț: 100.98 lei

Preț: 100.98 lei -

Preț: 100.76 lei

Preț: 100.76 lei -

Preț: 89.09 lei

Preț: 89.09 lei -

Preț: 115.94 lei

Preț: 115.94 lei -

Preț: 101.24 lei

Preț: 101.24 lei -

Preț: 125.13 lei

Preț: 125.13 lei -

Preț: 89.50 lei

Preț: 89.50 lei -

Preț: 100.35 lei

Preț: 100.35 lei -

Preț: 139.63 lei

Preț: 139.63 lei -

Preț: 90.35 lei

Preț: 90.35 lei -

Preț: 106.45 lei

Preț: 106.45 lei -

Preț: 89.91 lei

Preț: 89.91 lei -

Preț: 107.92 lei

Preț: 107.92 lei -

Preț: 77.02 lei

Preț: 77.02 lei -

Preț: 125.21 lei

Preț: 125.21 lei -

Preț: 96.93 lei

Preț: 96.93 lei -

Preț: 112.11 lei

Preț: 112.11 lei -

Preț: 83.94 lei

Preț: 83.94 lei -

Preț: 97.15 lei

Preț: 97.15 lei -

Preț: 105.82 lei

Preț: 105.82 lei -

Preț: 88.62 lei

Preț: 88.62 lei -

Preț: 111.76 lei

Preț: 111.76 lei -

Preț: 129.78 lei

Preț: 129.78 lei -

Preț: 100.57 lei

Preț: 100.57 lei

Preț: 90.64 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 136

Preț estimativ în valută:

17.34€ • 18.11$ • 14.35£

17.34€ • 18.11$ • 14.35£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15-29 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780375725777

ISBN-10: 0375725776

Pagini: 288

Dimensiuni: 132 x 203 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.21 kg

Editura: Vintage Publishing

Seria Vintage Contemporaries

ISBN-10: 0375725776

Pagini: 288

Dimensiuni: 132 x 203 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.21 kg

Editura: Vintage Publishing

Seria Vintage Contemporaries

Notă biografică

Steve Yarbrough is the author of three collections of stories and a novel, The Oxygen Man, which received the Mississippi Authors’ Award, the California Book Award and a third from the Mississippi Institute of Arts and Letters. A native of the Delta town of Indianola, he now lives in Fresno, California.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

The mud on Main Street was half a foot deep and mixed with enough horse shit to make him wish he had something to clamp over his nose. But he’d lost his handkerchief on the train coming up, and anyway, it was stained with blood: in New Orleans a fellow had punched him in the mouth. He couldn’t remember who it was, though he did recall how much it hurt.

A supply wagon loaded with hundred-pound sacks of feed grain and hog shorts waited in front of Rosenthal’s General Merchandise, and a couple horses were tied up in front of the hardware. But he knew, because he knew his brother, that Leighton would already be in—he’d probably been at the office since five or five-thirty. He went to bed every night at nine o’clock and rose at four so he could get an hour’s worth of reading done before setting to work. He’d always done that and always would, especially now that he had two jobs instead of one.

The legend on the window said loring weekly times. The building had once been a saloon, but that closed down back in ’96

when the drys won the local option election. Leighton had played a role in their favor, editorializing at length, arguing that the whole community should be outraged at the sight of drunks staggering along the sidewalk, bumping into women.

Through the window this morning, Tandy could see him sitting at his rolltop desk, back where the poker tables used to be, reading a big leather-bound volume. He wore a gray suit, and Tandy knew the suit was clean and fresh-smelling, that the collar of his white shirt had been pressed this very morning. He knew who had pressed it, too.

The door was unlocked; he opened it and stepped inside. Blank sheets of newspaper were stacked on the floor near an old copper-plated handpress, and on the counter were metal baskets with copy in them. A Western Newspaper Union calendar hung on one wall. Instead of smelling like cigarettes and whiskey, as it used to, the place stank now of ink and dust.

Leighton didn’t even look up. “I was wondering when I’d hear from you,” he said.

Tandy stomped each boot on the floor, and clots of mud flew off.

Leighton laid the book down. He stared at Tandy’s boots. “Most folks would’ve stomped the mud off outside.”

“Course, I’m not most folks. I’m family.”

Leighton stood. As always, when Tandy had been away for a while, the size of his brother took him by surprise. Tandy was not a small man himself, but Leighton stood six foot five, an inch taller than their father, and even though he lacked their father’s weight, he could still fill a room by himself. When Leighton was present, Tandy felt he had less of everything—less space to move around in, less air to breathe.

A big lightbulb hung from the ceiling. Pointing, Tandy said, “I heard y’all had got electric power.”

The civic booster in his brother asserted itself: you could almost see his chest swell. “Got it last fall. Right now, it’s only on from six till midnight, but that’s a big help to us on Wednesday evening, when we’re actually printing the paper.” He smiled and crossed his arms. “You hear what happened over at the livery stables?”

“No.”

“Uncle Billy Heath decided he needed him some electric power. Said he wanted to be able to check on his horses without worrying about toting a coal-oil lamp in there and having one of ’em kick it over and set the whole place afire. So he had Loring Light, Ice and Coal string a cable in and suspend a big old bulb from the rafters. When they turned on the power, all the horses went crazy. They kicked open the stall doors and took off down Main Street. One of ’em ran right over Uncle Billy. Broke his arm in two places.”

Tandy laughed. Eight or ten years ago, in a poker game in this very building, Uncle Billy Heath had beaten him out of a good-looking saddlebred mare. Tandy had owned the mare for only three or four hours before losing her, and it pleased him now to think maybe she was the one who’d broken Uncle Billy’s arm.

“When a person leaves town,” he said, “all sorts of things start happening. You don’t hardly know the place when you get back.”

“Yeah, there’s a few things that have changed, I guess.” Leighton stuck his hands in his pockets. “I imagine you know A. L. Gunnels passed on.”

“No, I hadn’t heard that. Who’s the new mayor?”

“The truth is, you’re looking at him.”

This was the moment Tandy had dreaded, the worst thing about coming back. At two o’clock this morning, as he sat on a hard bench at the depot, batting away mosquitoes and doing his best to stay awake, he had imagined what it was going to feel like when he stood face-to-face with his brother and acknowledged another of Leighton’s successes, and it had almost been enough to make him jump on the next train leaving town. The problem was, he didn’t have the money to buy a ticket on the next train. He’d traveled just as far as he could.

“Well now, damn if we don’t have a politician in the family,” he said. “Congratulations.”

He offered Leighton his hand. When his brother took it, Tandy felt how puny his own fingers were. The handshake almost crushed them.

“All I plan to do’s serve out the rest of A.L.’s term. Some folks got together and asked me to do it, and I felt like I couldn’t say no. I don’t know if congratulations are in order, though. Maybe condolences would be more appropriate.”

“How come?”

“We’ve got some troublesome issues to confront. For instance, there’s a group of folks who want to pass an ordinance making it illegal to construct any more frame buildings, because they’re scared a fire’ll sweep through and burn the whole town down. But brick’s expensive, so some folks are claiming this ordinance’ll discourage new businesses and retard progress—retard progress is a phrase you hear in the board meetings every two or three minutes. People get all heated up over stuff like that, and by virtue of being both mayor and editor of the local paper, I’m smack-dab in the middle.”

If being smack-dab in the middle displeased him, Tandy couldn’t tell it. Leighton seemed, as always, quite happy with himself.

He did not, however, look particularly happy with Tandy. He let his eyes travel down his brother’s torso to his pants, which a year ago had been white but were now a dingy cream color, with spots of mud and dried blood on the knees. The boots had last been shined five or six months back and were in need of repair.

“What happened?” he said. “Somebody catch you dealing from the bottom of the deck?”

“Nobody does that anymore.”

“Well, it looks like somebody caught you doing something.”

Nobody had caught him doing anything. A little more than a week ago, he’d been in a game where the pot had reached six thousand dollars, and a fellow he’d never seen before, a wiry little man with a funny accent and a gold watch chain that had a miniature jockey’s cap and a saddle hanging from it, had convinced him and the other three players to follow him over to the bank, where he’d request a loan based on his hand. Tandy had bought the key to the deck, he held a strong hand, and it never crossed his mind, not for one minute, that one of the other players might have bought the key, too. He believed he’d found the perfect sucker. He believed it right up until the man with the watch chain—having received his loan from a banker who Tandy figured must not know the first thing about poker—played a king and four aces.

The money hadn’t been Tandy’s to lose. People wanted that money, believing it was theirs, and if you looked at things in a certain way, they were right. He’d heard that if he didn’t leave town, somebody might kill him.

“You’re broke, aren’t you?” Leighton said.

“Temporarily insolvent’s how I’d put it.”

“Temporary’s got its limits. After a while, temporary becomes permanent.”

“There was a three-day period six months ago when I could have bought you and everything you call yours.”

“No,” Leighton said, “you couldn’t have.”

For a moment, while Leighton stood there facing him, letting his words sink in, Tandy hated his brother. It wasn’t the first time, nor would it be the last. But he knew that if he could just keep a grip on himself for a few more seconds, the moment of hating would pass and he’d be left with the same old bunch of feelings, which were far too complicated to bear a single name.

Leighton turned, walked back over to his desk. He flipped open a ledger that lay near his typewriter. He made a show of staring at it, running his finger down the page as if he were checking figures. “Where are you staying?”

“Thought I’d take a room at Miss Rosa’s.”

“Room and board at Miss Rosa’s is about four dollars a week. I imagine you’re a few dollars short?”

Tandy was tired: he hadn’t slept for two days or had a drink for three, and all he really wanted was to get into a nice soft bed with a bottle of whiskey and drink till he passed out cold. But one thing you could always do when you couldn’t do anything better was bluff. If nothing else, it kept you in the game. So he did his best to sound rakish, untroubled.

“Briefly.”

Leighton opened a desk drawer and took out a metal box. He raised the lid, pulled a few bills out, counted and laid them on the desk, then put the box back in the drawer. The entire operation probably took only a minute or so, but to Tandy it felt like ten years.

Leighton picked up the stack of bills and walked over and handed them to him.

“Thanks,” Tandy said.

“Sarah and Will’ll want to see you. Why don’t you come over tonight and eat supper?”

“All right.” He crammed the bills into his pocket. “Leighton . . . that board you mentioned? Has it got the power to give out jobs?”

“Jobs?” Leighton said, sounding as if he couldn’t believe he’d heard right.

“You know. City jobs.”

“Yeah,” Leighton said. “It’s got the power to hire folks to sweep up the marshal’s office and cart garbage over to the town dump. You want to cart garbage, Tandy? Is that what you’re saying?”

Beneath Tandy’s feet, the floorboards creaked. He was sweating now. He smelled his own odor.

Through the inverted letters on the front window, Leighton watched his brother shamble across the intersection at Main and First, his head down, his eyes on the ground. He looked whipped, the very picture of failure and dejection, until he heard the sound of a horse’s hooves and looked up. Sally Stark, the wife of a local planter, was driving along in a carriage. Instantly, Tandy’s bearing changed. Straightening himself up to his full height, he doffed his fedora and swept it through the air, then executed a graceful bow.

Sally Stark pulled back on the reins, and the horse slowed down. Leighton watched while her face broke into a smile. Her lips formed a single word.

Tandy!

The house stood on the banks of Loring Bayou.A big white house surrounded by a white picket fence, it had a broad veranda overhung by cedars, pecan trees and locusts. Leighton had designed it himself, in concert with his father-in-law, and it had cost him $2,500. Tonight, it was brightly lit.

Walking up from the street, he heard music: Sarah playing the piano, Tandy singing “Danny Boy.” For a moment, he stopped and listened. He’d always loved hearing Tandy sing, but if he was in the room while the singing was going on, Leighton had to shut his eyes to enjoy it. Seeing the man behind the voice ruined the effect.

They had just finished the final chorus when he opened the door. Tandy was clean now, his pants and jacket sparkling white, his boots shining in the lamplight, though they still looked a little worn around the toes. He’d shaved and waxed his mustache and combed his hair.

He stood beside the piano. Sarah’s cheeks were rosy, and she was smiling up at him. Upstairs, in a walnut cabinet near the bed, there was a photograph of her sitting beside Tandy in a buggy. In the picture, she wore a lace dress and a tall hat with taffeta trim, and she was looking at him with that same bright smile on display.

Tandy was at home among women, always able to make them smile, whereas Leighton never quite felt comfortable in their presence. He liked them and wanted to be around them, but whenever they were near, he became aware of his size. He tended to bend toward them, ducking his head in compensation. More often than not, they instinctively pulled away.

“That sounded pretty darn good,” he said. He removed his hat, hung it on the rack and walked over and laid his hand on Sarah’s shoulder. “Maybe y’all could go on the road and make some money.”

“Tandy can’t make money. It’s beneath him.”

“Well, I wouldn’t say it’s beneath me. I’d say it’s somewhere off to the side.”

“It seems there are some people in New Orleans to whom Tandy owes more than six thousand dollars.”

“Give or take a dollar or two.”

“And they’ve suggested he might come to harm.”

“They’re not bad folks. They’re just a little too quick to rile.”

“So Tandy is here, as it were, in hiding.”

She hadn’t looked at Leighton since he’d walked in. He willed himself now to lift his hand from her shoulder, but he couldn’t. She was wearing a voile frock so sheer his fingertips could feel her pulse through the fabric. He felt the heat of her body as well, and something else—moisture, the sheen of perspiration on her skin. His free hand rose as if of its own volition; he almost laid it on her other shoulder and caressed her. What stopped him was the sight of a blackish smear on his palm. His hands had always looked rough, and now they frequently bore ink stains. He could never quite get them all off.

“Tandy can’t hide,” he said. “Tandy draws crowds like a dog draws fleas.”

They sat at the supper table, lingering over the remains of an apple pie Sarah had baked that afternoon. Tandy was telling a story about his adventures in New Orleans.

“So the driver, he looks over his shoulder at me and says, ‘The one on the left, sir, he rough-gaited, and the one on the right, well, she a shirker. This crushed gravel on the street, it get up in the frog on the horse’s foot, and it can make ’em go lame. Well, the one on the right there, she know I know that, so she start acting like that what’s done happened. But there’s one other thing she know I know. She know I know her just as well as she know me.’ And you know what the driver did then?”

“No,” Will said. “What’d he do, Uncle Tandy?”

“Well, he pulled the whip out of the socket and whacked the mare on her tail. But instead of picking up her pace, she got her tail up over the dashboard and cut loose with about five or six pounds of the stinky stuff.”

Will burst out laughing.

“Tandy!” Sarah said.

“The old nigger was naturally the color of blackstrap molasses, but when the horse did that, he gagged and turned green. He had to pull his hat off and hold it over his face all the way back to Jackson Square. Tell you the truth, it like to killed me, too.”

“Yeah,” Leighton said. “It just about killed me now to listen to it.”

He glanced at Will. He was nine, a tall skinny boy who sometimes got so excited he forgot to eat. He also forgot to sleep.

“It’s about time for you to go to bed, son.”

“Daddy!” Will balled his hands up into fists.

“William Lee Payne,” Sarah said. “Can you imagine your father or your uncle behaving like that if their father had told them to go to bed?”

Face sullen, Will kissed Sarah good night, then walked over and leaned against Leighton.

“Good night, son.”

“Night.”

On his way out, he paused long enough to shake hands with Tandy. “You’ll still be here tomorrow?”

“For tomorrow and for many days to come.”

“And you’ll tell me some more stories?”

Tandy leaned back in his chair. Light glinted off the buttons on his jacket. “I’ll tell you stories,” he said, “that’ll make hair spring up in your armpits.” He grabbed Will and tickled him under the arms, and Will shrieked and ran for the stairs.

Tandy watched him race up them two at a time. “He’s going to be a big one.”

“Well, there aren’t any small ones in our family.”

“I’m the runt of the litter.”

“It wasn’t a very big litter to be the runt of,” Sarah said.

“It was litter enough. Sometimes, when I was sitting at the table like this, across from Leighton and Daddy, I felt like I lived among giants.”

“Oh, come on. Till I was fourteen or fifteen, you were just as tall as I was.”

“I felt like I lived among giants. A war hero for a father and a brother who was clearly destined for the greater walks of life. And now, in addition to being a man of letters, he’s the mayor.”

“Yeah, and these civic posts are highly distinguished. That’s why last year we reduced the membership on the Board of Aldermen from five to four. Couldn’t convince a fifth man to run.”

“Speaking of civics,” Tandy said, “what else is new around town? Old Percy Stancill still buying up every piece of land he can?”

“Owns upwards of ten thousand acres.”

“Didn’t his wife pass on?”

“Two wives passed on. He’s on the third one now.”

“Good for him.”

“You probably noticed the hitching posts along Main,” Sarah said. “Now it’s illegal to tether the beasts to porch columns. And Rosenthal’s sells ice. They bring it up the river on a boat, and he stores it in sawdust. Oh, and we have a Negro serving as postmistress.”

You could tell, knowing Tandy, when something aroused his interest. If he was sitting at a table, he would place both hands palm-down before him, as if he meant to push himself up. The hands were out there now. “A colored postmistress?” he said. “How and when did that come about?”

Leighton picked up his coffee cup and glanced at Sarah.

She said, “I’ll get some more.”

He waited until she’d left the dining room. “The postmistress got the appointment during McKinley’s first term,” he said. “I think Jim Hill recommended her.”

“One of ’em scratching another one’s back.”

“Well, somebody’s always scratching somebody’s back, Tandy. I reckon colored folks itch from time to time, same as we do.”

“Yeah,” Tandy said, “I guess so. So who is she—this postmistress?”

Leighton lifted his fork and picked at the remains of his pie. “Actually, you know her.”

He looked up just as the light went on in his brother’s eyes.

Wearing her carpenter’s apron, she moved down the row, pulling those speckled butter beans off the vines and dropping them into her pockets. She’d planted late this year, toward the end of April. Now the garden was full of beans and squash, cucumbers and tomatoes. The cantaloupes weren’t looking too good, but you couldn’t have everything. She had plenty.

The garden was hers: she’d laid the rows out, erected oak posts at the ends of her bean patch, strung wire between them and tied saplings to the wire with rag string; she’d sown in springtime and hoed on June days so hot she almost swooned. Seaborn P. Jackson was nothing if not industrious, but he would not lift a finger to plant or tend a garden. Dirt, as far as he was concerned, was a substance to stand on. He derived no pleasure from its presence on his hands.

First thing each morning, he heated water for washing. In the back room, behind a gray curtain, he stood in the washtub and bathed himself meticulously, his bald head visible above the curtain rod. Then he shaved and brushed his teeth with baking soda, and once he was finished, he donned his suit and tie. He would not appear at the breakfast table until fully dressed for business.

He sold insurance—health, life and burial, mostly burial—for the Independent Life Insurance Company. For no more than twenty cents a week, you could assure yourself a hundred-dollar funeral. Seaborn himself oversaw the proceedings and was fond of stating he’d never let a dead person down. People called him “the policy man.” Behind his back they called him “a biggity nigger,” or just “Biggity.”

She walked over to the back porch and emptied the beans into a pan, then carried it inside. She was sweating now, her legs and back and armpits wet. She went out back and, after scanning the shrubs lining the rear of the yard, she pulled her blouse off. She primed the pitcher pump, then began sloshing cool water on her arms and her belly, her shoulders and breasts. Seaborn had warned her never to do this. A white man had stopped him on the street one day right in front of Rosenthal’s and told him that his son and one other boy had been walking by one day and noticed his wife out back with her shirt off.

“It’s fine for y’all to live where you live,” the man had said, “but there’s a certain amount of responsibility that goes with the ground.”

The only way the man’s son and the other boy could have noticed her with her top off would have been to squat and peer in through the bushes, and while Seaborn surely knew that, he just as surely never said it.

“Don’t sir ’em,” she’d once heard him advise a young man of their acquaintance. “Suh ’em. There are sounds we can make which cause them discomfort, and an r on the end of the word sir is one of them. Say uhh after sss. Lay down hard on that last syllable, draw it out, make that good lasting impression, and they won’t notice you again for three or four months.”

So Seaborn would have rolled his eyes, nodding his head at this word to the wise, then come down hard on that last syllable. “Yes, suh.” The man would quit noticing him, though he and his son and his son’s friend would keep right on noticing her.

. . .

The post office stood directly across the street from Rosenthal’s, in between the Bank of Loring and Farmer’s Drugstore. This morning, when she got there, a mail sack was propped against the door. Sometimes the train came a few minutes early, and even though she’d asked the man who drove the wagon for the C & G not to leave the mail standing out front, where just anybody could take it, he was white and did as he pleased.

She unlocked the door, then grabbed the sack by its drawstring. She spent the next half hour distributing the mail, popping envelopes into boxes, bending over and glancing through the little windows from time to time to make sure nobody had entered the lobby without her hearing them. To keep customers waiting was not her policy. She’d even installed a telephone at her own expense so people could call and find out if they had any mail.

She’d just finished putting the mail out when the front door creaked open. She grabbed a rag and wiped the ink off her hands, then straightened her hair and walked out to the counter.

It was Blueford. He had his hands in his pockets and was wearing the funny-looking little tricornered white hat Rosenthal insisted on during business hours. The hat would’ve looked ridiculous on most men—she could scarcely imagine it atop Seaborn’s bald pate—but somehow Blueford always bore it with dignity, even when he had a fifty-pound sack of cornmeal balanced on his shoulder.

“What you doin’ this morning, Loda?”

“Same as every morning.”

“Mail done come yet?”

“Sure has.”

“I don’t reckon I got nothing from my auntie, did I?”

She kept the mail for general delivery stacked on a shelf behind the counter. There was only a handful of items today. She went through them quickly, finding nothing for Blueford. “Sorry. I hope it wasn’t money you were expecting.”

“Not hardly. She done supposed to had a picture made of my cousin’s little baby. I ain’t never yet seen him.”

“Is this the aunt that lives in Vicksburg?”

“Aunt Florice. Only one I got. Only natural aunt, anyway. Least as far as I know.”

He must have noticed that her gaze had shifted, that she was looking beyond him, at the street. A couple wagons passed by, though no one was walking toward the post office. Nonetheless, he did what he knew she needed him to do: he began to take his leave.

“Well,” he said, “old Rosenthal got twenty thousand things he expect me to do in the next twenty minutes.”

He smiled at her and walked over to the door. He watched the street for a moment. Then, as if it were an afterthought—which it was not, because Blueford never entertained afterthoughts—he said, “By the way. Guess who I just saw this morning?”

“Who?”

“That younger one.”

“Oh,” she said. “So he’s back.”

“Yeah.” He opened the door. “Reckon wherever he was at, they must of done run out of trouble.”

Trouble.

She worried about it—you always had to—though she hadn’t seen much of it in a pretty good while. She was not the only Negro in Mississippi with a government appointment, but she was the only one in Loring. Add to that the fact she and Seaborn lived a few yards north of the railroad tracks and owned a twenty percent interest in Rosenthal’s, and you became somebody folks couldn’t help but pay attention to.

At dusk she closed the office, stepped around the corner at Main and First on her way home, and ran right into a white man, her head actually striking his chest. She bounced back and was about to apologize when she saw who it was.

“Oh, Loda,” he said. “I’m sorry. I should’ve been watching where I was going.”

“No,” she said. “It’s my fault.”

“I didn’t hurt you, did I?”

The truth was, her nose stung pretty good. “No,” she said. Then: “Excuse me. No sir.”

“Don’t do that. Please.”

She was looking up into his face. She could see his features distinctly: the square chin, the perfectly shaped nose, the powder blue eyes. He’d recently cut himself shaving; there was a nick near one corner of his mouth.

“It looks to me,” she said, “like your daddy could’ve done a better job teaching you to use a razor.” She stood back to observe her last word’s effect: averted eyes, a faint bobbing of his Adam’s apple, nothing more.

“I hear your brother’s back in town,” she said, then walked on.

A supply wagon loaded with hundred-pound sacks of feed grain and hog shorts waited in front of Rosenthal’s General Merchandise, and a couple horses were tied up in front of the hardware. But he knew, because he knew his brother, that Leighton would already be in—he’d probably been at the office since five or five-thirty. He went to bed every night at nine o’clock and rose at four so he could get an hour’s worth of reading done before setting to work. He’d always done that and always would, especially now that he had two jobs instead of one.

The legend on the window said loring weekly times. The building had once been a saloon, but that closed down back in ’96

when the drys won the local option election. Leighton had played a role in their favor, editorializing at length, arguing that the whole community should be outraged at the sight of drunks staggering along the sidewalk, bumping into women.

Through the window this morning, Tandy could see him sitting at his rolltop desk, back where the poker tables used to be, reading a big leather-bound volume. He wore a gray suit, and Tandy knew the suit was clean and fresh-smelling, that the collar of his white shirt had been pressed this very morning. He knew who had pressed it, too.

The door was unlocked; he opened it and stepped inside. Blank sheets of newspaper were stacked on the floor near an old copper-plated handpress, and on the counter were metal baskets with copy in them. A Western Newspaper Union calendar hung on one wall. Instead of smelling like cigarettes and whiskey, as it used to, the place stank now of ink and dust.

Leighton didn’t even look up. “I was wondering when I’d hear from you,” he said.

Tandy stomped each boot on the floor, and clots of mud flew off.

Leighton laid the book down. He stared at Tandy’s boots. “Most folks would’ve stomped the mud off outside.”

“Course, I’m not most folks. I’m family.”

Leighton stood. As always, when Tandy had been away for a while, the size of his brother took him by surprise. Tandy was not a small man himself, but Leighton stood six foot five, an inch taller than their father, and even though he lacked their father’s weight, he could still fill a room by himself. When Leighton was present, Tandy felt he had less of everything—less space to move around in, less air to breathe.

A big lightbulb hung from the ceiling. Pointing, Tandy said, “I heard y’all had got electric power.”

The civic booster in his brother asserted itself: you could almost see his chest swell. “Got it last fall. Right now, it’s only on from six till midnight, but that’s a big help to us on Wednesday evening, when we’re actually printing the paper.” He smiled and crossed his arms. “You hear what happened over at the livery stables?”

“No.”

“Uncle Billy Heath decided he needed him some electric power. Said he wanted to be able to check on his horses without worrying about toting a coal-oil lamp in there and having one of ’em kick it over and set the whole place afire. So he had Loring Light, Ice and Coal string a cable in and suspend a big old bulb from the rafters. When they turned on the power, all the horses went crazy. They kicked open the stall doors and took off down Main Street. One of ’em ran right over Uncle Billy. Broke his arm in two places.”

Tandy laughed. Eight or ten years ago, in a poker game in this very building, Uncle Billy Heath had beaten him out of a good-looking saddlebred mare. Tandy had owned the mare for only three or four hours before losing her, and it pleased him now to think maybe she was the one who’d broken Uncle Billy’s arm.

“When a person leaves town,” he said, “all sorts of things start happening. You don’t hardly know the place when you get back.”

“Yeah, there’s a few things that have changed, I guess.” Leighton stuck his hands in his pockets. “I imagine you know A. L. Gunnels passed on.”

“No, I hadn’t heard that. Who’s the new mayor?”

“The truth is, you’re looking at him.”

This was the moment Tandy had dreaded, the worst thing about coming back. At two o’clock this morning, as he sat on a hard bench at the depot, batting away mosquitoes and doing his best to stay awake, he had imagined what it was going to feel like when he stood face-to-face with his brother and acknowledged another of Leighton’s successes, and it had almost been enough to make him jump on the next train leaving town. The problem was, he didn’t have the money to buy a ticket on the next train. He’d traveled just as far as he could.

“Well now, damn if we don’t have a politician in the family,” he said. “Congratulations.”

He offered Leighton his hand. When his brother took it, Tandy felt how puny his own fingers were. The handshake almost crushed them.

“All I plan to do’s serve out the rest of A.L.’s term. Some folks got together and asked me to do it, and I felt like I couldn’t say no. I don’t know if congratulations are in order, though. Maybe condolences would be more appropriate.”

“How come?”

“We’ve got some troublesome issues to confront. For instance, there’s a group of folks who want to pass an ordinance making it illegal to construct any more frame buildings, because they’re scared a fire’ll sweep through and burn the whole town down. But brick’s expensive, so some folks are claiming this ordinance’ll discourage new businesses and retard progress—retard progress is a phrase you hear in the board meetings every two or three minutes. People get all heated up over stuff like that, and by virtue of being both mayor and editor of the local paper, I’m smack-dab in the middle.”

If being smack-dab in the middle displeased him, Tandy couldn’t tell it. Leighton seemed, as always, quite happy with himself.

He did not, however, look particularly happy with Tandy. He let his eyes travel down his brother’s torso to his pants, which a year ago had been white but were now a dingy cream color, with spots of mud and dried blood on the knees. The boots had last been shined five or six months back and were in need of repair.

“What happened?” he said. “Somebody catch you dealing from the bottom of the deck?”

“Nobody does that anymore.”

“Well, it looks like somebody caught you doing something.”

Nobody had caught him doing anything. A little more than a week ago, he’d been in a game where the pot had reached six thousand dollars, and a fellow he’d never seen before, a wiry little man with a funny accent and a gold watch chain that had a miniature jockey’s cap and a saddle hanging from it, had convinced him and the other three players to follow him over to the bank, where he’d request a loan based on his hand. Tandy had bought the key to the deck, he held a strong hand, and it never crossed his mind, not for one minute, that one of the other players might have bought the key, too. He believed he’d found the perfect sucker. He believed it right up until the man with the watch chain—having received his loan from a banker who Tandy figured must not know the first thing about poker—played a king and four aces.

The money hadn’t been Tandy’s to lose. People wanted that money, believing it was theirs, and if you looked at things in a certain way, they were right. He’d heard that if he didn’t leave town, somebody might kill him.

“You’re broke, aren’t you?” Leighton said.

“Temporarily insolvent’s how I’d put it.”

“Temporary’s got its limits. After a while, temporary becomes permanent.”

“There was a three-day period six months ago when I could have bought you and everything you call yours.”

“No,” Leighton said, “you couldn’t have.”

For a moment, while Leighton stood there facing him, letting his words sink in, Tandy hated his brother. It wasn’t the first time, nor would it be the last. But he knew that if he could just keep a grip on himself for a few more seconds, the moment of hating would pass and he’d be left with the same old bunch of feelings, which were far too complicated to bear a single name.

Leighton turned, walked back over to his desk. He flipped open a ledger that lay near his typewriter. He made a show of staring at it, running his finger down the page as if he were checking figures. “Where are you staying?”

“Thought I’d take a room at Miss Rosa’s.”

“Room and board at Miss Rosa’s is about four dollars a week. I imagine you’re a few dollars short?”

Tandy was tired: he hadn’t slept for two days or had a drink for three, and all he really wanted was to get into a nice soft bed with a bottle of whiskey and drink till he passed out cold. But one thing you could always do when you couldn’t do anything better was bluff. If nothing else, it kept you in the game. So he did his best to sound rakish, untroubled.

“Briefly.”

Leighton opened a desk drawer and took out a metal box. He raised the lid, pulled a few bills out, counted and laid them on the desk, then put the box back in the drawer. The entire operation probably took only a minute or so, but to Tandy it felt like ten years.

Leighton picked up the stack of bills and walked over and handed them to him.

“Thanks,” Tandy said.

“Sarah and Will’ll want to see you. Why don’t you come over tonight and eat supper?”

“All right.” He crammed the bills into his pocket. “Leighton . . . that board you mentioned? Has it got the power to give out jobs?”

“Jobs?” Leighton said, sounding as if he couldn’t believe he’d heard right.

“You know. City jobs.”

“Yeah,” Leighton said. “It’s got the power to hire folks to sweep up the marshal’s office and cart garbage over to the town dump. You want to cart garbage, Tandy? Is that what you’re saying?”

Beneath Tandy’s feet, the floorboards creaked. He was sweating now. He smelled his own odor.

Through the inverted letters on the front window, Leighton watched his brother shamble across the intersection at Main and First, his head down, his eyes on the ground. He looked whipped, the very picture of failure and dejection, until he heard the sound of a horse’s hooves and looked up. Sally Stark, the wife of a local planter, was driving along in a carriage. Instantly, Tandy’s bearing changed. Straightening himself up to his full height, he doffed his fedora and swept it through the air, then executed a graceful bow.

Sally Stark pulled back on the reins, and the horse slowed down. Leighton watched while her face broke into a smile. Her lips formed a single word.

Tandy!

The house stood on the banks of Loring Bayou.A big white house surrounded by a white picket fence, it had a broad veranda overhung by cedars, pecan trees and locusts. Leighton had designed it himself, in concert with his father-in-law, and it had cost him $2,500. Tonight, it was brightly lit.

Walking up from the street, he heard music: Sarah playing the piano, Tandy singing “Danny Boy.” For a moment, he stopped and listened. He’d always loved hearing Tandy sing, but if he was in the room while the singing was going on, Leighton had to shut his eyes to enjoy it. Seeing the man behind the voice ruined the effect.

They had just finished the final chorus when he opened the door. Tandy was clean now, his pants and jacket sparkling white, his boots shining in the lamplight, though they still looked a little worn around the toes. He’d shaved and waxed his mustache and combed his hair.

He stood beside the piano. Sarah’s cheeks were rosy, and she was smiling up at him. Upstairs, in a walnut cabinet near the bed, there was a photograph of her sitting beside Tandy in a buggy. In the picture, she wore a lace dress and a tall hat with taffeta trim, and she was looking at him with that same bright smile on display.

Tandy was at home among women, always able to make them smile, whereas Leighton never quite felt comfortable in their presence. He liked them and wanted to be around them, but whenever they were near, he became aware of his size. He tended to bend toward them, ducking his head in compensation. More often than not, they instinctively pulled away.

“That sounded pretty darn good,” he said. He removed his hat, hung it on the rack and walked over and laid his hand on Sarah’s shoulder. “Maybe y’all could go on the road and make some money.”

“Tandy can’t make money. It’s beneath him.”

“Well, I wouldn’t say it’s beneath me. I’d say it’s somewhere off to the side.”

“It seems there are some people in New Orleans to whom Tandy owes more than six thousand dollars.”

“Give or take a dollar or two.”

“And they’ve suggested he might come to harm.”

“They’re not bad folks. They’re just a little too quick to rile.”

“So Tandy is here, as it were, in hiding.”

She hadn’t looked at Leighton since he’d walked in. He willed himself now to lift his hand from her shoulder, but he couldn’t. She was wearing a voile frock so sheer his fingertips could feel her pulse through the fabric. He felt the heat of her body as well, and something else—moisture, the sheen of perspiration on her skin. His free hand rose as if of its own volition; he almost laid it on her other shoulder and caressed her. What stopped him was the sight of a blackish smear on his palm. His hands had always looked rough, and now they frequently bore ink stains. He could never quite get them all off.

“Tandy can’t hide,” he said. “Tandy draws crowds like a dog draws fleas.”

They sat at the supper table, lingering over the remains of an apple pie Sarah had baked that afternoon. Tandy was telling a story about his adventures in New Orleans.

“So the driver, he looks over his shoulder at me and says, ‘The one on the left, sir, he rough-gaited, and the one on the right, well, she a shirker. This crushed gravel on the street, it get up in the frog on the horse’s foot, and it can make ’em go lame. Well, the one on the right there, she know I know that, so she start acting like that what’s done happened. But there’s one other thing she know I know. She know I know her just as well as she know me.’ And you know what the driver did then?”

“No,” Will said. “What’d he do, Uncle Tandy?”

“Well, he pulled the whip out of the socket and whacked the mare on her tail. But instead of picking up her pace, she got her tail up over the dashboard and cut loose with about five or six pounds of the stinky stuff.”

Will burst out laughing.

“Tandy!” Sarah said.

“The old nigger was naturally the color of blackstrap molasses, but when the horse did that, he gagged and turned green. He had to pull his hat off and hold it over his face all the way back to Jackson Square. Tell you the truth, it like to killed me, too.”

“Yeah,” Leighton said. “It just about killed me now to listen to it.”

He glanced at Will. He was nine, a tall skinny boy who sometimes got so excited he forgot to eat. He also forgot to sleep.

“It’s about time for you to go to bed, son.”

“Daddy!” Will balled his hands up into fists.

“William Lee Payne,” Sarah said. “Can you imagine your father or your uncle behaving like that if their father had told them to go to bed?”

Face sullen, Will kissed Sarah good night, then walked over and leaned against Leighton.

“Good night, son.”

“Night.”

On his way out, he paused long enough to shake hands with Tandy. “You’ll still be here tomorrow?”

“For tomorrow and for many days to come.”

“And you’ll tell me some more stories?”

Tandy leaned back in his chair. Light glinted off the buttons on his jacket. “I’ll tell you stories,” he said, “that’ll make hair spring up in your armpits.” He grabbed Will and tickled him under the arms, and Will shrieked and ran for the stairs.

Tandy watched him race up them two at a time. “He’s going to be a big one.”

“Well, there aren’t any small ones in our family.”

“I’m the runt of the litter.”

“It wasn’t a very big litter to be the runt of,” Sarah said.

“It was litter enough. Sometimes, when I was sitting at the table like this, across from Leighton and Daddy, I felt like I lived among giants.”

“Oh, come on. Till I was fourteen or fifteen, you were just as tall as I was.”

“I felt like I lived among giants. A war hero for a father and a brother who was clearly destined for the greater walks of life. And now, in addition to being a man of letters, he’s the mayor.”

“Yeah, and these civic posts are highly distinguished. That’s why last year we reduced the membership on the Board of Aldermen from five to four. Couldn’t convince a fifth man to run.”

“Speaking of civics,” Tandy said, “what else is new around town? Old Percy Stancill still buying up every piece of land he can?”

“Owns upwards of ten thousand acres.”

“Didn’t his wife pass on?”

“Two wives passed on. He’s on the third one now.”

“Good for him.”

“You probably noticed the hitching posts along Main,” Sarah said. “Now it’s illegal to tether the beasts to porch columns. And Rosenthal’s sells ice. They bring it up the river on a boat, and he stores it in sawdust. Oh, and we have a Negro serving as postmistress.”

You could tell, knowing Tandy, when something aroused his interest. If he was sitting at a table, he would place both hands palm-down before him, as if he meant to push himself up. The hands were out there now. “A colored postmistress?” he said. “How and when did that come about?”

Leighton picked up his coffee cup and glanced at Sarah.

She said, “I’ll get some more.”

He waited until she’d left the dining room. “The postmistress got the appointment during McKinley’s first term,” he said. “I think Jim Hill recommended her.”

“One of ’em scratching another one’s back.”

“Well, somebody’s always scratching somebody’s back, Tandy. I reckon colored folks itch from time to time, same as we do.”

“Yeah,” Tandy said, “I guess so. So who is she—this postmistress?”

Leighton lifted his fork and picked at the remains of his pie. “Actually, you know her.”

He looked up just as the light went on in his brother’s eyes.

Wearing her carpenter’s apron, she moved down the row, pulling those speckled butter beans off the vines and dropping them into her pockets. She’d planted late this year, toward the end of April. Now the garden was full of beans and squash, cucumbers and tomatoes. The cantaloupes weren’t looking too good, but you couldn’t have everything. She had plenty.

The garden was hers: she’d laid the rows out, erected oak posts at the ends of her bean patch, strung wire between them and tied saplings to the wire with rag string; she’d sown in springtime and hoed on June days so hot she almost swooned. Seaborn P. Jackson was nothing if not industrious, but he would not lift a finger to plant or tend a garden. Dirt, as far as he was concerned, was a substance to stand on. He derived no pleasure from its presence on his hands.

First thing each morning, he heated water for washing. In the back room, behind a gray curtain, he stood in the washtub and bathed himself meticulously, his bald head visible above the curtain rod. Then he shaved and brushed his teeth with baking soda, and once he was finished, he donned his suit and tie. He would not appear at the breakfast table until fully dressed for business.

He sold insurance—health, life and burial, mostly burial—for the Independent Life Insurance Company. For no more than twenty cents a week, you could assure yourself a hundred-dollar funeral. Seaborn himself oversaw the proceedings and was fond of stating he’d never let a dead person down. People called him “the policy man.” Behind his back they called him “a biggity nigger,” or just “Biggity.”

She walked over to the back porch and emptied the beans into a pan, then carried it inside. She was sweating now, her legs and back and armpits wet. She went out back and, after scanning the shrubs lining the rear of the yard, she pulled her blouse off. She primed the pitcher pump, then began sloshing cool water on her arms and her belly, her shoulders and breasts. Seaborn had warned her never to do this. A white man had stopped him on the street one day right in front of Rosenthal’s and told him that his son and one other boy had been walking by one day and noticed his wife out back with her shirt off.

“It’s fine for y’all to live where you live,” the man had said, “but there’s a certain amount of responsibility that goes with the ground.”

The only way the man’s son and the other boy could have noticed her with her top off would have been to squat and peer in through the bushes, and while Seaborn surely knew that, he just as surely never said it.

“Don’t sir ’em,” she’d once heard him advise a young man of their acquaintance. “Suh ’em. There are sounds we can make which cause them discomfort, and an r on the end of the word sir is one of them. Say uhh after sss. Lay down hard on that last syllable, draw it out, make that good lasting impression, and they won’t notice you again for three or four months.”

So Seaborn would have rolled his eyes, nodding his head at this word to the wise, then come down hard on that last syllable. “Yes, suh.” The man would quit noticing him, though he and his son and his son’s friend would keep right on noticing her.

. . .

The post office stood directly across the street from Rosenthal’s, in between the Bank of Loring and Farmer’s Drugstore. This morning, when she got there, a mail sack was propped against the door. Sometimes the train came a few minutes early, and even though she’d asked the man who drove the wagon for the C & G not to leave the mail standing out front, where just anybody could take it, he was white and did as he pleased.

She unlocked the door, then grabbed the sack by its drawstring. She spent the next half hour distributing the mail, popping envelopes into boxes, bending over and glancing through the little windows from time to time to make sure nobody had entered the lobby without her hearing them. To keep customers waiting was not her policy. She’d even installed a telephone at her own expense so people could call and find out if they had any mail.

She’d just finished putting the mail out when the front door creaked open. She grabbed a rag and wiped the ink off her hands, then straightened her hair and walked out to the counter.

It was Blueford. He had his hands in his pockets and was wearing the funny-looking little tricornered white hat Rosenthal insisted on during business hours. The hat would’ve looked ridiculous on most men—she could scarcely imagine it atop Seaborn’s bald pate—but somehow Blueford always bore it with dignity, even when he had a fifty-pound sack of cornmeal balanced on his shoulder.

“What you doin’ this morning, Loda?”

“Same as every morning.”

“Mail done come yet?”

“Sure has.”

“I don’t reckon I got nothing from my auntie, did I?”

She kept the mail for general delivery stacked on a shelf behind the counter. There was only a handful of items today. She went through them quickly, finding nothing for Blueford. “Sorry. I hope it wasn’t money you were expecting.”

“Not hardly. She done supposed to had a picture made of my cousin’s little baby. I ain’t never yet seen him.”

“Is this the aunt that lives in Vicksburg?”

“Aunt Florice. Only one I got. Only natural aunt, anyway. Least as far as I know.”

He must have noticed that her gaze had shifted, that she was looking beyond him, at the street. A couple wagons passed by, though no one was walking toward the post office. Nonetheless, he did what he knew she needed him to do: he began to take his leave.

“Well,” he said, “old Rosenthal got twenty thousand things he expect me to do in the next twenty minutes.”

He smiled at her and walked over to the door. He watched the street for a moment. Then, as if it were an afterthought—which it was not, because Blueford never entertained afterthoughts—he said, “By the way. Guess who I just saw this morning?”

“Who?”

“That younger one.”

“Oh,” she said. “So he’s back.”

“Yeah.” He opened the door. “Reckon wherever he was at, they must of done run out of trouble.”

Trouble.

She worried about it—you always had to—though she hadn’t seen much of it in a pretty good while. She was not the only Negro in Mississippi with a government appointment, but she was the only one in Loring. Add to that the fact she and Seaborn lived a few yards north of the railroad tracks and owned a twenty percent interest in Rosenthal’s, and you became somebody folks couldn’t help but pay attention to.

At dusk she closed the office, stepped around the corner at Main and First on her way home, and ran right into a white man, her head actually striking his chest. She bounced back and was about to apologize when she saw who it was.

“Oh, Loda,” he said. “I’m sorry. I should’ve been watching where I was going.”

“No,” she said. “It’s my fault.”

“I didn’t hurt you, did I?”

The truth was, her nose stung pretty good. “No,” she said. Then: “Excuse me. No sir.”

“Don’t do that. Please.”

She was looking up into his face. She could see his features distinctly: the square chin, the perfectly shaped nose, the powder blue eyes. He’d recently cut himself shaving; there was a nick near one corner of his mouth.

“It looks to me,” she said, “like your daddy could’ve done a better job teaching you to use a razor.” She stood back to observe her last word’s effect: averted eyes, a faint bobbing of his Adam’s apple, nothing more.

“I hear your brother’s back in town,” she said, then walked on.

Recenzii

“A powerful tale . . . a skillful interweaving of complicated relationships to family and history.” –The Washington Post Book World

“A compelling look at moral courage. . . . The place, events, and emotions are so authentic, it’s hard to believe the story is fiction.” –USA Today

“Invites comparison with Faulkner’s greatest novels.” –The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

“Perceptive, finely wrought . . . captures post-Reconstruction Mississippi, caught between the promise of progress and a lament for the antebellum order.” –Vogue

“A compelling look at moral courage. . . . The place, events, and emotions are so authentic, it’s hard to believe the story is fiction.” –USA Today

“Invites comparison with Faulkner’s greatest novels.” –The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

“Perceptive, finely wrought . . . captures post-Reconstruction Mississippi, caught between the promise of progress and a lament for the antebellum order.” –Vogue

Descriere

A heart-stopping story, written with grace and lucidity, located at the dead center of Southern mythology and an intransigent national trauma. In a small community deep in the Mississippi Delta, black and white alike struggle to coexist as the era of Reconstruction gives way to Jim Crow.