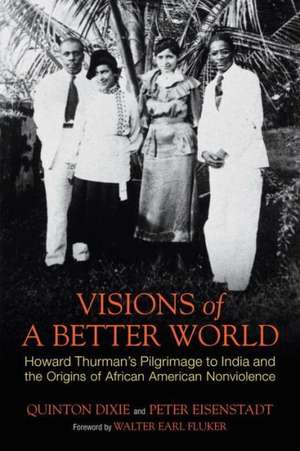

Visions of a Better World: Howard Thurman's Pilgrimage to India and the Origins of African American Nonviolence

Autor Quinton Dixie, Peter Eisenstadten Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 oct 2014

When Thurman (1899ߝ1981) became the first African American to meet with Mahatma Gandhi, he found himself called upon to create a new version of American Christianity, one that eschewed self-imposed racial and religious boundaries, and equipped itself to confront the enormous social injustices that plagued the United States during this period. Gandhi’s philosophy and practice of satyagraha, or “soul force,” would have a momentous impact on Thurman, showing him the effectiveness of nonviolent resistance.

After the journey to India, Thurman’s distinctly American translation of satyagraha into a Black Christian context became one of the key inspirations for the civil rights movement, fulfilling Gandhi’s prescient words that “it may be through the Negroes that the unadulterated message of nonviolence will be delivered to the world.” Thurman went on to found one of the first explicitly interracial congregations in the United States and to deeply influence an entire generation of black ministers—among them Martin Luther King Jr.

Visions of a Better World depicts a visionary leader at a transformative moment in his life. Drawing from previously untapped archival material and obscurely published works, Quinton Dixie and Peter Eisenstadt explore, for the first time, Thurman’s development into a towering theologian who would profoundly affect American Christianity—and American history.

Preț: 170.14 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 255

Preț estimativ în valută:

32.56€ • 33.87$ • 26.88£

32.56€ • 33.87$ • 26.88£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 14-28 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780807001721

ISBN-10: 0807001724

Pagini: 272

Dimensiuni: 152 x 226 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.36 kg

Editura: Beacon Press (MA)

ISBN-10: 0807001724

Pagini: 272

Dimensiuni: 152 x 226 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.36 kg

Editura: Beacon Press (MA)

Notă biografică

Quinton Dixie and Peter Eisenstadt are two of the country's leading experts on Howard Thurman. They are both senior volume editors of the Howard Thurman Papers Project and have extensive backgrounds in African American history and religious history. Dixie is assistant professor of religious studies at Indiana University-Purdue University at Fort Wayne. He holds MA and PhD degrees in religious studies and American church history, respectively, from Union Theological Seminary. He is coauthor, with Juan Williams, of This Far by Faith, and is coeditor, with Cornel West, of The Courage to Hope. Eisenstadt is an independent historian with a PhD in history from New York University. He is the author or editor of six books, including Rochdale Village, Encyclopedia of African American Culture and History, and Black Conservatism. He is also the associate editor of The Papers of Howard Washington Thurman, Vols. I-III.

Extras

Introduction

Long before the two men met, long before he had any inkling that a meeting would ever be possible, Howard Thurman had been preparing for an encounter with Mohandas K. (Mahatma) Gandhi. When the meeting took place, in early 1936, Thurman and his colleagues would be the first African Americans to meet with the famous leader of the Indian independence movement. Thurman’s time in India was less a transformation than a confirmation of what had long been his core belief: Christianity, as it had been traditionally practiced, was incapable of taking on the greatest challenge of the day, social and racial inequality. Howard Thurman was never a firebrand, and to some, who did not pay close attention to his message, he seemed to be an otherworldly mystic with little time to spare for any down-to-earth realities, including the practical politics of American minorities fighting for their civil rights. But for those who listened carefully, including many in the rising generation of African American leaders in the 1930s and 1940s, among them James Farmer, Pauli Murray, and Martin Luther King Jr., they heard a call for a new Christianity—one without dogmas, dedicated to the principles of pacifism and nonviolence, and utterly committed to the task of eradicating Jim Crow in all its varieties and manifestations. It is true that Thurman was never primarily a writer or speaker on political topics. But in his public appearances, articles, and teaching in the 1930s and 1940s, and both in his own right and through his broader contagion, he was one of the creators of a distinctly African American path to radical Christian nonviolence.

On October 21, 1935, Howard Thurman reached Ceylon’s major port and capital city, Colombo. When Thurman arrived in Colombo he had been traveling by rail and boat for a month, since he and his party had left New York Harbor. He was in Ceylon as chair of the four-person Negro Delegation, undertaking a “Pilgrimage of Friendship” to South Asia on the behest of the Student Christian Movement in the United States (basically an alliance between the YMCA and the YWCA), and its Asian counterpart, the Student Christian Movement of India, Ceylon, and Burma. He was accompanied by the other members of the delegation: his wife, Sue Bailey Thurman, and another couple, Edward and Phenola Carroll. The delegation would remain in South Asia for a hectic four months, crisscrossing India (including stops in what is now Pakistan) and visiting Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) and Burma (now Myanmar). Their path would take them from the subtropical waters of the Indian Ocean to the wintry foothills of the Himalayas, from the Khyber Pass on the Indian border with Afghanistan to the Irrawaddy Delta in Southeast Asia. They would visit fifty cities, and Thurman, who took the lion’s share of the speaking engagements, would make at least 135 appearances, on occasions ranging from small, intimate gatherings to mass meetings. They would meet with thousands of people, among them the two most famous Indians of the time. In his ashram (which doubled as one of India’s most distinguished institutes of higher learning) the delegation would meet with the poet and educator Rabindranath Tagore. And early one morning in a little town in outside Bombay, they would become the first African Americans to meet with Mahatma Gandhi, who, at the end of their meeting, imparted the famous message that “it may be through the Negroes that the unadulterated message of nonviolence will be delivered to the world.” The time Thurman spent in India would be a turning point in his life and a watershed in the gathering struggle of African Americans for racial equality.

At the time of his arrival in Ceylon, Thurman was thirty-five years old. He was an ordained Baptist minister and a professor of religion at Howard University, where he led the weekly services at Howard’s Rankin Chapel. If Thurman was, as one of the organizers of the Pilgrimage of Friendship remarked, somewhat long in the tooth to be a “student” Christian, there was no doubt that he was already acclaimed as one of the leading young ministers of his generation and a man who had already amassed a considerable reputation as a preacher and religious thinker, before audiences both white and black. He was, the organizers of the Negro Delegation thought, the perfect person to bring the message of American Christianity to India.

The delegation was in India at the request of the head of the Student Christian Movement in India, Ceylon, and Burma: Augustine Ralla Ram. Ralla Ram had wanted a delegation of Negroes to visit because he felt they could relate better and would be more fully accepted than the white missionaries who comprised the vast majority of the overseas Christians coming to India. Unlike most of their predecessors, the Negro Delegation was not coming to India as evangelists, as would-be savers of souls, or as bringers of Christ to India. (Thurman found it typical of Western pretensions that most missionaries ignored the fact that Christianity had been in India since about the third century ce, long before any Angles or Saxons had adopted the new faith.) Rather than proselytize or in any conventional way preach the gospel, the Negro Delegation was in Asia to represent one version, their version, of African American Christianity to an Asian audience and to present the complexities of being black and Christian in 1930s America. How this would be received, how the members of the Negro Delegation would meet or disappoint expectations, they were about to find out.

The first moments in Ceylon were not promising, as the delegation had their initial tangle with British officialdom. The customs officials wanted to hold on to their passports until they provided the address at which they would be staying in Colombo (which they didn’t know) and until they were met by their local hosts (which Thurman, not very impressed with the competence of the committee in New York City that had made the arrangements, did not think would happen in a timely fashion). But they were eventually met by a local committee, and, passports in hand, were allowed to disembark. “With this,” Thurman noted with some relief in his journal, “I turned away ending my first contact with B.G. [British Government].” It would be the first of many. Thurman was warned the next day, before their initial press conference—and they had been coached on this point long before they left the United States—“Do not say anything to offend the white man lest our journey be cut off before it started.” The delegation had developed careful rules about what to say and where to say it, with the certainty (at times confirmed) that they were under a constant, if generally discreet, surveillance.

But what was most striking about Colombo was how un-British it was. Once in Colombo, Thurman would write in his autobiography, he entered “a totally new world.” He was entranced by the “strangeness of the dress, the unfamiliar language,” the new smells and the new food, which he found uncomfortably spicy. Although the tour was planned to coincide with the end of the summer monsoons and the coolest months of the year, the climate remained humid and the weather subtropical. Thurman was a scion of the pre-air-conditioned South, but he nonetheless found Ceylon’s weather so “enervating” that it “took an act of will” for him to “prepare for the day.” He learned to start every day by carefully unwrapping his mosquito netting and gingerly watching his footfalls lest he step on an unsuspecting scorpion or cobra. (He also, like many new visitors to Asia from the United States, had to experiment with the squat privies, which he deemed “a much more rational and natural arrangement” than the American toilet.)

But above all he was fascinated by the Ceylonese. Everyone around him had dark skin, some as dark as his own deep-brown complexion. “The dominant complexions all around were shades of brown, from light to very dark.” All around “were the many unmistakable signs that this was their country, their land. The Britishers, despite their authority, were outsiders.” And yet they ruled the country. This was the paradox of imperialism. For all their power, the British would always remain outsiders and unwanted intruders. And for all their powerlessness, the native inhabitants of Ceylon knew it was their country.

Thurman’s perception of the complexities of racial difference, always acute, was heightened during his time in Asia, because he knew he was dealing with a racial world both like and unlike that with which he was familiar. It was unfamiliar in that Thurman suddenly had vaulted to the top of the racial hierarchy, with all the privileges accorded Europeans and other Westerners in British Asia: first-class train compartments, entrance to European-only waiting rooms, and a servile class to attend to his comforts. And of course it was familiar because there were the usual vast differences between the powerful and the powerless, with the gulf, if anything, wider than what he was used to at home. He found this very strange and uncomfortable. He found the Europeans on the whole to have a profound disregard for the personality of native people. “Servants were everywhere” and everywhere degraded, he wrote in his Colombo journal. He remembered having dinner with an eminent academic in Colombo, who “was making a crucial point to me and was frustrated because he had to pay attention to boning the fish on his plate. In disgust he put down his fork and fish knife and yelled, ‘Boy—come bone this fish!’ Shades of the United States.”

What was also familiar to Thurman was the experience of some whites not quite hearing what he had to say. He started his first full day in Colombo being interviewed by local reporters, and, following the warnings against opining on local politics, he spoke instead on conditions in the United States. He was rather upset with the result, feeling the main topic of concern to the local press was the boxer Joe Louis and his supposedly comical gormandizing and sartorial style. Thurman tried to convey a sense of the ferment rippling through contemporary black America, and he was dismayed that the reporters were primarily interested in blacks who seemed to embody fading ideals of racial subservience and deference. “They wanted to know about Negroes who had achieved things in life—I mentioned several but true to the mentality of the white world they did mention only Booker T. [Washington] & [George Washington] Carver.”

Although being for the first time in his life in a place where people of color were the overwhelming majority was remarkable, perhaps the most novel aspect of Colombo for Thurman was that he was in a country where Christianity was not the dominant religion. Thurman would spend much of the next four months comparing Christianity with the three great religions that dominated South Asia: Buddhism, Hinduism, and Islam. The comparisons were often not flattering to Christianity. That first morning he was taken to see Buddhist and Hindu temples and an old Dutch church. He was impressed by the Buddhist temple, and the Hindu building “was not very clean but there was present a strange kind of serenity.” The Dutch church, on the other hand, “was severe, stolid, cold” and did not “stir a single emotion related to worship or religion in my own mind or heart.” At the local branch of the Student Christian Movement he heard a lecture by a local minister on Christianity in Ceylon—“of course he meant Protestant Christianity”—which struck Thurman as narrowly European in its condescension to the native population, and Thurman was “not impressed with him or with what he said.”

If anything Thurman was even more upset by a worship service led by a native Ceylonese student at the YMCA. “He was Pentecostal in his emphasis and said that the second coming of Christ was universal because he had come in fulfillment of the word, thus before the end of time the gospel would be preached to all people. It was a wretched disappointment and I saw trouble ahead if there were many like him ahead. I appreciated his seriousness but it was all so sad because he had been completely duped.” Thurman’s first days in Colombo were spent observing the limitations of official Christianity in Asia, an exotic implant that seemed jarringly out of place, and an institution used by European and natives alike not as a means to greater spiritual insight but as a crutch for unexamined dogmatism. “On the whole,” Thurman wrote, with experience of official Christianity in mind, “the days in Colombo were not very satisfying.”

Perhaps not, but they were certainly very interesting, and the most memorable moment occurred almost at the beginning of his stay, probably on his first full night in Asia, when Thurman was asked to speak before a meeting of the law students at the University of Colombo. His encounter that evening would be the most vivid of his meetings in Colombo, and in some ways it would provide the framework for the remainder of his time in Asia, and indeed, in many ways, for the rest of his career. There probably was no single incident in his life that Thurman would write or speak about more frequently than his conversation that evening with an anonymous Ceylonese lawyer. He first did so less than a week after it happened while the delegation was still in Colombo.

Although in his many tellings of this tale he would elaborate it differently each time, the basic story always remained the same. Thurman had been asked to speak on “aspects of the Racial Parity in America.” As a rule, Thurman did not speak about race relations, at least in such bald sociological terms. It was not, he felt, what he did best, and Thurman found it faintly patronizing that race seemed to be the only topic that whites wanted to hear blacks speak about, as if they were fit to speak on nothing else but some aspect of the “Negro Question.” For Thurman, to speak about race before predominantly white audiences perhaps smacked too much of the hypocrisies of a revival meeting, the preacher ritually invoking the hellfire and brimstone of racial oppression, the cowed listeners making skin-deep and insincere confessions of sins before quickly returning to their old ways.

But in October 1935, Thurman was of course not addressing white audiences in the United States but Asians in Ceylon who were genuinely interested in getting accurate information about race in the United States and were not complicit in the system of racial discrimination they were asking Thurman to discuss. Despite his professions of being incapable of giving talks on current affairs, the sort filled with statistics and acute political observations, Thurman was a very close student of all aspects of American race relations and had prepared extensively for just such meetings before going to India, intensely studying race and politics in both America and Asia and speaking to many experts in the field. He probably gave more explicitly political talks while in Asia than at any other time in his career.

The interest in Thurman’s talk at the Law Club at the University of Colombo was, he noted, “most keen,” and the attentive listening of the audience was followed by many pertinent and sharp questions. They asked Thurman if it made “any difference in race feeling on the part of white Americans when Negroes become Christians,” and they queried why the federal government was powerless to enforce the Fifteenth Amendment, guaranteeing all citizens the right to vote. Thurman was fascinated to discover that his audience “knew all about Scottsboro,” the international cause célèbre arising from nine teenage blacks arrested on spurious rape charges in Scottsboro, Alabama, in 1931. He was asked very specific questions about it, such as the implications of the recent U.S. Supreme Court case Norris v. Alabama, decided in the spring of 1935, which held that the systematic exclusion of African Americans from juries constituted a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.

When the hour was up Thurman was invited downstairs for some coffee and further discussion in a more informal setting. He was somewhat inconsistent about who had invited him, sometimes describing him as a law student, sometimes as a lawyer, and sometimes as principal of the law college. He is at times described as a Hindu, which might mean that he was a member of Ceylon’s Tamil minority in the predominantly Sinhalese and Buddhist city of Colombo. Whomever he was, he was certainly not a Christian, though he knew a lot about Christianity, in part, presumably, from it being force-fed him in the Christian schools that were just about the only way in British Asia for a native to receive a Western education.

He got right to the point. “What are you doing here?” he asked. Thurman, startled, asked him what he meant. He repeated the question. “What are you doing here?” He told Thurman that he knew about the publicity surrounding the Negro Delegation, and how it was a pilgrimage of friendship from the students of the United States to the students in India, Ceylon, and Burma. “But what, really,” he wanted to know, “are you doing here?”

He told Thurman that he hadn’t planned on speaking to him, assuming that it would be a waste of his time. He had thought that Thurman would be a mere mouthpiece, a flunkey and messenger boy for Western Christianity, and that his answers would be bland and evasive. But instead, Thurman seemed to be bright and politically aware, fully alert to the depth of the problem of racial oppression in the United States, and not to be offering any easy solutions. This only made it worse. “I think that an intelligent young man such as yourself, here in our country on a Christian enterprise, is a traitor to all of the darker peoples of the earth. How can you account for yourself being in this unfortunate and humiliating position?”

Long before the two men met, long before he had any inkling that a meeting would ever be possible, Howard Thurman had been preparing for an encounter with Mohandas K. (Mahatma) Gandhi. When the meeting took place, in early 1936, Thurman and his colleagues would be the first African Americans to meet with the famous leader of the Indian independence movement. Thurman’s time in India was less a transformation than a confirmation of what had long been his core belief: Christianity, as it had been traditionally practiced, was incapable of taking on the greatest challenge of the day, social and racial inequality. Howard Thurman was never a firebrand, and to some, who did not pay close attention to his message, he seemed to be an otherworldly mystic with little time to spare for any down-to-earth realities, including the practical politics of American minorities fighting for their civil rights. But for those who listened carefully, including many in the rising generation of African American leaders in the 1930s and 1940s, among them James Farmer, Pauli Murray, and Martin Luther King Jr., they heard a call for a new Christianity—one without dogmas, dedicated to the principles of pacifism and nonviolence, and utterly committed to the task of eradicating Jim Crow in all its varieties and manifestations. It is true that Thurman was never primarily a writer or speaker on political topics. But in his public appearances, articles, and teaching in the 1930s and 1940s, and both in his own right and through his broader contagion, he was one of the creators of a distinctly African American path to radical Christian nonviolence.

On October 21, 1935, Howard Thurman reached Ceylon’s major port and capital city, Colombo. When Thurman arrived in Colombo he had been traveling by rail and boat for a month, since he and his party had left New York Harbor. He was in Ceylon as chair of the four-person Negro Delegation, undertaking a “Pilgrimage of Friendship” to South Asia on the behest of the Student Christian Movement in the United States (basically an alliance between the YMCA and the YWCA), and its Asian counterpart, the Student Christian Movement of India, Ceylon, and Burma. He was accompanied by the other members of the delegation: his wife, Sue Bailey Thurman, and another couple, Edward and Phenola Carroll. The delegation would remain in South Asia for a hectic four months, crisscrossing India (including stops in what is now Pakistan) and visiting Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) and Burma (now Myanmar). Their path would take them from the subtropical waters of the Indian Ocean to the wintry foothills of the Himalayas, from the Khyber Pass on the Indian border with Afghanistan to the Irrawaddy Delta in Southeast Asia. They would visit fifty cities, and Thurman, who took the lion’s share of the speaking engagements, would make at least 135 appearances, on occasions ranging from small, intimate gatherings to mass meetings. They would meet with thousands of people, among them the two most famous Indians of the time. In his ashram (which doubled as one of India’s most distinguished institutes of higher learning) the delegation would meet with the poet and educator Rabindranath Tagore. And early one morning in a little town in outside Bombay, they would become the first African Americans to meet with Mahatma Gandhi, who, at the end of their meeting, imparted the famous message that “it may be through the Negroes that the unadulterated message of nonviolence will be delivered to the world.” The time Thurman spent in India would be a turning point in his life and a watershed in the gathering struggle of African Americans for racial equality.

At the time of his arrival in Ceylon, Thurman was thirty-five years old. He was an ordained Baptist minister and a professor of religion at Howard University, where he led the weekly services at Howard’s Rankin Chapel. If Thurman was, as one of the organizers of the Pilgrimage of Friendship remarked, somewhat long in the tooth to be a “student” Christian, there was no doubt that he was already acclaimed as one of the leading young ministers of his generation and a man who had already amassed a considerable reputation as a preacher and religious thinker, before audiences both white and black. He was, the organizers of the Negro Delegation thought, the perfect person to bring the message of American Christianity to India.

The delegation was in India at the request of the head of the Student Christian Movement in India, Ceylon, and Burma: Augustine Ralla Ram. Ralla Ram had wanted a delegation of Negroes to visit because he felt they could relate better and would be more fully accepted than the white missionaries who comprised the vast majority of the overseas Christians coming to India. Unlike most of their predecessors, the Negro Delegation was not coming to India as evangelists, as would-be savers of souls, or as bringers of Christ to India. (Thurman found it typical of Western pretensions that most missionaries ignored the fact that Christianity had been in India since about the third century ce, long before any Angles or Saxons had adopted the new faith.) Rather than proselytize or in any conventional way preach the gospel, the Negro Delegation was in Asia to represent one version, their version, of African American Christianity to an Asian audience and to present the complexities of being black and Christian in 1930s America. How this would be received, how the members of the Negro Delegation would meet or disappoint expectations, they were about to find out.

The first moments in Ceylon were not promising, as the delegation had their initial tangle with British officialdom. The customs officials wanted to hold on to their passports until they provided the address at which they would be staying in Colombo (which they didn’t know) and until they were met by their local hosts (which Thurman, not very impressed with the competence of the committee in New York City that had made the arrangements, did not think would happen in a timely fashion). But they were eventually met by a local committee, and, passports in hand, were allowed to disembark. “With this,” Thurman noted with some relief in his journal, “I turned away ending my first contact with B.G. [British Government].” It would be the first of many. Thurman was warned the next day, before their initial press conference—and they had been coached on this point long before they left the United States—“Do not say anything to offend the white man lest our journey be cut off before it started.” The delegation had developed careful rules about what to say and where to say it, with the certainty (at times confirmed) that they were under a constant, if generally discreet, surveillance.

But what was most striking about Colombo was how un-British it was. Once in Colombo, Thurman would write in his autobiography, he entered “a totally new world.” He was entranced by the “strangeness of the dress, the unfamiliar language,” the new smells and the new food, which he found uncomfortably spicy. Although the tour was planned to coincide with the end of the summer monsoons and the coolest months of the year, the climate remained humid and the weather subtropical. Thurman was a scion of the pre-air-conditioned South, but he nonetheless found Ceylon’s weather so “enervating” that it “took an act of will” for him to “prepare for the day.” He learned to start every day by carefully unwrapping his mosquito netting and gingerly watching his footfalls lest he step on an unsuspecting scorpion or cobra. (He also, like many new visitors to Asia from the United States, had to experiment with the squat privies, which he deemed “a much more rational and natural arrangement” than the American toilet.)

But above all he was fascinated by the Ceylonese. Everyone around him had dark skin, some as dark as his own deep-brown complexion. “The dominant complexions all around were shades of brown, from light to very dark.” All around “were the many unmistakable signs that this was their country, their land. The Britishers, despite their authority, were outsiders.” And yet they ruled the country. This was the paradox of imperialism. For all their power, the British would always remain outsiders and unwanted intruders. And for all their powerlessness, the native inhabitants of Ceylon knew it was their country.

Thurman’s perception of the complexities of racial difference, always acute, was heightened during his time in Asia, because he knew he was dealing with a racial world both like and unlike that with which he was familiar. It was unfamiliar in that Thurman suddenly had vaulted to the top of the racial hierarchy, with all the privileges accorded Europeans and other Westerners in British Asia: first-class train compartments, entrance to European-only waiting rooms, and a servile class to attend to his comforts. And of course it was familiar because there were the usual vast differences between the powerful and the powerless, with the gulf, if anything, wider than what he was used to at home. He found this very strange and uncomfortable. He found the Europeans on the whole to have a profound disregard for the personality of native people. “Servants were everywhere” and everywhere degraded, he wrote in his Colombo journal. He remembered having dinner with an eminent academic in Colombo, who “was making a crucial point to me and was frustrated because he had to pay attention to boning the fish on his plate. In disgust he put down his fork and fish knife and yelled, ‘Boy—come bone this fish!’ Shades of the United States.”

What was also familiar to Thurman was the experience of some whites not quite hearing what he had to say. He started his first full day in Colombo being interviewed by local reporters, and, following the warnings against opining on local politics, he spoke instead on conditions in the United States. He was rather upset with the result, feeling the main topic of concern to the local press was the boxer Joe Louis and his supposedly comical gormandizing and sartorial style. Thurman tried to convey a sense of the ferment rippling through contemporary black America, and he was dismayed that the reporters were primarily interested in blacks who seemed to embody fading ideals of racial subservience and deference. “They wanted to know about Negroes who had achieved things in life—I mentioned several but true to the mentality of the white world they did mention only Booker T. [Washington] & [George Washington] Carver.”

Although being for the first time in his life in a place where people of color were the overwhelming majority was remarkable, perhaps the most novel aspect of Colombo for Thurman was that he was in a country where Christianity was not the dominant religion. Thurman would spend much of the next four months comparing Christianity with the three great religions that dominated South Asia: Buddhism, Hinduism, and Islam. The comparisons were often not flattering to Christianity. That first morning he was taken to see Buddhist and Hindu temples and an old Dutch church. He was impressed by the Buddhist temple, and the Hindu building “was not very clean but there was present a strange kind of serenity.” The Dutch church, on the other hand, “was severe, stolid, cold” and did not “stir a single emotion related to worship or religion in my own mind or heart.” At the local branch of the Student Christian Movement he heard a lecture by a local minister on Christianity in Ceylon—“of course he meant Protestant Christianity”—which struck Thurman as narrowly European in its condescension to the native population, and Thurman was “not impressed with him or with what he said.”

If anything Thurman was even more upset by a worship service led by a native Ceylonese student at the YMCA. “He was Pentecostal in his emphasis and said that the second coming of Christ was universal because he had come in fulfillment of the word, thus before the end of time the gospel would be preached to all people. It was a wretched disappointment and I saw trouble ahead if there were many like him ahead. I appreciated his seriousness but it was all so sad because he had been completely duped.” Thurman’s first days in Colombo were spent observing the limitations of official Christianity in Asia, an exotic implant that seemed jarringly out of place, and an institution used by European and natives alike not as a means to greater spiritual insight but as a crutch for unexamined dogmatism. “On the whole,” Thurman wrote, with experience of official Christianity in mind, “the days in Colombo were not very satisfying.”

Perhaps not, but they were certainly very interesting, and the most memorable moment occurred almost at the beginning of his stay, probably on his first full night in Asia, when Thurman was asked to speak before a meeting of the law students at the University of Colombo. His encounter that evening would be the most vivid of his meetings in Colombo, and in some ways it would provide the framework for the remainder of his time in Asia, and indeed, in many ways, for the rest of his career. There probably was no single incident in his life that Thurman would write or speak about more frequently than his conversation that evening with an anonymous Ceylonese lawyer. He first did so less than a week after it happened while the delegation was still in Colombo.

Although in his many tellings of this tale he would elaborate it differently each time, the basic story always remained the same. Thurman had been asked to speak on “aspects of the Racial Parity in America.” As a rule, Thurman did not speak about race relations, at least in such bald sociological terms. It was not, he felt, what he did best, and Thurman found it faintly patronizing that race seemed to be the only topic that whites wanted to hear blacks speak about, as if they were fit to speak on nothing else but some aspect of the “Negro Question.” For Thurman, to speak about race before predominantly white audiences perhaps smacked too much of the hypocrisies of a revival meeting, the preacher ritually invoking the hellfire and brimstone of racial oppression, the cowed listeners making skin-deep and insincere confessions of sins before quickly returning to their old ways.

But in October 1935, Thurman was of course not addressing white audiences in the United States but Asians in Ceylon who were genuinely interested in getting accurate information about race in the United States and were not complicit in the system of racial discrimination they were asking Thurman to discuss. Despite his professions of being incapable of giving talks on current affairs, the sort filled with statistics and acute political observations, Thurman was a very close student of all aspects of American race relations and had prepared extensively for just such meetings before going to India, intensely studying race and politics in both America and Asia and speaking to many experts in the field. He probably gave more explicitly political talks while in Asia than at any other time in his career.

The interest in Thurman’s talk at the Law Club at the University of Colombo was, he noted, “most keen,” and the attentive listening of the audience was followed by many pertinent and sharp questions. They asked Thurman if it made “any difference in race feeling on the part of white Americans when Negroes become Christians,” and they queried why the federal government was powerless to enforce the Fifteenth Amendment, guaranteeing all citizens the right to vote. Thurman was fascinated to discover that his audience “knew all about Scottsboro,” the international cause célèbre arising from nine teenage blacks arrested on spurious rape charges in Scottsboro, Alabama, in 1931. He was asked very specific questions about it, such as the implications of the recent U.S. Supreme Court case Norris v. Alabama, decided in the spring of 1935, which held that the systematic exclusion of African Americans from juries constituted a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.

When the hour was up Thurman was invited downstairs for some coffee and further discussion in a more informal setting. He was somewhat inconsistent about who had invited him, sometimes describing him as a law student, sometimes as a lawyer, and sometimes as principal of the law college. He is at times described as a Hindu, which might mean that he was a member of Ceylon’s Tamil minority in the predominantly Sinhalese and Buddhist city of Colombo. Whomever he was, he was certainly not a Christian, though he knew a lot about Christianity, in part, presumably, from it being force-fed him in the Christian schools that were just about the only way in British Asia for a native to receive a Western education.

He got right to the point. “What are you doing here?” he asked. Thurman, startled, asked him what he meant. He repeated the question. “What are you doing here?” He told Thurman that he knew about the publicity surrounding the Negro Delegation, and how it was a pilgrimage of friendship from the students of the United States to the students in India, Ceylon, and Burma. “But what, really,” he wanted to know, “are you doing here?”

He told Thurman that he hadn’t planned on speaking to him, assuming that it would be a waste of his time. He had thought that Thurman would be a mere mouthpiece, a flunkey and messenger boy for Western Christianity, and that his answers would be bland and evasive. But instead, Thurman seemed to be bright and politically aware, fully alert to the depth of the problem of racial oppression in the United States, and not to be offering any easy solutions. This only made it worse. “I think that an intelligent young man such as yourself, here in our country on a Christian enterprise, is a traitor to all of the darker peoples of the earth. How can you account for yourself being in this unfortunate and humiliating position?”

Recenzii

“Highly recommended.”—Choice