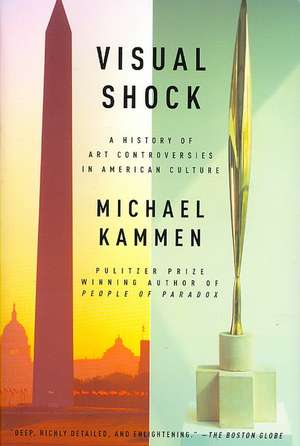

Visual Shock: A History of Art Controversies in American Culture

Autor Michael G. Kammenen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 oct 2007

Preț: 143.89 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 216

Preț estimativ în valută:

27.55€ • 28.74$ • 23.09£

27.55€ • 28.74$ • 23.09£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 19 februarie-05 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400034642

ISBN-10: 1400034647

Pagini: 450

Ilustrații: 69 HALFTONES

Dimensiuni: 133 x 204 x 26 mm

Greutate: 0.49 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 1400034647

Pagini: 450

Ilustrații: 69 HALFTONES

Dimensiuni: 133 x 204 x 26 mm

Greutate: 0.49 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Vintage Books USA

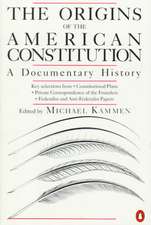

Notă biografică

Michael Kammen was born in Rochester in 1936. He took his BA at George Washington University and his PhD at Harvard. He is Newton C. Farr Professor of American History and Culture at Cornell University, where he has taught since 1965. A past President of the Organization of American Historians, he is the author or editor of numerous works and has lectured throughout the world. His People of Paradox was a Pulitzer Prize winner.

Extras

Chapter 1

Monuments, Memorials, and Americanism

Although the particulars have now grown hazy, older portions of the American public recall that the genesis of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in 1980–83 prompted considerable controversy. It seemed quite shocking at the time that the design competition could be won by a twenty-one-year-old architecture student. Even more provocative, because her plan seemed so austerely postmodern, it failed to fulfill customary notions of what a suitably heroic memorial should look like. Hence the harsh criticism that a "black gash of shame" actually dishonored those who had died in Southeast Asia (fig. 4). A mere list of names placed in a wide-angle pit, with a plaque referring only to an "era" rather than an actual war? Could the nation do no better?

Although H. Ross Perot had initially funded the design competition, he joined traditionalists in denouncing Maya Lin's winning entry and calling for a representational monument showing U.S. soldiers and an American flag. Secretary of the Interior James Watt, who had the power to veto the whole project, allowed it to go forward, but only on condition that a compensatory statue be commissioned and situated nearby (fig. 5). Watt forced his compromise on the federal Fine Arts Commission, which genuinely did not want to upstage Lin's design with what commission chairman and National Gallery of Art director J. Carter Brown called a "piece of schlock."

By 1983 the interchange between Maya Lin and Frederick Hart, the sculptor for the figural addition, served only to intensify ill-feelings underlying two conflicting visions of what might be the most appropriate ways to memorialize a massive number of deaths in an unpopular war. When asked her opinion of Hart's work, Lin candidly replied: "Three men standing there before the world-it's trite, it's a generalization, a simplification. Hart gives you an image-he's illustrating a book." Hart became even harsher when asked whether "realism" was the only way to reach the disaffected veterans and politicians.

The statue is just an awkward solution we came up with to save Lin's design. I think this whole thing is an art war. . . . The collision is all about the fact that Maya Lin's design is elitist and mine is populist. People say you can bring what you want to Lin's memorial. But I call that brown bag esthetics. I mean you better bring something, because there ain't nothing being served.

In the decades since those two interviews took place, Americans have voted with their feet, but more powerfully with their hearts and minds. Lin is a winner.

In 1987 Congress finally began its initial and pedestrian reaction to long-standing requests for a World War II memorial situated in a suitable place of honor in Washington, D.C. By the mid-1990s likely designs received a critical response for several reasons: first, they seemed too grandiose and therefore reminiscent of conservative monuments in Europe; second, they would likely obstruct the widely cherished two-mile vista between the U.S. Capitol and the Lincoln Memorial; and third, they would bisect the Mall by straddling its entire width. There were traditionalists on both sides of the issue: those who wished to preserve the uncluttered "purity" of the Mall and those eager to honor the "greatest generation" with a genuinely worthy plan consistent in merit with others in that coveted location. This conflict boiled up a full head of steam between 1997 and 2000, but Friedrich St. Florian's winning design finally received presidential approval when many pleaded that World War II veterans were rapidly dying and something should be completed before they had disappeared entirely (fig. 6).

Too few Americans are aware that most of the issues raised between 1980 and 2000 had been hashed out long before when initial plans were unveiled for the Washington Monument and the Lincoln and Jefferson memorials. Moreover, major statues meant to honor Washington and Lincoln had also aroused the most intense feelings on similar grounds: sheer size (gigantism), style (classical versus "modern"), location, and even nudity in the case of Horatio Greenough's seated George Washington, commissioned by Congress in 1833, completed in Florence, Italy, in 1839, and placed in the Capitol Rotunda in 1841. Scale, style, site, and apparel (or lack thereof) would become persistent and volatile issues in American art ever after. Monumental is a more neutral euphemism for gigantic and colossal, of course. Many artists, sculptors, and architects who we might find guilty of gigantism were only striving to do monumental work. Suitable scale seems to lie in the eye of the beholder yet also reveals the ambitious needs of a principal stakeholder.

Greenough's Washington touched off one of the earliest conflicts in the United States involving aesthetic criteria, and one of the most representative. A particularly problematic question involved style: how should the Father of His Country be depicted, as an idealized deity or as a revered native statesman? Classical or "American"? Godlike and spiritual or secular yet like-no-other? Greenough's solution turned out to be a hybrid: the head based upon Houdon's life mask certainly resembled Washington, but the body evoked Jupiter and Roman statuary (fig. 7). Hence the work got nicknamed George Jupiter Washington when it wasn't given more insulting designations. Greenough's inspiration was actually the Elean Zeus by Phidias, one of the greatest Greek sculptors, a work known only by description. Greenough was apparently seeking purity and simplicity rather than the pomposity that so many critics seemed to see in the statue. The snarls that ensued would demonstrate that compromise leaves almost no one satisfied.

Greenough's statue as well as Robert Mills's Washington Monument emerged in the wake of failed attempts to commemorate the centennial of the founder's birth by unearthing his body from Mount Vernon for reburial in the Capitol crypt in 1832. The cult of Washington as a superheroic if not immortal figure remained exceedingly strong, though strife persisted over the relative merits of his role as a symbol of national unity and his symptomatic value to southerners as a Virginia-based protochampion of states' rights. The Nullification Crisis early in the 1830s, prompted by South Carolina's threatened secession over tariff issues, added sectionalism to the mix of aesthetic differences and complicated them. Similarly it has long been forgotten that several significant sources of friction in the decade following 1911 involving the Lincoln Memorial arose from sectional tensions left unresolved by the Civil War. That monument, which is virtually devoid of references to slavery and the conflict it generated, was meant to serve as an emblem of national unification. The intertwined boughs of southern pine and northern laurel that gracefully encircle the frieze provide just one indication of that quest. (Because laurel is a symbol of victory, of course, the northern Republicans who called the shots enjoyed a not-so-subtle triumph.)

Serious debate would persist for more than a century following the 1820s: namely, whether monuments and architecture in the United States should pursue styles that feel native and new or should appropriate motifs from antique Greece and Rome. Horatio Greenough received interesting and revealing advice as he embarked upon his impassioned career as the premier American sculptor in the early republic. When he first attempted to model a figure of George Washington, he received wise counsel from a patron, the novelist James Fenimore Cooper: "Aim rather at the natural than the classical." That same heated issue would stay situated at the core of a decade-long quarrel over the most suitable design for the Lincoln Memorial. "Natural" meant more than avoiding stylistic imitation of the ancient world. It also meant having a heroic figure clothed in modern dress, and standing rather than seated like some emperor, Roman or Napoleonic.

Greenough got mixed signals, however, because his fellow New Englander Edward Everett advised him to "go to the utmost limit of size. . . . I want a colossal figure." That muscular word colossal and its synonyms would recur over and over again in intensely heated discussions about the Washington Monument, the Lincoln and Jefferson memorials, and the memorial for Franklin Delano Roosevelt finally unveiled in 1997. Midwestern opponents of the Lincoln Memorial design that ultimately prevailed (albeit scaled back in size owing to considerations of cost and weight) pleaded instead for a "colossal statue" of the man who saved the Union. But in 1969 William Walton, chairman of the Fine Arts Commission, epitomized more than a century of polemics when he wrote to the chairman of the FDR Memorial Commission, a member of Congress: "I urge that we get away from bigness as a manner of memorializing great men. A man's place in history is never determined by the size of his monument."

When Fenimore Cooper discovered the dimensions that Greenough had in mind, he considered them grandiose and advised his friend accordingly. The sculptor stuck with Everett's wishes, however, which reinforced his own aspiration, and designed a massive marble chair from which his seated Washington figuratively contemplated the ship of state he had brought into being. His gestures followed a classical formula seemingly well suited to a brand-new republic. Whereas Washington's right hand points heavenward, the source of law by which men live, the left hand returns his sword to the people because he has completed his service to them. It was not such a bad compromise, actually, between imperatives ancient and modern.

Skeptics scoffed that the oversize statue would not even be able to enter the Capitol for placement in the Rotunda. They were wrong, and initial responses to the monumental piece in 1841–42 seemed more favorable than not, though critics certainly made themselves known. When Greenough arrived from Florence in 1842 and saw how dim the Rotunda lighting was, however, he tried to have torches illuminate his work; but they only made matters worse. Flickering lights in a dim chamber do not enhance greatness. He then pleaded with Congress to move the monument out of doors so that it could be bathed in natural sunlight—a serious error, as it turned out—and that is when the harshest condemnations began to be heard. Maximum visibility only encouraged calumny.

Fierce blasts came from Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, who had offered stiffer warnings than Cooper's concerning size as well as nudity, and from Philip Hone, the former mayor of New York, who recorded the following in his diary:

It looks like a great herculean Warrier—like Venus of the bath, a grand Martial Magog—undraped, with a huge napkin lying on his lap and covering his lower extremities and he is preparing to perform his ablutions in the act of consigning his sword to the care of the attendant. . . . Washington was too prudent, and careful of his health, to expose himself thus in a climate so uncertain as ours, to say nothing of the indecency of such an exposure on which he was known to be exceedingly fastidious.

Nathaniel Hawthorne was pithier: "Did anyone ever see Washington naked? It is inconceivable. He had no nakedness, but I imagine was born with his clothes on and his hair powdered, and made a stately bow on his first appearance in the world." Being unclothed from the waist up was nude enough for the 1840s but particularly so for the Father of His Country, a man renowned for his dignified reserve as well as other self-possessed qualities. On this matter also, however, consensus could not be achieved. Ralph Waldo Emerson described the work as "simple & grand, nobly draped below & nobler nude above." He declared that it "greatly contents me. I was afraid it would be feeble but it is not." In many different ways and for numerous reasons, nudity would become a prime cause of controversy during the century and a half that followed.

Once it was determined that Washington would sit out of doors, exposed to extremes of weather and the uncontrollable excretions of birds, the figure became a prime target for pranksters. One inserted "a large 'plantation' cigar between the lips of pater patriae, while another had amused himself with writing some stanzas of poetry, in a style rather more popular than elegant, upon a prominent part of the body of the infant Hercules." Exactly which body part is unclear; but quite obviously political graffiti did not originate the day before yesterday. This monumental statue increasingly became an occasion for mockery, and Greenough's poignant letter to Robert Winthrop in 1847 sums up his frustration at having his motives and skills misunderstood by a nation so lacking in artistic sophistication.

A colossal statue of a man whose career makes an epoch in the world's history is an immense undertaking. To fail in it is only to prove that one is not as great in art as the hero himself was in life. Had my work shown a presumptuous opinion that I had an easy task before me—had it betrayed a yearning rather after the wages of art than the honest fame of it, I should have deserved the bitterest things that have been said of it and of me. But containing as it certainly must internal proof of being the utmost effort of my mind at the time it was wrought, its failure fell not on me but on those who called me to the task.

Washington's state of undress also made him appear pagan—not exactly proper in a society where evangelical Christianity enjoyed wide appeal. Although Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and many others praised it, the statue continued to inspire wags and scoffers throughout the remainder of the nineteenth century. The early rumor that it was too large to pass through the door of the Capitol gradually became a popular legend. Stories were repeated that it had to be moved outside because it threatened the very foundation of that big building and even that it sank the first ship that attempted to load it for "home" in Leghorn, Italy. The ultimate insult occurred in 1908 when Congress ordered that it be moved to the Smithsonian Institution's "Castle," ironic in turn because of Greenough's disdain for the Gothic style. A monumental mismatch of art and architecture.

During the later twentieth century, when certain works of public sculpture became crazily controversial, such as Claes Oldenburg's Free Stamp in Cleveland, their defenders insisted that they could not be moved because they were "site specific," that is, designed with a very particular place in view. To change their venue would be tantamount to destroying them. This, too, was not a new issue. Greenough had been commissioned to create his work specifically for the Capitol Rotunda. It got moved outside at the sculptor's own request, though swiftly to his profound regret; and it was resituated once again more than half a century after his death. Relocation alone, however, had not denigrated it. Dissensus already had. The country simply could not agree on the most suitable aesthetic for honoring its foremost citizen with a prominently placed statue (fig. 8).

From the Hardcover edition.

Monuments, Memorials, and Americanism

Although the particulars have now grown hazy, older portions of the American public recall that the genesis of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in 1980–83 prompted considerable controversy. It seemed quite shocking at the time that the design competition could be won by a twenty-one-year-old architecture student. Even more provocative, because her plan seemed so austerely postmodern, it failed to fulfill customary notions of what a suitably heroic memorial should look like. Hence the harsh criticism that a "black gash of shame" actually dishonored those who had died in Southeast Asia (fig. 4). A mere list of names placed in a wide-angle pit, with a plaque referring only to an "era" rather than an actual war? Could the nation do no better?

Although H. Ross Perot had initially funded the design competition, he joined traditionalists in denouncing Maya Lin's winning entry and calling for a representational monument showing U.S. soldiers and an American flag. Secretary of the Interior James Watt, who had the power to veto the whole project, allowed it to go forward, but only on condition that a compensatory statue be commissioned and situated nearby (fig. 5). Watt forced his compromise on the federal Fine Arts Commission, which genuinely did not want to upstage Lin's design with what commission chairman and National Gallery of Art director J. Carter Brown called a "piece of schlock."

By 1983 the interchange between Maya Lin and Frederick Hart, the sculptor for the figural addition, served only to intensify ill-feelings underlying two conflicting visions of what might be the most appropriate ways to memorialize a massive number of deaths in an unpopular war. When asked her opinion of Hart's work, Lin candidly replied: "Three men standing there before the world-it's trite, it's a generalization, a simplification. Hart gives you an image-he's illustrating a book." Hart became even harsher when asked whether "realism" was the only way to reach the disaffected veterans and politicians.

The statue is just an awkward solution we came up with to save Lin's design. I think this whole thing is an art war. . . . The collision is all about the fact that Maya Lin's design is elitist and mine is populist. People say you can bring what you want to Lin's memorial. But I call that brown bag esthetics. I mean you better bring something, because there ain't nothing being served.

In the decades since those two interviews took place, Americans have voted with their feet, but more powerfully with their hearts and minds. Lin is a winner.

In 1987 Congress finally began its initial and pedestrian reaction to long-standing requests for a World War II memorial situated in a suitable place of honor in Washington, D.C. By the mid-1990s likely designs received a critical response for several reasons: first, they seemed too grandiose and therefore reminiscent of conservative monuments in Europe; second, they would likely obstruct the widely cherished two-mile vista between the U.S. Capitol and the Lincoln Memorial; and third, they would bisect the Mall by straddling its entire width. There were traditionalists on both sides of the issue: those who wished to preserve the uncluttered "purity" of the Mall and those eager to honor the "greatest generation" with a genuinely worthy plan consistent in merit with others in that coveted location. This conflict boiled up a full head of steam between 1997 and 2000, but Friedrich St. Florian's winning design finally received presidential approval when many pleaded that World War II veterans were rapidly dying and something should be completed before they had disappeared entirely (fig. 6).

Too few Americans are aware that most of the issues raised between 1980 and 2000 had been hashed out long before when initial plans were unveiled for the Washington Monument and the Lincoln and Jefferson memorials. Moreover, major statues meant to honor Washington and Lincoln had also aroused the most intense feelings on similar grounds: sheer size (gigantism), style (classical versus "modern"), location, and even nudity in the case of Horatio Greenough's seated George Washington, commissioned by Congress in 1833, completed in Florence, Italy, in 1839, and placed in the Capitol Rotunda in 1841. Scale, style, site, and apparel (or lack thereof) would become persistent and volatile issues in American art ever after. Monumental is a more neutral euphemism for gigantic and colossal, of course. Many artists, sculptors, and architects who we might find guilty of gigantism were only striving to do monumental work. Suitable scale seems to lie in the eye of the beholder yet also reveals the ambitious needs of a principal stakeholder.

Greenough's Washington touched off one of the earliest conflicts in the United States involving aesthetic criteria, and one of the most representative. A particularly problematic question involved style: how should the Father of His Country be depicted, as an idealized deity or as a revered native statesman? Classical or "American"? Godlike and spiritual or secular yet like-no-other? Greenough's solution turned out to be a hybrid: the head based upon Houdon's life mask certainly resembled Washington, but the body evoked Jupiter and Roman statuary (fig. 7). Hence the work got nicknamed George Jupiter Washington when it wasn't given more insulting designations. Greenough's inspiration was actually the Elean Zeus by Phidias, one of the greatest Greek sculptors, a work known only by description. Greenough was apparently seeking purity and simplicity rather than the pomposity that so many critics seemed to see in the statue. The snarls that ensued would demonstrate that compromise leaves almost no one satisfied.

Greenough's statue as well as Robert Mills's Washington Monument emerged in the wake of failed attempts to commemorate the centennial of the founder's birth by unearthing his body from Mount Vernon for reburial in the Capitol crypt in 1832. The cult of Washington as a superheroic if not immortal figure remained exceedingly strong, though strife persisted over the relative merits of his role as a symbol of national unity and his symptomatic value to southerners as a Virginia-based protochampion of states' rights. The Nullification Crisis early in the 1830s, prompted by South Carolina's threatened secession over tariff issues, added sectionalism to the mix of aesthetic differences and complicated them. Similarly it has long been forgotten that several significant sources of friction in the decade following 1911 involving the Lincoln Memorial arose from sectional tensions left unresolved by the Civil War. That monument, which is virtually devoid of references to slavery and the conflict it generated, was meant to serve as an emblem of national unification. The intertwined boughs of southern pine and northern laurel that gracefully encircle the frieze provide just one indication of that quest. (Because laurel is a symbol of victory, of course, the northern Republicans who called the shots enjoyed a not-so-subtle triumph.)

Serious debate would persist for more than a century following the 1820s: namely, whether monuments and architecture in the United States should pursue styles that feel native and new or should appropriate motifs from antique Greece and Rome. Horatio Greenough received interesting and revealing advice as he embarked upon his impassioned career as the premier American sculptor in the early republic. When he first attempted to model a figure of George Washington, he received wise counsel from a patron, the novelist James Fenimore Cooper: "Aim rather at the natural than the classical." That same heated issue would stay situated at the core of a decade-long quarrel over the most suitable design for the Lincoln Memorial. "Natural" meant more than avoiding stylistic imitation of the ancient world. It also meant having a heroic figure clothed in modern dress, and standing rather than seated like some emperor, Roman or Napoleonic.

Greenough got mixed signals, however, because his fellow New Englander Edward Everett advised him to "go to the utmost limit of size. . . . I want a colossal figure." That muscular word colossal and its synonyms would recur over and over again in intensely heated discussions about the Washington Monument, the Lincoln and Jefferson memorials, and the memorial for Franklin Delano Roosevelt finally unveiled in 1997. Midwestern opponents of the Lincoln Memorial design that ultimately prevailed (albeit scaled back in size owing to considerations of cost and weight) pleaded instead for a "colossal statue" of the man who saved the Union. But in 1969 William Walton, chairman of the Fine Arts Commission, epitomized more than a century of polemics when he wrote to the chairman of the FDR Memorial Commission, a member of Congress: "I urge that we get away from bigness as a manner of memorializing great men. A man's place in history is never determined by the size of his monument."

When Fenimore Cooper discovered the dimensions that Greenough had in mind, he considered them grandiose and advised his friend accordingly. The sculptor stuck with Everett's wishes, however, which reinforced his own aspiration, and designed a massive marble chair from which his seated Washington figuratively contemplated the ship of state he had brought into being. His gestures followed a classical formula seemingly well suited to a brand-new republic. Whereas Washington's right hand points heavenward, the source of law by which men live, the left hand returns his sword to the people because he has completed his service to them. It was not such a bad compromise, actually, between imperatives ancient and modern.

Skeptics scoffed that the oversize statue would not even be able to enter the Capitol for placement in the Rotunda. They were wrong, and initial responses to the monumental piece in 1841–42 seemed more favorable than not, though critics certainly made themselves known. When Greenough arrived from Florence in 1842 and saw how dim the Rotunda lighting was, however, he tried to have torches illuminate his work; but they only made matters worse. Flickering lights in a dim chamber do not enhance greatness. He then pleaded with Congress to move the monument out of doors so that it could be bathed in natural sunlight—a serious error, as it turned out—and that is when the harshest condemnations began to be heard. Maximum visibility only encouraged calumny.

Fierce blasts came from Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, who had offered stiffer warnings than Cooper's concerning size as well as nudity, and from Philip Hone, the former mayor of New York, who recorded the following in his diary:

It looks like a great herculean Warrier—like Venus of the bath, a grand Martial Magog—undraped, with a huge napkin lying on his lap and covering his lower extremities and he is preparing to perform his ablutions in the act of consigning his sword to the care of the attendant. . . . Washington was too prudent, and careful of his health, to expose himself thus in a climate so uncertain as ours, to say nothing of the indecency of such an exposure on which he was known to be exceedingly fastidious.

Nathaniel Hawthorne was pithier: "Did anyone ever see Washington naked? It is inconceivable. He had no nakedness, but I imagine was born with his clothes on and his hair powdered, and made a stately bow on his first appearance in the world." Being unclothed from the waist up was nude enough for the 1840s but particularly so for the Father of His Country, a man renowned for his dignified reserve as well as other self-possessed qualities. On this matter also, however, consensus could not be achieved. Ralph Waldo Emerson described the work as "simple & grand, nobly draped below & nobler nude above." He declared that it "greatly contents me. I was afraid it would be feeble but it is not." In many different ways and for numerous reasons, nudity would become a prime cause of controversy during the century and a half that followed.

Once it was determined that Washington would sit out of doors, exposed to extremes of weather and the uncontrollable excretions of birds, the figure became a prime target for pranksters. One inserted "a large 'plantation' cigar between the lips of pater patriae, while another had amused himself with writing some stanzas of poetry, in a style rather more popular than elegant, upon a prominent part of the body of the infant Hercules." Exactly which body part is unclear; but quite obviously political graffiti did not originate the day before yesterday. This monumental statue increasingly became an occasion for mockery, and Greenough's poignant letter to Robert Winthrop in 1847 sums up his frustration at having his motives and skills misunderstood by a nation so lacking in artistic sophistication.

A colossal statue of a man whose career makes an epoch in the world's history is an immense undertaking. To fail in it is only to prove that one is not as great in art as the hero himself was in life. Had my work shown a presumptuous opinion that I had an easy task before me—had it betrayed a yearning rather after the wages of art than the honest fame of it, I should have deserved the bitterest things that have been said of it and of me. But containing as it certainly must internal proof of being the utmost effort of my mind at the time it was wrought, its failure fell not on me but on those who called me to the task.

Washington's state of undress also made him appear pagan—not exactly proper in a society where evangelical Christianity enjoyed wide appeal. Although Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and many others praised it, the statue continued to inspire wags and scoffers throughout the remainder of the nineteenth century. The early rumor that it was too large to pass through the door of the Capitol gradually became a popular legend. Stories were repeated that it had to be moved outside because it threatened the very foundation of that big building and even that it sank the first ship that attempted to load it for "home" in Leghorn, Italy. The ultimate insult occurred in 1908 when Congress ordered that it be moved to the Smithsonian Institution's "Castle," ironic in turn because of Greenough's disdain for the Gothic style. A monumental mismatch of art and architecture.

During the later twentieth century, when certain works of public sculpture became crazily controversial, such as Claes Oldenburg's Free Stamp in Cleveland, their defenders insisted that they could not be moved because they were "site specific," that is, designed with a very particular place in view. To change their venue would be tantamount to destroying them. This, too, was not a new issue. Greenough had been commissioned to create his work specifically for the Capitol Rotunda. It got moved outside at the sculptor's own request, though swiftly to his profound regret; and it was resituated once again more than half a century after his death. Relocation alone, however, had not denigrated it. Dissensus already had. The country simply could not agree on the most suitable aesthetic for honoring its foremost citizen with a prominently placed statue (fig. 8).

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

"Deep, richly detailed, and enlightening."—The Boston Globe“Compelling. . . . A nuanced study . . . offers an important context for looking at ongoing issues of censorship and debates about the point of art.”—The Miami Herald "Kammen . . . handles these variegated brouhahas with welcome deftness; he squeezes in all the facts while maintaining a nice narrative flow."—The Nation"A detailed and comprehensive survey of the history of artistic battles in the United States."—The Houston Chronicle